20 |

Documentary |

||

The documentary sequence has very different criteria for success than those of the dramatic sequence. Both must follow certain rules of editing to communicate with the audience, but beyond simple continuity, the differences far outweigh the similarities. As Karel Reisz suggested, “A story-film—and this will serve as a working distinction between documentary and story-films—is concerned with the development of a plot; the documentary is concerned with the exposition of a theme. It is out of this fundamental difference of aims that the different production methods arise.”1

The production of the dramatic film is usually much more controlled than that of the documentary. The story is broken down into deliberate shots that articulate part of the plot. Performance, camera placement, camera movement, light, color, setting, and juxtaposition of people within the shot all help advance the plot. The editor pieces together the shots, orders them, and paces them to tell the story in the most effective way.

The documentary generally proceeds in the opposite manner. There are no performers, just subjects that the filmmaker follows. Camera positioning tends to be a matter of convenience rather than intention, and lighting is designed to be as inobstrusive as possible. Documentary filmmakers tend to adhere to their definition of a documentary: a film of real people in real situations doing what they usually do. Consequently, the role of the director is less that of the orchestra conductor than that of the soloist. He tries to capture the essence of the film by working with others—the cinematographer, the sound recordist, and the editor. The documentary film is found and shaped in the editing.2

There are exceptions. Some documentaries are staged—Robert Flaherty's Man of Aran (1934), for example—and some dramatic films proceed in an extemporaneous fashion—John Cassavetes's Faces (1968), for example. Whether the staging of Flaherty's work made it less reliant on the editor is questionable.3 These crossovers have become increasingly notable with the docudrama work of Peter Watkins, Ken Loach, and Don Owen. The editor played an important part in those films.

In the documentary sequence, then, the editor has a crucial and creative function. Given the goals of the documentary, that function gives the editor more freedom than the editing of a dramatic film. With freedom comes responsibility, however.

QUESTIONS OF ETHICS, POLITICS, AND AESTHETICS

QUESTIONS OF ETHICS, POLITICS, AND AESTHETICS

Documentary filmmakers go out and film events that affect the lives of particular people. They film in the place that the event occurs with the people who are involved. They then edit the film. Questions immediately arise. Would the truest representation of the facts be obtained by simply stringing all of the footage together, or is some shaping necessary?

As soon as the shaping process begins, ethical questions arise. Is the event honestly presented? Does it accurately reflect the perceptions of the participants? How much ordering of the footage is necessary to make the event interesting to an audience? Do the filmmaker and editor betray the event and the participants when they impose dramatic time on the footage?

The editing of documentary footage often leads to a distortion of the event. The filmmaker's editorial purpose often supersedes the raw material. From Leni Riefenstahi in Triumph of the Will (1935) to Michael Moore in Roger and Me (1989), filmmakers have edited documentaries to present their particular vision. For them, the ethical issue is superseded by the need to present a particular point of view.

The documentary is sometimes referred to as a sponsored film. Whether it is a public affairs documentary or a documentary underwritten by a local church, the sponsor has a particular goal. That goal may be journalistic, humanistic, or mercenary, but it always has on impact on the film that the director and editor make.

Unlike the dramatic film, the goals of the documentary are not entertainment and, ultimately, economic success. Nevertheless, those goals must be met, or the sponsor may claim the footage from the director, just as Sinclair Lewis took Eisenstein's Mexican footage. This is one of the reasons why some filmmakers finance their own documentaries. Financial independence may mean low-budget filmmaking, but it also gives rise to a personal filmmaking style that only independence can provide. Most documentary films are sponsored, however, and the sponsor usually has an impact on the type of film that is created.

One of the most interesting dimensions of the documentary is the aesthetic freedom that is available even within the ethical and political bounds. Filmmakers are basically free to experiment with any mixture of sound and visuals that captures an insight they find useful. Their choices may be incidental to the overall shape of the film. When Leni Riefenstahl decided that the beauty of the human form was more important than the Olympic competition and its outcome in Olympia (1938), she made an aesthetic decision that influenced both the shape of the overall film and the content of the individual sequences.

When Humphrey Jennings decided to use music as the predominant sound in his wartime propaganda film Listen to Britain (1942), he opted to omit the interviews and footage of political leaders and instead selected a freer presentation of the images and the message of the film. This aesthetic choice influenced everything else in the film.

