Appendix A

Phi Phound Me

In my other books, I proved debt can be beneficial, but my earlier books' inflexibility for people in the accumulation phase presented a series of new challenges:

- How can you create a flexible, dynamic debt ratio range that moves throughout your life in a responsible way?

- How can the range be customized for different levels of assets and different levels of income?

- How can a dynamic, flexible range be overlaid with some of the greatest theories in finance?

- How can we test results without knowing the future? Most people test using historic data, but the results can be incredibly misleading.

- Could we reverse the test by considering what assumptions you would need to believe to find value in debt?

- Could this process help create an informed discussion composed of a world of unknowns?

- In addition to giving debt mathematical value, can we test the value of debt in reducing stress?

- If it turns out that the theories test well, how could they overlap with behavioral economics and our tendencies as human beings?

As it turns out, all of this was too difficult. Every strategy I derived was too complex or too rigid. I couldn't form a flexible, simple strategy to accommodate people of virtually any level of net worth and income that are still accumulating assets. I was stuck.

Inspiration Arrived

I visited the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago and saw a fascinating exhibit about math in nature and life. I learned about the sequences and proportions that can be found across objects young and old, big and small, created by nature or created by man.

Nature, art, architecture, and music all exhibit a natural balance. They have patterns that can be repeated and scaled. They aren't the same. There are a lot of differences between Saturn, the human body, and the Parthenon, but when looking at the balance of the proportions, you may be surprised how much they have in common.

What is even more amazing is how the proportions can be consistent throughout change. For example, your body exhibits similar proportions throughout your life, even as it grows and changes. Importantly, the proportions in your body are similar but rarely would be the exact same and they rarely, if ever, would conform exactly to a mathematical series.

Could we apply these ideas to your financial picture? Could we use this framework as inspiration to create a balanced glide path? Could this balanced approach be flexible and more dynamic than the simple example of the Nadas, the Steadys, and the Radicals? Could the result be a more beautiful and better representation of balance throughout our lives?

You likely remember the number pi from geometry class. Pi is an irrational number that cannot be represented by a fraction. It is an infinite series (3.14159…) that never ends nor moves to a permanent repeating pattern. This transcendental number represents the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter.

There is another irrational number that you may or may not be familiar with: phi. Like it's friend pi, phi is an infinite series starting at 1.618. This is a super cool number that is often called the golden ratio. The golden ratio is often called God's ratio because phi can be found literally everywhere, including in the proportions in:

- The human body

- Other animals

- Plants

- The solar system

- Mother Nature

- DNA

- Architecture

- Music

- The Bible

The Italian Renaissance artist Leonardo Da Vinci used the golden ratio in many of his paintings—and in fact, the golden ratio had a central role in the book and movie The Da Vinci Code. Phi is 1.618. Let's say that a line has a length of 1. Imagine that you break this line into two sections—one that is 0.618 in length and other 0.382. This break represents phi, or the golden ratio, which is sometimes rounded to “one third/two thirds.”

I have been familiar with phi for a long time and considered that perhaps the golden ratio of personal debt is 38.2 percent—which is really close to (though a bit higher than) the optimal ranges I recommend. In fact, the one third/two thirds ratio is the basis of the tests I conducted with some wonderful assistance from the Olin School of Business at Washington University in St. Louis in The Value of Debt in Retirement.

Still, phi represents a single number. It represents balance, but it is rigid. This is unsatisfactory, because as we have discussed, people's lives and incomes change over time. One number, one ratio, cannot give the flexibility people want and need. I had the seed of an idea, but I still lacked a flexible, dynamic framework.

The golden ratio can be derived many ways, including the Fibonacci sequence, which is named after an Italian mathematician. In The Da Vinci Code, the Fibonacci sequence plays a central role as the protagonist attempts to break an ancient code. The neat thing about the sequence is that it provides a series of ratios that can be used to look at proportions across objects young and old, big and small, created by nature or created by man. A series is more flexible so it can more easily evolve throughout life. For example, your body exhibits similar proportional ratios throughout your life, even as it grows and changes. Importantly, the proportions in your body are similar as you grow but they rarely, if ever, would be the exact same, and they rarely, if ever, would conform exactly to a mathematical series.

