Chapter 4

![]()

Developing Lean Processes: A Short Story

Conventional project management attempts to define what to do and when by defining a detailed plan and trying to stick to it. . . . This almost never works. Lean companies create a web of small, constantly operating, rapid, cadenced cycles.

—Allen Ward and Durward Sobek, Lean Product and Process Development

HOW DO WE CREATE LEAN PROCESSES?

Efficiently flow high value to customers and get it right every time. Can anything be more simple? Do this, and you have lean processes, your customers will love you, and your competitors will be quaking in their boots. Of course, it is anything but simple. It seems simple when we tour a Toyota assembly plant and vehicles are flowing down the line, one by one, and exiting at one a minute. One-minute jobs seem simple. However, zoom out, and we see tens of thousands of parts flowing through a complex network of suppliers and departments with tens of thousands of opportunities for something to go wrong. Making everything work perfectly on time every time seems overwhelming, but what most people miss is that Toyota is not trying to optimize a complex value stream. What it is doing is working to ensure that all production team members can accomplish their 60-second tasks with perfection, and when anything goes awry, group leaders and team leaders react instantly, stopping production if there is any real threat to safety or quality. Thousands of small loops of PDCA are locally managed every hour of every day throughout the value chain.

This is not the case in most companies, in which the mechanistic mindset we talked about in Chapter 3 pervades process improvement efforts. Senior leaders want their processes fixed to reduce cost and stop customer complaints. To accomplish this, processes are reengineered, constraints found and protected, and variation statistically analyzed, in efforts to optimize processes so “everybody does it the same way.” Mostly these efforts start with one appealing, but terribly flawed, assumption: processes are seen as real things that can be bent, twisted, leaned out, and shaped to streamline the flow of value to customers, like cutting and bending pipes to flow water.

In reality processes are theoretical constructs—metaphors. Consider the work of many engineers producing the design of a product or piece of software in most companies. Like any work undertaken with a traditional project plan, it looks like distinct stages with certain deliverables at gates in between. The engineers develop a concept that they test with the customer, do detailed design, verify the product, and work with manufacturing to launch into production. But it is not nearly this orderly if we watch what happens. A lot of people are meeting, thinking at various times, writing things down, and using computers, and at key points management checks in on progress. It is messy and nonlinear. There are rework cycles, target dates slip, and somehow at the end the product or software is produced, to be tested in the market. Shaping the patterns of work to ensure a semblance of flow, regular checking in short cycles, ongoing customer feedback, deliberate improvement, clear deliverables, and accountability has more to do with shaping how people think and work than the unrealistic image of “optimizing a process.”

When we work with companies on improvement, we never walk in with a prepackaged set of solutions or a 10-step model for leaning out the organization. We do, however, have at a high level a generic approach to process improvement, and simultaneously to people development, that consists of the following steps:

1. Be sure that senior leadership is serious about need for change. The starting point, of course, is the need for change. Someone in a position of authority must believe there is a reason to change. We often say you need a burning platform, and that seems true more often than not. But from time to time we are pleased to find a senior leader with a positive vision to get better even when all seems to be going well.

2. Understand senior leadership vision. What is the senior leaders’ strategy to achieve business objectives? What do they value as an organization? What is their vision for lean, and how does it fit into their objectives and values? This often involves some work with senior leaders to get them thinking about their vision for the company, its processes, and its people.

3. Grasp the situation. What is going on in the company, its culture, and its business priorities? How is the company performing? Are senior leaders’ values actually visible in action? On what major business challenge should our initial attention on improvement be focused? How can we get senior management on board to learn from the experiments that will be conducted? Where should we begin to focus and with what team(s)?

4. Understand the current state. In relation to the main business challenge, what is the current state of the work processes? Where is the leverage to make an immediate impact to move in the direction of the key business challenge? Who are the key people who need to get on board?

5. Identify gaps and prioritize. How can the big gap between the current state and desired future state be broken into smaller, manageable chunks of work to assign to people so that they can get started working toward improvement right away?

6. Strive for the future state through small cycles of learning. This is where PDCA is practiced, step by step, to work toward the future state—that is, planning an improvement (Plan), testing it (Do), checking what happened (Check), and reflecting on what was learned and what further actions should be taken (Act). This iterative process both moves the work toward the future state and develops in people positive habits for improvement.

We have organized the process layer of the Toyota Way as a set of three chapters that may seem to be in reverse order. We often think about learning principles—or a model of the right way to do something—and then illustrating the principles with examples and how-to tips. Instead, in this chapter we will start with how to approach process improvement, illustrated by a composite case, and then in Chapters 5 and 6 build on the case to define principles of macro-lean and micro-lean processes in service organizations. By macroprocesses we mean the big picture as one would depict in a value-stream map. Microprocesses are the daily work at the level of a department or work group, as is illustrated in this chapter. The composite case was developed by Karyn based on her 10 years of experience in large service organizations. It is an artificial company, but she can relate all the details of what happens to actual experiences. Let’s dive into the case of NL (Not Lean) Services, Inc.

In this story a credit transaction company is in deep trouble. It is not growing, and in fact unhappy customers are leaving. The crisis is enough to push a vice president, Sam McQuinn, to seek help from a trusted friend who points him toward her lean consultant, Leslie. Fortunately for Sam, Leslie is a rare consultant who knows how to engage people and push and prod in just the right ways. As you read the story, notice the tight integration of process, people, and problem solving. This is a key point and a far cry from the common view that processes are like mechanical entities that can be improved by simply applying the right lean tool. Let’s look in on NL Services.

THE NEED FOR CHANGE AT NL SERVICES, INC.

A Day in the Life of NL Services

It was a typical Monday morning at NL Services, Inc., an American company with 13,000 employees in 95 offices that processed credit transactions for companies that accepted credit payments. John Edwards, manager of Credit Transaction Processing for the Southern Region, presided over his weekly staff meeting. His six managers oversaw teams that handled credit transactions. As per the standard agenda, John went slide by slide through a PowerPoint of the previous week’s data sent by the company’s corporate office.

“Doesn’t look any better this week,” John said sternly, using his laser pointer to highlight a plethora of graphs and charts. Not a single team in the Southern Region was even close to the targets that corporate had given for new business growth, client retention, customer satisfaction, or profit. “Corporate really doesn’t like any of these numbers. I had a very unpleasant conversation with our VP this morning. His perspective is that ‘the number is the number’ and that he doesn’t care how we, or our people, make those numbers, but he better see some marked improvement in the next couple of weeks, or else. By the end of the business day I need a plan from each of you for how you will make your numbers.”

The six CTPMs (credit transaction processing managers) stared alternately at the PowerPoint, at John, and around the room at each other. Some crossed their arms tensely, leaning forward in their chairs. Others just looked bored and resigned. They’d all been through this before. Every few months, when the numbers dipped down for a few weeks in a row, they heard the same speech. And every few months, after they offered the credit transaction processors some incentives, like pizza parties or jeans days, and also threatened possible layoffs and other dire consequences, the numbers came back up. They knew they would make it through this time too.

Meanwhile, back in operations, Kathy, one of a team of 12 credit transaction processors had just hung up the phone. It was only 9 a.m., and her ears already hurt from listening to an angry customer complaining about how his bill was wrong . . . again. After spending 20 minutes on the phone going through all the records with the customer, Kathy was able to correct the error, but now she needed her manager’s signature on the Billing Correction form to credit the customer’s account and give him the discount that she had promised him for his trouble. It seemed to Kathy that she was always giving customers discounts. The credit processors had to fix so many errors that it seemed to be the only way to keep customers happy and to stop them from changing to another credit processing service.

As Kathy looked around for Joe, her manager, she remembered that it was Monday morning and that he would be, like he always was on Monday mornings at 9 a.m., in the weekly staff meeting. “Customers are just going to have to wait,” Kathy thought to herself. “Mondays are always like this. And it doesn’t look like the week’s going to get any better. I already have a backlog of 25 credit transactions that just seem to have popped into the system over the weekend, and one of the credit transaction processing systems is down, so anything that needs to be input into that system is going to have to wait. You wouldn’t think that credit transaction processing would be this hard. But with having credit transactions come in by e-mail, fax, and phone calls, needing to use four different credit transaction processing systems that don’t talk to each other, and having to wait for answers about transactions from so many different departments, it’s not as easy as it looks. And stopping to fix billing problems for angry customers doesn’t make it any easier, that’s for sure.”

Looking around one more time to see if Joe might be on his way back from the staff meeting, Kathy dropped the Billing Correction form on Joe’s desk and headed back to her cubicle. As Kathy sat down, Linda, the credit transaction processor who sat beside her, looked up from the pile of paper transactions that she had printed and was going to input and asked, “Everything okay? Smile, it’s Monday! The fun’s just beginning!”

“Right!” said Kathy. “Another week, but the same old problems. Customers already unhappy, and I’m sure this isn’t the only billing correction I’ll be processing this week. Every time we enter transactions involving more than 10 line items, this problem seems to happen. I’ve told Joe about it a number of times, but he tells me I’m just imagining it, so I’ve given up trying to talk to him about it, and I guess we’ll just fix the problems when they happen. Anyhow, I’m already way behind, so I’d love to chat more, but I better get back to work.”

