Ethical and Legal Considerations

Introduction

Before conducting any kind of user activity, there are a number of ethical and legal considerations you must be aware of. You are responsible for protecting the participants, your company, and the data you collect. These are not responsibilities that should be taken lightly. This chapter applies to all readers. Even if you are doing “just a little research,” if it involves human participants, this chapter applies to you. In this chapter, we will inform you of what you need to know before conducting a user activity to make sure you collect valuable data without legal or ethical harm. These are general guidelines but you need to be aware of your local laws, practices, and regulations.

Policies vs. Laws vs. Ethics

People often conflate their company’s policies, laws, and ethical guidelines. It is important to understand the differences. Policies are set forth by your company, often with the goal of ensuring employees do not come close to breaking laws or just to enforce good business practices. For example, many companies have privacy policies stating how they handle customer data. The specifics of those policies may differ among companies. California is the only state that requires a company to post their privacy policy if it is collecting personal information from any California resident; however, it is best practice to post one’s privacy policy, regardless of where the customers reside.

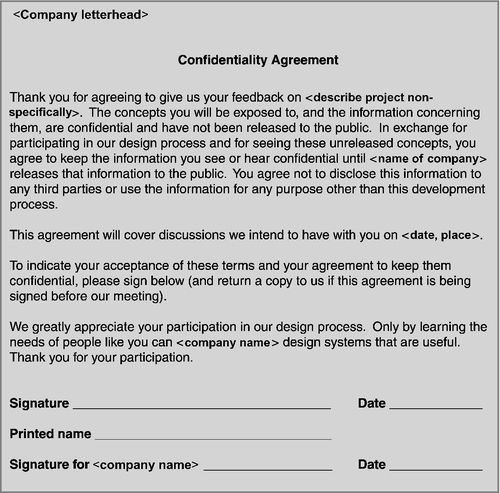

Laws are rules set forth by the government, and everyone must comply with them, regardless of where they work. United States tax laws, for example, mandate how much a company may pay an individual per year before the company must file forms with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). This is important to know and track if you plan to provide incentives (cash or otherwise) to participants in your studies. Nondisclosure or confidentiality agreements (NDAs or CDAs) are legally binding agreements that protect your company’s intellectual property by requiring participants to keep what they see and hear in your study confidential and hand over the ownership of any ideas, suggestions, or feedback they provide. We will discuss these in a little more detail later (see Figure 3.1).

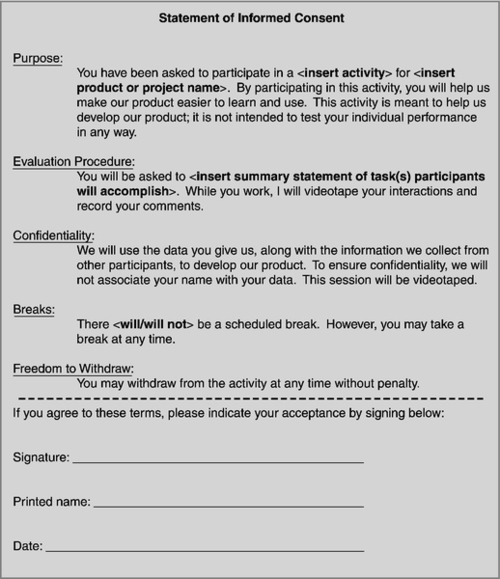

An informed consent form is an agreement of your ethical obligations to the participant (see Figure 3.2). It may not be legally binding, but it is absolutely ethically binding. Keep in mind that you likely cannot develop one informed consent form for all studies since not every study is identical. You should evaluate the risks to the participants and the elements you need to inform them of for every study. Another example of an ethical obligation is to be transparent about how a participant’s data will be handled. Who will be able to see it within the company (e.g., just the researcher, the entire development team, anyone in the company who is interested)? Will the participant’s name and other identifiable information be associated with their data (e.g., video of the session, transcript from the interview)? There is not a law requiring you to inform participants of this and your company may not have a policy about this, but research ethics state you should inform them.

