CHAPTER 11

CYCLES: CONCEPT OVERVIEW

A Dialogue Routine

Coaching cycles are your primary routine for helping the beginner learner acquire the scientific thinking pattern of the Improvement Kata, and for practicing your coaching skills.1 The next three paragraphs are a quick review.

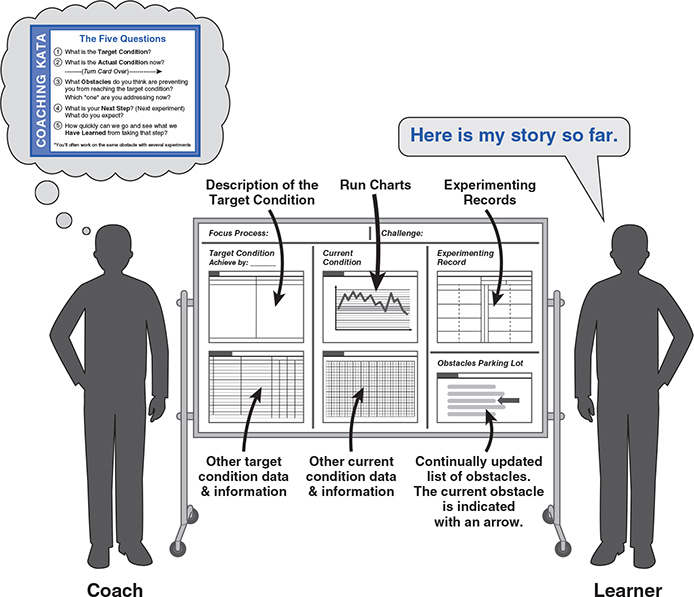

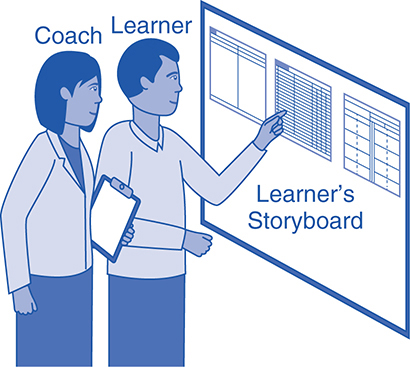

A coaching cycle involves the coach going through the five Coaching Kata question categories with one learner, who refers to information on their storyboard while responding. This is done once per day at a scheduled time, plus as the need arises, taking 20 minutes or less each time—which is the “20 minutes” in this book’s subtitle. Coaching cycles usually start and end at the learner’s storyboard.2

Think of coaching cycles as a pause to reflect on the learner’s last step, review the learner’s plan for the next step, and give feedback, as necessary, on the learner’s procedure. In doing this you are working to nudge the learner’s practice into the corridor prescribed by the scientific pattern of the Improvement Kata, so that, over time, the learner develops a reflex of thinking that way. Coaching cycles help uncover biases in our thinking and introduce changes in how we think, by correcting practice errors quickly, before they become habits. The purpose is not for the learner to “learn the Starter Kata,” but to internalize the scientific thinking pattern behind them.

A coaching cycle is not a free-form conversation, not a rigid fill-in-the-blanks process, and not about policing the learner. The structured and repetitive nature of coaching cycles—especially at the start—is where a dialogue pattern between you and the learner gets established, to help teach the scientific Improvement Kata pattern while using that pattern to meet goals. To repeat from Chapter 2, the purposes of a coaching cycle are:

![]() Assessing the current status of the learner’s thinking, which helps the coach formulate appropriate feedback

Assessing the current status of the learner’s thinking, which helps the coach formulate appropriate feedback

![]() Identifying the current knowledge threshold relative to the obstacle the learner is working on, and making sure the learner is designing a good next experiment to see further

Identifying the current knowledge threshold relative to the obstacle the learner is working on, and making sure the learner is designing a good next experiment to see further

![]() Giving procedural feedback to the learner, to help the learner internalize the scientific thinking Improvement Kata pattern as they apply it to a real work process

Giving procedural feedback to the learner, to help the learner internalize the scientific thinking Improvement Kata pattern as they apply it to a real work process

![]() Understanding the current status of the focus process

Understanding the current status of the focus process

![]() A cue for both the coach and learner to practice their respective behavior patterns and keep improving their respective skills

A cue for both the coach and learner to practice their respective behavior patterns and keep improving their respective skills

Coaching cycles are not all there is to coaching, of course. For instance, the coach can also decide to accompany the learner as the learner takes the next step, in order to observe the learner and/or the focus process more deeply and provide some real-time guidance or support. In the course of a workday, a manager may have many interactions with their learners, and all those interactions can reflect the scientific thinking patterns that are being stressed in the coaching cycles. Over time a manager’s every encounter and interaction should begin to radiate the scientific Improvement Kata pattern, because the everyday behavior of managers functions as a role model and is one of the main forces for creating a deliberate, scientific thinking culture. Coaching cycles are the formal, structured part where it begins.

