CHAPTER 1

SCIENTIFIC THINKING FOR EVERYONE

How many times has this happened to you? You notice something out of the corner of your eye, but when you turn to look it’s not what you thought. That cat is actually just a crumpled-up jacket on a chair. The car on your left is only passing you, not actually entering your lane.

What’s interesting about this effect is that our brain didn’t react with, “Not sure what that is . . . need more information . . . please wait.” Instead, it swiftly and without telling us crossed what I call the “threshold of knowledge.” That knowledge threshold is the line at which we no longer have facts and data and start speculating. The unconscious part of our brain takes bits of surface information, extrapolates to fill in blanks, and gives us a sense that we know what’s going on (Figure 1.1). But we actually know a lot less than we think we do.

Figure 1.1. We tend to cross over knowledge thresholds. The brain creates instant judgments using the inputs it receives.

That last paragraph may sound like I’m being critical of the brain’s tendency to cross over knowledge thresholds and jump to conclusions, but the story isn’t so simple. This cognitive mechanism, or cognitive bias, is actually essential for getting us through the day. It’s an energy-saving, better-safe-than-sorry approach that’s beneficial when fast reaction is more valuable than deep understanding. Imagine trying to navigate situations while your brain says, “Please wait until I get more information.” We probably wouldn’t be here today. It’s theorized that we inherited some of our genetic programming from ancestors who quickly ran away from a rustling in the bushes, not from those who turned and said, “Hey, I wonder what that is.”

Yet this useful cognitive mechanism, our intuition or “flying on anecdote,” can also cause a lot of problems. It means we frequently don’t notice our knowledge thresholds—a trap we fall into all the time. It’s a daily balancing act whereby we tend to unconsciously err on the side of jumping to conclusions and living within the parameters of the stories we tell ourselves.1 This is useful for navigating rush-hour traffic, but can also be harmful in our work, society, and personal lives. The ability to stop and think, “Hey, I wonder what that is,” is also essential to our survival and progress as humans, because it is a way of learning.

Scientific Thinking

Fortunately there is a ready countermeasure for our jump-to-conclusions nature. It’s called scientific thinking. That may sound like something complicated and exclusive to professional scientists, but anyone can be a scientist in daily life, including you and me. Scientific thinking is not difficult, it just isn’t our default mode. With a bit of practice anyone can do it, which is what this practice guide is about.

For the purposes of this book we’ll define scientific thinking as a process of deliberately engaging reality with the intent of learning. At the core of scientific thinking is continuous curiosity about a world we will never fully understand, but we want to take the next step to understand a little better. It is a continuous comparison between what we predict will happen next, seeing what actually happens, and adjusting our understanding and actions based on what we learn from the difference (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Here’s the basic pattern of scientific thinking. You make a prediction, reality happens, and if there’s a difference you learn from it.

Scientific thinking is the best way we have to avoid being fooled by our perceptions. You can use scientific thinking yourself, in your team, and throughout your organization to help you achieve goals even though the exact path can’t be fully known ahead of time. You iterate your way forward—always adding to knowledge as you take steps—instead of trying to decide your way forward.

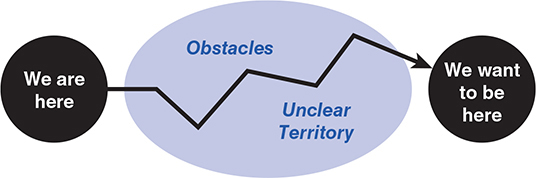

Conditions around us are complex and dynamic, and today’s “benchmark solutions” probably won’t fit tomorrow’s problems. Given these conditions, the best bet for you and your team is to develop a universal “meta skill” for developing solutions in any situation. This is exactly what scientific thinking does, and it may be the most effective means currently known for navigating through unpredictable and complex territory toward our goals (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3. Scientific thinking helps us navigate complex, unpredictable territory.

Scientific Thinking Is Especially Useful Because It Is a Meta Skill

Skills are often domain-specific. You don’t learn to play baseball by practicing soccer. But scientific thinking is a way of working toward any objective. The basic pattern is always the same, regardless of your goal, business sector, or strategy. That makes it a meta skill.

To understand this, separate what you’re working on from how you’re working on it. Meta skills define the how-to, not the what-to. Meta skills tell us how to proceed, but not the content of solutions, and can thus be applied to an infinite variety of situations. Scientists don’t change how they work with each new research topic. The trick is to develop well-worn mental circuits not for solutions, but for a means of developing solutions. This is just like training in sports, where to prepare for unpredictable contests the focus of the training is practicing how to play. That’s meta!

