Chapter 6

Fostering Internal Markets

Internal markets bring external competition inside so as not be obsoleted by innovators outside.

IN THE LAST SEVERAL DECADES, Silicon Valley may have generated more innovations, start-ups, patents, initial public offerings, and wealth per capita than any other geographic region in the world. In particular, with 1% of the U.S. population, Silicon Valley generates 12% of its patents and 27% of its venture capital.1 A recent study finds Silicon Valley ranks first among all such ecosystems in the world and in terms of start-ups alone it is three times bigger than the second on the list, New York City.2 Moreover, many of these start-ups have grown to become highly successful, fast growing, and very profitable firms with huge market caps. One consultant in the Valley summarizes the success of the Valley thus: “Never has so much wealth been created in so little time by so few people.”3 The wealth they have created has been a boon not only to their founders but also to their employees, the state of California, and the whole U.S. economy. Silicon Valley has been so successful that cities, states, and countries all over the world have tried to emulate its success by initiating Silicon Valley–like clusters of their own: Silicon Alley, Allee, Beach, Bog, Fen, Forest, Glen, Gulf, Gorge, Hill, Plateau, Slopes, Wadi, are just a few of the many such imitations around the world.

What most characterizes Silicon Valley is probably a free market for ideas, funds, talent, and innovations.4 The entrepreneurial atmosphere is so intense that it attracts talent from other similar clusters around the world. Even Google, with the most generous working conditions of any corporation in the world, finds it difficult to prevent its talented employees from leaving to form start-ups of their own in the Valley.5 Would not corporations and even governments benefit from having within the organization a productive culture like that of Silicon Valley?6 How can one bring the outside market within the organization to ensure its survival, productivity, and growth? That is the subject of this chapter. That is the concept of fostering internal markets.

In reality, the situation within organizations is just the opposite of that in markets. Successful start-ups grow to become large organizations. Large organizations develop bureaucracies, which are characterized by a hierarchy of authority, numerous rules to guide employees' behavior, and numerous procedures to guide activities. Bureaucracies tend to be homogenous and monolithic. That is, various parts of the hierarchy all follow the same procedures and all ultimately report upwards to a single authority. Bureaucracies are not inherently bad. They develop with one predominant goal in mind—to keep the organization running smoothly and efficiently. A large, successful organization must ensure the satisfaction of its current customers and the future continuation of the past stream of profits. Thus, bureaucracies are designed to perpetuate the past that yielded success.

However, for these very reasons, bureaucracies inhibit radical innovations. Innovation is amorphous and risky. Bureaucracies are precise and predictable. Innovation requires embracing divergence. Bureaucracies ensure uniformity. Innovation thrives on quick decisions in response to a changing environment. Bureaucracies are slow moving, requiring numerous approvals for minor deviations. Innovation encapsulates the future. Bureaucracies institutionalize the past. Innovation is about capturing future markets and future profits. Bureaucracies are all about protecting past customers and past profits. Thus, bureaucracies tend to smother innovation. And the more monolithic and homogenous the bureaucracy, the less innovative it is. When a bureaucracy does produce innovations, it favors incremental or sustaining innovations that fit with its current skills, routines, and markets. Bureaucracies tend to overlook radical innovations that can transform markets or cannibalize current products. Chapter 2 underscores with examples how these issues led dominant incumbents to overlook the next big radical innovation that would have sustained and furthered its success.

For example, by 2005, Research in Motion (RIM) was the leading producer of smart phones with a dominant position. Its BlackBerry was a favorite of the corporate market because it offered two unique features, security and a miniature keyboard. A whole bureaucracy developed around phones that perfected these features. Cofounder Rick Lazaridis give this bureaucracy his stamp of approval, saying, “We will always work from the present status of the BlackBerry in terms of reliability and security, because that is what our users expect.”7 As a result, innovation around new evolving technologies and fast-changing consumer needs suffered. “Their overriding ambition was to protect the products instead of adapting to fast-changing customers tastes,” is how one reporter describes the culture within the firm.8 After Apple came out with touch-screen phones, the BlackBerrys with miniature keyboards seemed increasingly archaic and RIM's market cap declined sharply, from $78 billion in May 2008 to $7 billion in April 2012.

Is there an organizational structure that especially fosters radical innovation against the drag of bureaucracies? My research with Rajesh Chandy involving 24 face-to-face interviews and 194 completed surveys of executives responsible for new product development shows that internal markets can serve as an important antidote to bureaucratic structures.9 A few others have also urged the use of internal markets for this purpose.10 Internal markets bring into the organization the healthy aspects of the competition that exists outside the organization. Internal markets consist of teams of employees, business units, or divisions that at least partially compete with each other. The rivalry involves the freedom to compete to research, develop, or market alternate ideas, technologies, products, or business models for various consumers. Research teams could write proposals for funds, facilities, and talent to develop promising innovations. Other teams that have developed innovations could lobby business units to commercialize these innovations. Business units themselves would have some freedom to commercialize innovations even though these innovations may compete with existing products of other divisions.

