Chapter 2

Willingness to Cannibalize Successful Products

Today's emerging giants face a paradox. Their continued success requires turning away from what made them successful.

—Tarun Khanna, Jaeyong Song, and Kyungmook Lee1

THE HISTORY OF INNOVATION is littered with firms that pioneered and dominated markets but failed to capitalize on their leadership. Often, the dominant firm failed to capture an emergent market that splintered from the old market. Chapter 1 cites the examples of Sony in digital music, Xerox in the electronic office, Microsoft in search, Kodak in digital photography, Nokia in smart phones, and HP in tablet computers. One important reason for this failure was a reluctance to cannibalize the incumbent's successful products. Ironically, in the cases mentioned, researchers in the firms' own labs had developed the new technologies that threatened their successful products.

Should a firm introduce an innovation that will cannibalize its current successful products? This is a perennial problem facing dominant incumbents. For example, consider the following dilemma, which HP faced in the mid-2000s.2 Should it market a tablet that makes it easy for consumers to create, distribute, and read papers, newspapers, and magazines electronically? What if potential sales and profits from the tablet are initially a fraction of those from its leading products? What if margins from the tablet are lower than margins from printer cartridges? What if marketing the tablet runs the risk of cannibalizing sales of its printers, cartridges, PCs, and laptops? If one makes a strict cost-benefit analysis, then the answer to these questions, especially the last one, may well be no. Indeed, some economists have built sophisticated models to come to a similar conclusion.3 This chapter will argue that being willing to cannibalize successful products is difficult but essential to commercializing radical innovations.

Why Incumbents Are Reluctant to Cannibalize Products

Our research suggests several economic and organizational factors that justify not cannibalizing the firms' own products with radical innovations.

Economic Factors

Many economic reasons weigh against cannibalizing successful products:

- Costs and margins. After taking into account the costs of capital, retooling, marketing, and smaller potential margins, returns from innovations may seem too low to allow the firm to cannibalize successful products. For example, the returns from Kodak's film business dwarfed expected profits from digital photography in its initial years. It does not seem to make sense to push an innovation that generates lower margins and costs more than current products.

- Thresholds. Some firms use thresholds to help with selection of innovations. Such thresholds can become daunting if the firm has high current sales. For example, at one time, P&G used a threshold of 10% profit margin for introducing a new product. However, many new products do not turn profitable until after sales take off, which might not happen for two to six years. At one time, HP used a threshold for a radical innovation of 3% of corporate sales within three years. With over $100 billion in annual sales, this is a steep threshold for most new products.

- Wait-and-see. Firms can adopt a wait-and-see attitude. They may believe that they need not develop an innovation until a rival does so successfully.

- Acquisition. Firms may believe that there is always the option of acquisitions—that is, they can acquire successful innovators, especially if they are small.

These economic reasons can provide a strong rationale for not introducing an innovation that cannibalizes its own successful products.

Organizational Factors

Besides these economic reasons, several psychological factors also play a critical role.

- Resistance from internal stakeholders. To embrace an emerging innovation that threatens current products requires the support and involvement of all levels of the organization: junior employees, senior managers, and rival divisions. Sometimes senior managers agree to the change but middle or new managers do not. The latter, through delay or conscious effort, may sabotage plans for the emerging innovation. The case history of Kodak's digital photography described later in this chapter illustrates this challenge. At other times, junior managers spot the innovations, develop them, and bring them to senior managers. But senior managers are not convinced. Senior managers may veto plans for change and even drive away the potential champions of the innovation. The latter go on to form new companies or join other competitors who market the radical innovations. The case history of Microsoft Keywords described later in this chapter illustrates this point. At still other times, innovations may be developed by one division, while current products are marketed by a rival decision. If the firm requires consensus building for launch, negatively affected divisions may never acquiesce into supporting a cannibalizing innovation. The case history of Sony's MP3 player described later in this chapter illustrates this point.

- Bureaucratic committees and procedures. To efficiently manage products, firms develop committees and procedures. However, success with current products can cause such committees and procedures to grow into bureaucratic obstacles to swift embrace of key innovations. For example, Nokia's delay in developing touch-screen smartphones was partly due to such internal bureaucracy. One analyst describes the environment like this, “A ‘brand board’ discussed branding. A ‘capability board’ looked at information technology investments. A ‘sustainability and environment board’ monitored Nokia's green credentials.”4 As a result, an employee complained that Chinese manufacturers were “cranking out a device much faster than …the time that it takes us to polish a PowerPoint presentation.”5

- Perceived invulnerability. Firms with successful current products develop an aura of success, invincibility, and even arrogance. Such firms are suspicious of or belittle innovations, especially if they come from small entrants or appear inferior to current products, as innovations often do. Such firms may think they are almost invulnerable. For example, just prior to 2007, Research in Motion (RIM) was famous for its BlackBerry, which dominated the market for smartphones. The key features of the phone were secure email and hard QWERTY keyboard that appealed to business users who need to keep in constant touch with colleagues and customers. When Apple's iPhone first came out, the company's managers just could not believe it would present any challenge to the BlackBerry. Dartmouth Professor Ron Adner explains the attitude of senior managers thus, “They looked at the iPhone and dismissed it.” By the time RIM introduced their touch keyboard, the iPhone was in its fourth generation and had grown to be a huge success. By 2012, RIM lost $60 billion, or 90% of its market value.

