19 |

Comedy |

||

When examining the editing of a comedy sequence, it is critical to distinguish the role of the editor from the roles of the writer and the director. The burden of creative responsibility for the success of verbal humor, whether a joke, a punch line, or an extended witty repartee, lies with the writer for the comic inventiveness of the lines and the director and actor for eliciting the comic potential from those lines. The editor may cut to a close shot for the punch line, but the editor's role in verbal humor is somewhat limited.

With regard to visual humor, the editor certainly has more scope.1 Indeed, together with the writer, director, and actors, the editor plays a critical role.

It is important to understand that humor is a broad term. Unless we look at the various types of comedy, we may fall into the trap of overgeneralization.

CHARACTER COMEDY

CHARACTER COMEDY

Character comedy is the type of comedy associated with Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, and Langdon in the silent period, and with the Marx Brothers, W. C. Fields, Mae West, Martin and Lewis, Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, and Woody Allen in the sound period. Abroad, these ranks are joined by the great comedians Jacques Tati, Pierre Etaix, Peter Sellers, and John Cleese.

The roles of these character comics were associated with the particular personae that they cultivated, which often did not change throughout their career. A character role is somewhat different from a great comic performance by a dramatic performer—for example, Michael Caine in Alfie (1966)—in the sense that this screen persona provides a different relationship with the audience. It allows Woody Allen to address and to confess to the screen audience in Annie Hall (1977); it allows Chaplin's Tramp to be abused by a lunch machine in Modern Times (1936); it allows Groucho Marx to indulge in non sequiturs and puns that have nothing to do with the screen story in Duck Soup (1934). The audience has certain expectations from a comic character, and it is the job of the editor to make sure that the audience isn't disappointed.

SITUATION COMEDY

SITUATION COMEDY

The most common (on television and in film) is the situation comedy. This type of comedy tends to be realistic and depends on the characters. As a result, it is generally verbal with a minimum of pratfalls. The editing centers on timing to accentuate performance; the editor's role with situation comedy is more limited than with other types of comedy sequences.

SATIRE

SATIRE

A third category of comedy is satire. Here, because anything goes, the scope of the editor is considerable. Whether we refer to the dynamic opening of Paddy Chayefsky's The Hospital (1971) or Terry Southern and Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strongelove (1964), which ranged from absurdist fantasy to cinema verité, the range for the editor of satirical sequences is challenging and creative.

FARCE

FARCE

The editor is also very important in farce, such as Blake Edwards's The Pink Panther (1964), and in parody, such as Sergio Leone's The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1967). In The Pink Panther, for example, the quick cut to Robert Wagner sneaking out of Inspector Clouseau's bedroom, having hidden in the shower, is instructive. Earlier, Clouseau had turned on the shower without noticing its occupant. When the wet Wagner sneaks from the room, his ski sweater, which, of course, is now wet, has stretched to his toes. Logically, such an outcome is impossible, but in farce, such absurdity is expected.

EDITING CONCERNS

EDITING CONCERNS

Beyond understanding the characteristics of the genre he is working with, the editor must focus on the target of the humor. Is it aimed by a character at him- or herself, or does the humor occur at the expense of another? Screen comedy has a long tradition of comic characters who are the target of the humor. Beyond these performers, the target of the humor must be highlighted by the editor.

If the target is the comic performer, what aspect of the character is the source of the comedy? It was the broad issue of the character's sexual identity in Howard Hawks's Bringing Up Baby (1938). The scene in which Cary Grant throws a tantrum wearing a woman's housecoat is comic. What the editor had to highlight in the scene was not the character's tantrum, but rather his costume. In Sydney Pollack's Tootsie (1982), the source of the humor is the confusion over the sexual identity of Michael (Dustin Hoffman). We know that he is a man pretending to be a woman, but others assume that he is a woman. The issue of mistaken identity blurs for Michael when he begins to act like a woman rather than a man. Here, the editor had to keep the narrative intention in mind and cut to surprise the audience just as Michael surprises himself.

