This means this. This means that. will guide you through the morass of meanings that our culture creates. Seventy-six sets of basic semiotic concepts will be explored through a variety of objects, images, and texts. Each set will be presented with a question. Readers can then consider their own answer before turning the page to find the author’s answer. In this way, the reader is challenged to think about how meanings are made, interpreted, and understood.

Semiotics is mentioned regularly in newspaper articles, in magazines, and on radio and television. But what is semiotics, and why is it important? Semiotics is defined as the theory of signs. The word “semiotics” comes from the Greek word semeiotikos, which means an interpreter of signs. Signing is vital to human existence because it underlies all forms of communication.

Signs are amazingly diverse. They include gestures, facial expressions, speech disorders, slogans, graffiti, road signs, commercials, medical symptoms, marketing, music, body language, drawings, paintings, photography, poetry, design, architecture, film, landscape gardening, Morse code, clothes, food, heraldry, rituals, and primitive symbols—and these are just some of the many things that fall within the subject of semiotics.

To see how signs work, consider the following:

Stop means Stop

Apple means Apple

Crown means Crown

Now compare this:

Stop means Danger

Apple means Healthy

Crown means King

Let us suppose that we see a word saying “Stop,” an image of an apple, and an object that happens to be a crown. In order to make sense of the signs “Stop,” “Apple,” and “Crown” we have to ask: what do these signs mean? In doing this, we have to be careful because signs can easily be misunderstood. The word “Stop” might tell us that there is danger ahead, or it may indicate a place from which you can take a mode of transportation, like a bus stop; the image of an apple may suggest that there is something healthy to eat, or it may be a symbol of youth or beauty; and our object, which is a crown, may indicate the presence of a monarch, or it may tell us that there is someone nearby who is about to attend a fancy dress party.

Signs are important because they can mean something other than themselves. Spots on your chest can mean that you are seriously ill. A blip on the radar can mean impending danger for an aircraft. An X on a map can mean that there is buried treasure. Reading messages like these seems simple enough, but a great deal depends on the context in which they are read. Spots on the chest need to be judged in a medical context; a blip on the radar needs to be read within the context of aviation; and an X on a map needs to be judged in the context of cartography. Signs are not isolated; they are dependent for their meaning on the structures that help to organize them, along with the contexts in which they are read and understood. Semiotics, then, is (among other things) about the tools, processes, structures, and contexts that human beings have for creating, interpreting, and understanding meaning in a variety of different ways.

