CHAPTER TEN

Developing Transformational Stewards

Looking ahead, public and nonprofit service is likely to continue to be characterized by challenges that require leaders to be agents of change in the public interest—what we have been calling transformational stewards. Leaders will be operating in turbulent conditions, including the following:

• Rapid communications that penetrate traditional barriers to information-sharing

• Increasing transparency and public scrutiny regarding ethics, results, and opportunities for improvement

• Evolving information technology, which will break down organizational silos and connect and integrate organizational functions in ways not previously possible

• Changing strategic influences and mission requirements, exacerbated by the nature of cross-jurisdiction, cross-sector, and cross-function interdependencies

• Expectations for more agile and performance-oriented work and organizations

• Increasing top-down guidance and coordination of operational standards and improvement priorities, with some trends toward decentralized operations

• A workforce characterized by shifting demographics and blended public/private/nonprofit partnerships.

We believe that responding to these changing conditions requires a new way of thinking about public and nonprofit leadership development.

LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT FOR TRANSFORMATIONAL STEWARDS

Over the last several decades, traditional leader and manager roles, development approaches, and competency profiles have been assumed to be sufficient to support change leadership in the public and nonprofit sectors. However, recent events have exposed many organizations’ (e.g., FEMA, NASA, Red Cross, Smithsonian Institution) weaknesses and apparent leadership failures to implement changes needed in the public interest. Given the changing nature of the required tasks and the available workforce, a reconsideration of approaches for public and nonprofit sector leadership development is in order.

Many training and development programs have begun to incorporate competency models and instructional designs that address change leadership. Yet government and nonprofit leaders and managers often report that such instruction fails to provide the necessary skills and experiences (see, e.g., NAPA 2002, 2003). While collaboration and interorganizational information sharing are taught, the ideal of open, articulate, trusting stakeholders often conflicts with the real operational environments of complex issues and sometimes hostile stakeholders.

Change leaders are often left feeling that survival requires them to vastly scale back or even abandon these collaborative approaches. However, to fulfill their role in protecting the public interest, public and nonprofit leaders have the responsibility to implement change effectively while simultaneously working collaboratively with affected populations to address their interests in a constructive manner. Unfortunately, many current training and development options available to public and nonprofit leaders focus on collections of specific leadership “competencies” that, when developed individually, fail to adequately equip individuals to meet the complex tradeoffs involved in the real world.

Developing transformational stewards requires a holistic approach. Rather than using traditional competency models that represent a collection of more or less separate yet complementary abilities, transformational stewardship begins with a set of attributes that represent the general characteristics of change leadership. These attributes serve as a foundation from which to address specific change requirements. The requirements are summarized in our leadership model’s four processes: diagnosing, strategizing, implementing, and reinforcing change. In each process, the leader must find a practical balance between moving the transformation or change initiative forward and stewarding the stakeholders and organizational interests involved in the issue.

Transformational stewardship development is an approach for public and nonprofit leaders to understand and develop the necessary skills and abilities with regard to the tradeoffs they must make as they endeavor to lead change in the public interest. In this way, stewardship development reframes traditional competencies, validates the core requirements and related skills, and provides the opportunity to apply these tools in the context of real-world challenges. The development aspect stresses the need to balance interests, recognizing the importance of achieving a dynamic equilibrium that reconciles the need for change with the competing needs of stakeholders and the organization.

So how can public and nonprofit organizations develop transformational stewards? We have written this chapter as a practical guide for those in leadership and management positions faced with change-related challenges that require transformational acumen, and also for directors of training and development organizations seeking to create and improve programs aimed at enabling change leadership in their organizations.

THE TRANSFORMATIONAL STEWARDSHIP DEVELOPMENT PATH

As we examine the attributes of a transformational steward and contrast them to current approaches for developing leaders of change, we find three significant shortcomings in the current approaches:

1. Insufficient linkages are drawn between the work of organizational change and the required knowledge, skills, abilities, and developmental efforts necessary to accomplish that work.

2. Explanations of what is and is not involved in organizational change are incomplete.

3. Training and development approaches fail to convey the necessary real-world skills for effective change leadership or to explore the change-related interdependencies and practical challenges involved.

In this section, we outline the components of a transformational stewardship development path (TSDP) as a step toward addressing these deficiencies. Drawing on the transformational stewardship responsibilities as a foundation, the TSDP is a framework that clarifies the nature of transformational leaders’ roles and practices, as well as the fundamental components of leadership development related to leading change and transformation.