Since meta skills are transferable across different situations, including ones you’ve never experienced before, they can be more valuable than knowledge of a single situation or problem. No one knows what goals and problems your organization will face in the future, so teaching today’s known solutions is not enough. Instead, scientific thinking endows you with skills that can be applied to all sorts of issues and problems you can’t even see yet, over a lifetime.

Born with, or Learned?

Is scientific thinking a talent that some people naturally have, or is it a learned skill? You’ve probably noticed that small children do explore somewhat in the manner of scientists. During that early part of life our brain is highly plastic and is shaping itself through our encounters with the physical and social aspects of our environment.

However, by early adulthood our brain has built up an elaborate web of neural pathways, and it now takes conscious effort to counteract them. As small children we use what we learn from sensory input—from experiments!—to build up our internal structures. As adults, we use those established internal structures to navigate, and we tend to seek out situations that match our internal structures or try to alter our environment to make it match them.2 The child’s mind is learning, and the adult mind is performing.3

In short, once we hit early adulthood we are notoriously bad at scientific thinking, due to the neural library of experiences we’ve constructed that allows us to navigate the world in a way that children cannot. This is both a strength and a weakness for adults. For anyone who has acquired the skills to be able to read this sentence, exploratory scientific thinking is no longer a routine you do naturally. Instead, it’s something we do deliberately in order to check our assumptions and compensate for our biases. Adults learn scientific thinking through intentional practice.

The Improvement Kata—The Four-Step Scientific Pattern We’re Trying to Learn

If you’re going to practice, then you need something to practice.