Finally, around 10:30 a.m., John’s weekly staff meeting wrapped up. The CTPMs headed back to their teams, armed with an incentive plan offering a free dinner and jeans days for a month to all credit transaction processors who would be willing to work overtime for the next two weeks to catch up on backlogs and make extra calls to customers. The program was “voluntary,” but the credit transaction processors understood that those who didn’t participate might be the first to go if there was another round of layoffs. The CTPMs were confident that in a couple of weeks, with all the extra focus and work, their numbers would be fine and that John, and corporate, would be off their backs . . . until the next time.

After announcing the program to his team, Joe headed back to his desk, signed the Billing Correction form, and gave it back to Kathy. Kathy called the customer back and gave him an extra discount for having to wait so long for her response.

All fires out for now.

Reflection: The Troubling State of NL Services

Obviously all fires are not out. John just can’t see them festering throughout his organization. In The Toyota Way Fieldbook we talked about the concept of “clearing the clouds.” When the normal state is chaos, it is difficult to even see the processes. They seem hidden by clouds. There are in fact existing work patterns, but you need to clear the clouds to see them. We see that some standard practices are responding to problems by giving little bribes to customers for their troubles. We see that Kathy is spending much of her time reacting to customer complaints, which prevents her from getting the work right the first time. Lingering problems, like transactions that come in with more than 10 lines, are avoided, not solved. Kathy does not feel any support from her boss, but she regularly works around her boss’s busy schedule of doing who knows what.

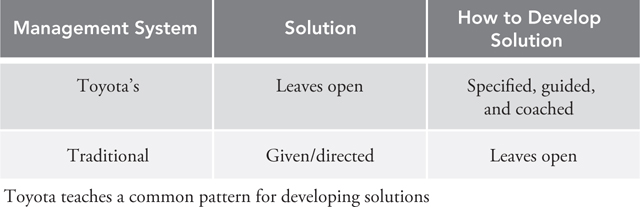

The culture is one of going for results at all costs and fighting daily problems. Figure 4.1 compares the problem-solving culture of traditional versus lean organizations. In traditional organizations management specifies solutions and results and does not particularly care how frontline managers put the solutions into practice as long as they get results. This is a target-rich environment for lean intervention, but the people in the organization seem unable to see how they can get out of the vicious cycles that entrap them. The Toyota system is more concerned with team member development to learn a good process for improvement. The specific solution is less important than following a good process.

Figure 4.1 Process improvement approach for lean versus traditional management system

Source: Mike Rother

Reaching Out for Help

Sam McQuinn, one of NL Services’ vice presidents of Credit Transaction Processing, checked his watch again. “Already 6:30 p.m. . . . how can that be?” he thought to himself. “Don’t know where this Monday has gone, but I certainly can’t say it’s flown by because I’m having fun.”

Truth is, Sam wasn’t having fun. Between conversations with corporate office people on the East Coast and the four regional managers that reported to him, Sam hadn’t gotten off the phone since he arrived in the office at seven that morning. And none of the conversations had been pleasant. For the third week in a row, none of the regions that he was responsible for had hit their numbers—the third time this year—and corporate was breathing down his neck hard.

“Don’t know what’s wrong with those regional managers,” Sam muttered. “I keep telling them that this isn’t acceptable, but they just don’t seem to get it. No matter how many times I make it clear that they need to get their acts together, things only improve for a little while, and then I’m back on the phone, threatening and cajoling again. We can’t keep going on like this; something’s got to give.”

Shutting down his computer, Sam checked his watch again. If he left right now and there wasn’t too much traffic, he should be right on time for dinner and drinks with his friend and former colleague, Sarah Stevens. Sam and Sarah had worked together at NL Services for more years than Sam cared to count before Sarah had moved over to take a higher position at a smaller company that was just starting out. Sam was looking forward to both commiserating with Sarah and asking for her advice. She’d know just how he felt—and she had a knack for solving problems in unusual ways too.

When Sam arrived at the restaurant, Sarah was already seated, poring over the menu. As Sam sat down, Sarah looked up and said, “Must have been a typical Monday at NL Services. You look totally beat up!”

Slipping his cell phone into his pocket so that he could avoid the inevitable phone calls and e-mails from corporate that he knew would keep coming, Sam answered, “Yeh. Regional numbers are down again—for the third time this year. Between dealing with corporate and the regional managers, I haven’t had a break all day. Just when I think the regional managers have things under control and are making their numbers, everything falls apart again. No matter how much I threaten or promise, they just can’t seem to get their people in line and hit their targets. I just don’t know why it’s so hard . . . it’s not like we haven’t known what the numbers are since the beginning of the year. I’m at the end of my rope.”

Frowning slightly, Sarah shook her head and sighed. She knew what Sam was going through. It was one of the reasons that she had left NL Services. She was tired of feeling beat up every time her region’s numbers weren’t where they were supposed to be. “I know how you feel, Sam,” Sarah said. “One of the things that I’m enjoying most about my new job is getting off that roller-coaster ride. Although I was skeptical at first, the consultant that we hired to help us is really making a difference. Her name is Leslie, and she is a lean management advisor. You’ve heard of lean management made famous by Toyota, right? Well, I thought that all that lean stuff was just for manufacturing organizations . . . after all, neither my company nor NL Services makes widgets, but it’s been about a year now, and for the most part, I’ve stopped having the kind of Mondays that I was used to at NL Services—and that you’re having today. If you’d like, I can give you her card and let her know you might call. I will warn you that Leslie really is an advisor and facilitator, but you and your people have to do the hard work—she will not do it for you. Her philosophy is that you need to develop the capability to improve your own people and processes.”

Reflection: Reaching Out for Help

There is an old Buddhist expression, “When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.” Sam did not realize he was ready for a teacher, but he sought support from a trusted peer. Sarah had walked in his shoes in his current company and left because of the very types of daily crises that Sam was still living. She had learned a better way at her new job. She listened empathetically and made a suggestion, with no pressure and no self-interest. As we will see, Sam was willing to take Sarah’s advice because it was the right time and he trusted Sarah.

UNDERSTANDING AND ENCOURAGING LEADERSHIP VISION

Leslie Meets Sam and Asks for His Vision

Two weeks later, Leslie Harris, the lean consultant that Sarah had recommended, was sitting in Sam McQuinn’s office waiting for Sam to finish up a call. As she looked around the room, she noticed the picture hanging on the wall behind Sam’s desk: a sculling boat with all the oars in the water. “Interesting,” she thought to herself.

After the introductions and required pleasantries, Sam got straight to the point: “I’m not usually one to ask for help, and I’m not totally convinced that this lean stuff can work here at NL Services since we do not manufacture any physical products, but Sarah Stevens said that you really helped her company. To be honest, I am desperate and willing to listen to what you think you can do for us here. The problem is actually quite simple. The credit transaction processors aren’t doing what they’re supposed to be doing, so we’re not meeting the numbers that our corporate office has set for us on a regular basis. We need to find a way to get the credit transaction processors and their managers and the regional managers all under control so that we can get those numbers back to where they should be once and for all. If Sarah thinks that you’re the person that can get that done for us, I’m willing to give you a chance.”

Leslie thought for a moment before she replied. “Sam,” she said, “I’m happy that Sarah thinks so highly of the outcomes at her company that she would recommend me. Her company thought the problems were simple in the beginning too, and that it would be a quick and easy fix, but it has been a lot of hard work to get where we are today. Before we start ‘fixing’ problems and putting solutions into place here at NL Services, we’re going to have to spend some time really understanding what’s going on in credit transaction processing and what your vision is for the organization. This may sound strange given your immediate problems, but it is important that your direction is clear before we start randomly fixing things. Sam, I know you have heard this before, but it all starts with the customers. What can we do to make their lives better, and how are we doing against that vision?”

Leslie paused a minute to give Sam time to think about what she had just said. Then she went on, “It’s like that picture of the boat with the oars in the water that you have hanging behind your desk. When all your processors, managers, and regional managers are working together toward the vision that you have of how to deliver value to your customers, the boat is going to be going in a straight line in the water! Instead of thinking about ‘making our numbers,’ we need to understand how NL Services’ credit transaction processing is going to deliver that value. So Sam, what is it that your customers value, and what is your vision for delivering that value?” Folding her hands in her lap, Leslie sat back in her chair and waited quietly for Sam’s response.

Sam didn’t say anything for a couple of minutes. Each time he started to speak, he paused again. Leslie seemed different from other consultants he had hired. They all wanted to make a good first impression by providing their brilliant solutions right away, not by asking a set of questions . . . questions that he had to admit to himself he was not sure how to answer. Reflecting, Sam realized that he hadn’t really thought about NL Services’ customers in years—or what they might value. He was focused on “making the numbers” and getting corporate off his back. And a vision of how to deliver that value? Sam was pretty sure he’d need some help figuring that one out. But Leslie came highly recommended by Sarah, and Sarah’s company was doing better than most of the competition, even though the company was pretty new. Sam turned and looked at the picture behind his desk and then turned to Leslie. “Leslie,” he said, “I’m not sure that I know how to answer your questions, but if you’re willing to work with me to figure this out, I would like to invite you to help us at NL Services, Inc.”

