Chapter 1

Why Incumbents Fail

Success is empowering. But success is also enthralling and embeds the seeds of failure.

INCUMBENT FIRMS that dominate their markets often fail to maintain that domination for long, despite all the advantages they enjoy of market leadership. For example, Sony created the market for mobile music with the introduction of the Walkman. Yet, Apple's iPod now dominates that market. Kodak dominated the market for film photography but declined and ultimately went bankrupt as digital photography took off. Barnes and Noble dominated the book market for decades, but Amazon is now the biggest force in book retailing. Intel dominated the market for PC chips, yet is a minor player in the fast-growing market for cell phone and tablet chips. Research in Motion dominated the market for smartphones with their once popular Blackberry. Yet Apple now dominates that market.

Indeed, market leadership frequently passes from firm to firm in many markets. In the market for Internet search engines, leadership passed from Wandex to AltaVista to Overture to Yahoo! to Google. In the microcomputer market, leadership passed from Altair, to Tandy, to Apple, to IBM, to Compaq, to Dell, to HP. Now tablets are threatening HP's leadership. In retailing, market dominance has passed from Sears to Wal-Mart and is now moving toward Amazon. A review of the evolution of markets shows that many firms often do not stay as market leaders for long (see Table 1.1). Moreover, recent research suggests that the duration of market leadership is dropping by as much as half a year, every year!1

Table 1.1 Examples of Multiple Changes in Market Leadership

| Category | Sequential Leaders Separated by Commas |

| Mobile music | Sony, Apple |

| Internet search | Gray's Wandex, AltaVista, Overture, Yahoo!, Google |

| Video games | Magnavox, Atari, Nintendo, Sega, Sony, Microsoft, Nintendo |

| Microcomputers | Altair, Tandy, Apple, IBM, Compaq, Dell, HP |

| Browser | Mosaic, Netscape, Internet Explorer |

| Word processing | IBM, Wang, Easy Writer, WordStar, WordPerfect, Word |

| Light beer | Trommer's, Gablinger's, Brau, Miller, Bud |

Source: Adapted from Tellis and Golder, Will and Vision: How Latecomers Grow to Dominate Markets, New York: McGraw Hill, 2001.

Sometimes, firms not only fall from leadership but completely fail and exit the market. For example, three one-time leaders of the microcomputer market, MITS (owner of Altair), Tandy, and IBM, have since quit the market.

Why do great incumbents stumble, decline, or fail? Professor Peter Golder of Dartmouth College and I studied the origin, growth, and evolution of sixty-six markets spanning up to 150 years.2 Our research strongly suggests that the primary reason for firm failure is a failure to innovate unrelentingly. No barrier to competitive entry provides a permanent protection against the force of innovation. Innovation regularly breaks down barriers, be they in economies of scale, patents, business models, or relationships with buyers and sellers. As a result, there are no permanently dominant firms or permanent market leaders. Perennial success belongs to those firms that innovate unrelentingly.

Then, why do incumbent firms, especially market leaders, fail to innovate unrelentingly?

Why Incumbents Fail to Innovate Unrelentingly

A firm requires a great deal of resources to stay unrelentingly innovative. Incumbent firms have at their disposal more resources, experience, expertise, talent, and cash for innovation than lesser rivals or new entrants. Thus, incumbents are in the best position to stay innovative and dominate their markets. So, a lack of resources is not the reason that incumbents fail. On the contrary, many incumbents fail to innovate even though they are blessed with abundant resources. Ironically, market incumbents fail to innovate unrelentingly even though many, if not all, rose to that position of market dominance by introducing a radical innovation.3 Nonetheless, some incumbents do maintain their leadership for decades.

Why do so some incumbents maintain their dominance while others fail? Professor Rajesh Chandy of London Business School and I sought to address this issue with an in-depth study of ninety-three innovations together with interviews of executives and a survey of about two hundred firms.4 Our research suggests that incumbents fail because they fall victim to the “incumbent's curse”: a self-destructive culture that results from their prior success.

