5

Operationalize Phase

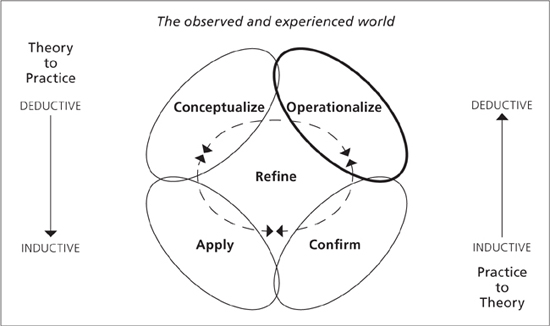

TO OPERATIONALIZE A THEORY, the theory must be expressed in terms of its functional use for the purpose of acceptance or rejection. The Operationalize phase becomes a logical bridge between the Conceptualize and Confirm phases, but it also interplays with the Apply and Refine phases (Figure 5.1).

The purpose of this chapter is to describe specific approaches to operationalization that serve as an instructive guide. This chapter will

• define the Operationalize phase,

• describe the general inputs to this phase,

• provide a practical summary of Operationalize phase activity,

• describe the outputs of the Operationalize phase, and

• propose a set of quality indicators for Operationalize phase effort.

WHAT IS OPERATIONALIZATION?

An applied discipline theory needs to be confirmed or tested in its real-world context so as to establish its utility (Lynham, 2002a). The explanation that the new theorizing creates must be examined and assessed in the world in which it occurs. To confirm a theory, the ideas and relationships must be converted to observable and confirmable components or elements (Lynham, 2002a). Operationalizing theories commonly results in hypotheses, empirical indicators and other claims (Cohen, 1989), which are investigated in the confirm phase. Ultimately, operationalizing requires that the theorist develop strategies for judging the accuracy and fit of the new theory in the world in which it is expected to function.

FIGURE 5.1 Operationalize Phase of Theory Building in Applied Disciplines

The Operationalize phase requires connecting the theoretical framework and the world of practice. The ideas of being translated, or converted, to observable components/elements and to be confirmed in the world describe the core task of operationalization and its connection to later phases in theory building, especially the Confirm phase.

To operationalize, therefore, refers to how the concepts or units involved in a theory and the associated relationships are going to be confirmed or measured. The idea of operationalization developed from the work of Bridgman (1922, 1927) and Bentley (1954), who argued that concepts must be made measureable in order to make statements about their accuracy.

In the social sciences, the concept of operationalization usually becomes part of the assessment method and is clearly evident in psychometric evaluation. For example, investigators may wish to measure happiness. But a given participant’s degree of happiness is intangible and cannot be directly measured. So investigators might operationalize the concept to include tone of voice, facial expressions, gestures, and word choice, among other indicators. However, alternative philosophical orientations require tools other than the scientific method to establish how a proposed explanation will be confirmed empirically.

Scales, instruments, and inventories are forms of operationalization and are clearly identified in excellent research reports. Some strands of qualitative inquiry also make use of the operationalization concept by stating how research results can be assessed. This is why some qualitative approaches employ hypotheses. Other forms of qualitative inquiry, such as phenomenology, generally do not make use of measurement and specifically avoid stating measurement criteria. However, some authors have attempted to use measurement principles even in phenomenological research, though these efforts are rare. For example, one study of hypnosis used a self-report instrument, the Phenomenology of Consciousness Inventory, to quantify the experience of hypnosis (Venkateash, Raju, Shivani, Tompkins, & Meti, 1997).

INPUTS TO THE OPERATIONALIZE PHASE

The outputs from the Conceptualize phase can be direct inputs to the Operationalize phase. That is, a carefully constructed model, system, or set of linked concepts is the basis for operationalization. Plain and simple, a theorist must have a working set of ideas that explain human and system behavior to engage in translating or converting them into confirmable measures. It is also reasonable for theory investigators to speculate about operationalization components as they get clarified through the various phases. This may sound a bit sloppy, but the human mind and the reality of implementation opportunities can have the theory-building phases functioning simultaneously or in various sequences. Keeping careful documentation is essential for responsible reporting.

