Risk and Crisis Management

Introduction

On the third Monday of every April, the city of Boston, Massachusetts, holds its traditional marathon. April 15, 2013 would seem to have been just another Monday in Boston. The day dawned without any bad expectations, but suddenly, toward the marathon’s end, a day of sport became a day of tragedy. Struck by two bombs, allegedly planted by two brothers in an act of terrorism, three people lost their lives and almost 200 people were injured, with some even losing limbs. The events of that day caused the city of Boston to virtually shut down. Hundreds of thousands of people’s lives were impacted, and the city of Boston, along with the state of Massachusetts, lost millions of dollars in sales and tax revenue.

The 2013 Boston Marathon tragedy is a significant lesson in tourism risk management. It teaches us the importance of risk management and its limitations. The tragedy also reminds us about the consequence of having a crisis plan to handle a situation when a risk becomes a reality, and a risk management plan must become a crisis management plan.

Of course, Boston is not the only city to hold major sporting events. Sports tourism and event tourism are big businesses. For example, the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, will soon be hosting some of the world’s largest events, most notably the FIFA World Cup in 2014 and the Olympic Summer Games in 2016. These events will attract thousands of people from around the world, while millions more will watch from the comfort of their homes. What happens in Rio during these events will be broadcast across the globe. Risk, however, does not only refer to tourism events. All tourism carries elements of risk, from transportation, to hotel safety and security, to alcohol consumption.

This chapter deals with two essential topics within tourism security and safety: that of risk and crisis management. There is also a special section dealing with the risk/crisis continuum and how it pertains to terrorism and tourism.

Risk Management

One noteworthy problem with the term “risk management” is that it lacks a common definition. One reason for this lack of commonality is that the term “risk” has different meanings in a variety of fields. For example, if we consider the concept of risk simply in the field of finance, then we soon discover it covers a wide variety of subfields. Note that the Northrup Grunmann Group lists the following forms of financial risk:

• Market risk: The risk that the value of your investment will decline as a result of market conditions. This type of risk is primarily associated with stocks. You might buy the stock of a promising or successful company only to have its market value fall with a generally falling stock market.

• Interest rate risk: The risk caused by changes in the general level of interest rates in the marketplace. This type of risk is most apparent in the bond market because bonds are issued at specific interest rates. Generally, a rise in interest rates will cause a decline in market prices of existing bonds, while a decline in interest rates tends to cause bond prices to rise. For example, say you buy a 30-year bond today with a 6% annual yield. If interest rates rise, a new 30-year bond may be issued with an 8% annual yield. The price of your bond drops because investors aren’t willing to pay full value for a bond that yields less than the current rate of interest.

• Inflation or purchasing power risk: The risk that the return on your investment will fail to outpace inflation. This type of risk is most closely associated with cash/stable value investments. Thus, although you may think a traditional bank savings account is relatively risk free, you actually could be losing purchasing power unless the interest rate on the account exceeds the current rate of inflation.

• Business risk: This is the risk that issuers of an investment may run into financial difficulties and not be able to live up to market expectations. For example, a company’s profits may be hurt by a lawsuit, a change in management, or some other event.

• Credit risk: For bonds, this is the risk that the issuer may default on periodic interest payments and/or the repayment of principal. For stocks, it is the risk that the company might reduce or eliminate dividend payments due to financial troubles.

When you invest internationally, you also face additional risks:

• Exchange rate risk: This is the risk that returns will be adversely affected by changes in the exchange rate.

• Country or political risk: This is the risk that arises in connection with uncertainty about a country’s political environment and the stability of its economy. This risk is especially important in emerging markets. (“What are the different types of risk?”, 2013)

Each one of these areas for risk has a specific meaning in the world of finance. We can say the same in most fields, and this multiplicity of meanings holds true in the worlds of tourism and event management.

Why Analyzing Tourism Risks is Difficult

Because tourism is a composite industry, tourism and events are open to a wide variety of risks. Yet, there is no one standard for determining overall risk. Instead, tourism is composed of a series of subevents or potentials, and each one has its own set of risks. For example, a tourism business must face the interaction of weather-related risk with a number of other semi-related risks. So, an outdoor event may have to deal with the risk of too much heat, which produces the additional medical risk of heat exhaustion. Below is a very short list of primary and secondary risks that different factions of the tourism industry face:

• Fire

• Health concerns

• Terrorism

• Travel dilemmas

• Weather

Each one of these principal risks has numerous subrisks, each possibly interacting with one another. Within this perspective, a pure mathematical formula or quantitative breakdowns describing risk must be balanced with qualitative analysis. Even when we combine both the qualitative and quantitative analysis of risk, we still lack clear-cut delineations. To illustrate, the military’s use of biochemicals, or other forms of terrorism, means that there is a strong possibility of crossovers between issues of health and security, which causes an interaction between these two types of risk.

In each of these cases, the tourism professional must be aware that the risk potential is ever ubiquitous. Brazilian scholar Gui Santana has noted that crises in the tourism industry can take many shapes and forms—from terrorism to sexual harassment, white-collar crime to civil disturbances, a jet crashing into a hotel to cash flow problems, guest injury to strikes, bribery to price fixing, noise to vandalism, guest misuse of facilities to technological change (Santana & Tarlow, 2002).

Tourism risk managers must be aware of not only a single crisis, but also any combination or crossovers of crises.

As in all fields, risk management is based on a series of assumptions. Risk management is stochastic (probabilistic) in nature. Below are some of the key assumptions that support the field:

• There is no person, place, thing, or event that is 100% free of risk. If human beings can design it, then there is a human being or group of human beings who can destroy or harm it.

• Risk management relies heavily on statistics by utilizing statistical data analysis. The better the data are, the lesser the chance of failure. Yet, no matter how good the data are, the element of surprise and failure is ever present.

• In the field of tourism risk management, the risk manager must be keenly aware that to travel is to be insecure. In today’s world of travel, the traveler knows that he or she is often not in control.

• There are different levels of acceptable risk within the sociopsychological range of tourists and visitors. This means that certain people can accept a higher level of risk than others. How risk is managed depends as much on the clientele as on the risk itself.

• Many guests assume that they can leave their safety and security in the hands of the risk manager and/or security staff.

• As world tension mounts, the demand for risk management increases.

• In risk management, as in tourism, there is no distinction between security and safety. As will be seen later in this chapter, a failure in either category, or a crossover between categories, will result in a ruined vacation, or worse.

• The further we travel from a crisis, the worse the crisis seems. The further we are from a crisis, the longer it lasts in the collective memory. Thus, the protection of a tourism entity’s reputation is essential.

