Introduction to Tourism Security

Abstract

This chapter provides an introduction to tourism security and how it relates to the general world of tourism. The chapter provides us with a historic overview of how tourism viewed security both before and after September 11, 2001. It also focuses on issues of safety, security, and surety. The chapter begins with an examination of the role of perceptions in tourism security, and then it provides a sociological analysis of how tourism security interacts with travelers. This chapter provides an overview of the types of tourism security and why the field is much more complex than what most laypeople assume.

The Tourism Phenomenon

Modern tourism is the world’s largest peacetime industry, yet it often remains an enigma, not only to tourism scholars and professionals but also to those who are tasked with protecting visitors and the tourism industry. Tourism is something that everyone recognizes, but almost no one can define. There are almost as many explanations as to what tourism is as there are tourists.

While there may be scholarly debates over tourism’s precise definition, there are still many areas of agreement. For example, most scholars will attest to the fact that tourism is about unique perceived experiences.

• Emotions are not necessarily connected to educational levels.

• Often, the higher the level of scientific reasoning within a society, then the more prone that society’s members are to periods of irrational thought.

• In tourism, fantasy and reality may merge into a world of simulata. Simulata is the reproduction of reality in such a way that it mimics reality without being reality. A good example of simulata is the movie Argo, which is a movie about a movie.

• Security and safety have as much to do with our perceptions of them as they have to do with concrete data.

If we look at the United States, then we can note both facts and interpretations of facts. According to the World Tourism Organization (WTO), the United States ranked second in tourism arrivals with 62.3 million; France ranked first with 79.5 million arrivals (International Tourism & Number of Arrivals, 2013). However, if a person from, to use the Russian term, “the near abroad” chooses to use a French airport, is that person a tourist? Should a person who arrives at one Paris airport, and a few hours later leaves from another Paris airport, be considered a tourist? Do we define that person as a transient or a visitor?

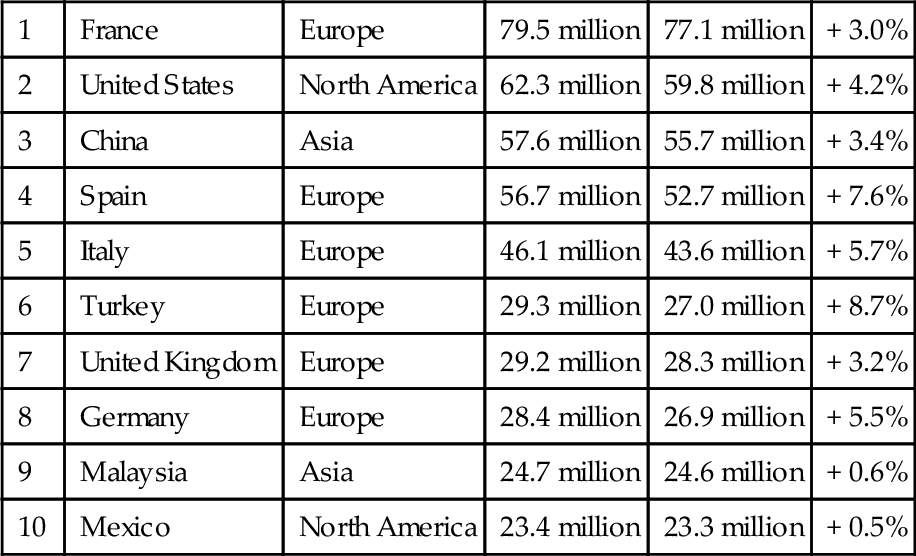

Despite these statistical challenges, tourism is big business. In every U.S. state, tourism is either the largest or the second- or third-largest industry. If we assume that an export item is defined as “bringing money from place X to place Y,” then tourism is also a major export item. Internationally, the tourism industry brings in millions of dollars, and it is one of the major job providers in many nations (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1

International Tourist Arrivals

| 1 | France | Europe | 79.5 million | 77.1 million | + 3.0% |

| 2 | United States | North America | 62.3 million | 59.8 million | + 4.2% |

| 3 | China | Asia | 57.6 million | 55.7 million | + 3.4% |

| 4 | Spain | Europe | 56.7 million | 52.7 million | + 7.6% |

| 5 | Italy | Europe | 46.1 million | 43.6 million | + 5.7% |

| 6 | Turkey | Europe | 29.3 million | 27.0 million | + 8.7% |

| 7 | United Kingdom | Europe | 29.2 million | 28.3 million | + 3.2% |

| 8 | Germany | Europe | 28.4 million | 26.9 million | + 5.5% |

| 9 | Malaysia | Asia | 24.7 million | 24.6 million | + 0.6% |

| 10 | Mexico | North America | 23.4 million | 23.3 million | + 0.5% |

Source: 2013 tourism highlights (2013).

Data taken from the World Tourism Organization for 2011.

www.indexmundi.com/facts/indicators/ST.INT.ARVL/Ranking (November 2, 2013).

Note: Different nations and organizations use different statistical methods and definitions of a tourist or tourist year, thus there will be slight variations in the numbers.