Understanding Leadership Vision

Despite his friend Sarah’s warning, Sam immediately looked to Leslie for solutions. She would not allow herself to be baited by Sam into jumping into his idea of what the problems were and offering solutions. If she did that, she would be violating the very principles she was trying to teach her clients. Instead she deflected the conversation by asking Sam what his vision was for his organization. This caught Sam off guard and made him think. He was not used to consultants making him think. He was used to consultants giving him what they thought he wanted to hear so that they could win his business.

In this case, Sam is acting like the ideal learner and quickly concludes he has not spent enough time establishing a vision for customer service. This short interaction convinces him he wants to work with Leslie. Obviously life is not always so easy, and many managers in his situation would push back at Leslie, looking for answers. “If I wanted questions, I would not need a consultant.” In such cases it may be that the student really is not ready for the teacher. As it is, Sam will begin to develop a vision. It will not be an elaborate vision, and Leslie is not using a structured process to develop a strong vision. At this point that would be too much for Sam. She has to meet him where he is, which is just starting the process of reconsidering his basic assumptions of how to lead.

Notice that Sam did not immediately establish a committee to find the right consultant based on competitive bids. Often large corporations have a standard practice of competitive bidding, and a committee issues a request for bid. The usual suspect consulting firms write elaborate proposals promising the world, often without knowing much about the company and its situation. They propose generic solutions to generic problems. As we get to know Leslie, we can safely bet she would not have been willing to play the competitive bidding game. By engaging Leslie from the start, based on his gut feeling, Sam is giving Leslie an opportunity to follow an organic process of coaching him, drawing out of him his vision, and grasping the situation to learn how to proceed rather than walking in with a detailed proposal and off-the-shelf solutions.

GRASPING THE SITUATION

Getting to Know the Organization, Culture, and Issues

It was a beautiful sunny morning, clear skies with just a few clouds drifting by, as Leslie Harris pulled into the parking lot of the NL Services’ Southern Region building. As she walked across the parking lot, Leslie thought about how much she was looking forward to this, her first visit to see NL Services’ operations. Although it had taken quite a few lengthy discussions, she and Sam McQuinn had finally determined that what NL Services’ customers valued was credit transactions processed accurately within each state’s regulations for timing. Because the acceptance, processing and reporting on these types of payments was heavily regulated, this prevented the customers from having to pay the fines the states imposed for late payments and reporting and stopped them from having to deal with the resulting stress.

After signing in, Leslie made her way to the third floor, where she found John Edwards, the Southern Region’s manager of Credit Transaction Processing, sitting in his office, memo in hand, waiting for her.

“Leslie, nice to meet you,” John said, extending his hand. “You seem to have made quite an impression on Sam. He’s sent out a number of memos—just like this one—talking about things like focusing on what our customers value and the vision that he has for our region’s credit transaction processing: ‘Every customer’s credit transaction right and on time, every time.’ Sam said that you’re going to spend some time with us today taking a look at our operation. I’m sure that you’ll find everything is in order.”

Leslie smiled. She shook John’s hand and said, “John, I know you’re going to find this hard to believe, but I’m not here to review your operation to report on whether things are ‘in or out of order.’ I’m simply here to spend time with the people who process the credit transactions for your customers to learn about how they do their work each day. And the best way for me to learn about how they do their work is to spend time with them as they do that work. I’m really looking forward to that—it’s one of my favorite parts of what I do!”

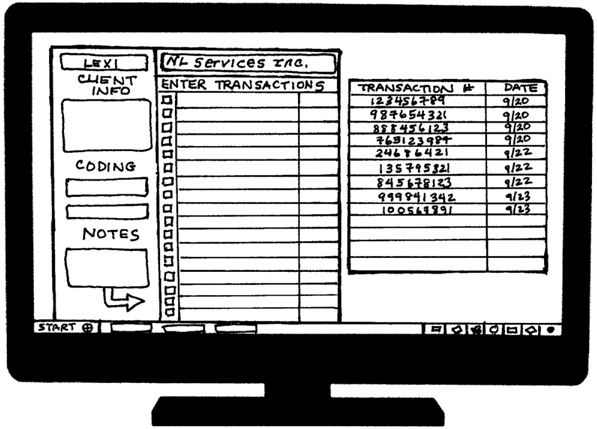

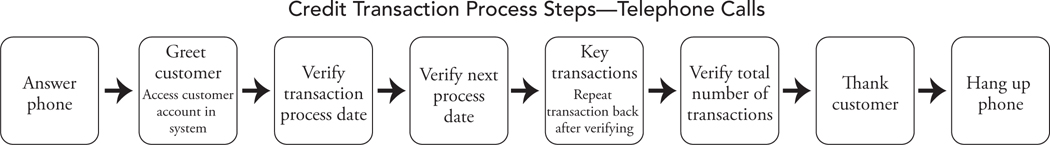

John and Leslie walked downstairs to the first floor, where three teams of credit transaction processers sat. John explained to Leslie that the credit transaction processors primarily answered phone calls from business customers who accept credit cards. The customers accumulate a set of transactions and then either call them in by phone, send them electronically through the Internet, or mail in credit card receipts. Most of these businesses call in to report the transactions or send e-mails. If the credit card was read electronically, as at a gas station, then a report is generated via e-mail to the credit card agency. Unfortunately the computer systems do not communicate well with each other and even in the electronic case have to be manually reentered into NL Services’ computers. In most cases there are fewer than 10 transactions at a time from one customer. Less often, the processors enter credit information with more than 10 transactions, which customers send by Excel spreadsheet attached to an e-mail or fax. The processors spend a small percentage of time fixing errors on completed transactions and handling billing questions.

As John and Leslie looked across the rows of cubicles, John asked, “Where would you like to start?”

Leslie answered, “If you could introduce me to a manager of one of the teams, that would be great.”

John led Leslie around the corner, where they found Joe, one of the CTPMs, reviewing an Excel spreadsheet on his laptop’s screen. “Joe, I would like you to meet Leslie Harris,” John said. “I know you’ve seen some of the memos that Sam has been sending from the regional office. Leslie’s going to spend the day reviewing how we process our credit transactions, so please do whatever you can to help her out.”

“Nice to meet you, Leslie,” said Joe. “Would you like to pull up a chair? I’m just going over the ‘daily report’—tells us how we’re doing on our credit transaction processing. What’s on time, what’s not. How many calls we took yesterday. How we’re doing making our numbers . . . all that good stuff . . . it’ll give you a really good look at what we do and how we do it.”

Leslie pulled up a chair and sat down next to Joe. “Thanks for offering to walk me through your report. I’m sure it has a lot of data, but what I’d really like to do first is . . .” But before Leslie had a chance to finish her sentence, there was a tap on the cubicle wall.

She and Joe looked up to see one of Joe’s team members, Kathy, looking agitated and holding out a piece of paper. Before Joe could say anything, Kathy said, “Look, another Billing Correction form for you to sign. And it’s for the same customer that I had to give that big discount to last month. He’s so angry he wants to leave NL Services and switch to our competitor. Every time there are 10 or more credit transactions on the spreadsheet in his e-mail, there’s always an error. I know you think it’s just my imagination, but this keeps happening, and now we might lose a big customer.”

Joe, looking a little sheepish, said, “Kathy, let me sign the Billing Correction form, and then I’ll give the customer a call and see what I can do. And by the way, this is Leslie; she’s here to learn about NL Services’ credit transaction processing process.”

Leslie reached out and shook Kathy’s hand. “Nice to meet you, Kathy,” she said. “Seems like you’ve identified a problem in the credit transaction processing process. I’d love to hear all about it. If you have a few minutes, Joe and I can come over to your desk and take a look and see what happens when you process transactions with 10 or more credits.”

Leslie and Joe spent the next two hours together watching how his team of credit transaction processors worked. As they sat together watching and listening, they saw how hard it was for his team members to process transactions with more than 10 credits. And they heard how unhappy the errors on those transactions made customers. Even worse than billing problems, quite a number of them had fines from the states to deal with as well.

Just before lunch, Joe and Leslie headed back to Joe’s cubicle. “Joe, do you have any idea approximately how many errors are occurring because of the problem of processing 10 or more credit transactions at one time?”

Looking a little worried, Joe replied, “Actually, Leslie, it’s a lot more than you might think. I know it’s not good for our customers and it’s hard on my people, but there’s just nothing we can do about it. And if I bring it up in the management meeting, all I hear is ‘no excuses, just make those numbers.’ I wish I knew what else I could do . . .”

“Joe,” said Leslie, “don’t worry. I have an idea—an idea that I think will be able to help Kathy, you, and NL Services’ customers too.”