Comedy comes from surprise, but the degree of comedy comes from the depth of the target of the humor. If the target is as shallow as a humorous name—for example, in Richard Lester's A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966), two characters are named Erronius and Hysterium—the film may elicit a smile of amusement. To develop a more powerful comic response, however, the very nature of the character must be the source of the humor. Jack Benny's vanity in Lubitsch's To Be or Not to Be (1942), Nicolas Cage's sibling rivalry and the anger it engenders in Norman Jewison's Moonstruck (1987), and Tom Hank's immaturity and anger in David Seltzer's Punchline (1989) are all deep and continuous sources of comedy arising from the character.

When comedy occurs at the expense of others, the degree of humor bears a relationship to the degree of cruelty, but only to an extent. If the character dies from slipping on a banana peel, the humor is lost. The degree of humiliation and pain is the variable. Too much or too little will not help the comic situation. This is why so many directors and editors speak about the difficulty of comedy. Many claim that it is the most difficult type of film to direct and to edit.

Examples of this type of humor range from the physical abuse of the Three Stooges by one another to the accidental killing of three little dogs in A Fish Called Wanda (1988). This type of humor can be present in a very extreme fashion, such as in the necessity of Giancarlo Giannini's character in Seven Beauties (1976) to perform sexually with the German camp commandant. Failure will mean death. This painful moment is excruciatingly funny, and the director and editor have wisely focused on the inequity, physical and political, in the relationship of the momentary lovers. The reversal of the conventions of gender roles is continually reinforced by images of her large form and his miniature one. The editing supports this perception of the power relationship and exploits his victimization.

Equally painful and humorous is the situation of the two principal characters in Ethan and Joel Coen's Raising Arizona (1987). The husband and wife are childless, and to solve their dilemma, they become kidnappers and target a millionaire with quintuplets. The abduction of one of the children is a comic scene in which the editor and director reverse the audience's perception of who the victim is. The kidnapper is presented as the victim, and the child is presented as the aggressor. He moves about freely, eluding the kidnapper, and the implication is that his movement will alert his parents.

Whether the source of the comedy is role reversal, mistaken identity, or the struggle of human and machine, the issue of pace is critical. When Albert Brooks begins to sweat as he reads the news in Broadcast News (1987), the only way to communicate the degree of his anxiety is to keep cutting back to how much he is sweating. The logical conclusion is that his clothes will become wringing wet, and of course, this is exactly what happens. Pace alerts us to the build in the comedy sequence. What is interesting about comedy is that the twists and turns require build or else the comedy is lost. Exaggeration plays a role, but it is pace that is critical to the sequence.

Consider the classic scene in Modern Times in which Chaplin's character is being driven mad by the pace of the assembly line. His job is to tighten two bolts. Once he has gone over the edge, he begins chasing anything with two buttons, particularly women. The sequence builds to a fever pitch, reflecting the character's frenzied state.

Pace is so important in comedy that the masterful director of comedy, Frank Capra, used a metronome on the set and paced it faster than normal for the comedy sequences so that his actors would read the dialogue faster than normal.2 He believed that this fast tempo was critical to comedy. Attention to pace within shots is as important to the editing of comic sequences as is pace between shots.

If we were to deconstruct what the editor needs to edit a comedy sequence, we would have to begin with the editor's knowledge. The editor must understand the material: its narrative intention, its sources of humor, whether they be character-based or situation-based, the target of the humor, and whether there is a visual dimension to the humor.

The director should provide the editor with shots that will facilitate the character actor's persona coming to the forefront. If the source of the humor is a punch line, has the director provided any shots that punctuate the punch line? If the joke is visual, has the director provided material that sets up the joke and that executes it? Unlike other types of sequences, a key ingredient of humor is surprise. Is there a reaction shot or a cutaway that will help create that surprise? The scene must build to that surprise. Without the build, the comedy might well be lost.