Try to Schedule Coaching Cycles for Every Day

For each of your learners, schedule a regular coaching cycle at a set time early in the workday, so the learner can carry out their next step that day if possible. It can be a challenge to arrange things so you can do at least one coaching cycle with each learner every day, but it is important to get as close to that frequency as possible. You might think once or twice per week could be sufficient, but that doesn’t work well for developing new skills. Without frequent reflection and feedback, a beginner learner will automatically tend to favor existing habits over still-awkward new patterns. Practicing 20 minutes a day is considerably more effective than two hours only once a week.

As soon as you start getting better at it, daily coaching shouldn’t be a burden. On the contrary, coaching cycles can be an efficient and effective way of managing, and you should be able to conduct most coaching cycles in 20 minutes or less. Remember, a coaching cycle is only for reviewing the learner’s process of experimenting, not for doing the experimenting itself. The learner sees beyond the current threshold of knowledge by taking the next step (experimenting) between coaching cycles, not through theoretical deliberation and discussion in the coaching cycles.

If your coaching cycles consistently take longer than 20 minutes, it may indicate a flaw in your coaching. For instance, novice coaches sometimes mistakenly let coaching cycles get into lengthy discussions or cover many different factors, by treating them more like a meeting. All you need to get to in a coaching cycle is identifying and agreeing on the learner’s next step; that’s it. As soon as a single next step, not a list of steps, is clear to the learner and the coach, then that coaching cycle is done. At that point the learner can go take the next step, which you can review in the next coaching cycle and see further. It is perfectly acceptable for the learner’s next step to be a single and small one, as long as your coaching cycles are frequent. You can make astonishing progress toward goals this way, and unnecessary time spent speculating and opining are eliminated.

Another important benefit of conducting frequent coaching cycles and taking small steps is that it gives coaches the leeway to let their learners make some mistakes and learn from them, because small steps facilitate fast course correction. A key aspect of deliberate practice is that we learn through our struggles and errors, because they show where we need to improve and they engage our emotions. These “teachable moments” are an opportunity for constructive feedback and advancing the learner’s practice. With infrequent coaching cycles a beginner learner will tend to plan and take steps that are too big for swift course correction.

The Five Coaching Kata Questions

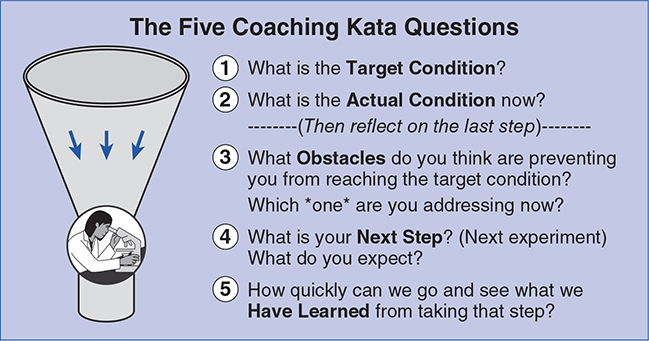

The five Coaching Kata questions are a Starter Kata that provide the framework for your coaching cycles. Going through all five of them, in order, constitutes one coaching cycle. The five questions are nested, meaning that each question is a subset of the previous question. Think of them like a funnel, starting with the target condition. The current condition is then described, relative to that target condition. The current obstacle being worked on springs from understanding the current condition, and then the questioning can focus down to the learner’s next step (the next experiment) relative to that obstacle.

The five questions are the main headings in a coaching cycle. They are like five question categories, and you can ask additional clarifying questions between them. Regardless of what you say between the five questions, at the beginning you should ask the five questions exactly as they are written on your coaching card, letting the overarching pattern sink in and become a habit for you and the learner. For instance, the target condition gets reviewed at the beginning of every coaching cycle as a “frame,” even though this may start to seem repetitive and redundant when you’re doing daily coaching cycles. A pattern you’re trying to ingrain is to always talk first about where you are going (the target condition), and then about aspects of the current condition, and so on, relative to that.

A common mistake beginner coaches make is to deviate from the five Coaching Kata questions. If a learner sees you departing from the five-question pattern, they will tend to do the same, and soon you are both just reinforcing your current thinking rather than developing new routines of scientific thinking. When you get started it’s completely normal to feel awkward following the five-question script. That’s not a reason to deviate from it, but a positive sign that you’re starting to learn something new. Instead, start adding your own “clarifying questions” between the five questions, based on your experiences. There’s more on that in the following pages.

The five questions have great power when you know how to use them and how to respond to the answers you hear. Be careful, though. Simply asking these questions and some elaborating questions does not make you an expert coach. Their structure is easy to learn, but it takes practice and time to master the thinking behind them. As your coaching skill grows, you’ll start to think even more scientifically, add the right questions and, most important, be able to listen to the learner and have approaches for providing effective feedback.

