CHAPTER THREE

A Model for Leading Change Initiatives

Transformational stewards are leaders in the public and nonprofit sectors. They have the attributes necessary to implement significant transformations in the increasingly complex networks that deliver public services. Having the right traits and skills, however, is not enough.

Our literature review and case studies demonstrate that change leadership also requires that a variety of leadership functions be undertaken within the organization. Some of these actions will be undertaken by the “leader” at the top; some must be initiated by leaders throughout the organization. The key is that change leadership is exercised throughout the organization.

In this chapter we identify key change leadership responsibilities and present a model to assist leaders in diagnosing and implementing change initiatives in the public interest.

CHANGE LEADERSHIP RESPONSIBILITIES

The lifecycle of instituting change in the public sector begins when a legal mandate or drastic change in the immediate environment occurs, or when organizational leaders choose to undertake major changes. Whether a change is imposed or is undertaken from within, the lifecycle evolves from an initial assessment to a reinforcement of the change initiative.

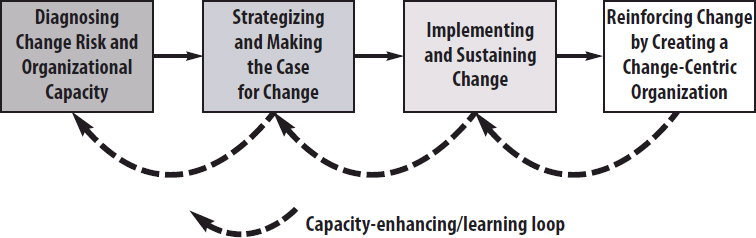

The four critical leadership functions or responsibilities we have identified in this lifecycle are (1) diagnosing change risk and organizational capacity; (2) strategizing and making the case for change; (3) implementing and sustaining change; and (4) reinforcing change by creating a change-centric, learning organization. Effective change leaders must have the capability to make a compelling case for the change being undertaken, and to manage change risk in a manner that protects the agency and the agency’s many stakeholders. Figure 3.1 provides an overview of leadership responsibilities for change in the public and nonprofit sectors.

The leadership responsibilities for change do not usually occur in chronological order; in reality, the responsibilities are not linear but interactive as leadership effectiveness in one area affects the others. For example, effective diagnoses of the change risk and organizational capacity will assist the leader in strategizing and making the case for change; creating a more change-centric organization strengthens the leader’s abilities in the other three areas.

Diagnosing Change Risk and Organizational Capacity

The leadership is primarily responsible for assessing the risks of change and the organization’s capacity for change prior to initiating a change, even if that change is imposed from outside the organization. Key activities in this area include the following:

FIGURE 3.1: Leadership Responsibilities in Public and Nonprofit Sector Change

• Determining change drivers—what is mandating the change

• Analyzing change complexity, stakeholder perceptions, the sociopolitical environment, and organizational capacity

• Facilitating identification/realization of common interests and objectives

• Setting and managing specific change objectives and measures

• Anticipating the overall scope required for integrated total systems change

• Accomplishing change within the capacity limitations of the organization and with a maximum return on resources

• Developing change implementation mechanisms and risk mitigation plans

• Identifying and initiating discussions with potential partners in the change to enhance organizational capacity.

Strategizing and Making the Case for Change

Change initiatives begin with someone, usually a leader—whether at the top or within the organization—articulating a need for change. Effective leaders must constantly scan their external sociopolitical environment and internal organizations for potential drivers of change. Once the need for change is clear to the leaders, they must provide a compelling case for that change to their organizations.

Effective leaders are more than just “goal directed”; they are “vision directed.” Change leaders must have a vision for change that “grabs” the attention of both the internal and external stakeholders of the organization. This cannot be a dreamlike fantasy, but must reflect a possible, achievable action in the “harsh reality” of the current situation (Bennis and Goldsmith 2003).

The central theme of most change management literature is the need for stakeholder buy-in. This is especially important with those stakeholders who have the ability to influence others and garner additional support for the change. The following are important actions to take when making the case for change to stakeholders:

• Establish a sense of urgency for the change through environmental scanning and conveying to stakeholders both evidence to support the reason the change is necessary and the possible risks associated with not implementing the change (Kotter 1996).

• Establish a vision for the change effort that can be communicated to stakeholders and executed. This should be followed by communication of the vision to all stakeholders, along with processes for them to express their feelings and concerns and ask questions for clarification.

