During Your User Research Activity

Introduction

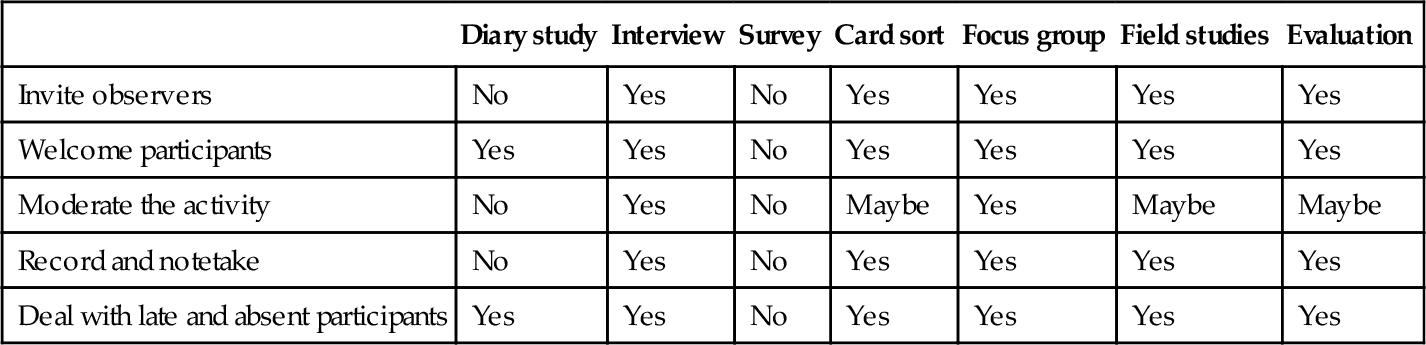

In the previous chapter, you learned how to lay the groundwork and prepare for any activity. In this chapter, we cover the fundamentals of executing a successful user research activity. Because user research activities can occur in the lab or in the field, in person, or via e-mail, audio chat, or video chat, how much you, as the researcher, have to do “during” an activity can differ greatly depending on which activity you have chosen (see Table 7.1). For example, during an online survey, you simply keep an eye on the quality of the data as they flow in. On the other hand, during an in-person focus group, you are responsible for greeting participants, keeping participants energetic, ensuring you are eliciting quality discussion, and making sure all your recording equipment is functioning properly. It takes a lot more preparation and energy during a focus group than it does during a survey!

Table 7.1

Level of researcher activity during a typical study by type

| Study type | Level of activity |

| Diary study | Low |

| Interview | High |

| Survey | Low |

| Card sort | Medium |

| Focus group | High |

| Field studies | Medium |

| Evaluation | Medium |

Besides differences between activities, there are also different choices you can make about what will happen during your activity. For example, you can choose to conduct your session with only one person at a time (individual) or with many people at a time (group). You can choose to conduct a session face-to-face (in person) or via a mediated communication channel, such as video chat (remote). You can choose to conduct your activity in a space specifically set up for user research activities (lab) or in the home or office of a participant (field). Finally, you can choose for your portion of the activity to be at the same time as the participant, allowing interaction (synchronous), or at different times (asynchronous).

Because there are so many options, some of the recommendations in this chapter will not fit exactly with every activity as you have designed it. See Table 7.2 for a quick guide about which sections of this chapter are most applicable to each activity type. We have focused most of our discussion on activities that can be tricky and require high levels of researcher participation during the activities, which are usually those that are in person, are synchronous, and occur in groups. However, all of the recommendations can be used as a guide no matter what type of activity you are conducting. For example, if you are conducting your research activity remotely (e.g., remote card sort), you will need to vary the way you welcome participants, get informed consent, and provide incentives to fit your format. Even though you will not meet participants in person, you will still need to welcome them, get informed consent, and pay them. In this case, instead of welcoming participants in person verbally, you will need to do this by displaying text on a welcome screen; instead of having participants sign a paper consent form, have them read and agree to the form online; instead of handing participants a gift card, give them a code that lets them spend their incentive online right away or let them know that you will mail them a gift card immediately.

Table 7.2

A quick guide to what you need to do during each type of user research activity

| Diary study | Interview | Survey | Card sort | Focus group | Field studies | Evaluation | |

| Invite observers | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Welcome participants | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Moderate the activity | No | Yes | No | Maybe | Yes | Maybe | Maybe |

| Record and notetake | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Deal with late and absent participants | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Inviting Observers

By the term “observer,” we mean someone who does not have an active role during the activity. For example, you may want to invite a developer who has a difficult time understanding that users approach an interaction differently than she does. Strive to invite stakeholders to view live user research sessions in a way where their presence will not distract, disrupt, and/or intimidate participants (e.g., behind a one-way mirror, sitting quietly in the back of a room, via a webcam). When it is not possible or practical to invite observers to view a live session (e.g., diary studies), be sure to collect data in a way that will allow stakeholders to hear the participants’ voice and understand their perspective. To learn about setting up a way for observers to view user research sessions, see Chapter 4 on page 82.

In addition to helping observers understand user needs, another advantage of inviting observers is team building. You are all part of a “team,” so stakeholders should be present at the activities, too. Also, it helps stakeholders understand what you do and what value you bring to the team—and that builds credibility. It is also wise to record sessions and make these recordings available for any stakeholders who may not be able to attend, as well as for your own future reference.

When you invite observers to a live session, it is a good idea to set expectations up front:

■ Tell the observers to arrive early and enter in a manner that is respectful and unobtrusive.

■ If observers are in a room near the participant, they may need to be quiet and still. Often, rooms divided by a one-way mirror might not be fully soundproof or not dark enough to hide all movements. When using a video link, this may not be a requirement.

■ Observers should turn off their cell phones. Answering calls will disturb participants and other observers. It can be difficult to get busy people (especially executives) to turn off their phones, but if they understand that their phone can interfere with the comfort of participants, colleagues, and equipment, they will usually oblige.

When you invite observers to a remote session:

■ Instruct observers to remain quiet during the session and remind them to turn off their cell phone ringers and for those using video or audio conference software, to mute their microphones and phones.

■ Always introduce everyone in the room, even if the participant cannot see everyone (e.g., in an audio-only interview or a video chat where you are the only person visible). If you do not introduce everyone in the room and someone speaks up (e.g., a designer, product manager or engineer pipes up to answer a participant’s question), you will have lost the participant’s trust.

Who Should NOT Observe?

In general, do not allow anyone who is in a supervisory or managerial role over a specific participant to observe that participant. If participants believe that their boss is watching, it can dramatically impact what they do or say. For example, in a field study, if participants know their boss is watching them, they may say that they do things according to what the company policy dictates rather than how they perform in practice. Explain to managers or supervisors that their presence may intimidate the participant and that you will summarize the data for them (without specific participant names). We find that with this explanation, they typically understand and accept your request not to observe. If you are unable to avoid this situation for political reasons (e.g., a high-profile customer insists on observing), you may have to allow the supervisor to observe and then scrap the data. For ethical reasons, let the participant know he or she will be observed by the supervisor before you start the session.

Welcoming Your Participants

Welcoming Participants to a Lab Session

If participants are meeting you at a lab or other similar location, ask them to arrive about 15 minutes before the session is due to begin (30 minutes if you are serving a meal). This allows enough time for participants to get some food, relax, and chat. In the case of a group session, it also provides a buffer in case some participants are running late. We tell participants during recruitment (refer to Chapter 6, “Recruitment Methods” section, page 139): “The session starts at 6:00 pm; please arrive 30 minutes ahead of time in order to eat and to take care of administrative details before the session starts. Late participants will not be admitted into the session.” Playing music during this time can provide a casual atmosphere and is more pleasant than the sound of uncomfortable silence or of forks scraping plates.