Not Perfect Makes Perfect

Leonardo Da Vinci, Beethoven, the ancient Greeks, Mother Nature, and your body all exhibit balanced traits from the Fibonacci sequence, but none are an exactly perfect fit to the series. I look to the Fibonacci sequence as an inspiration, but have no intention to force a fit nor to be precise. Some of the greatest works of art, architecture, music, and even our own bodies are not perfectly conforming! Perfection is boring. Perfect is not beautiful. Therefore, I am not looking for perfection, I am looking for a balanced path of inspiration that can accommodate a wide variety of shapes and sizes.

Applying the Fibonacci Sequence

The following is intended only for readers who find the inspiration for the math behind the book interesting. This book went through a dramatic evolution. The first version laid out concepts, but it wasn't specific or actionable and offered no proof to the underlying thoughts. I wasn't satisfied. Once phi found me, I rewrote the whole book emphasizing the math. In the second iteration of this book, the first chapter was called “The Debt Hypothesis.” In it, I formed a “null” hypothesis which, to me, represented the conventional wisdom held by most members of society:

Debt adds zero value. While most consumers use debt at some point, they desire to eliminate it as fast as possible because they believe that being debt free is financially responsible and will increase their financial security, reduce stress, and put them on a better path to financial freedom.

It is my belief that in the anti-debt hysteria world most people are (1) taking on too much debt too early in life; and then (2) paying down that debt too aggressively; and as a result they are (3) not beginning saving until later in life. It is my hypothesis that this strategy might be coming at a considerable cost to society and that there could be a better, more balanced path. This formed the basis for an alternative hypothesis:

We can embrace a sensible, balanced approach to debt throughout our lives; an approach that rhymes with the balance exhibited in nature, art, architecture, music, and even our own bodies. This balanced approach will reduce stress, increase financial security and flexibility, and increase the probability of a secure retirement. Used appropriately, strategic debt is not a waste of money, but rather, an opportunity to increase the likelihood you will be able to accomplish your goals in the short, medium, and long term.

From here, the book was a contest: a mathematical proof of The Value of Debt in Building Wealth. I laid out the alternative hypothesis and then tested the null hypothesis against it. Because I do not know your rate of return or your cost of debt, the book concluded with what you would need to believe in order to conclude that debt adds or destroys value in building wealth. While the second version was very math forward, the version you just read was more “concept forward.” For those who desire more specifics on the math, here are highlights behind the phases.

The Fibonacci sequence is written as follows:

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144…

You can see that each number is the sum of the two numbers before it. For example, ![]() ;

; ![]() . This sequence can be graphed as shown in Figure A.1. As the series grows, the numbers become closer and closer to the golden ratio. For example,

. This sequence can be graphed as shown in Figure A.1. As the series grows, the numbers become closer and closer to the golden ratio. For example, ![]() …

…

Figure A.1 A Representation of the Fibonacci Sequence

Notice that the first square has the dimensions ![]() , as does the second. Two is a

, as does the second. Two is a ![]() square. Its sides equal three and three is a square that is

square. Its sides equal three and three is a square that is ![]() . As we know, the golden ratio itself is a static infinite series 1.618033…. The Fibonacci sequence not only gives us a single number but also a series of numbers and therefore a series of ratios.

. As we know, the golden ratio itself is a static infinite series 1.618033…. The Fibonacci sequence not only gives us a single number but also a series of numbers and therefore a series of ratios.

The following are examples of Fibonacci ratios:

These ratios actually form the basis for the glide path presented in the book. We began with Phase 1: Launch! Table A.1 is a reprint of Table 3.3, which outlined the Launch Phase path in Chapter 3.