Several of our theory-building projects have spread over many years. One of the efforts focused on performance improvement in business, industry, and organizational contexts. The core model for a theory of performance improvement included the requirement to call upon and fuse contributions from psychological, economic, and system theories into a holistic model and theory of performance for organizations and human-made systems. It is graphically portrayed as a three-legged stool. It was a deep discussion with a graduate student about unethical operational business dealings and his desire to add a fourth “ethics” leg to the conceptualization that led to a revision. Having grown up in a business family with impeccable honesty and ethics, we had built-in blinders about ethics at the conceptualization phase. The void of operational links related to ethics in the performance became a shock once it was revealed. The operational review resulted in the addition of an ethical “rug” for the conceptual performance stool to stand on (Figure 5.2). It is interesting to note that the subsequent massive ethical failures on the part of Wall Street could have been predicted, and in some cases squelched, if the revised performance theory had been applied.

FIGURE 5.2 Theoretical Foundations of Performance Improvement

Theoretical Foundations of Performance Improvement

Source: Swanson (2007b).

APPROACHES TO OPERATIONALIZING THEORIES

There are distinct approaches to theory operationalization, and three core approaches are presented here to illustrate variation. Aligning with key research strategies that were first noted in Chapter 2, these approaches are (1) the quantitative approach, (2) the qualitative approach and, (3) the mixed methods approach.

An important point when it comes to operationalization is that the approaches are more discreet. It can be difficult to combine operationalization strategies into a mixed methods approach when considering their philosophical assumptions. The key is to fall back and continuously revisit the purpose and intended outcome of the theory-building effort. Is the theory intended to explain a phenomenon and how it works? Is the theory going after anomalies to already established theories, or is it an entirely new effort at describing novel phenomenon?

Another driver here is the type of theory. Grand theories by definition will have far and wide boundaries. Generalizability is desirable for these theories, and a quantitative approach may be best suited to the task. Local theories have a much smaller domain of application, and the purpose is not prediction or generalization. In such cases the theorist may only need to establish propositions. Midrange theories will be a philosophical no man’s land, in which the purpose of the theory-building effort is even more important. In midrange theory building, the theorist must clarify and describe how potentially competing assumptions were resolved. For example, case studies and grounded theory studies may work best when both quantitative and qualitative approaches are used. Remember, grounded theory uses data to generate propositions and does not actually require that they be formally tested. The General Method of Theory Building in Applied Disciplines being presented here does require formal confirmation. Again, decisions here must be connected to the initial purpose for building the theory and its intended use, with an ultimate goal of assessing its fit with the real world. In summary, we have found two critical drivers of theory-building processes: (1) the purpose of the theory building and (2) the boundary of the theory.

Suppose we were to operationalize the effects of sending flowers to recovering patients with a goal of increasing health. The core question is how we would measure the proposed increasing health of patients. This could be operationalized into a number of variables such as shorter hospital stays (as measured by number of days spent in the hospital), heart rates and blood pressure (as measured by beats per minute and diastolic and systolic pressures), and increased morale (as measured by a series of questions asking about attitude, outlook, and emotions). One of these is not like the others.

The measurement of morale has a different set of indicators from hospital stays, heart rates, and blood pressure. Time, quantity, and quality are three appropriate measures when thinking about operationalization. While quality measures such as reports of morale do not necessarily fit into quantifiable boxes, a theorist would still have expectations for what patients might report. Increases or improvements in attitudes, outlook, and emotion can be described. For operationalization, the challenge would be to describe what those increases or improvements might include and how we would know if expectations were not met—and would artificial flowers have the same effects?

(Example based on Weinir, 2011)

Quantitative Approach

The quantitative approach to operationalization will be familiar to many. Probably the most common approach to operationalizing theories involves the use of propositions, empirical indicators, and hypotheses. Because of its adherence to the traditional quantitative assumptions and strategies, Dubin’s (1978) steps 5, 6, and 7 are presented as a comprehensive example of the quantitative approach to operationalizing theories.

The outcomes of the Operationalize phase are “confirmable propositions, hypotheses, empirical indicators, and knowledge claims” (Lynham, 2002a, p. 232). The quantitative view of operationalizing theories specifically includes propositions, empirical indicators, and hypotheses as the remaining steps in Dubin’s theory-building process.