Reflection: Getting to Know the Organization, Culture, and Issues

Sam’s direct reports are getting the news that Sam is excited about the new consultant and is on board. Sam has even developed a simple but powerful vision statement, and it is focused on service quality from the customer’s perspective. Now we have the beginning of a direction for improvement.

Leslie did not have a fixed agenda on her first day at the gemba. She was watching and waiting for the right opportunities to understand what was really going on. On cue as John was explaining things, Kathy walked in, and Leslie saw a golden opportunity for a quick win solving the 10-line problem. It was clear that simply sitting with John and listening to him go over reports and expound on what he thought the key issues were was not going to give her a picture of the current condition. They needed to go to the gemba. And encouraging Joe to go to the gemba with her was an opportunity to do some coaching.

Narrowing the Problem Space and Establishing the Team

Sam McQuinn was pacing back and forth in his office. It was Wednesday afternoon just after lunch: 12:45 to be exact, and he had a one o’clock meeting with Leslie. “What could possibly be taking her so long?” Sam wondered. He’d spent his whole morning on the telephone again. He’d had to field calls from angry executive VPs, calls from the corporate quality department, and, worst of all, calls from corporate audit. Next there was the required round of calls to all the regional managers. “What could be so hard about getting to those numbers? Especially the client retention numbers. What could they possibly be doing down there in operations that was causing so many customers to leave?” Sam fumed. “And where is Leslie?” he thought to himself again. “Leslie should know how to get to the bottom of this. She’s certainly spent enough time with the credit transaction processors to have figured out what the problem is—and what can be done about it—not next year, but right now.” Just as Sam was about to pick up the phone again, Leslie, calm and cheerful as always, rounded the corner into his office.

“Sam, how are you today? Good to see you again,” said Leslie. “I’ve really learned a lot about your business since the last time we met, and I’m looking forward to sharing that with you today.”

“Leslie,” said Sam, “that’s exactly what I was hoping to hear. I’ve spent the whole morning on the phone with corporate, and it seems that the credit transaction problems have gotten so bad that we’ve just lost our biggest customer. That’s a huge hit to the Southern Region’s retention numbers, and it’s going to have a huge impact on our revenue. And if that isn’t enough, the fines the customer got from the state are so huge that now I’ve got corporate quality and audit threatening to come down here to go through my operation with a fine-toothed comb. You’ve spent the last two weeks taking a look at what they’re doing in operations. I expect that by now you’ve pinpointed the problems and know what to do about them. I’m ready to hear what solutions you have for us, and I’m ready to hear them right now.”

Leslie took a deep breath and leaned slightly forward in her chair. This was always one of the hardest parts of her job: helping clients understand that she wasn’t going to provide them with immediate solutions but, instead, would help them learn to see what and where the obstacles were that were causing the problems their customers were experiencing. “Sam, I understand how upsetting it is to lose one of your biggest customers. And you’re right, I have been spending time getting an understanding of what’s going on in your credit transaction processing operations, and I’ve been able to see some of the problems firsthand. What I’ve learned from watching how the credit transaction processors do their work is that a number of the processes that they use don’t support your vision of processing ‘every customer’s credit transaction right and on time, every time’—especially when processing more than 10 credit transactions at a time for your larger customers. I know that you really wish that I could offer you a ‘quick fix’ that would make all the problems go away, but in my experience, there isn’t any.

“I know that this may seem counterintuitive, but I believe that what we really need to do is put together a team of the people who do the work—the people who really understand how the work is done and know the problems from the customer’s point of view—to study the problem in depth, identify the obstacles that are causing problems for your customers, and come up with what we call ‘countermeasures’—possible solutions—to those problems. We’ll then test the countermeasures to see if they solve the problems.”

Leslie paused a moment to let Sam absorb what she had just said. “Think about it, Sam. When you just put ‘Band-Aids’ in place to try to ‘fix’ the problems in the past so that you could make your numbers, what happened? The problems seemed to go away for a little while and then they just came back. If we want a different result, we’re going to have to try something different.”

Sam looked at Leslie thoughtfully. This wasn’t what he expected, but he had to admit that what she was saying was correct. No matter what they seemed to try, the problems kept coming back, and now they seemed to be getting worse. “Leslie,” Sam said, “this isn’t what I expected, but at the moment, things are so bad that I’m willing to give anything a try.”

Leslie smiled and said, “Thanks, Sam. The first thing we’ll need to do is put a team together. We’ll need credit transaction processors, people from their supporting departments, and some managers. And we’ll need a ‘lead’ for this ‘pilot’ project. When I was visiting operations, I spent a good deal of time with Joe, one of the CTPMs. He’s really thoughtful, and I think he might be a great lead. He was willing to spend time with his credit processors watching how they do their work so he could see where the problems are coming from. He seems very open to learning, and that’s exactly what we need. I’ll need your support to get the ball rolling and get John, your regional manager, to approve the time and the resources.”

Sam didn’t say anything for a minute. Then he got up from the table where he and Leslie had been sitting and moved to his desk. “Leslie, I’ll send John a note now. I know he’s not going to like giving up the resources and the time—especially since we’re under such close scrutiny at the moment. But we’ll give your way a try.” Sam typed for a couple of minutes. Shutting his laptop, he moved back to the table where Leslie was still sitting, looking calm and collected as ever.

“Thanks, Sam,” Leslie said. “This is going to be a new way of thinking and working for NL Services, so your support is going to be unbelievably important. We need to solve the problems your customers are having. Right now, you hear about the problems from corporate, when your numbers are low or customers leave. But I have to ask you, when was the last time that you went over to operations to see what was happening for yourself?”

“Go to operations and see what’s happening?” Sam thought about it for a moment, realizing he couldn’t actually remember the last time he’d gone over to operations. “Leslie, to be honest, I haven’t been over to operations in a very long time. Too long. Can’t seem to find the time between phone calls from corporate, I guess,” he laughed. “But if you think that’s what I need to do, I’ll do it. Since nothing else has worked, I’m willing to give your way a try.”

Reflection: Narrowing Problem Space and Establishing the Team

In this meeting Leslie is energized by her time at the gemba and she sees Sam in his usual state of panic seeking solutions to today’s problems. Again, Leslie will not bite. Instead she points out the large gap between the vision he crafted and the current reality. She has selected John’s region for the first pilot program; she knows that it is important to win over John, and she also knows she needs strong support from Sam to move forward. There is a clear direction. She needs to pull together a team that will work through customer issues—as an outsider, Leslie cannot solve the problems of NL Services in a sustainable way. She is also continuing to coach Sam to change his way of thinking and managing—a shift from fighting fires to make the numbers by remote control, to going to the gemba to understand the actual concerns of customers and how they are handled by his organization. In so doing she is teaching him to put into practice one of Dr. W. Edwards Deming’s 14 Points:

Point 2. “Adopt the new philosophy. We are in a new economic age. Western management must awaken to the challenge, must learn their responsibilities, and take on leadership for change.”

UNDERSTANDING THE CURRENT STATE

Leslie had arrived early. The parking lot of the operations building had almost been empty. But she wanted to give herself enough time to set up and review and make sure everything was ready. She taped the long piece of butcher paper that would later become a diagram of the process steps used by credit transaction processors to the wall. She then reflected on her meeting with Sam and thought,“I’m definitely lucky on this one.” Sam was much more open to listening than most of the senior leaders she encountered. And not only was Sam willing to listen, but he actually had made good on his promise of going to see for himself.

True to his word, two weeks ago Sam had cleared his calendar, and they had spent the morning in operations, watching and listening as the credit transaction processors answered calls and entered transactions into the system. Sam had obviously been surprised. “Not at all like I remember it,” he had said to Leslie. “Why do the credit transaction processors have so many papers on their desks? And why do they have to keep getting up and going over to look for their CTPMs? Every time they leave their desk, the phone rings, and they miss a call from one of our customers. And even more importantly, where are the CTPMs? They don’t ever seem to be in their cubicles.”

Leslie was pleased that Sam had been paying attention and was asking so many questions. “Not sure, Sam,” said Leslie. “Only way to find out is to ask.”

Sam had spent another hour or so talking with the credit transaction processors and the one CTPM that could finally be found. Leslie could see that Sam was listening carefully. As the credit transaction processors headed off for lunch, Sam and Leslie found a small conference room to sit in. “Leslie,” said Sam. “I have to admit that I am really surprised by what I’m seeing and hearing. I know that the numbers I get from corporate haven’t been good, but every time I ask the regional managers about it, they send me spreadsheets and PowerPoint decks showing that everything is getting better. Just from spending the morning here, though, I can see that things are really a mess. The CTPMs are never around, the phones are ringing off the hook, its obvious that the credit transaction processors can’t keep up and aren’t happy, and if I were a customer, I wouldn’t be happy either. And I wouldn’t have believed it unless I’d seen it for myself. We’ve got to do something, and we’ve got to do it fast.”