- Biases. In addition to these factors, biases can exaggerate the importance of the present moment and undermine the importance of the future. Chapter 4 discusses in depth how and why overweighting the present and underweighting the future sabotages the development and commercialization of innovations.

Thus, economic reasons provide a good rationale for not introducing innovations that might cannibalize a firm's own products. However, organizational factors lull firms into a false security or hamper change for innovations. The organization's reasons are particularly pernicious as some are difficult to spot and all are hard to change. The combination of organizational and economic reasons can cause a dominant firm to believe its position is safe, its stream of profits secure, and its promising innovations unnecessary. There is certainly no urgency to do the apparently irrational—to cannibalize its own successful products.

Why Willingness to Cannibalize Is Important

The organizational mind-set described above probably explains why so many firms that dominate markets fail to maintain that dominance when new technologies strike. These failures underscore the need for firms to be willing to cannibalize their successful products. Some strong reasons suggest why this policy should be a priority within the firm.

Finite Growth of Current Products

Success with current products is finite, because the growth that sustains them ultimately comes to an end; that is, growth is euphoric when it happens, but it cannot last forever. All growth markets eventually see maturity and, frequently, decline. Maturity sets in either because a new product has reached all potential consumers or because a better product enters the market.

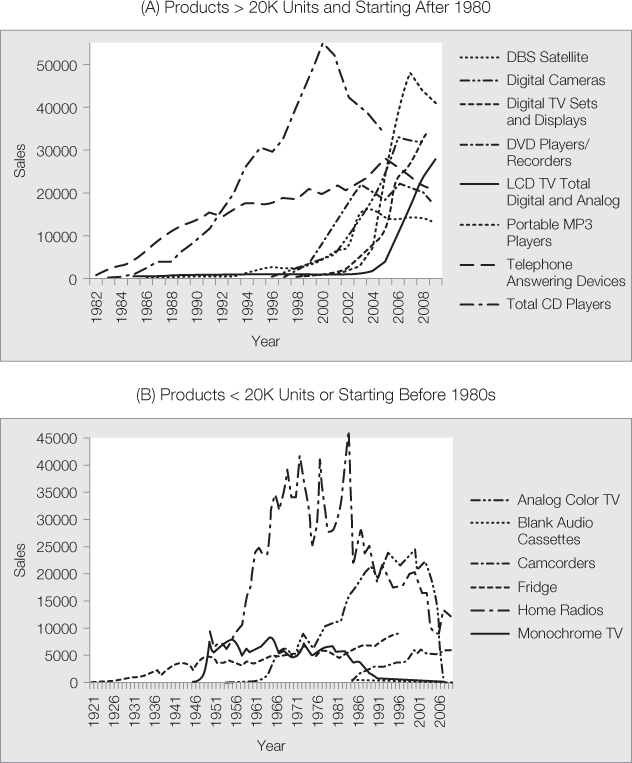

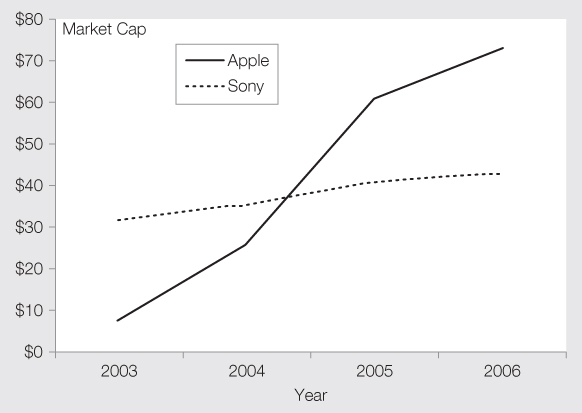

Professor Deepa Chandrasekaran and I studied the introduction, growth, and decline of sales of over twenty radically new products across thirty countries (over four hundred life cycles in all).6 One of our findings is in Figure 2.1, which shows the start, rise, and maturity of sales of some radically new products in a number of categories in the United States. The curves all show a slow start, rapid growth, and ultimate maturity. For older innovations, those introduced before 1980, the curves also show a sharp decline after maturity. Similar patterns exist for most countries. Firms need to be prepared with the next round of innovations well before the current products reach maturity.