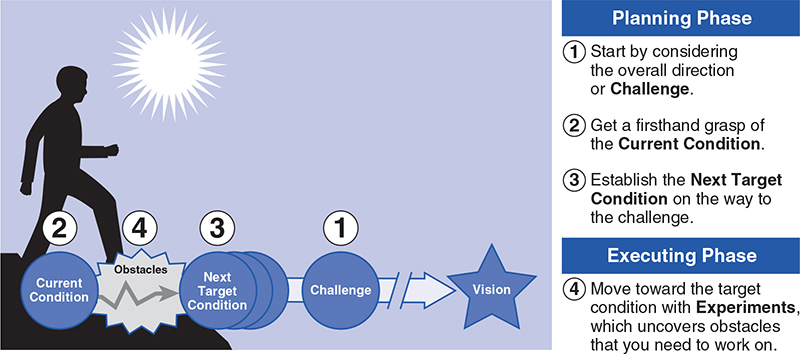

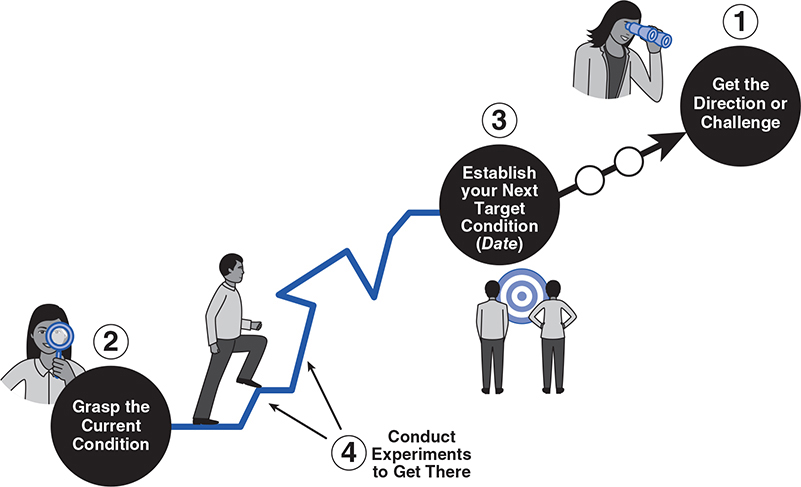

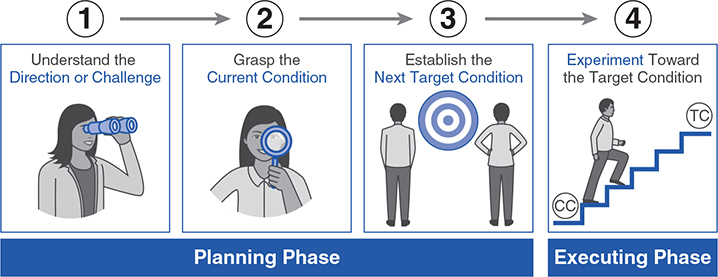

A model is a representation that helps us understand and communicate how something functions in reality. The Improvement Kata pattern is a four-step model of a practical,4 everyday scientific way of thinking and working. It represents the human creative process, which has probably been around for as long as humans have been around. Scientists and entrepreneurs follow something like this pattern every day. The four steps are illustrated in Figures 1.4 and 1.5 on the next page. Let’s take a quick look at each of the four steps of the Improvement Kata.

The Planning Phase

Traditionally we want to jump straight to implementing our ideas, because our brains are already filling in the gaps of knowledge and we often feel certain we know what to do. This is a point, though, where we do want to slow down and say, “Not sure what is going on here . . . need more information.” Taking the time to more thoroughly understand where you are now and establish where you are trying to go will pay off in the long run. The insight and perspective gained in the first three “planning” steps of the Improvement Kata provide the frame or context for effective iteration and discovery in the “executing” phase. There are three steps here:

![]() Understand the direction or challenge.

Understand the direction or challenge.

![]() Grasp the current condition.

Grasp the current condition.

![]() Establish the next target condition.

Establish the next target condition.

The Improvement Kata Model

Figure 1.4. The four steps of the Improvement Kata model.

Figure 1.5. A graphic depiction of the Improvement Kata model.

STEP 1: Understand the Direction or Challenge. Step one defines the purpose for improvement. It’s generally a longer-range goal that will differentiate you from your competitors, typically something customer-focused and strategic that you can’t yet do today. You don’t know how you are going to reach that challenge, and at first it may seem impossible and even a little scary. An overall challenge is typically set at the organization or business unit (value stream) level and gets broken into successively smaller challenges as you move down into the organization.

STEP 2: Grasp the Current Condition. Where are we now? Once the direction coming from the level above you is understood, go to your own focus process and study its current operating patterns in measurable detail. The results of this observation and analysis represent your current knowledge threshold about that process, and are an input into defining the next target condition for it.

STEP 3: Establish the Next Target Condition. Where do we want to be next? Studying the current condition gives you the facts and data you need to establish an appropriate, descriptive, and measurable next target condition for your focus process, in the direction of the larger challenge. A target condition is your next goal and has a much closer time frame than the challenge, usually with an achieve-by date between one week and three months out. You don’t know exactly how you are going to get there, and it may be difficult, but it doesn’t feel impossible. A target condition usually has the following three elements:

1. An achieve-by date.

2. The desired outcome performance of the process—an outcome metric.

3. A verifiable description of the desired operating pattern (how you want the focus process to be operating on the achieve-by date) that you predict will produce the desired outcome performance. This includes a process metric.

While achieving the longer-term challenge can feel overwhelming, having a short-term target condition narrows your focus to the specific obstacles to achieving that nearer condition. Those obstacles are what you will experiment against in step four of the Improvement Kata.

It takes a series of target conditions to reach the challenge, as illustrated by the successive circles in Figures 1.4 and 1.5. Note, however, that those target conditions are defined one after another, not all at once. They are not a predetermined list of milestones or action items. When you reach one target condition or its achieve-by date, the focus process will have a new current condition, you will know more, and then you’ll be in a position to establish an appropriate next, further target condition in the direction of the challenge.

You can’t tell in advance exactly what the chain of necessary target conditions will be, due to your threshold of knowledge, which moves. Making an initial plan may be valuable, of course, but expect it to change as you learn.

The Executing Phase

Having laid your groundwork in the planning phase, you are now ready to execute, fast and focused, with learning and adjusting as you go.

STEP 4: Experiment Toward the Target Condition. Once you understand the current condition and have a next target condition, there is a gray zone, or learning zone, between them. If your target condition achieve-by date is more than a week or two away, you probably need to do some planning. Nonetheless, you still cannot foresee and plan the exact path to a target condition.5 The obstacles you encounter on the way will show you what you need to work on to get there, and you find your path by conducting daily or frequent experiments against those obstacles. You don’t need to work on every conceivable obstacle, only those obstacles that you actually find are preventing your focus process from operating in a way consistent with the next target condition. This is advantageous because you minimize wasting your time, capacity, and resources trying to fix everything. In fact, you’ll learn the discipline of ignoring some problems.