There are Two Main Purposes for the Five Coaching Kata Questions

As a coach it is important to understand the two main reasons why you are using the five Coaching Kata questions in a coaching cycle. The questions (1) reinforce the scientific pattern of the Improvement Kata and (2) are prompts for the learner to show you how they are currently thinking, so you can formulate appropriate feedback.

1. The five questions reinforce the pattern of the Improvement Kata. You repeat the same overall pattern of inquiry in every coaching cycle, to help convey a systematic, scientific way of thinking.

2. The five questions are prompts that help reveal how the learner is thinking. You’re listening for the thinking pattern of the learner as the learner responds, so you can give specific, situational corrective feedback.

It’s like a sports coach asking an athlete to take a few swings or a music teacher asking a student musician to play a few bars, so they can observe what the student is doing. However, since the Improvement Kata pattern is an invisible mental process, the coach relies on questions to observe how the learner is currently thinking. Having the learner update and prepare their storyboard before each coaching cycle is part of this too. It’s not that you don’t trust the learner, it’s that you have to have a way of understanding the learner’s thinking before you can give feedback.

To facilitate this, be sure to take the time to stop talking—to pause—and listen to what your learner says. A common error here occurs when the coach prematurely draws conclusions, rather than waiting to see what conclusions the learner draws. The minds of beginner coaches are often understandably so focused on getting through the five questions that they end up not paying enough attention to what the learner is saying, and whether or not that conforms to the intent of the Improvement Kata pattern. This issue should go away with practice, once asking the five questions becomes habitual and you are able to direct more of your attention to the learner. Try to get frequent practice with the five questions by also using them at other times—for instance in meetings—not just during coaching cycles.

The coach is using a pattern of coaching that looks like this:

1. Ask a question.

2. Listen. Stop and be quiet.

3. Compare. Compare the learner’s responses to the desired pattern of thinking—the “corridor” specified by the Improvement Kata.

4. Instruct. Introduce an adjustment to the learner’s practice if necessary.

Here’s a related story from Coaching Kata practitioner Michael Lombard:

As a novice coach, I would go through and ask those questions verbatim, but I was initially so focused on the questions that I wasn’t really listening to the answers. That’s where my second coach would say, “Inreviewing how the learner answered your questions, take a look at the answers. What more do you want to know about any details they shared that would help explore the situation of what is truly happening here?” My second coach would guide me to slow down. My processing was still deliberate and slow at that point, so I needed to slow down my questioning to leave myself time to think about the answers in the context of the situation. As I got more experienced, those main headings remained as my Kata, but I could more freely expand on the questions where it was needed.

Asking Clarifying Questions

By now you should see that the Coaching Kata is more than just asking the five questions. It’s about getting an understanding of how the learner is thinking. After each of the five questions you can also ask clarifying questions to trigger or probe the learner’s thought process, gain more detailed information, and help identify the current threshold of knowl-edge. Between the five questions is where the coach’s experience with the Improvement Kata comes into play, so the coach can see what the learner is doing right and wrong.

Your clarifying questions should relate back to the one of the five questions you most recently asked, seeking more detail relative to that question category. There are several examples of clarifying questions in the next chapter.

The duration and complexity of your coaching cycles will ebb and flow. In some coaching cycles there may be several questions and adjustments to get the learner’s practice back on pattern, and sometimes a coaching cycle will be just a quick check. With an experienced learner and coach, a five-question coaching cycle can often go quite quickly. However, whenever there is a weak point—where the learner can’t answer one of the five main questions precisely with data—the coach should add some open-ended clarifying questions to get into a deeper and more detailed consideration and response. This is where the learner’s current threshold of knowledge and next step typically become apparent, especially if the learner is reaching conclusions without evidence.

Closed-ended questions are those that can be answered by a simple yes or no—such as “are you sure?”—and don’t give you much information about the learner’s thinking. Open-ended questions require more thought and more than a one-word answer, and begin with words such as how, what, describe, tell me more about, what do you think about? What exactly is happening? How do you know?” You can also use the universal clarifying statement, “Please show me.”

An example closed-ended question is, “Did you measure several exit cycles at the focus process?” while an open-ended question would be, “Can you show me your latest data about the focus process?” Also, be careful asking your learner the question, “Why?” because using this word can easily feel confrontational rather than constructive, especially if you ask it repeatedly. It’s usually better to use clarifying questions that begin with, “Tell me more about . . .” or, “Can you show me?”

