CHAPTER 2

GUIDELINES FOR GOOD PRACTICE

How well you master the Improvement Kata pattern depends to a considerable degree on how you practice. It involves more than just repeating the Starter Kata a large number of times.

This Is About Something Called “Deliberate Practice”

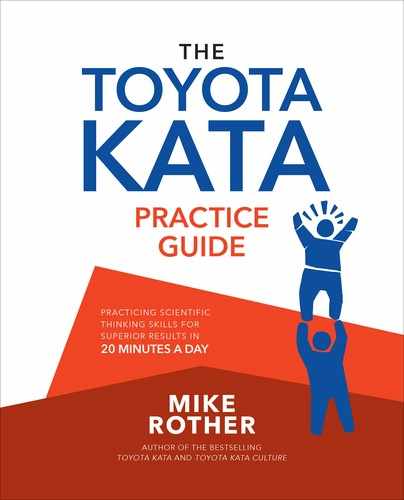

Deliberate practice is practice that is designed to improve performance through a cycle of Doing → Feedback → Adjustment (Figure 2.1). Deliberate practice involves identifying your weaknesses and inventing practice tasks to improve those deficiencies, rather than repeatedly doing what you already know how to do. You get better by correcting your errors. In other words, if you are practicing at a level where you don’t make mistakes, then you are probably not improving your skills.

Figure 2.1. Deliberate practice is designed to improve your performance over time by working on mistakes.

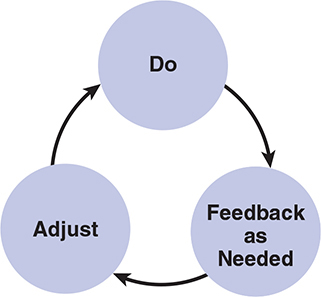

Hopefully you can see that deliberate practice is not just repetition. You should be practicing outside your comfort zone and in your learning zone, where you will struggle and naturally make some mistakes. This is what grows your brain. As shown in Figure 2.2, your learning zone is comprised of skills and abilities—patterns—that lie just beyond your current abilities. No real learning takes place when you practice activities in your comfort zone, since those are patterns you’ve already mastered and are easy for you. Similarly, attempting to practice skills too far out, in the fear zone, is unproductive because you haven’t yet acquired the prerequisites for those skills. As your skill increases, you keep revising your practice in order to keep stretching yourself by staying in your evolving learning zone.

Figure 2.2. To increase skill, practice in your learning zone.

At this point in the story you can probably tell that having someone observe and give feedback on your current performance is critical to understanding what exactly you need to work on next in practicing a new skill. Without feedback, you can get really proficient at doing something badly. This means that deliberate practice is a type of practice that requires a coach.

You’re Going to Need a Coach

The learner needs a coach for at least two reasons. One is that by ourselves we automatically and unconsciously default back to exercising our existing habits, rather than those still-weak new neural pathways we’re trying to build up. The pattern of the Improvement Kata isn’t complicated, but it can be difficult to practice because we’re not used to it and unconsciously tend to revert to the familiar. The other reason we need a coach is that we can’t see and feel what exactly we are doing wrong; we can’t observe ourselves. Perhaps you have had the experience of attempting a new routine again and again and not succeeding until a passerby points out something, which you adjust and then you improve almost immediately. Unfortunately, if you practice the wrong pattern over and over you run the risk of reinforcing weaknesses and making them even harder to change.

Without coaching input, we all too easily lose our way and don’t practice the right pattern, or we practice ineffectively. Without coaching, a change in our mindset—in our brain’s wiring—is less likely to occur. And, as any accomplished musician or athlete can tell you, even as your skills become advanced checkups with a coach will still be helpful for your continued progress.

The Coaching Kata

If practicing the Improvement Kata pattern requires a coach, then where do these coaches come from? We need to develop them!

