CHAPTER EIGHT

Measuring Change Performance

One of the strong findings that has emerged from our case studies is the importance of using performance measurement strategically to facilitate change efforts. The use of performance data to inform management is not a new concept. The belief that concrete data on program performance, or performance metrics, should guide managers’ decision-making has framed most discussions of management in public and nonprofit agencies in the United States since the early 1990s. With the increased emphasis on quantitative measurement of outcomes, “program performance” has become a higher priority. Measuring and reporting on program performance focuses the attention of public and nonprofit managers and oversight agents, as well as the general public, on what, where, and how much value programs provide to the public (see, for example, Newcomer 1997; Forsythe 2001; Hatry 1999, 2007; Newcomer et al. 2002; Poister 2003; and Newcomer 2008).

Managing performance in public and nonprofit programs has also received attention in the literature on public management reform across the globe (for example, see Kettl and Jones 2003; Hendricks 2002; and Newcomer 2008). Promoting the use of program data when making changes to improve program design and delivery or to reallocate resources is recognized as an extremely challenging but worthwhile goal (Ingraham, Joyce, and Donahue 2003). Performance management in the context of organizational change initiatives entails the coordination of program and employee performance management methods to minimize change risk and maximize change success.

USING PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT TO FACILITATE CHANGE EFFORTS

The extent to which performance measures can be used to facilitate change efforts will reflect the extent to which performance or measurement has been institutionalized in an organization. The degree to which a performance orientation permeates the management culture is affected by many factors, including the tone set by leadership; the availability of valid, reliable, and credible performance data; and the relative freedom managers have to change things—in another words, authority to use performance data to inform managerial decision-making (Mihm 2002; Wholey 2002).

As Government Accountability Office (GAO) analysts and others have observed, there is great variability in the extent to which performance measures are used to support management decisions across federal agencies (for example, see U.S. GAO 2004a; Hatry 2006; and Newcomer 2006a). Federal agencies have complied with statutory requirements of the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) that they routinely measure progress toward performance goals. However, the extent to which managers use the data to make changes in processes or to reallocate resources varies widely.

Implementing change typically requires changes in both processes and resources; in addition, there must be a baseline of data on performance that are perceived to be valid and reliable and that managers can use to make more informed decisions. Deliberations about performance measures and targets, or the design of new measurement systems, are useful in increasing the frequency and the quality of collaboration among both internal and external stakeholders in change processes.

In organizations where performance measurement systems are already established and resources are already devoted to providing credible performance data in a timely fashion, performance data can be used effectively to support change efforts. Where performance measurement systems are not as institutionalized, efforts to develop useful performance measures can support change efforts in several ways. Performance data can be used to:

• Inform useful deliberations among key stakeholders about why and where change is needed—“to make the case for change”

• Focus on aspects of programmatic performance likely to be affected by change

• Track the effects of changes to reinforce and reward relevant stakeholders for the achievement of desired outcomes of change efforts.

Experience with performance measurement at all levels of government and in the nonprofit sector provides important lessons pertinent to change management. Specifically, for performance measurement efforts to add value in change efforts, change agents need to deliberate carefully about the focus, process, and use of performance measurement.

Focus

Concrete measures of performance can provide needed focus in change efforts. However, measurement of programmatic performance is imperfect and controversial, as it may unintentionally reduce managers’ attention in areas where effort is needed but measurement is not made. For example, in an educational setting, teachers may “teach to the test” to meet measurement goals, diverting attention from other important educational objectives. Ideally, performance measures should be aligned with the missions, goals, and objectives of change projects. A focus on outcomes—the desired changes in behavior or conditions that are expected to result from the change project—is likely to direct stakeholder attention to the achievement of critical benchmarks. Stakeholders involved in change initiatives must believe that the performance measures used are credible, however.

The credibility of performance measures can be bolstered by ensuring that the measures are perceived as meaningful and useful. Table 8.1 provides a set of criteria helpful in assessing measures used in public and nonprofit organizations.