Propositions. Propositions introduce the idea of prediction into the theory building equation. “A proposition may be defined as a truth statement about a [theory] when the [theory] is fully specified in its units, laws of interaction, boundary, and system states” (Dubin, 1978, p. 160). For our purposes, Dubin’s contribution can be summarized and adjusted slightly to say that a proposition is a truth statement about the theory when the concepts have been defined, organized, and bounded—essentially the natural consequence to what the conceptual development phase would produce.

The term logical consequence is a good substitute for the term truth statement (Dubin, 1978). The important point in specifying propositions is to continue the clear logical path set up by the theory builder from the start. Thus, the use of the term logical consequence, truth statement, or proposition is simply to establish the consistency of the theory builder’s logic.

“Quite simply, the use of the [theory] is to generate predictions or to make truth statements about the [theory] in operation” (Dubin, 1978, p. 163). As a result, propositions are prediction statements because they state what will be true having completed the work of the conceptual development phase.

Empirical Indicators. An empirical indicator is “an operation employed by a researcher to secure measurements of values on a unit” (Dubin, 1978, p. 182). Empirical indicators are measurements using some kind of instrument. Operationism, drawing on the work of Bridgman (1922, 1927) and Bentley (1954), highlights the focus on setting up empirical tests for the propositions. For Dubin, operationism referred specifically to the empirical testing of propositions.

Empirical indicators must produce reliable results or, more specifically, values that do not differ from observer to observer. The phrase “as measured by” (such as “the value of unit A as measured by . . .”) is commonly used to describe the empirical indicator used in subsequent research.

There are two types of empirical indicators, absolute and relative. Absolute indicators are “absolute in the sense that there can be no question as to what they measure” (Dubin, 1978, p. 193). Race and gender are examples of absolute indicators. Relative indicators are indicators that “may be employed as empirical indicators of several different theoretical concepts” (Dubin, 1978, p. 195). Relative indicators are often concepts that can be described in relative degrees, such as happiness, satisfaction, or level of difficulty.

Hypotheses. Hypotheses are “the predictions about values of units of a theory in which empirical indicators are employed for the named units in each proposition” (Dubin1978, p. 206). Hypotheses establish the link between the empirical world and the theory that has been under construction. Researchers often state hypotheses without supplying the scientific path to that hypothesis, which sometimes gives the impression that hypotheses are constructed on an ad hoc basis. Ideally, hypotheses should not be ad hoc at all; rather, they are “predictions of the values on units that are derivable from a proposition about a theoretical model” (p. 206).

Each proposition has the possibility of being converted into many hypotheses. “The general rule is that a new hypothesis is established each time a different empirical indicator is employed” (Dubin, 1978, p. 209). As the number of propositions increases, so does the number of possible hypotheses. Ultimately, the question of number of hypotheses is a question of research preferences and energy posed to a discipline and its researchers.

Qualitative Approach

Qualitative approaches to operationalizing theories demand alternatives to hypothesis testing. Generalizability is not always the goal of theorizing. Many qualitative researchers substitute the term transferability for generalizability. While generalizability is a characteristic of the theory itself, transferability refers to the consumer’s ability to use and “transfer” portions of the theorizing to his or her context and situation. A broad approach to operationalizing theories is therefore useful in qualitative methods in theory building. Such methods can include grounded theory, social construction, phenomenology, and some case studies, among others. While we have simplified this discussion by categorizing all of these in the qualitative domain, it is important to note that each specific method may have distinct theoretical assumptions.

The Theory of Symptom Management arranges the major concepts—person, symptom experience, symptom management strategies, and symptom status outcomes—in an interrelated, integrated system (Humphreys et al., 2008). The operationalized theory describes how the parts are related and suggests strategies for using the theory in nursing practice. From a theory phase attainment standpoint, the authors describe that the confirmation of the theory is still in process and that the symptom experience component is the most frequently studied part of the theory.

