CHAPTER 12

HOW TO DO A COACHING CYCLE: PRACTICE ROUTINES

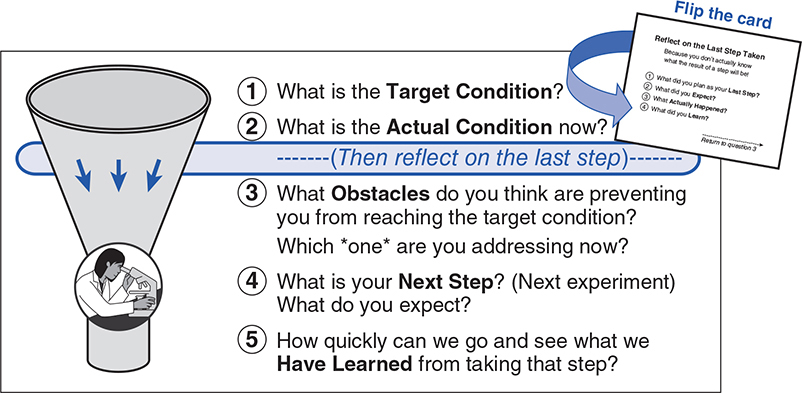

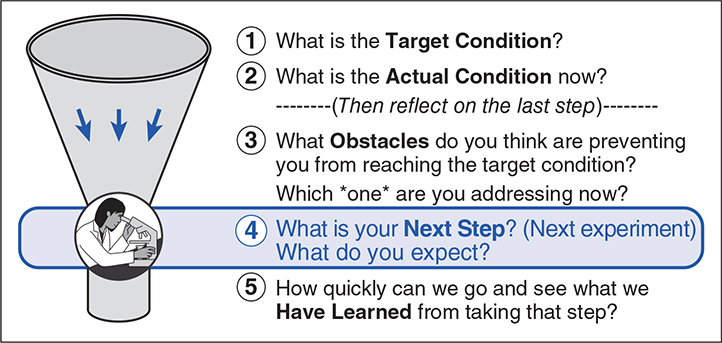

This chapter shows you what to do. It (1) walks you through an example coaching cycle, and then (2) reviews each step of a coaching cycle, with the five Coaching Kata questions as the headings of those steps. (The examples in this chapter are in the “executing” phase of the Improvement Kata.) This chapter includes the following information.

After each coaching cycle you should review how it went and decide what aspect of your coaching you want to work on in the next coaching cycle. Feedback from your second coach is invaluable in this. However, the extra edge in practicing any skill comes from working on something that you personally want to get better at. In the case of coaching, that extra edge may come from your truly wanting to help learners be successful in developing and applying their own scientific thinking. Create power in your people!

Your Overall Goal as a Coach: Giving Useful Feedback to the Learner

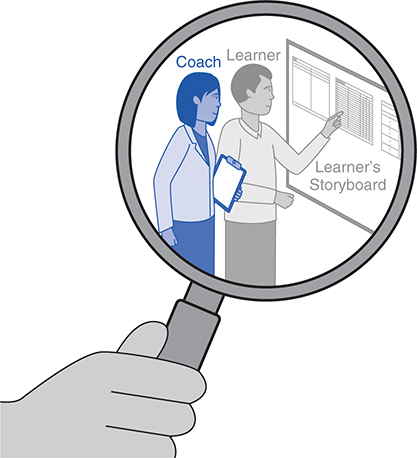

Let’s start with the end in mind. The purpose of a coaching cycle is to review the learner’s practice of the Improvement Kata and give useful feedback, as necessary, on the learner’s procedure. There can be some content character to your feedback, too, of course, without getting into solutions. For example, you might show the learner how to make a run chart or how to arrange information on their storyboard.

Feedback is usually communicated between you and the learner, and anyone else whom you and the learner want to have present. In some coaching cycles your second coach will also be there, but this person is observing your coaching practice. The second coach does not give feedback to the learner.

The flow and elements of a coaching cycle are structured, but feedback to the learner is situation dependent, different from coaching cycle to coaching cycle and learner to learner. As you improve your coaching mastery, your feedback will get better. Imagine your task as a coach as determining whether or not this learner is practicing within the corridor of scientific thinking and acting procedure that’s specified by the Improvement Kata, and to introduce course corrections as necessary to get the learner back to practicing “on pattern.” Your feedback should be based on observation, should be specific, and should pertain to what the learner is doing or not doing, not to the learner’s traits or characteristics as a person (this has nothing to do with the learner as a person). Your feedback can be reinforcing or corrective:

![]() Reinforcing feedback praises practice done well and encourages the learner to continue to strengthen that behavior. Be specific about what is good and why.

Reinforcing feedback praises practice done well and encourages the learner to continue to strengthen that behavior. Be specific about what is good and why.

![]() Corrective feedback points out an area of the learner’s practice that should be modified to avoid building a bad habit, and gives specific advice for how the learner should modify their practice.

Corrective feedback points out an area of the learner’s practice that should be modified to avoid building a bad habit, and gives specific advice for how the learner should modify their practice.

You’ll find that there are two categories of feedback in a coaching cycle: Small, quick feedback that involves little tweaks to the coaching cycle dialogue itself, and forward-looking feedback that pertains to the learner’s next step. Both of these kinds of feedback can be given in one coaching cycle—and often are, especially with beginner learners.

1. Small, immediate corrective input on the learner’s way of presenting information in response to the five Coaching Kata questions.

This is quick “pause and fix” feedback that’s done at any time in the coaching cycle to immediately correct unscientific aspects in what the learner is saying or doing right now—in the coaching cycle. Just like in music instruction, it’s important not to play through mistakes and develop bad habits. When you spot unscientific thinking or behavior, or thinking and behavior that doesn’t follow the Improvement Kata pattern, briefly pause the coaching cycle to introduce an adjustment in how the learner is responding.

After you interrupt a coaching cycle like this, immediately rehearse the problematic part by going back to your last Coaching Kata question and restarting there, or even back to the beginning of the coaching cycle. This “let’s start over” technique from music practice helps internalize desired thinking patterns. However, pausing and interrupting a coaching cycle can be overdone, so pick your priorities. Note also that pausing and starting over should in no way seem punitive. You should give it a friendly, caring, and simple “Oh, let’s fix this now” feeling.