Several caveats are in order at the outset. The selection of technologies or business models on which to compete must be restricted to those that build on the firm's current strengths or are likely to cannibalize the firm's current successful products. As such, the firm still maintains a strong interest and competence in such technologies or business models, so the internal competition does not degenerate into a mad rush into anything and everything. Even then, internal markets have many risks and costs, which this chapter addresses. Further, those employees, teams, or business units that lose out in this competition should not be punished. As Chapter 5 emphasizes, the rewards system in this competition must combine strong incentives for success with weak penalties for failure. Losing teams must be encouraged to “learn and move on.”

The structure of internal markets offers firms three important advantages.11 First, it helps the firm fight obsolescence. Every firm today lives with the prospect of dozens or hundreds of rivals, innovators, or entrepreneurs all over the globe planning on marketing products of the future that might cannibalize the firm's existing products. The essential logic of internal markets is to grow or bring within the firm such innovators that otherwise would flourish independently outside the firm. These innovators may then help the firm cannibalize itself before an outsider in the external market does so (see Chapter 2). Second, internal markets provide the firm with options. In most markets, rival technological platforms coexist. A firm may not be sure which technology will be the most successful in the future. With internal markets, a firm may support two or more technological platforms at the same time so that it has multiple options depending on which takes off in the future. Later this chapter addresses the potential duplication or lack of focus that having these options entails. Third, internal markets motivate employees to give their best. Competition resulting from internal markets spurs individuals or teams to do better than their rivals. Lack of competition leads individuals or teams to coast or, worse still, leads motivated talent to exit the firm. Thus, well-managed competition can lead to an increase in creativity and productivity.

Characteristics of Markets

What are the essential elements of markets? We can think of four primary characteristics of markets.12 These are:

These characteristics of markets lead to three important outcomes that are highly beneficial to the community at large.

Markets as Idea Generators

Well-functioning markets abound with fresh ideas. Entrepreneurs are constantly thinking up new and better ways to produce goods and services. They then build prototypes and seek out financing to commercialize these new goods and services. In particular, they tap angel investors and venture capitalists for funding for these ideas. For example, an average venture capitalist in Silicon Valley could get as many as five thousand unsolicited business plans a year.13 Large corporations that have not internalized the market for ideas may get just a handful. Although markets are rich in diverse ideas, corporations struggle with few homogenous ideas as employees labor under the burden of routines.

Having many diverse ideas is vital for innovation. For any problem, all that's needed is one good solution. The probability of hitting that solution increases with the number and diversity of ideas.14 The larger the pool, the more likely it will encompass a good idea. The greater the variance in ideas, the more likely it will encompass top ideas, besides the bad ones. Thus, in contrast to quality control, where manufacturers strive to raise the mean and reduce the variance, in idea generating, firms need to raise the number and variance of ideas. The market is rich in precisely what the corporation is poor—diversity and number of ideas. Internalizing the market will ensure that corporations have a rich set of ideas to begin the innovation process.

The firm can reach out to three groups to maximize the diversity and number of ideas: employees, consumers, and suppliers. The larger the corporation, the greater its tendency toward bureaucracy and lethargy; however, if all those employees were incentivized to generate ideas through fairs, contests, and prizes, the firm could harvest a wealth of ideas. With the growth of consumer online activity, consumers can also be tapped for ideas through properly constructed websites. These websites can also be structured to allow voting by consumers of the best ideas, similar to rating reviews in Amazon.com. Consumers can be motivated with prizes for winning ideas or just the honor of being the top idea person. Such idea generation from consumers in online forums has been called “crowdsourcing.”15 A similar system can be set up for suppliers. Thus, by properly incentivizing and organizing idea generation, firms can tap their pool of employees, consumers, and suppliers for ideas.

Markets as Talent Pools

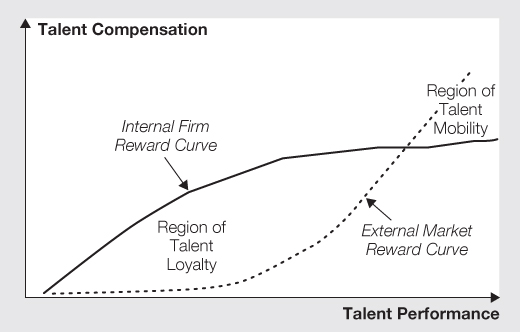

Employees love loyalty. Innovators love adventure. Our experience with corporations, especially large successful ones, is that they succeed in developing a large core of loyal employees. But they struggle with developing innovators. The reason for this situation is the failure to recognize and reward talent within. The reward for talent within organizations typically follows a declining response curve—superior talent earns higher reward but at a declining rate. In contrast, the reward for talent in the marketplace is exponential—superior talent is rewarded at an increasing rate (see Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 The Market for Talent

Beyond a point, these two curves intersect and then diverge further apart. Before that point, firms exist in the region of loyalty. Here, talent has no reason to leave the firm. Beyond that point, organizations fail to reward talent as much as the market does. That is the region of mobility. In this region, organizations that are not aggressively challenging their talent to innovate and not generously rewarding them will bleed talent to the market. Such talent will seek out organizations that are more innovation oriented or they will launch out on their own. Alternatively, such talent will leave to form start-ups that compete with their former employer. Scott Cook, the chairman of Intuit, had this to say about talent: “I wake up every morning knowing that if my people don't sense a compelling vision and a big upside, they'll simply leave.”16 Tony Fadell, sometimes referred to as the “Father of the iPod,” was employed by Philips before he tried to develop a music player on his own, failed, and was subsequently hired by Apple (see Chapter 7). The role of Philips in mobile music may well have been different if it had managed to retain and empower Fadell to develop a mobile music player for them.