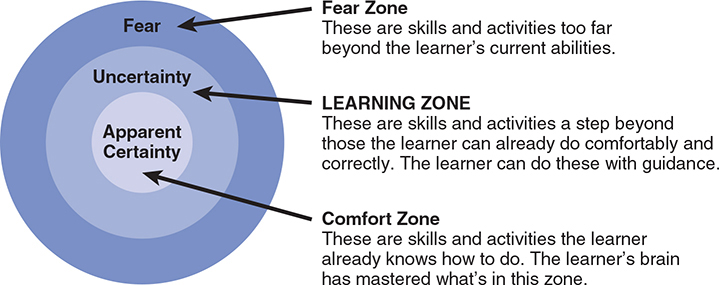

Coaching the scientific pattern of the Improvement Kata is a way for managers to develop their team’s bench strength for achieving the organization’s goals, but coaching is a skill that takes practice like any other. The Coaching Kata is a set of Starter Kata with which managers and supervisors can develop their skill for teaching the Improvement Kata. It’s not a general coaching routine, but a set of practice routines specifically for teaching the Improvement Kata pattern (Figure 2.3). This means that coaches-to-be should first have personal experience in using the Improvement Kata, before they start to coach others, so they are able to evaluate and give feedback on their learners’ Improvement Kata practice.1 But there’s no need to wait to master the Improvement Kata. As soon as you internalize the basics of how to apply the Improvement Kata, you should also start practicing the Coaching Kata and teach others, because doing that deepens your own learning even further.

Figure 2.3. The Improvement Kata and Coaching Kata work together.

The Starter Kata practice routines for the Coaching Kata make up Part III of this book.

In a nutshell, with the Coaching Kata every learner is assigned a coach, who in short, daily “coaching cycles” provides feedback and suggestions on the learner’s effort to apply the Improvement Kata pattern and routines to a real work process. This coaching is done one-on-one. A coach can have more than one learner, but for Improvement Kata practice the coach works with only one learner at a time, because each learner has different weaknesses and practice needs. This coaching is done as part of normal daily work, which means that the coach is probably going to be the learner’s supervisor or manager. Coaching the Improvement Kata is in fact a way of managing. There is no extra staff and no delay before the learner starts to apply the Improvement Kata pattern, which means it is free training. A beauty of the IK/CK approach is that it is relatively easy to apply for immediate benefit, while being rich enough that it takes time to truly master.

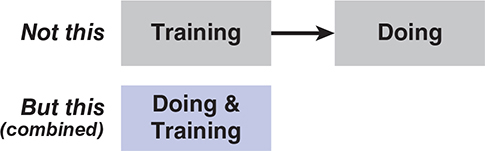

In sports and music, practice and performance are usually separated, but that’s generally not workable in the business world. Here the learner practices the pattern of the Improvement Kata in actual work, and thereby ends up dealing with a healthy mix of real information and problems (Figure 2.4). Practicing as part of daily work means the learner will be applying the Improvement Kata pattern to a real process with real goals. That’s good, because practice is more likely to generate mindset change when the learner focuses on something meaningful—in which the learner has a personal stake—and his or her emotions are involved.

Figure 2.4. Practicing the Improvement Kata on something real is effective for learning.

What the Coach Does for the Learner

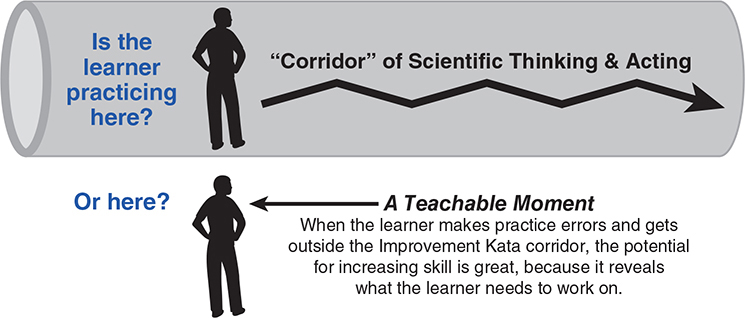

The main responsibility of an Improvement Kata coach is to sense what the learner is ready for next, and to give feedback regarding the learner’s next practice accordingly. Specifically, the coach’s task is to determine whether or not the learner is operating within the “corridor” of scientific thinking and acting specified by the Improvement Kata and its practice routines, and, if not, to introduce procedural adjustments as quickly as possible to get the learner back into that corridor (Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5. The coach guides the learner back into practicing the desired patterns of thinking and acting.