2. Feedback for the learner’s next step.

This is the main feedback and adjustment in a coaching cycle, which is often done at the threshold of knowledge. Once you and the learner recognize the current threshold of knowledge, regardless of where you are in the coaching cycle you’ll often go right to question 4 and discuss the next step that the learner proposes, to help see beyond that point. Don’t overload the learner with comments and activities here, either. Just focus on their next step and what you want them to practice. You’ll be back tomorrow.

An interesting alternative strategy is to sometimes not correct the learner’s planning for the next step, even though it contains an error that you see, and instead allow the learner to make the mistake and let the experience be the teacher. This works best when the learner’s next step is cheap, small, relatively harmless, and quick. You’ll have to decide on a case-by-case basis on what occasions to use this approach.

In giving feedback be sure to (a) first describe specifically and clearly what you observe—what the learner is doing or not doing—and then (b) provide a specific and purposeful instruction about how the learner could or should proceed differently. Don’t withhold the rationale for your feedback and just give corrective feedback, but also raise the issue you see that is leading to that particular feedback.

As you read this example coaching cycle dialogue and the subsequent debrief between the coach and second coach, notice what didn’t go well in the coaching cycle.1

Learner: Dan

Coach: Tina (coaches the learner)

2nd Coach: Ron (coaches the coach)

![]()

Ron is heading over to the Sales Department, where he has promised to observe some of Tina’s coaching cycles as her second coach. On the way, Ron thought about what he wanted to watch for. In his first few coaching cycle observations he found it difficult to watch the coach/learner dialogue and think about it at the same time. For this reason he’d made a list of observation tips for second coaches, which he was now mentally reviewing:

![]() Is the dialogue following the five-question pattern?

Is the dialogue following the five-question pattern?

![]() Where is the learner’s knowledge threshold in this coaching cycle?

Where is the learner’s knowledge threshold in this coaching cycle?

![]() What is the point of weakness?

What is the point of weakness?

![]() Where is the learner’s procedure not following the Improvement Kata?

Where is the learner’s procedure not following the Improvement Kata?

![]() Where does the dialogue get unstructured?

Where does the dialogue get unstructured?

![]() What did the coach notice and not notice?

What did the coach notice and not notice?

Coach Tina greeted Ron as they met for a few minutes before the next coaching cycle, “Thank you for coming and taking the time to review my coaching practice. My next coaching cycle is with Dan, who’s working on shortening the lead time for processing sales contracts.” Tina and Ron headed off together to Dan’s storyboard.

Tina and Dan’s Coaching Cycle

Tina: “Good morning, Dan. I’ve asked Ron to watch my coaching today, to give me some feedback afterward. Is that all right with you?”

Dan: “No problem. Good morning, Ron.”

Tina: “Before we get going, can you remind us about your focus process and the challenge?”

Dan: “Sure. I’m currently focused on sales contract processing, and our challenge is to have processing a contract take 20 minutes or less. This is part of a larger challenge for the whole Sales value stream that we call Sale today, closed today.”

(Tina now refers to the Five Question Card she is holding.) ![]()

Tina: “OK, what is the target condition for this process?”

Dan: “The target condition is that the data entry portion of handling a sales contract takes 6 minutes or less, by June 15.”

Tina: “What is the actual condition now?”

Dan points to a run chart on his storyboard: “At the moment it takes between 32 and 41 minutes to process a sales contract. The data entry portion of that is too long.”

Tina asks a clarifying question: “What does ‘too long’ mean in numbers?”

Dan: “The last days have been really busy, and I didn’t have time to measure the data entry time for the contracts we’ve recently processed. But when we measured it two weeks ago and made this run chart, data entry took between 11 and 15 minutes.”

(Tina now flips over her five question card and asks the reflection questions on the back of the card.) ![]()

Tina: “What did you plan as your last step?”

Dan: “I set up some timing for several cycles of sales contract processing.”

Tina: “What did you expect?”

Dan: “I wanted to get a sense for the steps and times for this process.”

Tina: “What actually happened?”

Dan (pointing): “I was able to get the basic steps and their times. As you can see in the run chart from two weeks ago, there was a lot of variability.”

Tina: “What did you learn?”

Dan: “I learned that data entry is usually the single largest block of time in processing sales contracts.”

(Tina flips her five question card back over to the front side and continues with the questions there.) ![]()

Tina: “What obstacles do you think are preventing you from reaching the target condition, and which one are you addressing now?”

Dan reads through his entire obstacles parking lot, then goes to the current focus obstacle: “Data entry is too complex. Sometimes it takes too long to enter the list of customer items; other times it’s something else.”

Tina asks a clarifying question: “What exactly is the obstacle?”

Dan: “I don’t know exactly. It’s different each time, since every customer order is different.”

Tina: “What is the reason for the data entry taking so long?”

Dan: “I think the entire manual data entry process takes a lot of time, as well as the review of the article numbers. Maybe this process could be automated if someone from IT took a look at it.”

Tina: “What is your next step?”

Dan: “I’ll talk to the guys in IT and ask them to look at it. Maybe then we can find a way to reduce the data entry time.”

Tina: “What do you expect from this step?”

Dan: “To know what part of data entry can be automated.”

Tina: “How quickly can we go and see what we have learned from taking that step?”

Dan: “If I can talk to our colleagues in IT today, then maybe tomorrow or the day after. Let’s meet again in three days. By then I should have something.”

Dan made a note of the agreed-on next step and date, and they ended the coaching cycle.

After Dan went back to his work area, Tina asked Ron, “What do you think? How did the coaching cycle go?” She was curious to hear his feedback.

What Do You Think?

Ron and Tina’s discussion after the coaching cycle, as well as Ron’s feedback to Tina, follows below. Before reading that, think about your answers to the following questions:

![]() Where is the learner Dan’s threshold of knowledge in this coaching cycle?

Where is the learner Dan’s threshold of knowledge in this coaching cycle?

![]() If you were coach Tina, what feedback would you give to Dan?

If you were coach Tina, what feedback would you give to Dan?

![]() What do you predict that Ron’s feedback to Tina will be?

What do you predict that Ron’s feedback to Tina will be?

Feedback from Second Coach Ron to Coach Tina

Ron checked his notes, thought for a moment, and said to Tina: “I observed that you and Dan didn’t really have a good grasp of the obstacles, and the next step you agreed on is pretty vague and will take a long time. Dan seems to be jumping to an automation solution.”