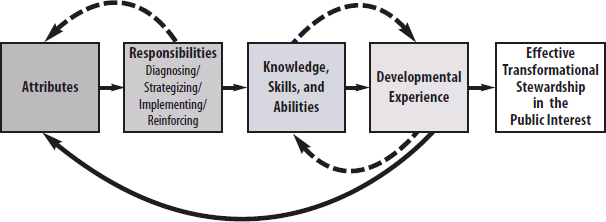

The TSDP organizing framework, depicted in Figure 10.1, includes four interrelated elements: (1) attributes; (2) responsibilities; (3) knowledge, skills, and abilities; and (4) developmental experiences. The elements of the framework articulate the ingredients of transformational stewardship, as well as the “nuts and bolts” necessary for translating this vision into an operational reality in public and nonprofit sector organizations.

The competencies of effective stewardship include the attributes and responsibilities of transformational stewards as well as the required knowledge, skills, and abilities. The path from the attributes to the responsibilities to knowledge, skills, and abilities represents a progression of increasing detail and tactical specificity. Developmental experiences are the experiential aspects required to put transformational stewardship skills into practice.

FIGURE 10.1: Transformational Stewardship Development Path

In our leadership responsibilities model (presented in detail in Chapter 3) we conceptualize the change process in four general phases: (1) diagnosing change risk and organizational capacity; (2) strategizing and making the case for change; (3) implementing and sustaining change; and (4) reinforcing change by creating a change-centric organization. The TSDP addresses leadership development in each phase of organizational change.

Phase 1: Diagnosing Change Risk and Organizational Capacity

The initiating phase of organizational change includes the tasks and related competencies of determining why to change and what to change. This stage begins with an assessment of strategic influences and trends that drive the need for change. Change risks and the organization’s capacity to make the needed changes are then carefully analyzed.

We believe that the four most important tasks of change leaders during this phase are to:

1. Determine the change drivers for the organization within the context of the sociopolitical environment

2. Examine the perceptions of the organization’s stakeholders, both internal and external, likely to be affected by a change

3. Assess the complexity and risks of change and determine how to limit any unanticipated impacts of change

4. Assess the organization’s capacity to undertake change and mitigate change risk.

These four tasks require change leaders to be good at diagnosing and assessing various organizational aspects of the change, and require an integrated, systems thinking approach to the analysis. Our model (presented in Chapter 3) and the list of questions presented in our diagnostic instrument (see Appendix A) provide a starting point for this phase of leading change.