Note, however, that getting out of the corridor is not bad; it’s useful, because wherever we struggle we also learn—improving through errors and correction. The coach expects the learner to get out of the corridor and make mistakes in applying the Improvement Kata, and it is in particular at these “teachable moments” that the coach can give constructive feedback and the learner can advance his or her practice. A lot of us may not enjoy making errors and receiving a corrective input from another person, but that’s actually how you move forward in skill development. In fact, the more you practice the Improvement Kata or Coaching Kata, the more you may feel the urge to say, “Will someone please help me see what I’m doing wrong!” which is a good sign of your growing expertise.

To the untrained eye this may sometimes look like the coach is being directive and telling the learner what to do, but the coach is actually only teaching the learner how to go about striving for goals and solving problems, not solving problems for the learner. This is what we mean by “creating capability.” If managers tell their people what to do, then the capability of the organization is limited to what a few managers know, and they can’t know everything nor be everywhere at once. When managers instead coach their people in an effective, scientific way of handling situations, then the brainpower of the organization is greater.

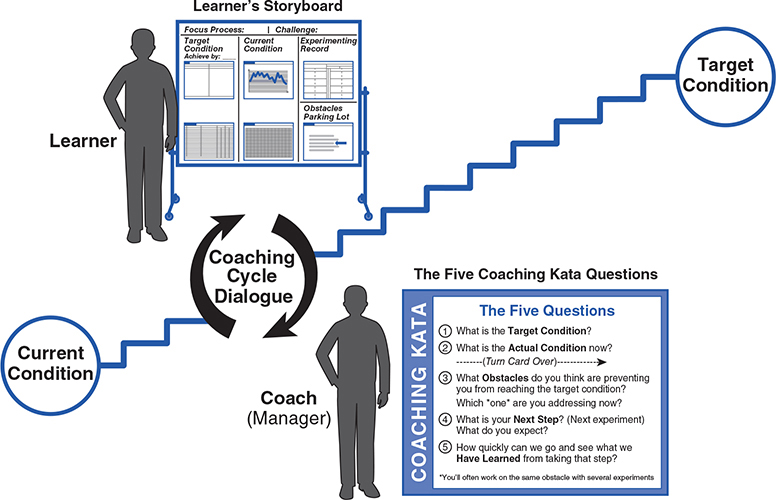

Coaching Cycles, with the Five Coaching Kata Questions and the Learner’s Storyboard

Let’s take a quick closer look at the Coaching Kata, which is covered in detail in Part III.

In order to formulate appropriate feedback, an Improvement Kata coach has to first gain some understanding of how the learner is currently thinking. How can the coach get that insight? In sports and music, the learner’s current skill level is something a coach can readily see or hear. However, the Improvement Kata is about a scientific way of thinking, and thinking is invisible and silent! The Improvement Kata coach discerns how the learner is thinking by asking a set of questions and listening to the learner’s responses, during a structured daily interaction called a “Coaching Cycle.”

A coaching cycle is one of the coach’s Starter Kata. It’s the coach’s main forum and routine for teaching the Improvement Kata pattern.2 A coaching cycle is a short, regularly scheduled, structured face-to-face dialogue between the coach and the learner that is conducted at least once daily, taking 20 minutes or less. The purpose is to frequently review the learner’s approach (their practice) and give feedback as necessary to ensure that it proceeds scientifically. Coaching cycles are used to guide and give immediate feedback and suggestions to the learner as the learner goes through all four steps of the Improvement Kata. These frequent exchanges give managers a way to both develop Improvement Kata skill in their learners and to practice and improve their own coaching skills. They also help ensure that improvement efforts remain focused on the organization’s objectives. Coaching cycles are the “20 minutes” to which this book’s subtitle refers.

The 20-minute coaching cycles are a routine and forum for addressing several issues:

![]() Assessing the current status of the learner’s thinking. The coach asks questions and listens, to help him or her formulate appropriate feedback.

Assessing the current status of the learner’s thinking. The coach asks questions and listens, to help him or her formulate appropriate feedback.