The path to the target condition will not be a straight line. You’re in a mode of rapid learning and discovery to progressively learn how to get to the target condition. From each experiment you may gain new information and adjust your next step accordingly. Be ready to accept that the path may be different from what you expected, and don’t waste time arguing about who has the best solution. Argue instead about what may be the best next experiment for learning more and seeing further as quickly as possible.

When you reach the target condition achieve-by date, you’re in a new position. There is a new current condition, and the four steps of the Improvement Kata now are repeated.

The Overall Pattern

The Improvement Kata model can also be depicted linearly, as shown in Figure 1.6. In the linear representation the planning phase and executing phase become visible.

Based on the descriptions of the three planning steps, you should notice that “planning” in the Improvement Kata is different from the traditional leap to making an action plan. A common mistake is trying to get into the executing phase too soon—rushing into implementation based on preconceptions. Instead, you take some time to analyze and learn more about the situation. Compared to a traditional businessperson who may be in a hurry to lay out an action plan, a scientific thinker might say that a problem clearly defined is half solved.

Figure 1.6. A linear depiction of the Improvement Kata model.

As you use this book, always keep in mind that the Improvement Kata pattern is not a problem-solving method, but a mindset; a way of thinking in problem solving. There are many good problem-solving methodologies, and practicing the Improvement Kata supports them all. Notice that no matter what kind of problem solving you are doing, you’re going to have these conditions:

![]() A goal that you have not yet reached

A goal that you have not yet reached

![]() Obstacles to that goal

Obstacles to that goal

![]() Solutions that don’t yet exist (otherwise you would have already implemented them)

Solutions that don’t yet exist (otherwise you would have already implemented them)

![]() A need to test your ideas

A need to test your ideas

The Improvement Kata pattern doesn’t replace your improvement methods. Its purpose is to build the foundational scientific thinking skills that make you even better at whatever problem-solving or improvement methodology you are using. Practicing the Improvement Kata integrates well with existing methods and approaches because it is about the underlying thinking.

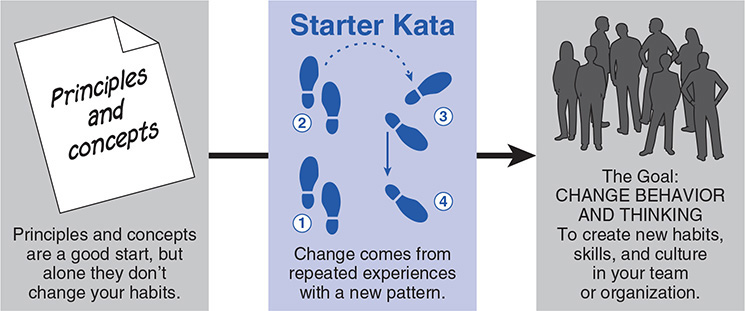

What Are Kata?

Here are two slightly different definitions for the Japanese word Kata. We’ll use both. Notice how definition 1 (a pattern) without definition 2 (practice routines) is unlikely to change behavior and mindset:

1. One definition of Kata is a suffix meaning “way of doing.” For instance, the Japanese word kakikata means “way of writing” or “how to write.” This definition pertains to the four-step Improvement Kata model or pattern, which is a way of improving. Think of this as the “macro” definition.

2. Another definition of Kata is a “structured practice routine or drill.” This is the “micro” definition.

That second definition of Kata refers to small, predefined practice routines, or drills, of fundamentals that help get us started in adopting a new way of acting and thinking. For clarity’s sake, let’s differentiate that definition by calling them “Starter Kata,” meaning they are the first basic practice routines you begin with. You practice Starter Kata (micro) in order to learn the scientific way of thinking depicted by the Improvement Kata model (macro).

Practicing Starter Kata has been utilized for centuries as a way of preserving effective skillsets, transmitting them from person to person, and building effective teamwork. Having a set of Starter Kata is particularly useful when you want to create a shared way of thinking and acting, a deliberate culture, among a group of people, because everyone begins with practicing the same fundamentals.

