Appendix C

Home Purchase and Financing Considerations

Hopefully, I made it clear throughout the book that it is my opinion that too many people are too focused on home ownership too early in their life. Home ownership is a big topic during our 30s, 40s, and 50s—and it is an important topic. I am neither for or against renting, buying, fixed rates, floating rates, long amortization schedules, and short amortization schedules. Like many things in life, (1) the answer depends on your specific situation; and (2) so often I see people doing the opposite of what might be optimal. The following should be considered to be my personal opinions that are designed to help the debate around your kitchen table.

Before we dive in, if you are interested in this topic I would encourage you to turn to the Resource Guide, where I provide a list of videos with education and calculators on the following topics:

- Renting vs. Buying

- How Much Home You Can Afford

- Introduction to Mortgages

- Understanding Alternative Mortgage Options

- Adjustable Rate Mortgages

- Fixed vs. Adjustable Rate Mortgages

Being familiar with these resources will help your understanding of my perspective.

Don't Rush to Buy a House

Especially when you're young, think twice before you purchase a home. This advice isn't always popular because it goes against the American Dream. We've been taught that home ownership is the first step to financial security and stability. But owning a home comes with many hidden costs, and unless you stay in a home for at least three years—ideally, five to seven years or more—the math on this investment doesn't pencil out.

When you purchase a home, you need to be prepared to cover the following expenses:

-

Depreciation/maintenance: A house will depreciate by approximately 2 percent to 3 percent of the building's value, excluding the land, per year. If the physical building of your home is worth $500,000, it's reasonable to assume that you will spend somewhere between $10,000 and $15,000 a year just to keep the building in the same condition.

New construction is a bit tricky. You might perceive that there aren't as many maintenance issues—which is often true—yet many times there are a lot of finishing touches that need to be done: curtains/window treatments, landscaping, decorating, electronics, paint, and so on. After the tenth year, pretty much everything that plugs in is in danger of retiring. Carpets, potentially the roof, and certainly the paint will also need replacement (not to mention, the entire decorating scheme will be outdated). After 20 years, maintenance costs may normalize in the 2 percent to 3 percent range, but that could mean $5,000 in windows one year and a $20,000 driveway the next. If you are in a condominium or association, you may see some of this deprecation expense reflected in your dues.

These all need to factor in to your budget. Importantly, while the expenses of depreciation might not be immediate, you need to be setting aside the money early: setting aside $700 per year for the roof that needs to be replaced in 20 years instead of having a $14,000 surprise bill. From my experience, new house or old house, you should anticipate 2 percent to 3 percent of the building value in expenses.

- Property taxes: Although they range across markets, these will generally be between 1 percent and 2 percent of the property's value, depending on where you live.

- Closing costs and upfront transaction costs: These range by area but are generally between 1 percent and 2 percent of the property's value, and many markets now have mansion taxes and/or mortgage taxes on mortgages over a certain size.

- Selling costs: When you close on a property, unless you're very lucky, it's likely that you paid the highest price for that property at that point in time. If you turned around and resold the property immediately, you would have a 5-percent to 6-percent real estate commission, and you would probably have to sell it for 2 percent to 3 percent less than you paid for it. It is possible you would take a 7 percent to 9 percent hit.

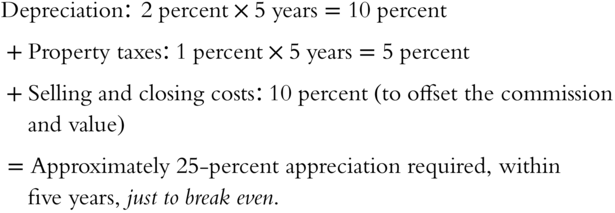

Despite all this, many people still feel like they're wasting money on rent. Like most things, this can be quantified. Adding the above expenses together, I estimate that if you are in a property for five years, you need to offset the following expenses:

Generally, the longer the time period, and the more you believe in appreciation, the more the formula shifts toward buying; the shorter the time period, the more it shifts toward renting.