![]() Identifying the current knowledge threshold and making sure the learner plans an appropriate next step that will advance learning. (In the Improvement Kata we like to say that every step is an experiment.)

Identifying the current knowledge threshold and making sure the learner plans an appropriate next step that will advance learning. (In the Improvement Kata we like to say that every step is an experiment.)

![]() Giving procedural feedback to the learner, to help the learner internalize the Improvement Kata pattern by guiding him or her in applying it to a real work process.

Giving procedural feedback to the learner, to help the learner internalize the Improvement Kata pattern by guiding him or her in applying it to a real work process.

![]() Understanding the current status of the focus process, which may be changing as the learner conducts experiments.

Understanding the current status of the focus process, which may be changing as the learner conducts experiments.

![]() Finally, the daily scheduled coaching cycles are a cue for the coach and learner to practice their respective behavior patterns (Figure 2.6).

Finally, the daily scheduled coaching cycles are a cue for the coach and learner to practice their respective behavior patterns (Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6. The Improvement Kata (learner) and Coaching Kata (coach) are two sides of the same coin, and they come together in the coaching cycles.

A coaching cycle is a pause where the coach and learner reflect on the learner’s last step and what has been learned, review the plan for the next step, and introduce adjustments as needed. Problems in the focus process are not solved during coaching cycles. That occurs through the learner’s experiments, which are done in between coaching cycles. Outside of the coaching cycles, the learner may typically spend about an hour a day working on their next step, in preparation for the next coaching cycle. On an as-needed basis the coach may also choose to accompany, observe, and assist the learner during that time, especially with beginner learners.

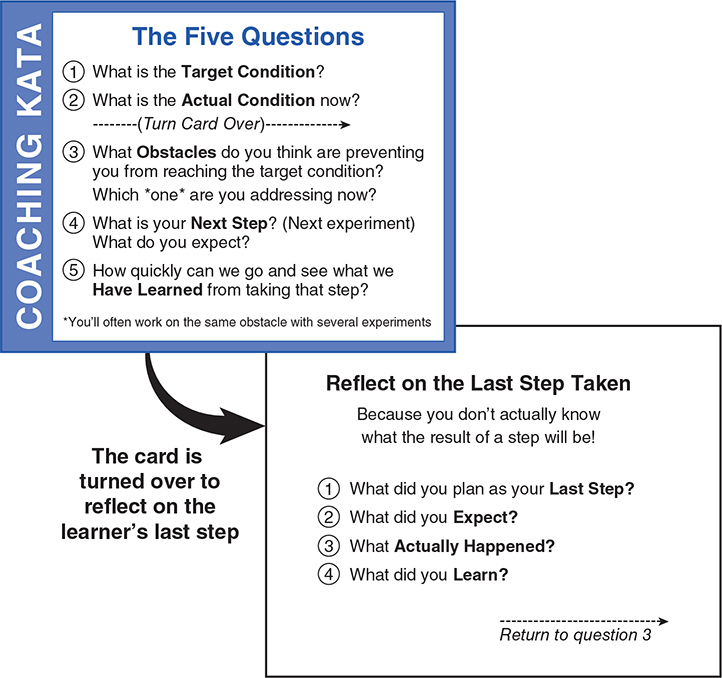

Each coaching cycle is built around a set of questions called the five Coaching Kata questions (Figure 2.7), which is another Starter Kata practiced by the coach. The five Coaching Kata questions are the main headings in a coaching cycle and provide its structure. The sequence of questions mirrors the Improvement Kata pattern and gives both coach and learner a way to help make that pattern second nature. The five questions are easy to learn, and each time you go through them it reinforces the scientific thinking pattern.

However, the main purpose of the five Coaching Kata question format is more than just a reinforcement technique. These structured questions are used by the coach as prompts to help make the learner’s current thinking visible, so the coach can then give feedback that’s tailored to the learner. The main-heading questions are scripted, but the coach’s additional questions and feedback are not. They depend on what the coach discerns about the learner’s thinking. Here’s how it works. In each coaching cycle the coach:

1. Asks the learner the five questions, plus any clarifying questions between the five questions. (This is explained in detail in Part III.)

