CHAPTER TWO

Transformational Stewardship in the Public Interest

Our case studies reinforce a premise, widely supported in the literature, that leadership is a critical element in the change and transformation process; effective “change leadership” requires special skills, which we believe are encapsulated in the concept of “transformational stewardship.” In this chapter, we first review leadership theories in general, and then more specifically change leadership theories. Second, we describe the concept of transformational stewardship and provide a list of attributes of successful change leaders. Third, we provide some illustrations from our case studies that reinforce our transformational stewardship concepts and approach.

TAXONOMIES AND THEORIES OF CHANGE LEADERSHIP

Most people feel they know what leadership is, or at least, somewhat akin to pornography, “we know it when we see it.” That has not stopped academics and practitioners from developing general theories about the “best” ways to categorize approaches to leadership. We group these taxonomies into the following six categories:

• Trait theories of leadership attempt to develop a list of defined characteristics of leadership, such as intelligence, self-confidence, decisiveness, courage, empathy, and integrity. Proponents include Stogdill (1948, 1974); Mann (1959); Lord, DeVader, and Allinger (1986); Kirkpatrick and Locke (1991); and more recently the “emotional IQ” or maturity approach of Goleman (1998) and Goleman, McKee, and Boyatzis (2002).

• The style approach emphasizes the behavior of leaders, ranking individual relationships with followers in terms of the leaders’ “concern for people” and “concern for production or results.” The Blake and Mouton Managerial Grid is one of the best known approaches of this type (1964, 1985).

• The situational approach characterizes the leader’s role along a “supportive” and “directive” matrix, based on the development level of the followers (Hersey and Blanchard 1993).

• Contingency theory—a “leader-match” approach—suggests that the type of leadership style needed depends on three factors: leader-member relations (good or poor), task structure (high or low), and positional power of the leader vis-à-vis the follower (strong or weak) (Fiedler 1967; Fiedler and Chemers 1974).

• The transactional versus transformational leadership approach is associated with James MacGregor Burns’ influential book Leadership (1978) and the work of Bennis and Nanus (1985). Transactional leadership refers to leadership approaches that focus on the exchanges (i.e., promises of rewards or threats of punishment) between leaders and followers. In contrast, transformational leadership refers to a process in which the leader and follower engage each other in creating a shared vision that raises the level of motivation for both. Bass and Avolio (1994) state that this level of motivation encompasses the following: “idealized influence”—charisma or ethical role model of the leader; “inspirational motivation”—communicating the shared vision and values; “intellectual stimulation”—for greater creativity and innovation; and “individualized consideration”—listening carefully to the needs of the followers.

• Servant leadership focuses on the follower: The leader is required to take care of and nurture the follower, while shifting power to the follower (Greenleaf 1970; Autry 2001). Other “holistic” approaches that are generally linked with a strong ethical dimension include “spiritual” leadership (Fairholm 1997; Vaill 1989b) and “stewardship” (Kass 1990; Kee 2003).

While their proponents suggest that the various leadership theories apply to organizations that are fairly static as well as to those that are undergoing change, leadership theories do not always explicitly take “change” into account. Some might argue that leadership is inherently change-oriented—that the function of management is to protect and nurture the status quo, while the function of leadership is to continually examine better ways of doing things (see, e.g., Zeleznik 1977). Clearly, some of the leadership theories, such as transformational leadership, are more change-oriented.

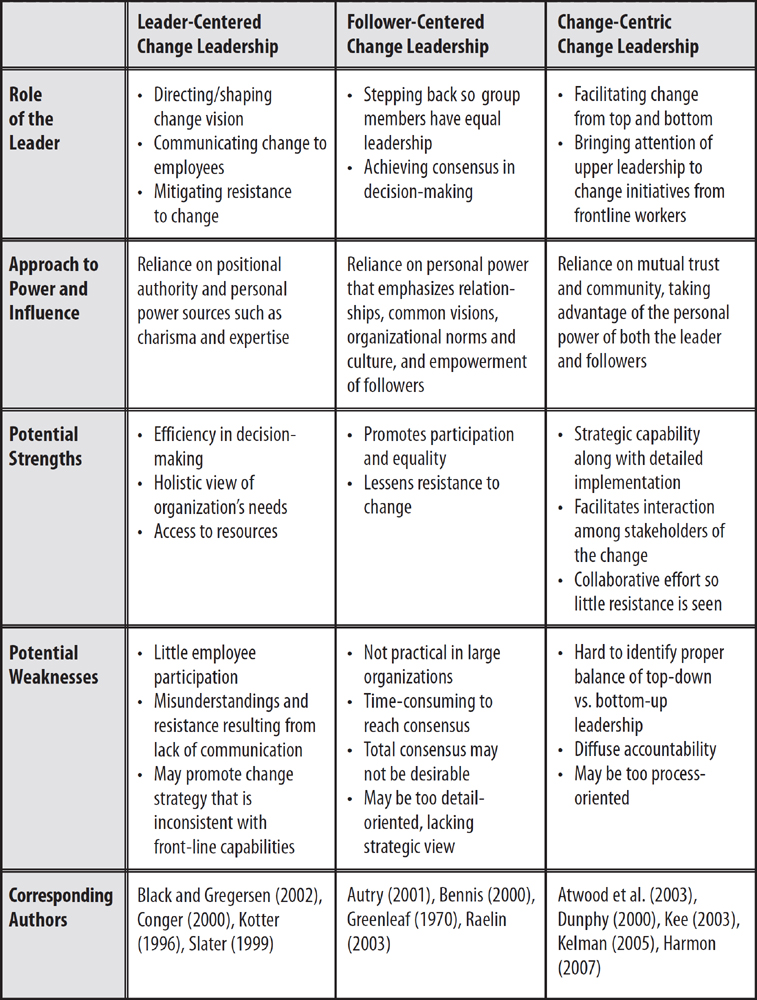

Nonetheless, issues of change leadership have spawned a whole new set of authors, many of whom have written primarily with the practitioner in mind. For the sake of discussion, we have created a taxonomy that divides the works of these authors into three models of change leadership: leader-centered, follower-centered, and change-centric leadership.

In any change effort, a public sector leader or manager must make careful use of his or her power and influence to effect the necessary change. However, the nature of the use of power and influence may be different depending on whether the change leader is leader-centered, follower-centered, or change-centric.