If it is a group session, during this presession period, post a colleague in the lobby with a “Welcome” sign on a flip chart to greet and direct participants as they arrive. Such a sign might read “Welcome participants of the TravelMyWay App focus group. Please take a seat and we will be with you shortly.” This sign lets participants know they are in the right place and directs them in case the greeter is not present. If your location has a receptionist, to avoid confusion, provide the receptionist with your participant list and make sure the receptionist asks all participants to stay in a specified location. If your location does not have a receptionist, put up a large sign that specifies where participants should wait in case people arrive while others are being escorted to the activity location. It saves time and effort to bring participants to the session location in groups of four or five. To avoid making multiple trips back and forth, ask participants if they need to use the bathroom along the way. If possible, have a receptionist or greeter ask participants to show ID and sign a nondisclosure agreement (NDA) while they are waiting to meet you.

Welcoming Participants in the Field

If you are meeting participants in the field (e.g., their home or office), you should also arrive early so participants are not waiting for you! If you are visiting a participant at his or her home, arrive in the area early, but do not go to his or her door until right on time. He or she may have arranged his or her day around you, so do not expect him or her to be available before the appointment time.

Introducing the Session

Once your participant or participants have arrived, or you have arrived in the field, you should welcome them, introduce yourself, give them an overview of the session, tell them the overall goals, let them know about any observers who will be watching the session and have them sign the NDA and consent form. You should also outline any ground rules you have for the session and set up expectations. For example, ask participants to turn off their cell phones.

Consenting Participants

Once you are sure participants understand the plan for the session and their part in it, you are ready to begin the consent process. Remember that the consent process involves more than just having participants sign a form. Instead, it is a conversation between you and the participants that results in the participants understanding the goals of the session and plan for the session and their willingness and knowledgeable agreement to participate. Once you are sure the participants know the plan, are comfortable with the plan, and want to participate, have them sign two copies of the NDA and consent form—one for you and one for them. This is also a good time to revisit the NDA, if they signed it in advance, and to make sure participants understand that they are agreeing to keep any information about the session confidential.

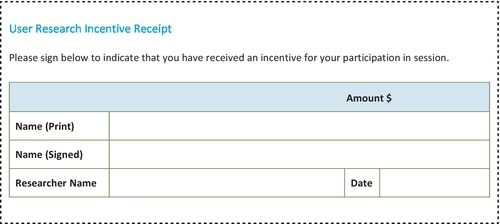

Providing Incentives

We recommend providing the incentives you agreed to provide (see Chapter 6, “Incentives” section, page 118) as part of your consent process. That way, participants are more likely to believe you when you tell them that they are free to leave at any time without penalty. It is a good idea to ask participants to sign a simple receipt acknowledging they have received the incentive (see Figure 7.1).

Developing Rapport

When conducting any kind of user activity, ensure that your participants are comfortable and feeling at ease before you begin collecting data that you will use. When conducting an individual activity, start out with some light conversation. Comment on the weather; ask whether the person had any trouble with traffic or parking. Be sure to carve out a bit of time, even if it eats into your hour, to make the participant comfortable. Keep it casual. When you sit down to begin the session, start with an informal introduction of yourself and what you do. Ask the participant to do the same. Also, find out what you should call the person, and then, use first names if appropriate.

Warm-Up Exercises

Ensuring that participants are at ease is extremely important for group activities. Each person will typically need to interact with you and everyone else in the room, so you want to make sure they feel comfortable. In addition to developing rapport with participants, you may also want to conduct some warm-up exercises. One method we use is to give people colorful markers and name tags or name tents and ask them to write their names and draw something that describes their personality. For example, if I like to ride horses, I might draw a saddle on my name tag. During this time, the moderators should also create name tags for themselves.

Once everyone has finished, we ask the participants to describe their drawing for the group. The moderators should go first and explain what they have drawn on their own name tags and why. This will help to put the first participant at ease when he or she describes his or her name tag and so on around the room. Any type of warm-up activity that gets people talking will do.

The name tag activity is great because it serves a twofold purpose: it helps everyone relax, and it helps you get exposure to each person’s name. You should use people’s names as much as possible throughout the session to make the session more personal.

You can use any kind of warm-up activity that you feel works best for you. Your goal should be to get everyone talking and to get those creative juices flowing. Fifteen minutes should be plenty of time to accomplish this. Here are a few example warm-up exercises we have used in the past:

■ In a group setting, ask people to introduce themselves and say one interesting thing about themselves.

■ Ask people what they like and dislike about the current product they are using.

■ Ask general, easy-to-answer questions about the topic that is the focus of the study. For example, if you are studying the TravelMyWay mobile app, you might ask participants, “What are your three favorite mobile phone apps? Why?”

Moderating Your Activity

Excellent moderation is key to the success of any activity. The moderator is responsible for setting expectations, keeping track of time, maintaining control over the session, and providing motivation. Even when participants are provided with instructions, they do not always know exactly what you are looking for, so it is your job to remind and guide them. Also, since many times these activities are scheduled in the evening and people are tired after work, it will be your job to keep them energized. A moderator must keep the participants focused, keep things moving, make sure everyone participates equally, and ultimately ensure that meaningful data are collected.

Moderation of a group is more complex, but moderation is also important for individual activities. There are a few rules that apply to both types, such as staying focused and keeping the activity moving. Some common individual and group moderating scenarios are discussed below. Table 7.3 provides some suggested statements in response to different moderation situations.

Table 7.3

Moderation tips: what to say when you want to …

| Set expectations | “If you ask me questions, I may not really answer you or I may be vague. If I’m doing that, I’m not being unfriendly; I’m just trying to stay neutral.” |

| Turn a question around | “I’m not sure, but tell me more about what you’re thinking here …” “What matters is your experience, which we can learn from. Tell me more about what you’re experiencing here …” |

| Prompt a silent/nonresponsive participant | “What are you trying to do right now?” “What are you thinking right now?” “What is going through your mind right now?” |

| Provide reassurance and build engagement | “There are no wrong answers here; you’re here to help us.” “If we didn’t see what areas work well or not so well for you, we wouldn’t learn anything.” “Please know that your candor is appreciated. Nothing you say will hurt anyone’s feelings. You’re here to help us make the product better for yourself and future users.” “This is just the kind of feedback we want to hear …” |

| Redirect or cut feedback short | “This is all very helpful to see and hear. Just for the sake of time, I’m going to ask you to go to the next task/go back to …” “Let’s move on for now. I wanted to ask you about what you did earlier …” “Let’s stop this here and we can come back to it later. Read the next scenario …” “I’m interested in hearing more about this. I do want to make sure we cover everything we have planned, so if there is time, let’s come back to this at the end of the session …” |

| End a session early | “You went through everything faster than expected, so we’re going to get you out of here early.” “That’s actually all I had for you today, so you’ll get some time back in your day! Thank you so much for your feedback.” |

Source: Adapted from Tedesco & Tranquada (2014) Appendix A: What to Say. The Moderator’s Survival Guide.