Ron went on with a list of points: “I think it’s important to agree on a specific, concrete obstacle first, and then agree on a precise next step related to that obstacle. The problems that the obstacle causes should be measurable, since otherwise the learner can’t formulate a measurable expectation for their next step. I think it’s also helpful to agree on significantly smaller steps. You and Dan should actually be meeting for another coaching cycle tomorrow.”

Tina replied (somewhat impatiently), “Yes, I noticed that too. That was the problem. Dan didn’t know the obstacles well—simply calling the data entry process ‘complex.’ So I wanted to get him down to at least one obstacle. And then the next step somehow got too big. But I didn’t know what else to do. Honestly, your feedback here is not helping me much. What should I do differently?”

Ron noted that Tina was pushing back, so he said, “I do need to learn more about observing coaching cycles. Let’s use your dialogue with Dan to think about what good feedback should look like. We now have both views on the coaching cycle—yours from inside and mine from the outside.”

Tina responded. “I agree, we both noticed the same problem, but I’m not sure what to do about it.”

Ron thought about it. “Generally speaking, your feedback to the learner should relate to the point of weakness in the coaching cycle, which is usually going to be the threshold of knowledge. The threshold of knowledge in your coaching cycle seemed to be at question 3, the obstacles.”

Tina jumped in: “Ah, and at that point I probably should have shifted the dialogue to the next step, instead of continuing to drill down on the obstacles, which Dan doesn’t yet understand well enough. If I push, he’s going to come up with some answer, rather than saying, ‘I don’t know,’ since I’m his boss.”

Tina continued: “In my own Improvement Kata practice I learned that at a knowledge threshold we have to actually go and take a step in order to learn more and see further. Discussing opinions doesn’t help. Sending Dan back for closer observation and investigation of the obstacles would have been a better next step, because that was the threshold of knowledge in our dialogue.”

Ron added, “Exactly. And maybe the threshold of knowledge started appearing even earlier, since the data on the actual condition was not up to date. The last measurements were taken two weeks ago.”

Tina agreed: “True, that was another weak point that I didn’t pick up on. Hmm, now there are two potential thresholds of knowledge. So what should I have focused on?”

Ron: “Both of the issues are connected. Not having up-to-date data makes it difficult to identify true obstacles, which makes it almost impossible for the learner to formulate a measurable expectation for their next step.”

“I’ve come to the conclusion that good coaching cycle feedback should concentrate on one sticking point in the dialogue, at the threshold of knowledge. If possible, the feedback should pertain to the first point of weakness that arises in the dialogue, since the five Coaching Kata questions nest within each other and progressively focus in, like a funnel. If one question is not answered well enough, then the answers to the following questions will be even worse.”

Tina summed up: “I observed that Dan’s data on the actual condition was not current. Without data to study it became difficult to identify specific obstacles. If I notice that actual condition data is not up to date and that’s the knowledge threshold, then at that point I should go straight to question 4. The next step is to get and analyze current data. In fact, whenever we hit the knowledge threshold, we can pretty much go to question 4.”

“I agree,” replied Ron. “And since Dan would be gathering data for a run chart, you can encourage him to also make notes on his timing worksheet about obstacles he observes.”

“Depending on how far into the five questions you are when you hit the knowledge threshold, there may be no need to keep going with all five questions. At that point you and the learner can plan the next step accordingly, agree on the time for the next coaching cycle, and then the coaching cycle is done. You’ll be back for the next one tomorrow, or even sooner if you and the learner would like.

“Once you find the current threshold of knowledge, don’t be afraid to step out of the five question sequence and discuss the learner’s next step to remedy that point of weakness. And the learner should then take that step as quickly as possible!”

Start a Coaching Cycle by Putting the Learner at Ease

It can be uncomfortable to be a beginner. You feel unsure, lose a sense of identity, and become vulnerable. Novice learners may even perceive coaching as meaning they did something wrong. Don’t start a coaching cycle by jumping right into the five questions. Start with building some trust and understanding, showing the learner that you are interested in them and their success, and enabling you to be helpful.

A coaching cycle does not judge success or failure. Both the coach and the learner should have a genuine interest in achieving the target condition, how the learner is proceeding, what is being learned, and what will be the next step. It’s a dialogue, not an exercise of authority. As you get started:

![]() Begin by greeting one another.

Begin by greeting one another.

![]() When you can in the coaching cycle, stand next to the learner, facing their storyboard, rather than facing one another head-on.

When you can in the coaching cycle, stand next to the learner, facing their storyboard, rather than facing one another head-on.

![]() With a new learner, briefly go over the practice and coaching approach so the learner understands what is taking place: you’re practicing skill patterns to make them a habit. Many of us practice with more interest and motivation when we know what we’re doing and why.

With a new learner, briefly go over the practice and coaching approach so the learner understands what is taking place: you’re practicing skill patterns to make them a habit. Many of us practice with more interest and motivation when we know what we’re doing and why.

One key to putting the learner at ease can be to help the learner realize that it’s normal to be a beginner when you’re starting to learn a new skill, just like an athlete. As mentioned above, it may be a good idea to remind yourself and the learner about the purpose of a coaching cycle, which is to develop the learner’s scientific thinking skills by offering procedural feedback, based on observation, on his or her Improvement Kata practice.

Your learner will naturally try to be skillful right from the start with the Improvement Kata routines, especially if you are their boss. So it helps if you create a mindset that it’s OK to make mistakes—of enjoying the discovery and learning process. If you like, you can even point out that you are practicing and learning your coaching routines too.

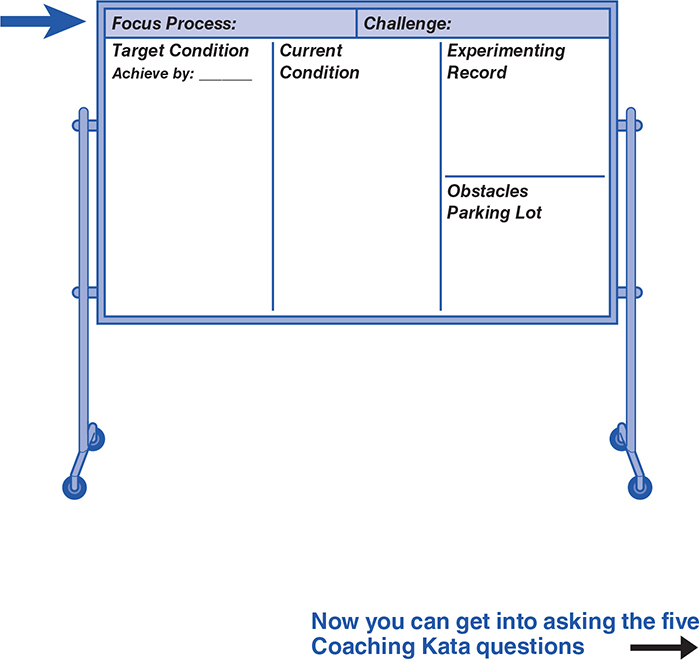

Ask the Learner, “What Is the Challenge?”