• Establish a coalition of stakeholders (i.e., a change vanguard) who support the vision for change and will inspire and encourage other members of the organization to get on board with the effort and “act on the vision.”

Because organizational transformation is most successful with the support of those inside the organization, a sense of urgency accompanied by explicit understanding of why the change is imperative will motivate individuals to get on board and support the effort.

Implementing and Sustaining Change

The leadership tasks do not end with creating a clear vision, strategy, and case for change. Implementing and sustaining change require a constant effort, including the following:

• Establishing transparency, engagement, and collective ownership

• Developing communication and collaboration strategies with stakeholders

• Developing a common vocabulary for all those involved in the change

• Appreciating, understanding, and addressing resistance

• Aligning organizational capabilities (e.g., personnel, processes, structures) with the change

• Developing a system that measures performance of the change

• Celebrating the successes of the change initiative

• Partnering to implement transformation successfully.

These activities must be planned for during the diagnosis and strategy phases and followed through during the implementation and sustaining phases.

Reinforcing Change by Creating a Change-Centric, Learning Organization

Change leaders must constantly reinforce an organizational climate that is conducive to change. To facilitate resilience and productivity in their organizations, leaders have an ongoing responsibility for strengthening their own skills and the vitality of their organizations—to make their organizations more change-centric for the future. This need for constant renewal involves the following:

• Facilitating organizational learning, improvement, and innovation

• Establishing an environment of collaboration, information sharing, and stewardship

• Establishing change implementation management practices, structures, and strategies

• Creating a variety of feedback procedures to foster a learning environment

• Developing transformational stewards throughout the organization

• Developing a transformational ethic as part of the organization’s culture.

A MODEL FOR LEADING CHANGE IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST

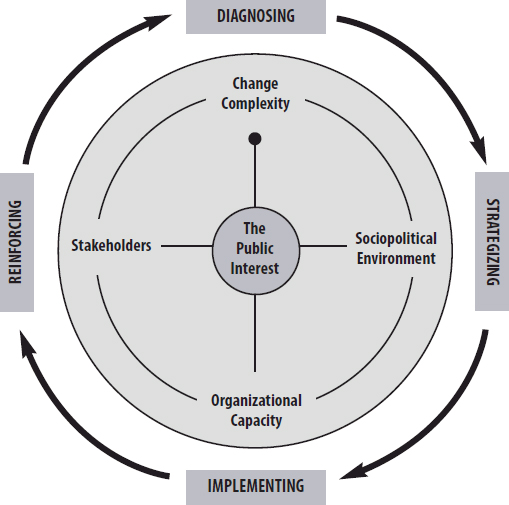

Each of the four stages of leadership responsibilities is important. Effective change leaders need to analyze and address the factors affecting the change initiative throughout the change cycle. We present a “Leading Change in the Public Interest” model to assist change leaders in diagnosing, implementing, sustaining, and reinforcing change initiatives (see Figure 3.2). The model comprises the four processes or phases (diagnosing, strategizing, implementing, and reinforcing) as well as four factors that we believe change leaders should continually monitor as they proceed:

• Change complexity: the magnitude, scope, and fluidity of the initiative

• Stakeholders: those individuals and organizations that perceive they have a role in, or are affected by, an organizational change, including both internal and external stakeholders

• Sociopolitical environment: the context in which the change takes place.

• Organizational capacity: the organization’s ability to initiate and sustain a major change effort, which involves leadership throughout the organization, the organizational culture, change implementation mechanisms, and performance measurement.

At the heart of all efforts must be a continuing focus on the public interest.

FIGURE 3.2: A Model for Leading Change in the Public Interest

Change Complexity

We believe that change complexity should be the initial focus for evaluating the risk associated with a change effort. Change complexity must be assessed and anticipated both in advance of a major change and during the change process itself. A change that is too complex, is opposed by many stakeholders, and is undertaken where the organization lacks strong capacity will likely fail.

Change leaders and managers should assess numerous aspects of complexity, both to assess how pertinent or significant they are to the change effort and to determine how well prepared the organization is to address the implications of the complexity level. Assessing complexity in advance of initiating a change increases the likelihood of a positive result, although in an unpredictable, turbulent environment additional challenges to implementation also may emerge.