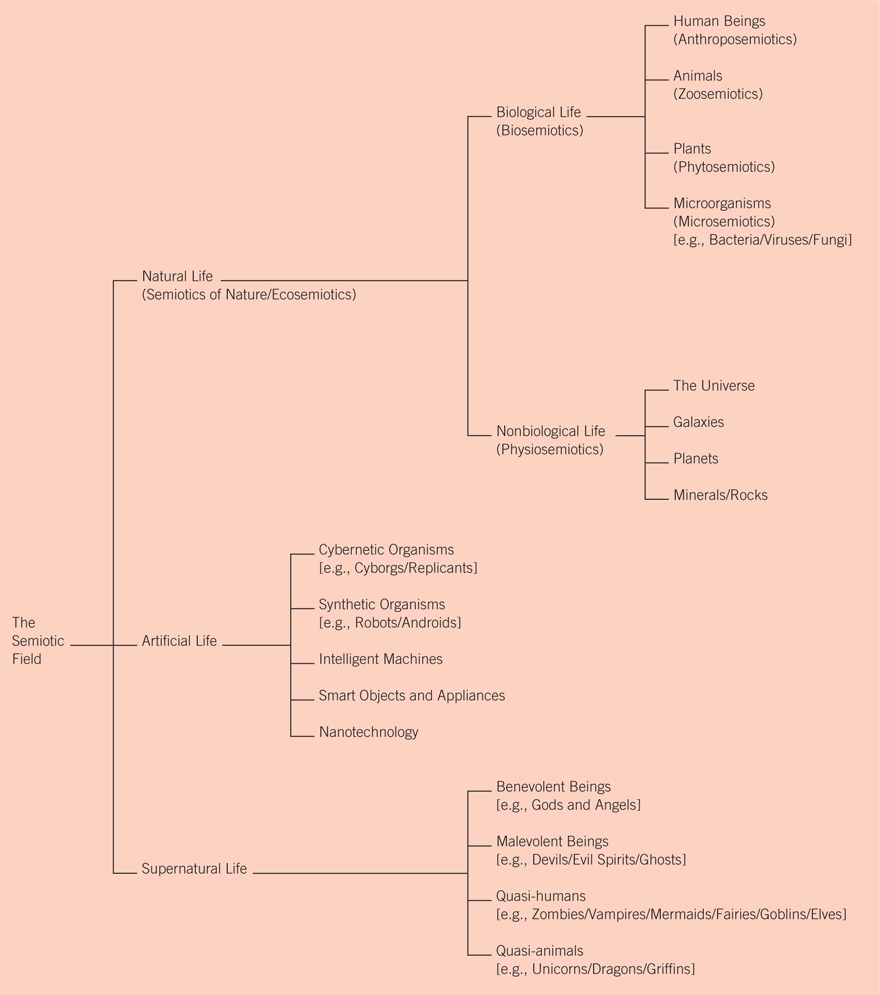

To get a sense of the enormous range of semiotic phenomena that relate to human life, I have constructed two diagrams (see pages 6 and 9). The first diagram helps to locate what is called “anthroposemiotics” (the study of meanings as they relate to human beings) within a wider field of semiotic interest; the second diagram concentrates on anthroposemiotics itself, which, for the most part, is what this book is about.

We can think of semiotics as applying, in the broadest sense, to life. The reason is simple. All the forms of life that we can identify have meaning for us. So, what exactly is life? In order to understand what life is we should first try to categorize it, before going on to say something about the important distinction between having a life, living a life, and leading a life.

Life can be categorized in various ways. I have chosen to treat it in the broadest sense possible by dividing it into three basic forms: natural life, artificial life, and supernatural life. As we shall see, natural life is discovered life; artificial life is invented life; and supernatural life is imagined life.

Natural life is apparent to us from our immediate environment. It is life as we ordinarily know it. It is such that we can make discoveries about it. Humans, animals, plants, and microorganisms, along with the universe, galaxies, planets, minerals, and rocks, fall into this category. In fact, anything that we can observe and study using the theories and methods of the natural sciences (biology, chemistry, and physics) or the human and social sciences (e.g., psychology, sociology, politics, art, design, linguistics, economics, geography, anthropology, philosophy, communication studies, media studies, and material culture) will count as a form of natural life in the sense that I am using it.

Natural life can be contrasted with artificial life. Artificial life is not discovered in nature. Instead, it is invented by human culture. This kind of life may be wholly or partially non-natural. Artificial life is simulated or synthesized, often with materials that are nonbiological. Due to this nonbiological element, there may be a debate about whether artificial life is truly “real.” Such things as replicants, cyborgs, robots, androids, and intelligent computers may appear to imitate human behavior, but we may still have doubts about the extent to which these forms of life can genuinely think, feel, and have consciousness in the same way that humans do.

Supernatural life is different again. Supernatural life is not life as we ordinarily know it. Instead, it is a form of life that transcends ordinary human knowledge and understanding. We come to know about supernatural life either because we imaginatively speculate upon it (as we do when we envision vampires, mermaids, or unicorns) or because we complement certain acts of faith by imagining the qualities that it might have (as we do if we believe in gods or angels). This form of life is strange to us because natural laws or processes cannot explain it. However, because gods, angels, zombies, and mermaids are often represented as having a humanlike form, and unicorns, dragons, and griffins are often very animallike in their appearance, they are apt to seem familiar. (The distinctions I have drawn are not hard and fast, and there is not always a strict division or consistency between what might be counted as a religious, mythical, or fictional form of life; nor is there any method or rule which can tell us which forms of supernatural life, if any, are real as opposed to imaginary.)

Having divided life into these three central forms, we can now discuss the kinds of lives that they might enjoy. To do this fruitfully, we need to make a distinction between things that:

1. Have a life

2. Live a life

3. Lead a life

Things that have a life come into existence, persist for a certain amount of time, and then cease to be. The lives of human beings, of animals and plants, of particles, galaxies, and planets, robots and intelligent computers, material objects, and even of angels, vampires, fairies, and unicorns all conform to this pattern of birth, life, and death.

Things that live a life form a more restricted class. They may engage in reproduction, grow, and develop, undertake autonomous activity, have a certain degree of complexity, engage in adaptive behavior, and be able to process chemicals so as to gain energy. Most humans and animals do these things. In this sense, we want to say that they are living their lives.