Before you begin the five-question coaching dialogue at the storyboard, have the learner name their focus process and reiterate the overarching challenge or goal that he or she is working toward. This reminder connects the learner’s target condition to a larger objective and helps the learner recognize how their efforts fit in with the bigger picture. The rest of the coaching cycle dialogue will be anchored by the challenge.

QUESTION 1

FRAMING AND ANCHORING

Orienting Yourselves

Consensus on both the target condition (Question 1) and current actual condition (Question 2) is essential for avoiding endless discussion. What is the learner trying to achieve, and where exactly are they now? The first two questions are simple and can often be answered quickly, but they are important because the other questions relate back to them.

![]() Don’t skip over questions 1 and 2, even if it starts to feel a bit like play-acting. Go through all five questions in each coaching cycle, because you are framing the dialogue and trying to convey the thinking pattern inherent in the five questions. Many new coaches ask, “Do I really need to ask question 1 every coaching cycle?” The answer is yes, because the rest of the coaching cycle relates back to that question. It only takes a few seconds.

Don’t skip over questions 1 and 2, even if it starts to feel a bit like play-acting. Go through all five questions in each coaching cycle, because you are framing the dialogue and trying to convey the thinking pattern inherent in the five questions. Many new coaches ask, “Do I really need to ask question 1 every coaching cycle?” The answer is yes, because the rest of the coaching cycle relates back to that question. It only takes a few seconds.

![]() The learner should point to their target condition form and read the target condition as it is written there.

The learner should point to their target condition form and read the target condition as it is written there.

![]() There should be no verbs or action items in the target condition, nor should it describe a lack of something. It should describe a measurable destination.

There should be no verbs or action items in the target condition, nor should it describe a lack of something. It should describe a measurable destination.

![]() If possible, the target condition should be in alignment with the challenge that’s noted on the storyboard. It should be a step in that direction.

If possible, the target condition should be in alignment with the challenge that’s noted on the storyboard. It should be a step in that direction.

![]() There should be both an outcome metric and a process metric that will tell the learner when the target condition is achieved. The process metric should be directly observable at the focus process.

There should be both an outcome metric and a process metric that will tell the learner when the target condition is achieved. The process metric should be directly observable at the focus process.

![]() Do you (the coach) understand the target condition? If it is not clear to you, or if the learner cannot explain it clearly, it is likely the learner is not clear about the target condition either.

Do you (the coach) understand the target condition? If it is not clear to you, or if the learner cannot explain it clearly, it is likely the learner is not clear about the target condition either.

“Please read through the target condition.”

“What do you want to be happening?” “How will you know?”

“What is the pattern you’re trying to achieve?”

“What are the intended process steps and sequence?”

“What is the achieve-by date?

“How do you picture the target condition?”

“Tell me about how this target condition relates mathematically to the challenge.”

“Can you describe the target condition with numbers?”

“Let’s run through the math on this.”

“How are you measuring it?”

“What is the process metric? What value do you want it to have?”

“What is the outcome metric? What value do you want it to have?”

![]() The learner didn’t prepare the storyboard before the coaching cycle to ensure that the required updated information is ready and in a sequence that matches the five Coaching Kata questions.

The learner didn’t prepare the storyboard before the coaching cycle to ensure that the required updated information is ready and in a sequence that matches the five Coaching Kata questions.

![]() The learner states a solution or countermeasure as the target condition, rather than describing a desired new state of the focus process.

The learner states a solution or countermeasure as the target condition, rather than describing a desired new state of the focus process.

![]() The learner sees the removal of an obstacle as the target condition, rather than describing a desired future condition. That is, the learner describes the target condition as something that will not be happening, rather than what will be happening.

The learner sees the removal of an obstacle as the target condition, rather than describing a desired future condition. That is, the learner describes the target condition as something that will not be happening, rather than what will be happening.

![]() The target condition is only an outcome metric, without a process metric or any description of a desired operating pattern.

The target condition is only an outcome metric, without a process metric or any description of a desired operating pattern.

![]() The description of target condition is vague and not measurable.

The description of target condition is vague and not measurable.

QUESTION 2

FRAMING AND ANCHORING

Orienting Yourselves (Cont.)

Understanding the current condition is vitally important, both initially and ongoing. Many mistakes can arise when the learner does not measure and maintain an up-to-date understanding of the current condition as changes are made.

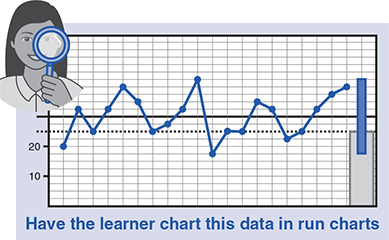

At question 2 be sure to review the current values for the process metric and the outcome metric. These are the minimum metrics that the learner should have updated and graphed, ideally in run charts, before each coaching cycle.

![]() After the first few coaching cycles, for question 2 the learner should no longer be referring back to the initial current condition. The learner should describe the condition now, based on recent direct observation and measurement.

After the first few coaching cycles, for question 2 the learner should no longer be referring back to the initial current condition. The learner should describe the condition now, based on recent direct observation and measurement.

![]() Question 2 is not a review of steps the learner has taken. The learner should simply describe how the focus work process is actually operating now, relative to the target condition.

Question 2 is not a review of steps the learner has taken. The learner should simply describe how the focus work process is actually operating now, relative to the target condition.

![]() As always, ask the learner to physically point at the relevant supporting documents and data on their storyboard.

As always, ask the learner to physically point at the relevant supporting documents and data on their storyboard.

![]() Check that you can directly compare the target condition and the current condition. This is a common problem.

Check that you can directly compare the target condition and the current condition. This is a common problem.

![]() Ensure there is current data for the outcome metric and process metric. Ideally they are in run charts.

Ensure there is current data for the outcome metric and process metric. Ideally they are in run charts.

![]() Whenever possible you should go and see what the learner is talking about. “Show me” and “Tell me more about . . .” are useful coaching phrases at any point in the coaching cycle.