A leader-centered change leader is likely to focus on those aspects of power and influence that revolve around the leader’s own power sources (legitimate authority, expertise, charisma). In follower-centered change, a leader is more likely to rely on his or her indirect sources of power and influence (common vision, relationships, organizational norms and culture, empowerment). A change-centric leader is likely to rely primarily on mutual trust and community, drawing on both the leader’s and the followers’ power to achieve the needed change.

Table 2.1 provides a summary of the three approaches to change and their various strengths and weaknesses.

TABLE 2.1: Comparison of Change Leadership Models

Leader-Centered Change Leadership

Much of the change leadership literature is based on the assumption that change initiatives emanate primarily from the top leader or leaders of an organization. While various levels of employee participation may be involved, the ultimate change vision and strategy are formulated by those at the organization’s helm and trickle down through the various levels of hierarchy in a top-down approach. In this model, the success or failure of the change initiative is solely dependent upon the actions of the leader.

Charismatic leaders who initiate changes based on their personal characteristics and inspire others to follow their vision fall into this category of change leadership. A prime example of charismatic leadership is the legendary General Electric CEO Jack Welch. According to Welch, “leaders are people who “inspire with clear vision of how things can be done better’” (Welch quoted in Slater 1999, 29).

Strengths of Leader-Centered Leadership

One argument for the leader-centered framework is the assumption that the leader is in the best position to plan for an organization-wide change effort. Top leadership has the power to use the organization’s resources for the change, the ability to see the system holistically, and the authority of being in a leadership position, which legitimizes the change effort in the eyes of employees (Conger in Beer and Nohria 2000).

Kotter argues in his book Leading Change that top leadership is in the unique position of effecting change. Kotter articulates eight steps that he deems necessary to lead change successfully, including creating a sense of urgency for change, communicating the change vision, creating small wins, and embedding the change into the organization’s culture. Although these steps involve employee participation and involvement along the way, they are ultimately the responsibility of top management (Kotter 1996).

According to other change leadership authors, top leadership is also best positioned to overcome resistance to change from lower level employees by changing employees’ “mental maps,” or their current understanding of the status quo, so they are more willing to embrace the change effort (Black and Gregersen 2002). The primary goal is not to involve employees in the vision-setting stage of the change process, but instead to invite their participation in the implementation stage of the change so resistance can be mitigated.

An additional strength of leader-centered change is the efficiency it provides in decision-making. When a decisive, timely decision needs to be made, relying on the top leader to make the call can be the quickest course of action. While occasionally it may be beneficial to have input from employees in decision-making, there may not be time for such extended interaction when making a decision for change. Leaders often need to adapt to a new course quickly and effectively.

Potential Weaknesses of Leader-Centered Leadership

Although the leader-centered change strategy has many benefits, it also has several drawbacks. The first consideration is whether the organization’s culture will accept or reject the change effort. Often, organizational cultures are resistant to change and can thwart the process, through both direct and indirect means. If top leadership simply tries to push change down the ranks, the employee culture may resist and successfully sabotage the effort.

Another drawback to the leader-centered approach is the potential lack of communication between top management and those actually implementing the mechanics of the change. Kotter contends that communicating the change through repeated announcements or meetings is important to help people become familiar with the change process (1996). However, any change effort pushed from the top down has the potential to be misconstrued by those not involved in the planning. They may not have the background or full understanding of why a change is necessary and may therefore resist the change. Such a scenario is not conducive to the type of “buy-in” so many change authors (e.g., Kotter 1996) say is critical for effectively overcoming resistance and orchestrating change.

Related to the problem of buy-in is the sometimes faulty assumption that top leadership knows the one and only successful change path. However, it is often mid-level managers and frontline employees who will be charged with implementing the change effort. These hands-on individuals have experience and knowledge of details related to implementing the change that top leadership may not. If frontline workers are not included to some degree in the planning process, leaders may miss important ideas for implementing the change.

Follower-Centered Change Leadership

In contrast to the top-down approach of the leader-centered model, the follower-centered leadership framework outlines how change is accomplished from the bottom up. In this model, change is initiated from any level within the organization. Top leadership works to bring frontline change issues to the forefront and then steps back and allows lower level employees to control the change process. The idea of servant leadership is conducive to this model (Greenleaf 1977; Autry 2001).

One role of a servant leader is to delegate authority and power to subordinates in order to improve the employees’ leadership skills and abilities (Northouse 2004). In the change process, a servant leader defers to employees’ ideas and approaches in implementing the change. While this process may not lead to the exact change the leader seeks, the change that does occur is more likely to be supported throughout the organization.

Strengths of Follower-Centered Leadership

One major advantage of the follower-centered approach is its ability to lower resistance to change and encourage the feeling of empowerment among those being asked to implement the change. This deep level of involvement can lead to a consensus for change. Raelin’s idea of “leaderful organizations” (2003) is a good example of this strategy. To be leaderful is to distribute leadership roles, including the powers of decision-making, goal-setting, and communicating, throughout the entire group or team working on a change process. The focus is on fostering group dynamics that help individuals feel valued and part of the entire change effort.

Bennis argues that our society places too much emphasis on individual leadership capabilities and overlooks the value of considering everyone’s role in the organizational system. He labels top-down change management “maladaptive” and “dangerous” (Bennis in Beer and Nohria 2000, 120). For Bennis, successful organizations are those whose leaders focus on followers and encourage the expression of their opinions on organizational operations, including change processes.

By encouraging involvement and collaboration, the follower-centered approach offers the potential for increased intra-organizational communication. If everyone in the organization is a part of the change effort, then there is likely to be increased communication and collaboration, although it will take more coordinating effort from leadership to achieve this increase.

Potential Weaknesses of Follower-Centered Leadership

The main drawback of the follower-centered approach is its lack of timeliness in fostering decisions. In today’s fast-paced world, there is often insufficient time to devote to such a labor-intensive change process as the follower-centered framework requires. Developing a group to the level of a “leaderful organization” as Raelin suggests would take more time and resources than most organizations have to spare. Additionally, the emphasis on consensus building is not realistic or even desirable in all cases. Often, people cannot completely agree on a certain issue, yet a decision needs to be made to move forward.

Furthermore, while this approach may work well in a small team of six to eight people, it is not likely to be achievable or effective in a government agency with over 10,000 employees or a large nonprofit agency, such as the Red Cross. The logistics of organizing such a high level of collaboration and leadership sharing in such a huge organization are hard to fathom. Additionally, there are often legitimate reasons, such as security concerns, for restricting information within the organization.