To retain talent, some firms, such as Google, pamper their employees with extravagant amenities (see Chapter 5). These are small costs to bear for the highly profitable innovations that those employees could generate. But incentives and amenities are not enough. The most important motivation for attraction and retention of talent is the opportunity to shape the world of the future by working on the next big innovation. Internalizing the market for talent involves giving units adequate freedom within the corporation to attract talent and giving talent freedom to join projects and units that work on innovations that excite them.

Markets as Efficient Resource Allocators

Markets are great forums for the efficient allocation of resources. Essentially, sellers who produce better goods amass profits, which they can invest in even better products. Products that are duds do not sell, discouraging further investment in their production. In contrast, the resource allocation within an organization, especially a large one, is sticky. Resources normally flow from top to bottom. Top managers are prone to support their pet projects, the ones they developed, or on whose success they moved up the ladder. In such a process, old products suck resources way past their prime. Examples are GM's investment in SUVs, Kodak's investment in film photography, Microsoft's investment in MSN, Intel's investment in chips for PCs. However, markets outside are in a constant flux. Old products die out as innovations steal market share from them. Externally markets constantly and smoothly allocate resources to the most promising innovations. The challenge for large corporations is to internalize this efficiency in resource allocation in the market outside. They need to make sure that talented employees within the firm are not shortchanged for resources. Gary Hamel articulates this dilemma well: “It's ironic that companies pay CEOs millions upon millions to unlock shareholder wealth but seem incapable of funneling six- and seven-figure rewards to people who can actually create new wealth.”17

Large corporations have a thorough screening process to invest in projects. This screening tends to be highly risk averse and geared to avoid losses (see Chapter 3). Big innovations are risky and could easily be screened out in such a process. In contrast, the market outside involves small sums of money that are successively invested in a range of ideas. The market's concern is not loss avoidance but upside gain. Highly risky projects with a huge upside get funded in a portfolio of similar projects, even though many of them could well fail. All it takes is one big success amid many failures. Internalizing the market for resource allocation means replacing the top-down allocation with a bottom-up competition for funds. Innovators, individually or in teams, should be allowed to compete for a pool of funds. Senior managers should serve as referees rather than judges. To fully internalize the external market, at least some of the judges of these competitions should be future-oriented experts in the area, from the outside market—business and academia. Firms should slowly move their funds for research, development, and commercialization from a legacy model of supporting old favorites to a market model of supporting ideas, prototypes, and innovations generated by talent within or outside the organization.

Markets also have some negative outcomes that deserve to be discussed.

Cascades and Bubbles

The phenomenon of cascades and bubbles derives directly from the signaling present in markets. If many buyers are not well informed and make purchases based on the purchases of other buyers, markets can cascade onto some popular choices that are not necessarily good. Those choices become considerably overpriced yet hugely popular, resulting in bubbles. The Internet crash of 1999–2000 and housing crash of 2008–2009 are recent examples of an age-old problem. When the bubble bursts, a large number of buyers and sellers get hurt. Thus, markets are not always a panacea. Within a firm, cascades and bubbles may arise when decisions are based on votes, which themselves are influenced by comments of others rather than in-depth analysis of the options. Such signaling can occur if decision makers have access to others' evaluations or votes, such as occurs in some crowdsourcing setups. Cascades and bubbles can be minimized by encouraging decision makers to evaluate proposals on the merits of each proposal at hand and minimizing their access to signals from others.

Cutthroat Competition

Markets also lead to cutthroat competition. They wean out the inefficient and mediocre and reward the efficient and good. Although this is painful yet acceptable outside a firm, it can be traumatic within a firm and dysfunctional if not managed well. Indeed, the popular press is quite critical of internal markets for this one reason.18 Many employees join corporations because they do not want the risk, ruthless competition, and insecurity from being independent contractors or entrepreneurs in real markets. They love the paternal attitude and job security of large corporations. As Bob Gatto, vice president of business development at Nestle, says, “People come to a corporation for a [secure] corporate job.”19 Thus, many employees have a strong distaste for internal markets. However, such markets will be highly attractive to the most enterprising and talented employees. Indeed, carefully introducing internal markets into organizations could well stem the loss of talent to entrepreneurial ventures while motivating risk-averse employees to become entrepreneurial. The goal of the firm is to retain its brightest talent even if it means losing the security-minded employees for whom the office is too hot.