Process

Open collaboration regarding the selection and interpretation of measures is essential in performance measurement processes. All stakeholders who are affected by the use of the measures should have input. Identifying legitimate measures early to facilitate communication among key stakeholders can foster collaboration; conversely, the lack of open, transparent processes can engender extremely contentious relationships.

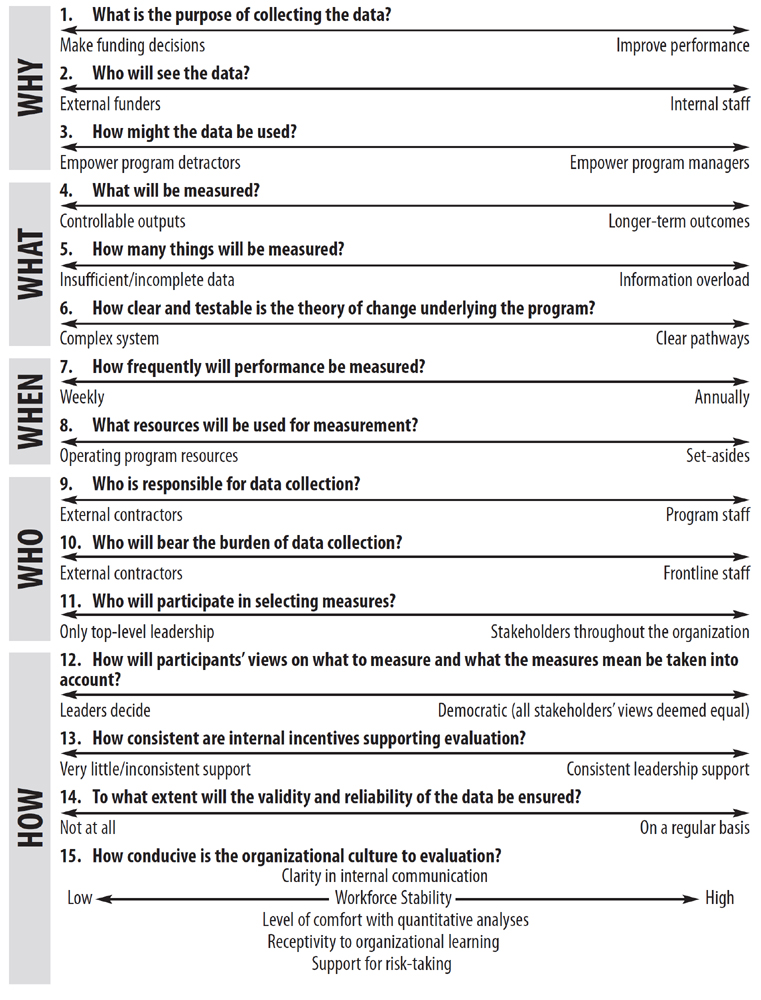

Collecting and reporting performance data may evoke uncertainty for internal stakeholders regarding a number of basic questions, such as:

• Why should we measure performance?

• What should we measure?

• How frequently should we measure?

• Who will collect and analyze the data?

• How should we measure performance?

Table 8.2 presents issues that leaders must address when they design, implement, and use performance measurement systems.

Controversy typically surrounds the use of data documenting programmatic accomplishments. From the perspective of social service providers, for example, when grant requirements specify that grantees must report on who they serve and how much improvement their services made, the message is that accountability is the objective of the measurement. Simply collecting data raises the risk that evidence of “effectiveness” may not surface. Performance data provide the ammunition that can be used by program detractors as well as supporters—and this is not lost on program managers.

TABLE 8.2: Performance Measurement Issues

Even more important is the question: What are the most appropriate measures? In some arenas, quantitative evidence abounds. For example, in health services, data on immunization, morbidity, and mortality rates have been available and used for years. In other service arenas, such as shelters for homeless women and families and community revitalization initiatives, there are not always professionally recognized standard measures. When programs have clearly specified, understood, and validated theories of change, agreement on appropriate measures for outputs and outcomes is more likely than in the case of newer, less tested interventions.