Whenever possible you should go and see what the learner is talking about. “Show me” and “Tell me more about . . .” are useful coaching phrases at any point in the coaching cycle.

“What are the latest facts and data for the current condition now?”

“How do you know?”

“Can you show me the data?”

“Please show me the block diagram.”

“Please show me the run chart of the process metric.”

“Let’s go and see.”

From this point forward in the coaching cycle a useful question can be: “What do you think?” Remember, you’re asking such questions to see if the learner is thinking scientifically according to the pattern of the Improvement Kata. An answer like, “I think we’re not sure yet” is scientific, whereas answers such as, “I think what’s going on is . . .” may represent unscientific conjecture, unless the learner is stating that as a hypothesis that the learner plans to test.

To see if the learner’s actions are based on facts and data, not assumptions, you can always ask: “How can you tell?”

![]() The actual condition on the learner’s storyboard is not actual any more.

The actual condition on the learner’s storyboard is not actual any more.

![]() The learner bases their description of the current condition on opinion, hearsay, and assumptions about what they think is happening.

The learner bases their description of the current condition on opinion, hearsay, and assumptions about what they think is happening.

![]() The description of the actual condition is not based on any data.

The description of the actual condition is not based on any data.

![]() Process and outcome metric run charts are missing on the storyboard.

Process and outcome metric run charts are missing on the storyboard.

![]() The learner is not actually going to the focus process to see the real current condition.

The learner is not actually going to the focus process to see the real current condition.

![]() The current condition description includes words like no, none, or lack, which indicates the learner already has a solution in mind.

The current condition description includes words like no, none, or lack, which indicates the learner already has a solution in mind.

![]() The learner is not directly comparing the actual condition to the target condition.

The learner is not directly comparing the actual condition to the target condition.

Reflect

REVIEWING THE LEARNER’S LAST STEP

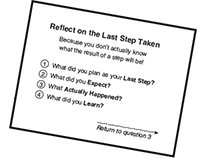

Now turn to and use the “reflection section” on the back of your five question card.

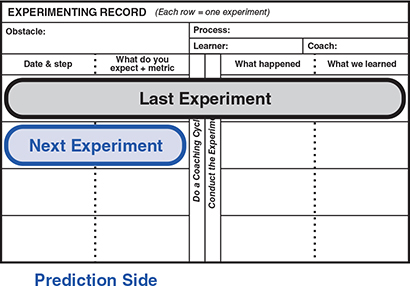

Reflecting on the learner’s last step is where learning comes from. What is learned from taking one step helps determine the next step (the next experiment). To reflect, the learner refers to the last filled-in row on their experimenting record, while you ask the four questions on the back of your card. Those four questions correlate to the four columns in the learner’s experimenting record:

Q1: What was your last step?

The learner points to and reads the description in column 1.

Q2: What did you expect?

The learner points to and reads their prediction in column 2, including how he or she proposed to measure the experiment.

Q3: What actually happened?

The learner points to and reads the resulting facts and data from the experiment, recorded in column 3, plus supporting documents such as new run charts. The learner should only refer to facts and data here, no interpretation yet.

Q4: What did you learn?

Before the coaching cycle, the learner has compared column 2 (expectation) and column 3 (resulting facts and data) and summarized what they learned in column 4. The learner now points to and reads the box in column 4. This is the place where the learner should make an interpretation of the results.

![]() Prediction error helps the learner find their way forward. Some of the best experiments have an unexpected result—a surprise—that helps the learner discover what will be necessary to reach the target condition. A target condition is reached through numerous small learning steps and experiments, many of which will generate “negative” (but highly useful) results.

Prediction error helps the learner find their way forward. Some of the best experiments have an unexpected result—a surprise—that helps the learner discover what will be necessary to reach the target condition. A target condition is reached through numerous small learning steps and experiments, many of which will generate “negative” (but highly useful) results.

Acknowledging and learning from prediction error can be difficult because it runs counter to our instincts. If the learner feels threatened by prediction errors they may start just laying on more countermeasures, rather than analyzing and learning from the situation.

Try to depersonalize the process of experimentation by emphasizing using experiments to learn. To function in this way your coaching cycle reflection should have a positive, we-are-detectives, no-blame feeling. To create that kind of depersonalized atmosphere, treat unexpected results not as good or bad, but simply as occurrences that can teach us something about the focus process and our improvement process. Of course, the learner should continue rapidly experimenting, in order to achieve the target condition by its set achieve-by date.

![]() The information in the four columns of the experimenting record should be written in by the learner before the coaching cycle. During the reflection portion of the coaching cycle the learner should respond to your questions by simply reading from their experimenting record.

The information in the four columns of the experimenting record should be written in by the learner before the coaching cycle. During the reflection portion of the coaching cycle the learner should respond to your questions by simply reading from their experimenting record.

![]() In column 2 the learner should have written down what they expect from a step before they took that step. (You checked this during the last coaching cycle.)

In column 2 the learner should have written down what they expect from a step before they took that step. (You checked this during the last coaching cycle.)

![]() In column 3 the learner should record only facts and data. No interpretation yet.

In column 3 the learner should record only facts and data. No interpretation yet.

![]() In column 4 the learner should record the conclusions they have drawn from the experiment. This might include new information about how the process is operating, better clarity on the nature or causes of obstacles, or even an “I don’t know” statement that better defines the threshold of knowledge. Column 4 is often the most difficult of the four reflection questions.

In column 4 the learner should record the conclusions they have drawn from the experiment. This might include new information about how the process is operating, better clarity on the nature or causes of obstacles, or even an “I don’t know” statement that better defines the threshold of knowledge. Column 4 is often the most difficult of the four reflection questions.

![]() Whenever necessary, have the learner adjust or correct what is written in the experimenting record immediately during the coaching cycle.

Whenever necessary, have the learner adjust or correct what is written in the experimenting record immediately during the coaching cycle.

![]() An experimenting record form should be dedicated to one obstacle. If the learner starts working on a different obstacle, they should use a new experimenting record.

An experimenting record form should be dedicated to one obstacle. If the learner starts working on a different obstacle, they should use a new experimenting record.

Q1: What was your last step?

“What was the threshold of knowledge?”

“What did you plan to do?”

“What was being tested?”

Q2: What did you expect?

“What did you think would happen?”

“What did you want to learn?”

Q3: What actually happened?

“Can you show me the data?”

“How do you know?”