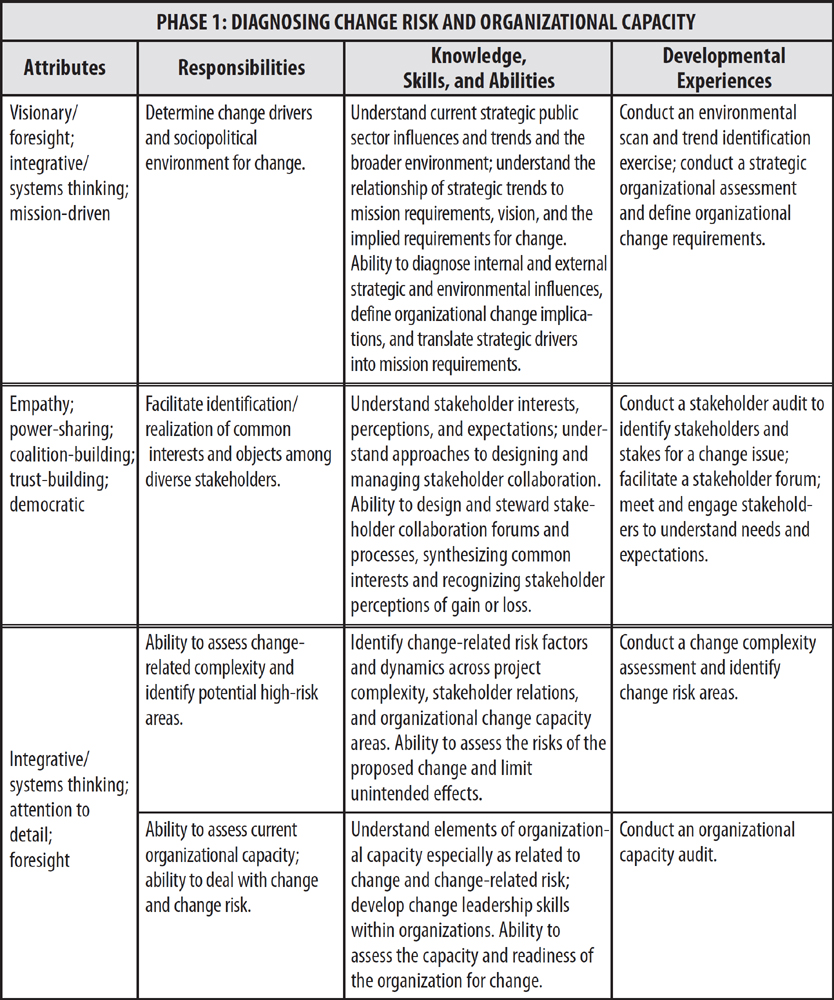

Table 10.1 outlines how attributes contribute to these responsibilities and tasks translate into specific knowledge, skills, and abilities for a change leader. The table also displays how these aspects translate into specific development activities.

TABLE 10.1: Diagnosing Change Risk and Organizational Capacity

The Balancing Challenge

Transformational stewardship in the public interest almost always involves balancing interests and priorities. During this first phase, the balance involves determining how much analysis and preliminary work should be completed before the leader initiates the effort of articulating a change strategy. We have all been afflicted, at one time or another, by the problem of “paralysis by analysis,” where a problem (in this case a proposed change) is so complex and involves so many stakeholders that it is hard for a leader to know where to begin. At the other extreme is the leader who blindly goes forward without a good understanding of the change complexity and risk or a sufficient awareness of the organization’s capacity to accommodate the change.

Effective stewards recognize that a certain level of knowledge is necessary before proceeding, but that they will never understand everything. There is a need to move forward based on a diagnosis of risks, but this must continue as new information becomes available.

The Developmental Agenda

Desired leadership attributes during all phases, including change initiation, are interdependent and integrative in nature. As depicted in Table 10.1, three key attribute clusters are especially important for diagnosing change needs and risk, as well as for assessing organizational capacity for change: (1) visionary perspective and foresight; (2) empathetic ways of relating to others, coalition-building abilities, and a participative democratic approach; and (3) integrative, systems awareness and thinking. While these clusters of attributes are of critical importance across all phases of organizational change, they are essential in helping transformational stewards diagnose the need and nature of change and understand and appreciate the needs of others involved in the process.

The knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary for the diagnosis phase include the following:

• Diagnosing internal and external strategic influences on the change agenda

• Facilitating stakeholder meetings to diagnose stakeholders’ perceptions of gain or loss with various change options

• Assessing the complexity of proposed changes and the likely risks to the organization

• Assessing training needs to strengthen change-leadership skills throughout the organization.

To accomplish these objectives, transformational stewards require an understanding of change-related risks associated with change complexity, stakeholders, and organizational change capacity, as well as an understanding of the interdependencies that link impacts across strategies, organizing structures, work processes, reporting relationships, job/role requirements, and developmental needs.

While it is possible to learn how to assimilate these abilities and skills through reading and taking courses, they are greatly reinforced through experiences, such as conducting an environmental scan or a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) exercise, conducting a stakeholder audit to determine stakeholder perceptions, and conducting a risk assessment of various action options. Individuals striving to become transformational stewards should take advantage of opportunities to become involved in these types of activities in their organization.

Phase 2: Strategizing and Making the Case for Change

Strategizing is probably the most commonly recognized part of the change process. Almost everyone is familiar with the process of “strategic planning,” building “business cases,” and “scoping” a project. Yet, while some of the tasks in this stage are a part of many management vocabularies, the actual nature of transformation-specific activities during this stage is much more detailed than most leadership training. Making the case for change is not easy in any organization, and this challenge can be particularly complicated in government and nonprofit organizations, where rules and procedures may dictate the collaborative process among stakeholder groups. Development of an integrative, collectively supported strategy is important at this stage.

Specific leadership tasks related to strategizing include the following:

1. Creating a vision for change and making the case for change

2. Understanding the total system and how proposed changes may affect various parts of the organization and its stakeholders

3. Designing realistic, comprehensive change strategies and risk-mitigation plans

4. Preparing a business case that stays within capacity limitations and offers maximum return on resources.

These four tasks require the change leader to have the foresight and ability to create and make the case for change, to have a total systems perspective on how the change will affect various stakeholders, and to be detail-oriented in designing the change strategy.