Another detail is important for the editor: Has the director provided for juxtaposition within shots? The juxtaposition of foreground and background can provide the surprise or contradiction that is so critical to comedy. Blake Edwards is particularly adept at using juxtaposition to set up the comic elements in a scene. The availability of two fields of action, the foreground and background, are the ingredients that help the editor coax out the comic elements in a scene. For example, if the waiter pours the wine in the right foreground part of the frame, the character begins to drink from the wine glass in the middle background of the frame. The character drinks and the waiter continues to pour. This logical and yet absurd situation is presented in Victor/Victoria (1982). Edwards often resorts to this type of visual comedy within a shot. These elements, combined with understanding how to pace the editing for comic effect, are crucial for editing a comedy sequence.

THE COMEDY DIRECTOR

THE COMEDY DIRECTOR

Comedy may be a difficult genre to direct, but there are some directors who have been superlative. Aside from the great character comics who became directors—Chaplin, Keaton, and, in our time, Woody Allen—a relatively small number of directors have been responsible for most of the great screen comedies. Ernst Lubitsch was the best at coaxing more than one meaning from a witty piece of dialogue. His films, including Noel Coward's Design for Living (1933), Samson Raphaelson's Trouble in Paradise (1932), and Billy Wilder's Ninotchka (1939), are a tribute to wit and civility. Howard Hawks, particularly in his Ben Hecht films (His Girl Friday, 1940; Twentieth Century, 1934) and his screwball comedies (Bringing Up Baby, 1938; I Was a Male War Bride, 1949; Monkey Business, 1952), seemed to be able to balance contradictions of character and the visual dimension of his scenes in such a way that there is a comic build in his films that is quite unlike anyone else's. The comedy begins as absurdity and rises to hysteria. He managed to present this comedic build with a nonchalance that made the overt pacing of the sequences unnecessary. His performers simply accelerated their pace as the action evolved.

In his films (Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939; Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936), Frank Capra was capable of relying on lively dialogue and surprising behavior by his characters to generate the energy in his comedy sequences. Capra, however, was more likely than other directors to use jump-cutting within a scene to increase its energy. Preston Sturges was similar to Capra in that he resorted to editing when necessary (The Great McGinty, 1940; Sullivan's Travels, 1941), but he usually relied on language and performance to develop the comedy. He differed from the aforementioned directors in the satiric energy of his comedy. Whether it was heroism (Hail the Conquering Hero, 1944) or rural morality (The Miracle of Morgan's Creek, 1944), Sturges was always satirizing societal values, just as Capra was always advocating them. Satire is always a better source of comedy than advocacy, and consequently, Sturges's films have a savage bite rare among comedy directors.

Billy Wilder was perhaps most willing to resort to editing juxtapositions to generate comedy. That is not to say that his films don't have other qualities. Indeed, Wilder's work ranges from the wit of Lubitsch (The Apartment, 1960) to the absurdism of Hawks (Some Like It Hot, 1959) to the satiric energy of Sturges (Kiss Me, Stupid, 1964). Like Hawks, Wilder also made films in other genres. Consequently, the editing of his films is more elaborate than that of the directors mentioned above.

Contemporary directors who are exceptional at comedy include Blake Edwards (the Pink Panther series) and Woody Allen. Edwards is certainly the more visual of the two. We will look at an example from his body of work later in this chapter. Woody Allen, on the other hand, is interested in performance and language in his films. Consequently, the editing supports the story and highlights the performance of his actors. His work is most reminiscent of Ernst Lubitsch in its sense of economy. Although there are marvelous sequences that rely on editing in The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985) and Radio Days (1987), editing rarely plays a prominent role in the creation of comedy in his films.

Another director that should be mentioned here is Richard Lester (A Hard Day's Night, 1964; Help!, 1965). Of all of the directors mentioned, Lester most relies on editing to achieve juxtaposition and surprise. It would be an exaggeration to say that this makes him the most filmic of the comic directors, but his use of editing does make him particularly interesting.