Lack of Cooperation

An essential element of the development of innovations within a firm is the sharing of ideas, cross-stimulation, and cooperation among various employees involved with development. Internal markets run the danger of destroying this healthy environment. To minimize this loss, firms can adopt a number of mechanisms to encourage cooperation. First, at quarterly or six-month intervals, various teams can present their research and progress at open seminars within the firm. All parties can then see the progress of the team, provide comments for improvement, as well as learn from advances and failure. Second, employees can be provided with monetary or other incentives for contributing ideas to teams other than their own. Third, all teams involved in serving a particular market, albeit with rival technologies or products, could be provided with some fraction of the reward of the team that does best and succeeds. This reward system would be similar to that within a conference in the NCAA20 competition. Teams within a conference compete aggressively to win the conference and go to a national bowl championship. But all teams share in the profits that accrue to the winning team. A relevant example is the sharing of a bonus by Andy Rubin, a vice president at Google in fall 2008. With the launching of the first Android phone, Rubin won a multibillion-dollar contractual bonus. He voluntarily shared this with his team of over a hundred employees, who each received between $10,000 and $50,000.21 In general, the firm needs to emphasize that the goal of internal competition is not for one team or individual to beat another but for the whole firm to explore and advance a variety of avenues due to the uncertainty of knowing which particular one will best succeed.

Failure

One of the results of competition in the market, especially in the development and commercialization of innovations, is that many such efforts fail. All these failure can be costly. However, in the external market, these costs are borne by entrepreneurs and those investors who decided to back the entrepreneurs at their own risk. However, in the case of internal markets, failure is borne by the firm that institutes and supports such internal markets. Because only a few innovations succeed, the cost of failure can be high. But as Chapter 3's discussion on embracing risk reiterated, this cost is one that the innovator must be willing to bear. Reluctance to accept failure and learn from it leads to risk aversion, inertia, and lack of innovativeness. Indeed, internal markets are means by which a firm can institutionalize the trait of embracing risk (see Chapter 3). The question then is not whether a firm should bear such costs, but to what extent it can bear such costs and how much it learns from failure to do better in the future.

Duplication

When internal markets are tolerated, encouraged, and established within a firm, it inevitably leads to higher costs from duplication when two or more groups, business units, or divisions try to serve the same market of consumers with rival products or technologies. To do so effectively, they need resources in the form of budgets, talent, and space. Thus, the firm may have to double the resources it devotes to serving one market. If the outcome is two competing but independently viable units, then this cost will be justified. If the outcome is the successful marketing of an innovation that otherwise would have been overlooked, then the cost is certainly justified. However, if one unit fails to produce a viable or successful product, then the investment in that unit seems wasted.

The firm has to evaluate all such waste against two pros. First, with internal competition comes the potential benefit of bringing within the firm innovations that would otherwise have emerged outside in the open market. One criterion that the firm could use is the danger of cannibalization from outside. How likely is it that a potential alternate technology would be developed and commercialized by a competitor and subsequently cannibalize the firm's successful products? If such a probability is very small to zero, then the firm need not focus on such a technology. The higher this probability, the greater the resources the firm needs to devote to that technology. Second, with internal competition comes the potential benefit that the firm does not focus all its resources on a single technology that subsequently does not bear fruit or becomes obsolete.

Consider, for example, GM. As discussed in Chapter 4, in the 1990s and 2000s the firm spent over a billion dollars on the hydrogen fuel cell as an alternative to the gasoline engine. However, a variety of alternatives to the internal combustion engine were on the horizon, including the hybrid engine, lithium-ion battery, methanol cell, liquid natural gas–based engine, and alcohol-based engine. GM spent most of its resources on the hydrogen cell at the cost of developing or at least exploring alternate technologies. The root problem may have been lack of internal competition. Without such competition, research resources were devoted on the one technology picked by managers at the top. Initial investment in talent and resources would have led to further investments, as talent drawn for one technology would tend to see it as the best. As it turned out, the hybrid technology (pioneered by the Toyota Prius) and then the lithium-ion battery (pioneered by Tesla) made more rapid inroads into the market than the hydrogen cell. In particular, the lithium-ion battery was pioneered by Tesla for less than $100 million. A portfolio strategy, with rival teams focusing on rival technologies, may have initially appeared redundant. However, such a strategy may have led to a more efficient and productive use of the over $1 billion that GM spent on the hydrogen cell with little to show for it.

Lack of Focus

Competition in the external markets means dozens to hundreds of individuals, entrepreneurs, and firms competing to serve a single market with some innovation. Lack of focus in not an issue when the innovation is the primary focus of these entities. However, fostering internal markets within a firm can create dozens of entities competing against each other. Such competition runs the risk of diluting the firm's focus on its primary task. After all, a generation of experts have emphasized that firms are better off focusing on their core competence than on diversifying into unrelated businesses.22 Thus, the firm that embarks on internal markets must ensure that the competition is about alternate technologies that are central to the firm's mission and do not take the firm into completely unrelated fields.

For example, it makes eminent sense for Philips, a lighting company, to encourage competition among its employees for the next platform technology that will empower its lighting products, be it incandescence, fluorescence, light-emitting diodes (LED), or microwave electrodeless discharge (MED). These are all technologies with plausible futures in lighting. It does not make sense for Philips to initiate competition for engine technologies, which are at best peripheral to its mission. Similarly, the race for the next technology that will power the automobile engine of tomorrow is not yet decided. It makes sense for GM, an automobile company, to have measured investments and some degree of competition among teams for all of the rival technologies listed above. It does not make sense for GM to initiate internal competition for lighting technologies, which is peripheral to its mission.