Finally, there are things that have a life, live a life, and also lead a life. Leading a life is about making plans and having projects; it is about decision-making and development, fitting means to ends, conducting oneself according to certain moral codes, being part of a system of values, and trying to make sense of the world in complex ways. These are the sorts of elements that make up typical human lives. They are the things that give human life a meaning. In other words, being human is having the potential to lead a life.

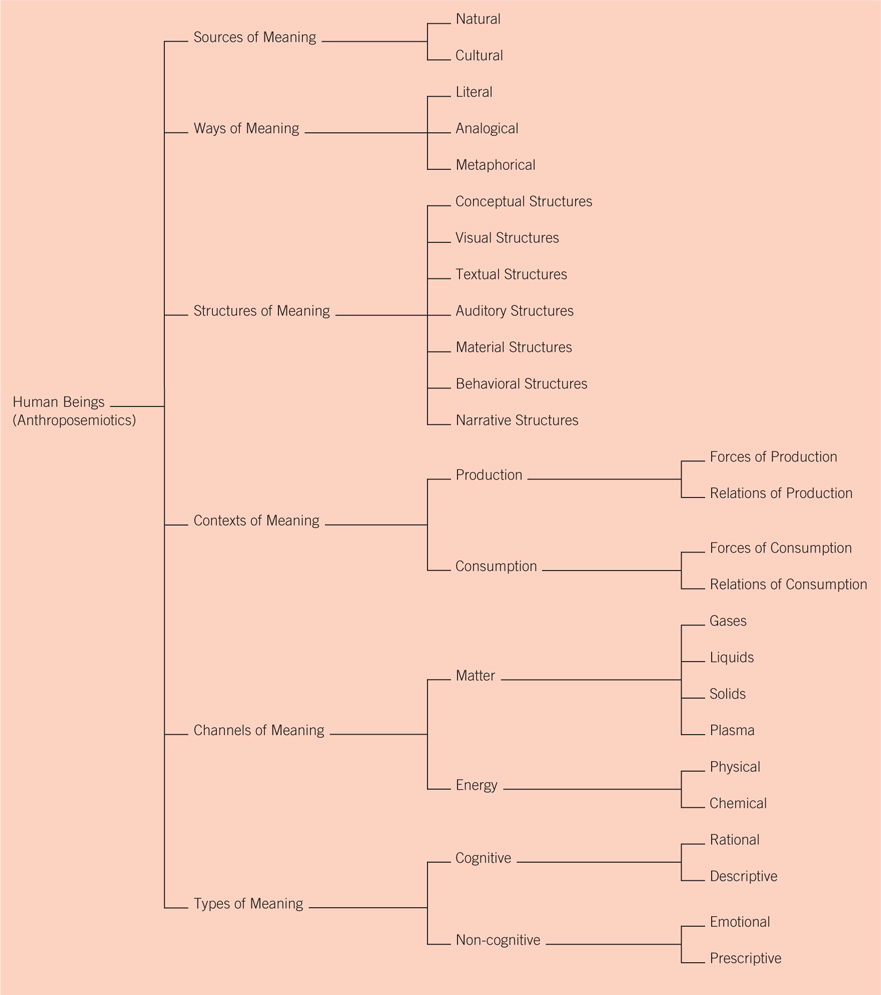

Having divided life into its different forms, and having said something about the difference between having, living, and leading a life, we can now move on to how things relate to the semiotics of human beings (i.e., anthroposemiotics). To get a sense of how anthroposemiotics might be understood, consider the diagram opposite:

SIGNS AND SIGNING

Signs are everywhere. But how exactly are they shaped, communicated, and understood?

In the case of human beings, signs are shaped by the sources and resources that are used to make them, formed by the cultural structures into which they are woven, communicated through a series of diverse channels, and understood in terms of the nature of the societies that created them.

There are many possible ways to help us understand how signs work. For purposes of simplicity, let’s use the headings that I have identified in our second diagram:

• Sources of Meaning

• Ways of Meaning

• Structures of Meaning

• Contexts of Meaning

• Channels of Meaning

• Types of Meaning

Sources of Meaning (Where the Message Comes From)

Signs come from two basic sources: the first is natural; the second is cultural. Natural signs arise from the way in which nature takes its course. Anything that is considered natural, or to have a natural aspect to it, can be considered under this heading. Our immediate environment of animals, vegetables, and minerals all exhibit features that have natural meanings to us as human beings, as do the further environments of the cosmos. (Here anthroposemiotics links with zoosemiotics and phytosemiotics.) Natural meanings are not invented by human beings; they are discovered by them. For example, the appearance of a rat on which there are infected fleas such as Xenopsylla cheopsis means that there is the possibility of catching the bubonic plague; evidence of the fungus Phytophthora infestans on potatoes means that they have potato blight; and discovering that a substance has the atomic number 79 means that we are in the presence of gold. In contrast, culturally produced signs depend not on how nature is, but on how we are.