Paradox of the Incumbent's Curse

Many incumbents are at the top of their game because they market a superior product that emerged from a radical innovation. Because of their dominant position, they enjoy high prices, large market share, and strong cash flows. This position imbues them with market power and prestige.

Market dominance does not come easily. It is the fruit of innovation, clever strategies, and effective management over many years—if not decades. But market dominance, power, and success contain the seeds of self-destruction. They lead to three traits that hamper continued innovation and hinder continued leadership.

First, incumbents fear cannibalizing their current successful products. Cannibalizing means letting a new product replace a current product in sales to customers. Incumbents are reluctant to change the status quo and endanger their successful products. When innovations threaten their successful products, market incumbents' immediate reaction is to protect those products that have brought them strength and success. Even though they themselves develop some radical innovations, incumbents are reluctant to commercialize them for fear of jeopardizing their cash flows from successful products. This reluctance arises from some economic and psychological principles. Chapter 2 explains the economics and psychology of this trait.

Second, incumbents are risk averse. They tend to overweight their current successful products relative to risky, uncertain innovations for the future. Leaders measure all new innovations by the speed with which they can yield returns that match up with those from their hugely successful products. This weighting is not illogical. Innovations that create new markets involve huge investments, take a long time to bear fruit, and encounter many failures. Thus, innovations are risky. Incumbents are averse due to three biases in their perception of risks and dealing with failures: the reflection effect, the hot-stove effect, and the expectations effect. Chapter 3 explains these causes of risk aversion.

Third, incumbents focus too much on the present. They channel their efforts to carefully market their current successful products to satisfy current customers. Because of their involvement with the current problems and crises, the present looms large while the future seems distant. Thus, incumbents develop a bias that focuses on the present at the cost of the future, even though the future belongs to innovations rather than to present successful products. The legacy of the past and present becomes a hindrance to embrace the innovations of the future. Chapter 4 explains the psychological biases that cause this emphasis of the present over the future.

Fear of cannibalizing successful products, risk aversion, and focus on the present constitute three roadblocks for commercializing innovations. The strength and success of incumbents, especially market leaders, engender these traits that hamper future innovation and success. Though incumbents ascended by embracing radical innovations, their success creates a self-defeating culture of inertia that hampers commercializing future innovations. We call this the incumbent's curse. It explains the epigram at the start of this chapter, “Success …embeds the seeds of failure.”

Lou Gerstner, the former CEO of IBM who transformed the culture of IBM between 1994 and 2003 and prevented impending demise, comments on this problem: “This codification, this rigor mortis that sets in around values and behaviors, is a problem that is unique to—and often devastating for—successful enterprises …What I think hurt the most was their [successful enterprises'] inability to change highly structured, sophisticated cultures.”5

The following particular examples illustrate this paradox.

Telling Examples

In the late 1970s, Sony created the mobile music market with the launch of the Walkman. Sony's CEO had to push the Walkman to market against intense internal opposition from Sony's engineers and managers (see Chapter 7). Once introduced, the Walkman took off quickly, exceeded the expectations of all its managers, and created a whole new category. Yet when MP3 technology came along, Sony failed to retain dominance of the mobile music market with an easy-to-use MP3 player. Instead, it ceded that market to Apple and its iPod. Ironically, Sony did have an MP3 player before the iPod. However, Sony's MP3 player was not user-friendly partly due to its anti-piracy software. Such software was included in deference to the music business that wanted to protect royalties (see Chapter 2).6 Here again, fear of cannibalizing royalties, a focus on the present, and risk aversion crippled Sony's MP3 player. Sony's huge music library could have been an asset in marketing its MP3 player, but instead became a handicap.

A similar story occurred at Xerox, though on a much larger scale. In the mid-1970s, Xerox had developed in its PARC labs most of the innovations of the modern personal computer generation. These innovations include the Ethernet, the personal computer, the laser printer, PC networking, e-mail, the mouse, graphical user interface (GUI), word processing, the WYSIWYG editor, and object-oriented programming. Xerox was ahead of all competitors in these technologies and was ready to launch the “paperless office,” as envisaged by its late CEO, Joseph Wilson. However, we do not see Xerox's name on any of these products today. The reason is that Xerox's senior managers were too focused on the copying business. They did not see the value in the paperless office and were afraid that these new technologies would cannibalize its copying business.