Crisis Management

Just as there is no one definition of risk management, there is no one definition for emergency and/or crisis management. We can say, however, that the two are interrelated. Risk management is always proactive. Crisis and emergency management are reactive by nature in that they react to a crisis rather than act to prevent it. David Bierman defines a tourism crisis as “a situation requiring radical management action in response to events beyond the internal control of the organization, necessitating urgent adaptation of marketing and operational practices to restore the confidence of employees, associated enterprises and consumers in the viability of the destination” (2003, p. 4).

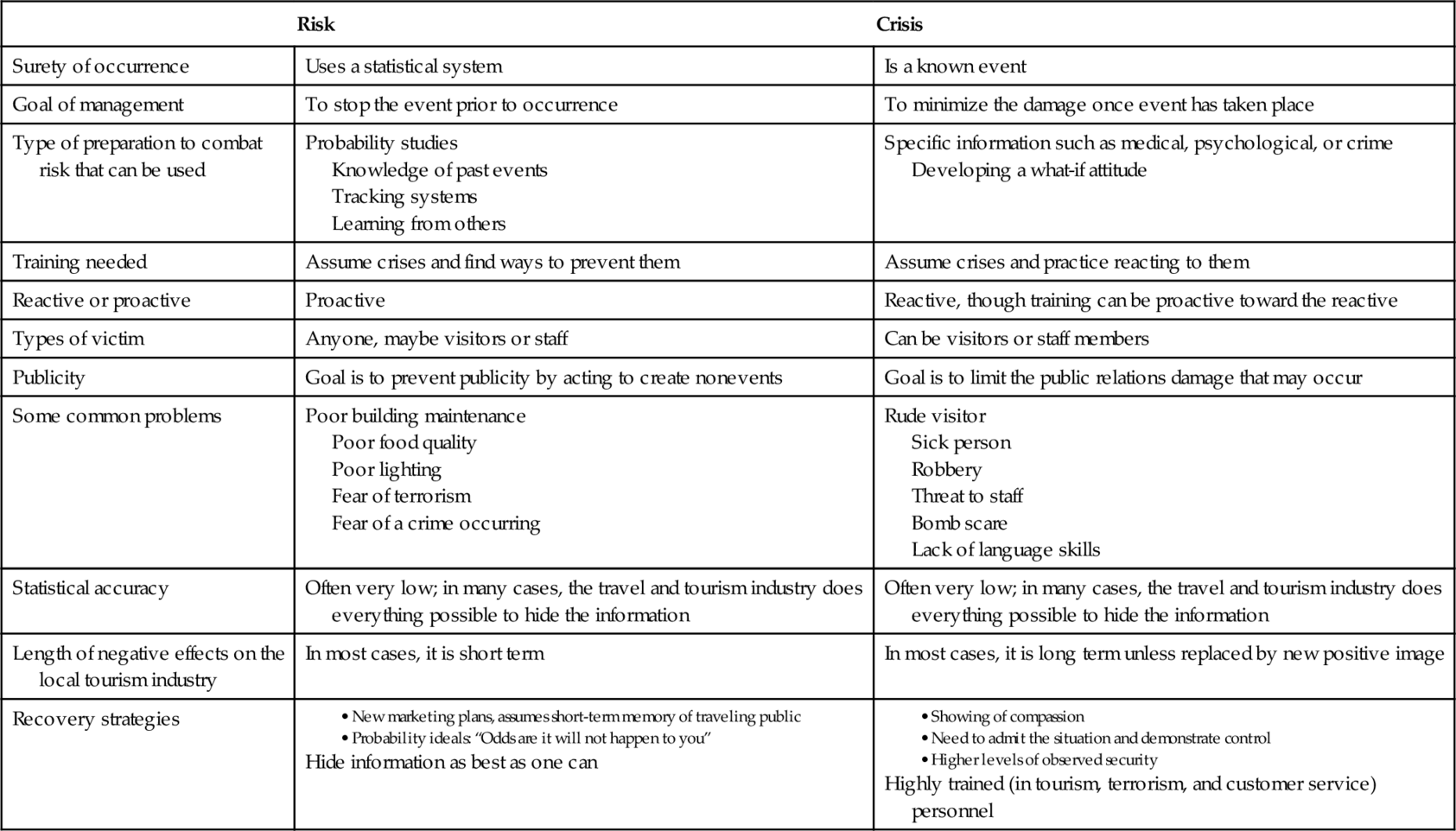

It will soon be discussed that risk and crisis management may be defined as two sides of the same coin. Table 4.1 delineates some of the most important differences between risk and crisis management.

Table 4.1

Some Basic Differences between Crisis and Risk Management

Thus, the best way to avoid a crisis or an emergency is through good risk management. Just as there are many forms of risk, there are multiple types of crises.

It is the risk manager’s task to prevent a crisis from occurring. However even the best risk management cannot prevent all crises. It therefore behooves a risk manager to also understand the types of crises that may occur.

Unlike risk (an ever-present potential), crises only become crises when they are known and publicized. Below is a listing of some of the major tourism crisis categories:

• International war and conflict

• Specific act of terrorism

• Crime wave or a well-publicized crime

• Natural disaster

• Health crisis

• Corruption and scandal

This list is far from inclusive and is meant only to provide ideas for the risk manager. It is the job of the risk manager to imagine the potential crisis that may impact his or her particular situation and then how he or she will transition from risk manager into crisis manager.

Crises can come in various forms. In the space below, list five of the most likely crises to impact your tourism location. Some examples may be (1) illnesses, (2) acts of violence, or (3) building crisis. Then, list one or two ways in which you are or should be prepared to face this crisis.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Performing Risk Management

Risk management plans are developed from data that is collected. Whether you are the risk manager at a hotel, restaurant, attraction, or event, there are certain pieces of data that you must know in order to develop a risk management plan. Among these are:

• How many people come under your “protection”? There are several substantial differences for when there are 1,000 people versus 10 or 20 people who need to be given immediate care. Even in a hotel, there is the number of people who are staying in the hotel as guests, as well as the people attending some of the hotel’s secondary components, such as its restaurant, convention center, parking spaces, etc.

• Where are the building’s strengths and weaknesses? How many ingresses and egresses are there? What is the building’s construction, and can it withstand physical problems such as earthquakes or hurricanes?

• What is the demographic makeup of the people you are serving? The type of person who you serve is a major part of risk management. A senior citizens’ convention may have different health needs compared to college spring break. As such, the types of populations served impacts every part of your risk management plan. Also, it is essential to know if you serve different population cohorts on a continual basis.