While there may be many ways to analyze the complexity of a change initiative, we believe that complexity can be assessed effectively by focusing on the magnitude, scope, and fluidity of a change effort. In other words, how big an impact does the change have on the organization as a whole, how deeply does the change affect the organization, and is the change initiative itself likely to be amendable in response to unexpected changes in the sociopolitical environment? We have created a checklist of questions to guide leaders and managers in assessing the complexity of a change effort, focusing on the magnitude, scope, and fluidity of the change (see Table 3.1).

If leaders of the organization systematically assess complexity by answering these questions, they will enhance their ability to anticipate and cope with obstacles. Failure to comprehend the nature of a change initiative up front can lead to problems during the implementation phase of the change initiative.

How should leaders strategize when the responses to the questions reveal a highly complex change initiative? In the short run, leaders can reduce the complexity of a change initiative by reducing the magnitude or scope by scaling down the change effort, starting with a pilot project or phased approach to the change, or engaging a partner (with more capabilities) in the change effort. Building a more change-centric and capable organization can strengthen the organization’s ability to implement more complex changes over the long term.

Magnitude

We define magnitude as the overall size, extent, and coverage of a change in relation to the organization. Magnitude generally refers to the number of people or stakeholders potentially affected by the change effort, both within and outside the organization. Magnitude also refers to how many locations or divisions within the organization stand to be affected by the proposed change: The more locations and divisions affected, the more complex the change. In addition, magnitude captures the number of people who must be brought on board to support the change and the need to develop partnerships with other organizations to facilitate the change.

When analyzing the magnitude of a change, it is critical to understand that the importance of the number of stakeholders affected by the change is directly related to how the internal and external stakeholders perceive that the change will alter their daily functioning and their overall satisfaction with the organization. It is also important to gauge how employees view their roles or positions within the organization relative to the change—are they likely to be enhanced or threatened?—because this will have a significant impact on their contributions to the change process.

If stakeholders perceive their own participation in the change effort as a threat to their work, they are less likely to support the overall effort. In some cases, stakeholders who feel particularly threatened may attempt to sabotage the process entirely. On the other hand, stakeholders who perceive that their positions will be enhanced by the change may prove to be valuable allies during the change process.

To gauge the magnitude of a change fully, it also is necessary to assess how the change will affect external stakeholders of the organization. The greater the number of external stakeholders affected, the more complex the change. The first task is to understand and identify the number of external stakeholders likely to be affected and their potential impact on the change effort. In most cases, it is vital to have the buy-in of key outside actors, especially those who have the ability to influence others, either in support of or in opposition to the change. In some cases, it may be necessary to partner with outside organizations to implement the change, adding further complexity to the change initiative.

Scope

The scope of a change initiative refers to the potential impact of the change on the organization’s current culture, structures, policies, strategies, processes, and behaviors. This aspect of the complexity of a change reflects how deeply the change is going to affect the organization’s most essential operational elements. For example, the change may require the use of new technology, different skills, or modified responsibilities. The more systems and structures that need to be modified, the greater the scope of the change and the greater the potential for resistance to the change.

Fluidity

Fluidity, or the adaptability of the change initiative to the shifting nature of the environment, is the third key aspect of the complexity of a proposed change effort. The organization’s ability to adapt and alter processes may depend upon the degree to which the environment is changing during the transformation, thus affecting how the change initiative itself evolves. Change initiatives within organizations are likely to evolve in response to both external and internal factors.

Throughout the planning and implementation process, the change agents may need to shift their focus and revise the planned strategy or tactics. When new external or internal impediments arise, momentum in achieving progress toward implementing changes in processes or systems may suffer. The consequence of not adequately assessing the internal and external environments that will interact with a change initiative is that the leaders of the change may not be ready to adapt and refocus their efforts.

Stakeholders

Stakeholders are the individuals and organizations that perceive that they have a role in, or are affected by, an organizational change. Internal stakeholders are the employees located within an organization undergoing change. External stakeholders are located outside the organization undergoing transformation, usually including Congress, the executive branch, private interest groups, other governmental or nonprofit organizations, and citizens. Private contractors to public and nonprofit sector organizations are also considered external stakeholders.

The key elements to be assessed regarding stakeholders are (1) the degree of diversity among the stakeholders, in terms of profession, worldview, and mission orientation; (2) the perceptions of stakeholders regarding their potential gain or loss from the change initiative; and (3) the existence (or lack) of collaborative networks among stakeholders to facilitate communication among them and between leaders and important stakeholder groups.