Implementing Internal Markets

We can classify organizations by the extent to which they generate and select ideas or innovations. Using two levels, internal or external to the firm, on each of these two dimensions gives us four cells (see Table 6.1). The classic firm (for example, Apple) is one in which innovations are generated primarily by internal employees and then selected by internal managers.

Table 6.1 Classification of Organizations by Degree of Internal Markets

| Selection of Innovations | Generation of Innovations | |

| Internal | External | |

| Internal | Classic Firms e.g., Apple | Classic Publishers e.g., HarperCollins |

| External | Classic Universities e.g., Stanford | Innovation Hosts e.g., YouTube |

Source: Adapted from Terwiesch and Ulrich, Innovation Tournaments.

Classic universities are those where ideas in the form of papers are generated internally but selected for publication by external journals. Publishers may be considered a form where innovations are generated externally by various authors but selected internally by a small group of acquisition editors. Finally, we come to innovation hosts, which serve merely as a platform where outsiders can generate innovations and other outsiders vote for their favorites. These platforms are highly dynamic, highly efficient, and very contemporary. Ideally, fostering internal markets means moving the organization from the top left cell to the bottom right cell. However, such a dramatic shift remains an aspiration that will be very difficult to implement in the short term, if at all. In most cases, firms can steadily increase internal markets by adopting one of several organizational forms as explained next.

A question the reader might ask is why should firms not emulate Apple, which used an internal-internal mode? Apple did so under the direction of Steve Jobs. His deep, intuitive understanding of consumers' future needs is highly unusual. If a firm does indeed have a Steve Jobs, then it could successfully employ the internal-internal mode. But for most firms with limited talent, moving to external-external mode ensures bringing the market within for productive generation and selection of ideas.

An important principle to consider is having separate processes for evaluating radical and incremental innovations. Incremental innovations are improvements in design or components within existing platform innovations. Radical innovations are the start of new platform technologies based on entirely new scientific principles (see Chapter 2). 3M makes it a point to keep the process for evaluating radical innovations separate from that for evaluating incremental innovations.23 An entirely new team, not one wedded to and invested in the old technology, evaluates the radical or platform innovation. This way, the radical innovation is not viewed through the lens of the old technology. Doing otherwise will lead to watering down the radical innovation or entirely rejecting it (see Chapter 3).

Several organization forms can slowly introduce internal markets to an organization. These forms embody some aspect of an internal market, but they are sufficiently local that they do not require a radical change in organization structure. They are listed in the order of increasing commitment of resources, space, funds, and internal markets. As a result, they are increasingly costly in terms of employee tension, resource commitment, and management time. But at the same time, they are also increasingly productive in terms of stimulating, generating, or commercializing innovations.

Idea Fairs

Subu Goparaju, senior vice president at Infosys, said that the company receives a great number of ideas from employees. However, 90% of the ideas are not valuable, 9% of the ideas are okay, and less than 1% are great. The problem is identifying the 1% while, as he says, “The 99% need to be engaged.”24 As emphasized earlier in this chapter, generating a large number of ideas is a strength, not a weakness, as it increases the chance of finding one great idea. However, screening ideas is a challenge. The idea fair is one solution. The fair provides a mechanism to screen the 1%, while the chance to win the reward(s) for the winner(s) can motivate the 99%.

An idea fair is a periodic event where individuals or teams propose ideas to judges for seed funding. The fairs could take the form of research seminars, a day or week where all participants can display their ideas, or a website that has descriptions of each idea. A team of judges then selects ideas. The judges may be drawn from peers, senior managers in the organization, or experts from outside. Participants may be encouraged to vote on other ideas excluding their own. The judges may use such votes in arriving at their judgment. After a review process, managers may decide to support the best ideas with funds or release time for employees. The output would be a formal proposal for substantial funding.

For example, each year Google sets aside one week called Innovation Week. During that week, employees can pitch their ideas to win greater support and resources. As another example, in 2010, PwC initiated a competition where teams of employees all over the United States could compete with proposals for helping the firm grow by 25% in the next planning cycle. Judges for the competition were drawn primarily from within the organization. These are forms of internal markets for ideas that are relatively easy to initiate and pay off right from the start, although they provide only a starting point and not a finished innovation.

Research Contests

In this case, resources are made available for competing proposals by individuals or teams of employees. The proposals would have to show a body of completed work and an adequate market for the potential innovation. The reward would be funds, facilities, or talent to develop the innovation in a one- to three-year time frame. This form of internal competition requires more investment from the firm but also delivers more output than the idea fair.

For example, 3M runs a competition for seed funding for teams that often form between divisions and groups to work on new technologies and products. Both 3M and Google have a feature where an employee who uses his or her (15% or 20%) time for an innovation project can solicit coworkers to contribute their (15% or 20%) time to the his or her project. This is an excellent system for three reasons. First, it relies on the wisdom of the crowds. Employees are likely to donate their own time to someone else's project. Thus, employees vote with their feet for the project they think is most deserving. Second, it reduces the onus on management to evaluate hundreds of ideas and projects. Third, it puts the burden of proof on the employee to establish the credit worthiness of his or her own project by winning support from coworkers. Such support in the form of other employee's time increases the progress on the project.