Table A.1 Blank Phase 1: Launch!

| Step/Goal/Bucket | Formula | A Balanced Path | Where You Are | Gap |

| No oppressive debt (No debt at a rate over 10 percent) | 0 | $0 | ||

| Cash reserve, build to a one-month reserve (checking account) | Monthly income × 1 | |||

| Start a retirement plan. Build to a balance of one month's income | Monthly income × 1 | |||

| Continue building cash savings until you have an additional two months' reserve (savings account) | Monthly income × 2 |

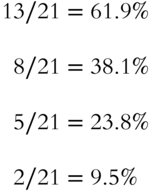

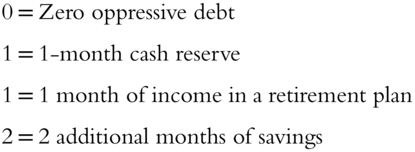

Recall the Fibonacci sequence begins: 0, 1, 1, 2. Our Launch phase series began with zero oppressive debt, 1 month cash reserve, 1 month of income in a retirement plan, and 2 additional months of savings. This could be written as follows:

The Launch phase starts out with a perfect tracking of the Fibonacci sequence. From here, we entered Phase 2: Independence. Table A.2 is a reprint of Table 3.8 from Chapter 3.

Table A.2 A Blank Balanced Path Worksheet—Phase 2: Independence, No House

| Goal/Bucket | Formula | A Balanced Path | Where You Are | Gap |

| No oppressive debt. No debt at a rate over 10 percent. | 0 | $0 | ||

| Cash reserve, checking account | Monthly income × 3 | |||

| Cash reserve, savings account | Monthly income × 3 | |||

| Retirement investing | Monthly income × 6 | |||

| Big life changes | Monthly income × 9 |

In math, we often use different units to measure. For example, something could be 30 yards away, 90 feet away, or 1,080 inches away. Each is the same distance, it is simply presented with different units of measurement. As the size grows, we typically use a different basic unit of measurement. You would not, for example, typically state the distance of Washington, D.C., to New York City in inches.

In the Independence phase, our goals were to have zero oppressive debt, build a three-month cash reserve, build retirement savings to six months' income, and establish a big-life-changes fund equal to six months of income. The Fibonacci sequence is written: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8. At the surface the numbers 0, 3, 3, 6, 9 appear to have little in common with the sequence. However, if you restate each of the goals into a basic unit where a unit is equal to three months of income, you could write it as follows:

- 0 = Zero oppressive debt

- 1= Cash reserve checking (equal to 3 months income / 3 = a basic unit of 1)

- 1 = Cash reserve savings (equal to 3 months income / 3 = a basic unit of 1)

- 2 = Retirement savings (equal to 6 months income / 3 = a basic unit of 2)

- 3 = Big life changes (equal to 9 months income / 3 = a basic unit of 3)

Said another way, if you divide each number of the series 0, 3, 3, 6, 9 by 3, you get 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, which is the Fibonacci sequence.

Next we discussed buying a house. Table A.3 is a reprint from Chapter 3 of Table 3.13. In Table A.3, however, I replace the columns “A Balanced Path,” “Where You Are” and “Gap” with “Fibonacci Numbers” and “Basic Unit,” which is the “Formula” column divided by the basic unit, in this case 3.

Table A.3 A Blank Balanced Path Worksheet—Phase 2: Independence, with a House

| Goal/Bucket | Formula | Fibonacci Numbers | Basic Unit (3 months income) |

| No oppressive debt (No debt at a rate over 10 percent) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cash reserve, checking account | Monthly income × 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Cash reserve, savings account | Monthly income × 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Retirement savings | Monthly income × 6 | 2 | 2 |

| House equity | Monthly income × 9 | 3 | 3 |

| Net worth | Monthly income × 21 | 8 | 7 |

| Mortgage | Monthly income × 39 | 13 | 13 |

| Total assets | Monthly income × 60 | 21 | 20 |

Note that the last number in the basic unit column is 20, where the Fibonacci sequence would have been 21. And note that net worth is a 7 in the unit column where it would have been an 8 in the Fibonacci sequence. This is where it is essential to recall that I am not trying to force a fit, I'm turning to the natural world for inspiration to test the alternative hypothesis against the null hypothesis.

In Chapter 4, we covered Phase 3: Freedom. From Chapter 4, “The goal of the Freedom phase is to reduce your debt ratio. Since reducing debt is the primary goal, then we need a different base unit, one that relates specifically to your debt. Therefore, do the following:

- Write down your total liabilities (your total outstanding debt) = ________

- Divide this number by 8 = ____________

This is your base unit for this phase.”