The aforementioned are the great American directors of comedy. There are exceptional foreign directors as well, particularly the French actor-director Jacques Tati, whose films (Mr. Hulot's Holiday, 1953; Mon Oncle, 1958) are classics of screen pantomime. Also important to mention are some individual directors who are not known for comedy but have directed exceptional film comedies. They range from George Stevens (The More the Merrier, 1943) to Lewis Gilbert (A Fish Called Wanda). Joan Micklin Silver directed the comedy-drama Crossing Delancey (1988), and George Roy Hill directed the broad, outrageous Slap Shot (1977). The best comedy on screen recently has been directed by comedy performers who became directors: Woody Allen, Steve Martin, Rob Reiner, and Danny De Vito. Although there has been good comic writing by James Brooks, John Hughes, and John Patrick Shanley, comedy in the 1980s and 90s has not had the resurgence of the action film. Comedies are being produced, but with the exception of Woody Allen and John Cleese, great screen comedy is still elusive. There are new comic characters—Bill Murray, Robin Williams, Jim Carrey, Mike Myers—but their screen personae have not been as powerful as those of their predecessors.

THE PAST: THE LADY EVE— THE EARLY COMEDY OF ROLE REVERSAL

THE PAST: THE LADY EVE— THE EARLY COMEDY OF ROLE REVERSAL

The Lady Eve (1941), by writer-director Preston Sturges, tells the story of a smart young woman (Barbara Stanwyck) who is a professional gambler. She meets a rich young man (Henry Fonda) aboard an ocean liner. She determines their fate; they fall in love. When he learns that she is a gambler, he breaks off the relationship. Ashore, filled with the desire for revenge, she dons a British accent and visits his home. She convinces him that, because she looks so much like the first woman, she must be someone else. He falls in love with her again. On their honeymoon, she confesses to a string of lovers, and he leaves her. He sues for divorce, but she refuses his settlement. He goes away. They meet again aboard a ship. Believing that she is his first love, he falls for her again. As they confess to one another that they are married, the door closes and the film ends.

Although the film relies strongly on verbal comedy, Sturges also exploited the dissonance between the verbal and the visual. When Pike (Fonda) takes his first meal on the ocean liner, every woman in the dining room tries to capture his attention. In an elaborate sequence, Eve (Stanwyck) watches in her make-up mirror as Pike avoids the attention of various women. She seems dispassionate until the film cuts to a midshot that reveals her indignation at the situation. This is followed by a close-up of her foot, which she has extended to trip Pike. In the next shot, he is flat on his face, having smashed into a waiter bearing someone's meal (Figure 19.1). The contrast between her dispassionate appearance and her behavior provides the surprise from which comedy springs. The indignation he expresses after his fall turns into an apology as she accuses him of breaking the heel of her shoe. He introduces himself, but she dismisses it, saying that everyone knows who he is. The verbal twists and turns in this sequence are typical of the surprise that characterizes the film. The wittiness of the dialogue, the visual pratfalls, the verbal twists, and the superb performances are the major sources of humor in the film.

Aside from the exceptional quality of the script, Sturges's approach to the editing of the film is not unusual. Later in the film, however, there is a sequence that relies totally on the editing to create comedy. Pike is now married to Eve, who is posing as Lady Sedgewicke. They are on their honeymoon. To avenge herself for the first round of their relationship in which he left her because she was a gambler, Eve has decided to confess to a string of lovers. She begins slowly and tells him about eloping with a stable boy at the age of 16. Instead of cutting directly to a shot that reveals Pike's disappointment, Sturges cut to a shot of the train rushing through the night. This first confession is paced slowly, but as the confessions come faster, Sturges cut to the train rushing through a tunnel. The pace of editing quickens between her confession, his response, and the train. It leads us to the aching disillusionment of the new husband.

Figure 19.1 |

The Lady Eve, 1941. Copyright © by Universal City Studios, Inc. Courtesy of MCA Publishing Rights, a Division of MCA Inc. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

The entire sequence concludes with the train stopping and Pike leaving the train and the marriage. After the first story of the elopement with the stable boy, the cutting takes over, illustrating Pike's rising temper and her candor. The motion of the train underscores the emotion of the situation. It also provides a visual dimension beyond the verbal interchange. The rushing train implies the termination of the relationship rather than the consummation of the marriage. The result is comedy.