Commercialization Contests

Commercialization contests would be for completed research projects that have produced a prototype that is almost ready for commercialization. The team that has developed the innovation would then have the option to present the proposal for commercialization to various business units within the corporation. It's best to have a two-way competition among the prototypes for acceptance by a business unit and among business units for adoption of a prototype. The final decision could rest with experts within and outside the firms, based on past record and fit with the current business's portfolio. This is a serious form of internal market that requires considerable involvement and support from top management and business units. However, it provides an outlet for commercializing innovations that might otherwise stay on the shelves of the firm's laboratories. It addresses a persistent problem facing some firms with large R&D labs (such as Yahoo!, 3M, Microsoft). In the words of a former VP of Labs at HP, “Our problem is not generating innovations. Our problem is getting them out of the door.”

Contest for Internal Start-Ups

Groups that have already developed and tested an innovation compete for a mandate from senior managers to commercialize the innovation by starting up a new business unit for this purpose. This form of internal market requires a huge commitment of talent, resources, and time from management. But it has the potential for substantial payoff if the commercialization is successful.

Competing Divisions or Business Units

Two or more divisions or business units may compete with each other for the same market with alternative technologies. We may think of the two divisions as two rival small firms within the organization. Each is attuned to the latest technologies in order to best serve consumers' emerging needs. For example, in the early decade of the home printer market, HP housed the inkjet technology and the laser technology, each in a rival division. Each division could promote the technology in competition with the other division. As it turned out, neither technology was universally superior to the other. This healthy competition ensured that both technologies got adequate support. They ended up serving different consumer segments while HP dominated the home printer market.

Autonomous Units

A firm can entrust autonomous groups within a corporation with a secret or semisecret mission to develop an innovation without interference from the parent corporation or division. A term sometimes used for such a unit is skunk works. The term probably originated with Lockheed Martin's Advanced Development Programs (ADP), which is responsible for some well-known aircraft design, including the U-2, SR-71 Blackbird, the F-117 Nighthawk, and the F-22 Raptor. Another good example is IBM's Boca Raton division in the early 1980s, which was entrusted with developing the PC. The parent corporation, heavily focused on the mainframe, was skeptical or opposed to any involvement with microcomputers. On the one hand, the Boca Raton division, on the other hand, given the resources, autonomy, and talent, developed and successfully marketed the IBM PC in one year. Of all forms of internal markets, autonomous units and competing divisions involve the greatest commitment of resources, talent, and management time. However, if they are skillfully managed, they can ensure the commercialization of potentially profitable innovations.

Divestiture

A divestiture is a group or division that is separated from the parent and given full autonomy to pursue a special product market. There are two major forms: spin-off and management buyout. The spin-off is publicly traded on the stock market and thus has public ownership. A management buyout is the purchase of a unit responsible for an innovation by current managers of the unit. In either case, the parent can retain an interest in the divestiture and an option to buy it back if it turns out to be highly successful. My coauthored research on the topic indicates that although spin-offs may lead to higher initial sales and profits, buyouts lead to higher sales and profits in the long term.25 The probable reason is that the owner managers (of buyouts) are more interested in long-term payoffs than the agent managers (of spin-offs).

In the last three forms of these organizational structures, perhaps the hardest factor to deal with is the assignment of talent to the new venture. This talent is no longer available to the parent organization. Senior managers may be loath to part with talent, but the organization must keep in mind the greater good. Keeping talent involved in a divestiture in which the parent has a stake has a greater potential payoff, compared to the loss of talent departing in frustration over noncommercialization of their innovation. Moreover, highly entrepreneurial individuals are more likely to stay with a corporation when given the task of commercializing a challenging innovation than managing an existing product or service. For example, in the 1970s Xerox developed most of the innovations of the computer age in its famed labs, PARC, but commercialized only a couple. Due to this failure to commercialize, much of the talent in Xerox's labs left to start up their own ventures or to join firms that commercialized their innovations.

In the first four of these forms, the decision maker who decides who wins and who loses is typically within the organization. That is, a senior management team will decide who wins and proceeds to the next round or stage of development, and who loses and will have to terminate their effort. To better internalize markets, it's best to have external experts included in the decision team or at least make available to the decision team the opinion of experts. In the last of these forms, the decision maker is the market of consumers outside the firm. The market decides which product or technology is better and thus who wins. Letting external consumers decide is the most efficient form of internal markets but also the most costly in terms of investing funds, duplicating resources, and the emotional cost to employees. Thus, managing internal markets is critical for best results.

Managing Internal Markets

The success of internal markets depends primarily on managing this force for innovation. The success depends on determining how to incentivize internal markets, when to set up internal markets, and when to terminate them. Table 6.2 lists a large number of factors that dictate when to set up and when to terminate. The decision to terminate internal markets is relatively straightforward. When the group, division, or team has failed to develop a viable, commercializable, or successful new product, then it needs to be terminated. However, certain internal and market conditions provide strong reasons to set up internal markets.