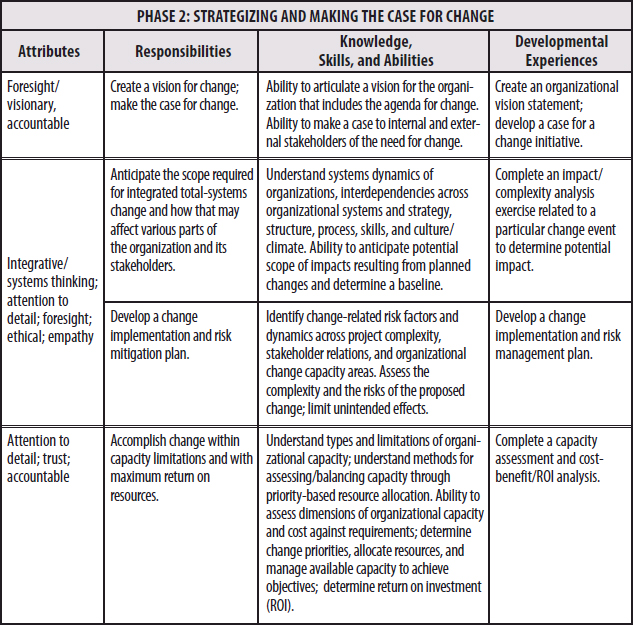

Table 10.2 outlines how attributes contribute to these responsibilities and tasks translate into specific attributes, knowledge, abilities, and skills. The table also displays how these aspects translate into specific development activities that provide the change leader with the necessary background to become more effective in his or her work.

TABLE 10.2: Strategizing and Making the Case for Change

The Balancing Challenge

To successfully initiate change in the public interest, transformational stewards must balance a number of factors: working within structural bureaucratic limitations; satisfying (to the extent possible) the diverse, complex interests of stakeholders; attending to fairness and equity concerns; maintaining appropriate political/trustee accountability; and yet consistently moving forward with a practical change agenda that enhances agency effectiveness. By understanding the nature of making the case for change more completely, transformational stewards can develop a much broader array of practical tools and approaches for creating a balanced process that moves the organization forward yet recognizes and appreciates the complexity of the issues involved.

The limited tenure and frequent turnover of top government leadership also mean that the public sector norm often is a completely new change agenda with each new leadership team. The short-term mindsets of political bosses may create a pervasive anxiety among civil servants regarding organizational change. In many instances, new leadership paves over and even contradicts efforts that civil servants are attempting to implement from previous change efforts. By including an appreciative, empathetic focus throughout the strategic assessment and stakeholder collaboration processes, transformational stewards can more effectively balance various interests and thereby effect positive change.

The Developmental Agenda

During this phase, five key attribute clusters are most important for supporting the actions of initiating change: (1) visionary perspective and foresight, (2) empathetic ways of relating to others and coalition-building abilities, (3) integrative, systems awareness, (4) attention to detail, and (5) adherence to strong ethical standards. These attributes help the transformational steward articulate the need for change and understand and appreciate the needs of others involved in the process, while crafting a realistic change strategy.

The transformational steward must have the ability to identify and assess various strategic influences on the change landscape. Regardless of whether the change is at the organizational, interorganizational, or team level, strategic influences must be translated into change requirements. Developmentally, leaders and managers must understand strategic management principles and the process of determining operational requirements from strategic factors. Even at the most tactical levels, having the ability to translate strategy into the case for change is critical when interacting with stakeholders. The following abilities are especially pertinent:

• Facilitating and creating a common change vision among competing stakeholder interests and perspectives

• Devising and communicating a convincing case for change

• Communicating and collaborating effectively with stakeholders in developing the change strategy

• Accomplishing change initiatives within the capacity limits of the organization and with a maximum return on resources used

• Developing and including effective risk mitigation measures in the strategic plan.

In practice, the strategic process requires transformational stewards to be proficient at conducting stakeholder assessments/audits, planning and facilitating stakeholder forums, and developing a resulting “common” case for change. These tasks require the foundational knowledge of stakeholder relations and the dynamics of collaborative processes, with an understanding of methods for analyzing stakeholder perceptions of their gain or loss with the proposed change. Experientially, the tasks of conducting a strategic assessment, facilitating stakeholder dialogues, determining requirements, and making the case for change all provide practical venues for the initiating competencies to be developed.

While learning and development can come from “book knowledge,” we would argue that the most valuable development is experiential learning—whether in the classroom or on the job. Developing a vision statement, for example, is something you can learn about, study samples, and understand. However, unless you actually participate in the effort to find a common set of values and norms among competing interests, full development is unlikely to occur.

