Chapter 3

Embracing Risk

For us innovation means being willing to bet hundreds of millions of dollars on a new drug, labor to bring it out over a decade, fail, and then be willing to try all over again.

—Kevin Sharer1

THIS QUOTATION FROM FORMER Amgen CEO Kevin Sharer, who grew the company's revenues from $3.6 billion to $16 billion in about ten years,2 reveals a deep understanding of an essential feature of innovation and risk taking: that failure is intrinsic to the process and the innovator's best attitude is to embrace it! Taking risks really means embracing failure, in order to learn from it and do better in the future.

Innovations may fail at any of the stages of idea screening, development, prototype testing, market testing, commercialization, and post commercialization. Risk is due to the uncertainty of success during the stages of developing and commercializing an innovation. That is, risk is proportional to the degree of uncertainty about the outcome of the innovation and the costs involved in the innovation.

Sources of Risk: Innovation's High Failure Rate

The riskiness of innovations arises from at least five sources.

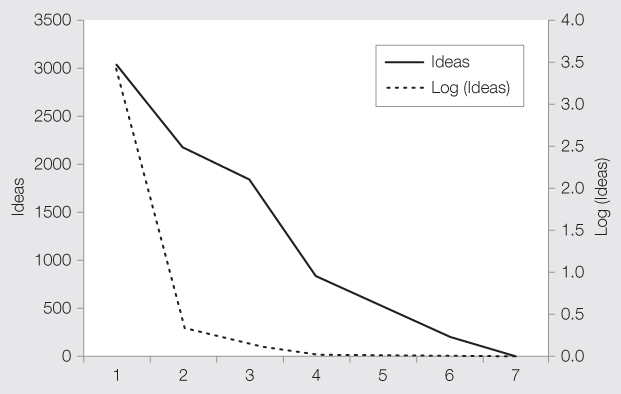

First, the loss or failure of projects increases as they move from the stage of ideation to that of ultimate commercialization. A new product normally goes several stages of development. Managers start off with a large numbers of ideas, screen these to a smaller set, research the promising ones, develop a still smaller set, realize prototypes of some of these, test market a few, and launch one or two new products. There is a tremendous loss as the firm goes from ideas to successful launches. One study across a large number of industries found that it took over three thousand ideas to arrive at a few successful products; thus, the loss function for innovations is very steep (see Figure 3.1). This loss is extremely high in the pharmaceutical industry. For example, in order to produce the one highly successful cholesterol drug, Zocor, Merck screened about ten thousand chemical compounds, ran clinical trials for more than a dozen, and tried out a handful in human subjects.3 When bringing new ideas to fruition as new products, managers incur increasing costs without being certain which idea will be the best. This is the first source of risk.

Figure 3.1 Innovation's Loss Function

Source: Adapted from Stevens, Greg A., and James Burley (1997), “3,000 Raw Ideas = 1 Commercialized Success!” Research Technology Management, 40, 3.

Second, numerous studies suggest that the failure rate for even commercialized new products is very high. Here failure would mean that the new product is not ultimately profitable and has to be withdrawn or discontinued in the market. Estimates of the rate of failure range from as low as 20% to a high of 90%.4 A recent survey of 416 respondents across industries finds that firms on average commercialized only one successful product out of every eleven projects started.5 Thus, even after all the screening, research, testing, and marketing, a new product may not become an ultimate success in terms of profit. This is another source of risk.

Third, innovations vary greatly in their commercialization profile. Some innovations can be slowly launched in the market over time from segment to segment (waterfall strategy). Others need to be launched on a large scale to whole market in one go from day one (sprinkler strategy). For example, Fred Smith, who launched Federal Express needed to start with a large countrywide network of costly planes, trucks, and employees (see case history later in this chapter) so that mail could be picked up and delivered as required by the sender. A waterfall strategy reduces risk as it allows for a slow build-up in expenses, which can be covered with growing revenues. A sprinkler strategy requires an enormous investment up front. This need for massive investment with no guarantee of revenue is a third source of risk.

Fourth, the takeoff in sales of a new product is an early sign of ultimate success. However, sales of a new product may take several years to take off. Estimates of the time from introduction to takeoff vary from a few years for digital products to several years for household durables.6 However, these estimates are for successful new products. In the case of any radically new product that is now being launched, the manager does not know whether it will fail or succeed. In my discussions with managers, I have found that junior managers who are immersed in the new product are willing to wait. But senior managers may be impatient with a long time to takeoff because expenses keep mounting during the wait. This wait for takeoff is the fourth source of risk.

Fifth, some innovations need to grow very rapidly to be viable in a fast-changing environment. For example, Jeff Bezos, who launched Amazon, figured that his start-up needed to grow very rapidly in order to be viable in the rapidly growing Internet world (see case history later in this chapter). Rapid growth requires huge investments that exceed the revenues generated initially. Increasing growth during the first few years after commercializing may be euphoric but involves increasing losses with no guarantee of ultimate success. This is the fifth source of risk.

This discussion shows that risk arises from a variety of sources. Most important, an innovation has a high probability of failure at one of several stages of development; that is, innovation is inherently risky. Innovation tends to lose its glamour when people realize its high failure rate and inherent risk. As one scholar commented, “The popular (and sometimes the scholarly) enthusiasm for risk taking in the entrepreneurial process wanes considerably at the prospect of failure.”7 Moreover, society looks unfavorably at risk, considering failure to be shameful, more so in some cultures than others.8 Two scholars on the issue put it this way, “Society values risk taking but not gambling. And what is meant by gambling is risk taking that turns out badly.”9

Thus, embracing risk really means embracing failure. Amgen CEO Kevin Sharer says of failure, “We fail most of the time even when we get the science right.”10 Thomas J. Watson Sr., the former CEO who grew the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company into a worldwide industry we know as International Business Machines (IBM), once said, “The fastest way to succeed is to double your failure rate.”11

Specifically, how do most people handle risk? Research indicates that response is not quite rational but still predictable, as seen in three phenomena called the reflection effect, the hot-stove effect, and the expectations effect.

The Reflection Effect: Asymmetry in Perceived Risk

Consider a choice from the following two alternatives:

Two psychologists, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky,12 found that when faced with this choice, 80% of subjects in experiments preferred alternative B even though alternative A had a higher expected value of $3,200. The latter payoff comes from multiplying .8 into $4,000. The authors explained that people prefer a sure gain over a gamble in which they could win even more but also lose everything.

Now consider a choice of the following two alternatives:

When given this choice, 92% of subjects chose C over D even though C has a greater expected loss ($3,200) than the loss of $3,000 in D. The reason is that people prefer to gamble on a big loss if there is even a small chance that they may lose nothing. Interestingly, the preference for sure versus uncertain payoff reverses when the payoff is stated in losses (C, D) rather than gains (A, B). The psychologists called this reversal the reflection effect. This effect is part of a theory of risk that they called prospect theory, for which Kahneman later received the Nobel Prize.

On the one hand, successful incumbent firms with a reasonably secure profit stream can be said to be operating in the domain of gains, as in alternatives A and B.13 They prefer the surety of a small steady stream of profits to the gamble of innovations, in which they might win big but also win nothing. On the other hand, start-ups or new entrants (or failing incumbents) can be thought of as operating in the realm of losses, as in alternatives C and D. They are willing to gamble on innovations with the potential of a big win, rather than do nothing and face no gains at all or continued losses. Thus, successful incumbents and start-ups may have opposite propensities to risk. Incumbents, who typically have a steady cash stream, look skeptically at potential innovations and ask, “Why? What do I have to gain?” They are risk averse. Entrepreneurs and new entrants look hopefully at the same innovations and ask, “Why not? What do I have to lose?” They are risk seeking. The two parties are at either end of the reflection effect.

The high failure rate of innovations suggest that developing innovations requires committing resources without certainty of outcomes, patience in the face of mounting losses, and willingness to accept failure. The reflection effect suggests that these traits may not come naturally to incumbents. In particular, incumbents may tend to have the opposite traits: low tolerance for uncertainty, impatience with losses, and low tolerance for failure. The latter traits result from incumbents' satisfaction with the current stream of profits from their products and their belief that carefully nurturing current products will ensure continued profits in the future. Subu Goparaju, senior vice president at Infosys, encapsulates the problem this way, “The tendency is to defend what you have already achieved. … Everyone is empowered to say no and no one is empowered to say yes.”14 Start-ups, which have no such stream of profits, may be more likely than profitable incumbents to commit funds to innovations, tolerate uncertainty, and be patient with losses.