Table 6.2 Criteria for Setting Up Internal Markets

| Criterion | Favoring Internal Markets | Disfavoring Internal Markets |

| Business model uncertainty | Two or more business models are possible with uncertainty as to success | Industry has coalesced on one business model |

| Technological uncertainty | Two or more rival technological platforms with uncertainty as to success | Industry has coalesced on one technology |

| Emerging niche | Emerging niche threatens firm | No new products or market niches on horizon |

| New product threshold | Firm has a high profit threshold for new products | Firm has low profit threshold for new products |

| Organizational inertia | Firm is slow to accept new ideas and innovations | Firm is quick to embrace new ideas and innovations |

| Organizational focus | Firm is focused on protecting its current technology or business model | Firm can focus on multiple rival technologies |

| Market potential | Huge market potential for rival products or technologies | Market is mature or declining |

| Talent availability | Firm has adequate talent to support competing teams or divisions | Firm faces a talent crunch |

| Resources for duplication | Firm has adequate resources to support internal markets | Firm faces a financial crunch |

Incentivizing Internal Markets

Internal markets could easily degenerate into destructive internal competition, in which competing groups withhold information from each other, undercut each other for resources, and work explicitly for the downfall of the competing group or division. Such internal competition was responsible for the downfall of Sony's MP3 player even though it was introduced before the iPod (see Chapter 2). In this case, the self-destruction was motivated by requiring all business units to reach a consensus. This policy meant that the business unit responsible for the MP3 player was held captive to the goals of the movie and music businesses. The latter were afraid that success from an MP3 player would undercut royalties from sales of movies and music. Incentivizing internal markets is finding the sweet spot between the lack of productivity from no competition to self-destruction from hypercompetition.

The sweet spot results from properly distributing incentives among individuals, members, and teams. For example, the founder and CEO of Resources Global Professional, a consulting firm, set up a system where one-third of incentives are based on each of individual performance, team performance, and company performance. Another scheme would be to encourage competition between groups with the winner's innovation project selected for further development, but the monetary reward shared equally with all teams that participated. Still another scheme is to reserve a portion of the incentive to individuals or teams who contribute to other teams. Whatever the form of incentives, requiring consensus among competing teams generally works to undermine healthy competition, as happened at Sony.

As Chapter 5 argues, incentives are powerful means to motivate innovation. Properly designed, they can encourage productive competition and discourage self-destructive competition.

Setting Up Internal Markets

Here are some important conditions when a firm should seriously consider setting up internal markets.

First, internal markets are called for when multiple business models seem viable with uncertainty as to which one will prevail. For example, around the year 2000, Internet firms were unsure about what would be the best means of profiting from the internet. Possible business models would be subscription-based portals (AOL), advertising-based portals (Yahoo!), search (Google) or network communities (Facebook). Microsoft itself launched MSN, which obtained revenues from banner ads. However, it squelched a search-based model that grew spontaneously within the firm for fear that it would cannibalize its banner ad business (see Chapter 2). This would have been a good situation for internal markets. Microsoft could have enabled search-based advertising as a separate business unit within the corporation.

Second, internal markets are called for when two or more rival technological platforms coexist with uncertainty as to which will prevail. For example, in the automobile business, several auto engine technologies vie to be the auto engine of the future: internal combustion engine, hybrid ICE and electric, hydrogen cell, methanol cell, liquid natural gas fuel engine, ethanol fuel engine, or lithium-ion battery. In the 1990s and early 2000s, GM made a bet on hydrogen and invested over a billion dollars on the hydrogen cell. A better strategy would have been to float two to four divisions, each supporting a different technology. Competition would have determined which one would succeed.

A third condition favoring internal markets is an emerging product or market that threatens a firm's existing product or market. The natural reaction of the firm is to buckle up and work harder on its existing product to make sure it does not lose its existing market. Such a strategy is rational. However, this is also a great condition to set up another division or business unit that explicitly caters to the new market without being encumbered with responsibilities for the current market. For example, when the digital camera market started to emerge, Kodak had a strong position. Yet its preoccupation and focus on the film market hindered its full involvement and development of the digital photography market. It lost leadership in the latter market to Japanese firms. This would have been a good situation to set up an entirely new division that focused entirely on the digital market without any responsibilities or ties to the film market.

A fourth factor favoring internal markets is the presence of a high threshold for introducing innovations. Some firms are so large that they set up a high threshold for introducing new products. For example, one firm, with over $100 billion in sales, has a threshold for radically new products that requires a new product to generate $1 billion in sales in three years. For most such new products, this is close to an impossible goal to meet, especially if takeoff of new products averages six years. Yet for such a large firm, going after a large number of niche markets can become a distraction for management, which needs to focus on its primary business. In such a situation, the use of spin-offs or buyouts to commercialize new products should be seriously considered. The firm can take a stake or option in the spin-off or buyout to ensure it regains its initial investment. Moreover, should the innovation take off, the firm is in a preferential position to buy and integrate the divested unit.

Conclusion

This chapter describes why firms should set up internal markets to preempt competition from innovative start-ups and discusses different forms to achieve this.