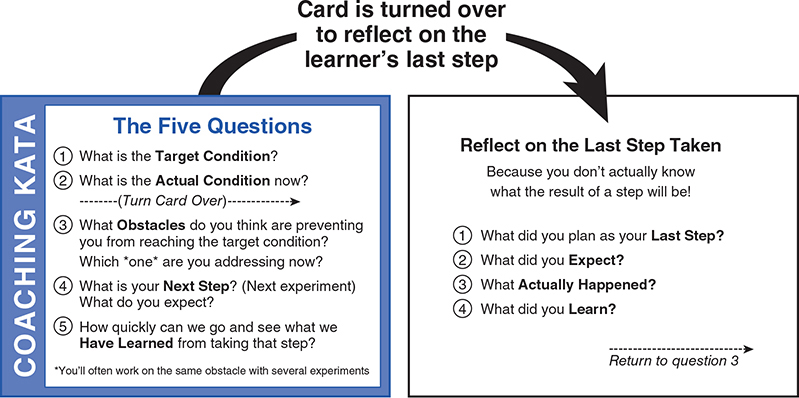

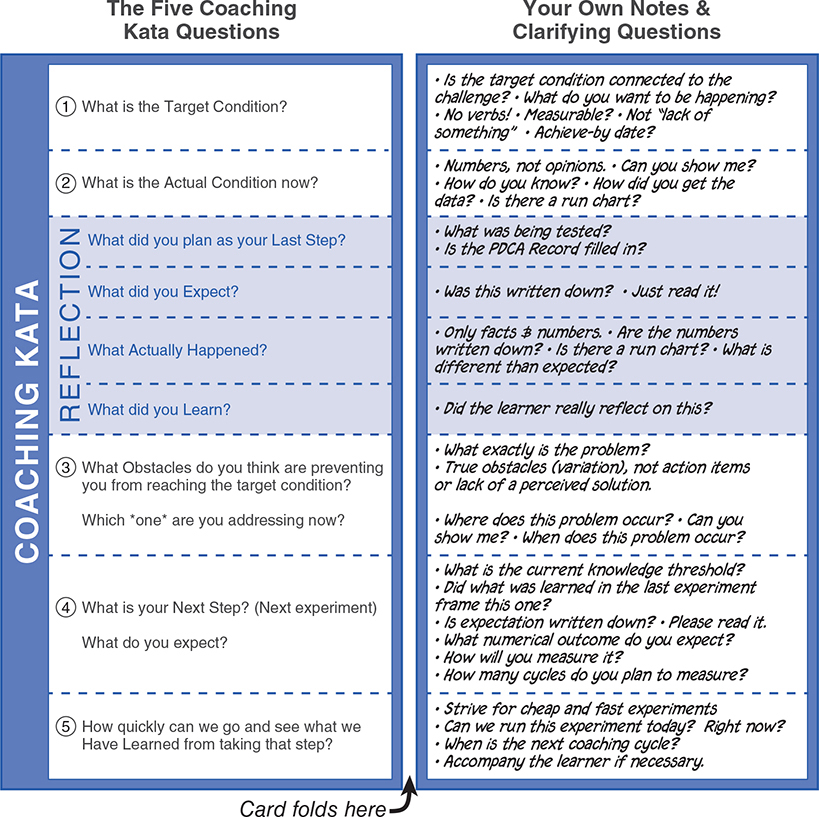

The Coach’s Five Question Card

The pocket card illustrated below is the standard starter card for the coach, containing the basic script for conducting coaching cycles. Keep the card with you as a reference, to be ready for a coaching cycle at any time. The systematic, scientific pattern of the five questions has utility all day long.3

During each coaching cycle, hold the card in your hand and ask all of the questions on the front and back of the card, one at a time and in order. The learner should also have a five question card, since the questions are not a surprise but rather a pattern the learner is practicing. Many learners post the five questions on their storyboard, as a reminder of what to expect in a coaching cycle.

Begin by using the exact five question card that’s shown here. As soon as you get used to what’s on the card, you can start adding clarifying questions based on your experiences and suggestions from your second coach. One way to do this is to make yourself a folding question card like the one shown below. The folded card still fits in your pocket but has space on the unfolded right-hand side to add notes and your own questions that you are testing. The notes and clarifying questions on the example folding card shown here are some thought starters.

The Learner’s Storyboard

The storyboard is the place where the learner records and maintains the ongoing details about their application of the Improvement Kata pattern to their focus process. It tells an unfolding “story,” from left to right, following the pattern of the five Coaching Kata questions, and is used in each coaching cycle to support the coach/learner dialogue. The storyboard also reinforces the scientific pattern of the Improvement Kata and helps reveal the learner’s current thinking to the coach.

Each focus process should have its own storyboard. If a learner is working on multiple focus processes, they will have multiple storyboards. If possible, each storyboard should be located near its focus process, so that you have the option of going and seeing the focus process during a coaching cycle.