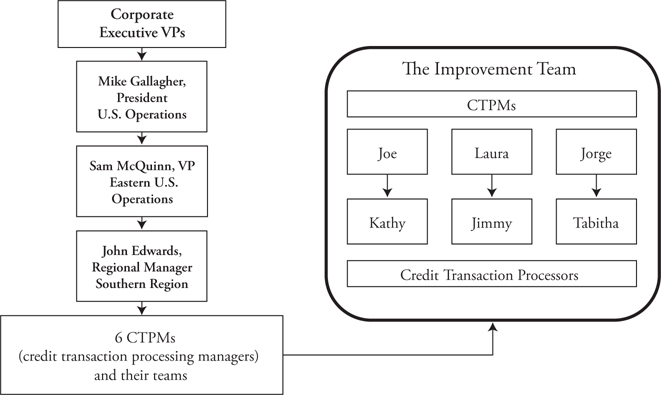

And so this morning, Leslie was preparing to work with a team of three credit transaction processors and three CTPMs that Sam and John, the regional manager, had helped her put together. The six team members headed for the small conference room to meet Leslie (see Figure 4.2).

NL Services, Inc. Organizational Chart

Figure 4.2 NL Services organizational chart and improvement team, which was made up of representatives from three of the credit transaction processing teams

Although the team members had been a little bit skeptical at first—“After all, we’ve been telling our CTPMs about the problems for years, and no one’s listened to us before,” Kathy, the credit transaction processor that Leslie had spent time with on her first visit to operations, had said—things were different now that they saw how serious Sam looked.

“When have we ever had three days off the phones to do something like this?” Tabitha, one of the other credit transaction processors on the team, asked. For a change they were getting excited that something positive might happen. Rounding out the team were Joe, Kathy’s CTPM; Jorge, Tabitha’s CTPM; and Laura, a CTPM, along with one of Laura’s credit transaction processors, Jimmy.

“I trust Leslie,” Joe had assured them. “She came and watched Kathy and me work, and after she saw what was going on—especially the problems with transactions with more than 10 lines—she really got Sam all fired up and got the ball rolling. I really believe she is going to be able to help us figure things out so we can make things better for us—and our customers.”

At 8 a.m., just as Leslie finished taping up the flowchart paper, the members of the team arrived. Settling into their seats, sipping their morning coffees, they looked expectantly at Leslie.

“Good morning everyone,” Leslie said cheerfully. “I’m so excited to be working with all of you. We’ve got a lot of work to do over the next few days, but I believe that we’re going to all learn a lot that we’ll be able to use to help us and our customers. Thank you so much for agreeing to be on this team. I know that this is a new way of working at NL Services, so I appreciate your willingness to give it a try.” Leslie paused for a moment as she handed out a template that she had created for the team to use.

“Before I explain what this template is for, I have a quick question for the team,” Leslie continued. “How many of you think that all the credit transaction processors do their work in the same way?”

Tabitha answered first. “Absolutely,” she said. “We all receive the same training, and we have SOPs for each type of credit transaction. And we all want to do what is best for our customers.”

Jimmy and Kathy nodded their heads vigorously in agreement with Tabitha. “And we all sit so close to each other,” said Jimmy. “I can hear what the other credit transaction processors on my team are saying to customers, and I can pretty much guarantee, we’re all doing our work the same way.”

“CTPMs,” asked Leslie, “what do you think?”

The three CTPMs looked back and forth uncomfortably from Leslie to each other. Finally, Jorge, in a low voice, said, “Leslie, I’m going to be honest here. I have no idea. I assume they do—my team members are all good people and do their best to make our customers happy every day—but between going to meetings, reading reports, and answering e-mails, I really don’t have any time to spend figuring out how the credit transaction processors do their work. Truthfully, when I really think about it, I have no idea how any work gets done on my team.”

Leslie walked over to stand beside Jorge. Looking at him kindly, she said, “Jorge, thank you so much for your honesty. It takes a lot of courage to admit that you don’t know. When we go to work, we aren’t paid for uncertainty—to ‘not know’—but to be certain and know things, especially as a supervisor or manager. In my experience, though, oftentimes the assumptions that we have about how we work and how things get done for our customers are just that—assumptions. And as we all know, assumptions are, more often than not, wrong. So this morning, what we’re going to do is go on a ‘fact-finding mission.’ We’re going to go to the gemba—that’s the word that we lean folk use for the place where the actual work that our customers want and need us to do for them gets done. And we’re going to record what we see and hear so we can find out what the facts are.”

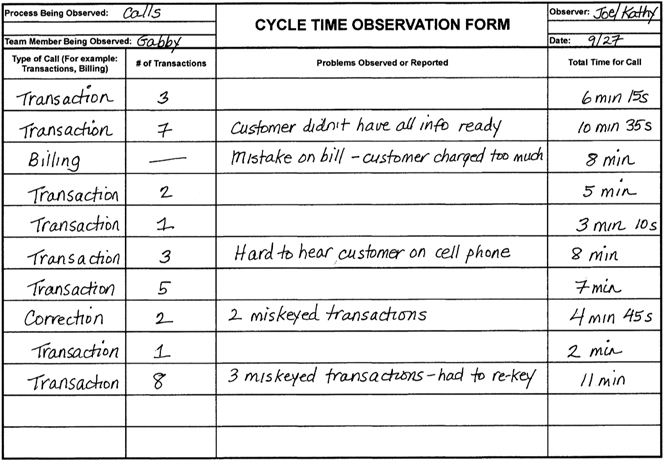

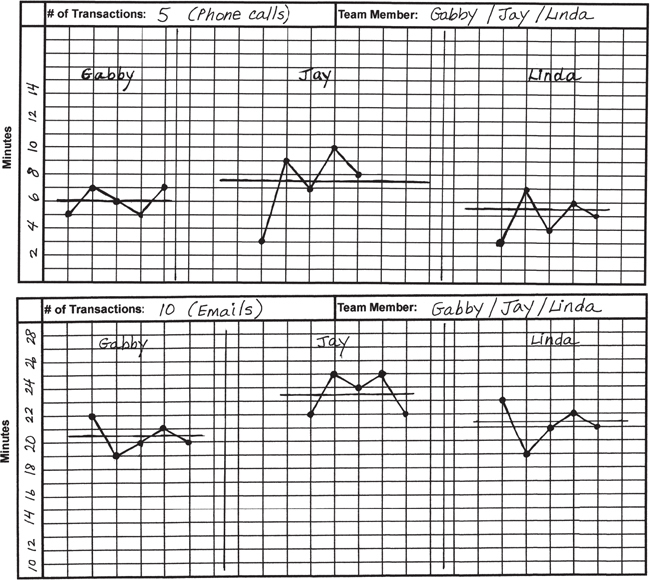

Leslie then spent a few minutes explaining how to use the templates that she had distributed. They would use two different forms in two stages of observation. In the first stage, each CTPM and credit transaction processor pair would spend one hour listening to another credit transaction processor answering calls and then one hour watching that credit transaction processor enter e-mails. For this first stage they would simply time cycles of work. How long did it take for each case from start to finish? There was also a place on the form for general notes about the transaction. They would also note what type of call it was in case this made a difference in the times (see Figure 4.3). They would use this information to plot a run chart of how long it took for each call (on one chart) and e-mail (on a second chart) and get a picture of the variation in cycle times by type of work and credit transaction processor doing the work.

Figure 4.3 Cycle Time Observation Form

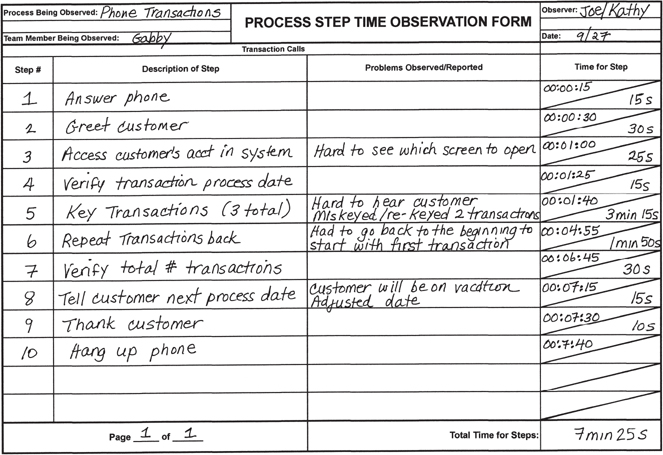

In the second stage they would then spend half as much time observing using a more detailed form showing steps followed. There would be one sheet to fill out for each call or e-mail. The CTPM would write down the steps used by the credit transaction processor in the first column on the left-hand side and add any comments or notes about interruptions or problems in that step in the column beside it. The credit transaction processor would time each step and record the time for each step in the right-hand column. They’d use one sheet per call or e-mail. They would also record the call so they could confirm times (see the form in Figure 4.4). This second stage would lead to a detailed picture of the steps followed, the sequence, and the time per step for different tasks and different credit transaction processors.

Figure 4.4 Process Step Time Observation Form

As Leslie explained the process, she could feel a combination of nervousness and excitement in the room. They’d never done anything like this observation before, but finally, after years of frustration, something was happening. After she finished, the CTPMs and credit transaction processors spent a few minutes discussing among themselves whom they would sit with to observe. Once they were organized and Leslie was comfortable that everyone knew how to use the forms, she sent them off. “I’ll be around to check on you,” she reassured everyone. “I know that you’ll all do a great job.”