Moderation Strategies

Be Approachable and Positive

Participants should feel at ease around you, the moderator. Be personable and approachable; remember to smile and look them in the eyes. You may be tired and have had a terrible day, but you cannot let it show. You need to emanate a positive attitude. Before the session begins, chat with participants. You do not need to talk about the activity, but participants often have questions about your job, the product, or the activity. Getting to know the participants will help you get a sense for the type of people, and it will put them at ease and get them comfortable speaking to you.

Ask Questions

Remember that you are not the expert in the session. The participants are the experts, and you should make them aware of that. Let them know that you will be stopping to ask questions and get clarification from time to time. The participants will undoubtedly use acronyms and terminology with which you are unfamiliar, so you should stop them and ask for an explanation rather than pushing on. There is no point collecting data that you do not understand.

You also want to make sure that you capture what the user is really saying. Sometimes, the best way to ensure that you understand someone is to listen reflectively (“active listening”). This involves paraphrasing what the participant has said in a nonjudgmental, nonevaluative way and then giving the participant a chance to correct you if necessary.

At other times, you will need to probe deeper and ask follow-up questions. For example, Vivian may say, “I would never research travel on my phone.” If you probe further and ask “Can you explain that a little more?” you may find out that it is not because Vivian thinks it would be a bad idea to research travel on her phone; it is just that she never conducts travel research because she spends all of her vacation time at her condo in the Florida Keys.

Stay Focused

Do not let participants go off on a tangent. Remember that you have a limited amount of time to collect all of the information you need, so make sure that participants stay focused on the topic at hand. Small diversions, if relevant, are appropriate, but try to get back on track quickly. A good strategy for getting participants back on track is to say something like “That is really interesting. Perhaps we can delve into that more at the end of the session, if we have time.”

Another strategy is to visually post information that will help keep people on track. For example, if you are running a focus group, write the question on a whiteboard. If people get off topic, literally point back to the whiteboard and let them know that although their comments are valuable, they are beyond the scope of the session. You can also periodically repeat the question to remind people what the focus of the discussion is.

Keep the Activity Moving

Even when people stay focused on the goal or question presented in the activity, they sometimes go into far more detail than necessary. You need to control this; otherwise, you might never finish the activity. It is OK to say “I think I now have a good sense of this topic, so let’s move on to the next topic because we have a lot of material to get through today.” After making a statement such as this once or twice during the session, people will typically get a sense of the level of detail you are going after. You can also let them know this up front in your introduction, by saying, “We have a lot to cover today, so I may move along to the next topic in the interests of time.”

You Are Not a Participant

It is critical that you elicit thoughts and opinions from participants without interjecting your own thoughts and opinions about the topic. Be patient and let participants answer the questions; do not try to answer for them. Also, do not offer your opinions because that could bias their responses. This may sound obvious, but sometimes, the temptation can be very hard to resist. It may be particularly difficult in an interview session when participants ask you for your opinion about a product or ask for your help with a task. A good response to use in this case is “You’re the expert here. I’m interested in hearing about what you think.” If you fall into the trap of inserting your opinion, you will end up with results that represent your thinking instead of that of the users.

Keep the Participants Motivated and Encouraged

User research activities can take anywhere from five minutes to months to complete. On average, an in-person, moderated user research activity lasts one to two hours. This is quite a long period of time for a person or a group of people to be focused on a single activity. You must keep people engaged and interested. Provide words of encouragement as often as possible. Let them know what a great job they are doing and how much their input is going to help your product or understanding of a topic. A little acknowledgment goes a long way! Also, keep an eye on your participants’ energy levels. If they seem to be fading, you might want to offer them a break or offer up some of those leftover cookies or coffee to help give them the necessary energy boost. You want everyone to have a good time and to leave the activity viewing it as a positive experience. Try to be relaxed, smile often, and have a good time. Your mood will be contagious.

No Critiquing

As the moderator, you should never challenge what participants have to say. This is crucial, since you are there to learn what they think. You may completely disagree with their thoughts, but you are conducting user research and you are not the user in this situation. You may want to probe further to find out why a participant feels a certain way, but at the end of the day, remember that, in this session, he or she is the expert, not you. We often include a statement like this at the beginning of a session:

Remember, there are no right or wrong answers here. We are not evaluating you. All ideas are correct, and we welcome all your thoughts and comments.

Practice Makes Perfect

Moderating activities is not easy and requires practice. We still find that we learn new tricks and tips and also face new challenges with each session. We recommend that people new to moderating groups watch videos of the activity they will be conducting and observe how the facilitator interacts with the participants. Next, they should shadow a facilitator. Being in the room as the activity is going on is a much richer experience than watching a video. Also, a beginner should practice with colleagues who are experienced moderators. Set up a pilot session so you can practice your moderating skills before the real activity. Have your colleagues role-play. For example, one person can be the dominant participant, one can be the quiet participant, and one can be the participant who does not follow instructions. You can record the sessions and watch them with an experienced moderator to find out how you can improve. Another great idea is to be a participant in user research activities. Find a local facility that runs and/or recruits for them and contact them to get on their participant list. That way, you can observe professional moderators at work. Finally, be sure to practice answering questions that are likely to come up while you are moderating a study. For example, when moderating a study on software, users would frequently ask if a certain feature was enabled. Instead of saying yes or no, we would say, “This is the out-of-box product,” which was enough information for them to be happy, but did not give any more details than necessary.

Find Your Own Style

There is no one moderation style that works for everyone. For example, some people can easily joke with participants and use humor to control the overbearing ones: “If you don’t play well with the others, I will have to take your pen away!” Other people are not as comfortable speaking in front of groups and have difficulty using humor in these situations. In those cases, trying to use humor can backfire and might come across as sarcasm. Find an experienced moderator to emulate—one whose personality and interaction style is similar to yours.

Using a Think-Aloud Protocol

A think-aloud protocol is the process of having participants speak what they are thinking as they complete a task. This technique not only is typically used for usability tests but also can be quite beneficial for certain user research activities where you are working with one person at a time—for example, individual card sorts (refer to Chapter 10, page 266) and field studies (refer to Chapter 13, page 380).

Using a think-aloud protocol, you get an understanding of why the user is taking the actions that he or she takes and the person’s reactions to and thoughts about what he or she is working with. For example, in the case of a card sort, you can learn about why the person groups certain cards.

Before asking participants to think aloud, it is helpful to provide an example, preferably one that reflects what they will be working with. If they will be completing tasks on a mobile phone, for example, demonstrate an example with a phone-based task. Remember that the instructions to the participant should model what you want them to do. So if you want them to describe expectations, model that for them. If you want them to express feelings, model that for them. During the demonstration, the facilitator works through the task and the participant observes him or her using the protocol. Below is an example of a think-aloud protocol demonstration using a mobile phone to send an SMS text (adapted from Dumas and Redish, 1999):

As you participate today, I would like you to do what we call “think out loud.” What that means is that I want you to say out loud what you are thinking as you work. Let me show you what I mean. I am going to think out loud as I try to send a text message on this mobile phone. OK, I am looking at the home screen of the phone. I would expect there to be an icon that says “text” or “messages” right here on the home screen, but I don’t see that here. I’m confused by that. I’m going to look in other places for it. I think I’ll try to click on this icon of a callout bubble because that seems like it might be related to talking, like “I talk, the other person talks.” Okay, now that that is open, I see an icon that says “text messages.” I’m glad to see that there because that is what I was expecting to see.

Do you see what I mean about thinking out loud? Now let’s have you practice by telling me out loud how you would send an e-mail on this phone.