“What does the data say?”

“What specifically did you observe?”

“Is there a run chart?”

Q4: What did you learn?

If a hypothesis was being tested, was it: “Confirmed” / “Refuted?” / “Can’t tell?”

“What was different than expected?”

“What do the data and your observations lead you to believe?”

“What are the implications for your next step?”

“Did you learn more about any obstacles?”

![]() The learner reports only verbally, without a completed experimenting record.

The learner reports only verbally, without a completed experimenting record.

![]() The learner mistakes a refuted prediction as a failure.

The learner mistakes a refuted prediction as a failure.

![]() Columns 3 and 4 have nearly identical entries. The learner fails to distinguish between what happened (facts and data only) and what they learned (interpretation).

Columns 3 and 4 have nearly identical entries. The learner fails to distinguish between what happened (facts and data only) and what they learned (interpretation).

![]() After conducting an experiment, a beginner learner continues to take more steps without first going through a coaching cycle.

After conducting an experiment, a beginner learner continues to take more steps without first going through a coaching cycle.

QUESTION 3

CURRENT OBSTACLE

Stay Focused

Turn to the front of your card and continue with the questions there.

Identifying obstacles means focusing in. Obstacles are what the learner experiments against as they strive for the target condition.

Have the learner answer the first part of question 3 by pointing at their obstacle parking lot (OPL) and quickly reading through all of the obstacles currently listed there. This represents the learner’s current impression about what the obstacles are. The second part of question 3, “Which *one* are you addressing now?” then usually defines the focus for the rest of this coaching cycle.

The learner should have updated the OPL before the coaching cycle, adding obstacles that have been discovered and crossing off obstacles that are no longer an issue. An arrow should indicate the one obstacle that’s currently being worked on. That obstacle should also be written on the learner’s experimenting record.

The obstacles parking lot is merely a place to record and hold perceived and encountered obstacles. It is not an action-item list, and the learner will usually not end up working on all the listed obstacles. This helps the learner realize how flawed initial perceptions and predictions can be, which is a key aspect of thinking scientifically. The OPL also helps the learner relax by acknowledging problems while keeping the learner from working on too many at once. The goal is to narrow down the scope of what the learner works on to reach the target condition, not to eliminate all potential obstacles.

Obstacles should be specific and measurable. If the target condition was vaguely stated, then the obstacles will probably be vague too. With a clearly defined target condition and a directly measurable process metric, obstacles should be easily recognized and measured.

Watch out for an obstacle recorded as a “lack of . . .” or a to-do item, which is incorrect. Lack of a countermeasure that the learner already has in mind is not an obstacle. “Lack of training” is not an obstacle, but “Some persons do the work incorrectly” is. When the learner’s description of an obstacle begins with words like “need to . . . ,” it suggests that the learner is already jumping to a solution.

![]() Obstacles are good to have because they tell you that you are on the move.

Obstacles are good to have because they tell you that you are on the move.

![]() The learner should generally work on one obstacle at a time, though there are exceptions.

The learner should generally work on one obstacle at a time, though there are exceptions.

![]() The learner is free to work on any obstacle. Don’t worry about starting with the biggest or most important one, especially if the learner is a beginner. Just have the learner pick one and get going. Working on one obstacle will often lead the learner to other obstacles, and in that manner the obstacles that need to be addressed will reveal themselves sooner or later.

The learner is free to work on any obstacle. Don’t worry about starting with the biggest or most important one, especially if the learner is a beginner. Just have the learner pick one and get going. Working on one obstacle will often lead the learner to other obstacles, and in that manner the obstacles that need to be addressed will reveal themselves sooner or later.

![]() It is perfectly legitimate for an obstacle to simply be something the learner needs to investigate, measure, and learn more about. This kind of obstacle might be noted on the OPL as, “We don’t yet understand . . . .”

It is perfectly legitimate for an obstacle to simply be something the learner needs to investigate, measure, and learn more about. This kind of obstacle might be noted on the OPL as, “We don’t yet understand . . . .”

![]() Action items and potential solutions are not the same as obstacles or problems. Here’s some Improvement Kata terminology: What the learner does to overcome an obstacle or problem on the way to the target condition is called steps or experiments. When the learner overcomes an obstacle, it means they’ve developed a solution to that problem.

Action items and potential solutions are not the same as obstacles or problems. Here’s some Improvement Kata terminology: What the learner does to overcome an obstacle or problem on the way to the target condition is called steps or experiments. When the learner overcomes an obstacle, it means they’ve developed a solution to that problem.

![]() It almost always takes more than one step to break through an obstacle, and often many more. The learner may work on one obstacle for some time, going through a series of experiments related to that obstacle. That’s normal.

It almost always takes more than one step to break through an obstacle, and often many more. The learner may work on one obstacle for some time, going through a series of experiments related to that obstacle. That’s normal.

![]() Sometimes the effort to overcome one obstacle also eliminates other obstacles or makes them irrelevant.

Sometimes the effort to overcome one obstacle also eliminates other obstacles or makes them irrelevant.

![]() Each experimenting record is normally dedicated to one obstacle. If the learner is switching to a different obstacle, they should start a new experimenting record.

Each experimenting record is normally dedicated to one obstacle. If the learner is switching to a different obstacle, they should start a new experimenting record.

![]() Sometimes it is OK for the learner to drop the focus on an obstacle and, instead, shift to another obstacle, based on something that has been learned.

Sometimes it is OK for the learner to drop the focus on an obstacle and, instead, shift to another obstacle, based on something that has been learned.

![]() Sometimes the learner will identify legitimate problems that may relate to the challenge, but not the next target condition. Start a separate list—off the storyboard—so the learner knows their concerns have been acknowledged and that they just aren’t working on those issues now.

Sometimes the learner will identify legitimate problems that may relate to the challenge, but not the next target condition. Start a separate list—off the storyboard—so the learner knows their concerns have been acknowledged and that they just aren’t working on those issues now.

“What exactly is the obstacle?”

“What exactly is the problem?”

“What problem does that obstacle cause?”

“How will you measure that?”

“Are there new obstacles you have identified?”

“Should any obstacles get crossed off the list?”

If lack of a perceived solution is being stated as an obstacle, ask: “What problem would that solve?” in order to get at the actual obstacle.

If only one obstacle is identified, you can ask, “If that one problem is addressed, will you be at the target condition?” Sometimes this leads the learner to more obstacles.

![]() The obstacles parking lot is treated as an action-item list.