When Home Ownership Can Go Wrong

Imagine a couple, Patrick and Emily, who just moved into their new $500,000 home with a $400,000 mortgage. Shortly after the move, 2008 repeats. Their house falls in value by 20 percent. Patrick and Emily's house is worth $400,000, but they would likely net $380,000 after sales commissions if they sold it. Not only is their home equity wiped out, but also they would have to bring money to the closing table to get out of their home. At the same time, the market is crashing so their portfolio falls by 30 percent. Adding insult to injury, Patrick loses his job. Then to top it off, the home needs a major repair. This will undoubtedly be a stressful situation.

Too often, people are surprised when things like this happen. It should not be a surprise: When the economy turns south, which will happen, it is easy to envision an environment where housing prices are going down in value, stock market prices are going down in value, and unemployment is going up. At the same time, homes do need repairs, and oftentimes you cannot control the timing of those repairs.

Renting protects your liquidity. You don't have to tie up assets! Renting is a form of insurance. It protects you from a wide range of outcomes. It is much easier to get out of a lease than it is to get out of a house in a down market. You should always quantify the cost of renting versus buying to determine how much this insurance costs. In markets where renting is less expensive than buying, this insurance is free! In other markets, renting is much more expensive than buying, but the cost of your insurance is dependent on the price of the property you buy.

Let's say that Patrick and Emily could have rented their house for $2,500 per month. They certainly would have felt like they were “wasting” $2,500 per month—but would they be? At 5-percent interest for the full purchase price of $500,000, Patrick and Emily's annual interest expense would be $25,000. In addition, the property taxes might be around $7,000 and the property likely has about $4,000 per year of maintenance expenses. The total expenses of owning the property are about $36,000 per year, or $3,000 per month. Granted, they could be missing out on some tax benefits and some potential appreciation, but they would have a lot more flexibility with a rental. In many cases, the tax benefits might not be as great as you think and while properties can go up in value, they also can go down in value.1

Save Yourself the Anguish

Home ownership brings many risks, from price variations to natural disasters, and requires upfront transaction costs as well as cash for major repairs and maintenance. During the critical early years of your financial life, you're better off building up cash reserves and your investment portfolio. With those in place, you'll have many more options and a lot more flexibility when the time is right to invest in a home.

Be Careful!

Most people don't buy a house for a price but instead buy a monthly payment. This has significant implications on the value of the underlying asset. If you can afford a $1.2 million house with a loan at 5 percent, what happens if interest rates rise to, say, 8 percent? All things equal you could afford to buy a home worth about $750,000. This is a stunning change in value.3

You likely believe that, given enough time, housing prices go up. Most people do because of our tendency to extrapolate recent trends into the future. I worry most people oversimplify. We need to look at what happened with growth in the 1960s, inflation in the 1970s, and declining interest rates from 1980 through 2015. Housing prices did well in each environment. People look at this data and conclude that houses must be a good investment, but I'm not certain this is the case.

While it is possible that housing prices could grow with inflation, it is, of course, possible that they could grow by less than inflation or even go down—potentially a lot—in value. This is especially risky if interest rates are starting at generational lows. In Japan, even with interest rates at generational lows, house prices today are approximately where they were in 1985.4 This type of data should influence rent-versus-buy decisions.

All Mortgages Are Not Created Equal

Most Americans first encounter working debt through mortgages. And even though they'll live in their primary homes for a median duration of only 5.9 years, they'll pay to lock in interest rates on those mortgages for 30 years. This is silly.5 Yes, they have the security of knowing they've locked in rates for decades, but they're paying to ensure that their interest rates don't change for a good 20 years longer than they're likely to keep the home. Why would anyone pay to lock in a 4 percent rate for 30 years when they're likely to sell the home and pay off the mortgage in less than 10?