Recent studies have operationalized this component of the theory into “self-perceptions of causation of depression” (Heilemann, Coffey-Love, & Frutos, 2004, p. 25), battered women’s symptom experiences (Humphreys, 2003), and the impact of sleep on symptom experiences (Humphreys & Lee, 2005). In these cases, the key was to operationalize the theory into measurable outcomes. In the study on depression, the research was self-perceptions and the paradigm was qualitative. Thus, descriptions of patient experiences were examined for common themes. In the study of battered women, the instances of partner abuse were counted; and in the study on sleep, patients recorded the number of hours slept each night over a period of time. These examples show that a subcomponent of a theory can be operationalized and studied in different and complementary ways. All three of these studies showed evidence that confirms the symptom experience component of the Theory of Symptom Management.

Falsifiability is presented as the core alternative to traditional hypothesis testing and can suit qualitative approaches to theory building. Early criticisms of postpositivism resulted in the notion of falsifiability (Popper, 1972). Falsifiability refers to the possibility that a given hypothesis or theory could be shown as inaccurate. The classic example used to illustrate falsifiability is the statement that “all swans are white.” This statement is falsifiable because it is possible that a nonwhite swan could be found. The essence of falsifiability is to search for cases in which the theory does not operate as expected—the black swan. So falsifiability is unique because instead of looking for empirical evidence to confirm the adequacy of a theory, it looks to show its inadequacy. Statements must be falsifiable in order to be testable. Take, for example, the statement “that flower is beautiful”—it is not a falsifiable statement because it is impossible to assess technically.

Popper (1933) explored two kinds of statements that are useful in considering knowledge with regard to falsifiability: observational and categorical. Observational statements simply report the existence of things (e.g., there is a black cat). Categorical statements aim to categorize all instances of a thing (e.g., all cats are black). Few observations are required in the case of cats to conclude that not all cats are black.

In complex organizations and human activity, observational research can be difficult to set up, control, analyze and replicate. Team building is a good example. Tuckman (1965) theorized that all teams must form, storm, norm, and perform. The traditional approach would be to investigate these phases in numerous teams, collecting evidence that supports a hypothesis with a goal of showing that all teams transition through these phases. The falsifiability approach would seek cases of teams that do not show evidence of all four phases and investigate why. Any instance in which a team did not show evidence of all four phases would be enough to disprove Tuckman’s theorizing. Philosophers of science continue to debate how and under what circumstances it is appropriate to move from observational to categorical statements. Pragmatic logic, versus arcane philosophical angst, should rule the decisions.

The job of the theorist when using a falsifiability approach to operationalization is to describe how it will be clear that an instance of human activity does not meet its expected outcomes. An elegant summary of falsifiability is in a quote attributed to Einstein: “No amount of experimentation can ever prove me right and a single experiment can prove me wrong” (Calaprice, 2005). The utility of falsifiability is then in its opposite approach to using data for support of hypotheses. Falsifiability can, but is not required to, develop propositions and empirical indicators—stopping short of hypotheses, in some cases. Again, the natural outcomes and indicators of how it can be known that the theory fits or does not fit the events are sought.

Falsifiability emerged in part as a reaction to the scientific method and attempted to identify its limitations. The greatest utility of falsifiability as an approach to operationalization is in local theories that may not include hypotheses at all. For example, in the social construction orientation, theories are intended to describe, so hypotheses may or may not be used. In the case they are not, falsifiability gives the theorist a way to indicate how the adequacy of the description is to be judged. Using falsifiability as an operationalization strategy gives the theorist more freedom to describe criteria for assessing the theory’s accuracy than the stepped approach described earlier. Falsifiability is more appropriate for local theories and cases in which the theorist does not seek to generalize findings to other domains. However, it is also vague—the details of “how” is missing, and theorists are free to develop falsifiability criteria as they wish. We have positioned falsifiability as a qualitative approach as the decision to reject a theory because it has been falsified requires a judgment based on values. The value-laden-ness of the judgment makes falsifiability a qualitative approach.

Mixed Methods Approaches

Most often, mixed methods include case study and grounded theory approaches to theory building. These approaches use a variety of methods to address the theory and research purposes defined from the start. Grounded theory and case study theory-building projects are almost always midrange theories. In other words, mixed methods approaches to theory building are often intended to produce theories that are generalizable to similar contexts and situations.