Diversity of stakeholders, based on group values, professional training, and commitment, can increase the challenges to leading change. For example, management of homeland security and public emergency issues requires collaboration among stakeholders from many different professions (Klein 1999). Direct contact and communication with all stakeholders involved in a change process are key to ensuring successful change efforts. When collaborative networks are available to facilitate communication during change initiatives, planning and implementation become much easier.

To assist change leaders and managers, we have developed a set of questions that will help gauge the role of stakeholders in change initiatives. If organizational leaders can confidently answer the questions in Table 3.2, they have a good understanding of the perceptions, diversity, and collaboration processes involving stakeholders. In addition, they will be able to diagnose potential problems and to take actions to ensure stakeholder buy-in and support during implementation. If leaders do not know the answers or find that the extent of their knowledge and preparation is minimal, stakeholders may not be managed effectively as change is implemented, heightening the risk of implementation weaknesses or failure. (Chapter 5 provides change leaders with approaches to strengthening communication and collaboration with stakeholders.)

Sociopolitical Environment

The sociopolitical environment is the context in which the change takes place. This includes legal and policy mandates and constraints, economic and fiscal conditions, and the levels of support and trust the agencies receive from key political actors and the general public.

External demands on public organizations include legal and regulatory constraints and initiatives, catastrophic events (such as 9/11) that expand agency requirements, and political and citizen support that may influence what is possible. Critical external actors can be supportive, express opposition, or remain neutral regarding an organization and its change initiative. A public organization’s credibility or image, its legal flexibility, and its budgetary resources are a function of both the external environment and the internal capabilities of leadership.

Change leaders must assess the environment to identify potential opportunities and problem areas, as well as their organization’s capacity to respond to environmental factors. In assessing organizational capacity, leaders must first determine whether the organization has an ongoing process for monitoring the external environment to identify potential problem areas and opportunities that may affect the change initiative. Second, leaders must determine whether the organization has developed structures and processes that can influence the external environment (to the extent possible) to support the change initiative.

Two approaches to addressing the sociopolitical environment are environmental scanning and SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis. Environmental scanning is “the internal communication of external information about issues that may potentially influence an organization’s decision-making process. Environmental scanning focuses on the identification of emerging issues, situations, and potential pitfalls that may affect an organization’s future” (Albright 2004). Information gathered through environmental scanning is provided to key leaders and managers within the organization and is used to guide future plans and change efforts.

SWOT analysis generally involves a group planning exercise that may include both internal and external stakeholders, to ensure that all views are available to the organization. Both SWOT analysis and environmental scanning are used to evaluate an organization’s strengths and weaknesses in response to external opportunities and threats. Successful change organizations are adept at both analyzing and reacting to their sociopolitical environments.

Based on our research, we have developed a list of issues that change leaders should consider when assessing the impact of the external environment on a change effort and the capacity of the organization to address the changing environment. These issues are listed in Table 3.3.

Change leaders and agents who continually and effectively monitor their external environment and understand how that environment affects their organization are more likely to find methods to mitigate obstacles or constraints imposed from outside as they plan and implement change initiatives.

Organizational Capacity1

An organization’s internal capacity or capability to initiate and sustain a major change effort involves a number of aspects and is affected by both human and material resources.

Kaplan and Norton (2005), for example, argue for the importance of “organizational capital,” consisting of leadership, culture, alignment, and teamwork in change efforts. McKinsey’s Capacity Assessment Grid for nonprofit organizations includes aspiration (vision and mission), strategy, organizational skills, human resources, systems and infrastructure, organizational structure, and culture (McKinsey 2007).

In our analysis of organizational capacity, we have identified and defined the following key elements as necessary to facilitate major change and transformation:

1. Organizational leadership, both at the top and throughout the organization (discussed in Chapter 2, Transformational Stewardship in the Public Interest)

2. An organizational culture that values and supports change initiatives, reinforcing change-centric behavior (discussed in Chapter 6, Creating a Change-Centric Culture)

3. Change implementation mechanisms—strategies, policies, procedures, structures, and systems that support and are aligned with a change initiative (discussed in Chapter 7, Building Change Implementation Mechanisms)

4. Performance measurement—the use of performance data to inform key stakeholders about why and where change is needed, to focus on aspects of programmatic performance likely to be affected by the change, and to reinforce and reward desired outcomes of change efforts (discussed in Chapter 8, Measuring Change Performance).