What You Need to Know as a Risk Manager

It is almost impossible for human beings to divide their personality from the jobs they are doing. Therefore, it is essential to know what your personality strengths and weakness are. Which issues push your buttons, which ones are easier to deal with, and which issues are you simply better off just walking away from? Because tourism risk management deals with people, it is important to realize that we all deal with certain personalities better compared to other personality types. As a risk (and/or crisis) manager, it is essential that you know which personality types provoke you or cause you to think in a less than professional manner? With what personality types are you compatible, and with which types do you not work well? Take the time to assess the following:

• Your personal strengths and weaknesses

• What your boss, the public, and the media expect of you

• The assumptions you make about your staff

A Risk Management Model

There are multiple equations employed for risk management. Each one has its own strengths and limitations. The model found below is one of many. What makes this model work is that it is simple and it can be updated easily. The model assumes three major concepts about risk:

1. There is no such thing as a 100% risk-free environment.

2. The risk manager will never truly have a sufficient number of resources for risk to be eliminated.

3. The risk manager then must determine what is an acceptable risk and what is not.

Below is a five-step plan on how to determine risk for your tourism entity. There are no right answers here, only guidelines to help you determine what your risks are and how deep their consequences may be for your particular tourism business.

Step 1

In step 1, list every possible risk that your event or locale may have to face. Some examples are:

• Murder

• Riot

• Gang violence

• Crime of distraction

• Sexual assault

• Vandalism

• “Con” game

• Prostitution or public nudity

• Purchases of illegal drugs

• Natural disaster

• Food poisoning

Note that you might consider some of the items above as irrelevant to your situation, but you should still list them anyway. There may actually be more relevance than you first believed, and if there is no relevance, then you can eliminate the issue.

Step 2

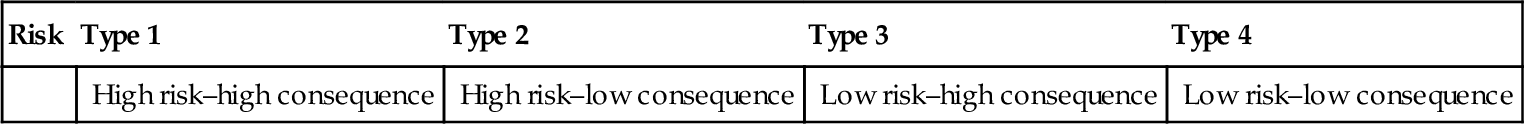

Divide the listed possible risks, that is, things that can go wrong, into one of four categories:

• Category 1: Likely to happen and the consequences are grave

• Category 2: Unlikely to occur, but should the risk materialize, the consequences would be grave

• Category 3: Likely to occur but the consequences are not grave

• Category 4: Unlikely to occur, but should the risk materialize, the consequences would not be grave

You can place these in boxes such as in Table 4.2.

Step 3

Rank the incidents receiving your highest priority as category 1, followed by category 2, category 3, and finally category 4. In reality, category 4 is a totally acceptable risk; using resources to protect your property against a category 4 would be a waste of resources.

Step 4

Tourism is as much about perceptions as it is about realities. For this reason, the tourism risk manager must always consider negative publicity as a risk factor. Once the categories above are established, then they must be measured against the ever-present risk of negative publicity.

Classify each risk stated in step 3 along the following lines:

• Likely to create a great deal of ongoing negative publicity

• Likely to create a great deal of negative publicity of a short duration

• Likely to create some ongoing negative publicity

• Likely to create minimal amounts of negative publicity of a short duration

Step 5

Negative tourism events tend to have “after-lives.” In some cases, good marketing efforts are successful in restoring the tourism location’s reputation, so the public tends to forget about the negative event fairly quickly. In other cases, the negative event takes on a life unto itself, becoming a part of public memory. Thus, risk in tourism must be seen not only as the potential for a negative event to occur, but also the length of time that it lives in the public’s memory. For example, except those people who are directly impacted by the tragedy, negative events that are acts of nature tend, in general, to be forgotten rather quickly. On the other hand, events that are deliberate acts usually last for a greater amount of time in the public’s memory.

Determine if a particular act is one that will reside in the public’s memory for a short or long duration. The longer the duration is, then the greater the risk. To accomplish this task, create a 1–10 index, with 1 being the lowest and 10 being the highest, then rank each one of the sample questions below.

2. Is the risk of a tourism tragedy an issue of weather?

3. Is your location easily accessible to the media?

4. Are there national or international correspondents located in your area?

5. Is your area a center of economic activity?

6. Is there a risk of multiple deaths that will be reported?

7. Do you have a national or international icon in close proximity?

Add your scores and divide by seven. The higher the score is, the greater the risk of tourism tragedy after-life.

Moreover, William Foos (Source: From speech given at Las Vegas international Tourism Safety and Security Conference, May 2013) has developed a series of risk analysis steps that include:

• Step 1: Define your tourism assets (both tangible and intangible)

• Step 2: Define consequences and establish benchmarks. Among these are consequences to life, property, reputation, and legal liabilities

• Step 3: Rate the consequences of the risk vis-à-vis your assets, services, reputation, etc.

• Step 4: Identify your business’s vulnerabilities

• Step 5: Develop countermeasures to the threat

• Step 6: Determine opportunities within the threat

• Step 7: Evaluate the risks from a qualitative perspective

• Step 8: Perform a quantitative evaluation of the risks from both a safety and security perspective

• Step 9: Rank the risk factors

• Step 10: Deal with the risks according to the risk level or ranking

Risk Management Guidelines

Every risk manager needs to have a stated set of guidelines. The following self-analysis is not meant to be exhaustive, but, rather, it allows you to begin thinking about the questions that you need to ask. Never begin a risk management plan without asking yourself the following:

• Do you know your vulnerabilities?

• Do you have a full set of plans that cover what to do before, during, and after a crisis?

• Have you set up a team to develop crisis plans?

• Does your plan distinguish between natural, criminal, fire, and terrorism crises?

• Have you developed a plan that has immediate action steps and unique considerations for such travel and tourism crises as:

• Act of terrorism at a hotel?

• A biochemical attack?

• Civil unrest?

• Earthquake?

• Fire?

• Flood?

• High-profile kidnapping?

• How will you be notified of a crisis?

• How will you notify others?

• Is there a plan to take immediate action?

• Is there a tourism crisis team in place?

• Is there a plan to deal with special tourism needs, such as foreign-language issues, notification of relatives abroad, and shipment of bodies to a foreign destination?

• Have you developed a set of crisis guidelines and reviewed them with every employee? Do you have guidelines to cover almost every aspect of the guest’s visit, including security? Look at these details:

• Type of lighting used in parking lots and along paths

• Policies concerning single women travelers and/or travelers who need extra security

• Employee background checks

• Special security instructions for those working at ticket booths and entrances to festivals

• What to do should a crime or accident take place

• Do a regular review of fire safety procedures. For example, it is important for all employees to know what to do in case of a fire. Some of the issues that should be touched upon include:

• Smoke. Many employees know that smoke doesn’t necessarily mean there is a major fire. Their prime objective should be to evacuate the site or isolate the fire at the first sign of smoke. Smoke accumulates at the ceiling. If exit signs are at the ceiling, then will they be seen during a fire? Do employees know that fresh air for breathing is near the floor?