The approach that Sturges took, with its reliance on verbal humor and the occasional use of visual humor, is typical of the comedy sequences of his time.

THE PRESENT: VICTOR/VICTORIA— A CONTEMPORARY COMEDY OF ROLE REVERSAL

THE PRESENT: VICTOR/VICTORIA— A CONTEMPORARY COMEDY OF ROLE REVERSAL

In 1982, Blake Edwards wrote and directed Victor/Victoria. In the 40 years between The Lady Eve and Victor/Victoria, the balance between the verbal and visual elements of comedy shifted. Today's films have a much greater variety of visual humor.

Victor/Victoria is the story of a young performer, Victoria (Julie Andrews) who is not very successful in 1930s Paris until she meets a gay performer, Toddy (Robert Preston), who suggests that she would improve her career if she pretended to be a man who pretended to be a female performer. She follows his advice, pretends to be a Polish count, and under Toddy's tutelage, she is an instant success. An American nightclub entrepreneur, King Marchand (James Garner), sees her perform and is very taken by her performance and by her female stage persona until he discovers that she is “Victor.” He doesn't believe that she is a man and tries to prove that she really is a woman.

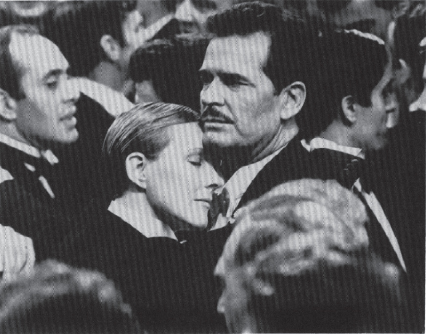

This story about mistaken identity and sexual attitudes has a happy conclusion. The humor, both verbal and visual, usually generates from the confusion about sexuality. For example, one of the best visual jokes in the film is a close-up of King and “Victor” dancing cheek-to-cheek (Figure 19.2). They are clearly romantically involved with one another. In a preceding scene, she had acknowledged that she is a woman, and they initiated their relationship. The dancing shot begins in a close-up of the two lovers, and when the camera pulls back, we see that they are dancing cheek-to-cheek in a gay bar. All of the other loving couples are male.

Figure 19.2 |

Victor/Victoria, 1982. © 1982 Turner Entertainment Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

A more typical comedy sequence occurs early in the film. Victoria and Toddy are eating a meal that they can't afford in a French café. The sequence illustrates their hunger and the instrument of their escape: a cockroach that Victoria intends to put onto her salad. She tries to dump the cockroach from her purse onto the salad, but a close-up shows that she has failed. When the suspicious waiter asks her how her salad is, she is jumpy. Toddy asks for another bottle of wine to distract the waiter, who notices they haven't finished the first bottle yet. In a close-up, the cockroach moves from the purse to the salad. Victoria sees the cockroach and screams. The suspicious waiter collides with another waiter, and the cockroach is flung onto another table. Attracted by the commotion, the manager comes to the table. In midshot, he attempts to calm the situation, but he, too, is suspicious. The following shots of Toddy defending Victoria and of the manager handling the accusation create the sense that either Toddy or Victoria will be held responsible for the bill. Just as the situation seems to be lost, the film cuts to a close-up of the cockroach on a patron's leg. The dialogue of Toddy and the manager continues on the sound track, but the visuals shift to the cockroach. The film cuts to a close-up of the patron as she screams and then quickly cuts to an exterior shot of the restaurant, where we see the growing pandemonium from afar.

The twists and turns of this sequence provide the context for the humor. The waiter's behavior and the cockroach constitute the surprises that give rise to the comedy. Edwards clearly understood the role of conflict and contrast in the creation of comedy. The editing follows the development of the conflict and at strategic points introduces the necessary elements of surprise. The comedy in this sequence is primarily visual, although there is some verbal humor, particularly from the waiter.