For example, during the 1970s, prior to the onset of digital cameras, Kodak had a continuous stream of profits. That success brought risk aversion and lack of innovation. Kodak's “executives abhorred anything that looked risky or too innovative because a mistake in such a massive manufacturing process would cost thousands of dollars. So the company built itself up around procedures and policies intended to maintain the status quo.”15

Apple became one of the most valuable companies in the world due to a string of highly innovative products under the leadership of Steve Jobs. Jobs explains how he overcame the reflection effect at Apple, “Almost everything—all external expectations, all pride, all fear of embarrassment or failure—these things just fall away in the face of death, leaving only what is truly important. Remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose.”16

The Hot-Stove Effect: Learning from Failure

The term hot-stove effect was coined by two professors, Jerker Denrell and James G. March, to explain incumbents' risk-aversion.17 It is a complementary explanation to the reflection effect. They justify the term from the following quotation by Mark Twain:

We should be careful to get out of an experience only the wisdom that is in it—and stop there: lest we be like the cat that sits down on a hot stove lid. She will never sit down on a hot stove lid again—and that is well; but also she will never sit down on a cold one.18

Innovations represent novel but risky options. Succeeding with innovations involve errors. In the course of exploring alternatives, firms may make mistakes, encounter setbacks, or fail. Moreover, if the firm is testing a new and unfamiliar technology, such mistakes and failure may be more common, especially if performance improves with experience. In such situations, early experiences with a new technology may be less favorable than its long-term average or the average that comes with experience. Similarly, in the face of very risky innovations, with a large variation in results, a small sample of initial tests may well come up with greater failures than that from the long-term average of tests. It is imperative that the innovator learn the right lessons from the failures. Proper and deep reflection on the failure may be necessary to uncover the true lessons. However, the hot-stove effect leads to a bias against alternatives and innovations that are very risky (variable returns) or that require experience for success.

For example, in the last few minutes of a close basketball game, players on a team normally try to give the ball to their clutch players, the players who shoot baskets with a supposedly high success rate during the intense pressure of the last few minutes of a close game. Such players are also much higher paid than regular players. However, research shows that clutch players are not better in shooting performance in the last few minutes of a close game than at other times of the game.19 Why then does the myth of clutch players persist? It does so because clutch players want the ball and are unafraid to take risky shots under pressure. They do fail in those moments and they probably know they failed in those moments in the past. However, they learn from the failure—not that taking a shot could result in a loss as in the past but that taking a shot with cool focus and proper position could result in success. Michael Jordan says in a Nike ad, “I've missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I've lost almost 300 games. 26 times I've been trusted to take the game winning shot and missed. I've failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.”20 From his failures, Jordan learned what to avoid and what to strive for to achieve success.

In his book To Engineer Is Human, Henry Petroski details the failures and disasters that occurred with numerous designs, mostly of bridges but also of buildings, ships, and planes.21 The learning from the ensuing disasters is not that engineers should not design new bridges or buildings, nor is it that people should refrain from using them. Both such lessons would suffer from the hot-stove effect. However, the real lesson is to understand and learn from the failure and design better structures in the future.

Similarly, the initial stages of conceiving and developing an innovation contain a great deal of uncertainty where failures are inevitable. David Kelley, founder of IDEO, one of the most successful design companies, encourages employees to, “Fail early and fail often.”22 Doing so presents many opportunities for learning; doing so late may be fatal. For example, in the research towards developing the multibillion-dollar drug Lipitor to treat high cholesterol, the research team led by Roger Newton encountered four failures in a row. The management of Lipitor had had enough and wanted to call off the research. However, Newton argued strongly to persist with the research. Like Twain's cat, management reacted superficially to the failures and saw research as going down a blind alley. However, Newton learned from the failures: he acquired a deeper understanding of cholesterol treatment and saw more clearly what specific features the new drug should contain and where to look in terms of drugs that could provide those features. Lipitor went on to become the most profitable drug as of 2012—but Newton went on to lose his job because of management's displeasure with his persistence (see Chapter 7).

The Expectations Effect: Hope Versus Reality

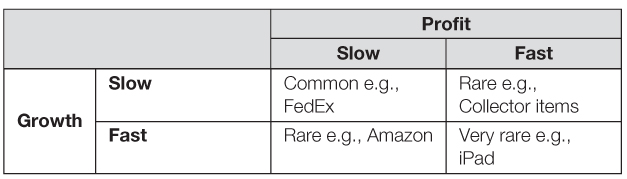

Expectations about innovations tend to be higher than reality for two reasons. First, once people start on the project, they tend to hope for quick results. As Alexander Pope wrote, “Hope springs eternal in the human breast.” Second, involvement in a project leads the innovator to overcount its positives and undercount its negatives. These two biases lead to expectations that may rise beyond reality. These expectations are most pertinent along two dimensions, sales and profits. On each of these dimensions, returns from innovations may be slow or fast (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 Payoff to Radical Innovations

What distribution of growth and profits can firms expect for their innovation? How often does a firm get rapid sales? Rapid profits?

My experience and research suggest that the most common outcome is a slow-slow combination.23 That is, both profits and growth are slow in coming. Examples are that of FedEx and Prius described later in this chapter and the iPod discussed in Chapter 7. Sometimes, growth comes fast but profits come slowly. Examples are Amazon and Facebook (described later in this chapter). Even rarer is the occurrence of slow growth and fast profits. The rarest outcome is fast growth and profits. An example is the iPad. However, the recency and popularity of this example may lead innovators into false expectations for their innovations. Patience is essential. Jeff Bezos, founder and CEO of Amazon.com, noted, “The landscape of people who do new things and expect them to be profitable quickly is littered with corpses.”24

For example, some great innovators (Steve Jobs of Apple) have had seeming, immediate success with one radical innovation (iPad took off and was profitable in the first year), slow success with another (iPod took three years to take off), and failure with still others (such as Newton and Rokr). Given this distribution of outcomes, it is difficult to draw sweeping generalizations. But if any generalization is possible, it is that innovators need to be patient with growth especially for radical innovations. Innovators usually also have to be very patient with profits.

However, innovators need not have to be patient for growth in a vacuum. My coauthors and I have developed a hazard model to predict the takeoff in sales of a new product given characteristics of the product, country, launch price, and launch year. A synopsis of how to use this model for prediction is in Chapter 8 and details are in three published articles.25 My coauthors and I have also developed a hazard model to predict the likely time of disruption of one technology by another, given characteristics of the technologies and the market. Again, a synopsis is in Chapter 8 and details are in a published article.26

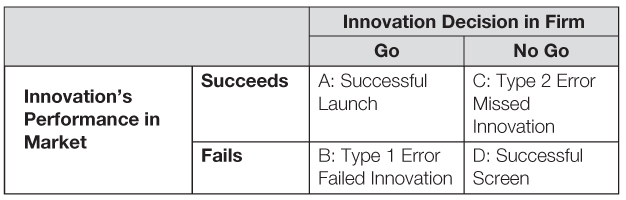

Innovation's Gain-Loss Function: Type 1 and 2 Errors

Any innovation decision involves two types of successes and two types of errors (see Figure 3.1). The two successes are a successful launch and a successful screen. We can call the two errors Type 1 and Type 2. Type 1 error is betting on an innovation that turns out to be a dud or does not really pay off. The loss here is real costs in the development or commercialization of the innovation less any profits that it generated. Type 2 error is failing to adopt or commercialize an innovation that is eventually developed by a rival and turns out to be successful.

Table 3.2 displays the two types of successes and errors. The columns describe the decision that the firm has to make about an innovation, whether to Go or No Go. The rows describes the outcome in the marketplace, whether the innovations succeeds or fails. The crossing of these two factors results in four outcomes: a) a successful launch; b) a failed innovation (or Type 1 error); c) a missed innovation (failure to launch what becomes a successful innovation, or a Type 2 Error); and d) a successful screen of a bad innovation.

Table 3.2 Innovation's Gain-Loss Tradeoff

Type 1 and Type 2 error rates are intrinsically linked by the criteria set to screen for new innovations. As one increases the stringency of the criteria to screen for innovations, Type 1 error rates (failed innovations) drop. But Type 2 errors (missed innovations) go up; that is, the firm fails to introduce some innovations that would have been successful. As the firm decreases the stringency of criteria to screen innovations, the reverse occurs. That is, the firm pursues more innovations, some of which are successful. But doing so also increases Type 1 errors (failed innovations) and decreases Type 2 errors (missed innovations).