Cultural signs are those that we have invented to communicate with each other in complex ways. For instance, an image of a rat might be a sign of fortune and prosperity (as it is in certain parts of China). A picture of a potato that has blight might be a sign of famine (as it was in the great Irish famine). A gold ring might be a sign of marriage (as it is in the eyes of certain Westerners). In each of these cases, we have to understand the convention that is being used in order to grasp the meaning that is being communicated. All of these signs, then, reflect aspects of the society in which they are pieces of communication.

This is not to say that a sign will always come from a source that is purely natural or purely cultural. Sometimes a sign involves elements that are both. Consider the way in which we categorize the colors of the rainbow. According to Isaac Newton, there are seven colors in the rainbow. The colors that he identified in 1671 were red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. Their corresponding approximate wavelengths are:

Red | 650nm (nanometre) |

Orange | 590nm |

Yellow | 570nm |

Green | 510nm |

Blue | 475nm |

Indigo | 445nm |

Violet | 400nm |

Newton’s categorization of the colors of the rainbow might seem to be something based simply on how nature is because the wavelengths of these colors seem verifiable by scientific means. However, the color spectrum is in fact continuous, with one color blending into the other; so it is up to us to decide where to draw the dividing lines between the colors that we experience. One way we might do this would be on the basis of those colors that we think can be readily distinguished with the naked eye.

At this point, we should note that it is a somewhat curious feature of the rainbow that indigo and violet are not always as easily discernible as we might think. To see this, look at the following image of a rainbow and then ask yourself how many colors you can actually see.

Fascinatingly, Newton’s manuscripts reveal that when he first conducted his experiments into rainbows he found only five colors. However, in the Optics of 1704 he added two colors, to make seven in all. So why did Newton change his mind? The reason seems to be that Newton was impressed by the mystical qualities of the number seven, which at the time was the number of the planets thought to exist, as well as the number that the ancients thought symbolized God’s perfection. By insisting that the rainbow had seven colors, then, Newton gave the rainbow the mystical quality that he thought it should have. Of course, there is now also a cultural expectation that leads us to say that there are seven colors in a rainbow. But we would do well to remember that this was an idea invented by Newton. Moreover, it is not an idea readily accepted by other cultures. (Notice that anthropologists have discovered that certain cultures, such as the Sioux from South Dakota, have words like toto that cover both the “blue” and “green” parts of the spectrum.). Thus, the number of colors that we identify in a rainbow may be influenced by the science of wavelengths (which is apt to make our decisions seem natural), as well as such things as the mystical powers of numerology (in the case of Newton), along with the color concepts that we happen to be using (so that if we expect a distinction between indigo and violet it is easier to find one).

Ways of Meaning (What Kind of Message it is)

Signs can be literal, analogical, or metaphorical. All of them provide us with ways to make meaning.

Sometimes there is a good reason for signs to be literal. This is the case with instruction booklets for electrical goods. It is no good if an instruction booklet for a piece of electrical equipment contains analogies or metaphors. If we are confused about how a certain piece of electrical equipment is supposed to work, this may lead to a breakdown in its operation or even put us in mortal danger.

Analogies make meaning. However, analogical ways of meaning are rather different from literal ways of meaning. Analogies, whether obvious or surprising, help us to map one set of meanings onto another. They allow us to draw out likenesses between such things as people, situations, objects, images, texts, thoughts, and ideas. Here are two obvious analogies. If I eat a slice of cake and it tastes good, I assume that it is very much like the other slices of the same cake. In view of this, I might recommend it to a friend. In this instance, I assume that part of the thing (the slice) is like the whole thing (the cake). In contrast, I might buy a new car that I think is not worth the money. In this case, I might warn others not to buy it. In this instance, I am drawing an analogy between an individual car (a token thing) and cars of the same model (a type of thing).