“Leslie,” said Laura, “this is so exciting! I feel just like a detective. I can’t wait to see what we find out!”

Two hours later, the team members reconvened around the conference room table. After a few minutes organizing themselves and posting on one section of the board the run charts and on another the activity timing sheets, they looked expectantly at Leslie. “Well,” said Leslie, “what did you think?” Everyone started to talk at once.

“I didn’t realize that customers made so many changes in the credit transactions that they were calling in,” said Laura.

“And that Kelly, my teammate, doesn’t follow the same steps to enter the credit transactions as I do,” chimed in Jimmy.

Kathy broke in, “And you know that ‘more than 10-line’ problem I’ve been having? Well, Erica said that she was having it too!”

“Now that we have all this information, what are we going to do with it?” asked Tabitha.

Leslie laughed and said, “Now you know why I was so excited this morning. Going to see what’s really going on gives us a very different view of what is happening. I’m glad that everyone saw and heard so much. The next step is for us to take the information that we’ve gathered and put it together in a way that we can all ‘see’ what story it’s telling us.” Leslie pointed to the wall where she had hung up a number of pieces of flip-chart paper. On one page she had printed the heading “Process Timing Run Chart—Less Than 10 Transactions”; on another, she had written “Process Timing Run Chart—10 Transactions or More.” On the third page she had printed “Problems Observed.” For the next half an hour or so, Leslie worked with the members of the team to help them create graphs to analyze the data and observations that they had collected on the flip-chart pages. They posted a run chart for each of the transaction processors they observed. When they were finished, what they produced looked like the run charts in Figure 4.5.

Figure 4.5 Run charts for <10 and >10 transactions

Sitting back in their seats, the team members focused on Leslie as she instructed them to take a few minutes to think about what they saw. Looking around, she could see that they were quite surprised.

Joe spoke first: “Leslie, look at the difference in the time that it takes to process the credit transactions. Some take such a short amount of time, and others take so long.”

“And look how long the transactions with more than 10 lines actually took!” exclaimed Jorge. “My team has so many large customers. I didn’t realize it took so long to enter those transactions.”

Kathy, who had been excitedly waiting her turn to speak, interjected, “And look at the chart of the problems . . . transactions with 10 lines or more are definitely the biggest problem, just as I suspected!”

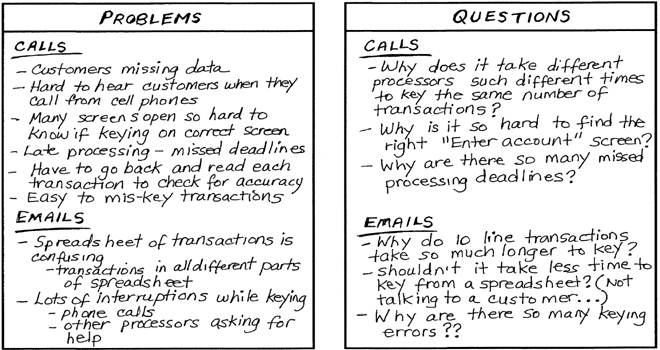

Leslie congratulated the members of the group on their excellent observations. Then she taped up another piece of flip-chart paper that she labeled “Questions” (see Figure 4.6). She then described the next step: “We need to look at this great data and analyze it. First, what problems did you see in the processes?” The group called out problems and Leslie separated them by problems with calls and problems with e-mails. Then, for the next 15 minutes, she helped the team brainstorm a list of questions that seeing the information on the charts made them think of.

Figure 4.6 Flip-chart notes of problems and questions

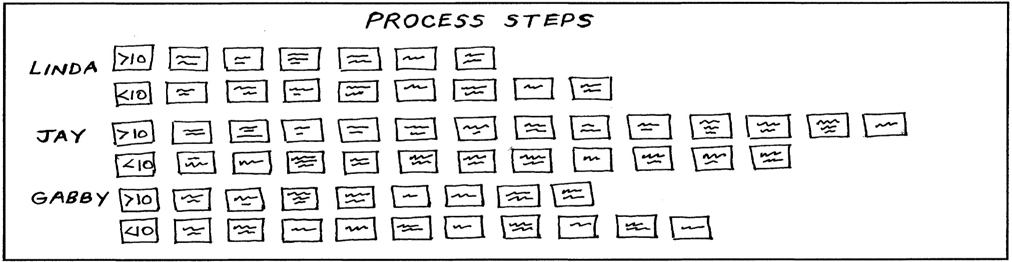

After everyone had a short break, Leslie said, “Team, we have one more thing to do before lunch. I think you are really going to enjoy this.” Turning to the long piece of butcher paper that she had labeled “Process Steps,” Leslie said, “Remember when I asked whether you thought all the credit transaction processors used the same steps to do their work? And everyone ‘assumed’ that they did? Well, now we’re going to find out whether our assumptions were correct. What we’re going to do next is create a diagram that shows the steps, in sequence, for each credit transaction processer, and then we can compare them.”

As Leslie handed out a pad of colored Post-it notes to each person, she continued, “Using your timing sheets, write out the steps that the credit transaction processor you observed used to complete the transaction. When you’ve finished writing out the steps, one per Post-it note, come up here to the butcher paper and stick the Post-its up in order.” To make things clearer, Leslie put a Post-it note with each transaction processor’s name on it up on the butcher paper so that people could see where to start their row of notes. “Once all of you have put up your Post-its, we’ll be able to see if the steps are the same or not.” Twenty minutes later, the butcher paper, filled with colored Post-its, looked like the one in Figure 4.7.

Figure 4.7 Process steps diagram by processor

Leslie was not surprised at what the team had created, but she knew that the team would be. Looking at the process steps diagram, it was obvious that no credit transaction processors did the work in the same way. Standing back, Leslie waited for the team’s reaction. After a few moments, Joe spoke first. Laughing he said, “I would not have believed it if I had not seen it laid out clearly like this. Leslie, we thought that everyone was doing the work in exactly the same way. But it’s obvious that no two people are doing the work the same way! No wonder we have so many problems. No wonder it takes some people longer to do the same work than others. Everyone we sat with was very confident that they were working exactly the way that they had been trained to! Our assumptions this morning were definitely wrong!”

“Definitely,” agreed Tabitha. “How could we have been so sure of ourselves? And now that we can see that everyone is doing the work differently, and that processing the transactions takes different people such different amounts of time, and that we have so many problems, especially with transactions that have more than 10 lines, what are we going to do about it?”

“That,” answered Leslie, “is exactly what we’re going to discuss . . . right after lunch!”

Reflection: Understanding the Current State

The current state is starting to reveal itself, and the team is getting excited. People are getting excited because they are accountable for the process of discovery. Many things were clear to Leslie from the beginning, but she was not going to reveal her own observations. First, she was not certain of her own observations and wanted real data and facts. Second, she needed to teach the members of the team how to see the state of their own processes. It is interesting that they lived in this organization and yet had strong misperceptions, for example, assuming all the credit transaction processors do the work in the same way, following the SOPs. Through structured observation it immediately became clear they were wrong. Leslie asked the question because she wanted public predictions. This was not to make fools of them, but so they could learn about the dangers of assumptions and about the gap between what they assumed and reality. People learn more by becoming aware of gaps between what they think they know and what they actually know than by being consistently right.

IDENTIFY GAPS AND PRIORITIZE

Prioritizing What to Strive For

When they returned from lunch, Leslie was pleased to see how obviously excited the team members were to continue their work. For the first few moments, they gathered around, chatting among themselves and pointing things out on the charts. After they all had finally settled back into their seats, Leslie said, “Team, I’m really proud of the work you did this morning. Looking at the process steps diagram and the other charts on the wall, we can see how much we’ve learned already about the wide variation in the way credit transactions are being processed and what some of the problems are. Now, as a team, we need to decide what we want to tackle to make the process better for everyone—especially our customers.”

“Yes,” said Tabitha, a little nervously, “I agree. But as I was saying before lunch, we seem to have so many problems, how do we know where to start? We can’t work on everything all at once . . . can we?”

Leslie smiled and shook her head. “Tabitha,” she said, “you’re right. Sometimes when we have problems, we try to tackle a lot of different things and try a lot of different solutions, all at the same time. Has anyone here ever experienced that?”

Jorge said, “Leslie, are you sure you don’t actually work at NL Services? Every time our numbers dip down, corporate yells and screams so much that we CTPMs make a list of every possible problem and every possible solution, and we just start trying to do all of them as quickly as we can. We just throw things at the wall and hope something will stick!”

Laughing, Leslie nodded her head and said, “Jorge, I promise you that I haven’t worked at NL Services before, but I’ve certainly seen exactly what you’re describing in many different places. And in my experience, it doesn’t work very well: when we try to tackle too many things at once, we can’t focus, and we don’t end up doing anything well. And we can’t understand why something worked or why it didn’t.”