2. Listens to the learner’s responses to get a sense for the learner’s thinking and identify the current point or points of weakness.

3. Gives specific feedback, as needed, as a corrective input for this particular learner at this particular time.

Since the questions are prompts, simply reading them is not the core skill. Asking the five questions is like a golf coach saying, “Please swing the golf club a few times so I can see what you are doing,” or a music teacher saying, “Please play a bit so I can hear what you are doing.” Since the Improvement Kata pattern is about an invisible mental process, the approach here is: “I’m going to ask you these questions, and how you respond will help me to determine how you are thinking. Then I can give you feedback specific to your situation, so that your next practice is as effective as possible.” That feedback should be specific and purposeful. “You need to draw better block diagrams,” is poor feedback. “Please redraw your block diagram to show the steps and flow of work, not the physical layout of the process,” is good feedback.

Figure 2.7. The coach’s five question card. These questions are the main headings for a coaching cycle (following the scientific pattern of the Improvement Kata) and prompts to help reveal how the learner is thinking (so the coach can give appropriate feedback).

After a few coaching cycles, the learner should see that he or she doesn’t need to be anxious about these interactions, because both learner and coach share the same objective: improve the focus process while also increasing the learner’s and coach’s skills. Traditionally the most feared words an employee might say in response to his boss are: “I don’t know.” In a coaching cycle words like these are actually something the coach is listening for, because they help identify the current threshold of knowledge and where the learner’s next experiment should take place. Scientific thinking involves recognizing and calmly acknowledging what you don’t know, and conducting experiments to find out.

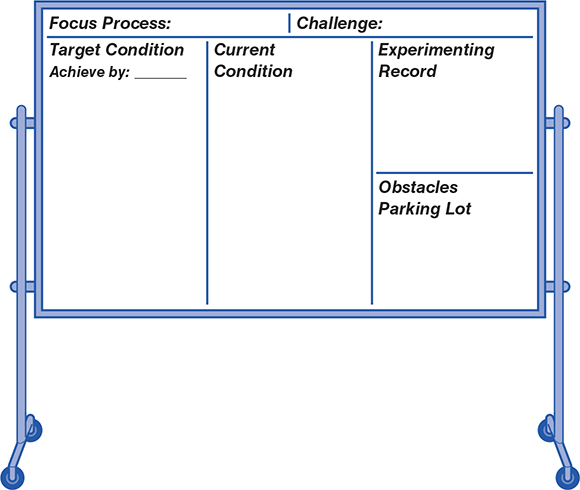

Notice that a coaching cycle is not a “gotcha” exercise, nor a freewheeling ad hoc conversation. The learner already knows what basic questions are going to be asked and prepares her responses in writing before the coaching cycle, in the corresponding fields of a structured, preformatted learner’s storyboard.3 Having the learner do this in advance of the coaching cycle, in writing, also helps the coach understand how the learner is currently thinking.

Figure 2.8. This is the Starter Kata layout for the learner’s storyboard.

The learner’s storyboard is another Starter Kata (Figure 2.8), which is used by the learner in the coaching cycles. The storyboard consolidates information from each step of the Improvement Kata in a structured layout that correlates, from left to right, with the pattern of the five Coaching Kata questions (Figure 2.9). Having the learner prepare, refer to, and actively point to information on their storyboard helps reinforce the Improvement Kata pattern and makes the learner’s thinking process more apparent.

In the planning phase of the Improvement Kata the learner builds up the information on their storyboard one section at a time as the coaching cycle dialogues between the learner and coach go on. In the executing phase of the Improvement Kata the entire storyboard gets referenced, and even updated, with each coaching cycle.

Figure 2.9. The coach’s five questions and the learner’s storyboard work together.