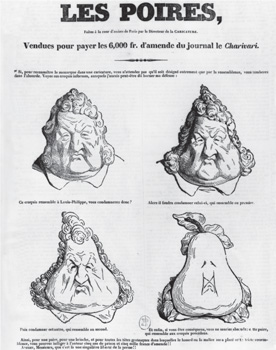

Analogies like the ones just described are so obvious to us that we hardly notice we are using them. However, some analogies are more surprising—the connections may be less obvious. In such instances, an analogy may only work in a very specific respect. For instance, a drawing of a person may be a caricature. In this case, certain facial features may be distorted and exaggerated, but the overall likeness may still be maintained. Here is an example of a face likened to a pear:

Metaphors are different from the other ways of meaning because they draw out connections between ideas, concepts, objects, images, texts, events, and processes that seem quite tenuous on the surface. Metaphors operate not by saying that one thing is like another (as is the case with analogies), but by insisting that one thing is another. The metaphors that we use tend to reflect certain features of the society in which they are produced. In the Western world, we live in a society that is largely mechanistic and consumerist in its outlook. So when it comes to discussing all manner of topics we often use mechanistic and consumerist metaphors that reflect this outlook.

Let’s take one concrete and one abstract example of a metaphor to see how they operate. When discussing a concrete topic such as disease, we often talk in mechanistic terms. This leads us to speak about the war against AIDS or the fight against cancer. The idea is that there really is a battle being fought against the diseases that we wish to conquer. The same point about the influence of society applies when we speak about more abstract topics such as time. Here, we frequently discuss matters in consumerist terms: we talk about using time, wasting time, saving time, and spending time, as if time were a commodity like money, rather than a process that unfolds.

Signs, then, whether they are literal, analogical, or metaphorical, reflect the outlook that a given society seems to share.

Structures of Meaning (How the Message is Framed)

Signs are given meaning by the way they make use of certain structures. The structure employed is sometimes immediately detectable, in which case we can say that it is part of the surface structure of the piece of communication; if it is not immediately detectable, we can say that it is part of the deep structure of the piece of communication.

We can use storytelling to illustrate the difference between surface structure and deep structure. It appears that all human beings, whether ancient or modern, feel the need to tell stories. That is why in many different kinds of society we find similar folklores, fairy tales, legends, proverbs, sayings, and riddles, whether they end up in the form of anecdotes, gossip, novels, plays, Urban Legends, operas, soap operas, comic strips, “reality” television programs, or news stories. Due to the ubiquity of stories in every culture around the globe, we might expect them to share certain structural features along with certain common meanings. One way to understand their similarities is to look at these features.

The elements of stories that are obvious to any reader are those that form the surface structure. These are the characteristics of the narrative that are made evident to us as the story unfolds. They include: character (the developing role of the hero, heroine, villain); themes (the power of love, the horror of war, the conquest of fear, the acceptance of death); plot (overcoming the monster, rags to riches, the quest, voyage, and return, comedy, tragedy, and rebirth); genre (romance, saga, mystery, adventure, thriller, war, science fiction, and horror); style (formal or informal); dialogue (vehicular or vernacular); motifs (the use of symbols such as swords, magic wands, and aspects of clothing); setting (the wilderness, the village, the city); the position from which the story is told (from the first-person, second-person, third-person perspective, or multiple narrators); and the tense of the piece (past, present, or future). These features are readily identifiable and can often be understood in quite a literal way by the audience.

In contrast, the elements of stories that may not be immediately apparent to the reader are those that form the deep structure. The deep structure is important because by accessing it we can reveal the underlying meaning and importance of what is being told to us. For instance, the deep structure might be there to persuade the reader of the value of (or, in some cases, to question the value of) such things as traditional values, dominant political ideologies, prevailing ethical systems, preferred social attitudes, established cultural norms, current forms of knowledge, and existing institutional practices. For example, it might be argued that, while Jane Austen wishes to defend certain traditional ideas about romantic love in Pride and Prejudice, Gustave Flaubert seeks to challenge them in Madame Bovary.

To see how structure works, let’s look briefly at another story: Sleeping Beauty.

In terms of its surface structure, Sleeping Beauty might be thought of as a love story. The hero (the prince) falls in love with the heroine (the princess) and then tackles various obstacles (including the temptations of the wicked fairy) in order to consummate their relationship in marriage. Interpreted in this way, we might think that the story exemplifies the theme of the power of love to overcome seemingly insurmountable barriers.

The story’s deeper structure, however, might reveal a series of meanings that are rather different. It might be argued that the story is there to reinforce prevailing systems of ethics (e.g., those advocating sexual fidelity) and certain dominant political ideologies (e.g., those reinforcing stereotypes concerning class and gender).