It may help participants to describe to them that you want to hear what they are thinking as they interact with a product rather than their opinion about a product. For example, while you do want to know what they are trying to accomplish, what they are looking at, and what they expected, you are not interested in other things they may want to tell you, for example, how they think other people will feel about an interface. When participants understand what you are looking for and say things like, “I am looking for a way to book an airline ticket using this mobile app, but I was expecting it to be in the ‘purchase’ tab,” give them positive feedback in the form of an “mm hmm.” If they get off track and say something like “I don’t think most people will think this color green is attractive. You should change it,” redirect them to the task, and ask, “Tell me what you expected to see here.”

If you are recording the session, you may find that participants need to be reminded to speak up. Many participants talk quietly as if it were a private conversation instead of a recorded session. If they are quiet, we say, “That was just what I want you to do, but remember you are speaking to the microphone, not just to me. You may have to talk a bit louder. Don’t worry; I will remind you if I can’t hear you.”

Think-aloud protocols are not without their limitations. For example, people are limited in what they themselves can understand and convey about their own thought processes and motivations (Boren & Ramey, 2000; Nisbett & Wilson, 1977). In addition, having people participate in a think-aloud protocol takes resources away from the task they are performing, thus reducing the cognitive capacity people will have to devote to the task itself. Despite these limitations, think-aloud protocols are often a very useful technique.

Debrief Participants

At the conclusion of the study, you should thank participants, give them a chance to ask any questions they may have, tell them about the goals of the study, and provide any incentive you have agreed to provide, if you have not already provided this during the consent process (see Chapter 6, “Incentives” section, page 118).

Recording and Notetaking

There are a few options when deciding how to capture information during your activity.

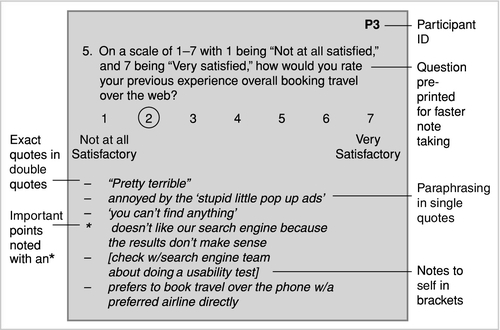

Take Notes

Taking notes on a laptop and taking notes by hand on paper are two obvious options. One of the benefits of taking notes during the session is that you can walk away from the activity with immediate data and begin analysis (see Figure 7.2 for sample notes from an interview). You are also signaling to the participants that you are noting what is being said. It is good to show the participants that you are engaged in the activity, but they might be offended if you are not taking notes when the participants feel they are saying something particularly noteworthy. When taking notes on a laptop, there is also the possibility that participants may think you are doing something else on the laptop, like checking your e-mail, rather than paying attention to them. If you are a touch typist, you can avoid this by looking at the participants, rather than your screen while you take notes on a laptop.

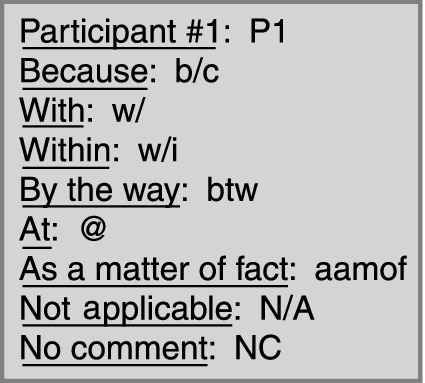

A potential problem with taking notes is that you can get so wrapped up in being a stenographer that you have difficulty engaging the participants or following up. You could also fail to capture important comments because the pace of a discussion can be faster than your notetaking speed. If you choose to take notes yourself during a session, develop shorthand so that you can note key elements quickly (see Figure 7.3 for some sample shorthand). Also, do not try to capture every comment verbatim—paraphrasing is faster and sufficient for most purposes. If you need verbatim quotes, consider using video or audio recording.

For some activities, such as focus groups, the moderating is so consuming that it is simply not possible for you to take effective notes. In that case, a better option is to have a colleague take notes for you.

A notetaker can be in the same room with you, watching a live video stream, or watching from behind the one-way mirror if you have a formal lab setup (refer to Chapter 4, “Building a Permanent Facility” section, page 85). It can also help to have an additional pair of eyes to discuss the data with and come up with insights that you might not have had yourself.

If the notetaker is in the same room, you may or may not want to allow the person to pause the session if they get behind in the notes or are not understanding what a participant says. This can be very disrupting to the session, so ideally, you want an experienced notetaker who will not require this. The person should not attempt to play court stenographer: you are not looking for a word-by-word account, only the key points or quotes. The moderator should keep the notetaker in mind and ask participants to speak more clearly or slowly if the pace becomes too fast.

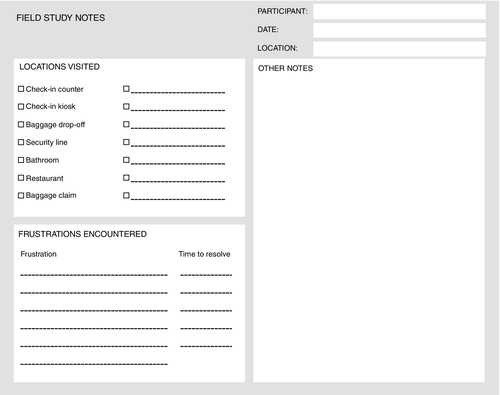

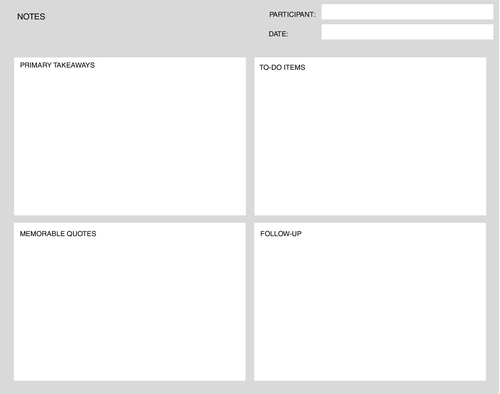

Another way to facilitate notetaking is to prepare a notetaking template in advance of the research activity. If you have specific ideas about what you are looking for, you can include placeholders in the template that serve both to remind you to note comments and/or behaviors relevant to a particular topic and to organize your notes so it is easier to find this information for analysis. For example, Figure 7.4 shows a template for notes for a field study of mobile app users at an airport. If you do not know in advance what you are looking for (i.e., in more exploratory work), then you can use a template that is more generic (see Figure 7.5).

Finally, it is also helpful when you can get any of the stakeholders viewing the activity to take notes. This can add further richness to the data you collect and helps more people feel like they are actively contributing and therefore invested in the results.

Use Video or Audio Recording

The benefits of recording are numerous. First, if you are moderating solo and do not have a notetaker, you can focus solely on following up on what the participants say and use your energy to motivate them and understand what they are telling you instead of taking notes. The recordings also capture nuances in speech and context that you may not capture when taking notes (e.g., the participant’s instant message window kept popping up causing the participant to pause his or her speech). Video recording also has the benefit of showing you the participant’s (as well as your own) body language. You can also refer back to the recordings as often as needed and, in some cases, analyze these data directly.

If you choose to rely solely on video or audio recording and not to take notes during the session, you must either listen to the recording and make notes or send the recording out for transcription. Transcription can be very expensive and can take a long time to complete. Depending on the complexity of the material, the number of speakers, and the quality of the recording, it can take four to six times the duration of the recording to transcribe (e.g., a one-hour interview can take four to six hours to transcribe). There are many online services that offer transcription services. In 2014, we found prices ranging from $1 to $3 per minute of audio, meaning that the cost to transcribe a single two-hour interview can run between $120 and $360.