Tourism Terminology and History

The most common term employed among the industry’s professionals is “travel and tourism.” They use this term as if it were one word. Travel and tourism, however, are different from one another. Travel is one of the world’s oldest phenomena. In a sense we can trace it back to the beginnings of recorded history. Humans, just as other species, have consistently wandered from place to place. Ancient men and women traveled to find food or escape danger, and they traveled due to harsh weather conditions or natural phenomena. Yet, few people saw travel as a pleasurable experience; in fact, travel was hard work. The entymology of the word travel reflects this difficulty. We derive the modern word travel from the French word travail, meaning “work,” while the French derive travail from the Latin word trepalium, meaning an “instrument of torture.”

For most of human history, travel was hard work and often torturous. Until the modern era (and even into the modern era), travelers never knew when weather conditions might turn “roads” into seas of mud. Robbers and kidnappers often ruled the nights, and pirates, stealing both goods and persons, were common fare. To add to travelers’ woes, places of lodging were often cold and uncomfortable, they rarely provided privacy, and their food was irregular in both quantity and quality.

Modern Tourism Definitions

“Modern tourism” is one of those terms that most people understand, yet few people define well. There seems to be no definitive definition for “tourism.” Tourism is defined as: “the practice of traveling for recreation; the guidance or management of tourists; the promotion and encouragement of touring; the accommodation of tourists” (Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 1993, p. 1248). Other scholars and tourism scientists present alternative definitions. For example, in the preface to The Tourism System (1985), David Pattison, then head of the Scottish Tourism Board, writes: “From an image viewpoint, tourism is presently thought of in ambiguous terms. No definitions of tourism are universally accepted. There is a link between tourism, travel, recreation, and leisure, yet the link is fuzzy…” (p. xvi).

However, Goeldner and McIntosh (1990) define tourism as: “the science, art, and business of attracting and transporting visitors, accommodating them, and graciously catering to their needs and wants” (p. vii). Later on, however, they state: “Any attempt to define tourism and to describe fully its scope must consider the various groups that participate in and are affected by this industry” (p. 3). The authors then describe four different scopes of tourism: (1) persons traveling for pleasure, (2) persons traveling for meetings or to represent another, (3) persons traveling for business, and (4) cruise passengers on shore (p. 6). In fact, we can reduce McIntosh and Goeldner’s four categories into two, those traveling for pleasure or due to their own volition, and those traveling for commercial or business reasons.

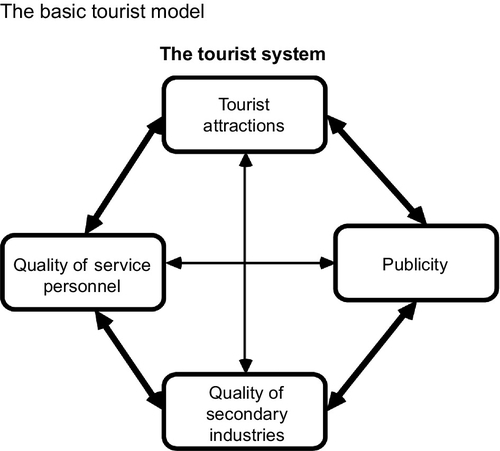

On the other hand, Choy, Gee, and Makens (1989) in the work The Travel Industry define tourism by stating: “the travel industry will be defined as “the composite of organizations, both public and private, that are involved in the development, production, and marketing of products and services to serve the needs of travelers” (pp. 4–5) (Figure 1.1).

Lack of a Unified Vocabulary

A review of the literature demonstrates that there is no one definition for the term “tourism,” or any one single word to describe the industry. In the United States, travel or “travel and tourism” is the preferred colloquial, while in many other countries, the term “tourism” tends to dominate. Moreover, there is no set definition for the term “tourist” or how this phrase differs from others, such as visitor, or even day-tripper. For example, is a person who leaves his or her town to shop in a town nearby a tourist or a visitor? What if the same person stays in a taxable place of lodging? Are day-trippers tourists, visitors, or neither? What about cruise passengers who spend just a few hours in a port of call? What are they to be called?

For purposes of this book, a tourist is defined as someone who travels more than 100 miles (160 km) and stays at least one night in a taxable place of lodging or with family and friends. A visitor is defined as a person who earns his or her money in place X but spends it in place Y. A traveler can be a tourist, a visitor, or simply a person passing through a locale on his or her way to another locale.

Tourism as a Social Phenomenon

Tourism is both a business and also a social phenomenon. In 2011, the economic volume of tourism equaled or, in some cases, surpassed that of oil exports, food products, or automobiles. So, tourism is a major player in international commerce. Not only is it a way to earn a relatively ecologically friendly income, but it also serves as a way for people from different parts of the world to gain a greater understanding of each other. The following figures, taken from the WTO, illustrate the importance of tourism.

Current Developments and Forecasts

• International tourist arrivals grew by nearly 4% in 2011 to 983 million;

• International tourism generated in 2011 was U.S. $1032 billion (€ 741 billion) in export earnings;

• UNWTO forecasts a growth in international tourist arrivals of between 3% and 4% in 2012.