- A firm exists because it has fine-tuned a means of producing and delivering a product or service to a segment of consumers far more effectively and efficiently than any other firm. That fine tuning ensures a stream of profits. Firms develop bureaucracies to protect this stream of profits. Bureaucracies are efficient at managing current resources. They are weak at developing innovations and may even kill off innovations.

- All over the world, millions of entrepreneurs are hungry for the profits from current incumbents. They are designing the next big innovation with the firm's customers in mind. Markets are strong where firms are weak. They channel resources to those entities that are most innovative. Markets weed out lumbering giants and foster innovative start-ups.

- Incumbents need to develop internal markets to keep innovation thriving within. Bringing the market inside the firm can help a firm stay ahead of this diverse, unseen, and worldwide competition. Such markets provide a forum for innovators to offer alternatives and share information, allowing managers to choose among alternatives and provide support for those selected.

- In general, letting more employees and outsiders participate in the generation and selection of innovations ensures a bottom-up rather than top-down approach. In so doing, the firm can benefit from the wisdom of the crowds.

- To ensure success, firms also need to watch out for and control negative effects of markets: cascades and bubbles, cutthroat competition, lack of cooperation, duplication, and outright failures.

- Particular forms of internal markets include idea fairs, research contests, commercialization contests, competing business units, autonomous units, and divestitures.

- The most important rule in implementing markets is to incentivize employees and teams to ensure the productive development and commercialization of innovations and the avoidance of negative consequences of markets.

The history of business shows that markets have frequently generated new entrants that have displaced mighty incumbents. Internalizing markets is a means of preempting the market in this game.

1 Index of Silicon Valley, Silicon Valley Community Foundation (2012). http://www.jointventure.org/images/stories/pdf/2012index.pdf

2 “Silicon Valley, London, NYC,” TechCrunch (2012). Retrieved April 11, 2012, from http://techcrunch.com/2012/04/10/startup-genome-compares-top-startup-hubs/

3 Hamel, Gary, “Bringing Silicon Valley Inside,” Harvard Business Review (September-October, 1997): 71–84.

4 Valikangas, Liisa and Gary Hamel (2001), “Internal Markets: Emerging Governance Structures for Innovation,” paper presented at the Strategic Management Society, 21st Annual International Conference, San Francisco, 2001.

5 Vascellaro, Jessica E., “Google Searches for Ways to Keep Big Ideas at Home,” Wall Street Journal, Technology, 253, no. 141 (June 18, 2009): B1–B5.

6 Hamel, “Bringing Silicon Valley Inside.”

7 Libbenga, Jan, “BlackBerry Boss Blows Raspberries at iPhone,” The Register (November, 8, 2007).

8 Reguly, Eric, “Failing in Face of Apple's Next Big Thing,” The Globe and Mail (January 28, 2012).

9 Chandy, Rajesh and Gerard J. Tellis, “Organizing For Radical Product Innovation,” Journal of Marketing Research, 35 (November 1998): 474–487.

10 Halal, William E., Ali Geranmayeh, and John Pourdehnad, Internal Markets: Bringing the Power of Free Enterprise Inside Your Organization (New York: Wiley, 1993); Valikangas and Hamel, “Internal Markets.”

11 Birkinshaw, Julian, “Strategies for Managing Internal Competition,” California Management Review, 44 (Fall 2001): 21–38.

12 Valikangas and Hamel, “Internal Markets.”

13 Hamel, “Bringing Silicon Valley Inside.”

14 Terwiesch, Christian, and Karl T. Ulrich, Innovation Tournaments (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2010). http://www.InnovationTournaments.com

15 Howe, Jeff, “The Rise of Crowdsourcing,” Wired (2006). http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/14.06/crowds.html

16 Hamel, “Bringing Silicon Valley Inside,” 9.

17 Ibid.

18 Rosen, Evan, “The Hidden Cost of Internal Competition,” Bloomberg BusinessWeek (November 10, 2009). http://www.businessweek.com/managing/content/nov2009/ca2009113_427287.htm; Heffernan, Margaret, “Dog Eat Dog,” FastCompany.com (July 8, 2008). http://www.fastcompany.com/resources/talent/heffernan/072804.html

19 Gatto, Bob, “Culture of Innovation at Nestle,” Advisory Board Meeting, USC Marshall School of Business, May 15, 2012.

20 National Collegiate Athletic Association.

21 Wingfield, Nick, “The Man Behind Android's Rise,” Wall Street Journal (August 17, 2011): B1–B2.

22 Prahalad, C. K. and Gary Hamel, “The Core Competence of the Corporation,” Harvard Business Review (May-June, 1990): 79–91.

23 Ouderkirk, Andrew J., “Culture of Innovation at 3M,” Advisory Board Meeting, USC Marshall Center for Global Innovation, May, 2011.

24 Goparaju, Subu, “Culture of Innovation at Infosys,” Advisory Board Meeting, USC Marshall Center for Global Innovation, May, 2012.

25 Rubera, Gaia and Gerard J. Tellis, “Spinoffs Versus Buyouts,” working paper, USC Marshall School of Business, 2012.