Since the storyboard is a Starter Kata, your learner should begin with the exact layout of the storyboard that’s shown here and in the Appendix. This common format also makes it easier for you to communicate with multiple learners. Over time your organization’s storyboard format may evolve to suit your environment, but if you maintain a more or less standard storyboard format—whatever it is—across your organization, then coaching and communication will be easier.

Important: Watch for the Threshold of Knowledge in Every Coaching Cycle

“Knowledge threshold” is an important aspect of scientific thinking, and it comes up in all three parts of this book. A knowledge threshold is the point at which we have insufficient facts and data, and start assuming. There’s a current knowledge threshold for the learner in almost every coaching cycle, related to the obstacle that the learner is trying to overcome.

Finding the knowledge threshold is a key part of a coaching cycle, because that helps you and the learner see what the learner’s next step should be. A good coaching question to have in mind in this regard is, “What do we need to learn next?”

Recognizing the current knowledge threshold can be tricky because a beginner learner naturally wants to answer your questions, rather than saying, “I don’t know.” Ideally you’d like the learner to say, “We’re at a knowledge threshold here. At the moment I don’t know the answer, and I don’t want to jump to conclusions. Here is the next step (experiment) I intend to take to help me get the facts and data we need to learn more.”

You can encourage this kind of thinking by saying things like, “It’s not a problem if you don’t know, just tell me how you plan to figure it out,” or, “How can we find that out?” Scientific thinking depends on being able to acknowledge what we don’t know, so that we know what to test next.

Since the learner may be hesitant to say, “I don’t know,” a knowledge threshold will often be spotted by the coach noticing that the learner is responding imprecisely, with generalizations, assumptions, opinions, or speculation. As a coach you should develop an ear for it. When the learner does any of the following, it may indicate that a knowledge threshold has been reached. These indicators are a cue to focus in at that point, ask some clarifying questions, and encourage the learner to go and see, measure, dig deeper, or conduct a test:

![]() The learner uses words such as I think, probably, maybe, could, most likely, well . . . , on average, 90 percent of the time.

The learner uses words such as I think, probably, maybe, could, most likely, well . . . , on average, 90 percent of the time.

![]() The learner says, “Let’s reduce/increase it by 50 percent.” (A 50 percent “guesstimate” is a typical response when we lack a specific, calculated number.)

The learner says, “Let’s reduce/increase it by 50 percent.” (A 50 percent “guesstimate” is a typical response when we lack a specific, calculated number.)

![]() The learner refers to data that is too old.

The learner refers to data that is too old.

![]() The learner seems overconfident, for instance acting like something must be true without being able to explain why.

The learner seems overconfident, for instance acting like something must be true without being able to explain why.

![]() The learner refers to anecdotes without hard data.

The learner refers to anecdotes without hard data.

At any time in your five-question coaching cycle dialogue, you may become aware of the learner’s knowledge threshold, and at that point the learner’s next step usually involves obtaining more facts and data relative to that point of weakness. Rather than continuing the coaching cycle with assumptions and opinions, you may go right to question 4 and agree on the next step. Don’t let the coaching cycle structure override learning. Stop, have the learner take that step as soon as possible, and use what is learned to see further in the next coaching cycle. Note that this can send the learner back to investigate something they already thought they knew, which is not uncommon.

The key is that you (the coach) are trying to teach your learners that we see further by experimenting, rather than through conjecture. You can encourage this by handling knowledge thresholds with a positive spirit that has the learner:

![]() Acknowledge that knowledge threshold! A key realization is that there’s always a threshold of knowledge.

Acknowledge that knowledge threshold! A key realization is that there’s always a threshold of knowledge.

![]() Capitalize on that knowledge threshold! Congratulations, you found it. Now stop and see further by conducting an experiment. Don’t deliberate over answers in the coaching cycle. Deliberate instead over the design of the next experiment.

Capitalize on that knowledge threshold! Congratulations, you found it. Now stop and see further by conducting an experiment. Don’t deliberate over answers in the coaching cycle. Deliberate instead over the design of the next experiment.

With practice you will not only start to see knowledge thresholds around you all the time, you may even begin to enjoy them as a fascinating part of life and something that helps you reach your goals.

Don’t Take Over the Problem Solving, Help the Learner Practice the Problem-Solving Process

In a coaching cycle, the coach is not asking questions in order to direct the learner to a particular solution (though it can feel that way to a beginner learner), but to guide the learner on procedure. The coach shouldn’t be directive about what the learner is working on. That springs from the learner’s process of experimentation, and neither coach nor learner knows in advance exactly what steps will lead to the target condition. However, once you have listened to the learner’s responses, you can be directive about the learner’s procedure for the next step.