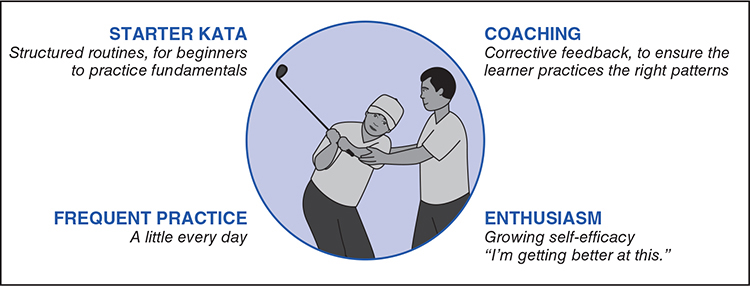

Ingredients for Good Practice

Figure 2.10 summarizes four key ingredients involved in the process of acquiring new skills, which are built into the Coaching Kata. There are other ingredients, too, of course, but anyone practicing or teaching the Improvement Kata should be aware of these four factors in how skill acquisition typically works.

Figure 2.10. Four important ingredients for learning a new skill.

Frequent (“Distributed”) Practice

At the start of the learner’s practice, coaching cycles are done at least once a day. This is because to develop new habits it’s generally better to train for a short time frequently than in massed training sessions. Twenty minutes a day is better than two hours once a week. For example, if you practice the Improvement Kata on only one or two days a week and the rest of the time it’s business as usual, then what you are actually practicing is business as usual. Whatever you practice every day, intentionally or not, becomes your normal routine and habit.

Improvement Kata training is based on daily practice that’s coached by the learner’s manager—making it part of normal daily work—not periodic training by in-house specialists or external consultants.4

Starter Kata

In the previous pages we briefly introduced a few of the Starter Kata used in coaching cycles, which itself is a Starter Kata. If you want to practice, then you need something to practice. A good way to get people to adopt a new behavior in the long term is to start building their ability and self-efficacy through simple, structured routines like the Starter Kata in this book. If you start the learner out practicing a fundamental routine and they feel successful, then they’re more likely to do it again because that behavior gets easier to do. You’re helping the learner develop more ability and more motivation. Then you can have the learner do something harder.

Coaching

The process of learning a new skill involves targeting those aspects of the skill pattern that currently give the learner difficulty and working to correct those points. To tackle their mistakes, the learner needs periodic input from a coach who quickly detects errors and gives advice on how to correct them. Practice errors should be corrected quickly, before they start becoming bad habits.

Enthusiasm

Brain science tells us that the learner’s emotions play an important role in skill acquisition. If we practice but are not enthusiastic about it, then a new pattern probably won’t be learned no matter how much we practice it. In order to move beyond the plateaus that learners inevitably hit, they need to have enough motivation to tackle the mistakes and work through the rough spots. The learner should periodically be feeling “I am getting better at this” so she or he has the positive emotions about practice that are required for reaching higher skill levels. People learn new skills best when they are

passionately interested.

This doesn’t mean that every learner has to be enthusiastic right from the start, or all the time, which would be unrealistic. Rather, it’s the responsibility of the coach to make sure the learner periodically feels a sense of progress and accomplishment, leading to a growing sense of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is a belief in one’s ability to succeed in specific situations or accomplish a task. The learner’s experience of mastery is the biggest factor in determining the extent of their self-efficacy, meaning it develops along the way through the learner’s personal experiences.

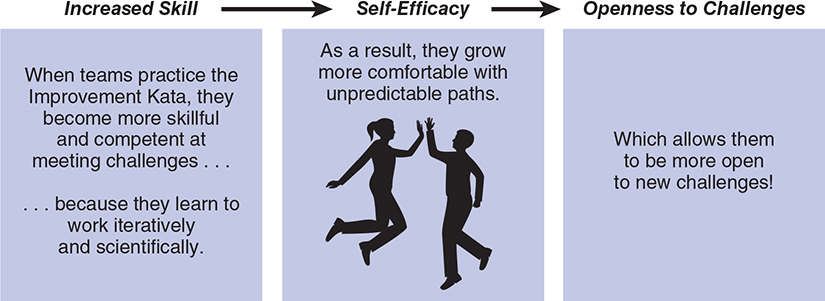

Self-Efficacy—Something to Hold Onto

Practicing the Improvement Kata helps us experience uncertainty more as an opportunity—“I’ve never done that before, but I’ve practiced a way to figure it out and find the way.” This increase in self-efficacy happens because Improvement Kata skill gives you and your team something to hold onto when the path is uncertain. It’s a kind of security blanket that provides stability in the midst of complexity and change.