Some theorists have argued that mixed methods pose philosophical challenges—specifically, that it is difficult or impossible to hold opposing assumptions about the nature of reality at the same time (Swanson & Holton, 2005). While reconciling the complexities of mixed methods theory building is difficult, the results are often among the most useful in applied disciplines (Gioia & Pitre, 1990). Grounded and case study theory building have high utility in organizational research because they live in the domain of midrange theories. They are not intended to predict or produce universal laws. And they go beyond single instances of human activity. Brief descriptions of grounded and case study theory-building frameworks are presented as a basic structure for these kinds of projects.

Grounded Theory. The general steps of grounded theory building include (1) initiate research, (2) select data, (3) initiate data collection, (4) analyze data, and (5) conclude the research (Egan, 2002). On the surface, this process is quite linear. Yet, a core feature of grounded theory is that all things are integrated at all times in the search of patterns—always integrating and always in motion (Glaser, 1992). For sure, once a realm or domain is brought into focus, the act of operationalizing actually gets carried out by analyzing the data obtained from observation. The ongoing data collection observations are the basis for analysis and theory generation. It is when the saturation of data is such that the theorist moves on to fully document the final theory, including operationalization and the other four phases of conceptualization, confirmation, application, and refinement.

Case Studies. The general elements of the case study approach to theory building are to (1) determine the research questions, (2) select the case(s) and data-gathering and analysis techniques, (3) prepare to collect data, (4) collect data, (5) analyze and evaluate the data, and (6) develop a report (Dooley, 2002). With these generic elements, it is easy to see that the case study approach can accommodate any or multiple specific techniques within its framework.

Case study approaches are wide ranging (Eisenhardt, 1989). The concepts of a case, case study, and case study research are different and often inappropriately used interchangeably (Herling, Weinberger, & Harris, 2000). One major role of cases is to describe the “how” questions. Case study research studies can certainly contribute to the Conceptualize phase of theory building (Eisenhardt, 1989).

Case studies, and the narrative around the cases, can also be very useful in the Operationalize phase. Operationalizing a theory framework by translating or converting it to observable, confirmable components/elements can be aided by detailed case study reports. This goes beyond the higher-level conceptualization. A narrow single-case exploration (not a case study or case study research) could be pursued to clarify propositions.

We work with individuals who are both experts and neophytes in specific realms. Several years ago, one true neophyte we worked with was interested in learning how to synthesize information on a single topic that was coming from various print sources.

Having previously interviewed a diverse group of experts as to their data collection and synthesis strategies, we created a methodology for doing this knowledge work. Groups of moderately experienced subjects followed the new methodology and found it helpful in improving their synthesis of complex information. The new methodology was then tried out by a pure neophyte who agreed to self-report on her effort—no matter how embarrassing. The earlier multiple-expert investigation resulted in recommended note taking for each document to use in wading through the synthesis task. In this single case, the neophyte collected her documents, took her notes, and found herself completely stalled when it came to synthesis. The in-depth interview with the neophyte revealed that the print documents, all written by experts, contain varied technical terminology and jargon. While an expert in a field has a superordinate language to decode these documents, the neophyte had none. Thus, based on this single informative case, the methodology was altered. At the individual document analysis step, the synthesizer was to put their individual documents notes in their own words only—no quotes. With the notes for each document in the neophyte’s own language—a common language across all documents—she and other neophytes were able to intelligently synthesize the knowledge being reported in disparate documents.

THE OPERATIONALIZE PHASE OF THEORY BUILDING

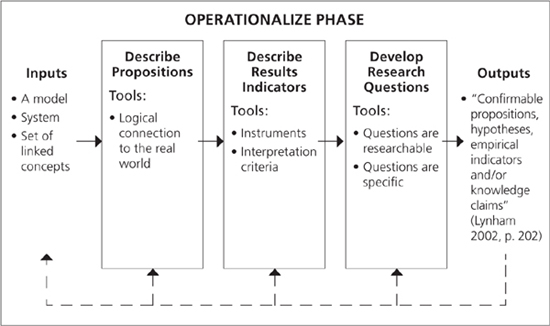

This section presents the integrative Operationalize phase of theory building in applied disciplines. Again, the approach provides a framework within which to use a variety of other tools. The major steps of this phase are to (1) describe the propositions of the theory, (2) describe the results indicators of the theory, and (3) develop the research questions of the theory.