The range of aesthetic choices in the documentary is far wider than is available in the dramatic film. Consequently, in the documentary, the editor can stretch his or her editing experience. It is in this type of film that creative editing is most encouraged and learned.

ANALYSIS OF DOCUMENTARY SEQUENCES—MEMORANDUM (1966)

ANALYSIS OF DOCUMENTARY SEQUENCES—MEMORANDUM (1966)

This chapter uses a single film, Memorandum (1966), to examine the documentary. Memorandum was produced at the National Film Board of Canada. Donald Brittain and John Spotton directed it, and Spotton also photographed and edited the film. The documentary examines the Holocaust from a retrospective point of view. The film centers around the visit of a concentration camp survivor, Bernard Lauffer, to Bergen-Belsen, the camp from which he had been liberated 20 years earlier. In April 1965, Lauffer traveled to Germany with his son and other survivors.

The filmmakers built on his visit to present modern Germany at a time when Israel was opening its embassy for the first time and war criminals from Auschwitz were on trial. Interviews with Germans who served in the war intermingle with newsreel footage of Hitler and the concentration camps. Old and new footage are unified by the narrator. Always, the question is asked: How could the Holocaust happen in a land as cultured as Germany? The role of the doctors and the churches is also explored.

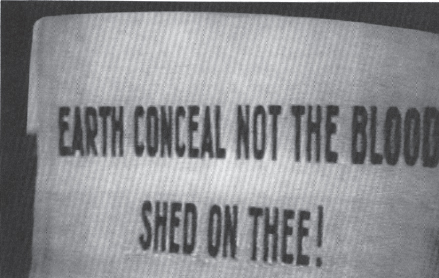

In a film of less than an hour, the filmmakers presented an examination of the Holocaust. They used the film to remind the audience that once such an event enters the public consciousness, it becomes part of that consciousness. The film warns that those who were responsible for the Holocaust were ordinary men who loved their wives and children, men who killed by memorandum rather than pull the trigger themselves.

The commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the liberation of Bergen-Belsen ties the film together. Memorandum does not pretend to be a cinema virité treatment of the life of a concentration camp survivor. That would be another film.

SIMPLE CONTINUITY AND THE INFLUENCE OF THE NARRATOR

In the prologue to Memorandum, we watch a waitress washing beer mugs and preparing service for the beer garden. We see close-ups of what she is doing, and then a series of shots follows her as she goes-about her duties. This simple continuity presents a young woman performing one aspect of her job. The size of the beer mugs and her uniform tell us that the setting is Germany (Figure 20.1).

On the sound track, the narrator introduces the place and time: Munich, summer of 1965. The young woman is Fräulein Bellich. The narrator says, “She was born in 1941, the year Hitler decided she should never see a Jew. But that's finished now.”

Without the narration, the footage of Bellich might have opened a film about Munich, beer gardens, or German youth. However, when the narrator Donald Brittain mentions Hitler, he adds direction to the visuals. When Brittain says of the Holocaust, “But that's finished now,” he adds irony to the narration because the film is dedicated to the proposition that it isn't finished. As this sequence shows, even simple visual continuity can be directed and shaped by sound.

A sequence that follows the prologue illustrates how simple continuity can be supported by the narration. The sequence, which features a Jewish funeral in Hanover, begins with a shot of the Hebrew markings on gravestones in the Jewish cemetery. This provides visual continuity with the prior scene, which ended on the Hebrew lettering of the Israeli embassy sign in Cologne. All of the participants of the funeral seem to be elderly. The shots detail the funeral procession, which is led by a rabbi. We see the German police on guard, and we seen the mourners, primarily the widow. The sequence ends with the widow grieving, dropping a shovelful of dirt on the lowered casket.

The visuals are primarily close-ups except for the long shot of the procession as it nears the grave site. The close-ups give the sequence an intensity that underscores the feelings of the participants of the funeral. The narrator introduces the funeral and speaks about the right to hold a Jewish funeral in modern Germany, a right that was denied to all who died in the concentration camps. He also talks about the number of people who died. The German Jewish community of 500,000 before the war became a community of 30,000 in 1965, and most of the survivors are elderly. With a tone of irony, the narrator implies that it is a special privilege for a Jew to be buried in Germany.