The obstacles parking lot is treated as an action-item list.

![]() The obstacle is stated as a solution or to-do item.

The obstacle is stated as a solution or to-do item.

![]() The obstacle is too vague, not measurable. If the learner can’t be specific about an obstacle they may not understand the situation at the focus process enough or may be unaccustomed to being specific.

The obstacle is too vague, not measurable. If the learner can’t be specific about an obstacle they may not understand the situation at the focus process enough or may be unaccustomed to being specific.

![]() The obstacles parking lot is outdated—failure to cross off obstacles or add newly discovered obstacles.

The obstacles parking lot is outdated—failure to cross off obstacles or add newly discovered obstacles.

![]() The obstacles parking lot contains entries not connected to the target condition.

The obstacles parking lot contains entries not connected to the target condition.

QUESTION 4

PLANNING THE NEXT EXPERIMENT

The entire coaching cycle focuses down to this point, the threshold of knowledge and the learner’s next step.

Your task here is to ensure that the learner has planned a well-designed experiment to tell you what you need to know next, and, if not, to give corrective input. Remember, the plan for the next step is discussed in the coaching cycle, but the learner takes the step after the coaching cycle—ideally as soon as possible.

First have the learner tell you what they see as the current knowledge threshold. Ask, “What is the threshold of knowledge now?” or “What do we need to learn next?”

Then have the learner tell you, “This is what I intend to do next and why,” while you listen. Do this by having the learner simply read (and point to) their latest entries in columns 1 and 2 of their experimenting record. Based on learnings from the last step (discussed in the Reflection you just did) but before this coaching cycle, the learner should have written their proposed next step and a corresponding expectation on the left (prediction) side of their experimenting record.

Note that at question 4 you do want the learner to go beyond the threshold of knowledge and make a prediction. Here it is OK for the learner to say things like, “I think . . . ,” because in order to be scientific the learner must state in advance, and write down, what he or she predicts will be the result of the next step. Comparing the actual results with this prediction is where useful surprise and learning come from.

After the learner has read from columns 1 and 2 of the experimenting record, then you can go into more depth in your dialogue with the learner, about details and how they plan to carry out the next step, and so on. The coach should either accept the learner’s proposed next step (the next experiment) or give feedback to help improve the design of the next step. Use the “Coach’s Checklist for Planning the Next Experiment” in the following pages to help you either validate the learner’s proposed next step or get the learner to fine-tune their proposed step. If you think the learner needs to do more analysis and preparation before taking the next step, which is not unusual, then that should be the learner’s next step.

As you discuss the learner’s plan for the next experiment, you can have the learner immediately adjust or correct things that are written in column 1 and 2 of their experimenting record. You’re not changing data, you’re adjusting a plan. Or, if you like, you can opt to let the learner go forward with making a small mistake as a learning experience.

As soon as the next step (not a list of steps) is clear, the coaching cycle is near its end. There’s no need to try to look further ahead or for long discussion at this point. It’s time for the learner to take the next step as quickly as possible, so they can see further based on that.

![]() The coach and learner should have identified and discussed the current knowledge threshold before the next step is determined. The current knowledge threshold typically defines what will be the next experiment. This will often send you back to further investigate something you thought you already knew.

The coach and learner should have identified and discussed the current knowledge threshold before the next step is determined. The current knowledge threshold typically defines what will be the next experiment. This will often send you back to further investigate something you thought you already knew.

![]() Help the learner understand that any step they take is an experiment.

Help the learner understand that any step they take is an experiment.

![]() Get the learner to think about the desired result, not about something to be implemented. It helps to have the learner first state what they need to learn, and then describe their plan for learning it.

Get the learner to think about the desired result, not about something to be implemented. It helps to have the learner first state what they need to learn, and then describe their plan for learning it.

![]() Designing and conducting the next experiment toward the target condition is a great place for the learner to involve other persons in the focus process and get their ideas.

Designing and conducting the next experiment toward the target condition is a great place for the learner to involve other persons in the focus process and get their ideas.

![]() The learner should set up experiments so that mistakes and unexpected results will not create an unsafe condition or harm the customer process. (Sometimes this is humorously referred to as limiting the blast radius.)

The learner should set up experiments so that mistakes and unexpected results will not create an unsafe condition or harm the customer process. (Sometimes this is humorously referred to as limiting the blast radius.)

![]() If the next step can be taken right away, then by all means do that. How about right after this coaching cycle?

If the next step can be taken right away, then by all means do that. How about right after this coaching cycle?

![]() Experiments do not have to be big or long, even though we may think that. Asking the learner, “What can we learn today?” can help to narrow the scope.

Experiments do not have to be big or long, even though we may think that. Asking the learner, “What can we learn today?” can help to narrow the scope.

At the beginning learners will often try to make the next step bigger than it needs to be, which can overshoot the knowledge threshold and hamper learning. Guide the learner into experiments that are as small and as rapid as possible for the situation. You’re not looking for big leaps. You’re looking for a good experiment. Caution: if your coaching cycles are not daily, the learner’s steps may tend to get too big, because the learner will naturally want to do lots of things before you finally meet again.

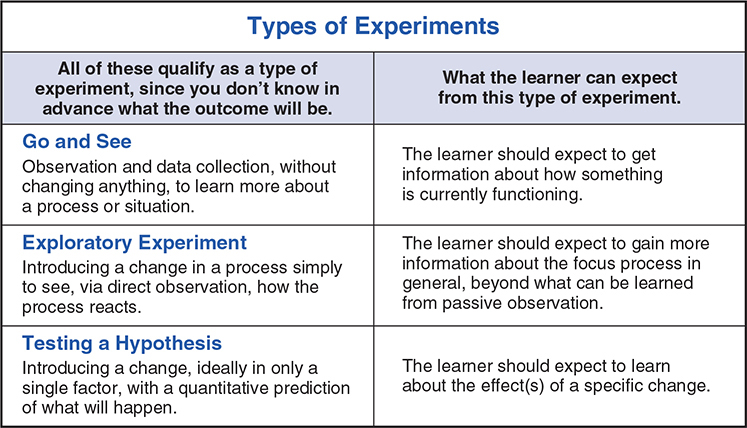

![]() “Go and get more information” can be a next step. That’s normal. There are different kinds of experiments, as described in the following table.

“Go and get more information” can be a next step. That’s normal. There are different kinds of experiments, as described in the following table.

1. About the threshold of knowledge:

“What is the threshold of knowledge now?”