Though unwilling to put forth newer technologies, Xerox itself sprang up from a radical innovation that incumbents at the time ignored and belittled. In 1935, the lone researcher Chester Carlson developed xerography, or dry copying, in his garage after being dissatisfied with existing alternatives for copying. However, none of the giant firms, including 3M, Kodak, RCA, or IBM, were interested in investing in xerography. In 1944, a small firm called Haloid took up the challenge of developing a copying machine from Carlson's innovation. That quest involved extensive research and development, extreme hardships, great risks, and fifteen years. Haloid's CEO, Wilson, championed the technology and steered Haloid through those tough times. By the end of that road, Haloid had developed the Xerox 914. When commercialized in 1959, the Xerox 914 was a huge success and propelled tiny Haloid to leadership of the copying market, ahead of all the incumbents of its time. Haloid changed its name to Xerox. However, its great success in xerography rendered Xerox short-sighted, risk averse, and fearful of cannibalizing its then successful copying business. Thus, it did not embrace and aggressively commercialize the next frontier of radical innovations in the form of the paperless office, which its own labs developed.

The examples of Sony and Xerox are not isolated but typical examples of roadblocks facing successful companies. Some CEOs of successful companies realize that their own success and indeed their own companies are the greatest threat to future innovations and success. For example, when Google CEO Larry Page was asked what was the greatest threat to Google, he replied in one word, “Google.”7 He had realized the paradox of the incumbent's curse. Ex-CEO Eric Schmidt elaborated, “The problems of Google's scale are always internal. …Large companies are their own worst enemies because internally they know what they should do, but they don't do it.”8 Eric Schmidt's explanation is right on target except for one word. It is not the problem of scale per se, but the incumbent's curse. Success creates large scale but success also creates the incumbent's curse that hinders future innovation and success.

The Preeminence of Culture

How can a firm overcome the incumbent's curse? Our research over two decades strongly suggests that the internal culture of a firm is the most important driver of a firm's innovation.9 The cause of failure and the impediment to success lies not in hard formulae, models, technologies, buildings, or dollars, but in a soft, mushy, difficult-to-grasp, and tough-to-master thing called culture. The importance of culture is tersely summarized again by Lou Gerstner, “I came to see, in my time at IBM, that culture isn't just one aspect of the game—it is the game.”10 The culture at many firms is not fully explicit or written down in rule books. But as Gerstner states, “Still, you can quickly figure out, sometimes within hours of being in a place, what the culture encourages and discourages.”11 In a global survey of the top one thousand firms on the metric of R&D spending, Booz and Company conclude that “Culture Is Key.”12 However, neither of these sources provides a deep understanding of culture.

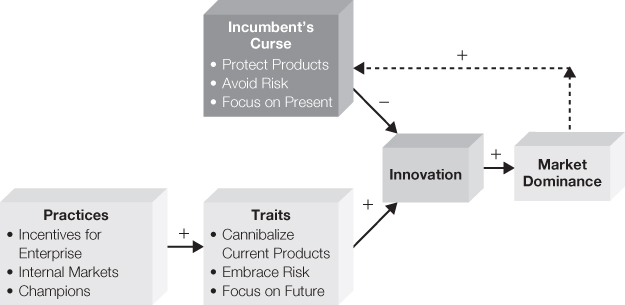

What does culture mean? How does it relate to innovation? Over a period of four years, Rajesh Chandy, Jaideep Prabhu of Cambridge University, and I studied over 770 firms across seventeen countries.13 Our research suggests that a firm's culture is its set of traits or values and practices or traditions that constitute the internal human working environment for employees. In particular, the culture for innovation consists of a parsimonious set of three traits and three practices. The traits are a willingness to cannibalize current (successful) products, embracing risk, and focusing on future markets. These three traits overcome the incumbent's curse. The three practices are empowering innovation champions, providing incentives for enterprise, and fostering internal markets. Figure 1.1 summarizes these cultural components and shows how they relate to each other.