We recommend getting transcripts of the session only when you need a record of who said what (e.g., for exact quotes or documentation purposes) or for scientific research where this level of detail is required (e.g., for a content analysis, you need verbatim participant quotes). Regulated industries (e.g., Food and Drug Administration) may also require such documentation.

Finally, you should be aware that recording the session can make some participants uncomfortable, so they may be less forthcoming. Let the participants know when you recruit them that you plan to record. If a person feels uncomfortable, stress his or her rights, including the right to confidentiality. If the person still does not feel comfortable, then you should consider recruiting someone else or just relying on taking notes. In our experience, this outcome is the exception rather than the rule.

Finally, it is a good idea to have a policy about how long you plan to keep video files. Will you keep them only until you have presented recommendations to stakeholders and then delete them? Will you keep them for a one-year period no matter the status of the study at that point? If you work in academia, if your study receives funding from some agencies (e.g., National Science Foundation), or is approved by an IRB, you may be required to keep the recordings for a specified period. Refer to Chapter 3, “Data Retention, Documentation, and Security” section on page 75 for more information.

Use Screen-Recording Software

When your activity involves having users interact with an artifact such as a website or mobile app, it is often desirable—some would say essential—to record not only what the participant is doing but also what is happening on screen. There are many screen-recording tools (both commercial and open-source) available for use during in-person and remote sessions, such as the following:

■ Adobe ConnectNow (www.adobe.com)

■ CamStudio (camstudio.org)

■ GoToMeeting (www.gotomeeting.com)

■ Morae (www.techsmith.com/morae.html)

■ Skype (www.skype.com)

Be sure to try out your screen-recording software in advance of your study. Sometimes, this software will interfere with the performance of the interface you are testing, especially when the software is in a prototype state.

Combine Video/Audio/Screen Recording and Notetaking

As with most things, a combination is usually the best solution. Having a colleague take notes for you during the session while it is being recorded is the optimal solution. That way, you will have the bulk of the findings in notes, but if you need clarification on any of the notes or user quotes, you can refer back to the recording. This is often necessary for group activities because so many people are speaking and because conversations can move quickly. An audio or video recording of the session will allow you to go back and get clarification in areas where the notes may not be clear or where the notetaker may have fallen behind. In addition, although it is rare, recordings do fail, and your notes are an essential backup.

Dealing with Late and Absent Participants

You are sure to encounter participants who are late or those who simply do not show up. In this section, we discuss how to prevent or deal with these situations.

The Late Participant

You are certain to encounter late participants in both group and individual activities. While many of these issues do not apply to remote activities, other issues, such as technical issues that delay the start of remote sessions, do arise. We do our best to emphasize to participants during the recruiting phase that being on time is critical—and if they are late, they may not be able to participate in the session. We emphasize this again when we send them e-mail confirmations of the activity and when we call to remind them about the session the night before. It is also a good idea to make them aware of any traffic, parking, or setup issues that may require extra time and provide them with parking passes via mail and instructions for setting up their computer to use remote software in advance, if needed. Or, if you are on-site, be sure they are clear about where you will be located if you are not going to them.

However, through unforeseen traffic problems, getting lost, and other priorities in peoples’ lives, you will often have a participant who arrives late despite your best efforts. Thanks to cell phones, many late participants will call, text, or e-mail you to let you know they are on their way or are still getting their computer up and running. If it is a group activity and you have some extra time, you can try to stall while you wait for the person to show up. If it is an individual activity, your ability to involve a late participant may depend on the flexibility of your day’s schedule. We typically schedule a one-hour cushion between participants, so a late participant presents less of a problem. For group sessions, we will typically build in a 15-minute cushion knowing that some people will arrive late. It is not fair to make everyone wait too long just because one or two people are late. If it is an evening session and we are providing food, we ask participants to arrive 30 minutes earlier than the intended session time to eat. This means that if people arrive late, it will not interfere with your activity. They will just have less time (or no time) to eat.

You Cannot Wait Any Longer

In the case of a group activity, at some point, you will need to begin your session whether or not all of your participants are present. The reality is that some participants never show, so you do not want to waste your time waiting for someone who is not going to appear.

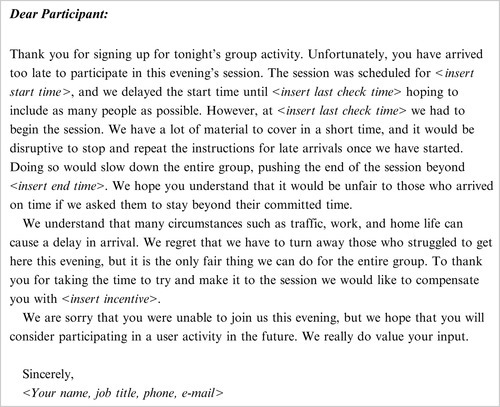

After 15 minutes, if a participant does not appear, leave a “late letter” (see Figure 7.6) in the lobby with the security guard or receptionist. For companies that do not have someone employed to monitor the lobby on a full-time basis, you may wish to arrange ahead of time to have a colleague volunteer to wait in the lobby for 30 minutes or so for any late participants. Alternatively, you can leave a sign (like the “Welcome” sign) that says something like, “Participants for the TravelMyWay App Focus Group: the session began at 5 pm and we are sorry that you were unable to arrive in time. Because this is a group activity, we had to begin the session. We appreciate your time and regret your absence.”

You should provide an incentive in accordance with the policy you stated during recruitment. If you do not plan to pay participants if they are more than 15 minutes late, you should inform them of this during recruitment. However, you may wish to offer a nominal incentive or the full incentive to participants who are late as a result of bad weather, bad traffic, or other unforeseeable circumstances. Just decide prior to the activity, inform participants during recruiting, and remain consistent in the application of that policy. Make sure you tell whomever is waiting to greet the late participants to ask for identification before providing the incentive (refer to Chapter 6, “The Professional Participant” section, page 151) and have the participant sign a receipt (see Figure 7.1).

As an added courtesy, you may wish to leave the late participant a voice mail on their cell phone and home or work phone. State the current time and politely indicate that because the person is late, he or she cannot be admitted to the session. Leave your contact information and state that the person can receive an incentive (if appropriate) by coming back to your facility at his or her convenience and showing a driver’s license (if ID is one of your requirements) and/or reschedule for another time.

Including a Late Participant

There are some situations where you are unable to turn away a late participant. These situations may include a very important customer who you do not want to upset or a user profile that is very difficult to recruit and you need every participant you can get.

Again, for individual sessions (e.g., interviews), we typically have about an hour cushion between participants so a latecomer is not that big a deal. For group sessions, it is a little more difficult to include latecomers. If they arrive just after the instructions have been given, you (or a colleague) can pull them aside and get them up to speed quickly. This is by no means ideal, but it can usually be done fairly easily and quickly.

If the participant arrives, the instructions have been given, and the activity itself is well under way, you can include him or her, but you may have to discard his or her data. Obviously, if you know you are going to throw away the person’s data, you would only want to do this in cases where it is politically necessary to include the participant, not for cases where the participant is hard to get. In cases where participants are hard to come by, make sure you reschedule the participant(s). Keep in mind that if you reschedule them, the participants who are late once are more likely to be late again or be no-shows.