Starter Kata are stepping-stones for acquiring new habits of thinking and acting, but practicing them does not mean becoming permanently rigid. The intent of formally practicing some structured Starter Kata is not to hem you in, but to help set you on a new path (Figure 1.7). The goal is to internalize each Starter Kata’s fundamental pattern so you can then build on and adapt that pattern under a variety of circumstances as a reflex, with little thought or hesitation. For example, as a musician you wouldn’t stick with playing a musical scale forever, but you wouldn’t change that Starter Kata either. You go beyond it by building on what you learned from practicing it. The next learner who comes along begins with the same Starter Kata. Of course, over time each organization can fine-tune its own set of Starter Kata, which it finds work best for its particular environment and culture. This book gives you the starting point.

Figure 1.7. Starter Kata (micro definition) are like booster rockets. They’re practice routines that help you along in developing new ways of thinking and acting.

The process is like the way you probably learned to handle an automobile. After practicing the basics of the automobile’s controls for a while, perhaps in a parking lot, you no longer had to purposely think about how to operate them. Today you can apply your finite cognitive resources to navigating the real road outside of the automobile because you have learned to handle the basic controls inside the automobile more unconsciously as a habit. Mastering fundamentals—making them automatic—frees our brain to focus its limited resources on the less repetitive situational aspects that do require conscious attention.

Many of us dislike structured starter routines and would like to improvise immediately, but that’s a mistake that can leave you a permanent beginner. By initially restricting practice improvisation the learner acquires a sense for the essence, which the learner can then apply in increasingly diverse situations. Ultimately, then, the Starter Kata are not the important thing. What are important are the skills and mindset that practicing them imparts, which you can then build upon.

Summary: Benefits of Practicing Starter Kata

![]() They help beginners start to acquire a new skill by providing simple predefined, step-by-step practice routines for internalizing fundamentals.

They help beginners start to acquire a new skill by providing simple predefined, step-by-step practice routines for internalizing fundamentals.

![]() They give the coach a point of comparison for gauging the learner’s performance and providing corrective feedback and suggestions.

They give the coach a point of comparison for gauging the learner’s performance and providing corrective feedback and suggestions.

![]() They help to develop a shared mode of thinking and acting across a team or organization by providing common routines for everyone’s initial practice.

They help to develop a shared mode of thinking and acting across a team or organization by providing common routines for everyone’s initial practice.

![]() Perhaps most important, Starter Kata help bridge a gap by translating theoretical principles and concepts into something real and teachable (Figure 1.8).

Perhaps most important, Starter Kata help bridge a gap by translating theoretical principles and concepts into something real and teachable (Figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8. Starter Kata help you turn concepts into something real.

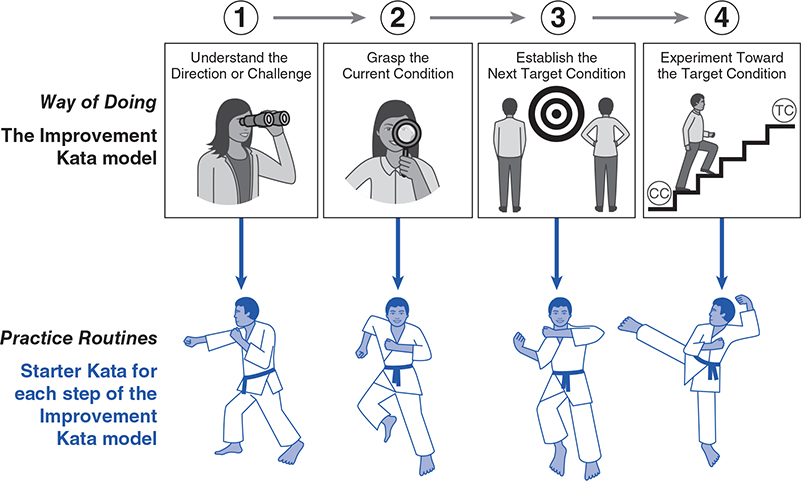

Practice Develops New Habits

Attempting to generate a different behavior in someone by explaining it, demonstrating it, or trying to convince a person about the need for it usually doesn’t work. We don’t think and behave unscientifically because we lack information about the pattern of scientific thinking, but rather because unscientific thinking is our habit.

The brain strongly prefers our established neural pathways, and trying to counteract them with logic or inspiriation usually doesn’t work. The learner will almost always automatically stick with or revert back to an old way of thinking, especially when stressed or under pressure. Not because he or she is being hostile, but because it’s physiological.