Step 1—Describe the Propositions

For any theory, propositions must be described. The purpose of propositions is simply to extend the theory into the real world by creating statements of its natural outcomes. The propositions identify the expected outcomes, given the construction of the set of concepts. Truth statements, logical consequences, and natural outcomes are all terms that imply the same idea at heart, which is to bring the theory into empirical reality. Propositions are completely appropriate for grounded, case, and social construction orientations toward theory building. Propositions commonly take the form of “if . . . then” statements to connect the set of linked concepts to an outcome. A variety of sample propositions follow:

• If gravity is truly a natural law, then every time an object is released from the air, it will move toward the ground.

• If we increase managers’ pay, then their productivity will increase.

• If employees receive increased structured learning opportunities, then their engagement in the organization will increase.

Propositions can follow the logic of the theorist from the conceptualize phase into the real world by describing the perception and behavior changes that would be required to indicate the theory is working. A useful way to start describing propositions is to take each concept involved in the theory and describe how it changes if the theory logic is accurate. Propositions can also arise from the other phases, which, though connected, do not follow a linear path.

Step 2—Describe the Results Indicators

Results indicators extend propositions by adding the measurement piece. In other words, results indicators introduce the measurement instrument or confirmation criteria into the theory-building process. So the core work of describing results indicators is in becoming familiar with existing evidence or measures of the expected outcomes. In terms of efficiency, theorists should consider searching for, locating, reviewing, and comparing the existing ways of assessing concepts involved in the theory. Library searches and specific databases make this activity relatively efficient. It is completely appropriate for case, grounded, and social construction orientations to involve results indicators, simply describing the logical results if the theorizing is accurate—there is no prediction involved at this point.

The first part of describing results indicators is to become familiar with what measurement strategies already exist. For example, a specific database accessible through most university library systems is called the Mental Measurements Yearbook. The database includes a comprehensive listing of over 2,700 modern measurement scales, tests, and instruments. Many options for measuring concepts can be explored here. However, most of these instruments are intended for measurement based on the quantitative approach to theory building. Rare but increasing instances of using such measurement instruments in social construction and other orientations can be found.

In strictly qualitative approaches, theorists are often left to describe and design their own results indicators. Usually, these are in the form of structured interview questions that can be analyzed for pattern responses. The constant comparative method is a common and high-utility way of developing results indicators for social construction theory building.

Once a theorist is familiar with results indicator options, he or she can select appropriate measurement strategies and move forward with the theory-building project. The increasing power of, and access to tools like Google Scholar (http://scholar.google.com) make searching out results indicator options more efficient, though the task of selecting the appropriate instrument requires content expertise.

Sub-Step 2—Develop instruments if appropriate instruments cannot be found. There are cases where measures of important concepts might not exist. In these cases, theorists are required to take a detour and develop measures of the desired concepts in order to proceed. The entire discipline of psychometrics is devoted to the development of measurement instruments for research in applied disciplines. Instrument development can be a complex, yet highly rewarding, activity, though it will surely delay the theory-building effort for some time. Most approaches to instrument development involve the use of a subject matter expert panel, followed by a large sample data collection specifically for assessment of score validity and reliability properties. Statistical expertise is required to make instrument development rigorous and the resulting product useful in applied disciplines (see Swanson & Holton, 2007).

By either selecting an appropriate existing measure or developing a new one, the theorist must arrive at a way of measuring changes in the concepts on which the theory is based. Results indicators often use the phrase “as measured by” to include the specific measurement instrument in the statement of relationships. For example:

• Employee engagement will increase as a result of including them in large-scale change management meetings as measured by the Gallup Q12 engagement questions.

• Team effectiveness will increase as a result of team-building activities as measured by team consensus ratings.

• Patient well-being will increase as a result of sending them flowers in recovery as measured by descriptions of hopefulness, outlook, and attitude.

Step 3—Develop Research Questions

The development of research questions is the final step in connecting the theory to the empirical world. Research questions are a natural bridge into research design and the next phase of theory building—the Confirm phase. Furthermore, research questions specify the activity under inquiry and may reveal some of its underlying assumptions. They also often identify an expected relationship among two or more variables.