Looking around the room, Leslie could see that the team was in agreement. “I’m going to suggest we try something different this time,” Leslie said. “Let’s decide together on one or two problems to work on and go from there.” She continued: “I know we’ve identified a lot of problems. Can anyone think of a way that we could choose which we should start with?”

Kathy, who had been staring at the process steps diagram and run charts the whole time that Leslie had been speaking, suddenly turned to Leslie and the team. “Leslie,” she said, “when I look at the run charts, what jumps out is that ‘Transactions with more than 10 lines’ take a lot more time to process. And we know that when there are problems with those transactions, our customers get fines from the state, and sometimes they’re so angry that they change credit transaction processing companies. That’s what happened three weeks ago with my biggest customer, E-Z Credit. Errors on transactions with 10 lines or more is a problem that’s really bad for our customers—and it’s really bad for us.” Looking around the room, Leslie could see the team nodding in agreement.

Getting up from his seat and going over to the process steps diagram, Jimmy zeroed in, “Just look at this. You can see that none of the credit transaction processors do their work in the same way. It’s no wonder that the run charts show that there is so much difference in the amount of time it takes to process the credit transactions. And I can’t tell you how often my customers call and complain that their transactions aren’t processed on time. Maybe if everybody worked in the same way, it would take less time and we could get the credit transactions processed when our customers want them.”

Looking around excitedly, Tabitha said, “Maybe that’s it—our charts and graphs are showing us that the two problems we should start with are fixing the problem with transactions that have 10 or more lines and figuring out how all the credit transaction processors can do their work in a way that all the credit transactions get consistently processed on time! If we can fix those two problems, our customers will be happier, and we’ll be happier too!” Jorge, Laura, and Joe agreed with the credit transaction processors. If they could make a dent in those two problems, they’d certainly get fewer angry phone calls from their customers—and from corporate.

“Great job, team!” exclaimed Leslie. “Looking at the work that you did this morning, I agree that fixing those problems will be of great benefit to your customers—and your colleagues. I find it useful to think in terms of what we are trying to strive for rather than what problems we are trying to fix. For each of these two problems, what would success look like?”

Kathy looked thoughtful. “I guess if I stated the 10-line problem as something to strive for, I would say that we need accuracy and low processing times regardless of the number of lines.”

Jimmy joined in, “And for the other problem, we would like a consistent, quality process regardless of which credit transaction processor does the work. Now that I think about it, in both cases we want consistency and quality, and these are two different obstacles to those goals.”

“I like it!” said Leslie. “Looking at the data that we have now, though, I’m not sure that we know enough about what’s really going on in the transactions with 10 lines or more. My suggestion is that we spend the next couple of hours learning as much as we can about how those transactions are processed. Anyone have an idea of how we could do that?”

“Let’s go back to the gemba and look and listen more,” Kathy suggested. “I know how we can look up which credit transaction processors have transactions with 10 or more lines to process this afternoon. We could ask them if we could sit with them while they process the transactions so that we could see how they do it and what problems they are having.”

“And,” said Jimmy, “we could look really carefully to see how each of them is doing the process—record the steps again and then map them out to see if anyone has found a way to do the process more efficiently and with fewer errors.”

“Plus,” Tabitha said, “one of my best customers, Credit A2Z, always sends in transactions with 10 or more lines. I bet if we called the people there, they wouldn’t mind telling us about how they feel about our processing. That might help us figure things out too.”

Twenty minutes later, Kathy had distributed a list of all the transactions with 10 or more lines that were going to be processed that afternoon, and Jimmy and Tabitha had talked with all the credit transaction processors who were going to process those transactions to let them know about what the team was doing. Timing sheets in hand, the members of the team set off to learn as much as they could. Leslie promised that she would come and get them two hours later.

Reflection: Identifying Gaps and Prioritizing

Organizations often either experience a lot of angst over what problems to start with or else develop a laundry list of problems, quickly identify solutions, and then create an action list of who will do what and by when. Both are mistakes.

In the first instance, it actually is not critical that the team identify the optimal problem to work on at the outset. If the teams follow an approach of rapid experimentation they can quickly test their assumptions about the impact of solving various problems. There are a number of ways to quickly prioritize problems. Teams often use a simple 2 × 2 effort-impact matrix to classify problems by the likely cost of solving them and the potential impact on the customer and business. Obviously it is desirable to start with low cost and big impact problems. But we are still making subjective assumptions, and it’s not until we run the experiments that we will learn if we are correct.

Developing long action lists is usually ill advised, as Leslie points out, because if many “solutions” are developed and many things implemented simultaneously and we see a change in the outcome, it is impossible to know what is having the impact, positive or negative. Single-factor experiments—in other words, trying one thing at a time—are ideal for learning what works and what doesn’t.

STRIVE FOR FUTURE STATE THROUGH SMALL CYCLES OF LEARNING

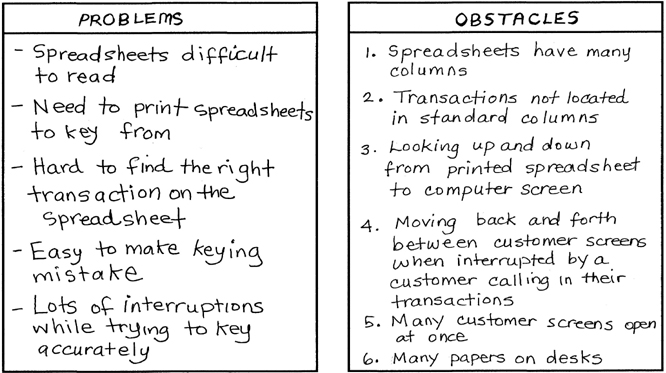

PDCA Cycle 1: Deeper Dive at the Gemba

That afternoon, they all did their gemba study as agreed. At exactly 3 p.m., true to her word, Leslie gathered the team together, and they headed back to the conference room. As soon as they arrived, before Leslie had a chance to settle the team, Joe took a piece of flip-chart paper, stuck it to the wall beside the run charts they had made in the morning, and wrote “>10-line transaction problems.” As the members of the team began to call out more of the problems that they had uncovered while sitting with the credit transaction processors, it soon became obvious that the majority of problems happened when the credit transaction processors entered the transactions from e-mails that customers sent in. When the team added up the number of 10-line-or-more transactions with which the credit processor had had a problem, there were three times as many that were submitted by e-mail.

“Interesting,” Laura said. “I wonder why that would make a difference?”

“I have some ideas about that,” Kathy answered. “When we enter credit transactions that have more than 10 lines, the information usually comes in an Excel template attached to the e-mail. When we open up the spreadsheet, there are 20 to 30 columns that have all kinds of information in them. We don’t need to use most of it—just the transaction numbers and the dates. But in order to find those, we have to scroll back and forth across the columns and then up and down the different rows. It’s like being a detective looking for what you need. Sometimes the spreadsheet is so big that we print it out so that we can highlight the transaction numbers and dates before we try to key them into the system. Whether you do it on the screen or from the paper, if you’re not really careful, it’s easy to make a mistake and pick up the wrong number in the wrong column.”

“And all that hunting and pecking for the right number in the right column takes a long time, too,” Tabitha noted.

“I’ve had that problem lots of times myself,” Jimmy added. “And it’s even worse when you’re scrolling back and forth on the Excel template trying to get all the right transaction numbers, and the phone rings. Then you have to stop, open another window, process the credit transactions for the customer on the phone, and then go back and try to figure out where you were on the 10-line-or-more transaction spreadsheet. I’m always worried I’ve made a mistake when that happens, no matter how many times I check the transaction before I send it out.”

“You know what, Jimmy?” Jorge said. “Lexi, the credit transaction processor I was sitting with, said exactly the same thing. She said that e-mail transactions with 10 or more lines were the worst because she knew she was going to be interrupted and probably make a mistake. She said she got a stomachache every time she had to process one.”

Kathy finished the conversation by adding, “Think about it. When we process credit transactions by phone, the customer reads us the transaction number, and we repeat it back after we enter it. If it’s wrong, we just fix it right away. And if we’re on the phone already, no one can interrupt us!”

As the team continued to add to the list of problems, Leslie tore off another piece of flip-chart paper and stuck it on the wall beside Joe’s. Under the heading “Obstacles,” she listed six points, as shown in Figure 4.8.

Figure 4.8 Flip-chart pages of Joe’s list of problems and Leslie’s list of obstacles

After she finished writing the list of obstacles, Leslie checked her watch and said to the team: “Wow! It’s almost 4:30. Time certainly has flown by. I think we’re at a really good stopping point for today, but before we go, let’s make a plan for tomorrow. Now that we have more information about the 10-line credit transaction problem, I’d like to suggest that we break up into two teams. One team will work on figuring out how to create a process that all the credit transaction processors can follow so that it takes a similar amount of time to enter similar kinds of credit transactions, and one team can work on figuring out how to overcome some of the obstacles in the 10-line transaction process. How would everyone feel about that?”