(World Tourism Organization, 2012, Facts and Figures)

Defining Tourism Security

Considering how imprecise the terms “tourism” and “travel and tourism” are, it should not be surprising that in a composite industry such as tourism, the expression “tourism security” also suffers from the absence of a precise definition. This lack of precision with the terminology does not imply that tourism security practitioners are unaware of their major responsibility, which is to ensure both safety and security. What it does mean is that there are often questions as to who does what, as well as determining the boundaries of different roles. Just as in the case of law enforcement, police officers know that their job is fluid; they must always be prepared for the unexpected. Many police officers will state that their main responsibilities are to serve and protect anyone in their zone of duty, no matter where the person is originally from or how long he or she will stay in the area.

Classical and Modern Travel Challenges

While the nature of travel has changed over the course of time, the challenges facing modern travel are not new. At first, travel was just aimless wandering. By the Biblical period, two new aspects of travel had been added to the equation. Travel became necessary for international commerce, and pilgrimages began to emerge, providing not only a sense of the spiritual, but also a needed break from the drudgery of everyday life.

Ancient Middle Eastern texts, such as the Bible, tell of caravan traffic along the Futile Crescent (Babylonia to Egypt). Fairs were now common. At these fairs, people traveled to exchange goods, while the atmosphere of the fair added a sense of pleasure to the “travel” experience. From the first ancient fairs, the medieval fair was born. These early European fairs were not only places of commerce, but they also provided forms of entertainment, information exchanges, and relaxation. From the medieval period to the mid-twentieth century, travel underwent a transformation. Today, people travel for practical necessities, as well as to seek potential enjoyment. It is from this merging of necessity and enjoyment that modern tourism was born. Although tourism has numerous definitions, for the purposes of this book, we may see tourism as travel plus purpose, be that leisure or business.

Just as in the present day, many thieves in the past assumed that travelers would not be able to return to the sight of a robbery to pursue legal or punitive options, and that most travelers suffered from the disadvantage of unfamiliarity of place. Although, we can subdivide today’s travelers into two categories—those who travel for pleasure (the leisure traveler) and those who travel for business—many of yesteryear’s problems still exist today. Below is a partial listing of some of the reasons that travelers may become victims.

• Travelers often assume where they are going is safe.

• Travelers often lack proper details about their destination and the places through which they will pass on their way to their final destination.

• Travelers often have multiple destinations. This means that they may not even notice that they have lost something of value and when noticed may not have any idea as to where the object was lost.

• Travelers often forget objects of value or lose them along the way. Thus, the traveler may have no idea as to whether the object was lost or stolen.

• To travel is to take risks; travelers often take risks that they would not take at home.

• Travelers are often tired and/or hungry. Therefore, they may be thinking of immediate biological satisfaction rather than safety and security needs.

• Travelers do not know the place to which they are traveling (or through which they are passing), as well as the local population. Travelers may not know the local customs, tipping schedules, language, geography, and points of danger. Consequently, it is the traveler who is always at a disadvantage in a confrontation.

• Travelers often let down their guard or lower their level of inhibition.

• Travelers are on a schedule, so they often lower their standards of security and safety for the sake of staying within a specific time frame.

• Rarely are travelers willing to invest the time needed to file a police report, and they are often unwilling to spend the time and money needed to return to the site in order to testify against their assailant.

• Travelers are prone to become upset easily, leading to acts of rage.

• Few travelers are professional travelers, but most con artists and thieves are highly adept at what they do. In the competition between the traveler and the victimizer, the victimizer all too often has the advantage.

Concepts of Leisure and Leisure Travel

The idea of leisure travel is also far older than most people imagine. Under a sociological view, leisure was more than merely free time. As far back as Biblical times it was considered an activity that served to define human beings. The Biblical texts speak not just of free time but also of leisure. In the first chapters of Genesis, we read: “And the heaven and the earth were finished, and on the seventh day (Saturday), God finished His work, which He had made, and He rested on the seventh day from all His work which He had made. And God blessed the seventh day and hallowed it” (Genesis 2:1–2, English Standard Version). The Biblical writers saw leisure as more than simply work stoppage; instead, they viewed the concept of leisure as a positive precept that was ensconced in the Ten Commandments. Much of the social legislation of Western society was inspired by the idea that human beings were more than mere machines to be used and then discarded. Without the principle of time being a precious resource to be used and enjoyed, then tourism could not exist. The sentiment that humans need more than merely the basics reaches its philosophical pinnacle in Deuteronomy, where the text states: “Human beings do not live by bread alone” (Deuteronomy 8:3, English Standard Version). In other words, what defines humanity is its ability to balance our working world with pleasure. Hebrew social law even divides the concept of rest into destructive rest (sikhuk), restorative rest (shvitah), and productive rest (nofesh).

However, the Biblical idea of rest and relaxation did not exist without challenges. The rise of modern capitalism produced the notion that time is money, so to waste time was a “sin.” The Industrial Revolution brought about the invention of machines that could work without rest. Therefore, rest and leisure stood in the way of economic progress. With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, the Protestant Ethic and Marxian thought were new ideas that began to define leisure. Both of these theories, in their own way, tended to see leisure as a poor use of time, as well as counterproductive to a healthy society. Thus, the Protestant Ethic, under the backdrop of the Industrial Revolution, tended to glorify work, and it saw southern European and Catholic traditions, such as the siesta, as examples of decadence. In some ways, these new social thinkers were correct. For example, the Spanish concept of the “hidalgo” meant that work was a social phenomenon about which one should be ashamed. The basic concept of the hidalgo was to exhibit great pride in having servants and in “doing nothing.”