Figure 20.1 |

Memorandum, 1966. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada. |

These two sequences illustrate how the narration can support the visual or direct it to another meaning. They also illustrate the importance of sound in the documentary.

THE TRANSITIONAL SEQUENCE

To move from the present into the past, Spotton and Brittain adopted a gradual approach that embraces new footage and slowly moves into archival footage. The narration plays a key role in identifying the time period, but in this sequence, the visuals play a stronger role. One sequence begins with close-ups of the telephone operators of a German hotel. The camera passes through the doors of a fancy hotel where elegance and propriety are clearly elements of modern German life. The narrator introduces Lauffer, who is dining with his colleagues in the hotel. The narrator describes how Lauffer was unwelcome in Germany 24 years earlier and how his treatment and the treatment of other Jews “has drained the German landscape of its humanity.” This sound cue leads to a German announcement from the war that Communists, partisans, and Jews are to be arrested and confined in concentration camps.

We see a radio, a military cap, and symbols of the authority that the Germans exercised over the Jews. The film then cuts to visuals of artifacts and monuments to the victims of the Holocaust: a towering statue in Austria, a torture instrument in Warsaw. The narrator tells us that torture was too dignified a fate for the Jews and that there were other places than torture chambers for the Jews.

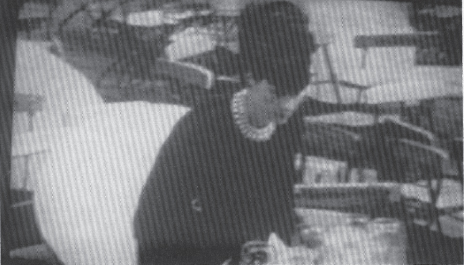

The next scene is of the museum at Dachau, where visitors walk past enlarged pictures of the inmates. Visuals of medical experiments are explained by the narrator. Shots of the museum visitors are interspersed with images of “medical experiments.” Images of an experiment where the human subject dies conclude this scene. The narrator's explanation underscores the inhumanity of the closely shot images (Figure 20.2).

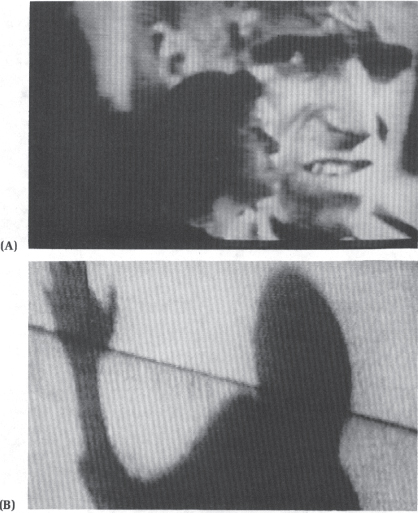

From the still image of death, Brittain and Spotton cut to the moving image of Hitler opening the Dachau camp in 1933. The footage was shot on a large scale and seems rather operatic. The narrator takes us from the opening of the camp to a newsreel celebrating Hitler's accomplishments, particularly the opening of the autobahn in 1936 (Figure 20.3).

This scene is followed by archival shots of the large-scale destruction of Jewish property in 1938: Krystallnacht. This event is downplayed by Joseph Goebbels in archival footage. The visuals are calm and rather benign, but the narration is ominous. Brittain describes Hitler's comment that war will bring the annihilation of Europe's Jews and discusses how this remark was interpreted as a figure of speech. The final shot is of a crowd cheering Hitler. The next sequence begins with a shot of a modern crowd.

Figure 20.2A and B |

Memorandum, 1966. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada. |

Memorandum, 1966. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada. |

The narrator takes the lead in this sequence to move us between periods: from Lauffer to the artifacts of the camps, from the artifacts to the modern tour of Dachau, from Dachau to the newsreel footage of Germany in the 1930s. Within each scene is a visual variety that punctuates a world of contrasts. The first contrast is of modern, affluent Jews and older, apprehensive concentration camp survivors; the second is of the symbols of torture in the past and of the victims. The third contrast is of the museum, where healthy visitors look at photographs of the most grotesque medical experiments ever undertaken on humans, and the final contrast is the footage of Hitler and Germany in the 1930s and the progress of modern Germany. The narration provides the contrast between what we see and what we know will happen.