The last major challenge to the follower-centered approach is its potential lack of strategic thinking. While those on the front lines will often know implementation details better than top management, they may not be privy to the full picture of what the change process needs to achieve on all levels. They may understand their particular team or department well, but they may not understand the full impact of how their piece fits into the larger organizational change puzzle. Also, because of the potential lack of the “big picture,” follower-centered change groups may not have the extra-organizational contacts necessary to make a change initiative successful.

Change-Centric Leadership

The leader-centered and follower-centered approaches (top-down versus bottom-up) do not offer much middle ground. Based on our research and case studies, we believe that change-centric, transformational stewardship presents an alternative and more successful approach. This model does not focus on which level of the organization should institute the change effort. Instead, what matters is finding the proper balance of topdown and bottom-up management that leads to a successful change effort.

The focus of change-centric leadership is on the successful change effort itself, not on assigning inflexible leadership roles. This is not to say that leadership is unimportant. On the contrary, the leaders of an organization serve as facilitators of change. They should strive to be cognizant of when change efforts require more initiative from the top and when the success of change efforts may hinge on allowing more employee participation and formulation of the change vision and plan. Dialogue among all levels of leadership is encouraged, but not to the extent of hindering the decision-making process.

Sometimes the top leaders in an organization will need to make change decisions, especially when external environmental pressures and resource constraints do not allow for more employee involvement. However, because change efforts in the public and nonprofit sectors are often completed over a longer time frame, more participation from lower ranks can be cultivated.

Strengths of Change-Centric Leadership

One of the major strengths of change-centric leadership is its ability to address the buyin and resistance problems associated with the leader-centered model. As a result of the interaction between top leadership and lower levels of employees, employees can feel more like a part of the process instead of merely following orders. This approach will ultimately lower resistance and increase a feeling of ownership for those involved with the change process at all levels.

The change-centric leadership approach we advocate is not the same as “situational” leadership—where the focus is more narrowly on the competence and commitment of the followers—but is a more whole systems approach. By “whole systems” we follow Atwood et al.’s (2003) notion of a comprehensive approach that requires leaders to build trust and collaboration among affected interest groups, users, communities, and potential partners and stakeholders. In this approach, the leader is not working in a vacuum for change: “leaders need to develop coherent frameworks within which people can decide what should remain the same and what should change” (p. 61). Numerous stakeholders are involved in the change process, and the leader facilitates the interaction among internal and external stakeholders regarding change initiatives.

Dunphy provides further support for our definition of change-centric leadership. Theories about the source of change leadership are based on the false assumption that “unitary leadership” is present in every organization (Dunphy in Beer and Nohria 2000). Dunphy argues that more than one leadership movement is often present in an organization, which could result in multiple change efforts being promoted at the same time. These movements could also come from various levels in the organization.

According to Dunphy, an organization that is attempting to change needs to have strategic goals from top management as well as tactical involvement by informed and knowledgeable members of the organization at all levels. Change-centric leadership offers a framework for dealing with multiple change initiatives from varying levels within the organization through facilitation and open discussion.

The idea of change-centric leadership is also supported by the existing literature on leading through stewardship. Stewardship involves creating a balance of power in the organization, establishing a primary commitment to the larger community, having each person join in defining purpose, and ensuring a balanced and equitable distribution of rewards. Stewardship is designed to create a strong sense of ownership and responsibility for outcomes at all levels of the organization (Kee 2003).

Steven Kelman, former director of the Office of Federal Procurement Policy within the Office of Management and Budget, presents a prime example of change-centric leadership in his book Unleashing Change. Kelman recounts his firsthand experience leading procurement reform efforts during the first Clinton administration. Although Kelman saw a need for reform, he did not push a change agenda down through the ranks. Instead, he sought information and found that many of the frontline procurement officers were also calling for change in the system. Kelman refers to these individuals as the “change vanguard” (2005).

Kelman used the power of his position to unleash the change effort that was fermenting at the lowest levels. In this instance, he served as a facilitator of the change effort; he was a leader pushing for change while simultaneously helping those in the change vanguard see their initiatives succeed. Procurement reform is widely viewed as one of the success stories of the Clinton administration’s “Reinventing Government” efforts (Kettl 1998).

Potential Weaknesses of Change-Centric Leadership

Although the change-centric framework provides middle ground to the top-down, bottom-up dichotomy, its implementation poses some potential challenges. The first deals with the tough questions of how much facilitation is needed and in what context. It is easy to say that a combination of leadership from the top and involvement from lower level employees is ideal in a change environment, but how much of each should be sought? As with most complex matters, the unsatisfactory answer is: it depends. Many issues, such as available time and resources, the skill level of those implementing the change, past experiences with organizational change, and technology that may aid the change process will influence how much control the change-centric leader should exert in any given change program. The more experience a leader has in overseeing change, the greater the chance that he or she can be a successful change-centric leader, providing the right balance of facilitation and control.

Another potential drawback to change-centric leadership is that those facilitating the change process may focus too much on the process of involving others in the plans rather than on the change itself. The danger is that the change-centric leader could become too process-oriented and lose sight of how to achieve the long-term change objectives. The leader must balance the competing demands of engaging in a collaborative process and guiding those involved toward the end goals—and not get lost in the process of change.

A final challenge of this model is the potential for ambiguous accountability. With so many people at different levels within the organization involved in the change effort, it may be easy for individuals to assume that someone else has responsibility for a task that may fall under their reach. To avoid confusing questions of who is accountable for what, clear tasks and measures need to be identified early in the process so that everyone knows exactly how he or she will contribute as the change progresses.

TRANSFORMATIONAL STEWARDSHIP: ATTRIBUTES OF CHANGE-CENTRIC LEADERS

We believe that for public and nonprofit leaders to be successful, change-centric leaders must become transformational stewards of their organizations (Kee, Newcomer, and Davis 2007). Transformational stewardship, in the broadest sense, can be thought of as a leadership function in which those exercising leadership (those with “legitimate” authority as well as others throughout the organization exercising a leadership role) have developed certain attributes that provide a foundation for their actions. These attributes reflect leaders’ personal outlook or attitude (their inner-personal beliefs or values), how they approach a situation (their operational mindset), and how they involve others in the function (their interpersonal abilities/interactions with others).