• Panic. How to handle panic and how not to panic. People who panic rarely save themselves or others. The more information that a guest or employee has, the less likely they are to panic.

• Exits. Make sure guests and employees know where the exits are located. This is especially important in enclosed visitor or information center areas. We can almost be sure that the exit will be needed when the guest is least prepared. It is important that multilingual signage provides evacuation instructions.

• Have visible guards. Contrary to what some tourism professionals may believe, professional security guards are greatly appreciated because they make guests feel secure. This sense of security is especially true for female guests and visitors from foreign lands. If trained properly, then professional security guards do not hurt profits, and they can add to a locale’s bottom line. Festival managers should always do a spot-check of their guards to make sure that they are well trained and not asleep on the job.

• Do a full background check on the criminal history of all employees. Find out if a person has an arrest record.

• Get to know the people who work at local police departments and hospitals. Often, police and medical officers can point out errors and easy ways to correct problems. It is much cheaper to avoid a crisis than have to deal with the crisis after it has occurred.

• Have a clear policy regarding types of keys and who controls them.

Alcohol and Drugs and Tourism Risk

An area of tourism risk management that permeates through many parts of the tourism industry is the abuse of alcoholic beverages and illegal drugs. These substances can lead to another series of problems ranging from sexual assault to death at the wheel. Therefore, it is essential for the tourism risk manager to know the local laws and the establishment’s policies concerning alcohol and drug usage. In most places, the law handles most of your drug policies, but alcohol is a different matter. Here are some guidelines to consider when developing a policy regarding alcohol.

• Is food always served with liquor? If not, why not?

• What types of foods are served? Do you emphasize high-protein foods?

• What do you do if someone becomes intoxicated?

• How do you stop brawls or physical violence?

• Are glass objects allowed to be used?

• Are all your bartenders licensed and vetted?

• Do you have as a standard policy that all alcoholic incidents are to be documented?

Developing a Tourism Risk Management Plan in an Age of Crime, Gangs, and Terrorism

The job of a risk manager in tourism is not easy. Most tourism-oriented risk managers must deal with issues of safety and security, or a combination of both. There are issues of fire and smoke safety, food safety, and issues of crime, such as robbery and assault. In an age of terrorism, these two fields tend to merge. For example, the risk manager will need to know if a food-poisoning incident came about due to tainted food or an act of terror. Are drug sales merely an illegal act, or is the sale of drugs a way to fund an act of terrorism? This merging of the criminal with the political means that risk managers’ jobs are even more challenging than they were in the past. Despite these challenges, there are certain basic principles that underlie all tourism-oriented risk management plans. Among these are:

• Nothing in this world is totally free of risk. Like most of the public, tourists, industry leaders, the media, and tourism business stakeholders all want to believe the tourism industry can be made 100% risk free. The reality, however, is that we live with continuous risk, so there are no guarantees in life.

• Risk managers will never have enough manpower or money to prevent all risks from occurring. Tourism risk management must then be seen as a game of probabilities. Because no risk management plan can eliminate all risk, the only alternative is to decide what is and is not an acceptable risk. Acceptable risks are those that are considered the least probable of occurring, so they do not warrant resource expenditure.

• Tourism risk managers must deal with people who behave differently than when they are at home. Tourists are more likely to panic, they often have higher levels of anxiety, they have demonstrated lower levels of common sense, and they tend to enter into psychological anomic states. Consequently, the risk manager who works in the world of tourism must consider a highly unstable public when developing an overall risk management plan.

• Risk managers in tourism must never forget that they have to handle risk while at the same time provide excellent customer service. Tourism is just an activity by choice. Even during terrorism incidents, visitors are still guests, and they consider themselves as such. This makes risk management all the more difficult because risk managers are well aware they cannot take precautions that drive away business.

• The risk manager must always be aware of world events, even when these events appear to be distant from where he or she may be working. In an interconnected world where the public is exposed to a continuous 24-hour news cycle, people in one part of the world could feel the tensions in another part of the world.

• Tourism centers are not isolated from the community. This means that the risk manager must worry about what occurs on his or her property, as well as what occurs throughout the community in which the tourism entity is located. Risk in tourism involves a great deal more than mere property protection. For example, issues of weather impact the entire community, along with illnesses ranging from influenzas to pandemics. The risk manager can never forget that the employees of a tourism business are part of the local community. What impacts the community also impacts the tourism entity’s customers and staff.

• Risk management is also about the law of unintended consequences. To illustrate, electronics are wonderful, but they are only as good as the person operating them. With the rise of electronic and computerized technology, some risks are reduced, but at the same time, new risks develop. New forms of rationalizations do not mean less risk but merely different risks.

Some Examples of the Interaction Between Issues of Safety and Security in the World of Tourism

As noted previously, tourism risk managers must deal with the fact that there are numerous interactions between the local population and their client/guest population. In the post-9/11 world, the clear-cut distinctions between issues of safety and security have blended into new challenges. Below are just a few of the many security–safety blended challenges arising in the age of terrorism and tourism, as well as some of the necessary countermeasures.

Drugs, Tourism, and Terrorism

The world of drugs has become one of the great challenges for many individuals involved with tourism. There was once a time when tourism risk managers and law enforcement only had to deal with illegal drug use and the occasional drug dealer. This age of “comparative innocence” came to its conclusion when gangs entered into the illegal narcotics industry and began turf wars.

In the early years of the twenty-first century, the line between terrorism and crime became increasingly blurred. This blurring began to impact tourism when turf wars entered into the world of tourism, which occurred in a variety of ways. Among these were:

• The seeking of drugs by tourists. Tourists who believe that they are merely using an illegal substance may also be aiding and abetting worldwide terrorism.

• The destruction of tourism security due to violence stemming from those areas of the world dominated by drug trafficking. The violence often produces secondary impacts, including:

• Loss of reputation due to violence in cartel-dominated areas

• Lowering of customer service in cartel-dominated areas.

• The realization that risk managers do not know whether law enforcement officials and other first responders have been “bought” by the drug cartels. The Spanish saying “plata o plomo” means the police officer has been given a choice: either accept the money from the cartel and be “bought,” or you and your family will become victims of violence. In places in which cartels have come to dominate society, it is no longer valid to assume that police officers and private security tourism experts have high degrees of integrity and are loyal to the rule of law and order.