Transformational stewardship requires practice. Understanding “how” to define an organizational vision is no substitute for participating in a vision-setting exercise that incorporates change and transformation.

Similarly, transformational stewards have a responsibility to facilitate identification of the common values, interests, and objectives of the organization’s stakeholders. You can learn how to conduct a stakeholder audit, how to facilitate collaborative processes, and how to develop a “common case for change.” However, unless you have actually attempted to do this, you will have inadequate skills to adapt to the many and various conditions and issues that are likely to arise.

Again, while case studies can provide one method of “gaining experience,” there is no substitute for actually conducting a stakeholder audit and facilitating a stakeholder meeting to develop common interests. Individuals seeking to become transformational stewards should complement their book knowledge by volunteering to participate in these activities, and thereby gain the experience and confidence to fulfill their leadership responsibilities.

Phase 3: Implementing and Sustaining Change

The third set of transformational stewardship responsiblities involves aligning the processes, structures, policies and procedures, roles, and jobs of the organization or team to the change effort. Implementation begins, ideally, when the initial dialogue of why and what to change has led to a collective focus on a particular priority for action. Complete consensus is frequently a luxury for change leaders; nevertheless, general agreement is critical to keep the risks of unanticipated, undesirable consequences to a minimum.

The need to monitor and address change-related risk, in conjunction with the requirement to navigate the interdependencies and systems impacts of changing work and workforce roles, emerges as a challenging task during implementation. As with strategizing and making the case for change, these tasks are supported by the principal attribute clusters of (1) maintaining constant awareness of the “bigger picture” or long-term vision, (2) translating feedback, challenges, and decisions empathetically to maintain a commitment to democratic participation and mutual ownership, and (3) applying an integrative, systems awareness and attention to detail. In this stage, leaders need to communicate effectively, act with transparency and ethical standards, and understand and engage evolving interests and sources of resistance.

Change is inherently unsettling to some degree, regardless of how well it’s led and managed. During implementation, the transformational steward must address the upheaval and uncertainty of change with a consistent and unwavering commitment to maintain focus and clarity, recognize and understand capacity limitations and the needs behind resistance, and facilitate forums for dialogue where everyone owns a part of the process. Specific leadership tasks include the following:

• Establishing transparency, engagement, and collective ownership of the change effort

• Identifying potential obstacles and resistance to change and developing approaches to mitigate those obstacles and resistance

• Setting and stewarding specific change objectives

• Aligning organizational processes, policies, and incentive structures to support the change initiative

• Developing, where necessary, partnerships with other organizations in the change effort

• Managing change-related risk.

Table 10.3 provides a summary of implementation responsibilities and tasks, relating them to specific transformational stewardship attributes, knowledge, skills, abilities, and developmental experiences.

The Balancing Challenge

Over the last 15 years of emerging interest in technology implementation and project management, the prescriptions for change leadership have tended to focus on “managing” the change process in a limited, tactical way. While this focus has pushed leaders and managers to consider the mechanics necessary to manage project-based transformations, it also has somewhat concealed the more holistic aspects of successfully leading and managing in the public interest. In one sense, this technical concentration has been a backlash of sorts to the more “touchy-feely” practices that were proposed by organizational psychologists in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In our view, change leadership during implementation (as in other phases) is neither purely tactical and technical nor exclusively facilitative and subjective.

Rather, as the knowledge, abilities, and skills depicted in Table 10.3 suggest, transformational stewardship requires fluency in the technical and tactical as well as the strategic and traditional aspects of organizational management. We suggest that the dynamic equilibrium proposed by the transformational stewardship concept provides a practical framework for specific, concrete developmental actions.

TABLE 10.3: Implementing and Sustaining Change

The Developmental Agenda

The competency requirements for implementing transformation are relevant for all leaders and managers involved in the implementation process, not just the transformation team. During the initial span of the implementation process, it is critical that the organization’s business process owners and program managers involved in the change actively participate in shaping and guiding the action of transformation. In addition, contractors or other extra-organizational partners should be involved in this step. This “blended-workforce” reality of most change situations involves a core and extended team working together to jointly design and implement the transformational initiative.

Specific abilities change leaders need during this phase include the following:

• Identifying communications needs and designing and carrying out an effective communication strategy

• Establishing mechanisms to create collective ownership of the change effort

• Recognizing and addressing obstacles to the change initiative

• Defining, implementing, and managing clear, credible measures and objectives for the change initiative

• Aligning personnel and organizational resources with the change effort

• Designing and managing partnerships with other organizations necessary for a successful change effort.