The dominant advice in the literature on change management is that public and nonprofit sector leaders (much like their private sector counterparts) must “overcome” resistance to change, through a variety of top-down approaches designed to influence the agency’s stakeholders (see, for example, Kotter 1996). Atwood and colleagues (2003) refer to this—in its extreme version—as “Mad Management Disease,” the notion that if leaders can just impose enough controls, supply the “right vision,” and develop the appropriate “carrots and sticks,” they will successfully overcome the change resisters. However, our research finds that success with public and nonprofit sector changes depends on much more than compliance through rewards and punishments (even though reinforcement is an important aspect of successful change).

We believe that, rather than relying on top-down controls, public and nonprofit sector change leaders must employ a model of change leadership that engages other stakeholders in a “whole systems” approach to the change process. Rather than focusing on which level of the organization should institute the change effort, transformational stewards develop a variety of collaborative processes to find the proper balance of strategic leadership and involvement by informed and knowledgeable members and stakeholders at all levels of the organization.

Table 2.2 provides an overview of the key attributes of transformational stewards. Table 2.3 summarizes the supporting evidence in the research literature for those attributes.

Inner-personal Leadership Beliefs or Values

We believe that the most important personal leadership attributes are not ones we are born with, but those we develop throughout our lives. These attributes provide us continuing guidance on how to act in a particular situation, in essence becoming innerpersonal guides to our actions. The most vital attributes for transformational stewards are ethical conduct; a reflective, continuous learning attitude; empathy toward others; the foresight or vision to lead an organization toward a preferred future; and a propensity toward creative and innovative actions.

TABLE 2.2: Attributes of Transformational Stewards

Attribute |

Description |

INNER-PERSONAL BELIEFS OR VALUES |

|

Ethical |

Maintain high standards of integrity for themselves and their organization, recognizing that change issues may pose ethical dilemmas. |

Reflective/Learning-oriented |

Able to step back from the situation and consider alternatives; learn from success and failures; self-aware; tolerant of other views. |

Empathetic |

Demonstrate concern for those who might be affected by the change initiative, both within and outside the organization. |

Visionary/Foresight |

Able to look beyond the current situation and view the change relative to the big picture for the mission and the organization, creating a vision for the future. |

Creative/Innovative |

Take a pragmatic approach to the organization’s change needs; open to new ideas of what is possible; use intuition and inspiration; willing to take risks; not tied to past dogmas. |

OPERATIONAL MINDSET |

|

Trustee/Caretaker |

Act in trust for others—the public in general and future members of the organization. |

Mission-driven |

Fiercely and courageously pursue the organization’s mission; create a “common purpose” for the change. |

Accountable |

Measure change results in multiple ways, in a transparent fashion, and share with those who contribute to the organization’s success. |

Integrative/Systems Thinker |

Understand forces for change and interrelationships; able to find integrative, rather than polarizing, solutions. |

Attention to Detail |

Able to distinguish between details that impact people and the “red tape” that slows change. |

Comfortable With Ambiguity |

Able to balance conflicting organizational objectives and priorities—continuity and change, efficiency and equity, etc. |

INTERPERSONAL ABILITIES/INTERACTIONS WITH OTHERS |

|

Trust Builder |

Develop community and maintain trust with the members of their agencies, constituents, and principals (legislatures, boards of trustees, political leaders). |

Empowering |

Decentralize authority and real decision-making throughout the organization so others can become co-leaders and stewards of change in fulfillment of the public interest. |

Democratic |

Work with others in an inclusive fashion and involve stakeholders in decisions about what constitutes the public interest. |

Power Sharing |

Rely less on positional authority and more on persuasion, moral leadership, and group power to achieve change goals. |

Coalition Builder |

Recognize the importance of building coalitions with others within government and in the nonprofit and for-profit sectors to facilitate change. |

SOURCE: Adapted from Kee, Newcomer, and Davis (2007).

TABLE 2.3: Attributes of Transformational Stewards—Supporting Authors

Attribute |

Selected Supporting Authors |

INNER-PERSONAL BELIEFS OR VALUES |

|

Ethical |

Burns 1978; Ciulla 2004; Fairholm 2000; Johnson 2005; Thompson 2000. |

Reflective/Learning-oriented |

Greenleaf 1977; Senge 1990; Thompson 2000; Wheatley 2005. |

Empathetic |

Autry 2001; Coles 2000; Goleman 1998; Thompson 2000. |

Visionary/Foresight |

Bass and Avolio 1994; Bennis and Nanus 1985; Burns 1978; Fairholm 1997; Follett in Graham 2003. |

Creative/Innovative |

Bennis 2000; Dunphy 2000; Harmon 2007; Kee and Setzer 2006; McSwite 2001; Thompson 2000; Vaill 1996. |

OPERATIONAL MINDSET |

|

Trustee/Caretaker |

Block 1993; Denhardts 2003; Diver 1982; Kass 1990; Kee 2003. |

Mission-driven |

Block 1993; Kee and Black 1985; Follett in Graham 2003; Matheson and Kee 1986. |

Accountable |

Behn 2001; Block 1993; Demming 1986; Harmon 1990, 1995; Moe 2001; Romzek and Dubnick 1987; Vaill 1989b. |

Integrative/Systems Thinker |

Atwood et al. 2003; Follett in Graham 2003; McSwite 2001; Senge 1990; Thompson 2000; Vaill 1996. |

Attention to Detail |

Addington and Graves 2002; Block 1993; Moe 1994; Terry 1995. |

Comfortable With Ambiguity |

Depree 1989; Harmon 2007; Kee and Black 1985; Thompson 2000; Vaill 1989a. |

INTERPERSONAL ABILITIES/INTERACTIONS WITH OTHERS |

|

Trust Builder |

Fairholm 1994, 2000; Greenleaf 1977; Mitchell and Scott 1987; Phillips and Loy 2003. |

Empowering |

Denhardts 2003; Follett in Graham 2003. |

Democratic |

Autry and Mitchell 1998; Follett in Graham 2003; Hill 1994; Kee 2003. |

Power Sharing |

Behn 2001; Harmon 2007. |

Coalition Builder |

Kelman 2005; Phillips and Loy 2003. |

SOURCE: Adapted from Kee, Newcomer, and Davis (2007).

Ethical

An overriding inner-personal attribute is integrity or ethical values and standards. Transformational stewards must maintain a high level of standards for themselves and their organizations, which will allow leaders and followers to elevate the organization to a higher plane. Leadership scholar James MacGregor Burns (1978) posits that moral values lie at the heart of transformational leadership and allow the leader to seek “fundamental changes in organizations and society” (Ciulla 2004, x).