• The potential lack of integrity causes tourism risk managers to assume that working with law enforcement adds risk rather than diminishes it.

Ways That the Illegal Drug Trade Present Challenges to Tourism Risk Managers

Locations where there is a high degree of illegal drugs tend to have security problems. Below is a listing of some of the negative results of illegal drugs on tourism centers, along with the additional risks they pose:

• Kidnappings (especially business travelers held for ransom)

• Loss of tourism reputation resulting in the potential loss of travelers, which leads to lower room rates and the potential loss of foreign investors

• Potential for negative crime images that spread easily on the Internet and in social media

• Loss of confidence in protection services, and even in the government itself; higher levels of corruption translate into higher levels of risk that must be managed

The Risk of Food Safety in Tourism

Tourism depends on a safe and reliable food supply. Tourists and visitors cannot often go to local markets to buy food supplies, so they usually depend on restaurants or other public places to purchase food. This perhaps may be the reason that no industry in the world is as food dependent as tourism. Commercial eateries, whether they are street vendors or fine restaurants, are often the method by which most travelers eat. Food is not only an essential part of travel, but it is also one of its many pleasures. Travel affords the visitor new culinary opportunities. Food safety is much more than making sure that no one is poisoned. In this period of mass travel and tourism, food is an essential part of the total travel experience. Food is linked with a tourism experience’s reputation, whether it is on an airline, on a cruise ship, at a convention, or at a public eating establishment.

Food supply chains in the modern world are highly complex systems. With such high levels of complexity, it should come as no surprise that there are food problems. These can range from outbreaks of salmonella to food contamination. Although tourism risk managers are not expected to be specialists in food safety or presentation, they do need to be aware that food safety issues are much more involved than making sure the mayonnaise is refrigerated. The U.S. Congressional Research Service (CRS) for the Library of Congress published a major paper on agro-terrorism. The CRS defined “agro-terrorism” as a subset of bioterrorism in which diseases are introduced into the food supply for the expressed purpose of creating mass fear, physical harm or death, and/or economic loss. In today's global economy, tourism entities import foods from around the world. This implies that an agro-terrorism attack on one continent can destroy a tourism industry on another continent.

In fact, food safety and tourism security have been linked for many decades. Even superficial studies of the food industry reveal that it is vulnerable on multiple levels. From food processing until its delivery to the table, food for human and animal consumption goes through a number of hands, machines, and processes. Tracing where food may have been contaminated is incredibly difficult. When we must distinguish between accidental food contamination and terrorist contamination geared toward a political purpose, the task becomes monumental. Restaurants are vulnerable for another reason: they are icons of their society. For example, it is almost impossible to separate a pizzeria from Italian culture or a croissant from French culture.

Restaurants and other eating establishments can be targeted for a number of reasons, but here are just a few:

• Most restaurant owners do not know their patrons. Thus, as public places, restaurants provide easy access and exit.

• Most restaurants in tourism areas have no idea where their clients are after they have left their premises. This lack of information means that it is difficult to track down when food poisoning occurs.

• Restaurants rarely keep records as to where participants live or how many came in a party.

• Restaurants sell “good times,” which causes low vigilance.

• Most restaurants can easily be penetrated. Often back/side doors are left open and waiters and waitresses, working for tips, may not challenge a customer out of fear of losing income.

Therefore, risk managers need to be aware of the following:

• They have an idea as to which food can produce which illnesses. No one expects every person in travel and tourism to become an expert in all of the various food illnesses, but it is helpful to have a general idea of food safety.

• They take the time to know what the major food problems and potential crises are for their area. Each part of the world has special food safety needs and challenges. Often food safety issues are dependent on the type of food served, and where the food is obtained. Does their hotel, attraction, or restaurant use local produce, or does it import these fruits and vegetables from someplace else? What type of water supply is used in food irrigation? How good are the refrigerator containers that bring meats and fish to their locale?

• They must know who is working in the kitchen and what their state of health is. The safety of one’s food is directly dependent on the health (both mental and physical) of those preparing the food that is served. It only takes one ill chef or food preparer to sicken many of the customers. Additionally, in an age of terrorism, food preparation areas invite terrorists to accomplish their primary goal of economic destruction without being noticed. A risk manager must be sure that he or she has a full record of who is preparing food, what their backgrounds are, and continuous updates on the state of their health.

• In a like manner, waiters and waitresses are a key link in the tourism food chain. Who are the waiters and waitresses? Too many people in the tourism industry choose to ignore the safety and security issues that surround these essential links within the food service industry. Because the principal source of income for these people comes from tips, they often have no sick days, health insurance, or other social protection. Consequently, they will come to work even when they are sick. This implies that the public is placed at risk due to contaminated people handling their food. For example, it is essential for all food handlers to wash their hands often and maintain the highest levels of hygiene possible.

• Risk managers need to sensitize staff to food allergies. As stated previously, food can be contaminated through illnesses or a malevolent act. Yet, there are also a growing number of people suffering from food allergies or with special dietary needs. Unfortunately, too many staff either do not care or are ignorant of the fact that a mistake can be fatal. While no staff person can be expected to know every possible food allergy, it is essential that they be trained not to assume or guess. In case a customer indicates that he or she is allergic to a specific condiment or food substance, it is imperative that restaurants, hotels, and other food providers know how to obtain precise and accurate information.

• Risk managers must be sure that trash is deposited in a way that does not harm the environment. Food safety is not only about the quality of what is served and how, but also about the disposal methods for unused foods. Too often food is left outside in plastic bags that produce foul smells and are easily broken into by animals. Poor disposal techniques can lead to environmental hazards, eyesores for communities, and health hazards.

• If the tourism entity uses an outside catering service, then the risk manager must understand who and how that caterer operates. Many tourism events are catered affairs. However, people in the tourism industry often have no idea who works for their caterers, whom they employ, or what their backgrounds are. Caterers should come under the same scrutiny as hotels and restaurants.

Fire and Tourism Safety

One of the great threats to any tourism entity, whether it is an attraction, hotel, or restaurant, is the issue of fire and fire safety. Visitors are notorious in being lax about fire and fire codes, and many tourists and visitors simply do not believe that a fire will impact their lives. Consequently, the denial of fire is one of the greatest risks that a risk manager has to confront.

Dr. Richard Feenstra is an expert on fire safety. He emphasizes the fact that risk managers need to work closely with the local fire department. For instance, referring to event management, Feenstra notes that when an event exceeds 300 people, a permit for temporary assembly is required in many U.S. locales. Cooking, fireworks, and even the simple use of candles may require an event planner to apply for a permit (Source: From Speech given at Third biannual Caribbean Tourism Security Conference, June 2012 and from 2012 personal interview).