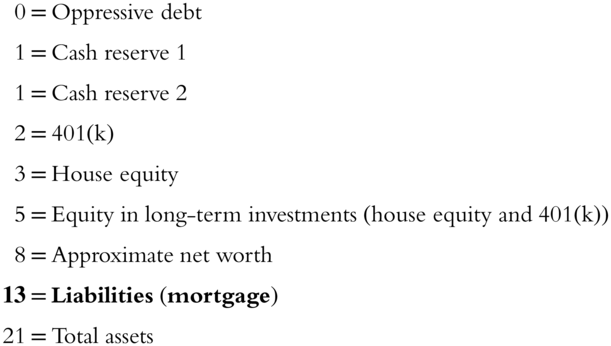

The number 8 is a Fibonacci number, but let's look at what is happening. Let's assume that you embrace the glide path outlined in the Independence phase.

The problem that you are facing is that your long-term assets are a 5 and liabilities are a 13. Assets, of course, could not support your debt, and therefore, you are dependent on income. There is no chance to retire at this time. This creates two goals: You want to have less debt and you want to have more assets.

There are two ways to lower your debt ratio:

- Pay down debt.

- Build up assets.

Path 1 is that you could pay down debt. If you do this, then (1) your rate of return will be equal to your after-tax cost of debt; (2) your investments will grow by the rate of return they earn; and (3) your liquidity will be reduced.

Path 2 is that you could choose to build up assets. I assert that the debt ratio should be reduced by building up assets and harnessing the long-term power of compound interest.

From 13 to 8

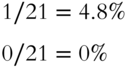

From the example in Chapters 3 and 4, Brandon and Teresa had a mortgage of $195,000, or 13. Their total assets were $300,000, or 20. In the Fibonacci sequence, 13/21 implies a debt ratio of 61.9 percent. At the end of the Independence phase, Brandon and Teresa's debt ratio is $195,000 / $300,000 (or 13/20), which is 65 percent. I think most people can comfortably agree that long term this is too high; they have too much debt. The question we are analyzing is if they should reduce debt by paying down debt or by building up assets.

To do this, I need their debt to be a lower number in the Fibonacci sequence. I need it to move from 13 to 8. This is why debt is the center of this phase and why 8 is the basic unit of measurement.

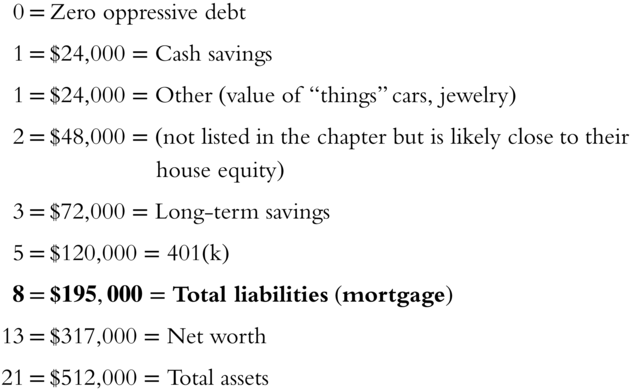

From Chapter 4, “Therefore, Brandon and Teresa would divide 195,000 by 8, which would give them a base unit of 24,375. Now while you may choose to be that precise, I prefer to round it to 24,000. You could also round it to 25,000.”

Table A.4 is a reprint of Table 3.3 from Chapter 4. Here you can see the series: 0, 1, 1, 3, 8, 13, 21: all Fibonacci numbers but with debt moving from 13 to 8.