Similarly, those arguing for a servant-leadership approach (often aligned with the concept of stewardship) argue for the importance of “core ethical values, including integrity, independence, freedom, justice, family and caring” (Fairholm 1997, 133). Ethics and moral standards have their roots in principles we learn throughout our lives, either from parents and mentors or from our own inquiries into what constitutes just action.

Reflective/Learning-oriented

Wheatley suggests that: “Thinking is the place where intelligent actions begin. We pause long enough to look more carefully at a situation, to see more of its character, to think about why it is happening, and to notice how it is affecting us and others” (2005, 215). Transformational stewards are willing to step back and reflect before taking action. They take the time to understand and to learn before and during the acting.

Thompson argues that “Beyond a certain point, there can probably be no personal growth, no individualization, without the capacity for self-reflection” (2000, 152). While continuous learning is critical for organizations (Senge 1990), it is equally important for individuals. Self-reflection, including personal awareness and continuous learning, is not always easy or calming—just the opposite, “It is a disturber and an awakener” (Greenleaf 1977, 41). Transformational stewards must be awake to new approaches to problems, new understandings of relationships, and potential consequences of actions and impacts on others. Only then they can lead with confidence.

Empathetic

A transformational steward demonstrates concern for others, both within and outside the organization. Organizational change involves potential winners and losers. If leaders are seen as acting primarily in their self-interest, transformation of the organization can be derailed. However, if leaders show a genuine concern for others and address potential losses, they may find the path easier. Empathy is an attribute that is a product of both our nature and how we are nurtured; understanding its importance can provide us with an incentive to pay more attention to the needs, views, and concerns of others.

Empathy is more than just being a “good listener,” although that is an important skill. Leaders must both hear and understand. Thompson explains: “If by that we mean only that we have learned certain skills and techniques that make the other person feel heard, we have still largely missed the point. To empathize is to both hear and understand, and to grasp both the thoughts the other person is trying to convey and the feelings he or she has about them” (2000, 181). Transformational stewards participate in other people’s feelings or ideas, leading to a broader understanding of the situation and potential courses of action.

Visionary/Foresight

A transformational steward is able to look beyond the current situation and see the big picture and the organization’s potential. While this is true throughout the organization, as a leader progresses in an organization and assumes more responsibility, he or she requires greater vision and foresight (Follett in Graham 2003).

Mary Parker Follett refers to the need for leaders to “grasp the total situation…. Out of a welter of facts, experience, desires, aims, the leader must find the unifying thread…the higher up you go the more ability you have to have of this kind. When leadership rises to genius it has the power of transforming, transforming experience into power” (Follett in Graham 2003, 168–169).

While vision is necessary to transform an organization, it is equally necessary for a good steward. Failure to fully assess potential gains and risks for an organization will lead to a waste of resources and an inability to achieve the full potential of the organization. Follett continues:

I have said that the leader must understand the situation, must see it as a whole, must see the inter-relation of all the parts. He must do more than this. He must see the evolving situation, the developing situation. His wisdom, his judgment, is used, not on a situation that is stationary, but on one that is changing all the time. The ablest administrators do not merely draw logical conclusions from the array of facts of the past which their expert assistants bring to them, they have a vision for the future. (169, emphasis added)

Creative/Innovative

Transformational stewards do not wait for a crisis to innovate and create; they attempt to build an environment that values continuous learning and in which workers constantly draw on current and past experiences to frame a new future for the organization. Vaill (1996) acknowledges that “creative learning” is seemingly a contradiction in a world of institutional learning where people who “know” transfer knowledge to people who do not know. However, in a change environment there often is no “body of knowledge” to transfer; thus, it is up to the transformational steward to create or facilitate creation of the knowledge. This requires a pragmatic, inquiring mind that is willing to explore options, open to new ideas, and not bound by rigid dogmas.

Transformational stewards are leaders of action; their processes involve extensive interaction and relationships with others in the organization and with concerned stakeholders outside the organization. They look for linkages and interconnections. Aware that there are limits on what can be known, they are willing to be tentative, to be experimental in deciding and taking action (McSwite 2001; Harmon 2007). Just as an artist might not always know what the final product will look like, transformational stewards must be open to the unknown, willing to surprise themselves, and able to recognize that “in that surprise is the learning” (Vaill 1996, 61).

Operational Mindset

The “style” approach or theory of leadership focuses on how leaders interact with followers and stresses the need for leaders to balance “concern for people” with “concern for production or results.” The Blake and Mouton Managerial Grid is one of the best known tools reflecting this approach (1985). We believe that the operational mindset of a transformational leader includes but goes beyond simply balancing people with results, and includes a number of attributes of both transformational leader and steward.

Trustee/Caretaker

Transformational stewards recognize that they hold their position and use organizational resources for others and the public interest, not for self-aggrandizement. They take responsibility for the public in general, both current and future generations, as well as future members of the organization. Thus, the broad concept of “the public interest,” while not always easy to define, must be a constant touchstone for the leader.

Public and nonprofit servants, whether elected, appointed, or part of the civil service system, are only temporarily in charge of their resources and responsibilities. They hold them in trust for the public—hence they serve the public and must act in the public interest, not for personal self-interest. “Public managers are, after all, public servants,” argues Colin Diver (1982, cited in Moe 1994). “Their acts must derive from the legitimacy, from the consent of the governed, as expressed through the Constitution and laws, not from any personal system of values, no matter how noble” (404).

A public steward must be willing and able “to earn the public trust by being an effective and ethical agent in carrying out the republic’s business” (Kass 1990, 113). Because ethical considerations may conflict with efficiency criteria, Kass believes that stewardship requires that efficiency and effectiveness (the traditional measures of administrative success) be “informed by and subordinated to the ethical norms of justice and beneficence” (114).

Mission-driven

Transformational stewards fiercely and courageously pursue the mission of their organization. In most cases, they act as agents of those who established that mission—the legislature, a board of directors, the chief executive, or the courts. Sometimes, conflicting goals and agendas require public and nonprofit servants to arbitrate.

Behn poses the question “What should public managers do in the face of legislative ambiguity: ask for clarification, or provide it?” He answers it by saying that public managers must courageously define their responsibilities (1998, 215). It may be in the legislature’s interest to be ambiguous; moreover, “the political process itself creates a diffusion of power and responsibility that makes articulation of central values difficult” (Kee and Black 1985, 28). Thus, the transformational steward must seek to find the common purpose, values, and aims that drive the organization.