Outputs are more likely to provide workload reporting (e.g., number of clients trained) than to capture the achievement of service goals. It is generally more feasible for providers to tabulate services delivered than to assess results. Workload is controllable; clients typically are not. Tracking the results of services also entails follow-up, which creates more work and requires more resources for providers.

Agencies collecting performance data face the common dilemma of determining how many things to measure. Again, it depends on the type of service provided and how far out on the outcome chain one goes, but there is rarely an obvious, “correct” set of measures. Experience with the U.S. federal and local governments has shown that service providers typically measure too many things, and the information overload can be distracting rather than enlightening.

Who bears the burden of data collection? Both the timing and frequency of data collection activities clearly contribute to the perceptions and real monetary burden imposed by measurement. Following up with clients is time-consuming, as noted. And the degree to which the feasible measurement of outcomes is in sync with reporting requirements can produce more headaches for providers. For example, when grant-reporting requirements specify submission of measures on an annual basis, and program theory indicates a longer trajectory for demonstrating effectiveness, providers face some tough choices.

The manner in which regular performance assessment processes are institutionalized in agencies can also pose dilemmas for program managers. Routine, virtually seamless systems for serving and tracking clients certainly make performance assessment less disruptive for program management. However, the design and maintenance of systems impose requirements and require staff investment of both time and commitment.

In the end, it is leadership support and organizational culture that will significantly affect stakeholders’ receptivity to performance measurement. Consistent leadership support throughout organizations has been repeatedly identified as a critical ingredient for useful and smooth performance measurement (Newcomer et al. 2002; Poister 2003).

Aspects of organizational culture that are correlated with receptivity to organizational learning, such as clarity in communication and support for risk-taking, certainly are likely to increase the ease of measuring performance. Organizations in which the professional backgrounds of the staff make them comfortable with research and quantitative analyses are more receptive to performance assessment. Agencies with lower turnover also are likely to provide more stability for supporting assessment systems. Regardless, however, the tone set by agency leadership and reinforced in the culture will shape the way performance measurement plays out.

Linkages between performance measurement and other management processes, such as strategic planning and budgeting, can help managers see the importance of supporting measurement efforts. Nonetheless, selecting measures that will be used in holding stakeholders accountable for performance requires the candid and prolonged engagement of all affected.

Use

Collaborative development of relevant measures does not ensure that they will be used. Consistent leadership is needed to institutionalize the use of performance measures.

A climate supportive of performance measurement within the network of stakeholders involved in the change effort may be hard to cultivate but can reap benefits. Experience has shown that it is important to emphasize positive, not punitive, uses of the performance data to get buy-in, and to avoid setting targets until the organization has some experience with performance measurement and reporting. Using performance measures to “hold accountable” various stakeholders for change-related outcomes is likely to work only when adequate time is devoted to truly collaborative system-building efforts. Table 8.3 lists some of the many ways that performance measures can be used.

ILLUSTRATIONS FROM THE CASE STUDIES

Our six case studies offer important lessons about how performance measurement can support change management efforts, particularly in terms of focus, process, and use.

Focus

During the implementation phase of Deepwater, the Coast Guard program executive officer (PEO) prioritized development of a robust system of metrics to measure program success. In the VHA case, performance metrics were newly structured to encourage collaboration and innovation. In the Fairfax County case, a highly process-oriented leader and cadre of social workers and administrative professionals designed a use-oriented, numbers-driven performance system.

One of the Coast Guard PEO’s priorities during the implementation phase of Deepwater was to develop a system of metrics to focus efforts and monitor progress. The resulting system for Deepwater, a “balanced-scorecard approach,” was designed by contractor SAS to integrate various databases and focus on “real-time intelligence.” The approach recently won the software industry’s Enterprise Intelligence Award as a “best practice.”

Some interviewees in our study felt that the information Deepwater’s measurement system provides has been underutilized. In response, the current PEO has made better use of the information a priority. He wants to make the data more user-friendly and ensure the proper people are seeing the data they need to make better decisions.