Ethical Considerations

Having strong ethical standards protects the participants, your company, and your data. Every company/organization that gathers data from people should have a set of policies and practices in place for ethical treatment. If your company does not, then you should implement them for your group or organization. Remember: you are acting as the user’s advocate. It is your responsibility to protect the participants’ physical and psychological well-being when they have kindly volunteered to help you by sharing their time, experience, and expertise. In the case where the participant is a customer, you have the added responsibility of protecting and promoting the customer’s relationship with your company. A poor experience in your usability activity could result in lost revenue. You can be certain that your company will not support future usability activities once that has occurred.

As a final (but important) consideration, you must protect the data you are collecting. You do not want to bias or corrupt the data. If this happens, all of your time, money, and effort will be wasted when the data have to be discarded. The data you use in making design decisions must be valid and reliable or you risk doing more harm than good; poor data can result in bad design decisions. With this being said, if data are compromised, it is always possible to recruit more participants and collect more data, but it is much harder to restore the dignity of a participant who feels coerced or ill-treated or to correct a damaged business relationship. So keep in mind that the participants’ well-being is always your top priority. Figure 3.3 illustrates this priority by placing the participant at the highest point.

In this section, we discuss some of the key ethical considerations to keep in mind when running any usability activity.

Do No Harm

At the core of all ethical guidelines are the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence. That is a fancy way of saying that your research must be beneficial and do no harm. But in order to protect your participants from harm, you must first understand all of the potential risks your participants may encounter in your study. Right now, you are probably thinking, “It’s a card sorting study for a website. What possible risks could there be?!” The risks could be perceived by the participant (e.g., “The video of my study will get leaked and everyone will laugh at it”) or actual (e.g., the product is so hard to use that the study is actually pretty unpleasant to use). The risks can be benign (e.g., boredom), physical (e.g., thumb discomfort using a newly designed game controller), emotional (e.g., anxiety about account security in a phishing study), or worrisome (e.g., the participant learns of a new feature being developed that causes him or her to be concerned after the study). You must find a way to mitigate all of the risks, real and perceived, and address them in your informed consent to the participant. Using the example of the game controller, if there really is no way you can redesign the controller to avoid the thumb discomfort, then first, you should help mitigate it by limiting the time the participant uses it (e.g., short test sessions, frequent breaks). Second, you must notify participants of the risk at the beginning of the study and inform them that they are free to take a break or quit at any time they feel discomfort. Be aware that it is also possible that removing an intervention you introduced in your study can cause harm (e.g., giving participants an easier tool for their jobs then removing it after the study).

The Right to Be Informed

It is only when the participants fully understand the risks and what is going to happen in the study that they can be willing (not deceived) participants. For example, since it is not uncommon for participants to worry that many people are going to see the video of their study and possibly laugh at their mistakes, you should inform all participants (not just the ones who ask) how you will control access to the video and data.

Participants have the right to know the purpose of the activity they are involved in, the expected duration, procedures, use of information collected (e.g., to design a new product), incentives for participation, and their rights as a participant of the study (e.g., freedom to withdraw without penalty). You should also inform participants that the purpose of the study is to evaluate the product, not them, and any difficulty they encounter is a reflection on the product, not them. This information should be conveyed during the recruitment process (refer to Chapter 6, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Recruitment Methods” section, page 139) and then reiterated at the beginning of the activity when the informed consent form is distributed and signed by the participants. The participants sign this form to acknowledge being informed of these things and agreeing to participate. If you are working with participants under the age of 18, a parent or guardian must sign the informed consent form; however, the minor must still be verbally informed of the same information “in terms they can understand” and provide their consent. If the minor does not consent, it does not matter that the parent has already agreed.

Deception should be avoided unless the benefits greatly outweigh any potential harm. You may not want to reveal every aspect of your study up front to avoid biasing the participant’s response, but the participant should not be tricked into participating if you believe he or she never would have agreed to sign up had he or she known the details of the study. For example, if you want to conduct a brand-blind study (i.e., the creator of the product is not identified) or sponsor-blind study (i.e., you do not wish to reveal that you are conducting an analysis of your competition’s product), a third-party recruiting for your study could provide participants with a list of possible companies (including yours and your competitors) that are conducting the study. The participants should then be asked if they have any concerns or issues with participating in studies by any of those companies. At the end of the study, the evaluator should reveal the true sponsor.