Fire departments do more then merely put out fires. Fire departments are often the permit providers, so a mistake in one’s permitting can result in denial of access, angry guests, and loss of money.

Risk managers must be constantly aware of the threat of fire, as well as the consequences of not following fire department rules. When it comes to fire prevention, consider the following:

• Have a full inspection by the local fire department and make sure that you meet all fire department regulations, codes, and/or ordinances.

• If you are holding an event, then submit a request for authorization as early as possible. The earlier the request is made, the better its chances with the bureaucratic procedures. Also, if something needs to be changed, then there is no last-minute crisis.

• Conduct an inspection before the fire inspector arrives. While the risk manager may not be aware of exactly when the inspector is going to arrive, it is a good idea to walk through the locale or event in order to check for the following: fire extinguishers are charged and have inspection tags, exits are not locked or blocked, exit signs are properly lit, there are no trip hazards, or if any other obvious safety concerns exist.

• Get agreements in writing. It is all too easy to misunderstand or mishear a fire inspector. The best way to avoid the risk of fire is to have the fire professional put everything in writing and then follow his instructions.

• Risk managers should never be afraid to admit that they do not know something. Most fire inspectors welcome honest questions. Although the risk manager is not expected to be an expert in everything, he or she is expected to contact and work with the people who have the expertise in a specific field. Most fire inspectors want to help, and they are happy to explain why a code or regulation is in place. If there is a psychological breakdown between the risk manager and the expert, then it is the duty of the risk manager to find someone with whom he or she can develop a good working relationship.

• Know what the standards of care are, especially in deadly fields of endeavor such as fire safety. Risk is not only physical it is also legal. This means that a good risk manager knows the standards of care that are expected. A good risk manager not only consults a fire expert in the technicalities of something such as fire safety, but also a legal expert who can explain the legal issues involved.

Terrorism and Tourism

As previously noted, risk management is a difficult term to define, and risk management in an age of terrorism is almost beyond the scope of definability. The term terrorism is not easy to define, and to complicate matters further: “There is no general consensus as to who is a terrorist or what the definition of terrorism is” (Tarlow, 2005a; 2005b, p. 79). Until now, no one has created a mathematical system that can accurately predict terrorist attacks. The somewhat random nature of terrorism attacks means that risk managers must consistently expect the unexpected. What we do know is that tourism has been a magnet for terrorist attacks. The reasons for tourism’s attractiveness toward terrorism are numerous:

• Tourism provides soft targets. For example, few hotels make a person pass through a metal detector before entering, and many hotels were built in an age of innocence, in which the architectural goals were convenience and/or beauty, rather than security.

• Tourism provides opportunities for mass casualties. Given that tourist locations are often places of gathering with only a few people thinking about security issues, they provide excellent targets for terrorists who desire to murder or harm large numbers of people with relative ease.

• Tourism provides iconic settings. Icons are places that symbolize something within the local, national, or world community. For example, the Eiffel Tower is not only a symbol of Paris, but it is a structure that is part of the world’s heritage. Any attack against an icon will receive a great deal of publicity, which puts fear into the hearts of many.

• Tourism is big business. Terrorists attempt to harm or murder innocents, and they seek to destroy economies. Because it is such a large industry, the impact of tourism is felt within the total economy. In the case of 9/11, the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York caused millions of dollars’ worth of loss not only for New York City, but also the global airlines industry, which came to a halt. Terrorists understand that airlines use large hubs; if a hub locale is attacked, then this will have repercussions on a worldwide basis.

• Attacks on tourism provide a great deal of publicity, and terrorism seeks publicity. Tourism centers are places where there is a great deal of media coverage. An attack against a tourism center creates an instant impact on the locale, which can lead to long-term perception consequences.

• Terrorists have the element of surprise in their favor. The risk manager has to outguess his opposition and be correct every time. The terrorist has the luxury to fail repeated times, but even his failure causes negative publicity, inconveniences, business disruptions, and forced additional expenditures or resources.

• Despite what the media may say, terrorists are not cowards. In all too many cases, terrorists believe that they are fighting for a righteous cause, and they are willing to lay down their lives for said beliefs.

• The risk manager must deal with the fact that terrorism may manifest itself in multiple formats, such as attack of food supplies, mass murder, or the introduction of drugs into a political body. In all cases, however, the terrorist hopes to gnaw away at a society with the hope of destroying its collective cohesiveness.

• Terrorists may target a wide variety of groups. Tourism is especially attractive because there is still a lingering belief that tourists are part of a leisure class that takes advantage of the working class. As such, there is often a reverse sense on the part of terrorists in which they see themselves as the true victims, while the victims of their attacks are somehow responsible for their own predicament. Terrorism then uses a form of victimization of the victim to justify its actions.

• Tourism represents many of the values that terrorism despises. Among these values are:

• The fair and equal treatment of women.

• The belief that a person should be judged by who he or she is and not by the group to which he or she belongs.

• The belief that learning about other cultures and people is a positive endeavor and should be encouraged.

• The concept that the world is a better place when we celebrate our differences. Tourism is about the celebration of the other.

• There is nothing wrong with a business making money. Terrorists tend to think of money as “dirty” and capitalism as evil.

• It is important to find compromises to situations in which there are disagreements. Terrorism takes the opposite viewpoint and rejects the notion of compromise.

Tourism, almost by definition, is the opposite of terrorism. In fact, women hold major tourism positions throughout the world. The industry is based on individuals' experiences. It is the exact opposite of a xenophobic world in which the other is despised rather than celebrated.

Tourism, Terrorism, and the Media

In the world of journalism, there is the saying, “If it bleeds it leads.” If the media like a crime story, then terrorists provide the media with a world of intrigue from bloodshed to politics. Terrorist acts often seem designed for television, and terrorists, who are often incredibly media-savvy, find ways to provide the television cameras with as many visuals as possible.

Such problems become even more apparent when there is a great deal of publicity, such as that surrounding a major sporting, entertainment, or political event. For example, in April 2013 a tourist in the city of Rio de Janeiro suffered a brutal sexual assault (“American student was gang-raped,” 2013). Although the police were able to apprehend the criminals almost immediately, the incident still created major headlines around the world, even though sexual assaults occur everywhere. The reasons for this hyped publicity had to do with Rio de Janeiro’s hosting of the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the large number of reporters stationed in Rio. A simple rule of thumb is that the greater the number of journalists in a particular place, the higher the probability of negative incidents becoming major news stories. Terrorists are well aware of this fact, especially because journalists tend to report negative stories.

This means that risk managers must hinder acts of terrorism, while at the same time develop media plans to prevent journalists from unwittingly aiding terrorism in its attempt to destroy a local tourism industry. Below are some basic suggestions on dealing with the media before, during, and after an incident.