Unless you know that you're going to hang onto a home forever, a five- or seven-year interest-only adjustable-rate mortgage could make a lot more sense. On a $1 million home, you could pay as much as $10,000 less per year in interest than you would with a 30-year fixed-rate product. That extra money can be invested so that it's working for you but available should you need liquidity. (Note that taking on interest-only payments because it's the only way to buy a house you can't afford is highly likely to land you in financial distress.)

Before you even begin talking to a real estate agent, make sure you understand all your options.

One-Month LIBOR Interest-Only Floating Rate ARM

Interest rates for this product are adjusted monthly based on a rate such as LIBOR, one of the most common benchmark interest rate indexes used to make adjustments to adjustable-rate mortgages. Most of these products are LIBOR plus 2 percent, which in today's environment is roughly 2.5 percent. So if you borrow $1,000,000, your fully tax-deductible interest payments would be a little more than $2,000 per month—and that payment is reduced every time you pay down principal.

Most floating-rate products are capped at 10 to 12 percent, so your rates can't skyrocket to 20 percent—which is good—but they could spike to, say, 6 percent in a couple of years, and they could go as high as the interest rate cap. It's important to self-insure when using this option. If you use one of these products, I recommend that you live your life as if you needed to make a payment equal to a 30-year fixed amortizing loan and put the additional money into your portfolio—where you might be able to capture the spread and make more money on it. That way you not only are used to making the higher payments, but also have a reserve to pay down the mortgage if you run into a high-rate situation.

5-, 7-, 10-Year Interest-Only ARM

The benefit to adjustable-rate mortgages is that you can lock in an interest rate for a set amount of time. When you take on a 5/1 interest-only loan, generally you lock in a rate somewhere between a one-month LIBOR and a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage (assuming a “normal” yield curve). The low interest rate is locked for five years, and then—depending on the details of your loan—it becomes an amortizing loan.

The beauty of this is that during the first 5, 7, or 10 years of the loan, you have the option to pay only the interest every month or also pay down principal, which puts you in the driver's seat. If you think you'll be in a home for 7 years or less, this is an excellent option—but you should self-insure by putting the amount you would pay on the principal into your portfolio, where it can be making money for you but is available if for any reason you choose to pay off the debt.

15- and 30-Year Fixed Rate

I rarely believe in 15-year fixed-rate mortgages. I think they're a trap. Many people are lured in by rates as low as 2.5 percent for this product, but guess what? They owe thousands of dollars in mandatory payments every month—no matter what happens. CFOs would never sign up for that. When you're young and accumulating wealth, it makes more sense to take on an interest-only or even a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage and invest the savings so that they can compound during your “go” years. If your savings rate is over 20 percent, then I do think that a 15-year mortgage can be a very powerful piece of your financial picture—assuming you can make the mortgage payments and keep saving at the 20-percent rate. If your savings rate is below 20 percent then I cannot get the math to come out in any way that shows that you can afford to be in a 15-year fixed mortgage.

A 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is a different animal. If you believe you will live in the house you're buying for a long, long time and are worried about rising interest rates, this is a good option. The risk, of course, is that you're paying a lot of money to “insure” an interest rate for 30 years. If you stay in the home for less than seven years, it might not be worth it. However, with interest rates at generational lows, the incremental cost of the insurance is relatively low, and this could turn out to be a great time to have locked in low-cost debt. See the Resource Guide for more information about interest rates and inflation.

First Bank of Mom and Dad—Part 2

I shared ideas about the First Bank of Mom and Dad in Appendix B. If your parents have a sizable investment portfolio and are willing to help you get into a house, they could consider using their securities-based line of credit to help you. Let's say you have a decent income, but you live in Chicago, where rent for a two-bedroom apartment with parking is $4,000 a month. That rent isn't tax deductible, and due to high income you could potentially benefit from deductions. How will you ever get ahead when you're paying $48,000 a year just in rent? If you're in the 25-percent tax bracket, you have to generate $64,000 a year in income just to pay the rent. That's ridiculous. How the heck can you save for a down payment while you're paying $4,000 a month in rent?