To some, the measures used to monitor contracts with private sector partners (ICGS) were “soft and squishy,” in part because the Coast Guard never developed “good technical performance measures for each asset; [nor was there] baseline documentation on cost estimates.” The newer performance metrics for Deepwater may be useful but were not “written into the contract” with the private partner. The challenge was to get both the contractor and the Coast Guard to agree on the same rules and to use the same information. However, in 2007, the Coast Guard dissolved the partnership and took over the systems integrator function. This was in part because of pressure from Congress, but even more so because of cost overruns and failure of the new assets to meet performance targets. Perhaps this situation could have been avoided if better measures and benchmarks had been in place earlier.

To maintain a “shared environment” and collaboration of efforts, VHA launched a performance metrics program. This program measured six different “domains of value”: quality of care, access to service, satisfaction (initially with patient care and later expanded to include employee satisfaction), cost-effectiveness, restoration of patient functional status, and community health. Each of the 22 directors in the Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) was accountable for his or her specific group’s performance in each domain. This accountability was dispersed throughout the entire organization, from the top directors to the front-line workers. Members of the different VISNs had to work together to maintain success on these performance measures.

As a result of using performance metrics, employee motivation to perform good work improved. Meeting and exceeding the standard measures for performance became the norm. Directors and employees were held accountable for actions and work. Both positive and negative performance were exposed, both within the system and to the numerous stakeholders.

In the Hillel transformation, the new national leader introduced performance measurement and evaluation in the form of accreditation, a system he borrowed from his experience in college administration. The concept of accreditation helped the organization focus on the quality of the programming offered to college students. The entire process included local feedback and was implemented using a bottom-up approach (largely because the local Hillel directors felt the system threatened their job security). A retreat organized by a National Committee on Quality Assurance (composed of a diverse mixture of Hillel’s internal stakeholders) resulted in the Everett Pilot Program for Excellence, which featured a phased accreditation process. Local Hillels engaged in their own self-study in the first stage and then worked with an outside Hillel team who led a site visit and delivered an action plan for the local organization in subsequent phases.

Process

The identification of credible and useful performance measures should be viewed as an inclusive and iterative process. Selection of outcome measures is an especially arduous task when multiple actors are involved in service delivery, as with the multiple agencies involved in social services in Fairfax County, or services are contracted out. Time and patience are needed to ensure that the diverse stakeholders accept and value measurement and reporting.

Performance metrics have been used in a collaborative process to support continuous and successful change in the coordinated service planning organization in Fairfax County. Measures were developed to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of different types of intake and phone processes. Weekly performance metrics reports are shared with the staff so they are aware of how they and the organization are performing, and they are directly, constantly engaged in improving service delivery.

Interviewees reported that it has been much easier to get buy-in from stakeholders when metrics and data substantiate the results and value of organizational change. While social services are sometimes thought to be nonquantifiable and social workers consider their people-focused work to be more qualitatively than quantitatively oriented, the call center staff took great pride in being “data driven” and believed that this approach led to better customer service. Transparency in both the development and sharing of metrics became an important means for reinforcing the change effort. In addition, to link employees across functions, the division employed a “common language” to avoid confusion on terminology.

At N Street Village, the director identified performance management as a core element of her goal to develop a successful “business” model for the nonprofit organization. The director assisted the staff through the learning and change processes. Specific objectives of performance management included updating job descriptions, staff members developing their own performance objectives to serve as the basis for their performance evaluations, and identifying staff training needs.

The NSV director’s strategy involved setting a firm “expectation of excellence,” and while staff members were initially wary of the new approach, they have since succeeded by “raising the bar on themselves.” The director also used the organization’s budget process to reinforce performance goals. For example, in the 2004/5 strategic plan, Objective 4 of Goal 2 (budget), states: “On a monthly basis, each unit manager will work with the Volunteer Coordinator to ensure the use of in-kind donations and volunteers to include a long list of items, including but not limited to: twenty-five percent of all food usage, seventy-five percent breakfast and lunch by volunteers, full evening and overnight coverage of residential programs by volunteers, and all clothing and bedding needs.”