Before an Incident

• Develop relationships with people in the media. Know with whom you can count on and who seeks only the dramatic.

• Have a secure call number and place where the media can interview you. In the case of a terrorist attack, having a “safe” media location is essential.

• Develop a media chain of command. Know who will speak and who should refer journalists to others. Have one single message.

• Have a number of press release templates ready to go and make sure that these press releases are easy to read. If the media person cannot read or understand what you wrote, then the odds are that he or she will ignore it. Use a font size that is clear, avoid jargon and/or technical words, and underline or bullet your points.

During the Incident

In actual time, this stage is the shortest, but it is perhaps the most important. This is the time when the risk manager must show leadership, not panic. He or she should demonstrate knowledge of the plan in addition to professional flexibility. During the incident be sure to:

• Take careful notes. Reporters and management, both now and later on, will ask specific questions. The more accurate facts the risk manager has, the easier his or her life will be after the incident has come to its conclusion. Do not allow the confusion of the moment to blind you to what needs to be done

• Be polite but firm with reporters. If the risk/crisis manager cannot speak to media representatives during the incident, then he or she should explain that he or she will get back to the media as soon as it is known that lives are being cared for. During the incident, the risk/crisis manager’s first priority is the safety of guests.

• When being interviewed, it is wise for the risk/crisis manager to offer the reporters a beverage because they work long hard days. It is ironic that in the hospitality industry, we often forget to be hospitable to those who report on our work. In the rare case that a reporter is hostile, a small human touch will usually soften their attitude toward you.

• Be brief. In most cases, a long explanation will be reduced to a single sound bite. For example, political candidates reduce messages to 90 seconds, with one or two phrases that can become a 10-second sound bite.

• Don't overload. It is rare that a reporter has the time to sort through a great deal of information. Most reporters have deadlines to meet. Keep your releases short and to the point.

• Be honest. The worst thing for anyone to do is to lie. It is perfectly acceptable to say you do not know, but whenever possible, follow up your “don't know” with a willingness to “find out.” When a terrorist act occurs, the phrase “no comment” sounds as if you are covering up the truth.

• Be cooperative and smile. Never forget that the reporter has the last word. When dealing with a hostile reporter, do your best to win him or her over and turn an enemy into a friend. Never pass the reporter off to a superior. He or she may well resent your attitude and just use what material he or she already has.

• Be clear and specific. Assume the reporter and the public have little or no knowledge about what they are asking. Never use tourism jargon or acronyms such as convention and visitors bureau (CVB). State the entire word. By using clear precise nouns, you lessen the possibility that your answer can be taken out of context.

• Return all media phone calls. Even if you do not wish to speak to a reporter, eventually you are going to have to speak with that person because the reporter is still going to write the story even without hearing your side.

• Do not ask the reporter to let you check his or her story. Even if he or she agrees to your request, the odds are that “something” will happen, so you'll never see the story before it goes to print. The reporter may become defensive or angry, which will result in a bad situation being made to look much worse.

The Follow-up after the Incident

Risk/crisis managers are always caught in a significant conundrum. If nothing occurs, then their superiors want to know what they are getting for their money. Yet, if something does occur then these same managers want to know why the system has failed. If an incident takes place, then the risk manager realizes there will be an investigation as to what went wrong. In reality, 100% security is a fallacy. The hope is for the risk manager’s report to identify weaknesses within the system rather than seeking a scapegoat. However, the risk manager should be prepared to protect him- or herself from being the scapegoat. Thus, he or she needs to review all notes; try to have as many complete answers as possible; and exude a nondefensive and cooperative attitude.

• Read what the reporters wrote. You may not like what you read, but you still need to do so. Even reading negative stories lets everyone know that you are not afraid to see the ways others view you.

• Maintain both a soft and hard copy of every article printed and/or a DVD of every newscast. This media library provides you with a database, and it indicates to the media that you take them seriously.

• When appropriate, provide compliments. Take the time to tell a reporter that he or she has done a good job on a story. Reporters are people too, and just like you, they also respond better to positive feedback.

• Be prepared to correct potential misinformation. Even the best reporters make mistakes. Letting reporters know that you are well aware of how accurate they have been demonstrates to the journalist that you take him or her seriously and that you expect accuracy in their news coverage.

• Invite reporters to return and show them how your recovery strategy has worked (is working). Above all, be positive. Part of every risk manager’s job is to reduce the risk for next time.

From Risk Management to Crisis Management

Although it would be wonderful if risk management could be so successful that it eliminated the need for crisis management, the reality is that every person, thing, or business will eventually have to face a crisis at some point. Thus, risk managers must also be crisis managers. An ever-present risk is the inability of the risk manager to transition from risk to crisis management. To ease this transition, the risk-now-crisis manager must change his or her mindset. People involved in risk management are concerned with the need to predict and prevent a crisis. As such, the field of risk management is always oriented toward the future tense. Crisis management, on the other hand, is about what is occurring in the present and how to deal with an ongoing situation. These two disciplines merge when it comes to the post-crisis analysis where what happened in the past is analyzed so that preventative measures can be taken to avoid (or at least, lessen) the impact of a negative event in the future. Thus, there is a consistent merging of risk management with crisis management, and then back to risk management. The risk–crisis continuum then has three stages:

1. Prevent the negative event (risk management)

2. Deal with the negative event (crisis management)

3. Analyze and learn from the negative event (crisis management)

Stage 2 often has the least duration, but is the most critical. It is the one stage where there is no time to correct mistakes. The crisis manager may only have one chance to succeed.

To begin the transition process, the risk manager must be prepared to recognize that there is a crisis. Recognition and acceptance of a crisis is not easy. Humans psychologically tend to negate a negative event. This is known as the “this-cannot-be-happening” syndrome. The faster that the risk/crisis manager can react to the new and unfolding reality, the faster that he or she can begin to take the necessary measures to control and then overcome the crisis. The risk manager must be able to change from risk to crisis management almost instantaneously.

Once the crisis manager realizes that he or she is in the midst of a crisis, it is essential to decide the depth of the crisis based on a realistic assessment. Staying grounded in reality is essential because humans have a tendency either to over- or underreact to an ongoing crisis. Risk/crisis managers are human beings and denial and panic mechanisms often play a major role in the person’s psychological stance during a crisis. Prior to the crisis, the risk manager should have developed a crisis management team. When the crisis is upon him or her, it is time to activate the team. Therefore, the crisis manager must know certain basic facts:

• How does he or she communicate with team members?

• Is there a substitute person in case the team member is unavailable?

• How does the crisis manager communicate with his or her team members?

• What redundancy of addresses, telephone numbers, email addresses is there so a team member can easily obtain the information if access to the tourism site is not possible?