Figure 20.3C |

Memorandum, 1966. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada. |

Throughout this sequence, the issue of conflict and contrast in each scene carries us toward the fuller introduction of the past. This sequence visually introduces the history of the Holocaust, and it marks the beginning of the shift toward a greater emphasis on the past than on the present. The narrator is important in this sequence, but not as important as the visuals in preparing the transition to the past.

THE ARCHIVAL SEQUENCE

When archival footage is used, the narrator becomes critical. In the sequence where the narrator begins to tell us Lauffer's story, the film focuses on Lauffer's hands and the documents he holds. The narrator tells about the Germans’ offer to sell Lauffer's brother's ashes to the family for 24 marks. The Warsaw ghetto was the first of 11 places where Lauffer was confined during the war. The film cuts to archival footage of a close-up of a Jew holding his documents. The cut from an image of documents in 1965 to a similar image of documents in 1942 provides a visual continuity for the transition into the past.

The narrator and Lauffer both speak of life in the ghetto. We see a Jewish committee meeting with German officials as Lauffer describes that the committee was composed of good people. The narrator suggests that centuries of oppression have trained the Jews to wait for a bad situation to improve. The narrator editorializes about the deterioration of life in the ghetto and how it was the children who suffered the most. The images support the narration. When Brittain speaks of dehumanization in the ghetto, the footage illustrates that dehumanization.

Archival footage shows Hitler at Berchtesgaden greeting a young child. Over this footage, the narrator tells us that Hitler decided in 1941 that all of the Jews of Europe were to be systematically exterminated. He details Lauffer's losses: his four brothers, four sisters, and parents were killed. In this sequence, the juxtaposition of the visuals and their tranquility contrast with the narration. The sequence ends with visuals of children playing. The narrator tells us that they were photographed for propaganda purposes and then led into the gas chambers. The narration thus goes beyond the visuals to rectify misinformation that the visuals present (Figure 20.4).

The archival sequence is presented carefully. It begins with a direct correlation between visuals and narration and gradually begins to use the images as a counterpoint to the narration. The film returns to an almost direct correlation between narration and visuals as the sequence ends. The sound track is thus the critical shaping device in this archival sequence.

Figure 20.4 |

Memorandum, 1966. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada. |

A SEQUENCE WITH LITTLE NARRATION

One sequence in Memorandum documents a visit to Auschwitz. Lauffer had grown up 9 miles from Auschwitz, he had helped build it, and his parents had died there. This narration serves as the transition into the visual sequence at Auschwitz. The narrator's few comments primarily prepare the audience for the sequences to come; he mentions two of the featured topics: Papa Kadusz's chapel and Wilhelm Bolge's cruelty to inmates. Both men went on trial in Hamburg. The trial itself is featured in a later sequence. The narrator also explains about the location where Rudolf Hess was hanged by the Poles; he speaks about Hess as a family man. This commentary takes us into the next sequence, which is archival and concentrates on Heinrich Himmier's paternal attitude toward the S.S. men who carried out the killings of Jews. The narration leads to an articulation of the methodology of death. The principal goal of the narration in the Auschwitz sequence is to provide a transition or foreshadowing for later sequences (Figures 20.5 and 20.6).

The visuals in the Auschwitz sequence, which is organized as a tour of the camp, are presented very differently than in every other sequence. The sequence follows visitors and their Polish guides through the different areas of the camp to see the locations where Jews entered the camp and where they were killed. Because they were filmed primarily as long shots, the human images seem distant and dispassionate. There is little camera mobility compared to earlier sections, and as a result, the sequence proceeds visually at an unhurried pace.

Figure 20.5 |

Figure 20.6 |

Memorandum, 1966. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada. |

When children's artifacts are shown, the shot is a slow, handheld shot that lingers. The camera moves to animate the statue of a child, but for the most part, movement follows action. Natural sound allows us to listen to the guides explain about the concentration camp. It is only when the narrator speaks of the torture that Bolge inflicted on the Jews in the camp that we see the first close-ups of the visitors. Two or three shots of the faces of the visitors are the closest that Brittain and Spotton come to using any visual intensity in the sequence. These shots stand out in contrast to the predominance of long shots in the sequence.

The Auschwitz sequence was designed to be as similar to cinema verité as possible. It is one of the most journalisticlike sequences in the film.