The underlying structure of the story may be revealed in various ways. One way is through a discursive examination of the text. Such an examination involves looking at aspects such as the formal qualities of the language that is used to tell the story. By paying close attention to the choice of words that the author uses, we may start to see not only things about the author’s own—perhaps partially hidden—views, but also the views of the characters that inhabit the story itself.

In the case of Sleeping Beauty, for example, we might look at the frequency with which certain words occur in a particular version of the story. In this instance, the text might reveal that the princess is repeatedly described in terms of her beauty, grace, health, goodness, and kindness, that the prince is portrayed as handsome, and that the wicked fairy is viewed as selfish and greedy. In telling a story like this, the author may be trying to reinforce certain traditional ethical values and gender stereotypes simply by repeating certain words in the hope that they resonate in the reader’s subconscious.

Another way to find the deeper level of Sleeping Beauty is by drawing comparisons with the overall patterns of other fairy tales. By examining fairy tales in general, we may discover that they have the same underlying narrative features. Two of them might be: 1) that the hero or heroine is presented with a seemingly impossible task, and 2) that the villain is punished in the end. Once these general features are discovered, we may see the story of Sleeping Beauty as revealing a more general unconscious fear (reflected in other such tales) that evil could triumph over good.

Contexts of Meaning (Where the Message is Situated)

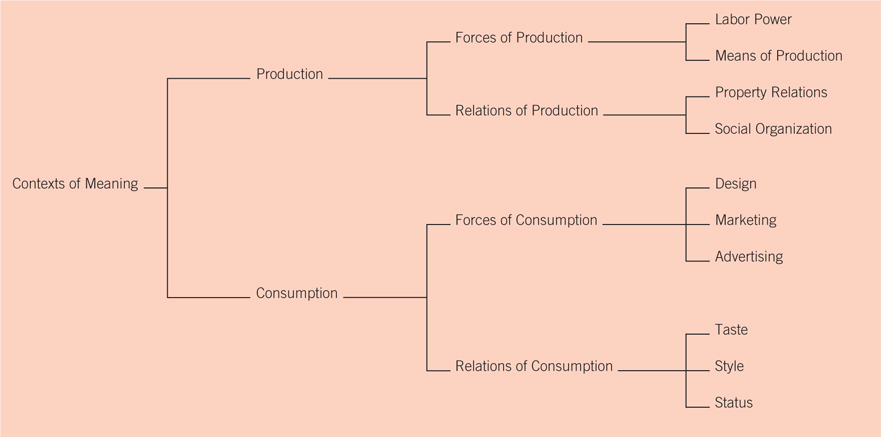

Signs take their meaning from the contexts in which they are produced and consumed. I have extended part of the Anthroposemiotics table (see page 9) into a separate diagram (see below) in order to show this:

This diagram serves to illustrate the way that the shift of emphasis from production to consumption has changed the nature of the distinctions we often make between others and ourselves. We were once confined by the strictures of class and tradition to conform to certain expectations concerning the social hierarchy, but these strictures have started to fracture under new regimes of consumption, particularly in the Western world. This has led us to replace some of the old divisions of class and tradition with new distinctions based on such things as taste, style, and (more free-floating forms of) status. This has happened because the instruments that make up the forces of consumption (such as design, marketing, and advertising) have created certain relations of consumption (they have enabled new divisions between people concerning taste, style, and status to arise). Notions of taste (see Bourdieu), for example, have enabled us to maintain social distinctions in relation to gender, race, and class by encouraging systems of classification based on aesthetic judgment and education. Ideas about style (see Hebdige) have helped to sustain specific cultural and subcultural groupings by giving distinctive material form to certain kinds of lifestyle choices (e.g., through choices about clothing). Personal decisions concerning work, wealth, leisure, behavior, and language (see Packard) have aided people in upholding multileveled forms of ranking, all of which give us what we call “status.”