Edwards's use of visual humor to by-pass the obligatory but uninteresting parts of the narrative demonstrates how useful the comedy sequence can be. The obligatory part of the narrative is the introduction of “Victor” to a music impressario who can help her career. Toddy takes her to the impresario's office where the secretary tells them that her boss is unavailable. The scene has been played many times before: The characters lie to or charm the secretary, the would-be performer wows the impresario, and a career is launched. To avoid this trite approach, Edwards introduced a new element. While Toddy and “Victor” wait to see the great man, another would-be star enters: a tuxedo-clad gentleman with a bottle of champagne who claims to be the greatest acrobat in the world. The secretary refuses him entry as well.

The man opens the bottle of champagne, offers the secretary a glass, and proceeds to do a handstand, cane placed in the champagne bottle, his other hand on the secretary's head. This distraction has allowed Toddy and “Victor” to join the impresario in his office. On the sound track we hear Toddy's pitch and the impresario's skepticism. As “Victor” sings, the acrobat is a tremendous success; he has let go of the secretary and is supporting himself with only the cane in the champagne bottle. As Victor hits a high note, a close-up of the champagne bottle shows it shattering, and a long shot shows the acrobat falling. His fall brings everyone out of the inner office, and the scene ends. “Victor” is a success. The humor of this scene masks its obligatory narrative role.

Later, when King Marchand is attempting to prove Victoria's real identity, his ruse to get into her apartment is presented visually. In the hallway, King and his bodyguard attempt to follow a housecleaner into the apartment. Victoria's neighbor, who is interested only in putting his shoes out in the hallway for cleaning, is a reappearing character. Whenever either King or the bodyguard is in the hallway entering or exiting Victoria's apartment, the film cuts to the neighbor and his shoes. Straight cutaways show his evolving fears, which range from concern about his shoes to fear about the type of friends his neighbors have. Inside the apartment, the potential consequences of Victoria and Toddy's discovery of King develop the tension that is the source of the humor.

All of the comedy in this lengthy sequence is visual, and thus the editing is crucial. Cutting away from the action to provide necessary plot information keeps the sequence moving. The twists and turns of the plot are highlighted by ample close shots and visual juxtapositions that give the sequence a visual variety that differentiates it from Chaplin's style of filmed pantomime performance. In this sequence, performance is important, but the staging and editing are the sources of the humor. Repetition of characters and situations—for example, the neighbor and his shoes—helps to flesh out the sequence and add humor. The neighbor is not necessary to the narrative story; his only purpose is comic. Both narrative and comedy fuse in this sequence. We discover that King knows “Victor” is really a woman (the narrative point of the scene), and we've had an amusing sequence that entertains while informing.

CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

A comparison of The Lady Eve and Victor/Victoria reveals the decline in the importance of the spoken word. Dialogue, whether comedic or not, is no longer written as Sturges, Wilder, and Raphaelson wrote dialogue. Although also true of television programming, television commercials, and media presentations, films in particular now rely more on the visual for humor than they did in the past. This shift away from the verbal is evident in Victor/Victoria. Visual comedy implies a greater role for the editor than verbal comedy does.

The pace of the cutting for comic effect in The Lady Eve is not very different from the pace in Victor/Victoria. In addition, both films emphasize cutting that highlights character-related sources of humor. In a sense, both films are about gender politics, and just as Sturges was quick to emphasize the primacy of Jean/Eve over Pike, so too was Edwards quick to cut to King Marchand's unease and insecurity when he thinks he is falling in love with a man.

Editing to highlight the source of the tension and therefore of the comedy was a primary concern for both Sturges and Edwards. Surprise and exaggeration are critical dimensions in the creation of their comedy. The editor does not play as important a role in the comedy sequence as in other types of sequences. However, as the work of both Sturges and Edwards illustrates, the editor can make a creative contribution to the efficacy of comedy.