THE REPORTAGE SEQUENCE

Toward the end of Memorandum, the sequence about Lauffer's visit to Bergen-Belsen is presented as straight reporting (Figures 20.7 to 20.12). The narrator relinquishes his editorial role and simply introduces people and places. Although he fills in the details of Lauffer's survival in Bergen-Belsen before liberation, the narrator's role is principally to support the visuals and synchronous sound of the participants as they speak or are interviewed.

The sequence begins with a cocktail party held the night before the visit. The organizers and participants greet one another, and we are introduced to Brigadier Glynn Hughes, who led the British forces that liberated Bergen-Belsen in April 1945. We are also introduced to two former inmates, Clare Silvernick and Joseph Rosenzafft, who led the inmates who were liberated from the concentration camp. The interaction among the participants is warm and friendly, and the scene ends with Rosenzafft's resolve to survive.

Figure 20.7 |

Memorandum, 1966. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada. |

Figure 20.8 |

Figure 20.9 |

Memorandum, 1966. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada. |

Figure 20.10 |

Figure 20.11 |

Memorandum, 1966. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada. |

Figure 20.12 |

Memorandum, 1966. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada. |

The film cuts to Bergen-Belsen on the day of liberation. The archival footage used here is the most difficult in the film to watch. At the time of liberation, death and disease were omnipresent. The narrator tells us that Lauffer weighed 70 pounds, and Lauffer himself tells about receiving a cigarette from one of the liberators, taking two puffs, and collapsing. The archival footage continues with the British liberators and Kramer, the camp commandant, who was captured. In this scene Lauffer seems to enter a dialogue with the narrator about Josef Kramer's execution and how easy a death Kramer experienced compared to the deaths of the camp's inmates. The sequence ends with the delousing of inmates who are so emaciated that it's difficult to believe that they will survive.

The next scene is of the town of Belsen in 1965. The visuals show its citizens pouring out of a church after Sunday Mass. The majority appear to be older people. The narrator talks of their not knowing of the camp during the Holocaust, although there was too much evidence toward the end of the war to deny. Brittain also editorializes about the appeal of Nazism in this rural region.

On the bus ride to Belsen, Lauffer speaks of his views about Germany, how it appears, and how he feels. The rain continues as the group leaves the buses.

On the site, Brigadier Hughes is interviewed about the day of liberation. He is jovial and jokes about still having Commandant Kramer's desk. The interviewer asks him whether this makes him feel strange. Hughes replies, “Not at all. It's a very good, heavy desk.” Lauffer and Silvernick watch with pained expressions.

In the next scene, Lauffer and his son visit the grave of an uncle who died 3 days after liberation. A young Christian penance group is introduced. The members are helping to build an information center at Belsen. They are disillusioned with the values of their parents. They are young, and yet they seem to be tentative about being photographed at the Bergen-Belsen camp.

The site visit officially begins. The survivors walk past mounds of buried dead. In one of these mounds, Anne Frank is buried, the narrator tells us. Handheld shots follow Lauffer and his son. The survivors take on a somber tone as they approach the monument to the dead. The group approaches the site, lays down a wreath, and says a prayer for the dead. The camera films the scene as a long shot, and a series of close shots includes Hughes and Rosenzafft. A moving shot catches the survivors consoling one another.

The synchronized sound scene gives way to another. A frustrated Lauffer speaks of the mounds of buried dead as the group walks back to the bus. He can't find the proper words, but his son helps him. “Here lie five hundred,” he says. “Next year, it will be four hundred. They want to minimize what happened here.” Lauffer suggests that the Germans should not have beautified the site; they should have left it as they found it in 1945. The film cuts to the hotel in Hanover, and the sequence is over.

Perhaps more than any other part of the film, this sequence featuring the commemorative visit to Bergen-Belsen proceeds as straight reporting of the events. The archival footage of the camp at the time of liberation and the shots of the town in 1965 flesh out the sequence, providing context for the visit. In a sense, the entire film leads up to this sequence. In it, Brittain and Spotton let the footage speak for itself. There is a minimum of editorializing in the narration and minimal use of the kind of juxtaposition of sound and picture used extensively earlier in the film.

This sequence, however, does conform thematically with the other sequences described in this chapter. They all examine the Holocaust from two perspectives—past and present—and they all remind the viewers of the character of the Holocaust as well as of the deep feeling of its survivors, like Bernard Lauffer, and their commitment not to forget.