Figure 1.1 Dynamics of Components of Culture of Innovation

Traits are difficult to change. But practices are more amenable to change and can engender the traits. Creating a culture for unrelenting innovation is very tough for large, successful firms because of the incumbent's curse. For example, during his tenure as CEO of Sony, Howard Stringer struggled to change the culture of the company to make it more nimble and innovative. In the end he failed because Sony's culture is highly resistant to change. Commenting on Sony's failure to change and innovate successfully in the 2000s, Howard quipped, “Love affairs with the status quo continue even after the quo has lost its status.”14

In the world today, firms can get funds from their own reserves, angel investors, venture capitalists, banks, or investors at large. Due to relatively efficient financial markets, funds are not hard to get. Once they have these funds, firms can buy tools, land, building, and plants. They can invest in R&D to develop or buy intellectual property including patents. They can hire talent. In other words, given funds, firms can buy equipment, intellectual property, or talent. But they cannot buy culture. Culture is that uniquely human product that is complex, ambiguous, slow to develop, difficult to change, and hard to analyze. Money can't buy culture. And culture plays a critical role in innovation. Thus, carefully understanding what is the culture that helps or hinders innovation is critical to being innovative and dominating markets in the long term.

Chapters 2 to 4 explain in detail the three cultural traits that foster innovation; Chapters 5 to 7 explain the three practices that engender those traits. Here is a preview of each of these traits and practices.

Traits for Innovation

The examples above illustrate the incumbent's curse—success with current products provides a strong motive to sustain the status quo and resist innovation.

The first trait for innovation is a willingness to cannibalize one's own successful products. Incumbents have a high reluctance to cannibalize successful products; small rivals or new entrants have no such inhibitions. For example, the development of paid searched advertising made Google a huge and highly profitable firm in just ten years. However, few people know that Microsoft had a model for paid search advertising before Google. A few of Microsoft's own employees developed a search service with paid ads, called Keywords. However, Microsoft killed the service when it seemed it would cannibalize the banner ad business of MSN.15 In this case, fear of cannibalizing existing products led Microsoft to forego one of the most profitable business opportunities in the last decade.

Chapter 2 explains with examples the importance of a willingness to cannibalize successful products. It explains the economic and psychological factors that cause incumbents to be reluctant to do so. It argues that for many organizations, the challenge is not only generating innovations but embracing them when they cannibalize successful products, even though these innovations arise from a firm's own employees. The chapter also explains the challenge of technological evolution and provides a framework to understand and manage it. Cannibalization is relatively easier when innovations occur in the same platform and market. Cannibalization is toughest when innovations occur in new platforms in new markets; it is greatly facilitated by a focus on the future and a willingness to embrace risk.

The second trait for innovation is embracing risk. The path to a successful innovation is strewn with failures, both before and after commercialization. Failure is endemic to innovation, with rates ranging from 50% to 90% at various stages of development and commercialization. Thus, innovation is a highly risky business. The risk looms especially large if a firm is currently dominant and has a steady stream of cash from a dominant market position. The risk appears lower for a new entrant that has no market to lose. As a result, incumbents prefer a modest but certain payoff over a huge uncertain payoff, even though the latter has a higher expected value. This psychological asymmetry in risk perception is called the reflection effect. Chapter 3 explains this effect and other effects that cause firms to be risk averse. It explains the essential tradeoff inherent in risk: balancing Type One errors (failed innovations) with Type Two errors (missed innovations). Four case histories illustrate these principles in action.

The third trait for innovation is a focus on the future. Success in the current generation of products leads to glorification of the past, preoccupation with the present, and neglect of the future. For example, in the case of mobile music, Sony failed to see the future market in MP3 players because of its involvement in the Walkman and its preoccupation with royalties from songs. Four biases underlie this misplaced focus on the present over the future: hot-hand bias, availability bias, paradigmatic bias, and commitment bias. Chapter 4 explains the psychology of these biases, which cause incumbents to value the present over the future. It describes four tools to foster a focus on the future: predicting underlying technological evolution, predicting takeoff of innovations, targeting future mass markets, and identifying emergent consumers. While none of these tools are infallible, their combined use encourages incumbents to take time off from the present and forces them to think about the future in constructive ways.