All of us need something to hold onto and steady us when we step into the unknown. One option is to rely on our preconceived notions, our plan, for how things will go. But the future is not completely predictable. Instead, when people learn a scientific way of proceeding, they can shift from relying so much on their preconceived notions to also relying on a procedure, a means, for navigating the unknown, thereby becoming more open and applying their creativity (Figure 2.11). We still make a plan, of course, but we now view any plan more as just a testable hypothesis. We become more resilient, less afraid of making mistakes and being judged by others, and more comfortable in the learning zone. Practicing the Improvement Kata doesn’t reduce uncertainty, it makes you more comfortable with uncertainty because you’ve mastered a way of dealing with it.

Figure 2.11. This is a chain reaction you’re trying to create by practicing the Improvement Kata.

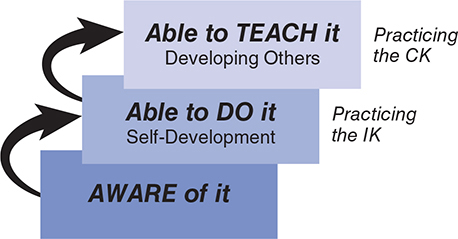

The Typical Path in Learning the Improvement Kata Pattern

Anyone who wants to learn the scientific thinking skill pattern that is modeled by the Improvement Kata will go through a route that looks something like Figure 2.12. Notice that the stages of this progression overlap:

Figure 2.12. The Improvement Kata learning path.

1. Aware of it. At the start you may have basic knowledge about the Improvement Kata model from books, websites, videos, seminars, workshops, and so on. Though you might even be able to describe the steps, you are not able to do the new skill yet. You do, however, have a surface understanding of what it is about.

2. Able to do it. This is where you begin to develop your own skills and alter your mindset. At this level, you are actively practicing and applying the Improvement Kata routines yourself. A goal of this stage is to be able to string together the individual Starter Kata skill elements in behavior sequences and successfully apply the four-step Improvement Kata pattern in a real environment. Importantly, we have found no way to get around this stage before going on to the next stage of coaching others. You have to be a learner before you can teach, at least for a while.

3. Able to teach it. At this point your experience has given you a deeper and more instinctive understanding of the “why” behind the Improvement Kata pattern. Now you can instruct, coach, and counsel others in practicing it. You now find it fairly easy, and even automatic, to integrate scientific thinking into any problem-solving effort, and can easily recognize the lack of it. I encourage you to find a learner and begin coaching the Improvement Kata soon, which will deepen your own learning.

Summary

We’re now two chapters in. The first two chapters talked about scientific thinking and deliberate practice. Bringing those two topics together is the basis for this book (Figure 2.13). The Improvement Kata and Coaching Kata combine a practical, four-step scientific working pattern with techniques of deliberate practice, to turn scientific thinking into a lifetime skill anyone can learn.

Figure 2.13. The concept behind The Toyota Kata Practice Guide.

Combining these two topics is useful for anyone and any team that wants to develop creative, entrepreneurial skills and operationalize concepts like “Learning Organization” and “Systems Thinking.” Practicing the set of Starter Kata in this book is intended to increase your competitive capabilities, because the more you develop skill and confidence in the Improvement Kata pattern:

![]() The more challenges you can take on

The more challenges you can take on

![]() The bigger the challenges you can take on

The bigger the challenges you can take on

![]() The more knowledge you can build

The more knowledge you can build

![]() The faster you can move ahead

The faster you can move ahead

In the next chapter, we’ll look at creating the environment for daily practice.

1 The coach is someone who has been there, done that vis-à-vis the steps and routines of the Improvement Kata.

2 As with any Starter Kata, as skills develop your organization can build on this to suit the characteristics of your environment and culture, as long as the basic pattern and principles remain.

3 The certainty of knowing the basic questions that will be asked helps the learner better deal with the uncertainty inherent in the scientific approach they are practicing.

4 Although practice is daily, there will be plateaus when it seems like you aren’t making progress. At these times the learner can, of course, take a break for a few days or go back to refresh some basics.