The downside to Type 1 errors (failed innovations) tends to be finite. However, the upside of a highly successful innovation is huge. Innovations have changed entire markets, propelled small outsiders into market leaders, and created enormous wealth to the firms that introduces them. Thus, the costs of Type 2 errors (missed opportunities) are huge.

The three effects described above (reflection, hot-stove, or expectations effects) may cause incumbents to pay too much attention to Type 1 errors and their costs. In contrast, incumbents may not pay enough attention to Type 2 errors and their costs. Type 1 errors are visible and involve immediate, tangible costs; thus incumbents may tend to minimize these errors by setting stringent criteria for screening innovations. Type 2 errors often are in the remote future and involve invisible opportunity costs; incumbents may underestimate and tolerate them until it is too late to remedy the situation.

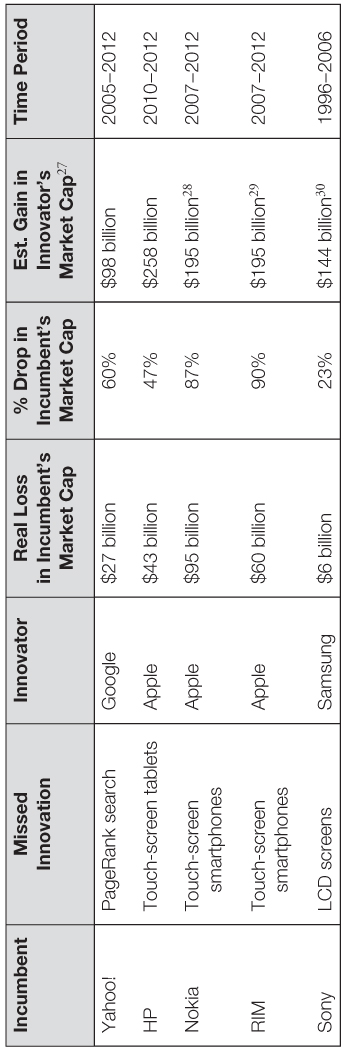

For example, consider the following declines in market capitalization of some leading incumbents as relevant innovations marketed by a rival took off. Nokia, a leader in mobile phones, lost $95 billion in market cap between 2007 and 2012, as Apple's touch-screen iPhone took off. Similarly RIM, a leader in smartphones, lost $60 billion in market cap between 2007 and 2012 as Apple's touch screen iPhone took off. HP lost $43 billion in market cap between 2010 and 2012 as Apple's iPad took off. Sony lost $6 billion between 1995 and 2006 as Samsung's LCD TVs took off. Yahoo!, a one-time leader in Internet search, lost $27 billion as Google's search took off. Moreover, in each of these cases, the firm that introduced the innovation had gains in market capitalization in the billions of dollars (see Table 3.3).

Table 3.3 Real and Opportunity Costs from Type 2 Errors (Missed Opportunities)

Critics may quibble about the details of these examples. In particular, the gain in the innovator's market cap could be due to multiple other innovations that were introduced. But the broad lesson from these examples is that missed innovations involve two losses: the gain in market cap that goes to a rival (that introduced the innovation) and the drop in market cap from an incumbent that failed to innovate. Each of these losses can be huge.

Because these two losses are not easily measured, incumbents may tend to make larger Type 2 errors than is optimal in the quest to reduce visible Type 1 errors. Cognizant of Sony's many missed opportunities in mobile music, smartphones, LCD monitors, and tablets, Masahiro Fujita, president of Sony's System Technologies Laboratories and its Chief Distinguished Researcher, says of risk, “the risk of not innovating is greater than the risk of innovating.”31 What he probably meant is that Type 2 Errors are greater than Type 1 Errors. Thus, a full understanding of risk in innovation must take into account both Type 1 and Type 2 errors.

This discussion also suggests another way to look at innovations. The firm can consider innovations as an option on future growth and profitability.32 Investing in each innovation and each stage of innovation is really buying an option on a future growth market whose full potential is not well known in the present. A firm may need to buy a large number of these options. Most of them would result in a failure with little or no return. But one option out of many may result in a big payoff. The investment is relatively small, tangible, and current. The payoff is in the future, quite rare, but huge.

Estimating the payoff from a future radical innovation involves a great deal of uncertainty, both in timing and size of payoff. As noted earlier, with various coauthors, I have done extensive work on trying to predict the timing of the takeoff of new products and the timing of the disruption from new technologies, and thus reduce uncertainty (see Chapter 8).

Firms do not have to wait for future payoffs entirely in a vacuum. Publicly traded firms have a means of gauging what these payoffs may be by how their stock price responds to announcements about various events in an innovation project (see Chapter 8 for details). From a large-scale study of responses to such announcements, Ashish Sood of Emory University and I found the following patterns:33

Thus, contrary to popular misconception, the stock market does react negatively to announcements about investment in research, even if such investments involve large outlays of funds many years before fruition. Publicly traded firms can use such analyses to get an early indication of how the stock market views their investments in innovation at every stage of an innovation project and thus an idea of what the likely payoff may be.

Case Histories

The subsequent case histories of the origins and struggles of some radical innovators emphasize the need for understanding the gain-loss function and being patient for growth and profits. The four case histories also illustrate different aspects of embracing risk for innovation. Toyota shows the risk of pursuing an embryonic market with no certainty of growth or profit. Amazon shows the risk involved with the need for rapid growth and slow profit. Federal Express shows the risk involved with needing to start on a large scale with a huge investment. Facebook shows the risk involved in holding off against short-term gains to realize a vision. All the examples reiterate the importance of understanding and embracing risk in order to make a success of an innovation.

Three of the four examples show that the founder took the big risk—initially with forming the start-up, and subsequent risks through its growth. This observation reinforces the lesson of the reflection effect, that start-ups or firms that are led as start-ups have a higher propensity to risk than do incumbents.

Gambling on an Embryonic Market: Toyota's Prius

In 2008, Toyota snatched the leadership from General Motors as the world's biggest car manufacturer. Among all Toyota's car models, the snazzy and environmentally friendly Prius is Toyota's flagship of innovation. Since its launch in 1997 until mid-2012, Prius sold over 2.5 million units worldwide, with about half of them in North America.34 It brought back numerous trophies, including the prestigious awards of “Fortune Magazine 25 Best Products of the Year” and “North American Car of the Year.” The Prius had become a powerful “social statement” and an “object of cult-like affection.”35 Despite its global recall woes and the 2011 tsunami in Japan, Toyota's Prius retained its status as the best-selling car in Japan for the third straight year.36 In many respects, the Prius has become a symbol of innovation in automobiles.

However, Toyota's image as a technological innovator and responsible corporate citizen had not always been so. On the contrary, before its success with the Prius, Toyota was seen as a “fast follower,” “a copycat,” and a stodgy, “risk-averse company” with a rigid system of seniority and hierarchy. It seemed to outdo its competitors only through its lean production system. Indeed, Toyota depicted itself as the Japanese “Volkswagen,” trying to appeal to its customers with its affordability and down-to-earth style. The “birth of the Prius,” therefore, was revolutionary not only for its hybrid technology but also for its repositioning of Toyota from a backward, risk-averse company to an innovative risk embracer.37 Every stage of the development, from sketching the model to post-commercialization, involved risk. So how did a company known for careful risk-averse moves gain respect for rapid, risky innovation?

Initial Stage: Striving for Kakushin (“Rapid Innovation”)—Aim High

The idea of the Prius dates back to 1993. That year, the Clinton administration founded Partnership for the Next Generation of Vehicles, a ten-year project in which the federal or state governments would fund research to develop family-sized vehicles that could deliver 80 mpg—three times the fuel efficiency of the normal sedan at the time.38 The Partnership invited all American automotive companies to participate. Despite the unfriendly exclusion, Toyota, discerning that soaring oil prices and a growing middle class would create a demand for a more fuel-efficient vehicle, secretly started a project of its own, known as the G21 (for global twenty-first century).