“What do we need to learn next?”

2. About the design of the next experiment:

“How will the test be done?”

“How will you measure it?”

“How will you collect the data?”

“What is the process metric?”

“How many data points do you want?”

“What is the outcome metric?”

“What happens if the outcome is not as expected?”

“Can you test this today?

“Could we test it right now?”

“What can we learn today?”

3. About the learner’s prediction—you can ask two slightly different questions here:

“What do you expect to happen?”

“What do you expect to learn?”

Other questions are:

“What do you want to happen?”

“How will you know?”

![]() Failure to identify the current threshold of knowledge before designing the next experiment.

Failure to identify the current threshold of knowledge before designing the next experiment.

![]() Definition of the next step is too vague (and thus an equally vague “What do you expect?”).

Definition of the next step is too vague (and thus an equally vague “What do you expect?”).

![]() Coach doesn’t ask the learner how they will measure the effect of an experiment.

Coach doesn’t ask the learner how they will measure the effect of an experiment.

![]() Coach fails to have the learner write down the details of the next experiment, including what the learner expects to happen and to learn.

Coach fails to have the learner write down the details of the next experiment, including what the learner expects to happen and to learn.

![]() Instead of stating an expectation, the learner just restates the next step in past tense.

Instead of stating an expectation, the learner just restates the next step in past tense.

![]() Next step is an action item, not an experiment. Learner wants to implement an idea without testing it.

Next step is an action item, not an experiment. Learner wants to implement an idea without testing it.

![]() Learner overlooks “Go and see” as a legitimate experiment.

Learner overlooks “Go and see” as a legitimate experiment.

![]() The experiment is too risky.

The experiment is too risky.

![]() The next step is too large.

The next step is too large.

QUESTION 5

PREPARING FOR THE NEXT COACHING CYCLE

With question 5 you are looking for a fast turnaround. The purpose here is to get the learner to do the next experiment as quickly as possible, because both of you can’t see further toward the target condition until that happens.

When the learner’s next step is clear and written on the experimenting record, a coaching cycle is essentially done. All that’s left is confirming the time for the next coaching cycle. There is no need to discuss further, because both coach and learner are at the current knowledge threshold at least until they get the results from the next experiment.

The next coaching cycle will often be the next regularly scheduled one, but you can also add a coaching cycle any time you would like. For example, to give a beginner learner closer coaching and less chance to acquire poor habits, you can schedule a coaching cycle for right after the learner has taken their next step. Sometimes you may even decide to accompany or check in on the learner as they carry out their next step.

Having only a single action item may feel uncomfortable if you are accustomed to full action-item lists. You may soon discover, however, that experimenting every day is faster and more effective than trying to lay out the exact path of steps in advance.

And you’re done

![]() Question 5 can be tricky. New coaches and learners often incorrectly think it means, “When will you have it done?” but question 5 is more about seeing, “What are we learning?” Caution! Even when you ask question 5 with the correct intention, the learner may still actually be hearing you say, “When will you have it done?”

Question 5 can be tricky. New coaches and learners often incorrectly think it means, “When will you have it done?” but question 5 is more about seeing, “What are we learning?” Caution! Even when you ask question 5 with the correct intention, the learner may still actually be hearing you say, “When will you have it done?”

![]() Agree on a specific date and time for the next coaching cycle.

Agree on a specific date and time for the next coaching cycle.

![]() Agree on what data and information the learner should obtain, prepare, and have recorded on their storyboard before the next coaching cycle.

Agree on what data and information the learner should obtain, prepare, and have recorded on their storyboard before the next coaching cycle.

![]() The first response to, “When can we see?” is often something like, “Next week.” Challenge this! If necessary, accompany the learner to show him or her how to experiment cheaply and quickly, to get new information and see further as swiftly as possible. How to run rapid experiments is one of the skills you are teaching.

The first response to, “When can we see?” is often something like, “Next week.” Challenge this! If necessary, accompany the learner to show him or her how to experiment cheaply and quickly, to get new information and see further as swiftly as possible. How to run rapid experiments is one of the skills you are teaching.

“How could we do this experiment sooner?”

“How could we do this experiment today?”

“How about we do the experiment right now, together?”

![]() A common error is having a task orientation instead of a learning orientation. For example, if the coach incorrectly asks, “When can we go see what has been accomplished?” rather than, “When can we go see what we have learned from taking that step?”

A common error is having a task orientation instead of a learning orientation. For example, if the coach incorrectly asks, “When can we go see what has been accomplished?” rather than, “When can we go see what we have learned from taking that step?”

![]() Coach and learner keep on discussing even though the coaching cycle should now end, for instance speculating about what will happen with the next step. A coaching cycle should stay focused on the next step and then stop.

Coach and learner keep on discussing even though the coaching cycle should now end, for instance speculating about what will happen with the next step. A coaching cycle should stay focused on the next step and then stop.

![]() The next coaching cycle is too far in the future. Coaching cycles are too infrequent, resulting in more than one step getting discussed in the coaching cycle.

The next coaching cycle is too far in the future. Coaching cycles are too infrequent, resulting in more than one step getting discussed in the coaching cycle.

![]() No specific date and time are agreed upon for the next coaching cycle before ending this coaching cycle.

No specific date and time are agreed upon for the next coaching cycle before ending this coaching cycle.

SUMMARY

Coaching cycles will seem stiff and awkward at first, for both the coach and the learner. In time the format will flesh out with your own clarifying questions and style, and a certain, “Wow, look at the obstacles we are overcoming!” dynamic should appear. That’s when energy and self-efficacy are created.

Practice Protocol:

What the Learner Should Do During a Coaching Cycle

On the Achieve-by Date the Four-Step Improvement Kata Pattern Repeats

When the learner reaches their target condition or its achieve-by date, the four-step Improvement Kata pattern repeats. However, before that the coach and learner should do a summary reflection over the entire process. This can lead to learnings that can be applied in the next cycle through the four steps of the Improvement Kata pattern. See the short “Summary Reflection” chapter at the end of Part II. Have the learner reflect on how they worked by asking questions such as:

“Why are we using the Improvement Kata pattern?”

“What did we gain by doing that?”

“What went well?”

“What could be better?”

“What aspects of the Improvement Kata should we work on next time?”

1 The original version of this coaching cycle was written by Tilo Schwarz (www.lernzone.com) and published in Yokoten magazine, Issue 5, 2016 (www.yokoten.de).