Transformational skills are everyone’s responsibility, and widespread transformational competency is a necessity to ensure successful change initiatives. When such capability is absent in the larger community of involved stakeholders and responsibility for change success is restricted to more central officials “at the top,” the tendency to focus on official accountability may overshadow the need for collective ownership. In the federal government, for example, change efforts that involve significant procurement aspects, such as contracting out, can fall into the trap of focusing accountability and risk-mitigation activities on the contract vehicle and the requirement for the vendor to deliver. While contracting relationships and public-private partnerships present their own unique risks, failed implementation is easy to pin on irresponsible contracting, when it is frequently a result of ineffective collaboration among implementation partners.

Two important, complementary transformation skills are worth consideration: (1) the ability to anticipate change impacts and (2) the ability to understand and mitigate transformational risk. Both of these aspects are grounded in the attributes of integrative, systems thinking and attention to detail. Transformational stewards must have the ability to draw on the explicit, objective-driven definition of the project and then deduce the needs for process, policy, procedure, structure, and competency changes. This ability requires that the transformational steward be proficient in employing a systems approach to identifying the primary and secondary impacts of the change initiative.

In addition to the transformational stewardship competencies related to change scope and risk identification, successful transformational stewardship during implementation requires an empathetic connection with the stakeholders participating in the initiative. Through consistent communications, democratic, participative decision-making, issues resolution, and obstacle/resistance awareness, the transformational steward can strike a balance that builds and sustains trust and commitment while still moving forward with change.

Effective implementation and sustaining change require a combination of foundational knowledge and practical experience. The complementary and reciprocally reinforcing nature of these two components is necessary to provide the transformational steward with a solid base for applying competencies.

For example, one key responsibility of transformational stewardship is creating a transparent environment in the organization with informed and involved stakeholders. From books, we can learn about various approaches to communications, how to develop channels of information flowing both down and up throughout the organization, and how important it is to involve others in the implementation of change and transformation. But for a transformational steward, there is no substitute for actually facilitating specific transformational planning, decision-making, and risk management efforts. Training and development programs can lay the groundwork, but as in many endeavors, there is simply no substitute for hands-on experience.

Phase 4: Reinforcing Change and Stewarding Growth and Renewal

The final phase of transformational stewardship is reinforcing the change effort and stewarding the growth and renewal of both the organization and its individual leaders. In this phase, all the transformational stewardship attributes are in play; however, some are more important to the organization while others are more important in the growth and renewal of individuals. This phase is slightly different from the other phases, as leaders focus on building transformational capability both individually and organizationally in addition to focusing on the successful completion of the change initiative that is underway. The role of the transformational steward includes responsibility for accomplishing specific change initiatives and for moving the organizational culture to be more change-friendly.

Specific responsibilities of transformational stewards include the following:

• Facilitating organizational learning, improvement, and innovation

• Establishing an environment of ethical collaboration, information-sharing, and collective ownership

• Establishing change implementation practices, measures, structures, and policies to reinforce change efforts

• Developing change-centric leaders within the organization

• Developing a transformational ethic in approaching their responsibilities

• Nurturing their own development and growth as transformational stewards.