Thus, willingness to cannibalize current products, embracing risk, and focusing on the future are three traits that constitute a culture for innovation. However, the traits of an innovative culture do not develop spontaneously within a firm, nor can they be mandated by managerial fiat. On the contrary, they are deeply psychological characteristics that emerge slowly from a firm's practices. Understanding their psychology and economics is a first step toward their adoption. Certain practices foster these traits (Figure 1.1). Moreover, practices are more responsive to managerial dictates than are traits. Thus, although a firm may not be able to change its traits immediately in the short term, it can shape, cultivate, and foster them in the long term by adopting certain practices. What are these practices?

Practices for Innovation

Three practices promote the traits that engender innovation: providing incentives for enterprise, fostering internal markets, and empowering innovation champions. Here is a preview of these traits that are detailed in Chapters 5 through 7.

In successful, dominant firms, incentives are often set to current sales or satisfaction of current customers. What's worse, sometimes incentives may be set for seniority or longevity. Such incentives foster loyalty but not innovation. When incentives are linked to innovation, research shows that they do so in a perverse way: weak rewards for successful innovation but strong penalties for failure.16 The problem of risk-averse employees can be attributed primarily to a perverse incentive structure of the organization. Such an incentive system suppresses innovation.

One critical practice for innovation is providing incentives for enterprise. Such incentives must be asymmetric in their reward structure: strong incentives for successful innovation but weak penalties for failure. An asymmetric incentive structure encourages employees to take on risky projects. Incentives are powerful, vitally important for innovations, and relatively easy to change by top management. Incentives can be monetary, social, and moral and must be carefully designed lest they backfire. Chapter 5 discusses the costs and benefits of setting asymmetric incentives for innovation. It describes five case histories that illustrate these principles in action.

For example, Google allows employees 20% of their time to focus on innovations. Google encourages all its employees to experiment. If they succeed they are rewarded. If they fail, they are asked to learn from their errors and move on. Thus, Google has strong incentives for success with little penalty for failure. Note, 20% time is risky (because most innovations fail) and costly (because it takes time away from current priorities). So, the firm absorbs the risk of innovation, but gives the employee rewards for success, motivating the employee to innovate.

The second practice for innovation is establishing internal markets. Most firms encourage cooperation among employees. Employees themselves much prefer a friendly, cooperative environment to a competitive one. In contrast, internal markets encourage teams, divisions, and business units within a firm to compete productively with each other to develop innovations. In so doing, the firm brings within the organization the competition that it faces in the external market. When a new group or division is entrusted with an innovation, the ensuing internal competition directly fosters a willingness to cannibalize current products, an essential trait for innovation.

For example, for over a decade, HP supported inkjet and laser technologies with competing laser printing and deskjet printing divisions within the company. Each division worked hard to promote its own technology. As a result, HP grew as both rival technologies flourished. An internal market is a powerful practice for innovation. However, it has tensions and costs and could easily degenerate in to self-destructive competition. Chapter 6 discusses with examples the characteristics and types of internal markets and means for implementing and managing them.

The third practice for innovation is empowering innovation champions. Many organizations today treat their talent as employees with set tasks, times, and routines. Employees tend to dislike change, prefer stability, and make decisions by consensus. An innovation champion is an individual within the firm who is entrusted with a mandate to explore and develop innovations for current or new markets. The champion is also provided with a team and resources to actualize this mandate. Because of the champion's special mandate, he or she is not encumbered with the firm's current successes, commitments, or products. Innovation champions exemplify the traits of an innovative culture. They are comfortable with change, embrace risk, and want to shape the future. The champion can then imbue the same spirit in the team. Champions are more than mere innovators. They not only invent innovations but also develop innovations, take them to market, and steer them into successful products. The history of innovation suggests that champions are sometimes not fully appreciated in the organization. The very traits that make them productive create conflict with the larger organization. The exodus of champions is one of the greatest losses an incumbent experiences in the field of innovation.