Within each of these areas, our model suggests that change leaders should go through the four-step process of diagnosis, strategy, implementation, and reinforcement to (1) better understand and mitigate the risks of the proposed change and (2) develop approaches to enhance the long-term change capacity of the organization.

Organizational Leadership

Effective leadership throughout the organization is essential to successful change initiatives. Transformational stewards, or change-centric leaders, create a strong sense of ownership and responsibility for change outcomes at all levels of the organization. Organizational leadership is critical in the processes of making the case for change, assessing risk and initiating change, implementing and sustaining change, and continuing to encourage employees throughout the organization to become change-centric. Each of these areas is important and should be considered when analyzing the leadership aspect of organizational capacity.

One of the major implementation challenges for leaders is communicating with and gaining the support of program leaders within the organization. Sometimes support from senior leadership and middle management is taken for granted; failure to adequately address this important group can derail a change effort. Middle managers often provide the key link between the leadership vision and the actions of the rank-and-file in the organization.

Continually strengthening organizational leadership is important to enhance an organization’s overall change capacity. However, strategic leadership development is not widespread in all public agencies, and the lack of funding and a plan to continually renew organizational leadership constitutes a major challenge, especially as public organizations face the expected retirement of senior leaders in the coming years (Newcomer et al. 2006).

One of the most important tasks for leaders of change is to examine whether their organization has the requisite change leadership. The questions in Table 3.4 may assist in assessing organizational leadership in the context of implementing change initiatives. (Chapter 10 provides leaders and human resource managers with approaches to strengthen change leadership development within the organization.)

If organizational leaders can answer most of these questions affirmatively—that the agency promotes widespread leadership to a great extent—it is likely that the organization’s leadership capacity is sufficient to support change. Any negative answers are potential sources of concern and a call for improvement. Leadership that is lacking in sound change management skills and strategies may find it very difficult to initiate a successful change.

Organizational Culture

Organizational culture is the behavioral, emotional, and psychological state of affairs in an organization, widely accepted “as the way we do things” by all employees. Cultures that are more status quo-oriented and resistant to change may present a significant challenge in leading change efforts. Cultures that are more open and adaptive are likely to be more receptive to change initiatives.

Leaders who initiate major change initiatives must examine their organizational culture and assess whether it is likely to support the change. If the culture is resistant to change, leadership has a twofold challenge. In the short run, leaders have to address potential obstacles to change. In the long run, leaders need to devise strategies to make their culture more change-centric. Table 3.5 presents a set of questions for leaders to address when analyzing their culture. (Chapter 6 provides an approach to developing a change-centric culture.)

The more affirmative the responses to these questions, the higher the likelihood that the culture will provide a strong foundation for change efforts. If many responses are negative, leaders should pursue efforts to make the culture more change-centric during the change initiatives. At the very least, change leaders will need to address those elements of the culture that are most problematic for the change effort. Since cultural change typically comes very slowly, leaders of change will need to address those areas of greatest weakness and develop a broad strategy to gradually introduce the organization to an approach that is more welcoming of change.

Change Implementation Mechanisms

Change leaders need tools to plan, steer, implement, and evaluate organizational changes. While a number of change mechanisms may be helpful, three primary mechanisms are especially effective: (1) the use of strategic management processes to create a shared change vision and to align resources with that vision among employees; (2) the development or more effective use of specific channels (or change structures) to facilitate two-way communications about the change throughout the organization; and (3) the development of continuous improvement programs, after-action reports, and other approaches to creating a learning organization.

As leaders initiate major change, they must take a hard look at their existing strategies, processes, policies, and structures to determine whether they support the change initiative. If agencies have continuous improvement programs or other change mechanisms in place, new changes will occur much more easily. If not, the challenge is twofold. In the short run, leaders have to create a mechanism to initiate the change successfully. In the long run, leaders need to devise a strategy to make processes and structures more change-centric and to encourage their agencies to become “learning organizations.”

Table 3.6 provides a set of questions that can assist leaders in assessing their change implementation mechanisms. (Chapter 7 provides advice on how to create mechanisms that support change initiatives and promote continuous learning.)

The higher the level of positive responses to the diagnostic questions, the greater the likelihood that the organization has implementation mechanisms in place that will be helpful in facilitating change efforts. If the answers to the questions reveal that processes and change mechanisms are lacking, the change risk increases and leaders must focus on building mechanisms to support the change process.