If participants have a misperception about the purpose of the activity (e.g., believing that it is a job interview), the participant must be corrected immediately and given the opportunity to withdraw. Participants should also have the opportunity to ask questions and to know whom to contact with further questions about the study or their rights.

Permission to Record

It is common to record research studies as it allows stakeholders who could not attend to see what happened, and it allows researchers to focus on what is happening without having to take copious notes during the study. Before recording the voice or image of any individual, you must obtain permission. This can be accomplished with the consent form in Figure 3.2. The recording must not be used in a manner that could cause public identification or harm. Inform participants during recruitment that they will be audio or video recorded. Some individuals are not comfortable with this, so you do not want to wait until the participant arrives to find that out. Although it is rare, we have had a couple of participants leave before the activity even began because they refused to be recorded. If you would like to use recordings of a participant beyond your research team, you must seek additional permission. For example, if you would like to show a video of participants in a study at a research conference, you could let participants “opt in” to a recording by adding the following to your consent form or permission to record form:

Please select ONE of the following options for use of audio/video recordings by initialing your preference below:

• If you are willing to allow us to use a recording of any portion of your interview, please initial here___. If you have initialed here, we may use a portion of your interview in a presentation, for example, but you will never be identified by name.

• If you would prefer that we use information from your audio/video recording only in transcribed form (rather than as an audio or video clip), please initial here ___.

On the flip side, with the use of remote evaluations, you must inform users that they are not allowed to record the sessions or take any screenshots. Remember to include this in your NDA (refer to “Legal Considerations” section on page 76 to learn more about nondisclosure agreements).

Cartoon by Abi Jones

Create a Comfortable Experience

Participants in your study should never feel uncomfortable, either physically or psychologically. This includes simple things like offering regular bathroom breaks, beverages, and comfortable facilities. And of course, this includes treating the participants with respect at all times. If your study involves minors, keep the tasks age or skill appropriate and keep the sessions shorter to allow for shorter attention spans. If your user research activity involves any type of completion of tasks or product use (e.g., having users complete tasks on a competitor product), you must stress to the participant that the product is being evaluated, not them. Using a particularly difficult or poorly designed product can be stressful. If a participant performs poorly, never reveal that his or her answers are wrong or that something was done incorrectly. You need to be empathetic and remind participants that any difficulties they encounter are not a reflection on their own abilities but on the quality of the product they are using. For example, if participants blame themselves for their difficulties (e.g., “I am sure the way to do this task is obvious but I am never good at this kind of thing”), you can reply, “Not at all! The difficulty you are having is the fault of the website, not you. If you were at home and would normally quit at this point, please don’t hesitate to say so!”

Appropriate Language

Part of treating participants with respect is to understand that they are not “subjects.” Historically, this was how participants were described. It was not meant pejoratively, but the APA publication Manual referred to earlier recommends that you replace the impersonal term “subjects” with a more descriptive term when possible. You do not want to use the participants’ names for reasons of anonymity (see below); however, participants, individuals, or respondents are all better alternatives to “subjects.” Of course, you would never address a participant by asking, “What do you think, Subject Number 1?” You should also show the same respect when speaking about them in their absence or in documentation. Never make light of participants (e.g., stakeholders laughing at participants in the observation room or after the study). The people who agree to provide you with their time and expertise are the foundation of a successful study. Without them, nearly every activity listed in this book would be impossible. We strongly recommend that readers review the sixth edition of the APA Publication Manual to better understand language bias, both written and spoken.

Anonymity vs. Confidentiality

Anonymity and confidentiality are also terms that people often conflate. To keep a participant’s participation in your study completely anonymous means not having any personally identifying information (PII) about them. Since we typically conduct screeners to qualify participants for our studies, we know their names, e-mail addresses, etc. Instead, we typically keep their participation confidential. We do not associate a participant’s name or other personally identifiable information with his or her data (e.g., notes, surveys, videos) unless the participant provides such consent in writing. Instead, we use a participant ID (e.g., P1, participant 1). It is important to protect a participant’s privacy, so if you are unable to provide anonymity, at a minimum, you must keep his or her participation confidential.