The No-Show

Despite all of your efforts, you will encounter no-shows. These are the people who simply do not show up for your activity without any warning. We have found that for every 10 participants, one or two will not show up. This may be because something important came up and you are the lowest priority or the person may have just completely forgotten. Chapter 6 discusses a number of measures that you can take to deal with this problem, for example, calling participants the night before the study (refer to Chapter 6, “Preventing No-Shows” section, page 146).

Dealing with Awkward Situations

Just when you think you have seen it all, a participant behaves in a way you could never have expected! The best way to handle an awkward situation is by preventing it all together. However, even the best-laid plans can fail. What do you do when a user throws you a curve ball? If you are standing in front of a group of 12 users and there is a room of eight stakeholders watching you intently, you may not make the most rational decision. You must decide before the situation ever takes place how you should behave to protect the user, your company, and your data. Refer to Chapter 3, Legal and Ethical Considerations on page 66 to gain an understanding of these issues.

In this section, we look at a series of several uncomfortable situations and suggest how to respond in a way that is ethical and legal and that preserves the integrity of your data. Unfortunately, over the last several years, we have encountered every single one of these awkward situations. They have been divided by the source of the issue (i.e., participant or product team/observer). We invite you to learn from our painful experiences.

Participant Issues

The Participant Brings Company

Situation: A participant shows up in the lobby escorted by friends or family (e.g., an elderly woman shows up with her son, who wanted to make sure she was not being scammed, a child is driven to the location by his or her parent). When you greet the participant, she says, “This is my son. He drove me here. Can he join us?”

Response: If the participant is an adult, politely say, “We prefer for guests to wait in the lobby.” If this distresses the participant, then you may want to allow it. If you do, make sure the guest signs an NDA and ask the guest to sit quietly in the back of the room so as not to influence the participant or interrupt the session. In the case of a child who has her parent with her, common sense and law require that the parent be allowed to be in the same room as his or her children, if he or she requests it. Just as for other guests, make sure the parent signs an NDA and knows to sit quietly so as not to influence the child’s performance.

The Participant’s Cell Phone Rings Continuously

Situation: The participant is a very busy person (e.g., doctor, database administrator). She is on call today and cannot turn off her cell phone for fear of losing her job. Throughout the session, her phone vibrates, interrupting the activity. Each call lasts only a couple of minutes, but it is clear that the participant is distracted. This user type is really hard to come by so you hate to lose her data. Should you allow the activity to continue, or ask her to leave?

Response: It is obvious that the user is distracted, and it will not get better as the session continues. If this is an individual activity, you may choose to be patient and continue. However, if this is a group session where the user is clearly disturbing others, have a collaborator follow the participant out during the next call. When she finishes her call, ask her to turn the phone off because it is causing too much distraction. If this is not possible, offer to allow her to leave now and be paid.

You should inform potential participants during the screening process that they will have to turn their cell phones off for the duration of the activity (refer to Chapter 6, “Developing a Recruiting Screener” section, page 129). If the potential participant will be on duty the day of the session and cannot comply with the request, do not recruit him or her. When the participants arrive for the activity, ask everyone to turn their cell phones off. They agreed to give you one or two hours of their time and you are compensating them for it. It is not unreasonable to insist they give you their full attention, especially if you made this request clear during the screening process.

The Wrong Participant Is Recruited

Situation: During an activity, it becomes painfully obvious that he does not match the user profile. The participant has significantly less experience than he originally indicated or does not match the domain of interest (e.g., has the wrong job to know about anything being discussed). It is not clear whether he was intentionally deceitful about his qualifications or misunderstood the research in the initial phone screener. Should you continue with the activity?

Response: Is the participant different on a key characteristic? If you and the team agree that the participant is close enough to the user profile to keep, continue with the activity and note the difference in the report.

If the participant is too different, your response depends on the activity. If it is a group activity where the participants do not interact with one another (e.g., a group card sort), note the participant and be sure to throw his data out. If it is a group activity that involves interaction among the participants, you will have to remove the participant from the session because the different user type could derail your session entirely. Take the participant aside (you do not want to embarrass him in front of the group) and explain that there has been a mistake and apologize for any inconvenience you may have caused. Be sure to pay the participant in full for his effort.

If it is an individual activity, you may wish to allow the participant to continue with the activity to save face and then terminate the session early. It may be necessary to stop the activity on the spot if it is clear that the participant simply does not have the knowledge to participate and to continue the activity would only embarrass the participant further. Again, pay the participant in full; he or she should not be penalized for a recruiting error.

The Participant Gets Extremely Frustrated

Situation: During the study, the participant becomes extremely frustrated because he or she cannot answer your questions or cannot complete a task you have asked him or her to do. He or she begins verbally beating him or herself up about his or her inability to “do anything right.” Should you stop the session immediately and dismiss him or her?

Response: First, do not blame yourself. Participants bring their own frustrations to the session and these are not your fault. If the participant’s frustration is clearly something that does not have to do with the session, you may want to end the session early. If the participant’s qualifications are the issue, see above. Either way, you may want to offer the participant a different set of questions or tasks—that is, he or she will be easily able to answer or complete—before you wrap up the session so that he or she leaves feeling good, rather than helpless.

The Participant Notices Technical Issues

Situation: You introduce a prototype during the study that is supposed to be working well enough to be evaluated. However, the prototype crashes in the middle of the session and you cannot get it restarted. The participant obviously notices the technical issues and does not know how to react.

Response: Remember that you, as the moderator, should set expectations. Immediately reassure the participant that he or she did not do anything wrong and tell him or her what will happen next. If you feel certain that you or a colleague will be unable to get the prototype working again within the time for the session, you have a couple options. If you have a lower-fidelity prototype, such as a paper prototype, you may revert to that. Alternatively, you may want to turn the session into an impromptu interview if you think the participant could provide useful input. Finally, you may simply end the session early. Pay the participant the full amount; it is not his or her fault the technology failed.

The Participant Has a Conflict of Interest

Situation: When you greet a participant at her home for a field study, you see her name badge hanging on the key holder by the front door. You recognize the name of the company as a competitor. Should you conduct the session anyway?

Response: If the participant turns out to work for a competitor, is a consultant who has worked for a competitor and is likely to return to that competitor, or is a member of the press, you need to terminate the session immediately. Remind the person of the binding confidentiality agreement and pay her. Put her on the watch list immediately (refer to Chapter 6, “Create a Watch List” section, page 151).

Follow up with the recruiter to find out why this participant was recruited (refer to Chapter 6, “Recruitment Methods” section, page 139). Review the remaining participant profiles with the team/recruiting agency to make sure that no more surprises slip in. If the project is particularly sensitive, you may need to review and approve each user with the team as he or she is recruited.

The Participant Thinks He Is on a Job Interview

Situation: The participant arrives in a suit and brings his résumé, thinking he is being interviewed for employment at your company. He is very nervous and asks about available jobs. He says that he would like to come back on a regular basis to help your company evaluate its products. He even makes reference to the fact that he needs the money and is grateful for this opportunity to show his skills.

Response: This situation can be avoided by clarifying up front when the participant is recruited that this is not a job interview opportunity and in no way constitutes an offer of employment (refer to Chapter 6, “Developing a Recruiting Screener” section, page 129). If the participant attempts to provide a résumé at any point in the conversation, stop the activity and make it clear that you cannot and will not accept it. If you do accept it, you may further the participant’s confusion about the session and receive follow-up phone calls or e-mails from the participant “to touch base about any job opportunities.”