For example, one of the champions of the iPod was Tony Fadell. Fadell's vision to create a digital music player developed while he was a VP of Strategy and Ventures at Philips, where he was in charge of Philips's digital audio strategy. He left without being able to realize his vision. He tried to develop a digital music player as an entrepreneur, but failed on his own. However, Apple recruited him and entrusted him with the development of the iPod. In this case, Philips's inability to retain and empower a champion, and Apple's ability to attract and entrust the same individual as a champion, resulted in dramatically different fortunes for the two companies.

Chapter 7 discusses with four other case histories how firms must move from managing employees or supporting innovators to empowering champions. It discusses the tradeoffs involved with this move. One of the big myths in innovation is that innovators or champions are just lucky individuals. Chapter 7 dispels this myth with examples and scientific studies. The chapter also provides steps in empowering champions within the organization.

Figure 1.1 graphically depicts the dynamics of the components of establishing a culture for unrelenting innovation. It shows that three practices promote three traits that in turn drive innovation. This leads to market success and dominance. However, market dominance has a negative feedback loop, negatively affecting the prevalence of the traits—that is, the incumbent's curse. The practices have the potential to break the incumbent's curse and foster innovation.

This explanation of culture as a cause of failure differs substantially from other explanations offered in the literature on innovation.

Culture as a Primary Explanation

Various scholars have proposed numerous alternate explanations for why great incumbents fail. Some claim that incumbents fail because they fail to invest in research and development. Some claim that incumbents fail because they succumb to pressure from Wall Street (investors) for short-term profits. Others claim that incumbents fail because they do not invest in emergent technologies. Still others claim that incumbents fail because they lack patents. Although there is an element of truth in all these explanations, our research indicates that these explanations do not get to the root cause and do not fully gel with the evidence (see Chapter 8 for details). For example, Nokia had a color touch screen Phone more than seven years before Apple introduced the iPhone.17 HP had an e-reader before the iPad. Microsoft had a search engine with paid ads before Google's search engine took off. Sony had an MP3 player before the iPod. Kodak had a digital camera before every other firm. Until recently it owned most of the patents in digital photography. Xerox had most of the innovations associated with the personal computer, well before every other firm. In all these cases, the incumbent had more resources, R&D, patents, and even prototypes of innovations than the firm that successfully commercialized the radical innovation. Yet the incumbent failed to do so.

Why then do these great incumbents fail? Simply, it's culture. Great firms fail because of the incumbent's curse—a culture that resists cannibalizing successful products, abhors risk, and focuses on the present. In so doing, the dominant firm overlooks radical innovations that often emerge deep in the bowels of the organization. In contrast, firms that succeed embrace a culture for unrelenting innovation embodied by the three traits and three practices summarized in this chapter.

Most rival explanations attribute failure of incumbents to external factors. My explanation is an internal one. Most rival explanations attribute failure to hard factors: resources, technology, patents, or country. My explanation is a soft one: culture. Most rival explanations attribute failure to a simple causal structure from one exogenous factor to innovation. Mine is a subtle one, involving a critical reverse pathway: success from innovation leads to the incumbent's curse which stifles further innovation. Culture is not only a driver of innovation. Culture is also endogenous to the system. Success corrodes culture through the phenomenon of the incumbent's curse. The enemy is within!

Firms differ in their grasp of the importance of culture. Some firms get it and have for the most part stayed at the cutting edge of innovation: for example, Facebook, Google, Gillette, 3M. Some firms stumbled but drastically changed culture to regain the lead in innovation, for example, IBM, Samsung, P&G, GM. Some firms struggled or struggle to grasp the causes of decline and the role culture plays, for example, Kodak, Sony, HP, Nokia, RIM. The thesis of this book is that culture distinguishes the first and third group of firms. A change in culture explains the change in the second group of firms.