If the participants are employees of your company, you have a special obligation to protect their anonymity from their managers. Never show videos of employees to their managers (refer to Chapter 7, During Your User Research Activity, “Who Should NOT Observe” section, page 162). This rule should also apply to their colleagues. You should also be aware that the requirements around handling the personally identifiable information of minors differs per country.

The Right to Withdraw

Participants should feel free to withdraw from your activity without penalty at any point in the study. If a participant withdraws partway through the study and you do not pay the person (or pay only a fraction of the original incentive), you are punishing him or her. If you are conducting an economic behavioral study, a participant’s choices during the study actually impact the size of their incentive. However, in most HCI studies, you are obligated to pay all participants the full incentive, whether they participate in the full study or not. One way to make this crystal clear to participants is by providing them with their incentive as soon as they arrive at the lab. As you inform the participants of their rights as stated in your informed consent form, you can point out, “I have already provided your incentive, and that is yours to keep, regardless of how long you participate in the study.” In all of our years of conducting user research, the authors have never had a case of a participant taking advantage of the situation by arriving to get his or her incentive and then just leaving.

Appropriate Incentives

You should avoid offering excessive or inappropriate incentives as an enticement for participation as such inducements are likely to coerce the participant (refer to Chapter 6, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Determining Participant Incentives” section, page 127). We realize the incentive is part of the reason why most people participate in research activities, but the incentive should not be so enticing that anyone would want to participate regardless of interest. The main reason for participation should be interest in influencing your product’s design. In other words, do not make participants an offer they cannot refuse. This is context-dependent so the amount of the incentive you offer in the United States will be different from the amount you offer in India, for example, and the amount you offer for a highly skilled worker (e.g., doctor, lawyer) may be different from what you offer a general Internet user. This is an especially important point to understand if conducting international research where the amount you offer for one hour of participation in the United States is equivalent to a month’s salary in another country. You may feel you are doing a service by offering such an excessive incentive. This is not only coercive, however; you also risk pricing out other local companies with your inflated incentives.

The incentives should also be accountable (i.e., no cash). In other words, you need to be able to track that the incentive was given to the participant. This is not an ethical guideline but is good practice in any company. You could offer AMEX gift checks, Visa gift cards, or other gifts. You will need to investigate what type of incentive is most appropriate for each country or region you are conducting research in (e.g., mobile top-up cards, M-Pesa). Do not forget to track the amount you provide per participant (see earlier tax discussion).

You should speak with your legal department before recruiting paying customers and offering them any incentives for your studies. Many companies, especially those in the enterprise space, do not provide monetary incentives to paying customers, or they may prefer to offer only logo gear of nominal value (e.g., t-shirts, mugs) to avoid the appearance of offering bribes for business. Make sure you know your company’s policies. You should never offer incentives to government officials. To many people’s surprise, US public school teachers and state college/university employees are considered government employees. If you are developing a product for teachers, you obviously will want to include them in your study, so you may need to speak with your legal department to determine how to provide a benefit of some kind for these participants. Outside of the United States, it can be much trickier to know who a government employee is, so check with your legal department when planning to do studies outside your home country.

One question that many people have is how to compensate for longitudinal or multipart studies. If you are concerned about high drop-off or participants not completing all parts of your study, you can break your study into smaller pieces with smaller incentives. You can decide which and how many of the pieces of the study you want to invite participants to complete, and they can decide which ones to opt into. One concern here is the appearance of coercion to complete the study. Make sure that your incentive structure does not unduly influence participants from withdrawing from the study. For example, if you set up an incentive scheme where participants would receive $1 per day every day for five days and then an additional $100 if they completed all five days, this might prevent them from feeling they could withdraw from the study after two days. A better strategy would be to pay them $20 per day for each day and then a $5 bonus if they completed all five days.