If you have already started the activity when you discover that the participant believes he is on a job interview, you need to be careful not to take advantage of a person who is obviously highly motivated but for the wrong reasons. In this case, the activity should be paused and you should apologize for any misunderstanding and make it clear that this is not a job interview. Reiterate the purpose of the activity and clarify that there is no follow-up opportunity for getting a job at your company that can be derived from his participation. The participant should be asked whether he would like to continue now that the situation has been clarified. If not, the participant should be paid and leave with no further data collection.

The Participant Gets Lost Trying to Find the Study Location

Situation: You have reserved a study location that has special features that you need to provide context to the issue you are studying. You only have this space for a limited time, so you are sure to provide excellent directions and a map to your study location. A participant is very late to his individual interview session at the location. You call the participant’s cell phone but do not get an answer. Just then, you hear a knock on the door. Instead of just your participant, you see two security guards with your participant. One security guard says, “We found this guy wandering around. He says he’s here to see a ‘magic’ house. Is he yours?” How do you respond to the security guards? Should you cancel the session with the participant? Should you use his data?

Response: Thank the security guards for escorting the participant to your location. Briefly explain to them that you expect more participants to be coming and you sincerely appreciate their help pointing any other lost participants to the location because you know it is very difficult to find. Let the participant hear you so he knows you understand how difficult it is to find the location and, by inference, that you understand that he did nothing wrong. Once the guards have gone, have the participant sit down and talk with him. How is he feeling? Is he stressed out because of the interaction with the guards? If so, offer to reschedule the session. If the participant refuses, offer the incentive right away and remind him that he does not need to continue with the session. If he still wants to participate in the study because he feels his ordeal would be wasted otherwise, do not refuse him this comfort. Go on with either the study as planned or a less stressful, shortened version. At the conclusion of the session, thank the participant for coming and participating, despite the difficulty finding the location. If the participant was obviously affected by the experience, you may need to discard the data. However, if the participant easily calmed down and you conducted the study as planned, you may be able to include it, as long as you check it against your other data and it seems to fit. To prevent this in the future, speak with participants on the phone and stress that the building is difficult to find (e.g., not on GPS) and that it is very important that they follow the directions you provide or they will get lost.

The Participant Refuses to Be Video Recorded

Situation: During recruiting and the pretest instructions, you inform the participant that the session will be video recorded. The participant is not happy with this. She insists that she does not want to be video recorded. You assure her that her information will be kept strictly confidential, but she is not satisfied. Offering to turn the video recording off is also not sufficient for the participant. She states that she cannot be sure that you are not still taping her and asks to leave. Should you continue to persuade her? Since she has not answered any of your questions, should you still pay her?

Response: Although this rarely occurs, you should not be surprised by it. It is unethical to coerce the participant to stay and be recorded in a way that makes her uncomfortable. However, you may want to ask if she would be willing to be audio recorded instead. This is not ideal but at least you can still capture her comments. Alternatively, if the user type is difficult to find and/or if you are dealing with a customer, you may wish to rely on notes and assure her you are not video or audio recording. If she still balks, tell her that you are sorry she does not wish to continue but that you understand her discomfort. You should still pay the participant. If you have a list of participants to avoid, add her name to this list (refer to Chapter 6, “Create a Watch List” section, page 151).

To avoid such a situation in the future, inform all participants during the phone screening that they will be audio- and/or videotaped and must sign a confidentiality agreement (refer to Chapter 6, “Developing a Recruiting Screener” section, page 129). Will this be a problem? If they say that it is, they should not be brought in for any activity.

The Participant Wants to Take Photos and Videos to Share His or Her Experience Online

Situation: You greet a participant in the lobby. Upon seeing you, she immediately pulls out her cell phone, snaps your photo, and says how excited she is about visiting your workplace and giving feedback about your products. Before you can get in a word, she says, “I love your products and can’t wait to share what I learn today with my followers!” You realize what she means is that she plans to post the photo she has just taken of you on social media. How should you react?

Response: Tell the participant politely to please stop taking photos, recording, and/or broadcasting. Once she has done this, explain to her that she will have to read and sign an NDA if she has not already and that this requires that she cannot share anything confidential that you show her or discuss with her. You should explain to her that she should not even share the questions or topic of the study because those can reveal unexpected insights. If your company has a designated place where photos are permitted (e.g., company sign, lobby), take the participant there at the conclusion of the study and offer to take her photo. Remind her that she may share this photo, but no other details about the study. It is up to you if you want to request that she delete the photo she snapped of you when you greeted her. Keep in mind that if you do not ask her to delete it, you will have no control over what the participant writes about it or who she shares it with.

The Participant Is Confrontational with Other Participants

Situation: While conducting a group session, one of the participants becomes more aggressive as time goes by. He moves from disagreeing with other participants to telling them their ideas are “ridiculous.” Your repeated references to the rule “Everyone is right—do not criticize yourself or others” is not helping. Unfortunately, the participant’s attitude is rubbing off on other group members, and they are now criticizing each other. Should you continue the session? How do you bring the session back on track? Should you remove the aggressive participant?

Response: Take a break at the earliest opportunity to give everyone a chance to cool off. Since you are the focus of most participants at this moment, you will need a colleague to assist you. Have the colleague quietly take the participant outside of the room and away from others to dismiss him. The colleague should tell the participant that he has provided a lot of valuable feedback, thank him for his time, and pay him. When you restart the session, if anyone notices the absence of the participant, simply tell the group that he had to leave early. It is never easy to ask a participant to leave, but it is important not only to salvage the rest of your data but also to protect the remaining participants in your session.

The Participant Is Not Truthful About Her Identity

Situation: You recognize a participant from another activity you conducted but the name does not sound familiar. You mention to her that she looks familiar and ask whether she has participated in another study at your company. She denies that she has ever been there before, but you are convinced she has. Should you proceed with the test or pursue it further?

Response: Unless you are conducting an anonymous study, ask every participant for an ID when you greet him or her. If a participant arrives without some form of ID, apologize for the inconvenience and state that you cannot release the incentives without identification. If it is possible, reschedule the activity and ask the participant to bring an ID next time.

When recruiting, you should inform participants that you will need to see an ID for tax purposes, as well as for security purposes (refer to Chapter 6, “Developing a Recruiting Screener” section, page 129). In the United States, the Internal Revenue Service requires that companies complete a 1099 form for any individual who receives more than $600 from you in a year. For this reason, you need to closely track whom you compensate throughout the year. During recruitment, you may say to participants:

In appreciation for your time and assistance, we are offering a $100 gift card. For tax purposes, we track the amount paid to participants, so we will be asking for an ID. We also require an ID when issuing a visitor’s badge. If you can simply bring your driver’s license with you, we will ask you to present it upon arrival.

Repeat this in the phone or e-mail confirmation you provide to participants. For participants being dishonest about their identity (in order to participate in multiple studies and make additional money), this will dissuade them from following through. For honest participants, it reminds them to bring their ID with them, as opposed to leaving it in the car or at home.

If the information provided does not match the information on the driver’s license, you will have to turn the participant away. Then, copy the information from the ID next to the “alternative” information provided by the participant. Place both identities on your watch list (refer to Chapter 6, “Create a Watch List” section, page 151).

The Participant Refuses to Sign NDA and Consent Form

Situation: You present the usual NDA and consent form to the user and explain what each form means. You also offer to provide copies of the forms for the participant’s records. The participant glances over the forms but does not feel comfortable with them, particularly the NDA. Without a lawyer, the participant refuses to sign these documents. You explain that the consent form is simply a letter stating the participant’s rights. The NDA, you state, is to protect the company since the information that may be revealed during the session has not yet been released to the public. Despite your explanations, the participant will not sign the NDA. Should you continue with the activity?