Table A.4 A Blank Freedom Phase Worksheet—Debt Based

| Goal/Bucket | Formula | A Balanced Path | Where You Are | Gap |

| No oppressive debt (No debt at a rate over 10 percent) | 0 | $0 | ||

| Cash reserve, checking + savings | Base unit × 1 | |||

| Other (jewelry, cars, furniture) | Base unit × 1 | |||

| Long-term investments (after-tax) | Base unit × 3 | |||

| Retirement savings | Base unit × 5 | |||

| Total debt (mortgage) | Base unit × 8 | |||

| Net worth | Base unit × 13 | |||

| Total assets | Base unit × 21 |

For Brandon and Teresa, their debt ratio falls to 8/21, or 38.1 percent. Here is how their life looked in the chapter:

Their debt ratio is falling considerably, even though they have not paid down any debt! Importantly, they now have a significant level of assets that are working for them long term. They have just materially increased the chances that they will be on track for retirement.1

Later in the chapter, I show an income approach to the Freedom phase. The goals are laid out in monthly income goals of 0, 5, 5, 15, 25, 40, 65, 105. If you use a basic unit of five months' income, the series becomes 0, 1, 1, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21. In both approaches, the ending debt ratio is 8/21, which is 38.1 percent.

This phase will likely take a decade of time, and during that time many life events, good and bad, are likely to happen. Therefore, as the scale grows, it increasingly becomes important to look at this as a glide path more than to force a fit.

From 8 to 5

In Phase 4: Equilibrium, we continued the assumption of never paying down debt and building up assets, but with a desire to have a lower debt ratio and a desire to be able to pay off the home. Table A.5 is a reprint of Table 4.4 from Chapter 4.

Table A.5 A Blank Equilibrium Worksheet

| Goal/Bucket | Formula | A Balanced Path | Where You Are | Gap |

| No oppressive debt (No debt at a rate over 10 percent) | 0 | $0 | ||

| Approximate cash reserve (checking + savings) | Monthly income × 7 | |||

| Approximate other (jewelry, cars, furniture) | Monthly income × 7 | |||

| Approximate mortgage | Monthly income × 35 | |||

| Approximate long-term investments (after-tax) | Monthly income × 56 | |||

| Approximate retirement savings | Monthly income × 91 | |||

| Approximate total investment assets | Monthly income × 147 |

As listed, the series appears to be 0, 7, 7, 35, 56, 91, 147. If you assign a basic unit of seven months' income, the series can be rewritten: 0, 1, 1, 5, 8, 13, 21. There is balance not only in the assets and liabilities but also in how the assets are weighted relative to each other. From Chapter 4, “Notice the beautiful balance the beacons show us:

The debt ratio is $175,000 / $735,000, or 23.8 percent.

Retirement savings / Total investment assets = $455,000 /$735,000, or 62 percent.

This is approximately the same ratio of after-tax assets as a percentage of retirement assets ($280,000 / $455,000), or 62 percent.”

A fun side note is that while I do not discuss it in Chapter 4, they are eligible for a line of credit against their long-term investments. This strategy is the theme of my first book, The Value of Debt, and is discussed in Appendix C. They could comfortably borrow up to a 2 on their securities-based line of credit (or 14 months' worth of income), which would be 2/8, or a 25-percent debt ratio against their portfolio.

Super Cool Math

As presented, when your investment assets equal 21, then you are nearing the strike zone for retirement. If you assume a 5-percent distribution in retirement then equals 1.05, which means that savings will generate about 7.35 months of your income. This is calculated by taking the base unit of 7 months ![]() months of income. You would need pension, Social Security, and changes in lifestyle to cover the rest. (For a detailed discussion on distribution rates, see The Value of Debt in Retirement.)

months of income. You would need pension, Social Security, and changes in lifestyle to cover the rest. (For a detailed discussion on distribution rates, see The Value of Debt in Retirement.)

If you do not want to depend on Social Security we can turn to another number in the Fibonacci series, 34. When your investment assets equal 34, then ![]() equals 1.7. This is equal to about 12 months of income (

equals 1.7. This is equal to about 12 months of income (![]() ).

).

How long does it take to get to 21 or to 34? It depends on your savings rate, time, and on your rate of return. Table A.6 illustrates what Fibonacci number you can mathematically achieve with different savings rates and different periods of time, holding constant a 6-percent rate of return.