This same sense of leisure nothingness, which in classical Hebrew is called “sikhuk,” also dominated much of classical Russian literature, such as Anna Karenina. Ironically, as history progressed, both Nazi and Marxist social thinkers came to despise the notion of leisure. The sign over Auschwitz, “Arbeit macht frei (Work makes you free),” is the most cynical transformation of leisure into a negative quality in history. Marxists, who hated the Nazis’ view of the world, oddly arrived at the same conclusions. Marxists and neo-Marxists viewed leisure as periods of nonproduction in which the upper-class bourgeoisie took advantage of the working-class proletariat.

Marxists then stood in direct opposition to the Hebrew biblical weltanschauung (worldview). The classical neo-Marxist theorists assumed that leisure and leisure activities represented a manifestation of economic disparity between the wealthier tourist and the poorer members of the economy. From their perspective, leisure activities were nothing more than another means of bourgeoisie domination over the proletariat. This notion of leisure belonging only to the upper classes would later manifest itself in the neo-Marxist notion that the tourist was in many ways responsible for his or her own victimization.

Tourism Security is More Than Criminal Behavior

To complicate matters further, tourism security deals with much more than just criminal behavior. Tourism professionals must continually fight against criminals who would seek to develop either a parasitic relationship with tourism or seek to take advantage of tourists and visitors. Visitors are often victims of acts that may not be illegal but are immoral and destroy a locale’s reputation. For example, shop owners may bother (harass) visitors, without technically breaking the law, to the point where the visitors no longer feel comfortable. Furthermore, local mores and customs mean that what is acceptable behavior in one culture may not be acceptable in another. Often, these cultural clashes are likely to occur in places where multiple cultures, and diverse economic statuses, are placed within the same geographic locale or forced to intermix with each other.

To add to the difficulties, there is a general confusion between issues of security, safety, and, in this book, what we call “tourism surety.” In a number of European languages, such as French, Portuguese, and Spanish, the same word is used for both security and safety. Security and safety experts do not always agree where one concept ends and another begins. For example, we speak of food safety, but if a person intentionally alters food so as to sicken someone else, then this act is no longer a food-safety issue but becomes a food-security issue. In the same manner, tourism specialists must worry about a traveler who deliberately carries a communicative disease from one locale to another for the purpose of harming others. Is such an act one of biological terrorism, a security matter, or an issue of safety?

Criminal Acts and Acts of Terrorism

As Brazil prepares for the 2014 FIFA World Cup Games and the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympic games, the country has been rife with criminal acts against foreign tourists. For example, BBC News ran the following headline “Brazil: Foreign tourist raped on Rio de Janeiro minibus.” The article went on to state that “the (foreign) couple's identities and nationalities have not been disclosed,” and that “Curbing violence is a major priority for the authorities in Rio, which is hosting the football World Cup next year and the 2016 Olympics” (2013, para. 3). Rio de Janeiro takes the problem of crime very seriously with what it calls a “shantytown pacification program” (comunidades pacíficadas), yet the city has still not been able to solve the rape issue, with over 488 rapes having occurred in December 2012.

Table 1.2 shows some of the difficulties in determining criminal acts and how they differ from terrorism in the world of tourism. Table 1.2 also emphasizes how terrorism is not the same as crime. Crime is an antisocial form of capitalism, and as such, its end goal is economic gain. Terrorism, on the other hand, is political in nature. Terrorists may use economic methods to fund their actions, but their ultimate goal is political in nature.

Table 1.2

Key Differences Between Acts of Tourism Crime and Terrorism

| Crime | Terrorism | |

| Goal | Usually economic or social gain | To gain publicity and sometimes sympathy for a cause |

| Usual type of victim | Person may be known to the perpetrator or selected because he or she may yield economic gain | Killing is a random act and appears to be more in line with a stochastic model Numbers may or may not be important |

| Defenses in use | Often reactive, reports taken | Some proactive devices such as radar detectors |

| Political ideology | Usually none | Robin Hood model |

| Publicity | Usually local and rarely makes the international news | Almost always is broadcast around the world |

| Most common forms in tourism industry are: | Crimes of distraction Robbery Sexual assault | Domestic terrorism International terrorism Bombings Potential for biochemical warfare |

| Statistical accuracy | Often very low, in many cases the travel and tourism industry does everything possible to hide the information | Almost impossible to hide Numbers are reported with great accuracy and repeated often |

| Length of negative effects on the local tourism industry | In most cases, it is short term | In most cases, it is long term unless replaced by new positive image |

Source: Tarlow (2001), pp. 134-135).

Tourism has become a front-line battleground, not only for criminals, but for terrorism as well. Tourism sites, known as “soft targets,” have often been successful objectives for terrorists. These acts of terrorism have taken place in both urban and rural settings, in countries considered “at peace” and in nations considered “at war.” As a result, terrorism has impacted the world of tourism in multiple settings and on a worldwide scale.

The following is a partial list of places where terrorism has been launched against the tourism industry.