Public stewards can find this common purpose by engaging people in their agencies, citizens, and other stakeholders who will assist them in defining the organization’s mission or core values—in effect, determining the public interest. Follett notes that the “invisible leader” becomes the “common purpose” and that “loyalty to the invisible leader gives us the strongest possible bond of union” (Follett in Graham 2003, 172).

At other times, the organizational mission is clear, but the organization may have multiple means of achieving the mission; its leaders must weigh how those means will affect the organization, its mission, and the larger public interest. “Legislation, public scrutiny, and constitutional checks and balances all create legitimate legal and political limitations on the freedom of public managers to act. Yet within the constraints, there is considerable room for experimentation and action” (Kee and Black 1985, 31). Unless proscribed or prescribed to act in a certain fashion, the transformational steward (with the people in the organization) has considerable latitude in pursuing the change mission.

Accountable

Transformational stewards measure their performance in a transparent fashion and share those results with the public and those who can affect the organization and its success. This is consistent with efforts at the federal level to get agencies to articulate and measure progress toward their performance goals (e.g., the Government Performance and Results Act) and to enhance public accountability (e.g., the Sarbanes-Oxley Act).

Transformational stewards support processes such as performance-based budgeting, balanced scorecards, and other efforts to measure program results in an open fashion and to subject those results to periodic review and evaluation. Measurement is not important for the sake of measurement or for the creation of short-term output measures, but for the sake of legitimate feedback and program revision aimed at achieving the agency mission. “Stewardship asks us to be deeply accountable for the outcomes of an institution….” (Block 1993, 18).

An open process ensures public accountability and allows others to see how the organization and its stewards are defining and fulfilling the public interest. This, by necessity, must be a multifaceted process, as Vaill (1989a) suggests, that considers a variety of important values, not simply economic ones that might drive a bottom-line mentality. An open process provides a natural check on how transformational stewards define and lead progress toward achievement of the organization’s mission. Finally, transformational stewards, throughout the organization, take responsibility (legal, professional, and personal) for the results (Harmon 1990, 1995).

Integrative/Systems Thinker

Thanks largely to Peter Senge’s groundbreaking book The Fifth Discipline (1990), systems thinking has become one of the most important concepts in the field of leadership. But systems thinking is not always an easy concept to grasp or apply. Vaill (1996) notes that continuing evidence demonstrates an absence of systems thinking: our tendencies to think in black and white; to believe in simple linear cause-effect relationships; to ignore feedback; to discount relationships between a phenomenon and its environment; and to ignore how our own biases frame our perceptions. Vaill sees the core idea of systems thinking in the balancing and interrelating of three levels of phenomena that all move dynamically in time: first, the “whole,” or the phenomenon of interest itself; second, the inner workings of the whole—the combining and interacting of the internal elements that produce the whole; and third, the world outside the whole that places the phenomenon in its context (1996, 108–109). Vaill argues that the key to learning systems thinking is “understanding oneself in interactions with the surrounding world” (1996, 110).

Attention to Detail

Transformational stewards know that details do matter (Addington and Graves 2002). Details are often the way in which government programs ensure important democratic values, such as equitable distribution of public benefits or access to public programs. Process “red tape” is often the means by which we ensure adherence to procedural imperatives; however, it should not be used as a cover or an excuse for lack of performance. Rather, transformational stewards need to distinguish between those processes designed to achieve certain public purposes and those designed primarily to impose excessive control. With the latter, transformational stewards might seek waivers, exceptions, etc., to enable the organization to manage itself better to accomplish its mission.

Comfortable with Ambiguity

Transformational stewards recognize that conflicting organizational objectives and priorities often require a careful balancing act: continuity and change; efficiency and equity; and so on. Public and nonprofit leaders, like their private counterparts, live in an era of “permanent white water,” bombarded by pressures from both within and without the organization (Vaill 1996). Transformational stewards recognize that their “solutions” are among many plausible alternatives and must be pragmatically reassessed and adjusted as conditions change.

Interpersonal Abilities/Interactions with Others

Leadership theories increasingly stress the importance of the leader’s interaction with others. For example, the “situational” approach characterizes the leader’s role along a “supportive” and “directive” matrix, based on the development level of the followers (Hersey and Blanchard 1993). Leaders delegate, support, coach, or direct, depending on the capacity of the followers—specifically with regard to the job (competence) and psychological maturity (commitment) of the followers.

Transformational stewards often approach their interactions with others differently than many leadership theories prescribe. The chief goals for transformational stewards are engaging, empowering, and engendering trust in employees throughout the organization, and building coalitions with other organizations and stakeholders that are important to the success of the change.

Trust Builder

Transformational stewards build program success through developing and maintaining trust—with the members of their organizations, their constituents, and their principals. Leadership is mainly about developing trust, with leaders and organization members accomplishing mutually valued goals using agreed-upon processes. “Leaders build trust or tear it down by the cumulative actions they take and the words they speak—by the culture they create for themselves and their organization members” (Fairholm 2000, 91).

Developing trust is about engaging the organization’s employees, building community—“the creation of harmony from, often diverse, sometimes opposing, organizational, human, system and program functions” (Fairholm 2000, 140). Public stewards also must build trust with the citizens they serve and the principals (executives and legislatures) to whom they report. Nonprofit stewards must build trust with their board of directors, their donors, and the community they serve.

Mitchell and Scott (1987) insist that stewardship “is based on the notion that administrators must display the virtue of trust and honorableness in order to be legitimate leaders” (448). Trust is ephemeral—hard to gain, easy to lose. Trust encourages the involvement of citizens and often leads to grants of discretion from principals.

Empowering

Closely related to trust is the concept of empowerment. Trust demands empowerment of an organization’s employees and, where possible, decentralization of authority—real decision-making—throughout the organization. Follett, writing in the 1920s, put it this way: “Many are coming to think that the job of a man higher up is not to make decisions for his subordinates but to teach them how to handle their problems themselves, teach them how to make their own decisions. The best leader does not persuade men to follow his will. He shows them what is necessary for them to do in order to meet their responsibilities…the best leaders try to train their followers themselves to become leaders” (Follett in Graham 2003, 173).