But no one at Toyota knew what the team was aiming for or how much financial resources the project would take. “I was trying to come up with the future direction of the company,” said Katsuaki Watanabe, then head of corporate planning, “but I didn't have a very specific idea about the vehicle.”39

The engineering team initially targeted to create better fuel economy by refining its existing engine and transmission systems. With its popular and fuel-efficient model Corolla E110 running at 30 mpg, the engineering team aimed to boost fuel efficiency by 50% to 47.5 miles per gallon.40 But that was not audacious enough for Akihiro Wada, executive vice president of Toyota. “Don't settle for anything less than a 100% improvement,” he told his team, “otherwise competitors would catch up quickly.”41 Japanese cars were commonly known as “econoboxes”; such a label would not be fitting for the caliber of the avant-garde vehicle that Wada envisioned. He wanted the new car not only to change Toyota's image as an efficient copycat, but also revolutionize the way the world looks at the Japanese car industry.

Eager for a breakthrough, Wada turned his attention to the hybrid technology, a system that would lower petrol consumption by combining the conventional internal combustion engine with an electric motor. Although the idea of mass-produced hybrids was new, the concept of the engineering system itself was not. In the early automotive history, cars powered by electric motors, steam, and internal-combustion engines all had a competitive share of the market. When American engineer H. Piper invented a petrol-electric hybrid engine that could achieve the thrilling speed of 25 mph in 1905, hybrid cars became the leader of the market.42 However, competitors came up with cheaper and simpler gas-fueled vehicles just a few years later, which killed the hybrid soon after. The idea of a hybrid system was not brought back until the 1970s, when the oil crisis created a demand for more fuel-efficient or even entirely fuel-independent cars. Major carmakers such as Toyota and Honda began to dabble with the hybrid system.

Indeed, Masatami Takimoto, then an executive vice president of Toyota, who was developing a hybrid minivan at the time. That project, however, was hampered by the separation between engineers and sales executives. “Engineers had the firm belief that the hybrid was the answer to all those questions—oil depletion, emissions, and the long-term future of the automobile society—but the business people weren't in agreement,” said Takimoto.43 It came as no surprise that Wada's suggestion of developing a hybrid vehicle came under fire from sales executives and investors alike. Some attacked the idea as an impossible task; others argued that even if Toyota brought the hybrid vehicle to life, the vehicle's profit would not be able to make up its astronomical cost. Despite vehement opposition, Wada went ahead with the risky investment.

Once Wada had set his heart on the hybrid, he wanted it fast, lest his competitors release a similar model before he did and humiliate Toyota for being a “copycat.” Wada gave a twelve-month deadline to his team, scheduling the release of the prototype at the 1995 Tokyo Motor Show, which he believed would be the best showcase for the new car. Though many engineers thought Wada was demanding too much at the time, they nevertheless made the deadline and unveiled the world's first hybrid concept car in October 1995.44 It was aptly named “Prius,” the Latin word for “prior” or “before,” signifying its vision and leadership in innovation. But a greater mission lay ahead—turning the concept into reality.

Experimentation—Undaunted by Failure

While the neighborhood of Tsutsumi was still in a festive mood following the Prius' introduction, Hiroshi Okuda, the ebullient new president of Toyota, received an unwelcome phone call from his engineering team: the engine would not start.

Okuda was concerned. He had just boasted about Toyota's revolutionary development of a hybrid engine at the Tokyo Motor Show. Since 1993, the company had spent 1 billion dollars on the development of the hybrid. He was anticipating the final product to be released by December 1997, giving the team only two years—two-thirds the time for a conventional vehicle. Now the vehicle was not starting. What should he do?

Project failure looms large in the automotive industry, especially during initial development. Facing the skeptical eyes of sales executives and the pressure from Toyota's shareholders, Okuda decided to persist. How could he possibly tarnish Toyota's respect from the world and also Japanese pride? The Prius was a project that he could not afford to let fail.

Determined to succeed, the Prius team designed unrelenting experiments. “On the computer, the hybrid power system worked very well,” said Satoshi Ogiso, the team's chief powertrain engineer, “but simulation is different from seeing if the actual part can work.”45 Even when the team finally fixed the software and electrical problems the car moved only a few hundred yards. The battery continued to fail due to extreme fluctuations in temperature. During the Prius's road test with the executives, a team member had to sit with a laptop to prevent the temperature from soaring.46 To find the right hybrid system, the team went through 80 alternative hybrid engine technologies and 20 different suspension systems before focusing on four designs, which were then refined in extensive detail.47 Although a thousand Toyota engineers were racing day and night to fix the problems, the team still found itself running short of time. “Ordinarily we get two to three months to make sketches and prepare models,” said designer Erwin Lui, “for Prius we got two to three weeks.”48

Despite facing unceasing technological difficulties, Okuda continued to press on with the Prius. Some analysts estimated that Toyota had invested more than $1 billion on the power controller alone.49 If you consider this gamble, then few projects can match the stakes of the Prius. With patience and persistence, the team eventually cleared the obstacles. It added a radiator to an electronic component to prevent overheating; it installed a redesigned semiconductor to keep the vehicle from breaking down.50

Finally in October 1997, Toyota unveiled its first-generation Prius, two months ahead of schedule. Its performance? It logged an impressive 66 miles per gallon—the 100% improvement Wada had targeted.51

Slow Takeoff—A Testament of Toyota's Faith and Patience

Just as Okuda could finally take a breather after the successful development of the Prius, a new challenge lay ahead. Commercialization of the car proved to be just as difficult as its development. Despite the Prius's unprecedented achievement—the first serious competitor to the internal combustion engine since the early 1900s—not everyone was enthusiastic about the invention. Sales managers in the United States were extremely skeptical. They weren't sure if the Prius was really a car. Uncertain that a better fuel economy could attract consumers at the premium price, they wondered if having both the Prius and the Corolla in their lineup would necessitate selling the former at a loss.

In fact, marketing research supported the sales executives' skepticism. Chrysler Corporation's research showed that fuel economy ranked 19th among reasons to buy a car, right after “quality of the air-conditioning.”52 Skepticism and unfamiliarity of the hybrid's technology frightened consumers: when the Japanese government sponsored a festival for people to try out these vehicles on a rainy weekend, many people declined the offer in fear that the electric car would electrocute them.53 “It's difficult to build consumer technology awareness,” said Chris Hostetter, then vice president of advanced-product strategy. “Consumers would have to be taught that the car didn't come with an extension cord. Dealers would have to be trained on how to sell the car and service it.”54 When Toyota invited people in Orange County to try out the Prius, unfavorable reviews soared. Drivers complained about the feel of the brakes, the cheap interior look, and its small. “It was a Japan car,” said Bill Reinert, national manager of advanced-technology vehicles, “and it seemed out of context in the U.S.”55

Initial sales statistics proved the sales managers right. Although the Prius enjoyed some encouraging reception at its launch in Japan, its prospect in the United States was dismal. When the Prius entered the United States in July 2000, oil and gasoline prices hit a record low in the United States. Worse, although the Prius was the first hybrid car introduced in the world, Honda's hybrid, the Insight, reached the U.S. market first. Due to competition from its major rival and low demand, Toyota had to sell the car at a loss, pricing it at $19,995, two-thirds the production cost.56 It initially lost between $10,000 and $16,000 per car, amounting to about a $100 million loss per year.57 With scant volume and low profit, Toyota could hardly afford to advertise the car. The marketing of the car was based mostly on word of mouth, public relations, and the Internet. Foreseeing a gloomy start for the hybrid, the U.S. sales team drafted a contingency plan of issuing cut-rate leases, rental coupons, free maintenance, and roadside assistance to boost sales.58

As a comparison, GM's first hybrid model, the EV1, incurred a loss of between $1,000 and $2,000 per car after its launch in the United States in 1996. GM eventually withdrew the model from the market seven years later, in 2003, due to its heavy losses.59 With the EV1 as its precedent, no one knew how long the Prius could stand in the market before it drained Toyota's financial resources. Toyota was risking big.

Eventual Success

Toyota's patience and persistence eventually paid off. As the wave of environmentalism and green energy in the United States continued to grow, the Prius eventually caught on. The company finally began making a profit on the current third-generation Prius, no less than ten years after its initial launch in the United States.60 The eco-friendly car became the new fashion statement. The purchase of the Prius by celebrities such as Leonardo DiCaprio and Cameron Diaz made the car an overnight sensation. A survey conducted by CNW Marketing Research of Bandon, Oregon, in 2007 shows that about half of the Prius owners said they bought the Prius because the car “makes a statement about me” rather than because they were concerned about “lower emission.”61 Built from the ground up as a hybrid, the Prius's distinct design enabled it to outperform its hybrid competitors, such as Honda Civic, Ford Escape, and Saturn Vue, whose appearances were almost indistinguishable from their gas-guzzling counterparts.