Because there may be more than one crisis occurring at any given time, the professional crisis manager must have a variety of people at his or her disposal. The crisis team(s) may consist of the following professionals:

• People from media and public relations

• Members of your marketing team

• Other members of the travel industry

• State and national tourism leadership, if available

• Local tourism and hospitality leaders

• Victim assistance units

Crisis Perceptions

Earlier we spoke of how important it is to understand and to take into account crisis perception because all crises have after-lives. In crisis management, we define a crisis after-life as the amount of time the media gives a particular event attention. A crisis may have a short or long period of media attention. Usually, the longer the crisis is a media focus, the more damage it does to the local tourism sector. Crises also have the ability to “expand.” For example, instead of stating that there was a fire at a specific location, the media “expanded” the crisis to the entire community. This crisis expansion means that although other parts of the community are not in crisis, the media’s imprecision of terminology may cause collateral damage that becomes a new risk crisis. Never forget that during a crisis, geographic confusions may occur. For example, if the media reports there are forest fires in a particular part of a state or province, then the public may assume that the whole state or province is on fire. Visitors are notoriously bad at realizing the geographic limits of a crisis. Instead, panic and geographic confusion often expand crises and make them worse than in reality.

Here are some general principles when handling a crisis:

• Never assume a crisis will not touch you. Perhaps the most important part of a crisis recovery plan is to have one in place prior to a crisis. While we can never predict the exact nature of a crisis before it occurs, flexible plans allow for a recovery starting point. The worst scenario is to realize that one is in the midst of a crisis without any plans on how to deal with it.

• Always see the crisis through the visitors' eyes. All too often people tend to assume that the outsider has the same knowledge base as that of the local person. Crises often seem worse and last longer from the outsiders' perspective than from the local person's perspective.

• Do not just throw money at a crisis. Often people deal with crises simply by spending money, especially on equipment. Good equipment has its role, but equipment without the human touch will only lead to another crisis. Never forget that people solve crises, not machines.

• Never use marketing/advertising as a cover-up or an excuse. The worst thing to do in a crisis is to lose the public's confidence. Be honest and work to solve the problem, not spin it. Excuses make no one happy except those that give them.

• No one has to visit your tourism locale, so once the media begins reporting that there is a crisis, visitors may quickly panic and begin to cancel trips. Often, it is the media that define a crisis as such. Have a plan in place so that correct information can be given to the media as quickly as possible.

Crisis Recovery

Post-crisis recovery programs can never be based on one factor alone. The best recovery programs take into account a series of coordinated steps. Never depend on only one remedy to bring you toward recovery. Instead, coordinate your advertising and marketing campaign with your incentive program along with an improvement in service.1 Here are several potential strategies to deal with the post-crisis aftermath:

• Ignore the crisis and hope that no one learns about it. This strategy assumes that the less said the better. In a minor crisis, it is often a successful strategy, or if the media is willing to aid the industry by not reporting an event. The strategy breaks down when the crisis becomes a media news item and the crisis management team allows an information vacuum to occur.

• In the case of a large region, the crisis management team may want to deemphasize one region, and instead place its marketing efforts on a nonimpacted region. The problem with this technique is that in large areas, the impacted region loses twice, once from the crisis event and then by the diverting of visitors to other parts of the region or nation.

• Find industries that may be willing to partner with your community or region so as to encourage people to return. You may be able to speak to the hotel transportation or meetings and convention industries to create incentive programs that will help your community ease through the post-crisis period. For example, the airline industry may be willing to work with you to create special fares that encourage people to return to your community.

• Appeal to people’s better nature: “We need you now!” President George W. Bush successfully used this technique after 9/11 when he asked people to resume travel as a patriotic duty. Yet, the system only works if there is an emotional tie between the locale and a specific public.

• Develop post-crisis incentives. Once you recognize a crisis has occurred, determine when you will be back in business, and begin rewarding people to visit the location. You can emphasize that during this recovery stage, there are great bargains, so it is the time to take advantage of these incentives. Emphasize the need for tourism employees to maintain both dignity and good service. The last thing a person on vacation wants to hear is how bad business is. Instead, emphasize the positive. State that you are pleased that the visitor has come to your business or community. After a crisis, do not frown, but smile!

• Invite magazines and other media people to write articles about your recovery. Make sure that you provide these people with accurate and up-to-date information. Offer the media representatives the opportunity to meet with local officials, and provide them with tours of the community. Then, seek ways to gain exposure for the local tourism community. Go on television, do radio pieces, invite the media to interview you as often as it likes. When speaking with the media in a post-crisis situation, always be positive, upbeat, and polite.

• In the case of politically independent regions, offer tax incentives and other forms of economic aid to allow local restaurants, hotels, and attractions to begin the recovery process.

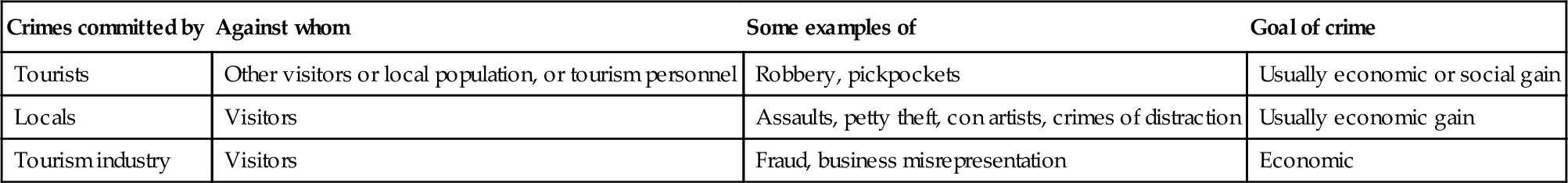

Be sure to understand which techniques should be used for various types of crises. Is the crisis medical or health related? Is it the result of an act of nature? Was the crisis created through violence? Is the crisis ongoing or a one-time event? Is the crisis a media spectacle or something that will dissolve into the historic past in a relatively short period of time? The answers to these questions often help to indicate what type of crisis action and post-crisis recovery plan you wish to employ. For example, given that a crisis can be violence related, it is of value to know these differences in today's world (Table 4.3).

Table 4.3

Types of Crisis and Their Consequences

| Crimes committed by | Against whom | Some examples of | Goal of crime |

| Tourists | Other visitors or local population, or tourism personnel | Robbery, pickpockets | Usually economic or social gain |

| Locals | Visitors | Assaults, petty theft, con artists, crimes of distraction | Usually economic gain |

| Tourism industry | Visitors | Fraud, business misrepresentation | Economic |

Source: Tarlow (2005a; 2005b, p. 96)