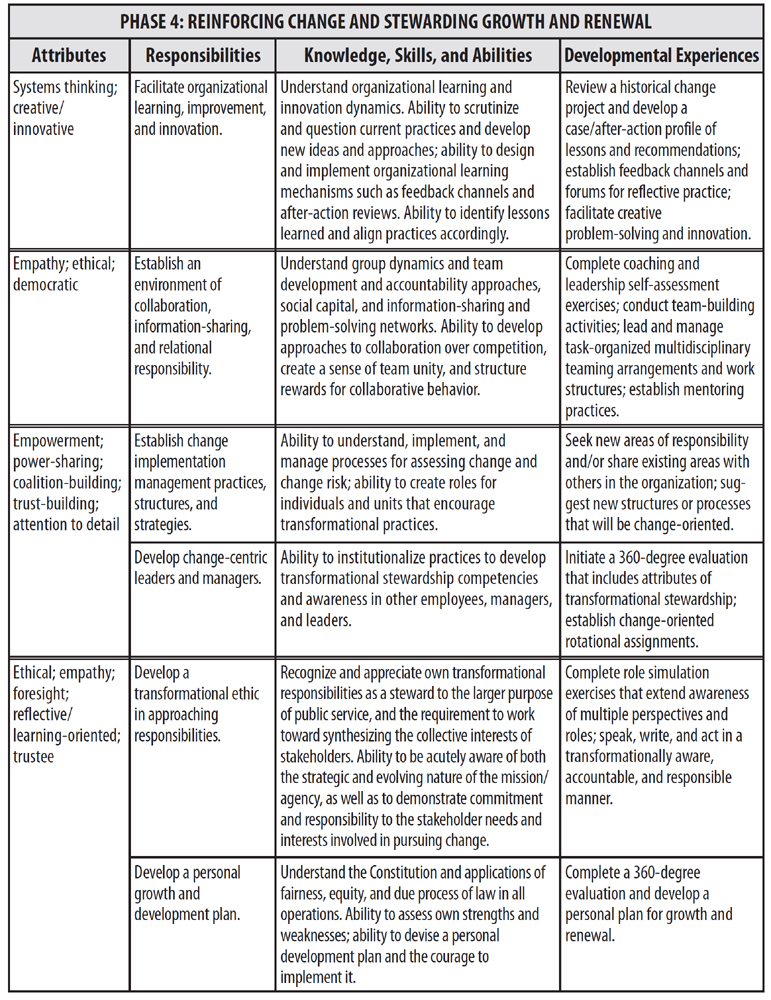

Table 10.4 provides a breakdown of the competencies and development dimensions for the growth and renewal of leaders and their organizations.

The Balance Challenge

The key challenge during this phase for both the organization and the individual is balancing the need for continuity with the need to improve and evolve. Constant change that occurs without meeting the need for closure, recognition of success, and establishment of process maturity is unhealthy and disruptive. Yet, neither the organization nor the individual can remain complacent, with an imbalance toward security and comfort at the expense of evolving to better meet stakeholder and customer needs. Growth and renewal in the public interest ultimately involve balancing tradition and consistency while steadily scanning for improvement opportunities and creative solutions.

TABLE 10.4: Reinforcing Change and Stewarding Growth and Renewal

The Developmental Agenda

We have listed six broad areas of responsibility for transformational stewardship for renewal and growth. For the organization, transformational stewardship responsibilities include creating a learning organization; enhancing ethical collaboration; creating change-centric practices, systems, and strategies; and developing other change leaders. The responsibility to nurture transformational capacity requires change-centric ways of perceiving and relating (e.g., creativity, comfort with ambiguity, integrative/systems thinking) as well as interpersonal attributes that emphasize extending the concept of transformational stewardship throughout the organization (especially building trust, empowering, and power sharing). These attributes help transformational stewards create organizations that are open and adaptive to change, with people throughout the organization willing to assume leadership roles in the constant renewal of the organization.

Transformational stewards also are responsible for their own nurturing—which in the crush of work often gets less attention than it should. In this case, the continued development of a person’s “inner-personal beliefs and values” is vital. These traits include ethical reasoning, self-reflection, empathy, vision or foresight, and creativity. In addition, attributes related to developing a change-centric operational mindset also are important (especially attention to detail, comfort with ambiguity, and integrative/systems thinking). The development of these attributes often comes only when a person is willing to take the time to step back and assess where he or she is, what is going well, and what could be improved. This reinvigoration should be something that continues throughout a person’s life and career.

Personal retreats, conferences, sabbaticals, university courses, journal writing, and ongoing dialogue with a mentor are all methods of self-improvement that have their advocates. Similarly, assessment instruments (such as 360-degree evaluations) that assess an individual’s or team’s transformational skills are often useful to help leaders become more aware of their transformational proficiency. (Appendix B provides an illustration of one such 360-degree evaluation.) These methods can be applied formally through organizational training and development programs, or informally by individual leaders and managers seeking to become more confident and effective. Ideally, a combination of formal and informal means can be employed to facilitate skill development.

Each of these responsibilities is associated with particular knowledge, skills, and abilities. Just as with the attributes, there is some overlap in this area; however, we believe there is enough differentiation to provide guidance to a person wanting to exercise transformational stewardship. For example, the responsibility of creating a learning organization is associated with the ability (and willingness) to scrutinize and question current practices and to be open to new ideas and concepts. It means creating feedback mechanisms within the organization to encourage learning. It means not punishing mistakes, but learning from them. Reflective practice requires developing specific skills and implementing realistic approaches for assessing experience, recognizing lessons, and taking action to address deficiencies.