The table below sets out, in a simplified fashion, some features of contemporary society and culture that give a context to the signs that we create:

When considering this table, it is important to realize that although there has been a shift away from an emphasis on production toward a stress on consumption in the contemporary world, productivist ways of thinking and behaving have not ceased; in the West in particular, they have often continued to work alongside developing systems of consumption. For this reason, the meanings that we read into signs need to be sensitive to the various ways in which preexisting systems of production, and new systems of consumption, are operating (particularly in different parts of the world where the productive ethos is still dominant).

| The Production Ethos | The Consumption Ethos | |

| Societal Frameworks | Traditionalism | Cosmopolitanism |

| Economic Philosophies | Functional Rigidity/Insourcing | Market Flexibility/Outsourcing |

| Dominant Class(es) | Lower Class/Upper Class | Middle Class |

| Prevailing Aspirations | Work | Leisure |

| Value Systems | “You are what you do” | “You are what you consume” |

| Working Environment | Industry-oriented | Service-oriented |

| Living Structures | Common Cultures | Adaptable Lifestyles |

| Collective Attitudes | Conformist Acceptance | Questioning Individualism |

| Sources of Authority | Parents/Church/State | Experts/Analysts/Connoisseurs |

| Sexual Customs | Marriage Contracts | Committed/Fluid Relationships |

| Social Communication | Local Contact | Mass Media |

| Knowledge Bases | Established Wisdom | Epistemic Uncertainty |

| Learning Arrangements | Scholarly Elites | Educated Masses |

| Gender Archetypes | Wife/Mother Husband/Worker | Parent/Employee Plasticity |

| Cultural Identity | Self Certainties | Personal Crises |

| Political Commitments | National Loyalties | Transnational Allegiances |

The car provides a good example. Considered as a sign, the car has altered its meaning as societies have moved from production toward consumption. Let’s look at the productionist view of the car first. With the emphasis on (mass) production, the car was viewed primarily in terms of its function and singularity. This was the case with the traditional Ford Model T. Ford produced a basic car that was affordable, but the production line process meant there was no choice of style. As Henry Ford was supposed to have said about his car: “You can have any color, as long as it’s black.” Because Ford cars were all of the same type, there was no question of the purchaser making a comment concerning the style, taste, or status of what was being chosen.

This changed with the contemporary emphasis on consumption. Choosing to buy a Ford in a consumerist society is more than just a practical decision. This is because when choosing a Ford nowadays—rather than, say, a Chevrolet, Honda, BMW, or Rolls Royce—the consumer is forced to make certain decisions about style, taste, and status. The choice of your Ford is highly refined given that it is possible to opt for a Ford Granada, Ford Ka, Ford Fiesta, Ford Focus, Ford Mondeo, or a Ford Galaxy. In other words, the consumer has to decide not just to be a Ford “person,” but also whether to be a Granada, Ka, Fiesta, Focus, Mondeo, or a Galaxy “person.” In short, the emphasis on consumption has given rise to new cultural distinctions and alternative ways of constructing the social ladder.

Channels of Meaning (How the Message is Communicated)

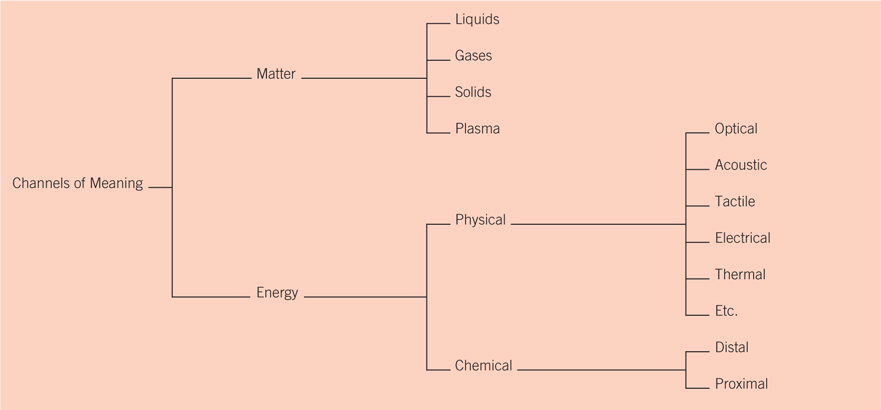

The signs we make are not independent of the channels of communication that we use to send and receive them. Channels of communication are important because they are the delivery systems for signs. Once again, by enlarging part of our second diagram we are able to show the range of channels through which communication can occur.

The diagram below shows that the channels through which we can communicate are very diverse. What is curious is that a change in the channel that is being used will often change how we react to the message that is being sent. For example, a conversation in person (using sound waves) will often feel very different to one that is conducted down a telephone line (using radio waves). Moreover, a person speaking to us on the phone may feel “closer” than a person speaking to us from a television, who might feel more “distant.” What is important to realize about this latter case is that the voice from the television may feel more “distant” than the voice coming through the telephone not because it has a different quality in terms of how it sounds (it may sound the same), but because there is no interaction.