• Germany

• Indonesia

• Israel

• Jordan

• Kenya

• Mexico

• Morocco

• Peru

• The Philippines

• Spain

• United Kingdom

• United States

The one unifying factor between these nations is that they all have a successful tourism industry. Tourism professionals, along with students of tourism, have wondered what attracts terrorist organizations to tourism. Below are some of the reasons for this attraction.

• Tourism is interconnected with transportation centers, so an attack on tourism impacts world transportation.

• Tourism is a big business and terrorism seeks to destroy economies.

• Tourism is interrelated with multiple industries; thus, an attack on the tourism industry may also wipe out a number of secondary industries.

• Tourism is highly media oriented and terrorists seek publicity.

• Tourism must deal with people who have no history. Consequently, there is often no database and it is easy for terrorists simply to blend into the crowd.

• Tourism must deal with a constant flow of new people, so terrorists are rarely suspected.

• Tourism is a nation’s “parlor” (i.e., it is the keeper of a nation's self-image, icons, and history). Tourism centers are the living museum of a nation’s cultural riches.

• Terrorists tend to seek targets that offer at least three of the four possibilities listed below, and these same possibilities often exist in the world of tourism.

1. Potential for mass casualties.

2. Potential for mass publicity and “good media images.”

3. Potential to do great economic damage.

4. Potential to destroy an icon.

Professional Fears of Addressing Crime and Terrorism

Traditionally, many tourism professionals have avoided addressing issues of tourism security and tourism safety altogether. There was a common (misplaced) feeling among them that even speaking about these subjects would frighten customers. Visitors would wonder if too much security indicated that they should be afraid. Especially in the years prior to 2001, the industry often took the position that the less said about tourism security and safety, the better. From the industry’s perspective, security professionals were neither to be heard nor seen. For this reason, many tourism locales, prior to 2001, employed what was called “soft uniforms.” The idea was to blend the security agent’s dress with that of the locale’s décor or theme. For instance, hotels in Hawaii had their security agents use aloha-type shirts that matched the island’s typical tourism dress code. Tourism professionals hoped that this blending of uniforms would permit low-profile security that would protect guests without their guests noticing that they were being protected.

In reality, nothing could have been further from the truth. For the most part, travelers and tourists, especially after September 11, 2001, tended to seek out places offering a sense of security and safety. Although a small minority of travelers seeks out dangerous endeavors, most visitors want to know what the industry is doing to protect them. They also wish to know how well prepared a local industry is if a security or safety issue should occur.

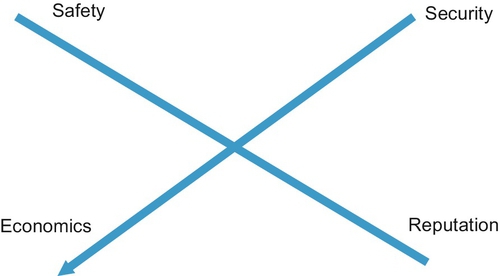

As noted above, although many academic disciplines make a clear distinction between security and safety, tourism scientists and professionals tend not to do so. Security is often seen as protection against a person or thing that seeks to do another harm. Safety is often defined as protecting people against unintended consequences of an involuntary nature. For example, a case of arson is a security issue, while a spontaneous fire is a safety issue. In the case of the travel and tourism industry, both a safety mishap and a security mishap can destroy not only a vacation, but the industry as well. It is for this reason that the two are combined into the term “tourism surety.” As shown in Figure 1.2, tourism surety is the point where safety, security, reputation, and economic viability meet.

Pre and Post September 11, 2001

In the Western world, modern tourism security has two distinct historical periods. The first historical period was prior to September 11, 2001. As has been noted, this period was marked by several historical trends within tourism:

• There was no clear distinction made between acts of terrorism and criminal acts. Terrorism was treated as if it were a criminal act rather than an act of war.

• Most tourism professionals underplayed the importance of tourism security. Agents were kept out of sight or given uniforms that blended in with the locale’s décor.

• Police and tourism officials often had no (or a minimal amount of) collaboration. Both sides of the public security/tourism line tended to know little about each other.

• There was often a pseudo-hostile environment between public safety agencies and tourism professionals.

• Public safety officials and tourism officials did not share a common vocabulary.

A few examples serve to illustrate these trends. If we look at the United States, the attitudes listed above prevailed despite the fact that many destinations and locales, such as Florida, had received a great deal of undeserved negative publicity in the 1990s, due to the unfortunate murders of, and assaults on, several foreign tourists. In many other nations around the world, the level of awareness was even lower. Tourism professionals even admitted that their industry required a safe and secure environment in which to thrive, but they often chose to look the other way. Furthermore, prior to 9/11, few U.S. police departments were aware of their responsibilities toward the tourism industry. Many police departments took pride in the fact that they treated tourists just like anyone else and had no special policies for tourists or police trained in tourism security. The idea that tourists or tourist facilities, such as hotels, were a high-risk group, that local police might need special training in working with a location’s out-of-town guests, or that the industry needed special protection were simply either unknown to most U.S. police departments or had not entered the realm of consciousness.