Performance Measurement

Building internal organizational capacity in performance management involves the use of a set of balanced performance measures to focus and inform management about change efforts. To assess change-related performance, performance metrics or measures should capture the implementation and intended outcomes of the change initiative. The extent to which performance measurement is institutionalized in an organization prior to a change initiative is a critical factor: The more accustomed managers are to measuring performance, the easier it will be to use existing processes to support change efforts.

To assess the extent to which performance measurement within an organization is likely to support change efforts, leaders and managers should address the set of questions provided in Table 3.7. (Chapter 8 presents an approach to building an effective performance measurement system for change efforts.)

The higher the level of positive response to these questions, the greater the degree to which performance measurement permeates an organization’s culture. Preexisting processes supporting performance measurement can make implementation of change initiatives easier. The strategic use of a viable performance measurement system provides vital support in leading change.

RELATIONSHIPS AMONG RISK FACTORS

Ultimately, change risk is a function of each of the elements in the model both individually and in terms of how they interact with one another. Thus, the complexity of the change initiative has both direct and indirect effects on risk. The magnitude, scope, and fluidity of a change are variables that are individually important and that also interact with the organization’s capacity to deal with the risks of change and the stakeholders’ perceptions. If an organization’s leaders are comfortable in complex, volatile situations, they may accommodate a complex change more easily. The extent to which stakeholders perceive the change as a threat may exacerbate the risk, or collaboration among stakeholders may reduce risk.

Organizational capacity, stakeholders, and the sociopolitical environment are also linked. Good organizational capacity and effective communication and collaboration approaches to stakeholders can reduce stakeholder perceptions of loss and enhance perceptions of gain. Leadership efforts to monitor the sociopolitical environment can lead to strategies to mitigate adverse events and to gain the support of key stakeholders.

In general, the larger the magnitude, the wider or deeper the scope, and the more fluid the environment of an organization undergoing a change, the more complex the change and the higher the risk of failure. However, the more capable or change-centric the organization, the lower the risk associated with major change and transformation efforts; strong organizational capacity can mitigate change risk.

Table 3.8 provides a summary of the major elements and risk factors involved in public sector change.

TABLE 3.8: Risk Factors in Public and Nonprofit Sector Change

Factors |

Description |

Change Risk |

COMPLEXITY |

|

|

• Magnitude |

Overall size, extent, and influence of the change in relation to the organization |

The greater the number of people and organizational entities affected, the greater the risk. |

• Scope |

Impact on the organization’s current culture, structures, policies, strategies, and processes |

The deeper the impact on organizational culture, structures, policies, strategies, and processes, the greater the risk. |

• Fluidity |

Adaptability of the change initiative to the changing nature of the environment |

The less adaptable the change initiative is to the environment, the greater the risk. |

STAKEHOLDERS |

|

|

• Diversity |

Range of conceptualizations of organizational mission, orientation, and worldview as a function of the size and variety of organizational units and purposes |

The more diverse the organizational viewpoints and perspectives, the greater the risk. |

• Perceptions |

Perceptions of gain and loss held by internal and external stakeholders and the intensity of those perceptions |

The more intensely stakeholders perceive their potential loss, the greater the risk. |

• Collaborative Networks |

Extent to which collaborative processes and structures are in place among internal and external stakeholders |

The more effective the collaboration among stakeholders, the lower the change risk. A lack of collaborative processes increases risk. Effective communication processes among diverse stakeholders reduce risk. |

SOCIOPOLITICAL ENVIRONMENT |

|

|

• Legal and Policy Mandates |

Laws and regulations imposing changes or constraining changes in operations |

The more rigid the regulatory constraints, the greater the risk. |

• Economic Trends |

Resources to support change initiatives from budgets or taxes |

The more vulnerable the funding, the greater the risk. |

• General Political Support |

Citizen trust or demands for or against change |

The greater the public interest in the change, the greater (or lower) the risk. |

• Interface with External Environment |

Capacity of leaders and staff to integrate and accommodate external demands and forces constraining or supporting their actions |

The lower the capacity of leaders and staff to deal with environmental pressures, the greater the risk. |

|

|

|

• Leadership |

Leadership throughout the organization relative to the change |

The more change-centric leadership throughout the organization, the lower the risk. Ineffective leadership increases risk. |