Beginner coaches, especially if they are the learner’s boss, may struggle with the boundary between “coaching” and “telling the learner what to do.” It can be hard to keep from jumping in with your own thinking about solutions, or asking questions to lead the learner toward your preconceived ideas. Always keep in mind that the Coaching Kata is focused on getting the learner to practice thinking scientifically for themselves. Help the learner be more aware of where their problem solving is not a sound scientific process, but don’t take over their problem solving. Ask open-ended questions that seek to learn how the learner is thinking, and then offer feedback on the learner’s procedure that helps bring the learner into the corridor of Improvement Kata thinking and practice. If you are asking questions to lead the learner to your ideas for a solution, stop. But you can and should discuss the content and procedure of the learner’s next experiment, which is not a solution but rather the process of developing solutions.

The Role of Encouragement

Since the learner’s Improvement Kata practice occurs in the real world, rather than in a classroom, it is naturally going to involve setbacks and plateaus. We like to say “continuous improvement” or draw a staircase leading up to the next target condition, but that’s not how it really works. You and your learner should practice every day, but you’re probably not going to get better every day. Also, when we practice a new set of skills we are supposed to feel a sense of discomfort, because we’re engaged in weaving new neural pathways. Practicing in our learning zone is sometimes going to involve feeling awkward, slow, unnatural, stiff, uncomfortable, and difficult.

All this makes encouragement, done right, an important element of coaching. For a beginner learner it’s especially important to derive motivation from periodically feeling that he or she is successfully moving closer to the target condition and getting better at the Improvement Kata. If your learner is not getting this feeling periodically, then something in your coaching should be adjusted.

One key is to give specific praise that emphasizes new learning and growth, not just effort. You might say, “You’re not there yet, but you’re on the right track,” or, “Look how your work has changed since two months ago. It’s clear you’re starting to get the hang of this.” (Be careful, you could inadvertently give the impression that you know the solution but are keeping it a secret.) With every win in overcoming obstacles to the target condition, the learner’s sense that they can accomplish something grows. The learner becomes more motivated to pursue difficult goals and more confident that they will be able to achieve them.

Learn to Adjust Your Coaching Approach5

One of your main responsibilities as an Improvement Kata coach is to sense what the learner is ready for next, and to tailor your feedback accordingly. Don’t assume every learner will pick this up in the same way or at the same pace.

The learner should internalize the patterns built into the Starter Kata, but the structured aspect of Kata practice can be confusing for the coach to handle. How do you and the learner stick to the practice script without getting too robotic? It’s a balancing act. A coach should learn to sense when the learner needs strict structure, and when a more free-flowing dialogue is appropriate. As your skill increases, the nature of your coaching feedback can range from close instructing to looser counseling on a case-by-case basis.

While it is important to get the Starter Kata patterns down, adjustments often have to be made in how you deliver them based on what a learner is saying. Try to let what the learner is saying pull the response from you, rather than you deciding ahead of time what the best way to act would be. You still have to teach the patterns of the Starter Kata, but your delivery can be adjusted.

For instance, you can hold a mental checklist of the five Coaching Kata questions in mind and make sure you get answers to all of them in one way or another during a coaching cycle. You should stay tough-minded on the pattern you are teaching, but you can be softer and more adaptive with the learner. Of course, you should distinguish between a learner who is truly having a hard time adapting to the structured approach of practicing Kata, versus just normal discomfort that comes with practicing any new skill pattern. At the start or when in doubt, stick with the Kata.

The Coach’s Notebook

Many coaches use a coaching cycle notebook to keep track of key issues from their coaching cycles, as reminders for the next coaching cycle with a learner, and to help them improve their own coaching practice. A notebook of some sort is probably a necessity when you are coaching multiple learners. Here are some ideas for what to record on the pages of your coaching notebook:

![]() Name of learner

Name of learner

![]() Coaching cycle date

Coaching cycle date

![]() Start and end time

Start and end time

![]() Focus process

Focus process

![]() Learner’s next step

Learner’s next step

![]() Impressions of the learner’s practice

Impressions of the learner’s practice

![]() Feedback given to the learner

Feedback given to the learner

![]() Notes to yourself: What aspect of my own practice do I need to work on next?

Notes to yourself: What aspect of my own practice do I need to work on next?

The Role and Activity of the Second Coach

If the learner isn’t learning the Improvement Kata or is consistently not achieving their target conditions, then the problem usually lies in the coaching. The apparent simplicity of the five Coaching Kata questions makes coaching seem easier than it is, but it takes practice, with feedback, to master the pattern and intent of the Coaching Kata. It’s the second coach who provides that feedback to you.

As already mentioned, coaching cycles are not just a forum for teaching a learner the Improvement Kata pattern and thinking, but also a forum for you to practice and experiment with your coaching skills. Of course, to make that practice effective, you should have someone to observe you and provide feedback—to “coach the coach.” The second coach does this by observing you doing coaching cycles—to get a grasp of your current practice—and providing feedback to you after the coaching cycle. Having a second coach periodically watch your coaching cycles is essential for you to develop effective coaching skills.