Consider this: The four-step Improvement Kata model is similar to other models of the creative scientific process such as Creative Thinking (1920s), Learning Organization (1970s), Critical Thinking (1980s), Design Thinking (1980s), Solution Focused Practice (1980s), Systems Thinking (starting in the 1990s), Preferred Futuring (1990s), and Evidence-Based Learning (1990s).6 These and other models have been promoted in the business world for decades, yet they have had little impact on the way most businesses are led and managed. Despite countless books, articles, presentations, and courses, surprisingly few organizations have operationalized these concepts and principles. For most people, a model alone—like the Improvement Kata model—is not enough. The issue is how to change our behavior and mindset to what the model depicts.

What we know can work for learning new ways is to deliberately practice a new routine. With the right kind of practice, it is possible to build new habits (new neural pathways) that eventually replace the old ones and shift how we think and act—even as adults. As brain scientists like to say, “Every time you do something you are more likely to do it again.” Or, to put it another way, “We are all much more likely to act our way into a new way of thinking than to think our way into a new way of acting.”7

However, don’t expect to be an expert on your first try with a new way! When you set out to learn a new skill, you are going to be a beginner for a while (though only in that particular area), and you start by working on some basics. This is where the Improvement Kata goes further. Each step of the Improvement Kata model also comes with structured practice routines—Starter Kata—that help individuals, teams, and organizations operationalize its scientific thinking pattern (Figure 1.9).

Figure 1.9. There are Starter Kata practice routines for each step of the Improvement Kata model.

The Starter Kata practice routines for the four steps of the Improvement Kata model make up Part II of this book.

Keep in mind that Starter Kata are a skill-development approach. There is no such thing as “implementing a Kata,” only “practicing a Kata.” The Starter Kata in this book are learning mechanisms that are used to teach and acquire a scientific way of thinking and acting, and in the long term to help modify the culture of an organization as its members develop a new set of shared beliefs and habits.

Stages in Practicing a Starter Kata

When you practice a particular Starter Kata, it can help your initial discipline if you keep the following progression of three stages in mind. In reality, of course, Kata practice won’t have quite such distinct and linear phases. Even experts move back and forth between the stages, returning to following a particular Kata in order to refresh some basics. The stages will also intermingle, since a learner will probably have different skill levels with the different Starter Kata. Nonetheless, they are a useful way to help you understand what you are trying to do when you practice a Starter Kata.8

Starter Kata Stage 1: FOLLOW. The first phase is to mimic the Kata—to repeat the specific practice routine exactly as described without modification. Initial practice of any new pattern uses your slower conscious mind, like the first time you tried to use the rearview mirror in an automobile. This can make the practice seem awkward and forced, but resist the temptation to deviate from it at this point. That uncomfortable feeling is a normal part of learning something new, and is actually what you should be feeling at this stage. It’s a sign that you are building new neural pathways. To experience this feeling right now, try crossing your arms opposite the way you normally do, or signing your name with your nondominant hand.

What would happen if you practiced crossing your arms or signing your name this new way every day for a couple of months? Even if you don’t agree with or don’t understand something, you can still do it. You’ll understand later. Accept doing it, and once the Starter Kata’s pattern enters your unconscious and becomes more habitual it will get faster, smoother, and easier. Think of the “follow” practice stage as going slow to get fast.

Starter Kata Stage 2: FLUENCY. In the second phase, the pattern of the Starter Kata becomes natural and you don’t have to think about it as much. As your proficiency grows, you come to understand the purpose behind the practice routine. Your decisions and actions become more unconscious, and your brain’s resources are freer to focus on the situation. You’ll start to add your own maneuvers to this element of scientific thinking and automatically begin to apply it to several aspects of work and life.

Starter Kata Stage 3: DETACH. You enter the third phase when you can break away from the formal Starter Kata while sticking to its underlying principles, because you have internalized them. In this phase you use the knowledge you’ve acquired to create your own approaches and develop your own style.

A great thing about practicing Starter Kata is that it is “learning with the body.”9 If you try to convince someone to adopt a different managerial or work practice, you are trying to fight the existing neural highways that make up their established habits. Instead, you begin by getting the learner to just do it, in a structured, prescribed fashion at the start. Its a way to make scientific thinking more natural, because in learning with your body you engage a whole set of experiences, senses, and emotions. When you learn a skill with the body it builds new habits that become hard to forget, like riding a bicycle.