Valid and Reliable Data

The questions you ask participants and your reactions to their comments can affect the data you collect. In every activity, you must ensure that the data you collect are free from bias, accurate, valid, and reliable. You should never collect and report data that you know are invalid or unreliable. If you suspect that participants are being dishonest in their representation, regardless of their reasons, you should throw away their data. You must inform stakeholders about the limitations of the data you have collected. And of course, you must never fabricate data.

Along the same lines, if you learn of someone who is misusing or misrepresenting your work, you must take reasonable steps to correct it. For example, if in order to further an argument, someone is inaccurately quoting partial results from a series of studies you conducted, you must inform everyone involved of the correct interpretation of the results of the study. If people question the integrity of your work, your efforts are all for naught.

You should remove yourself from situations in which a conflict of interest may affect your actions. For example, it is ill-advised for one to personally collect feedback on their own designs because objectivity is affected. Although many companies hire individuals to act as both designer and researcher with the expectation that they will evaluate their own designs, this is unwise. Due to your bias, your results will not be valid. However, if you find yourself in the situation where you are doing research on your own designs, be aware of your own bias. By recognizing this, you can attempt to mitigate it. If possible, try to put some temporal distance between the design phase and the research phase, for example. Alternatively, set up your study so you have less influence over the results (e.g., quantitative survey data require less interpretation than qualitative interview data).

Acknowledge Your True Capabilities

You should provide services, make recommendations, and conduct research only within the boundaries of your competencies. In your job role, this may require you to seek out additional training or resources. You should always inform individuals of the boundaries of your knowledge and skills, should you be placed in a situation that is outside your areas of expertise. For example, if you are asked to run a usability evaluation and you know nothing about usability, you should not attempt to wing it. If you do not have the time to learn what is necessary to run the activity, you should contract it out to a professional who can.

We provide the training and tools in this book to help you learn how to conduct user research, but we also encourage you to supplement this with additional courses and mentoring.

Finally, you should not delegate work to individuals who you know do not have the appropriate training or knowledge to complete the task. This also means you cannot hand over your ethical responsibilities to a third party. Anyone that you hire to recruit participants or conduct studies for your company should adhere to the same ethical standards you observe. If a vendor is unhappy about your requirement to provide a list of potential sponsors during the screening stage for a brand-blind study or to pay participants in full even if they withdraw partway through a study, find another vendor. If a vendor warns you that a certain user type will be difficult to recruit and thus may need to be “creative,” ask what “creative” means. Turning a blind eye to how a vendor recruited those users is engaging in unethical behavior and is putting the participants, your company, and your data at risk.

Data Retention, Documentation, and Security

Retain the original data collected (e.g., screeners, raw notes, videos) only for as long as it is required by your organization, industry, country, or region. This may be the period of time that you are working on a particular version of the product or it may be several years. You will want to retain the data in case you need to reference it at a later date for clarification purposes. It can also be very useful to provide continuity in the event that someone must take over research support for the product. In academic settings, the funder of your research (e.g., the National Science Foundation) and/or the IRB likely have rules about how long you must keep your data after a study has been completed. After that, to protect user confidentiality, you should destroy it. In the meantime, you are responsible for ensuring the data are secure and only those that need access have it. One strategy Kelly uses in most of her work is to de-identify data as soon as possible after collection. Once participants have been paid, there is rarely a reason to need to know their real name, birthday, address, or phone number. Even if you do have to collect this information, you should not store it with study data. Instead, keep any of this personal information stored separately. That way, even if others were able to access your data, they would not be able to match participants’ study data to their names.

It is important to accurately record the methods of any study you conduct (refer to Chapter 15, Concluding Your Activity, “Reporting Your Findings” section, page 463). This will allow anyone to understand exactly how you collected the data and what conclusions were drawn. This history is also critical for all stakeholders—and especially anyone who is new to the product team. You would be amazed at how often a “brand new” idea really is not brand new. Those reports can prevent repetition of the same mistakes every time a new team member comes on board.