Corporations were quick to take part in the Prius hype. Bank of America launched an environmental program that would subsidize its employees $3,000 for a purchase of a new Prius. More than 185,000 Bank of America employees were eligible for this program.62 Farmers Insurance Group offered up to 10% of insurance discount to customers with a hybrid car. Hyperion, a software company, committed over $1 million a year toward its hybrid purchase initiative that would offer its employees $5,000 for each purchase of a hybrid.63 Godfrey Sullivan, CEO of Hyperion, believed that the message that the program delivered outweighed the cost: “We are not necessarily going to change the world through this initiative, but it's our aim at Hyperion to get people thinking about change, about making a difference.”64

Facing the outcry for environmental protection and CO2 emission reduction, governments worldwide offered various incentives to encourage the sale of the hybrid car. In an effort to promote green energy and boost consumption, Obama's stimulus program, “Cash for Clunkers,” offered buyers a rebate of as much as $4,000 on the purchase of the Prius. That promotion tripled sales of the model.65 While Los Angeles and San Jose, California, exempted hybrid owners from high-occupancy vehicle lane restrictions and street parking fees, Prius drivers in New York State got the special “E-Z pass” that would give them 10% discount on tolls for using the New York Thruway System.66 In the United Kingdom, hybrid owners had to pay only £15 a year for road tax and £10 to register for an annual exemption from the £8 daily London congestion charge (£1 is about $1.6).67 In the Netherlands, companies that own the Prius paid only 14% of car tax as opposed to the regular 25%.68 Pride of ownership combined with its short supply made the Prius a much sought-after item on the market. The Prius retained 57% of its value after three years and only 2% of buyers opted to lease.69 In 2010, the Prius had the best resale value of all hybrid cars.70 The numerous awards that the Prius has won are testimonies to its success (see Table 3.4).71 However, the glory of success can easily mask the long road, the numerous obstacles, the tough marketing, and the great risk that developers of the Prius endured.

Table 3.4 Awards for Prius

| 2003 | “Business Leader of the Year” Scientific American |

| 2004 | “Car of the Year” Motor Trend |

| 2004 | “Ten Best List” Car and Driver |

| 2004 | “North American Car of the Year” |

| 2004 | “International Engine of the Year” |

| 2004 | “Best Engineered Vehicle” |

| 2005 | “European Car of the Year” |

| 2006 | EnerGuide Award |

| 2006 | Intellichoice Best Overall Value of the Year for Mid-Size Cars |

| 2007 | Intellichoice Best in Class Winner: Best Retained Value, Lowest Fuel, Lowest Operating Costs, Lowest Ownership Costs |

| 2008 | “Green Engine of the Year” |

| 2009 | “Most Dependable Compact Car” JD Power & Associates |

| 2010 | “Best Vehicle of the Year” MotorWeek |

Gambling on Growth: Amazon.com

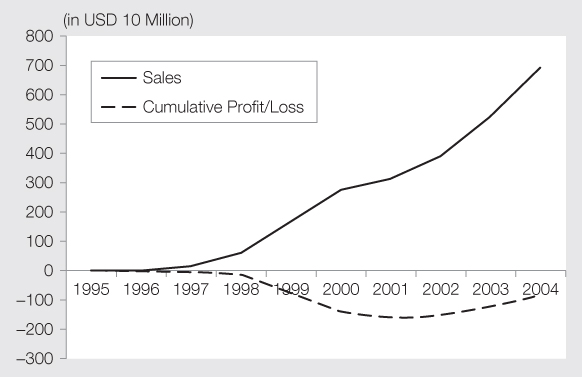

In 2010, Amazon seemed like a tremendous success story. This case is based primarily on research in Gerard J. Tellis and Peter Golder, Will and Vision: How Latecomers Grow to Dominate Markets (New York: McGraw-Hill. 2001). Beginning as a start-up in 1994, it has grown rapidly to a huge corporation. By early 2010 it had sales of $9.5 billion, gross profits of $2 billion, and a market capitalization of $69 billion, much larger than Sony and 69 times the size of the leading brick-and-mortar bookstore, Barnes and Noble.72 How did Amazon.com achieve this amazing success? What is its secret to success? In brief, the answer would be: growing rapidly by fully satisfying shoppers and innovating in every facet of the business to do so. However, achieving these goals required massive investments while tolerating repeated losses. Indeed, the company's innovations and investments kept incurring losses all the way from its founding until 2004, when it posted its first profitable year.73

Nick Hanauer, an early investor in the company, said of this strategy, “What few people understood was that the reason that they [we, Amazon.com,] didn't make money was that for the previous five years every time there was a trade-off between making more money or growing faster, we grew faster. It wasn't that there weren't lots of opportunities to make money. It was just that we had consciously foregone those opportunities to reach scale and make it impossible to duplicate what we had done.”74 But growth was not an end in itself. The overriding goal of the company was to make the customer's experience of purchasing through Amazon.com as complete and satisfying as possible. Jeff Bezos sums up this goal very well, “The better you can make your customer experience …the more customers you'll attract, the larger share of that household's purchases you will attract. You can become a bigger part of a customer's life by just simply doing a better job for them. It's a very, very simple-minded approach.”75

Amazon.com was not the first Web bookstore.76 What made the company unique was Bezos's philosophy, summed up in his own words above, and his effort in achieving it through innovations and investments while sacrificing immediate profits. A review of Amazon's history describes the dedication with which founder and CEO Bezos implemented this strategy. From the very beginning his priority was to make the customer's experience as enjoyable as possible by assuring a wide selection (of books), low prices, speedy delivery, and guaranteeing satisfaction. He stated, “I think the main thing that has differentiated Amazon.com from conventional retailers is its obsessive/compulsive focus on the end-to-end customer experience. That includes having the right products, the right selection, and low prices.”77 Bezos incorporated the company in 1994 and launched the Web site in 1995.

Jeff Bezos first got the idea of an Internet bookstore when doing research as a vice president for D. E. Shaw & Company in New York. He came to the conclusion that books would be a good item to sell online because of the then rapid growth of the Internet (2300%) and the massive inventory returns in the current distribution system (34%).78 He then put his thinking into deeds by deciding to abandon his current profession and start up an online bookstore. David Shaw, the company's founder, asked him to reconsider his plan to leave the security of a generous salary and the status of vice president. However, Bezos was unafraid of the risk, as he told Time, “I knew that when I was 80 there was no chance that I would regret having walked away from my 1994 Wall Street bonus in the middle of the year.… But I did think there was a chance that I might regret significantly not participating in this thing called the Internet that I believed passionately in. I also knew that if I tried and failed I would not regret that.”79

Innovations were central to the success of Amazon.com. For this purpose, Bezos hired the most talented employees he could identify and challenged them to high standards of performance. Employees' creative abilities were an important criterion for recruiting. Says Bezos, “People here like to invent and as a result other people who like to invent are attracted here. And people who don't like to invent are uncomfortable here. So it's self-reinforcing.”80 Bezos supported a “Just Do It” program which rewarded employees for developing and implementing innovations even without the permission of their bosses.81 One of his earliest innovations was owning and operating large warehouses to inventory the books (and later other products) that he sold. Subsequently, the company innovated by relying on other suppliers' warehouses. One of the early innovations that greatly facilitated customer satisfaction with the website was one-click buying. Amazon.com has the patent for this innovation,82 though it is widely copied in one form or another by other websites.

Another major innovation of the company was enabling readers' reviews and ratings of books (that was later extended to other products). This feature created a growing body of user-generated content on each product, which was convenient to use, relevant to the customer base, and always current. Having readers rate the reviews facilitated ordering of reviews by rank and usefulness, adding further value to this feature. This feature created one of the first online communities. A related innovation was the ranking of each book or product on Amazon sales. This innovation was another community feature that gave a direct measure of popularity and indirectly, a crude measure of quality. Scott Lipsky, a former Amazon executive said, “Amazon was probably the first truly worldwide community that was built online. They happened to sell books. But the simple fact that everyone was sharing their thoughts and book reviews made it a community unto itself.”83 A continuous stream of innovations was the company's offering of other consumer products on the same website. Initially it was CDs and movies, then toys, electronics, video games, software, and home improvement. Later they added apparel, sports, outdoors, and gourmet food. More radical innovations were the diversification into auctions and co-vendors of merchandise.