Basis for the Book

This book is based on the collective wisdom of many research studies on innovation that my coauthors and I have conducted over the last two decades. Some of these studies have already been cited in this chapter. The data collection alone for each of these studies took two to four years. In addition, all the studies were published in top academic journals after going through double-blind peer review. The review process generally took another couple of years. There is an advantage in this self-inflicted pain: through such review, the methods are scrutinized, the reasoning carefully analyzed, and the hypotheses matched against data and models. After publication, a number of these studies won best paper awards from their respective journals and other groups.18 A synopsis of some of the major studies that provide the basis for the conclusions of this book follows. Details are in Chapter 8.

Chapter 8 covers these studies in some detail and compares them with findings from other published work. In addition, I have made hundreds of presentations worldwide and talked about innovation with numerous executives from major multinational corporations and small start-ups. I also draw on research in other fields that has important lessons for the management of innovation.

These studies and extensive discussions provide the basis for the observations and conclusions of this book.

Conclusion

Technological evolution is constant and increasing. It shapes consumers' tastes and prompts them to demand ever-higher performance on ever-changing dimensions. Such change requires that firms innovate unrelentingly. Innovation requires great resources. Dominant incumbents are in the best position to innovate and stay at the top of the game because of their deep pockets, vast experience, and great expertise.

Yet a review of the history of markets shows that many incumbents do not sustain their dominance for long. They fail primarily because they pass over the next wave of innovations that threaten to transform their markets, jeopardize their cash flows, or render their successful products obsolete. Ironically, many of these market leaders rose to their level of dominance by commercializing a radical innovation. The reason they fail is that their very success generates a culture that inhibits innovations. Such an unproductive culture involves three traits: a fear of cannibalizing current successful products, a focus on solving current problems, and an intolerance for risky, uncertain innovations. Because these self-destructive traits result from success, my coauthors and I call this phenomenon the incumbent's curse.

Fortunately, our research shows the incumbent's curse is not insurmountable. It can be broken by three traits that foster innovation: a willingness to cannibalize a firm's successful products, tolerance for risk, and focus on the future. However, such traits are deeply human characteristics that form slowly and do not respond to managerial fiat—that is, managers cannot simply enforce them. Our extensive research shows that firms can adopt three practices that foster these traits: providing incentives for enterprise, fostering internal markets, and empowering innovation champions. Figure 1.1 depicts the hypothesized model for breaking the incumbent's curse. The next six chapters discuss each of these six components of culture in depth. The chapters elaborate on the theory, explain the processes, and provide prototypical examples of each component of culture. The final chapter details evidence in support of this thesis and against other classic explanations of innovativeness. It describes precise metrics by which firms can measure each component of culture. It also describes a database of 770 global firms of varying sizes and in varying markets, against which firms can benchmark their own level of innovativeness.

The incumbent's curse involves a perennial paradox. Market dominance demands unrelenting innovation. Development of radical innovations has the potential for success and market dominance. But market dominance leads to confidence, complacency, and inertia resulting in a failure to innovate. The failure to innovate leads to loss of dominance and ultimately market failure. Thus, success carries the seeds of its own self-destruction. Innovation leads to market dominance, but market dominance corrodes the traits that foster innovation.

As a result, there are no permanently successful firms. Market dominance generates resources, experience, and expertise but no guarantee for continued success and market dominance. Long-term dominance belongs only to those firms that carefully nourish and sustain a culture for unrelenting innovation against the forces that destroy it.

1 Golder, Peter N., Julie Irwin, and Debanjan Mitra, “Do Economic Conditions Affect Long-Term Brand Leadership Persistence?” Presentation at the Conference of Theory and Practice of Marketing, Harvard Business School, May 5, 2012.

2 Golder, Peter N. and Gerard J. Tellis, “Pioneering Advantage: Marketing Logic or Marketing Legend,” Journal of Marketing Research, 30, no. 2 (1993): 158–170; Tellis, Gerard J. and Peter Golder, Will and Vision: How Latecomers Grow to Dominate Markets (New York: McGraw Hill, 2001).

3 A radical innovation is a new product, service, process, or business model that is based on a new scientific principle and provides substantially superior consumer benefits than was possible with the prior scientific principle in use. Chapter 2 describes this concept in depth.