Debrief

If a participant was not aware of the full intent of the study (i.e., its purpose) before it began, you should attempt to debrief him or her about the nature, results, and conclusions of the study. Typically in a user research activity, the participants are told why the information is being collected (e.g., to help design a usable product, to learn more about a domain, to collect user requirements), so this is not an issue. However, in the case of a customer, this could mean asking participants at the end of the study whether they wish to be contacted regarding the results of the activity once the product has shipped. You should also give participants a way to redress any concerns they may have if they feel they have been deceived or poorly treated. For example, offer to allow them to speak with your manager or, if the issue is more serious, your company’s legal department.

Legal Considerations

It is very important for you to protect your company whenever you run any kind of research activity. You do this not only for ethical reasons but also to protect your company from being sued. By following the basic rules of ethics discussed above, you should avoid such circumstances.

In addition to protecting your company from lawsuits, you also want to protect the confidentiality of your products. As a company, you do not typically want the world to know too early about the latest and greatest products you are developing. In most cases, this information is deemed highly confidential. When you run user research activities, you are exposing people outside of your company to a potential or existing product. It may not be the product itself, but ideas relating to that product. Regardless, it is imperative that your participants keep the information they are exposed to confidential so that it cannot be used to create competitor products. In order to protect your company’s product, you should have all participants sign an NDA. This form is a legal agreement in which the participant signs and thereby agrees to keep all information regarding the product and session confidential for a predefined period. It does not stop a participant from leaking the confidential information, but it provides your company with legal recourse in the event it happens. This agreement also typically states that any ideas or feedback the participant provides becomes the property of your company. You want to avoid participants later requesting financial compensation for an idea they provided in your study, regardless of whether it really was the source of your great new product enhancement. Work with your legal department to create an agreement that is appropriate for your purposes and to ensure that it will protect your company. Ideally, it should be written in terms a layperson can understand, but you are still obliged to explain the terms of the agreement (especially when the participant is a minor) and answer any questions. Although a parent or guardian must sign an NDA on behalf of a minor, the minor must still understand what is being asked of them and the consequences of violation.

Figure 3.1 shows a sample NDA to help you get a sense of the kind of information that this document should contain. Again, we do not advise that you take this document and start using it at your company. It is imperative that you have a legal professional review any NDA that you decide to use.

Although it is written with the assumption that you are conducting the study in person with the participant, some of the methods in this book can be conducted remotely (e.g., diary study, survey, remote usability test). Regardless of whether you are face to face with the participant or not, all of the legal and ethical issues discussed here apply. In remote studies, you will likely need to provide the following:

■ An e-mail address or phone number where participants can contact you with any questions before and after a study. You need to answer those questions as completely as you would in an in-person study and do it quickly.

■ Clear informed consent laying out all of the participants’ rights, purpose of the study, permission to record (if applicable), how their data will be handled, risks, and benefits.

■ Mechanisms to avoid risk. Going back to the example of the game controller potentially causing thumb discomfort, you may need to create time limits to prevent participants from using the controller for too long and make it easy for them to take breaks as needed.

■ Online NDA for participants to click and accept or easy mechanism for them to read, sign, and return the NDA. Remember that not everyone has access to a scanner, so you if you are forced to use paper documents, provide a self-addressed stamped envelope for participants to mail you their NDA.

■ Ability to quit the study at any point while still easily receiving their incentive.

■ Appropriate incentive that the participant can quickly and easily receive. For example, if you are conducting a diary study with different groups of participants over several weeks, participants should not have to wait until your entire study is complete before receiving their incentive. Instead, you need to provide the incentive (ideally) as soon as participants begin the study or shortly after they finish their participation.

■ Debrief mechanism following the study if there is anything you hid from the participants (e.g., study sponsor).

Pulling It All Together

In this chapter, we have introduced you to the legal and ethical issues to take into consideration when conducting a user research activity. By treating participants legally and ethically, you will protect them, your company, and your data—all of which are critical for successful user research. This involves always obtaining informed consent from your participants, and to do that, you must verify that participants:

■ Understand what it means to participate

■ Comprehend and agree to any risks

■ Understand how their personal data will be protected

■ Have a meaningful chance to ask questions

■ Are able to seek redress if they are unhappy

■ Know they can withdraw without penalty at any point in time

Without the participants, you could not conduct your study. Remember the participants in your study must be treated with the utmost respect. This applies to all methods described in this book.