Perhaps the most radical, recent innovation has been the introduction of its own product, the Kindle, an electronic reader. The risks of doing so were twofold: Amazon was a service company, not a hardware company. Moving away from its expertise was a huge risk. Also, success of the Kindle ran the risk of cannibalizing its primary business—print books. Nevertheless, Amazon not only moved ahead, but did so by launching versions of the Kindle at a fraction of the price of rival models. The lowest price was $79 as of 2011. The highest-priced version, Kindle Fire, was $300 less than the lowest priced iPad and sold at a loss. However, sales of Kindle books justified the bold and risky strategy.

Thus, Amazon's success grew from its unrelenting and highly risky innovation. These innovations made the site a one-stop shop for consumers and provided them with a complete and satisfying experience.

Bezos originally forecast profitability in the second or third year.84 However, introducing all these innovations and especially extending into all these product categories was an investment-intense undertaking. The company did everything on a large scale. As such, investments had to be huge. In the first few years, there were no profits to show. The company kept growing by borrowing or selling equity for investments while steadily increasing the size and riskiness of the enterprise. Bezos started the company in 1994 with an investment of $50,000 from his savings. The following year, he persuaded his parents to invest $250,000 from their savings. Sales for the first year were good at $511,000. However, due to marketing expenses, product development, and other expenses, the company had a loss of $303,000.85

Still Bezos decided to increase and not decrease the scale of operation. In 1996, he raised $8 million from KPCB for a 12% share of the equity in the company. However, he invested about $6 million in marketing and $2 million in product development for a massive loss of $ $5.8 million despite revenues of $16 million. All these losses were not accidental. The company's prospectus for the 1997 IPO stated quite clearly, “The Company believes that it will incur substantial operating losses for the foreseeable future and that the rate at which losses will be incurred will increase significantly from current levels.”86

In 1997, Bezos had two figures to be proud of. He raised $45 million through an IPO and reached sales of $148 million. However, he spent $40 million in marketing and $13 million in product development, in addition to other costs of goods and distribution, so that he had another losing year with losses totaling $28 million.87 That year Barnes and Noble entered the online business with lower prices than Amazon. Bezos decided to fight the competition head-on and not be outdone in prices, even at the cost of further losses. His letter to the shareholders outlined his philosophy, “We will continue to make investment decisions in light of long-term market leadership considerations rather than short-term profitability considerations or short-term Wall Street reactions.… We will make bold rather than timid investment decisions where we see sufficient probability of gaining market leadership advantages.”88

In the next two years, Bezos continued to build the business aggressively, growing sales to $610 million in 1998 (growth of 313% over 1997) and $10 billion in 1999. This growth involved massive levels of borrowing and investing in marketing, product development, and warehousing to support this level of rapid growth. However, due to aggressive marketing, sales, pricing, and product strategies, losses grew to $125 million in 1998, a 346% increase over 1997. This pattern of growth continued in 1999, with sales reaching $294 million and losses amounting to $36 million.

In subsequent years, the company still did not have profits, while it came under tremendous pressure to do so. Analysts criticized the strategy of growth without profits, believing that “Amazon's Get-Big-Fast strategy was doomed.”89 Things took a turn for the worse with the bust in Internet stocks in 2000 and the ensuing recession. The worst year was 2001, when Amazon.com showed a total loss of $1.4 billion for the year. The company began many cost-cutting measures, including layoffs and trimming product offerings. However, innovations did not stop. The situation began to improve slowly and subsequently Amazon.com posted its first profitable year in 2004 (see Figure 3.2). Although the company again became the butt of jokes when the stock market crashed in 2008 and 2009, it had a quick turnaround toward the end of 2009 and early 2010.

Figure 3.2 Amazon's Losses Relative to Sales Over Time

In hindsight, Amazon's story is one of amazing growth and success. Beneath the surface, that initial growth and subsequent profit were bought with massive, risky investments in marketing, product development, and warehousing. The road to success was rocky. Bezos showed tremendous courage and undertook huge risks to realize his vision for the company.

Gambling on Vision: Facebook

Since its origins in 2004, Facebook grew in six years to become the second most visited site on the Internet. That success is due primarily to a continuous stream of innovations introduced under constant risk. The risk arose from internal pressure about the dangers of those innovations and external pressure to sell out to venture capitalists and other buyers for a quick gain. At times the founder, Mark Zuckerberg, almost caved in. But he ultimately resisted all those pressures to realize his vision of a transparent, open, and highly accessible social networking site. A brief review of the rise of Facebook reveals the many tough tradeoffs Zuckerberg regularly faced.

Hatch of an Idea in a Dorm Room

One October in 2003, Mark Zuckerberg, a sophomore in computer science at Harvard, thought up a nifty idea.90 He compiled ID photos of his fellow residents by hacking into nine Harvard Houses' online face books. With these photos he created a website called Facemash, where viewers can vote for the hotter of two randomly chosen photos or rate the looks of students in a particular House against other residents. Within four hours, 450 students visited the site and voted at least 22,000 times.91 The site lived for only a few days before students' outrage over the site's privacy violation compelled Zuckerberg to shut it down. Zuckerberg was almost expelled from Harvard for his unauthorized access of the school's network. Nevertheless, the unexpected success of Facemash validated the popularity of such networks and prompted him to start his next project—The Facebook.

At the time, Harvard did not have a student directory with photos.92 “Everyone's been talking a lot about a universal face book within Harvard,” Zuckerberg said. “I think it's kind of silly that it would take the University a couple of years to get around to it. I can do it better than they can, and I can do it in a week.”93 A son of a dentist in New York, Zuckerberg displayed his talent in computer programming at an early age. As a high school senior in Phillips Exeter Academy, Zuckerberg and his friend Adam D'Angelo built a plug-in for the MP3 player Winamp that would customize users' playlists based on their listening habits, much like today's radio site Pandora.94 They offered the service online for free, attracting thousands of users and catching the attention of AOL and Microsoft, which both offered them a job. However, Zuckerberg and D'Angelo opted for colleges.95

Indeed, Zuckerberg coded thefacebook.com in a week and launched the site on February 4, 2004. Within 24 hours, twelve hundred Harvard students had signed up and it took only two weeks for it to reach half of the Harvard student body.96 Zuckerberg's roommates, Dustin Moskovitz and Chris Hughes, soon joined in to help Zuckerberg add features such as “poking”—a flirtatious alert to attract a recipient's attention. They paid $85 a month to a Web-hosting company to maintain the service free to Harvard students. However, the infectious appeal of the site soon exceeded the host's limit. By May, Zuckerberg had expanded the network to more than thirty elite schools. Banner ads had generated a few thousand dollars to the project.97

But that still would not sustain Facebook's rapid growth. (It was then known as thefacebook.com. The company later purchased the shorter domain name facebook.com for $200,000). Knowing Facebook's need for funds, a well-connected classmate of Zuckerberg introduced him to several financiers in Manhattan, one of whom offered $10 million on the spot for the site.98 Such an offer would be tempting for any 20-year-old college student whose website was only four months old, yet Zuckerberg was willing to forego this quick gain to gamble on something bigger. He headed to Silicon Valley that summer to put his ideas to a test.99

Bet on Silicon Valley

“We just wanted to go to California for the summer,” recalled Zuckerberg, perhaps masking the uncertainty and hope in the move.100

Zuckerberg, Moskovitz, and Hughes arrived with no car, no job, and no connection. They sublet a four-bedroom house as an office and bunkhouse.101 As Facebook's exponential growth necessitated more servers, the team found itself in a dire financial situation. Zuckerberg spent his savings of about $20,000 in the first few weeks in Palo Alto.102 But this was far from enough to sustain the site's swelling growth. He risked having to spend more or shutting down and going home.

That was when Sean Parker came into the picture. Parker was the cofounder of Napster and later of Plaxo, an online contacts management network that had raised millions of dollars. Parker was moving out of his apartment to find a new place to stay.103 As he was unloading from his boxes into his white BMW, he bumped into Zuckerberg and his colleagues. Zuckerberg, who had long admired this Internet entrepreneur, asked him to crash in with them.104 So through this accidental encounter, Parker joined the team. By September, Zuckerberg made Parker the president of Facebook.