Two Common Error Modes in Practicing with Starter Kata

1. The Permanent Beginner. This error arises when we think we are too skilled to learn and are unwilling to practice things that feel awkward to us. Suppose you have already practiced an improvement approach that now comes naturally to you. You might feel an aversion to mimicking predefined, structured starter routines and immediately want the freedom to improvise—to change the pattern of a Starter Kata before you’ve taken the time to learn the basics it imparts. Without first resigning our ego to practicing some basics, we’re destined to remain a beginner in that area.

2. The Implementer. This error arises when we think of a Starter Kata as a method to be implemented and thus permanently stick with its structured routine, rather than seeing it as an initial step in the process of developing new skills. As mentioned, you can’t implement a Kata, you can only practice it.

How Long Do You Practice a Starter Kata Before You Achieve Some Fluency and Can Start to Vary Its Routine?

This question sometimes comes up, but cannot be answered precisely because it depends on each learner’s progress. The idea is for the learner to reach some proficiency before deviating much from the prescribed Starter Kata routine. Generally speaking it might take about 15 hours of deliberate practice, with correction, to shift from being a beginner to basic fluency in the new skill element. (Note that basic fluency does not yet get you to the detach stage.) If you practice 20 minutes every day at work, this could take about two months of practicing a particular Starter Kata. Of course, you’ll be practicing more than one Starter Kata at a time.

With regard to learning the overall four-step Improvement Kata pattern, one practical guideline is that a learner should work on at least three successive target conditions at one focus process (three passes through the entire four-step Improvement Kata pattern) and have conducted at least 25 experimenting cycles in step four of the Improvement Kata. This number of coached repetitions—assuming more or less daily coaching cycles10—may be enough to begin developing the Improvement Kata pattern as a new habit.

What Comes After the Starter Kata?

As you advance to proficiency with the patterns embedded in the Starter Kata, they should become part of how you normally think and work, in a natural, automatic, habitual way. By developing deeper and unconscious understanding, you’ll apply the Improvement Kata pattern more on autopilot.

Once you internalize the Starter Kata, you’ll develop a growing and delightful ability to quickly sense what is now most important—in other words, what is the next step—in a situation.

You’ll be able to recombine and build on skill elements in ways that suit the characteristics of a particular situation, and even develop your own style, all while keeping the essential patterns of the Starter Kata intact.

This does not mean that learning ends. You’ve begun a lifetime of practice that keeps on deepening your skills. Learning the core skills and underlying purpose is the basis for applying them in situations that are more complex or different from what you are accustomed to and that defy rote application. The Starter Kata are explicit knowledge, and now you work on developing the tacit knowledge that comes with experience. Your repertoire increases when you do this, and you may even enjoy flexing your skills in diverse or difficult areas that are new to you.

You’ll be working on your coaching skills and even coaching other coaches by taking on the second coach role. It may surprise you to learn that coaching others will deepen your own scientific thinking skills further and even faster.

Don’t be surprised if you find yourself spontaneously expanding the application of scientific thinking to other aspects of your life. This can lead to feeling critical of others when they jump to conclusions rather than thinking scientifically—although, from your own practice of the Starter Kata, you know it does not come naturally, and you know how one can change that!

Summary

We’ve introduced the idea that you need to practice in order to develop greater scientific thinking in yourself, your team, and your organization. In the next chapter, we’ll look at some of the elements and characteristics of effective practice.

1 This catchphrase is by Professor Ralph Williams, University of Michigan.

2 For more on this subject, read the Introduction to the book Brain and Culture by Bruce E. Wexler (2006, MIT Press).

3 This saying is from our colleague Jeremiah Davis.

4 I use the word practical because a traditional scientist experiments in order to understand, whereas an Improvement Kata practitioner experiments to move toward a goal.

5 Making a detailed project plan doesn’t eliminate uncertainty, it only provides an illusion of certainty. If you go to business school and learn an analysis and planning process, that’s only half of the matter. You should also learn a good iteration process.

6 If you squint, all these models look about the same. There’s a good reason for that: all of them are about human striving.

7 Richard T. Pascale, Mark Millemann, and Linda Gioja, “Changing the Way We Change,” Harvard Business Review, November–December 1997.

8 In the martial arts these stages of practice are called Shu-Ha-Ri.

9 Thank you to our colleague Pierre Nadeau for introducing us to the phrase “learning with the body.”

10 Coaching cycles are introduced in the next chapter.