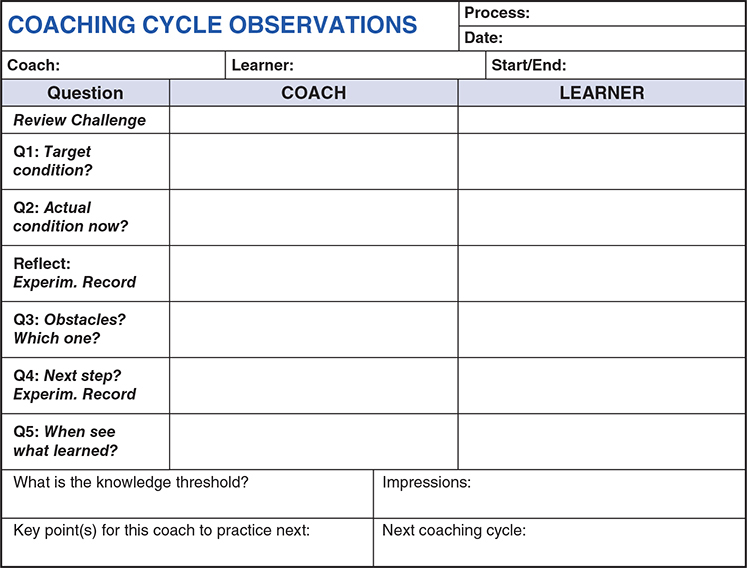

Second Coach: Observing a Coaching Cycle

Good feedback requires good observation, and the second coach should take notes while observing a coaching cycle. The second coach can make an observation form for this purpose, such as the example below. Keep it simple, though, since note taking during a coaching cycle has to be fast. A blank sheet of paper is probably fine at the start.

Some key points for the second coach to look for during observation are:

![]() Is the coaching cycle dialogue following the five Coaching Kata question headings?

Is the coaching cycle dialogue following the five Coaching Kata question headings?

![]() Where is the learner’s knowledge threshold? What is the point of weakness? Did the coach see this?

Where is the learner’s knowledge threshold? What is the point of weakness? Did the coach see this?

![]() Where is the learner’s procedure not following the Improvement Kata? Did the coach see this?

Where is the learner’s procedure not following the Improvement Kata? Did the coach see this?

![]() Where does the dialogue get unstructured?

Where does the dialogue get unstructured?

![]() What did the coach notice and not notice?

What did the coach notice and not notice?

Sometimes it can help illuminate what is going on if the second coach times each step of the coaching cycle. For instance, once a coach and learner have had some practice, their exchange about the target condition and actual condition (Coaching Kata questions 1 and 2) should be short, while the dialogue about obstacles (question 3) and the next step (question 4) usually takes longer.

Like the coach, the second coach should probably also keep a notebook of the coaching cycles observed, to maintain a reference record of observations and feedback given to the coach. One simple way to do this is to keep completed coaching cycle observation forms, plus any other notes, in a binder.

Second Coach: Giving Feedback to the Coach After the Coaching Cycle

Some coaches prefer to get their feedback from the second coach privately, while others like to have their learners there too.6 Be aware that since the learner, coach, and second coach may be in reporting relationships, sending the learner away can give the impression that the coach and second coach are going to talk about the learner. Explain to the learner what you are doing after the learner leaves. Note, also, that it is not the responsibility of the second coach to give feedback to the learner.

Some second coaches structure their feedback in three parts as follows:

1. First ask the coach for their impressions about the coaching cycle that just took place.

![]() How did the dialogue go from your point of view?

How did the dialogue go from your point of view?

![]() Where was the knowledge threshold of the learner?

Where was the knowledge threshold of the learner?

![]() What were you paying attention to in this coaching cycle?

What were you paying attention to in this coaching cycle?

![]() Where did the learner not follow the Improvement Kata pattern?

Where did the learner not follow the Improvement Kata pattern?

![]() Where did you find the dialogue to be difficult?

Where did you find the dialogue to be difficult?

![]() What do you want to pay particular attention to in the next coaching cycle with this learner?

What do you want to pay particular attention to in the next coaching cycle with this learner?

![]() How do you hope this will influence the learner?

How do you hope this will influence the learner?

![]() If you had a do-over on one thing in this coaching cycle, what would you change?

If you had a do-over on one thing in this coaching cycle, what would you change?

2. Then give your feedback, for instance in the following format. Don’t overload the coach; pick one or two key points for the coach to consider and practice next.

![]() “I observed that . . .” (concrete observations you made)

“I observed that . . .” (concrete observations you made)

![]() “I think this results in . . .”

“I think this results in . . .”

![]() “From my point of view you might . . .” (specific suggestion that the coach can practice in the next coaching cycle)

“From my point of view you might . . .” (specific suggestion that the coach can practice in the next coaching cycle)

3. Agree on the date and time for the coach’s next coaching cycle to be observed. A beginner Improvement Kata coach should practice coaching cycles daily, with a second coach observing them each time and giving corrective feedback.