Response: Absolutely not. To protect yourself and your company, explain to the participant that without her signature, you cannot conduct the activity. Since the participant is free to withdraw at any point in time without penalty, you should still provide the incentive. Apologize for the inconvenience and escort her out. Be sure to place her on your watch list (refer to Chapter 6, “Create a Watch List” section, page 151).

Prevent this situation by informing participants during recruitment that they will be expected to sign a confidentiality agreement and consent form (refer to Chapter 6, “Developing a Recruiting Screener” section, page 129). Always e-mail participants a copy of the forms for them to review in advance. Some participants (particularly VPs and above) cannot sign NDAs. Their company may have a standard NDA that they are allowed to sign and bring with them. In that case, ask the participant to e-mail you a copy of his or her NDA and then forward it to your legal department for approval in advance.

If the legal department approves of his or her NDA, you may proceed. However, if a participant states during the phone interview that he or she cannot sign any NDA, thank the person for his or her time but state that the person is not eligible for participation.

The Participant Is Under the Influence

Situation: You greet a participant in the lobby. He seems very happy to be at the session, smiling continuously as you walk to the testing room and prepare for the activity. As you begin a task that requires the participant to interact with a laptop computer and think aloud, you notice that he is staring at the screen in an unusual way and seems transfixed. When you prompt him to say out loud what he is thinking, he responds, “The mouse trails you’ve added here are really cool!” However, there are no mouse trails in the user interface. You realize that the participant may be under the influence of alcohol or drugs. Should you confront the person about whether he is under the influence? Do you continue the session? If so, should you use the data?

Response: Unless you are specifically studying altered performance (e.g., a driving simulator where you want to understand the affects of drunk driving), you should end the session as soon as you recognize that a participant may be under the influence. Whatever you do, do not confront the participant about being under the influence. You may be incorrect, but more importantly, you do not want a confrontation. Be discreet and polite (“Wow, you finished that task very quickly. That took less time than we expected. Thank you for all of your feedback!”) and provide the incentive, if you have not already. Escort the participant back to the lobby, provide him with water, coffee, and/or snacks if possible, and encourage him to wait in the lobby if he is feeling “tired.” If you are concerned about his ability to get home safely, offer to call a cab. Discretely inform both the receptionist and security of the situation and ask them to keep an eye on the participant. Discard any data you have collected, as it is not representative of users who are not under the influence.

Product Team/Observer Issues

The Team Changes the Product Midstudy

Situation: You are conducting a focus group for a product that is in the initial prototype stage. The team is updating the code while the focus groups are being conducted. In the middle of the second focus group, you discover the team has incorporated some changes to the product based on comments from the previous focus group. Should you continue the focus groups with the updated product or cancel the current focus group and bring in replacements so that all users see the same product? How do you approach the team with the problem?

Response: Ask the participants to take a break at the least disruptive opportunity and go to speak with the developers in attendance while your co-moderator attends to the group. This will give you time to determine whether the previous version is still accessible. If it is, use it. If the previous version is not available, it is up to you whether you would like to get some feedback on the new version of the prototype or you might attempt to continue the focus group with activities that do not rely on the prototype. Be sure to document the change in the final report. Meet with the team as soon as possible to discuss the change in the prototype. Make sure the team understands that this may compromise the results of the activity. If they would like to do an iterative design approach, they should discuss this with you in advance so that you may design the activity appropriately.

Make sure that you inform product teams of “the rules” before any activity. In this case, before the activity, you would inform them that the prototype must stay the same for all focus group sessions. Be sure to inform them why, so that they will understand the importance of your request. Let them know that you want to make design changes based on what all groups have to say, not just one. Remember that this is the product team’s session, too. You can advise them and tell them the consequences, but be aware that they may want to change it anyway and it is your job to analyze and present the results appropriately (even if this means telling stakeholders that the data are limited because of a decision the team made).

In some cases, the team finds something that is obviously wrong in the prototype and changes it after the first session. Often this is OK, but they should discuss it with you prior to the session. If they do not discuss it with you and you find out during the session, it does not always invalidate the data if it is something that should be changed in any case. When working with a team, you must strike a balance between being firm but flexible.

Observers Make Themselves Known

Situation: You are interviewing a participant in the user room while the team is watching in the observation room. As time goes by, observers in the observation room begin talking louder and the team begins laughing. The participant appears to be ignoring it, but the noise is easily audible to you, so the participant must be able to hear it, too. All of a sudden, one of the team members decides to turn on a light because he is having trouble seeing. The observation room is now fully illuminated and the participant can see there are five people in the other room watching intently. Should you try to ignore it and hope it does not draw more attention or should you stop the interview and turn off the light?

Response: The participant should never be surprised to learn that people are in the observation room observing the activity. At the beginning of every activity, participants must be made aware that “members of our staff sometimes observe in the other room.” It is not necessary to state the specific number of people in the other room or their affiliation (e.g., research group, development team). Participants should also be warned that they may hear a few noises in the other room, such as coughing or a door closing but they should just ignore it. Their attention should be focused on the activity at hand. Some people like to show the participants the observation room and the observers prior to the session. We typically do not adopt this approach because participants can become intimidated if they know that a large group of people are observing.

In the situation above, if the participant is not facing the other room and has not noticed the observers, do not call attention to it (someone may turn the light off quickly). However, if the participant has seen the observers, simply ask the observers to turn off the light and apologize to the participant for the disruption. After the participant has left, remind the team how one-way mirrors work and explain that it may affect the results if the participants see a room full of people watching them. Participants may be more self-conscious about what they say and may not be honest in their responses. If you notice that the participant’s responses and behavior change dramatically after seeing the observers, you may have to consider throwing away the data.

To avoid this situation in the future, ask the observers to be quiet before you leave the observation room to conduct the interview and remind them how a one-way mirror works. It is also helpful to have another member of your team in the observation room (usually a notetaker) because that individual can prevent the situation from getting out of hand. If there are multiple sessions, observers may think that they have heard it all after the first participant. As a result, they start talking and ignoring the session. Explain to observers that every participant’s feedback is important and that they should be taking note of where things are consistent and where they differ. Be nice but firm. You are in charge. Observers are rarely uncooperative.

We had the unfortunate situation once when a participant actually said, “I can hear you laughing at me.” Despite assurances that this was not the case, the participant was devastated and barely spoke a word for the rest of the session. Amazingly, the observers in attendance were so caught up in their own conversation that they did not hear what the participant said!

Concluding Your Activity

At the conclusion of the study, you should thank participants for their time, give them a chance to ask any questions they may have, and remind them to keep the session confidential. If their participation was helpful and you think they might be qualified for future studies, ask them if they would be interested in participating in studies in the future. If so, add their name to your participant database (see Appendix A, Creating a Participant Recruitment Database). Escort participants out to the lobby or to the exit of the building and provide directions as needed or politely and quietly leave the field location.

Pulling It All Together

In this chapter, we have given you ingredients that will help you conduct any of your user research activities effectively. You should now be able to deal with participant arrivals, get your participants thinking creatively, moderate any individual or group activity, instruct your participants how to think aloud, and conclude a session successfully. In addition, we hope that you have learned from our experiences and that you are prepared to handle any awkward testing situation that may arise. In the following chapters, we delve into the methods of a variety of user research activities.