We can observe similar shifts in meaning to those just identified when we compare the medium through which a given message is channeled. This is apparent when we consider how our view of the same tune (e.g., “Air on a G String” by J.S. Bach) may alter according to how it is being communicated. For instance, we could compare:

1. The tune played on a piano.

2. The humming of the tune.

3. A recording of the tune.

4. The tune in one’s head.

5. The tune as written down in musical notation.

In each of these cases, we might say that the tune is the same but the way in which it is communicated is very different.

Types of Meaning (How the Message is Understood)

Signs can be divided into two basic types: those that appeal to our rational side (i.e., the cognitive) and those that appeal to our emotional side (i.e., the noncognitive).

Forms of communication that are abstract are often connected more with our rational sense. Our rational sense makes calculations. Sometimes it is hard to care about calculations, as they don’t always engage us. The Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin knew this only too well. His view was this: one death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic.

Forms of communication that are concrete are often connected more with our emotional sense; this makes us feel things, often quite deeply. Some politicians, for example, have realized that if you want votes you have to make voters feel things. You can’t just appeal to statistics, because people find it hard to engage with them.

In providing information about people who have died, for instance, we might employ an abstract rational method or a concrete emotional method.

A statistic is abstract: the graph below shows a 75 percent increase in the murder rate in London in 2009. According to the graph, 375 people were killed.

A story is concrete: the cute little girl in the image below, whose name is Emily, died. She was one of numerous children murdered by their parents in London last year. Her father starved her to death.

We don’t have time to discover the stories of each of the people murdered in London represented in the graph on the previous page. Even if we did, we might not care to hear all of them. It just seems to be true that while a large group of people dying is terrible, it is not something that we relate to very easily. It is better then, if we want to make a point about death, to make it visual, specific, personal, and tangible. That way, we may connect with it without any problem.

In this instance, I have chosen a picture of a child that may engage your emotions. Children are innocent. They don’t deserve to die. Children are also cute. This image is being used, then, to help bring out latent feelings of affection. And, in this case, I have given the little girl a name. But it is not her surname; it is her first name. This makes the story more specific, personal, and tangible. I also told you a story about her. It was short and to the point. It was also tragic because it seemed as though she died for no reason.

In fact, there is a happy ending to this story: this little girl did not die. I invented the story. So there is no story to tell. And, just to let you know, she is not called Emily. (I invented the statistics about deaths in London, too.)

CONCLUSION

Humans understand the meanings of the signs that they create through the diverse ways in which they lead their lives. Getting this right is about understanding some of the things that we have just discussed: sources of meaning, ways of meaning, structures of meaning, contexts of meaning, channels of meaning, and types of meaning. But as we have seen, semiotics is not about simply accepting the meanings that we think are being given to us. Instead, it is about questioning, reframing, and sometimes making shifts in, the perspectives from which certain signs are viewed. Here are some simple examples to consider before we move on to the specific semiotic concepts that are discussed in the next eight chapters.

Take Toy Story. Toy Story is an animated film about two central characters: Buzz Lightyear and Woody.

Take Arsenal. Arsenal is an English soccer club.

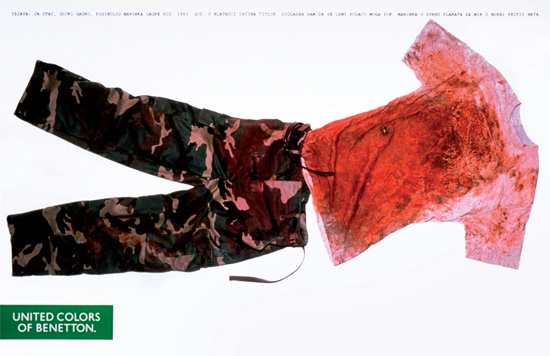

Take a Benetton billboard (see the example above). A Benetton billboard is an ad.

Film and soccer and advertising are the contexts we normally use for the purposes of interpreting and understanding the meanings of these things. But are these the right contexts? Perhaps Toy Story exists only to sell plastic replicas of the two leading characters to children. Perhaps Arsenal exists only to market merchandise to its fans. And perhaps Benetton exists only to campaign for social and political justice.

If any of that is right, then the contexts (respectively) of film or soccer or advertising might be subject to a shift. And if they are shifted, we should alter our readings of them accordingly.

The meanings of signs may be stranger than we think. That is the message of this book.