This first historical period came to a sudden closure on September 11, 2001, when the forced grounding of air traffic around the world meant that travel and tourism had come to an almost sudden and total halt. September 11, 2001, changed the course of travel and tourism forever, and it forced tourism professionals to realize that without tourism surety, no amount of marketing would save their industry. While many tourism professionals did not consider tourism security to be essential prior to 9/11, after that time, the industry radically changed its position.

Tourism Safety, Security, and Surety in the Post-9/11 World

Although many disciplines make a clear distinction between security and safety, tourism scientists and professionals tend not to. The reason is simple: a ruined vacation is a ruined vacation, and the fixing of blame is therefore a secondary activity. Another reason for this merging is that there are no clear and precise definitions of safety and security. Practitioners often view security as the act of protection of a person, place, thing, reputation, or economy against someone (or someone’s tool) that seeks to harm. They typically define safety as the protecting of people (or places, things, reputations, or economies) against unintended consequences of an involuntary nature. From the perspective of the travel and tourism industry, both a safety and a security mishap can destroy not only a vacation, but also the industry. It is for this reason that the two are combined into the term “tourism surety.”

Although we use terms such as “tourism safety,” “security,” or “surety,” in reality there is no such thing as total travel (tourism) security/safety. A good rule of thumb is to remember that everything made by human beings can also be harmed or destroyed by human beings. Also, there is never 100% total security. Accordingly, security, or tourism surety, is a game of risk management. The job of the tourism professional is to limit the risk to manageable levels. This is another reason why we use the term “surety,” which is a term borrowed from the insurance industry. Surety refers to a lowering of the probability that a negative event will occur. Surety focuses on improvement rather than perfection because it takes into account that risk is prevalent in everyday life. Since few people work according to strict academic guidelines, this book uses the terms “surety,” “security,” and “safety” interchangeably.

An Overview of Tourism Surety: The Pre-9/11 Years

In the first part of this chapter, we saw how travel and tourism professionals treated issues of tourism surety (security). Now, we return to the early years and see how police and other security agencies treated the topic. It is in these earlier years that the basic principles of tourism surety were first established.

In the 1990s, the idea that tourism security was important and required a partnership with other security professionals, such as hotel security departments, had only just started to enter into the collective psyche of the travel and tourism industry. Tourism textbooks treated the subject in a superficial manner, criminology texts ignored the topic completely, and there was little separate theory to support or guide police as to why they should even be concerned with another facet of their profession.

During the 1990s, even major U.S. tourism centers, such as Las Vegas and Honolulu, had done little to study the problem. Until 1990, there was no such thing as a tourism security conference. The first such conference was held in Las Vegas in the early 1990s. As stated before, the industry was still fearful of speaking openly about security, so this inaugural conference was called the “Las Vegas Tourism Safety Seminar.” The conference leaders chose the words seminar and safety (instead of security) so as to not scare people or call too much attention to the issue of tourism safety. As late as the 1990s, no police academy provided police officers with any special tourism training, and few police departments were even aware that the topic existed.

In 1992, several foreign tourists were murdered in Miami, and the media turned these deaths into a cause. Soon, Florida tourism officials were on the defensive. From the perspective of history, these incidents in Florida were incredibly important, not because a great number of people were injured, but because the negative publicity that Florida received made police departments sensitive to a whole new area of policing and the fact that new methods and units would need to be established. Perhaps for this reason, several police agencies in the early 1990s began to see the need for what was then called “tourism safety.” Among the pioneering departments were the Orange County (Orlando, Florida) Sheriff’s office, which developed a tourism task force lead by Detective Ray Wood; Clark County’s Metro (Las Vegas, Nevada), whose Sheriff Jerry Kelley asked his detective Curtis Williams to develop a task force; and Honolulu, Hawaii, whose Captain Karl Godsey worked with local tourism officials to develop what eventually came to be known as “the Aloha patrol.” By the end of the decade, other cities, such as Miami (Florida), New Orleans (Louisiana), New York City, Detroit (Michigan), and Anaheim (California), had also established some form of special tourism safety unit.

As the importance of tourism spread throughout the United States, the idea of tourism policing also spread. For example, Texas A&M University’s extension program asked me to develop a course for Texas communities in tourism safety, and it noted that tourism policing also aided police departments in related issues, such as:

• Ethnic diversity

• Cultural awareness

• Community policing

In the latter part of the decade, special police courses also began in less major tourism-oriented areas such as Long Beach (Washington), College Station (Texas), and Charleston (South Carolina). While these latter communities were not major tourism centers, tourism still played a significant part in their local economy. The field also continued to grow when the United States Bureau of Reclamation asked me to develop a groundbreaking tourism safety course for all of its facilities.