Research questions also add a high level of specificity to theory building. Theories are broader and more encompassing than models. Models themselves can be highly complex and involve numerous relationships. Developing research questions forces the theorist to parse out specific, manageable portions of the theory. In other words, research questions are not likely to cover a whole theory—they are like pieces in a puzzle. There are usually too many relationships in a theory for a single research study or set of research questions to address. This is why theory building usually results in a program of research that may span a long period of time.

OUTPUTS OF THE OPERATIONALIZE PHASE

Outputs from the Operationalize phase are “confirmable propositions, hypotheses, empirical indicators, and/or knowledge claims” (Lynham, 2002a, p. 232). These outputs are clearly evident in the approaches to operationalization reviewed here and in the Operationalize phase of theory building as we have defined it. A theory without these elements does not constitute a theory because there would be no way to judge its accuracy in describing or explaining some instance of human activity.

SUMMARY OF THE STEPS

The Operationalize phase involves three steps: (1) describing propositions, (2) describing empirical indicators, and (3) developing hypotheses (Figure 5.3). These three activities connect the theory to the empirical world by specifying how it will be judged. Operationalization is traditionally thought of as a purely quantitative approach to defining expected outcomes and research hypotheses. However, we have seen an increase in the use of operationalization concepts such as hypotheses in a variety of philosophical orientations, making the idea of confirmation criteria more widespread and flexible.

FIGURE 5.3 Steps in the Operationalize Phase of Theory Building in Applied Disciplines

QUALITY INDICATORS FOR THE OPERATIONALIZE PHASE

There have been no published criteria for assessing operationalization efforts, and scholars have not made clear what successful or well-done operationalization looks like. Based on our own experiences with theory building, we believe some indicators are logical and useful for judging progress in this phase. These are described here with specific application to operationalization work.

Criteria for Assessing the Propositions, Results Indicators, and Research Questions

Three general criteria can be applied to the propositions, results indicators, and research questions generated in the Operationalize phase of theory building. They are parsimony, the quality and track record of measurement instruments, and the specificity of the research questions.

Parsimony. Parsimony is a useful criterion in all of the theory-building phases. It is specifically applied to each step of the Operationalize phase to make theory building manageable. Using parsimony to assess the Operationalize phase means that a minimum number of propositions, results indicators, and research questions result while still including all of the relationships specified in the Conceptualize phase. It is clear that as the number of propositions and empirical indicators increase, so do possible hypotheses (Dubin, 1978). Ultimately, the number of hypotheses depends on the energy of the researcher. For the sake of designing clear and concise research studies (in the next phase—confirmation/disconfirmation), hypotheses should be kept to a minimum.

Parsimony applies particularly when thinking about designing manageable research studies that are coherent and bounded. Of course, any theory of applied human activity is likely to be complex. These theories involve more hypotheses than a single research study can hold. Therefore, it is useful to consider a program of research that may take years to accomplish some level of overall verification.

Quality and Track Record of Measurement Instruments. Using measurement instruments in applied disciplines raises the issues of validity and reliability to the top of the list. Validity and reliability are extremely important because they provide a sense that the instrument scores are accurate and consistent. Though it is good practice to report validity and reliability of scores in research studies, a surprising number of researchers rely solely on previous reports of such information. Instruments with long histories of use and repeated demonstrations of valid and reliable scores in a variety of contexts inspire confidence and lend to the quality of operationalization. Newly developed instruments tend to raise a variety of questions as they simply do not have established track records. When choosing instruments to measure the expected characteristics, the history and background of the instrument is an important consideration.

CONCLUSION

This chapter has presented the Operationalize phase of the five-phase method for theory building in applied disciplines. Existing strategies for operationalizing theories were reviewed that illustrate the concept of operationalizing theories from a variety of perspectives. The general Operationalize phase was described, with its three major steps being (1) describe the propositions, (2) describe the results indicators, and (3) develop the research questions. Each of these steps was described with examples from a variety of theoretical perspectives, showing the utility of connecting to the ideas developed in the Conceptualize phase to assessment strategies in the real-world Confirm phase. The next chapter will describe the Confirm phase, which requires the theorist to gather evidence of a theory’s fit with the world in which it is expected to operate.