Looking Ahead

This chapter provides a lot of conceptual information about coaching the Improvement Kata. Don’t worry, the pieces fall into place with practice, which we’ll illustrate in the next chapter. In that chapter we’ll go through an example coaching cycle, and then take a closer look at each step of a coaching cycle with the five Coaching Kata questions.

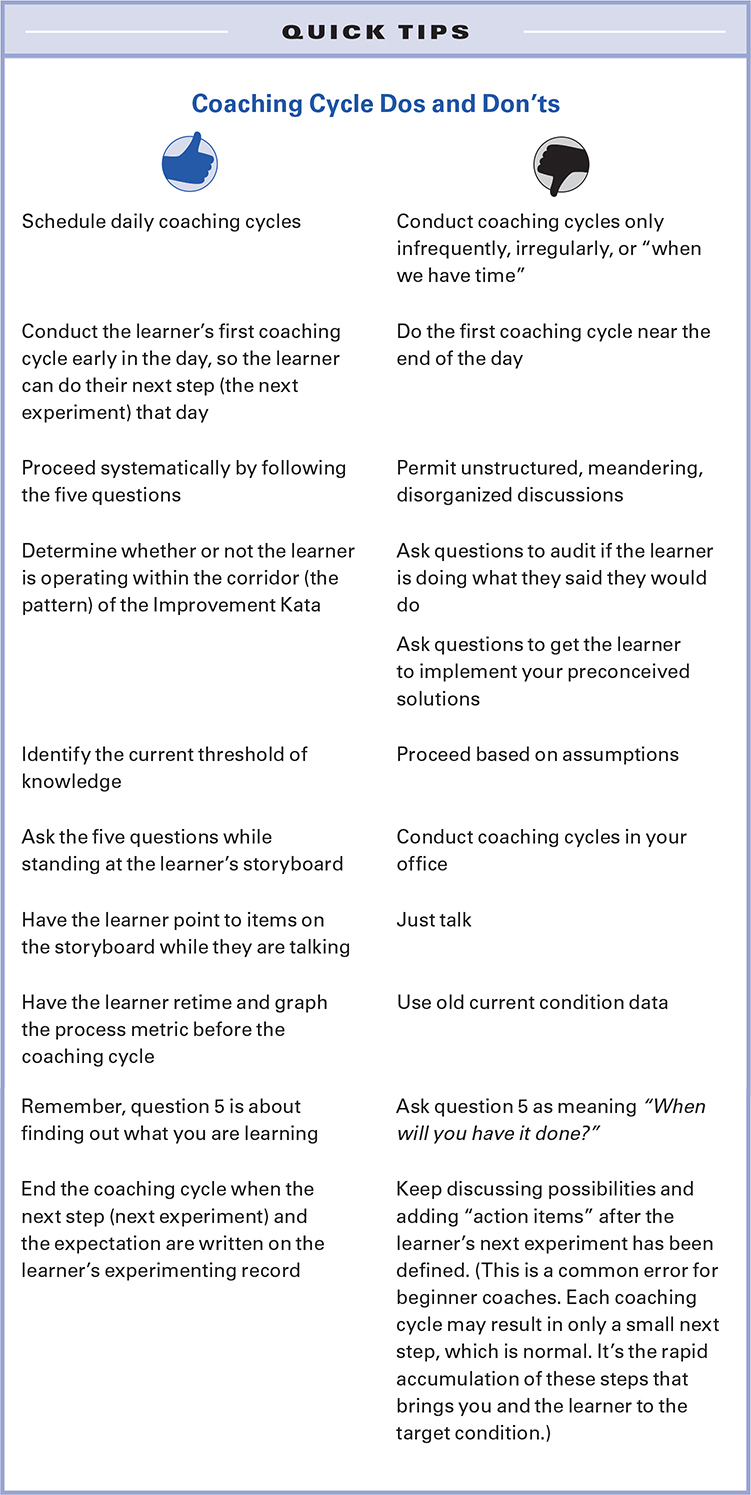

To conclude this Coaching Kata concept overview chapter, there is a set of coaching cycle tips on the next two pages.

1 The Coaching Kata and coaching cycles were introduced in Part I, Chapters 2 and 3, which you might want to reread before proceeding here.

2 Some coaching cycles are also observed by a “second coach,” who is coaching the coach, as explained in the next chapter.

3 A full-size template of the five question card is in the Appendix.

4 There may be an organizational culture bias to look like you have the answer, because people don’t want to appear ignorant in front of the boss. Bosses can change this by practicing the Improvement Kata themselves.

5 The suggestions in this section are from Mark Rosenthal.

6 Some practitioners prefer for the second coach to give immediate feedback to the coach in front of the learner so that all can get over the discomfort of being a beginner.