Use

Performance measures may make the implications of change personal, raising the stakes when managers see their own fortunes tied to the change. At VHA, the VISN structure mandated that all the parts of the whole be responsible for and to each other, share in the same risks and rewards, and use their resources in a collaborative effort to reach the same goals. One way VHA practices this type of “shared environment” is by holding medical professionals and administrators directly responsible for patient care. For example, the medical staff monitored how many heart attack patients received recommended beta-blockers and aspirin, and the patients’ outcomes were then linked to the medical staff’s and administrators’ performance reviews.

Using programmatic performance measures to assess individuals or sets of stakeholders in a network requires credible and reliable data. When employee or stakeholder contributions to performance are clear, and performance is regularly assessed and discussed, organizational performance is strengthened. When leaders collaborate vertically with their managers and staff, and leaders and stakeholders work to create a performance-driven culture that is connected horizontally by common performance objectives, it is easier to implement the use of change-related metrics to inform decision-making.

Individual performance appraisals for employees involved in change initiatives and organizational performance management plans should include metrics that reflect the goals and implementation steps of change initiatives. As the vision or objectives in the change process evolve, the performance metrics should be adjusted.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CHANGE LEADERS

Performance measurement processes can be useful in facilitating the implementation of change initiatives. However, determining what to measure, how to measure, and how to interpret and use the measures to inform decision-making all require extensive and candid collaboration among stakeholders. The more diverse the stakeholders are in terms of their organizational values and objectives, the more challenging it will be to secure buy-in for the development and use of performance measures. Securing adequate resources to ensure that measurement systems collect and distribute the data in a timely and user-friendly fashion presents yet another challenge for leaders.

The first responsibility of a change leader is to diagnose the current state of the organization’s performance management system. Is the current system adequate and can it help the organization focus on and track the important areas related to the change? The questions asked as part of our model for leading change in the public interest (in Chapter 3, Table 3.7) provide change leaders with a starting point for that diagnosis.

The second responsibility is to develop a strategy for designing the process to determine the best measures for the change. The involvement of key stakeholders will help ensure buy-in for the measures. Implementation requires the availability of sufficient technical expertise to transform the measurement strategy into data collection.

Finally, performance measurement systems are not effective unless they are used consistently throughout the change process. Change leaders must reinforce the measures through consistent usage and constant discussion of their importance.

The rhetoric about “results-based management” typically outpaces the reality. Effective use of performance measures to guide decisions can become illusory for many reasons. Expectations that all stakeholders will want to systematically track performance in change initiatives, and use the performance data to ensure accountability on an individual, team, or organizational basis, may be unrealistic. Leaders should set politically and financially feasible objectives about the utility of performance measurement in a specific change scenario. Objectives should be tempered by the intra- and interorganizational context in which measures may be helpful.

Illustrations from our case studies, as well as other governmental success stories, suggest that performance measures are extremely helpful in focusing even diverse sets of stakeholders on the achievement of targets. Leaders should be careful not to underestimate the time and effort required to bring everyone on board, however (Hatry 2006; Metzenbaum 2006).

SUGGESTED READINGS ON PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT

The authors review the influence of performance measurement in the federal government. They undertake a clear analysis of five U.S. agencies, including the Food and Drug Administration and the Department of Health and Human Services, to demonstrate how performance measurement works when applied to third-party government.

This book is appropriate for beginners as well as practitioners in performance measurement. Hatry clearly explains performance indicators and benchmarks, and evaluates different uses for performance measurement. He also thoroughly considers new relevant issues, such as the increased availability of technology, as well as issues of quality.

This academic book on performance management design and implementation is an intermediate text on how to create a performance management system. Poister provides both public and nonprofit leaders with tools for devising accurate benchmarks and indicators that can be used to enhance program performance.