Starting in 1990, a series of tourism safety conferences began. The earliest ones were held in Las Vegas and Orlando. During the latter half of the decade, under the leadership of Don Ahl of the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority and I, the Las Vegas seminar has turned into a national seminar on tourism safety. It has also fostered a number of local spin-off seminars in such cities as Detroit, Honolulu, and Anaheim. Today, these seminars have become part of both the Spanish- and English-speaking worlds, with sessions in places such as the Dominican Republic, Panama, Colombia, and Aruba. Although each individual seminar often reflects specific local or national needs, there are a number of topics that unite these assemblies:

• The idea that tourism security is composed of multicomponents and is multifaceted

• The need for tourism security officials to explain to the industry that every security decision is, in the end, a business decision

• Tourism security is a highly complex profession that requires a tremendous amount of knowledge in many diverse areas, such as

• Intercultural communication skills

• Sensitivity training

• Gender roles

• Listening skills

• Anger management

Tourism security professionals are increasingly aware of the high level of professionalism exhibited by those who would seek to take advantage of tourists and the tourism industry itself. Although many visitors assume that tourism criminals (and/or terrorists who act against the tourism industry) are amateurs, the reality is that these criminals have become adept in sophisticated technology, and they study their victims (i.e., businesses, locales, or people) with high levels of precision.

Then, during the 1990s, there was a slow development of the general principles of tourism safety. In 1996, the International Association of Chiefs of Police (located in Arlington, Virginia) established its first course in tourism safety, and in 1998, George Washington University launched its first course in tourism safety via the Internet. In 1999, Orange County, Florida, attempted to establish a conference of major tourism cities. Some of the established doctrines included:

• Local police departments cannot assume that visitors will use the highest level of common sense when it comes to their own safety. Police departments and hotel/attraction security professionals will have to do what the visitor will not.

• Crimes committed against visitors cost the industry and local communities millions of dollars. Plus, these crimes can ruin a locale’s reputation for many years.

• Tourism protection requires partnerships. These partnerships include many aspects of the security and safety industries, government agencies, hotel managers, and tourism offices.

• The tourism industry needs the help of universities to understand and find solutions to the problems concerning visitor safety.

• Tourism security and safety must be handled on a regional, state, and national basis.

• Wherever there is tourism, there is a major need for tourism security and tourism-oriented policing/protection services training.

• Recognize that tourism is a significant item on the crime prevention and community safety agenda that has been slow to arrive in most countries.

The Post-9/11 Period

Soon after the attacks of September 11, 2001, it was not uncommon to hear people use the phrase “9/11 changed everything.” The numbers 9 and 11 have now become a new noun, 9/11, and to a greater extent reflect a new era of travel hassles and fear. September 11, 2001, may be considered the date when the travel and tourism industry lost its innocence. Along with much of the world’s economy, the travel and tourism industry suffered. To illustrate, in the city of Las Vegas, well over 10% of the tourism workforce (hotels, valets, etc.) lost their jobs within hours of the attack. Tourism professionals, who had avoided speaking about tourism security issues, now began to wonder if they might have been incorrect. Police officers were revered as heroes, while the public, which had been antimilitary due to the Vietnam War, now began to embrace the military. In the days immediately following 9/11, tourism officials throughout the world knew that they were in a fight for the very survival of their industry.

Moreover, the tourism industry faced another difficulty. The public now demanded what the tourism industry could not deliver: total security. Security professionals understood that no person or agency could ever guarantee 100% security. The trouble was that the public and the media refused to accept this fact. Instead of viewing successes, tourism had to deal with a media that chose to sensationalize every act or threat against tourism. This new form of “yellow-journalism by perception” created a new problem, the perception that travel was more dangerous than it really was. The travel and tourism industry now had to face three separate enemies: the terrorist who sought to destroy tourism, the criminal who sought to take advantage of the industry and its clients, and the media that inadvertently became an ally to the industry’s enemies.

More than a decade has passed since 9/11 became a household term. We often forget that in the years immediately following 9/11, the public begged for tighter airport security, “foreign” biological substances were found on airplanes, and fear manifested in the form of believing post office deliveries contained anthrax. At the dawn of the new millennium, newspapers reported, on an almost daily basis, threats by terrorist groups against transportation companies and prominent locations. Due to the shock of how vulnerable it was, the tourism industry began to see the world through different eyes, and tourism security evolved from hidden necessity to marketing tool. Tourism professionals realized they needed a great deal more than just cosmetic changes to beat the threats against their industry; they also needed cooperation from allies outside of the industry. Travel and tourism leaders turned to governmental agencies and to both public and private security for help. For example, in the United States immediately following 9/11, then President George W. Bush, along with several Hollywood stars, made a series of television adds encouraging the public to return to the world of travel. It was at this time (e.g., 2002) that the Department of Homeland Security was born. The Department’s official website notes:

Eleven days after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, Pennsylvania Governor Tom Ridge was appointed as the first Director of the Office of Homeland Security in the White House. The office oversaw and coordinated a comprehensive national strategy to safeguard the country against terrorism and respond to any future attacks.

With the passage of the Homeland Security Act by Congress in November 2002, the Department of Homeland Security formally came into being as a stand-alone, Cabinet-level department to further coordinate and unify national homeland security efforts, opening its doors on March 1, 2003. (Department of Homeland Security, 2002, Department Creation section).