Kathy and Joe looked quickly at each other and the team. Kathy said, “If everyone else is okay with it, I’d love it if Joe and I could work on the 10-line problem. I’ve complained to him about it so long and so often, I’m sure he thinks I’m like a broken record. But I’m only complaining because the problem is so important to me. And if I can do something to stop customers like E-Z Credit from leaving, it would make me really happy.”

“Absolutely,” said Laura. “Absolutely.”

“Great!” said Leslie. “We’re all set for tomorrow. Kathy and Joe will work on the 10-line problem, and Tabitha, Laura, Jimmy, and Jorge will work on figuring out how to create a process that will allow all the credit transaction processors to do a quality job on time for each customer.”

Chatting among themselves, the team started packing up. As Jorge headed out the door, he almost collided with Lexi, the credit transaction processor he had sat with in the afternoon. “Jorge,” Lexi said, “when you asked to sit with me today, I was a little nervous at first. But then when I saw you taking detailed notes and realized how interested you were, I began to get excited about it. I just wanted to come by and tell you that.” Then seeing the charts and flip-chart pages on the wall, Lexi said, “Looks like you guys did a lot of work today!”

“We sure did,” said Jorge. “And we couldn’t have done it without your help—and the help of all the other credit transaction processors. Let me show you what we learned.”

As Leslie watched Jorge explain the run charts and process steps diagram to Lexi, she smiled to herself. “Always best to go to the gemba and see for yourself. Works every time.” It had been a great day today, and Leslie was sure that the next two days would be even better.

Reflection: Deeper Dive at the Gemba

We often think of PDCA at a macrolevel where we develop a plan for the entire problem, then implement it, then check what happened, and then define further actions. In any effort to improve complex processes, there are many embedded PDCA loops. And PDCA does not necessarily mean we “implement” something. It can mean we check our assumptions through further study. In this case the plan is determining what to study, for example, the 10-line problem, and how it will be checked. Then the doing is going to the gemba to do the study. Then we discuss what we saw and learned and define next steps.

PDCA Cycles for the 10-Line Problem

Over the next two days, both teams would be surprised at the amount of progress that they could make with Leslie’s help.

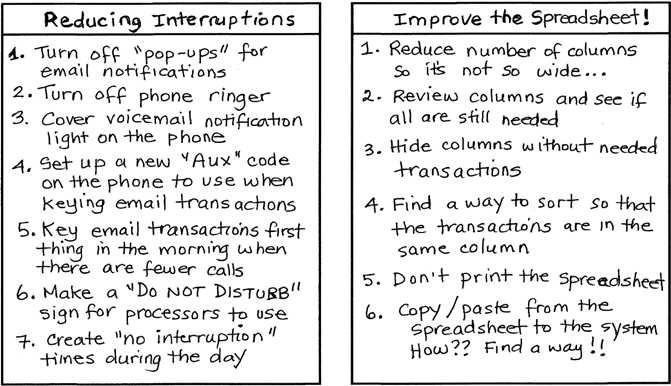

Reviewing the data that they had gathered on the transactions with 10 or more lines and the list of obstacles that they had created, Kathy and Joe decided to concentrate on two things: finding ways to reduce the amount of interruptions that the credit transaction processors were having when entering e-mail transactions and seeing if there was a way to change the Excel template that contained the transaction numbers they needed to enter. They put up two flip-chart pages on the wall and brainstormed ideas. After about 20 minutes, they had generated two robust lists (see Figure 4.9). Sitting down at the conference room table, Kathy pondered, “Joe, now that we have all these ideas, I’m just not sure how to choose which one—or ones—to try first . . .”

Figure 4.9 Flip-chart pages with ideas to improve the 10-line-or-greater transaction process

Joe agreed: “I’m not sure either. Maybe we should see what Leslie thinks.”

Leslie reviewed both lists of ideas with the team. “Excellent work,” she said, standing back and looking at the lists. “I can see how you are having trouble deciding—and also why you are tempted to try everything at once. So many good ideas that might help. However, remember when we talked yesterday about trying too many things at once? When we do that, we don’t have a way of knowing what, if any, of the things we tried moved us toward the target. In my experience, choosing one thing to change, trying it out, and seeing what happens is a better way to learn about what works and what doesn’t.”

Leslie then went on to explain PDCA, the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle to them (see Figure 4.10). “Trying things out with PDCA doesn’t have to take long,” Leslie explained. “It’s like doing an experiment when you were in a lab in high school. You choose something to try that you think will make the problem better—you make a prediction about what is going to happen—then you try it out in a quick ‘learning experiment.’ We call that testing a countermeasure. Once you’ve tried your countermeasure, you can see if your prediction was actually correct . . . Did what you think was going to happen actually happen? Or did something else occur? Working like this helps stop us from making all those ‘assumptions’ that we all love to make.”

Figure 4.10 Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle

Leslie smiled and looked at Joe and Kathy. Kathy looked at Leslie and then at Joe. “So,” said Kathy, “if I understand correctly, we need to choose one of our ideas, figure out how to try it out quickly, and then do what we did yesterday! Go to the gemba with our timing sheets and see what happens when we try it out!”

“Absolutely correct,” said Leslie.

With a thoughtful look on his face, Joe said, “It sounds like we don’t need to get too hung up on trying to figure out which one to try first. We don’t know what is going to happen with any of them. They’re just ideas now. Until we try them out, we won’t know which one is better. We can only guess. And our guess could be right or wrong. The important thing is to pick one, try it, and see what happens. Then we can move on.”

“Absolutely correct, once again,” said Leslie. “How many times do we get stuck trying to figure out what would be the best thing to try? Since everybody has an opinion based on his or her own personal preference, often nothing actually gets done.”

Joe started to laugh. “Leslie,” he said, “I know you keep saying that you haven’t worked at NL Services before, but I am not sure that I really believe you.”

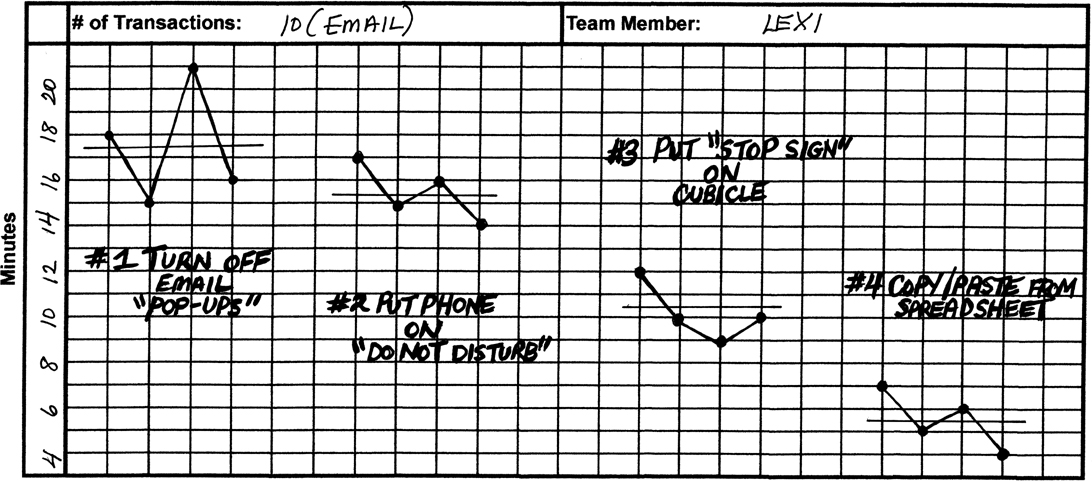

Joe and Kathy decided to work on reducing interruptions first. Jorge asked Lexi, the credit transaction processor that he had spent time with the day before, if she would be willing to help Joe and Kathy try some things out. Lexi enthusiastically agreed to help. For each “countermeasure” they tried, Joe and Kathy used their timing sheets to see how long it took to enter the transactions with 10 or more lines. They also kept a record of how many errors were made.

By lunchtime, with Lexi’s help, Kathy and Joe ran three experiments to test what happened if the credit transaction processors turned off the pop-up alerts on their e-mail, put their phones on “do not disturb mode,” and taped a small red stop sign with the number 10 on it to the side of their cubicle wall to let other credit processors know that they were processing a transaction with 10 or more lines.

When they got the results of these three experiments, they discovered that the amount of time to process a 10-line transaction was cut in half and the number of errors was reduced by about one-quarter. Joe and Kathy were excited to share the results of their “learning experiments” with Leslie. “Great work, team!” Leslie exclaimed. “Looks like you’ve found some good countermeasures.”

“Yes,” agreed Joe. “This afternoon, we’re going to work on some changes to the Excel spreadsheet. You can see that the amount of time it takes to enter the 10-line transactions has gone down a lot. But there are still too many errors.”

“And no customer wants to have errors in their transactions,” reminded Kathy. “It’s not really going to help our customers if we process their work on time, but there are mistakes. Then they’ll still get penalties from the state. We need to process their transactions on time and error-free! When we were sitting with Lexi, we could see how many problems using the printed spreadsheet caused her. She had a lot of great ideas about how to fix them that we added to our list, and we’re going to work on those this afternoon.”