Developing leaders for a common purpose is a key function of transformational stewardship. Stone (1997) makes a useful distinction between the market and the “polis.” In the market, economic principles and incentives are the norm. In the polis, the “development of shared values and a collective sense of the public interest is the primary aim” (Stone 1997, 34). To the extent that leaders empower others (employees and citizens), they become co-leaders and stewards in fulfillment of the public interest. This is a fundamental role and opportunity for transformational stewards throughout the organization.

Democratic

Becoming co-leaders and stewards in fulfillment of the public interest, as Stone suggests, requires transformational stewards to engage in democratic processes that ensure the widest possible involvement of others in defining the public interest and in acting on that definition. Harmon suggests a “unitary” or “process” conception of democratic governance based on the notion of “collaborative experimentation” (2007, 71). Decisions would use criteria that are local, context-specific, and flexible, rather than relying on inflexible decision rules.

Harmon suggests starting with a generic question, “How shall we live together?” This would be followed by a more context-specific, “What should we do next? (140). As public servants, we promote democratic governance by focusing on what kind of government (or nonprofit organization) can best contribute to the development of its citizens; it is that development that leads to mutual collaboration among citizens, public officials, and public and nonprofit administrators in “both defining and contending sensibly with problems of shared concern” (159).

Power Sharing

Transformational stewards rely less on positional authority for their power and more on personal power sources, persuasion, and moral leadership to effect change (Hill 1994). Beyond personal power, transformational stewards rely on “group power.” Follett claims that “it is possible to develop the conception of power-with, a jointly developed power, a co-active, not a coercive power.” And “the great leader tries…to develop power wherever he can among those who work with him, and then gathers all this power and uses it as the energizing force of a progressing enterprise” (Follett in Graham 2003, 173, emphasis added).

Coalition Builder

Transformational stewards recognize that they cannot fully meet the organization’s mission with their given resources (people, dollars, etc.) without involving others. They know that horizontal relationships and coalition building with other organizations within government, in the nonprofit sector, and in the for-profit sector are essential for their success. Such coalitions might be critical for the organization’s successful transformation or vital when the organization is faced with a crisis (such as Hurricane Katrina). Coast Guard Admiral Joel Whitehead refers to the importance of developing “preneed” relationships, noting that this is one of the Coast Guard’s fundamental principles—a recognition that they cannot do everything and must rely on others as partners in achieving their organizational mission (Whitehead 2005).

EVIDENCE FROM THE CASE STUDIES

Our six case studies, which are described in more detail in Chapter 4, reinforce the importance of the leadership role in organizational change and illustrate many of the attributes that we have identified as important for transformational stewards.

Leadership and Employee Involvement

A major strength of transformational stewardship is that leaders at all levels of the organization are empowered to address the buy-in and resistance problems that are often associated with change initiatives. In the case study of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), leadership was important both at the top and throughout the organization. Dr. Kenneth Kizer was specifically hired as Under Secretary for Health to make changes in a tense environment where the very survival of the veterans’ healthcare system was in question. Kizer is described by others as a strong visionary leader and a committed change agent; his political leadership skills proved critical to gaining the external support needed to move the agency “from a hospital system to a healthcare system.”

Kizer’s VHA strategy was to get everyone to recognize that they were on “a burning platform” that needed immediate and systemic change. Kizer “created a lot of positive energy” and sought to tap into the priorities for change of key VHA staff. One interviewee noted that “you can’t take people somewhere they don’t want to go.” Kizer used a core group of 22 regional leaders to create a change vanguard to guide the plan and achieve ownership of the change at the local level.

While noting that you cannot shift accountability from the head of the organization and that “at the end of the day it is not an absolute democracy,” one interviewee commented that it was important for Kizer and his successors to create a sense of shared leadership, common vocabulary, and collective accountability among all the key stakeholders; they accomplished this through widespread collaboration and sharing of mutual concerns. Performance metrics (developed through collaboration) and performance contracts with VHA managers were used to engender accountability throughout the organization.

Admiral Patrick Stillman, the Program Executive Officer of the Coast Guard’s Deepwater Program, incorporated the “system of systems” vision in the Deepwater mission, emphasizing “interoperability of systems” and “increased operational readiness, enhanced mission performance and a safer working environment.” As Program Executive Officer, Stillman had to translate the broader systems concept into measurable outcomes, while overcoming considerable skepticism among the rank and file regarding the Deepwater approach. One of Stillman’s strengths, according to those interviewed, was his ability to communicate the vision and foster a sense of inclusiveness and joint responsibility.

Admiral Stillman was described as having a strong sense of Coast Guard history and legacy, a sense of Washington, D.C., “beltway” politics, and good speaking skills that enabled him to motivate his staff. One interviewee commented: “He could operate in a political environment without giving in to the pressure; he was open to ideas and teaming with others and had the philosophy that “you get a lot done if you don’t care about who gets the credit.’” Stillman demonstrated a good balance between advocating for the change and allowing ideas to percolate up through the organization.

In the Fairfax County human services delivery case, the vision was set by the County Board of Supervisors. It was left up to the new Department of Systems Management for Human Services (DSMHS) to give substance to that vision.

Fairfax County hired a change-centric leader, Margo Kiely, to initiate the change. Kiely exhibited many of the attributes of transformational stewardship, and her leadership was viewed as critical even by others who had unsuccessfully sought the department directorship. The new director won them over with an open, collaborative leadership style that the change team worked to cultivate throughout the organization. Kiely fostered a culture of learning and sharing, where suggestions from staff were welcomed; many of those suggestions were pursued and decisions not to implement others were explained.

Other methods Kiely used to engage staff included:

• Developing a “learning opportunities program” to provide continuous staff improvement

• Using a “collaborameter” to assess the readiness of groups to collaborate

• Planning through charrettes, which involve the collaboration of all project stakeholders at the beginning of a project to develop a comprehensive plan or design

• Developing a “common vocabulary” for the change effort

• Sharing frequent and descriptive updates and disclosing the reasoning behind high-level decision-making.

Kiely recognized a constant need for the redesign team and top managers to work closely with other leaders and support teams to ensure that information about the change reached everyone. She took a very pragmatic approach to designing solutions and was able to adjust goals as conditions changed (such as the budget shortfall).

Mary Funke’s leadership of N Street Village (NSV) also demonstrated many of the attributes of transformational stewardship. Her strong faith provided an ethical foundation for all her actions. She demonstrated great empathy when making changes to staff or to benefits for NSV’s clients. While the vision of excellence began with her, her involvement of the staff and the board in detailed strategic planning helped everyone assume ownership.