The old paradigm of hiding security professionals was no longer valid. Eventually, visible security was not only in vogue, but it was understood to be a tourism-marketing tool. In a like manner, the tourism industry and local police departments realized that they could no longer afford to ignore each other and have a serious incident arise. It became clear to both travel and tourism officials and police departments that the best way to recover from terrorism was to prevent it. Industry and political leaders realized that it was only through vigilance, interagency cooperation, and a serious commitment to security that they would regain the public’s trust.1

After 9/11, tourism officials soon became intimately involved in national and international security issues. This involvement, however, was not a mere “love fest.” Tourism officials soon realized that governmental changes, such as the creation of the TSA in the United States, often were cosmetic rather than substantive. Furthermore, many of these changes added a new “hassle factor” that turned travel from a pleasure into a chore. Additionally, a number of high-profile mistakes were made by less well-trained “air security personnel,” which caused the public to rapidly lose confidence in government-run tourism security programs. It was also during the post-9/11 period that tourism security conferences went from small conclaves or seminars to large conferences. At the same time, universities, such as George Washington University in Washington, D.C., began to offer courses and/or lecture series in tourism security and safety.

TOPPs: The First Defense Against Tourism Crimes

Many communities have established special police units to aid in the tourism industry. The most common term in the English language to describe these units is “TOPPs,” which is an acronym standing for tourism-oriented policing/protection services. In Spanish the word is often translated as “seguridad turística” or “politur” (a composite word of the two Spanish words policía and turismo).

No matter what these officers are called, they share certain similarities. Although TOPPs units reflect local conditions, they tend to emphasize at least the following topics:

• Tourism's economic impact on the community

• Law enforcement's role in the special needs of specific demographic groups

• Law enforcement and customer service

• Crimes of distraction

• Terrorism

• Crime prevention through environmental design

• Media relations

• Foreign language skills

• Anger management

• Transportation security issues

• Tourism crowd control issues

TOPPs units differentiate themselves from typical law enforcement by how they judge success. Classical police departments judge success by the number of crimes solved. From this perspective, policing tends to be more reactive than proactive. TOPPs units, on the other hand, are encouraged to count success not by the number of crimes solved but rather by the number of crimes prevented. Because travel and tourism is a composite industry, TOPPs units must reflect the industry’s varied nature. Although no two TOPPs units are alike, most of them have to deal with at least six major tourism areas. These are:

• Visitor Protection. Tourism surety assumes that security professionals and police will need to know how to protect visitors from themselves, from locals, from other visitors, and even from less than honest staff members. Tourism security and safety experts should consider the needs of less-seen employees, such as cleaning staff and hotel engineers, and they must seek to ensure that site environments are both attractive and as secure/safe as possible.

• Protection of Staff. It is essential that the industry demonstrate to its employees that it cares about its staff. Travel and tourism is a service-oriented industry, so it cannot afford low employee morale. When staff members work in crime-ridden environments or are subjected to multiple forms of harassment, morale soon begins to drop, and then the customer receives lower levels of service. Tourism is a high-pressure industry and it is all too easy for staff members to be abused or for tempers to flare, which leads to a hostile work situation.

• Site Protection. It is the responsibility of tourism surety specialists to protect tourism sites. The term “site” is used loosely and can refer to any physical place, from a place of lodging to an attraction or monument. Site protection must take into account both the person who seeks to do harm to the site, as well as the careless traveler. For example, vacationers may simply forget to care for furniture, appliances, or equipment.

• Ecological Management. Closely related to, yet distinct from, site security is the protection of the area's ecology. In this text, ecology not only refers to the physical environment, but to the cultural environment also. No tourism entity lives in a vacuum. The care of a locale's streets, lawns, and internal environment has a major impact on tourism surety. It behooves specialists in tourism surety to protect the cultural ecology of an area. Strong cultures tend to produce safe places. On the other hand, when cultures begin to decay, crime levels tend to rise. Protecting the cultural ecology, along with the physical ecology, of a locale is a major preventative step that tourism surety professionals can do to lower crime rates and to ensure a safer and more secure environment.

• Economic Protection. Tourism is a major generator of income on both national and local levels. Consequently, it is open to attack from various sources. For example, terrorists may see a tourism site as an ideal opportunity to create economic havoc. In opposition to terrorists, criminals often do not wish to destroy a tourism locale; instead, they view that locale as an ideal “fishing” ground to harvest an abundance of riches. A philosophical question that has still not been resolved is, Do law enforcement agents and tourism security professionals have a special role in protecting the economic viability of a locale so as to provide tourism with extra levels of protection?

• Reputation Protection. We only need to read a newspaper to realize that crimes and acts of terrorism against tourism entities receive a great deal of media attention. The classical method of simply denying that there is a problem is no longer valid and can undercut a tourism locale's promotional efforts. For example, the Natalie Holloway case in Aruba in 2005 cost the island not only millions of dollars in lost tourism revenue, but also prestige and reputation. When there is a lapse in tourism security, the effect is long term. Some of the consequences to a locale's reputation may include the locale's moving from upper- to lower-class clientele, the need to drop prices, the general deterioration of the site, and the need for a major marketing effort to counteract the negative reputation.

Summary

Travel and tourism have undergone historic changes. In this chapter, we see an overview of travel and tourism and the interacting role that safety, security, and surety has played in one of the world’s largest industries. The chapter emphasizes the concept of leisure and shows how our modern concept is based on a Biblical premise, of rest on the seventh day. The chapter touches upon public perceptions of tourism security and safety and reality and it emphasizes the difficulties faced by a security professional, whether in the private or public sector. The chapter also underlines the financial and social challenges that face the tourism security practitioner.