Besides providing a decent car and buying alcohol for house parties—since he was the only one in the group over 21—Parker brought in connections and valuable advice during the early stage of Facebook. Parker's prior conflicts with and losses to venture capitalists sensitized Zuckerberg of the risk of losing control of the start-up to gain capital. He was subsequently very wary of venture capitalists. Parker's connection in Silicon Valley brought in the first investor to the company—Peter Thiel, a one-time CEO of PayPal. After Zuckerberg's presentation on Facebook, Thiel agreed to lend $500,000 to the kids in exchange for a 10.2% of the company, leading to a value of $4.9 million.105 Although the valuation was lower than what Zuckerberg had previously got in Manhattan, he appreciated how Thiel, unlike other venture capitalists, trusted him with complete control over the young company.

As the 2004 fall semester approached, Facebook continued to grow, doubling its membership to 200,000. Zuckerberg now faced a life-changing dilemma. He had just secured funds of $500,000 and a foothold in Silicon Valley. To sustain Facebook's growth, he needed greater commitment and funds. Should he continue the risky summer project in Silicon Valley or go back to school to earn a secure degree?106 Many of his colleagues wondered if Facebook was merely a fad and questioned whether this dorm project was worthy enough a cause to drop out of school. Despite the risk, Zuckerberg gave up the security for his dream, aspiring to make real social change through Facebook.

Risk-Loving Hacker Culture

One of the keys to Facebook's rapid expansion was its embrace of risk. Even though the company expanded over time to a point where staffers could no longer tap on each other's shoulder, Zuckerberg kept the company's pipeline short. Its tolerance of failure allowed its engineers to experiment freely and iterate innovations in real time. Zuckerberg encouraged his engineers to move fast, pushing new code to be tested daily: “We think eventually you get judged not by how you look but by what you build. I think there's a lot of pressure inside of companies where people want to optimize for a launch to go smoothly. But really you want to be the best over time. Take more risk. If we do those, we have a good shot of succeeding.”107 Although Facebook, with serious investor support, could no longer operate like a frivolous dorm project, its hacker culture lived on. “What most people think when they hear the word ‘hacker’ is breaking into things,” said Zuckerberg, “but in Facebook, it's about being unafraid to break things in order to make them better.”108

Zuckerberg kept his commitment to small teams where an individual voice could be heard and innovative ideas could be realized quickly through collaboration. He maintained weekly product updates, but if his team desired to test an idea, it could push the code to a group of users daily. To Zuckerberg, hacker culture is the collective effort to build something “bigger, better, and faster” than individuals can do alone. “The root of the hacker mind-set is ‘There's a better way,’” said Paul Buchheit, the developer of Gmail at Google and cofounder of FriendFeed who joined Facebook after it acquired FriendFeed. “Just because people have been doing it the same way since the beginning of time, I'm going to make it better.”109 The risk-loving hacker culture of Facebook indeed manifested itself through rapid deployment of new features. For example, in September 2004, the team added group applications and its idiosyncratic “wall,” a summary page on which you and others could write.110 By December 2004, ten months after its creation, Facebook reached one million users.111

It was soon apparent that Thiel's money would not be enough to sustain Facebook's growth. In May 2005, with the help of Thiel, Zuckerberg raised $12.7 million from Accel Partners, allowing him to expand Facebook's service to more than eight hundred college networks.112 Every expansion was fraught with risks. One risk was in diluting the elitist origins of the network, especially when it expanded beyond the Ivy League. The other risk was of overloading the network with traffic, without any immediate increase in revenues or apparent benefit. Always on the founders' minds was the demise of Friendster, an older, hugely successful network that failed when traffic unbearably slowed down service. Supporting Facebook's expanded traffic required thousands of dollars in new, more powerful servers.

In the summer of 2005, Facebook entertained expanding the network to high school students. This move had several risks. First, there was again the danger of being overwhelmed with traffic. Another potential problem was the negative reaction of college students who would find their network populated with high school kids. Then there was the risk of allowing e-mail addresses that did not have the certainty of identity of college e-mail addresses. In addition, many parents were opposed to their schoolchildren being on Facebook due to the exposure of minors to online predators. Nevertheless, Zuckerberg prevailed in his arguments to expand the network. In September 2005, Facebook included high school students, resulting in 5.5 million active users. The following month, Facebook added a photosharing feature onto the site. That move almost burned down the site's infrastructure due to the exploding technical demand.

Nevertheless, the growing popularity of the site with added features convinced Silicon Valley's venture capitalists to continue investing, allowing Zuckerberg to bring in $27.5 million in April 2006.113 Zuckerberg then increased its users by adding work networks.

In September 2006, Zuckerberg made a highly risky move of opening the site to everyone with a valid e-mail address. Students were not happy with the swarms of people who joined the site. They may have been uncomfortable being friends with parents and relatives from whom they wanted to maintain a separate identity and life. While some students rushed to delete their X-rated party pictures, others joined online petitions threatening to leave Facebook. The expansion, which diluted Facebook's exclusive appeal, risked the site becoming the second MySpace. “I didn't realize it from the outside, but the change in going from a [college-student-only] site to being open to the world was extremely controversial,” said Paul Buchheit. “Most people [at Facebook] thought it was a bad idea and was going to ruin the site.”114 Despite the strong opposition, Zuckerberg persisted on his vision to make the world more transparent, open, and connected. His missionary zeal steered Facebook clear of all hurdles that would derail its growth. Students eventually adapted to the change. Facebook's user numbers skyrocketed.

News Feed Crisis

Zuckerberg's tolerance for risk at times blinded him to Facebook's users' sentiments. The rashness showed up when Facebook introduced News Feed, which broadcasts users' online activities to everyone they have friended on Facebook. This set off a backlash in the Facebook community, particularly college-bound users, who felt that the new feature had intruded upon their privacy, never mind that their eagerness to share their personal information was the mainstay of Facebook's existence. Taking advantage of the new issue-oriented feature—“global groups”—angry users created a group called “Students Against Facebook News Feed,” ironically attracting more than seven hundred thousand users through News Feed (“Your friend has just joined this group”) in less than 48 hours.115 Zuckerberg rushed to install a privacy option three days later that allowed users to control their information flow. “We really messed this one up,” Zuckerberg wrote in his open apology letter.116

The crisis eventually cooled down. Zuckerberg later claimed that News Feed had been the most successful move for the site. “Once people had the controls and knew how to use them, they loved News Feed,” said Zuckerberg.117 The News Feed crisis did not discourage Zuckerberg from taking risks. “Regardless of what we do, if it changes the site, there will be reactions. Change is really disruptive for people, especially if you're providing a web service that people aren't opting into directly,” Zuckerberg said. “Values are worthless unless they're controversial. We want to move quickly. We're willing to give up a huge amount of stuff in order to move quickly.”118

To Sell or Not to Sell

It did not take long for Facebook to whet the media giants' appetite. In fall 2005, just as the site was reaching five million users, Zuckerberg started getting instant messages from Michael Wolf, president of Viacom's MTV network, expressing his interest to meet with Zuckerberg in Palo Alto. In December, Wolf offered Zuckerberg an attractive opportunity to get together while he was visiting in San Francisco. Wolf offered Zuckerberg a ride home to New York for the holidays, in Viacom's corporate jet.119

Zuckerberg fell for the bait. Because Viacom's corporate jet was in fact unavailable, Wolf chartered a first-rated Gulfstream V to take him to the east coast. During the five uninterrupted hours with Zuckerberg aboard, Wolf discreetly suggested his intention to acquire Zuckerberg's firm. But the 21-year-old Zuckerberg maintained a healthy distance, interrogating Wolf about his MTV business instead, with particular interest in advertising.