Table A.6 Savings Rate and Years to Get to Various Fibonacci Numbers

| Number of Years | ||||||

| 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | ||

| Savings Rate | 5% | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 10 |

| 10% | 4 | 6 | 9 | 14 | 19 | |

| 15% | 6 | 9 | 14 | 20 | 29 | |

| 20% | 8 | 13 | 19 | 27 | 38 | |

| 25% | 10 | 16 | 24 | 34 | 48 | |

This chart tells you what you intuitively know and what I said earlier in the book: If you save a little, for a short period of time, there is little chance you will be on track for retirement. If you save a lot for a long period of time, your chances increase significantly. Specifically, if you save less than 10 percent of your income, there is little chance you will have enough assets to retire, even counting Social Security and even with a 35-year time horizon of savings.

Of course you could challenge my return assumptions, but return hardly matters! I have held the rate of return at 6 percent. Although that might seem conservative, I am excluding inflation from these assumptions. Inflation plus 6 percent is difficult to achieve for any investor (see Chapter 5 discussion on returns relative to inflation). But let's play with it a little. Even if you have a rate of return of inflation plus 8 percent, there are no savings rates below 10 percent that will let you get to 21 in less than 30 years.

I can go on: Inflation plus 10 percent, a vastly unreasonable assumption, would still require a 10-percent savings rate and a time horizon of 25+ years to get to 21. Bottom line: If you are saving less than 10 percent, you need to wake up now. You are not on track and you cannot make it up with return.

However, if you save 15 percent to 20 percent, then even at an inflation plus a 4-percent rate of return, you should be in a good zone in 30 to 35 years. If your returns are higher, you could potentially retire earlier. If you think returns will be lower, say inflation plus 2 percent, then you need a savings rate greater than 20 percent and a time horizon longer than 35 years.

And herein lies the proof to the alternate hypothesis and to the strategy outlined in the book. If you embrace the glide path outlined in the book, the investment ideas highlighted in Chapter 5, combined with a 15 to 20 percent savings rate for 35 to 40 years, then I am approximately 95 percent confident that you will be able to retire comfortably. The higher the savings rate and the longer the period of time, the greater my belief that the glide path as presented will lead to a comfortable retirement.

If you follow conventional wisdom, the null hypothesis, and first pay off your debt, then holding the other assumptions constant, I am less than 5 percent confident in your ability to replace your income in retirement in the same amount of time. In fact, my math simply shows it isn't possible for most people to adhere to conventional wisdom to pay off their debt, have a less than 20-percent savings rate, and retire in less than 35 years.

Therefore, I conclude that debt adds value in building wealth. More specifically, if you choose to use good debt, working debt like a low-cost mortgage—especially one at generational lows, like in the year 2016—then not directing your precious savings to pay down low-cost debt is when debt is most valuable. It is my opinion that yes, our anti-debt hysteria is massively contributing to the savings crisis in America and that a thoughtful, balanced approach is significantly better.

But here is perhaps my most powerful math: The above is assuming that you are starting from zero! It is true that about 50 percent of Americans have less than $400 in savings, but by virtue of the fact that you are reading this book, there is a good chance you have more than $400 saved up.2 If you are in that category, then even if you are behind, you can 100 percent get on track.

Remember how at the end of the Launch phase there was a base of retirement savings? If you can clear this phase by the time you are 40 and save at a rate of 15 percent, then you should be on track to have more than 21 within 25 to 30 years; yes—if you start today you can still be on track!

Much of America is significantly behind in retirement savings. If this is you, then you need to:

- Immediately focus on building up assets.

- Target at least a 15-percent savings rate.

- Understand that you need a 20+ year horizon of saving at that level.

- Do not pay down debt that has a cost less than your estimated (or required) return.

Given even a relatively small starting base, a mid-level range of savings, and 20 to 25 years, then there is a high chance of being able to be on track for the retirement you have dreamed of.

If your net worth is less than 12 times your annual income, you have a debt to your future self and need to keep the focus on building assets. For the fortunate few, if your net worth grows beyond 30 times your income, or approximately equal to a Fibonacci score of 55 in the above tables, while you may choose to embrace the strategic benefits of debt, you generally do not need debt.

Please visit the website valueofdebt.com to learn more about how the L.I.F.E. phases are inspired by and tie to the Fibonacci sequence.3