Other abilities include the following:

• Becoming more risk-aware, perceiving strategic and operational change initiatives in terms of both opportunity and risk

• Assessing and creatively managing risk to minimize its potential negative consequences

• Enhancing ethical communication and authentic collaboration within the organization or network

• Engaging in personal learning and growth.

Transformational stewards are responsible for enhancing ethical communication and authentic collaboration within their organizations. To accomplish this, stewards must understand workplace standards, good ethical practices, and approaches to mentoring and individual development, as well as how to structure team and work collaborative incentives. However, this knowledge serves as just the frame for actually providing the mentoring, coaching, and individual and team development—practices that all managers and leaders should follow, particularly those seeking to practice transformational stewardship.

When transformational competencies and experiences are recognized explicitly as requirements for promotion, leaders and managers are much more likely to consistently seek out and commit to investing time and effort in pursuit of such skills. As an example, in the early days of the “Six Sigma” process improvement initiative at General Electric, Chief Executive Jack Welch established the requirement that, in order to be promoted into a management position, an individual had to complete process improvement and reengineering training and had to accomplish a successful transformation project (Cavanagh, Neuman, and Pande 2002). The result was not surprising: Would-be managers got the training and went out in search of opportunities to lead change.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CHANGE LEADERS

We believe that the traditional approaches to leadership development in the areas of change and transformation are insufficient in today’s challenging public service environment. Transformational stewardship is a way of understanding change leadership in the public and nonprofit sectors. We have identified specific attributes that we think are closely aligned with this concept and have indicated how they relate to the various phases of change and transformation: diagnosing, strategizing and making the case for change, implementing and sustaining, and growth and renewal. Finally, we have presented a developmental framework relating attributes and the knowledge, skills, and abilities to the responsibilities and tasks required of effective transformational stewards.

Transformation in the public interest is difficult, even with the necessary skills and abilities. However, the ability to lead change successfully is such an important task that we cannot continue to merely “wing it” and rely on traditional training for public and nonprofit leadership and management. The basic responsibilities, abilities, and skills that we have identified are necessary ingredients to the success of all organizations, and particularly those entrusted to serve the public interest. Approaching this challenge in an informed, comprehensive manner is critical, and a combination of enhancing transformation knowledge and learning from developmental experiences is needed to make talented leaders.

SUGGESTED READINGS ON DEVELOPING TRANSFORMATIONAL STEWARDS

Thompson argues that we should not separate our personal and professional selves; both have to be guided by our inner spiritual values. Development of the individual spirit, he contends, can lead to both personal and organizational fulfillment. The author’s research and illustrations provide a compelling case for the “fruits of the spirit.” Questions and exercises for further reflection are included to enable readers to apply the author’s concepts to their personal lives.

Goleman, author of the groundbreaking Working with Emotional Intelligence (New York: Bantam, 1998), which advanced the concept of a leader’s emotional intelligence (EI), teams with McKee and Boyatkzis to further explore the concept and provide readers with an approach to leadership development. Their approach includes assessing, developing, and sustaining personal EI over time, cultivating “resonant” leadership throughout teams and organizations, and building emotionally intelligent organizations. Included is Boyatkzis’ “theory of self-directed learning,” which provides a feedback process for leadership development.

In his 1989 book, Managing as a Performing Art (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass), Vaill coined the term “permanent white water” to characterize the turbulent environment of modern organizations. In this book, Vaill argues that traditional management programs have not equipped managers to be leaders in a changing environment. If managers are to navigate this environment, they must make continuous learning part of their personal being. Such learning encapsulates risk-taking, self-direction, and the integration of life’s lessons from both our personal and professional lives.

Bennis, who with Burt Nanus wrote an important book on leadership, Leaders: The Strategies for Taking Change (2nd ed., New York: Harper-Business, 1997), teams up with Joan Goldsmith to fashion a workbook for those who want to become more effective leaders. The authors take the reader through a set of practical exercises for understanding their concepts of leadership and learning modes and becoming more effective leaders in three broad areas: creating and communicating a vision, maintaining trust though integrity, and realizing intention through action. The workbook also contains an excellent bibliography of resources on leadership development.

This chapter is adapted from James Edwin Kee, Kathryn Newcomer, and Mike Davis, “A New Vision for Public Leadership: The Case for Developing Transformational Stewards.” In Innovations in Public Leadership Development, Ricardo Morse and Terry Buss, editors. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 2008.