Finally, before the plane landed, Zuckerberg said, “This plane is amazing!” Wolf took the opportunity and replied: “Maybe you should just sell a piece of the company to us. Then you can have one for yourself.”120

Over the next few months, Wolf continued to pursue Zuckerberg. He made a cash offer of $800 million and provisions that could make it worth as much as $1.5 billion.121 For a small business that was just a year old and involved small investments by the cofounders, this sum must have seemed astronomical.122 Selling the company would solve the site's financial problems, for the site was running at a loss. Zuckerberg, who still lived in his sparsely furnished rented apartment, could take home a handsome sum of money.123 He could cut short the uncertainty and walk away with a sure, huge monetary payoff. But Zuckerberg had an ambitious vision in mind. He wanted to build a comprehensive “social graph” that would revolutionize how people interact with each other. He wanted to change the world. “I don't really need any money,” he told Wolf. “And anyway, I don't think I'm ever going to have an idea this good again.”124

A few months later, Yahoo!'s CEO Terry Semel offered $1 billion in cash to buy Facebook.125 Zuckerberg agonized about the offer, facing intense pressure from cofounders, employees, and board members to accept. Looming over Zuckerberg's decision was the fallen giant that preceded Facebook—Friendster. It was the first social network phenomenon, and it had struggled to manage growth. Friendster ultimately failed—after turning down Google's $30 million offer in 2002 (which, if paid in stock, would have been worth about $1 billion in 2007126). A few weeks later, due to disappointing second quarter earnings, Yahoo! lowered its offer to $850 million. Zuckerberg was relieved and easily turned down the offer with board approval. That night he went out with his colleagues for a beer. The deal was off.127 Paul Buchheit saw Zuckerberg's spurning the Yahoo! offer as a defining moment, “They basically gambled the whole company on that one step.”128

“Can this kid be for real?” asked Ellen McGirt, former editor of Fortune, now a senior editor of Fast Company.129 For those who remember the ambitions crushed and fortunes lost during the dot-com boom, selling the company for a pile of money seemed to be lucrative exit strategy for any young innovator. With founders' sales of start-ups like MySpace to News Corp for $580 million and YouTube to Google for $1.5 billion, many wondered about Zuckerberg's judgment. Zuckerberg, a member of the Google generation, seemed to be too young to have learned from the dot-com bubble.

Moreover, the competition in this market was growing intense with the entry of tech giants. Cisco acquired Five Across, which sold social networking software to corporate clients. Yahoo! built a social networking site called Yahoo! 360. Microsoft jumped into the market with the introduction of Wallop. Google dabbled with the idea of integrating social networking into its e-mail service, known as Buzz. Even Reuters tried to get into the game by developing a social network that targeted fund managers and traders. Could Facebook survive against these corporate giants? The offers from Viacom and Yahoo! seemed like sure, easy money relative to a highly uncertain future.

But Zuckerberg calmly focused on his vision. He was playing a different game. “I am here to build something for the long term,” said Zuckerberg, “Anything else is a distraction.”130 An advisor to Facebook described it this way, “A lot of people say there are problems with having a 22-year-old C.E.O., but one thing that is good about it is that he doesn't remember the boom and the bust that followed. That has distorted the thinking of a lot of people. If they have a good product or service, they sell way too early and they don't stick with it.”131 Indeed, Zuckerberg stayed with the founding motto of the site: openness, transparency, and collaboration. Although many pundits in Silicon Valley deemed this precocious kid naive and foresaw a falling trajectory, Zuckerberg was steadfast with his vision, reluctant to give it away for greenbacks.

Facebook needed to grow quickly to keep itself competitive in the fast-paced Internet world. But it kept running short of funds to support the site's rapid expansion. Then, in the summer of 2007, Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer approached Zuckerberg with a proposal. Zuckerberg knew Ballmer's intent and took him for a walk outside his office in Palo Alto. He told Ballmer that they were raising funds for Facebook's expanding infrastructure at a $15 billion valuation.132 Zuckerberg thought the lofty $15 billion was more than any company of its size could ask for. A moment of silence ensued. But Ballmer had a more ambitious goal. He said, “Why don't we just buy you for $15 billion?”133

Though, Microsoft's offer was fifteen times that of Yahoo!'s, Zuckerberg's response was negative. Zuckerberg, staunchly and naively optimistic as some might argue, would rather risk his site overloading than losing full control of it. Moreover, he was determined to pursue his vision. Ballmer tried to buy the company in stages but Zuckerberg resisted all these moves.134 Ballmer ended up paying $240 million for 1.6% share of the company. That gave Facebook the value of $15 billion, the lofty figure Zuckerberg had lobbed to Ballmer.135

Opening the Site to Third-Party Applications

“Crushing the competition has freed the company to gamble even harder,” wrote reporter Ellen McGirt on describing why Facebook was rated as the most innovative company in 2010.136 In May 2007, Zuckerberg redefined the level of risk for its company by opening the platform to third-party developers, allowing them to take advantage of Facebook's people connections, which grew to 41 million. In just a few months, some 80,000 developers added more than 4,000 new applications.137 What was Facebook's return for hosting the service? None, not a cent! To outsiders, Zuckerberg seemed to be missing out on a big financial potential, but he was just fine with it. He reinforced the principles of hacker culture: “It's good for the ecosystem, good for the product, and good for the users. We want a system where anyone can develop without having our permission. There are things that we will never think of, or get around to, that would really make the user experience better.”138 To encourage developers' involvement in Facebook applications, Zuckerberg even rewarded $25,000 to $250,000 for the most innovative programs. Zuckerberg's vision of openness, transparency, and collaboration has defined social networks in the current age and fueled Facebook's growth.

This vision, however, did not come without risk, and even that is an understatement. “We've had a lot of scalability problems in the past,” D'Angelo said. “If you are not careful, you can overwhelm your engineering team to the point where your servers die and your service fails.”139 As ads were still minimal and outside developers paid no fee to put their applications on the site, many investors were wary about Zuckerberg's lofty vision and his indifference to financial risks. Zuckerberg's response? “In a world that's moving quickly, you know that if you don't change you'll lose. Not taking risk is the riskiest thing you can do. You have to do things that are kind of bold even if they're not obvious.”140

Risk Rewards

On its sixth birthday, Facebook celebrated worldwide users of almost half a billion—that's one in every twelve persons in the world! The three musketeers expanded their team to twelve hundred engineers and their territory to a new 135,000-square-foot office space in Palo Alto. The social site became so viral worldwide that it has been translated into more than seventy languages. In 2008, Collin English Dictionary declared “Facebook” as their “Word of the Year.” The following year, the New Oxford American Dictionary added the verb unfriend, defining it as “to remove someone as a ‘friend’ on a social networking site such as Facebook.” In September 2009, Facebook finally announced that it had turned cash flow positive for the first time, soothing the nerves of some agitated investors.141 In April 2010, Facebook took Google's crown as the most visited website in the United States, accounting for 7.07% of U.S. Web traffic.142 Facebook is supposed to have played an important role in the revolutions and protests in Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Syria, and Russia. Indeed, Facebook is so powerful a social utility that some authoritarian governments, such as China, Syria, Iran, Vietnam, and recently Pakistan, have been blocking the site intermittently to prevent political uprisings. Especially satisfying to the founder must be the voice for millions of people seeking liberation.

Facebook might have a long way to go in reaching real financial success, but its enduring social influence has already manifested itself. This influence was achieved by Zuckerberg's unrelenting innovation with a risk-loving culture that he cultivates inside his company. Had Zuckerberg taken the $10 million from Manhattan six years ago, or the millions and billions offered subsequently, Facebook might never have gone so far. Had Zuckerberg not taken the risk of successively opening the site to new segments of the public, it might have been forgotten by its passionate college students once they graduated. Had Zuckerberg not been unrelenting in innovations, any competing site or Internet giant would have surpassed Facebook in audience. Zuckerberg gave up opportunities of quick gains to achieve his goal to make the world a freer and more connected place.

Gambling on Scale: Federal Express

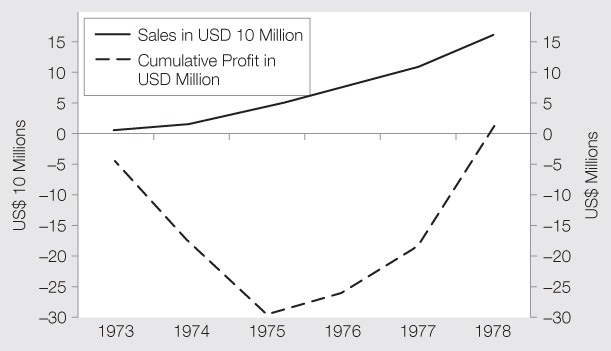

Fred Smith conceived of Federal Express in a now-famous term paper he submitted in a class at Yale in 1966. This case is based primarily on research in Gerard J. Tellis and Peter Golder, Will and Vision: How Latecomers Grow to Dominate Markets (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001) and Robert A. Sigafoos, Absolutely, Positively Overnight! (Memphis, TN: St. Luke's Press, 1983). After a short but successful military service in Vietnam and some work to build up his inherited business, in June 1971, Smith founded Federal Express. In July 1975, the company had its first profitable month. In 1976, the company became the dominant shipper in the small-parcel airfreight business. That was also its first profitable year (see Figure 3.3). From then on, shipments and profits increased rapidly. Despite increasing competition, Fred Smith maintained leadership of the market he started through highly risky but unrelenting innovation.

Figure 3.3 Early Growth of Federal Express