Funke encouraged continuous learning, providing staff training funds even when cutting the total budget. She built coalitions with potential donors and encouraged staff to pay attention to the details of both fundraising and client services. As for personal characteristics of change leadership, Funke cited integrity, high expectations, empathy, a sense of humor, and an optimistic outlook as important.

Generating Support from Key Senior Leaders and Middle Management

Our case studies revealed that one of the major implementation challenges for leaders is communicating with and gaining the support of program leaders within the organization. Sometimes support from senior leadership and middle management is taken for granted; failure to adequately address these important groups can derail a change effort. Middle managers often provide the key link between the leadership vision and the rank-and-file in the organization.

In the case of Fairfax County, the DSMHS director recognized a constant need for the redesign team and top managers to work closely with other leaders and support teams to ensure that information about the change was vetted by everyone. Despite the efforts to incorporate buy-in and collaboration, resistance still existed and had to be managed. One interviewee volunteered that, if she faced the option of undertaking the change process all over again, she would incorporate mid-level managers to act as change champions to help with staff buy-in and thereby facilitate a quicker process of change.

Leadership also is widely fostered throughout the Coast Guard and at the Coast Guard Academy. Several interviewees noted that the majority of Coast Guard leaders come from the small Coast Guard Academy “society,” which creates a great deal of positive collegiality that may, in some ways, make it more difficult to initiate changes. Coast Guard officers, given this bond, constantly ask themselves, “How will this [change] be perceived by my peers?” Such trepidation may have led to more delays than necessary as various factions weighed in during the Deepwater planning process.

While Deepwater has had the backing of the top Coast Guard leadership, some other senior leaders in the Coast Guard remain opposed to the program. Opposition may fade as new assets are delivered, yet one pessimistic interviewee suggested that it might take a new generation to support fully the systems concept embedded in the Deepwater program.

Leadership Development

Continually strengthening organizational leadership is important to enhance the overall change capacity of an organization. In the Fairfax County case, in addition to involvement in the change effort itself, the director of DSMHS developed a variety of training opportunities for her employees. Also, the Fairfax Deputy County Manager had the idea of creating a “university” that would train workers in change- and transformation-related skills. Although this specific idea was not followed through because of budget constraints, it demonstrates the extent to which change-centric leaders think about long-term organizational development.

Transformational stewards look out for the long-term leadership of the organization. N Street Village director Funke is already training a potential successor. In contrast, one of the weaknesses cited in the Hillel transformation was the failure to develop widespread leadership throughout the organization, raising questions about whether the reforms would last after the change in national leadership.

The Coast Guard and other federal military branches include leadership development as part of their employee appraisal and development processes, providing an ongoing source of new leadership. However, strategic and funded leadership development is not widespread in all public agencies and is often lacking in nonprofit organizations. The lack of leadership succession planning constitutes a major challenge as public organizations begin to face a wave of retirements in the coming years (Newcomer et al. 2006).

TRANSFORMATIONAL STEWARDSHIP: A BALANCING ACT

To initiate change successfully, transformational stewards must balance a number of competing interests. In particular, they must work within structural bureaucratic limitations, satisfy (to the extent possible) the diverse, complex interests of stakeholders, and maintain appropriate political and board accountability. At they same time they must consistently move forward with a practical change agenda that enhances agency effectiveness. Leadership development approaches have traditionally sought to address the need for this balance by providing general collaboration, negotiation, and ethics training. We feel that a more complete understanding of the requirements and mechanics of change illuminates the need for a much richer array of skills and experiences.

Is a transformational stewardship approach the “best” approach to change? Because the extent and nature of change risks vary, leaders need to rely on those sources of power and influence that are best able to balance corresponding risks and opportunities. While in some cases the nature of the risk might suggest a leader-centered or follower-centered approach, in most cases, leaders will need to adjust their leadership approach to the nature of the risk—maintaining a balanced approach. Ultimately, this will likely entail transformational stewardship that encompasses both leader- and follower-centered approaches and relies primarily on building community and mutual trust with the various stakeholders in the change effort. Kelman’s experience with procurement reform in the federal government (2005) and our cases involving Fairfax County, VHA, and N Street Village demonstrate that this approach to leadership can work.

Public and nonprofit sector change initiatives involve multiple stakeholders and often high degrees of complexity. Thus, we believe that a transformational steward will best be able to mitigate the unique combination of the sociopolitical environment, stakeholders, resources, and types of risks that arise during public and nonprofit sector change efforts.

SUGGESTED READINGS ON TRANSFORMATIONAL STEWARDSHIP

Burns won the Pulitzer Prize for Leadership (New York: Harper and Row, 1978), and this book represents his latest thinking on the subject of transformational leadership. He focuses on how leaders can evolve from being “transactional” deal makers to dynamic agents of major social change who can energize and empower their followers. Burns provides an historical view of the evolution of American thinking on leadership. He includes such important topics as followers as leaders, moving from engagement to empowerment, the use of power, the importance of “transforming values,” and how to put leadership to work on the world’s most difficult problem—global poverty.

Greenleaf has changed leadership thinking from the leader’s actions over others to the notion of service as the hallmark of effective leadership. He argues that leaders must become attentive to the highest priority needs of followers; in doing so, they will make their organization successful. Greenleaf lays out the concept in a convincing, practical style, with case studies from business, education, foundations, and charities. The 25th anniversary edition contains a thoughtful foreword by Stephen Covey. A complementary book that applies the servant-leadership concepts to everyday management situations is James Autry’s The Servant Leader: How to Build a Creative Team, Develop Great Morale, and Improve Bottom-Line Performance (New York: Three River Press, 2001).

Supportive of Greenleaf’s notion of servant leaders, Block’s concept of “stewardship” calls for rethinking the role of the leader from that of “patriarchy” to “partnership,” which involves the redistribution of power, purpose, and wealth within the organization. Block uses business case studies; however, the concepts are equally (perhaps even more) important for public and nonprofit leaders. Block calls for a radical reengineering of work processes that support a decentralized decision-making and production structure.

The author brings together the writings of Mary Parker Follett, an organizational theorist of the early 20th century whose views on leadership, authority, delegation, empowerment, and constructive conflict have served as the foundation for many of today’s leadership scholars. Follett’s concepts (such as “power with” instead of “power over” and “integration”) continue to provide fresh insights for addressing today’s leadership dilemmas.