4 Chandy, Rajesh and Gerard J. Tellis, “The Incumbent's Curse? Incumbency, Size and Radical Product Innovation,” Journal of Marketing, 64, no. 3 (July 2000): 1–17; Chandy, Rajesh and Gerard J. Tellis, “Organizing For Radical Product Innovation,” Journal of Marketing Research, 35 (November 1998): 474–487.

5 Gerstner, Lou, Who Says Elephants Can't Dance? (New York: HarperCollins, 2002), 185.

6 Apple's iPod was first and foremost a highly user-friendly product. One of the secrets to its success was that Apple achieved this great user-friendliness even though they included strong digital rights maintenance (DRM) to prevent illegal copying of songs, in order to gain access to songs from music companies.

7 “Larry Page and Eric Schmidt Hold Court at Google Zeitgeist,” TechCrunch. September 27, 2011, http://techcrunch.com/2011/09/27/page-schmidt-zeitgeist-video/

8 “Larry Page and Eric Schmidt Hold Court,” TechCrunch.

9 See summary at end of this chapter and details in Chapter 8.

10 Gerstner, Who Says Elephants Can't Dance?, 182.

11 Ibid.

12 Jaruzelski, Barry and John Loehr, “The Global Innovation 1000,” Strategy+Business, Booz & Company, 65 (Winter 2010).

13 Tellis, Gerard J., Jaideep Prabhu, and Rajesh Chandy (2009), “Innovation of Firms Across Nations: The Pre-Eminence of Internal Firm Culture,” Journal of Marketing, 73, no. 1 (January 2009): 3–23.

14 Dvorak, Phred, “Bad Luck Swamped Successes During Stringer's Sony Tenure,” Wall Street Journal (February 2, 2012): A10.

15 See Chapter 2.

16 O'Connor, Gina Colarelli and Christopher M. McDermott (2004), “The Human Side of Radical Innovation,” Journal of Engineering Technology Management, 21: 11–30.

17 Troianovski, Anton and Sven Grundberg, “Nokia's Bad Call on Smartphones,” Wall Street Journal (July 18, 2012). Retrieved July 23, 2012, from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304388004577531002591315494.html

18 The awards include the William F. O'Dell Award for best paper from the Journal of Marketing Research, the Harold H. Maynard award for best paper from the Journal of Marketing, the Frank M. Bass award for best dissertation based article in Marketing Science, the Long Term Impact Award for the article with biggest impact over ten years in Marketing Science.

19 Golder and Tellis, “Pioneering Advantage”; Tellis and Golder, Will and Vision.

20 Chandy and Tellis, “The Incumbent's Curse?”

21 Chandy, “Organizing For Radical Product Innovation.”

22 Tellis, Prabhu, and Chandy, “Innovation of Firms Across Nations.”

23 Sood, Ashish and Gerard J. Tellis, “Technological Evolution and Radical Innovations,” Journal of Marketing, 69, no. 3 (July, 2005): 152–168.

24 Sood, Ashish and Gerard J. Tellis, “Demystifying Disruptions: A New Model for Understanding and Predicting Disruptive Technologies,” Marketing Science, 30, no. 2 (March-April, 2011): 339–354.

25 Sood, Ashish and Gerard J. Tellis, “Do Innovations Really Pay Off? Total Stock Market Returns to Innovation,” Marketing Science, 28, no. 3 (May-June, 2009): 442–456.

26 Chandrasekaran, Deepa and Gerard J. Tellis, “The Global Takeoff of New Products: Culture, Wealth, or Vanishing Differences,” Marketing Science, 27, no. 5 (September-October 2008): 844–860; Tellis, Gerard J., Stefan Stremersch, and Eden Yin, “The International Takeoff of New Products: Economics, Culture and Country Innovativeness,” Marketing Science, 22, no. 2 (Spring, 2003): 161–187; Golder, Peter N. and Gerard J. Tellis, “Will It Ever Fly? Modeling the Takeoff of New Consumer Durables,” Marketing Science, 16, no. 3 (1997): 256–270.