Assuming you need to come up with a down payment of 20 percent, or $100,000, you can ask your parents to pledge $300,000 in taxable securities from their portfolio and take out a securities-based loan using the securities as collateral. Your parents' money remains invested—though not accessible—and you can pay only the interest on the loan until you've saved up enough to pay it off. Your parents are on the hook for the pledge, but they're not taking on the full responsibility of cosigning a loan.

You could buy a $500,000 apartment, put down $100,000, and put $400,000 on a mortgage. Your monthly payment might be $3,000 (including taxes and homeowners association fees), but you might receive about $1,000 of tax benefits, for a net cost of about $2,000 a month.6

First-Time Home Buyers, Low- and No-Down-Payment Mortgage Options

There are numerous programs that enable low- and no-down-payment options. Some of these are offered by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States Department of Agriculture, and the FHA (Federal Housing Administration). Other programs are available through Private Mortgage Insurance, also known as PMI. Further, some online entrants into lending are offering lower down payment options without PMI for borrowers that fit certain criteria. It is outside of the scope of this book to discuss the eligibility, pros, and cons of each program. However, if you are set on purchasing a home these alternatives are well worth researching or visiting with a professional for their advice.

With respect to the L.I.F.E. path and how these solutions relate to the concepts in this book, if you follow the glide path outlined in the book, these can be wonderful solutions if:

- You have cleared the Launch phase.

- You have completed or have almost completed the Independence phase.

- You expect the following to be true:

- You will be in the property for more than five years.

- Property values are low and are more likely to appreciate than depreciate over the next five years.

Look back at Brandon and Teresa. If they could buy their home with $25,000 down at the same mortgage interest rate, then it could be wonderful for them. They would have more money invested for a longer period of time and they would have more liquidity and more flexibility. If you are in this camp and can check off on the three points just listed, I strongly recommend that you learn more about the power of low-down-payment mortgage options.

Owning Can Be Great

All of this material can make it sound like I'm against home ownership, which is not at all the case. The examples of homeownership being a disaster in my personal life and during the crisis are vast—but I do think it is important to share three short examples of ownership success.

A dear friend bought a home in a Midwest town 15 years ago—when she was about 27 years old—for about $150,000. She is handy and has done some nice improvements. The home is likely worth about $240,000, and her mortgage is down to $75,000. She refinanced her mortgage onto a 15-year fixed at 2.5 percent. Her mortgage payment is $500 per month and she is on track to own her home by the time she is 57, but may pay it off earlier. She also has a great pension and is a wonderful saver. She has built up a very impressive retirement savings account. She has a nice balance in her checking and savings account. I could nitpick the fact that she has limited liquid investable assets (she can't have a securities-based line of credit), and she has a 15-year amortizing loan—but that would be absurd! She can afford the 15-year amortizing loan, and she is on track. Is she doing something wrong? Heck no! She is amazing!

A couple I know was in their mid-thirties in 2011 and bought a little more house than the L.I.F.E. guidelines would suggest. They did so taking advantage of a low-down-payment mortgage. This risky combination so far has turned out to be a good decision. Due to the growing family, the larger house likely prevented a move they might have otherwise made by now. Further, their timing was great and (at least to now) the house has appreciated considerably.

A third friend—a dual-income couple—moved across the country for a job. They had two young children and had been renting from college through age 35. In the market they moved to, the rent-versus-buy math was very much in favor of buying. Like professional surfers, they rode the waves perfectly. The math in their former market suggested rent, which they did, and avoided the housing crisis during a time where their affairs were more fragile. The math in their new market suggested buy, which they did in the years immediately following the crisis and when they were at a more stable time in their personal life.

At the end of the day, this is the custom suit business. Combine the thoughts in this chapter, with the glide paths in the book, the market environment in your community, and the tools in the Resource Guide, and hopefully you can feel a bit more empowered with the decisions you make!7