• Culture |

Norms and routines exhibited by people who work in the organization, which signal to employees what they should do, how they should feel, and what they should think about change |

The more supportive the organization’s culture is of innovation and change, the lower the risk. The more resistant the culture is to change, the greater the risk. |

• Change Mechanisms |

Strategies, processes, policies, and structures to initiate, accommodate, and support the change |

The use of strategic management and explicit change structures to facilitate change reduces risk. The lack of such structures increases risk. |

• Performance Measurement |

Strategic use of performance measurement to facilitate change |

The more widespread the use of performance metrics, the lower the risk. Lack of a performance measurement system increases risk. |

IMPLICATIONS FOR CHANGE LEADERS

We conclude this chapter with the inevitable cautionary note about models: They are necessarily simple, attempting to show high-level patterns and relationships to increase their usefulness, at the expense of precision and detail. Every change initiative is different and so is every organization. In the remainder of this book, we analyze how six organizations handled their change initiatives, discuss how our model highlights change-related risk, and offer practical steps that leaders can take when initiating change.

Uncertainties, ambiguities, and anxieties among the parties affected are always associated with change. The diagnostic instrument we provide in Appendix A is intended to assist in analyzing factors that increase the risk involved in change initiatives. Our model is designed to make it easier to envision the dynamics among change complexity, organizational capacity, stakeholders, and the sociopolitical environment. Most of these factors can be controlled at least to some degree, even when change is imposed from outside an organization. While the external environment and the complexity of the change initiative are the factors that are least controllable, continuous collaboration and communication with external stakeholders and enhanced organizational capacity can help increase the probability of successful outcomes.

As we illustrate in the discussion of the cases, the success of change initiatives depends on the degree to which leaders assess, monitor, and recalibrate organizational strategies, processes, implementation mechanisms, and structures to facilitate change. Consistent, proactive top-down and bottom-up transformational stewardship greatly enhances the potential for successful outcomes of change initiatives.

GENERAL READINGS ON CHANGE IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST SUGGESTED READINGS ON LEADERSHIP

The Denhardts present a compelling argument that “new public management” is not the answer for the changes required in public administration. Rather, they call for a reaffirmation of democratic values, citizenship, and service in the public interest. The book is organized around seven core principles: serve citizens, not customers; seek the public interest; value citizenship and public service above entrepreneurship; think strategically and democratically; recognize that accountability isn’t simple; serve, rather than steer; and value people, not just productivity. While not specifically about leading change, this book provides a strong foundation for important public values that are applicable to both the public and nonprofit sectors.

SUGGESTED READINGS ON LEADERSHIP

Kouzes and Posner’s popular book on leadership continues to have a wide following, and the authors have written related books, workbooks, and leadership assessment instruments based on their findings. They present five practices of exemplary leadership: modeling the way (finding your voice and vision); inspiring a shared vision; challenging the status quo (experimenting and taking risks); enabling others to act (collaborating and empowering); and encouraging the heart (providing recognition and creating a spirit of community). With numerous illustrations from leaders the authors interviewed, the book provides a strong foundation for any type of leadership, including change leadership.

In this widely used leadership text, Johnson emphasizes the ethical responsibilities of leaders to provide “light” for their organizations, contrasted with potential “shadows” of power, privilege, deceit, inconsistency, broken loyalties, and irresponsibility. While providing a strong academic and normative foundation, Johnson uses mini-case studies and examples from contemporary movies to illustrate various leadership and ethical dilemmas.

Van Wart provides a comprehensive discussion of various leadership theories and their application to public service, which would be valuable for both public and nonprofit leaders. The book is somewhat academic but provides many useful tables and checklists for students of leadership.

Yukl’s book is regarded as one of the most comprehensive surveys of major theories and research on leadership and managerial effectiveness in organizations. Yukl balances leadership theory and research with practical applications and offers suggestions for improving skills. He also addresses controversies and differing viewpoints about leadership effectiveness. Other topics include charismatic and transformational leadership, influence processes, leading teams, and leading change.

1 The terms “organizational capacity” and “organizational capability” often are used interchangeably, although sometimes there are nuanced differences. Thus, when considering whether an organization is capable of performing certain tasks, the critical factors are often employee skills, processes, and resources. In contrast, we view organizational capacity in a broader sense to include organizational culture and infrastructure. Capacity also is the term most used when assessing nonprofit organizations, and thus the term organizational capacity seems the more accurate in terms of our discussion.