Figure 2.1 Life Cycle of Radically New Products in the United States

Source: Based on data collected by Prof. Deepa Chandrasakran.

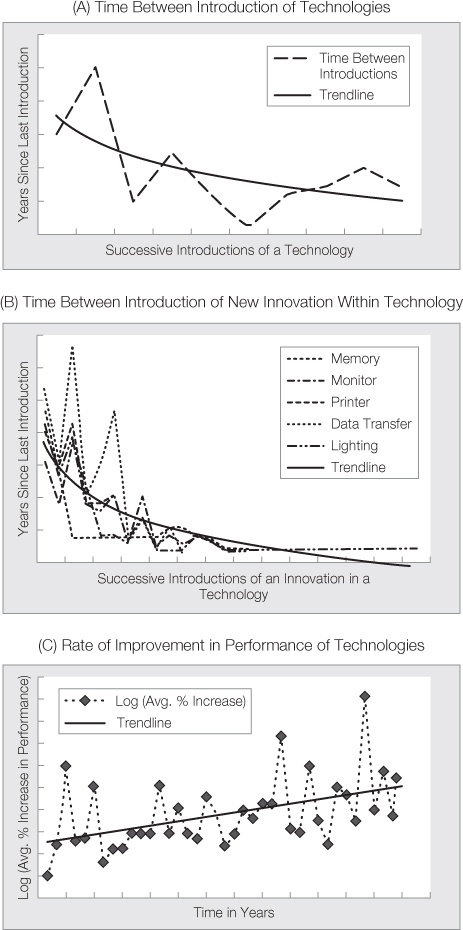

Increasing Rate of Innovation

The speed of technological change is increasing over calendar time (see Figure 2.2, which depicts the rate of technological evolution).7 We can see this pattern based on multiple dimensions. Figure 2.2A shows that the average time between introductions of entirely new technologies is steadily decreasing over time. Figure 2.2B shows that the average time between innovations within the same technology is also decreasing over time. Figure 2.2C shows the average annual rate of improvement in performance of any technology is increasing exponentially over time. Thus technological change is not only occurring, but doing so at an increasingly rapid rate. So, firms have to be constantly vigilant.

Figure 2.2 Rate of Technological Evolution

Source: Adapted from Sood, Ashish and Gerard J. Tellis, “Technological Evolution and Radical Innovations,” Journal of Marketing, 69, no. 3 (July 2005): 152–168.

For example, Samsung Electronics has grown to be one of the biggest technology firms in sales by regularly embracing new markets and new technologies. Its growth has been at least partly driven by the strong belief of its chairman, Lee Kun-Hee, that the firm has to constantly invent new businesses to survive and flourish. Under his stewardship, “Samsung thrives on a culture of impending doom”—a belief that “Samsung could disappear in an instant if it misjudges the next big trend.”8

Limitations of Acquisitions

One can easily refute two of the defenses against cannibalization posited earlier: wait-and-see and acquisition. Wait-and-see implies that a firm should wait to see how an innovation fares and only market its own version when a rival's innovation appears to take off. In most cases, this strategy is not as simple as it appears because entering a new market with an innovation requires years of development that cannot be done overnight. Thus, wait-and-see generally means waiting till a rival's innovation has taken off in the market place and won acceptance if not become a standard. But at that point, it is late for a firm to start development of a rival product from scratch. Microsoft has still not found a competitor to Google's search despite striving to do so. Sony has still not found a rival to Apple's iPod though it's over a decade since the iPod's introduction. Google has still not found a rival to Facebook's social network despite many big attempts to do so.

What about acquiring the target with the hot new innovation? Acquisition is another common defense against cannibalizing current products; that is, a firm can acquire a target if and when its innovation is threatening a firm's own successful product. There are several risks with acquisition:

Though acquisitions are common, and a few pay off handsomely, the risks are huge and the average net present value of acquisitions may well be negative. Our research shows quite clearly that making innovations internally leads to a consistently positive spike in the stock price of the innovating firm.9 Acquiring firms for their innovations leads to a consistently negative spike in the stock price of the acquiring firm.10 Thus, the market rewards internal organic innovation and punishes external acquisitions.

Challenge of Technological Change

Technology constantly changes due to basic research in academia, applied research in corporate labs, and numerous innovations by various companies. Success on one technological platform, however strong, does not guarantee permanent success. The history of technology evolution shows that new technologies constantly arise, providing new and better ways to solve old consumer needs. Understanding technological evolution may be critical to planning for the future and being willing to cannibalize existing products. The next section covers this issue in depth.

Understanding Technological Evolution

Threats to current products may come from a change in consumer tastes. However, in many if not most markets, threats to current products come primarily from technological evolution. Even for fashion goods that depend on passing consumer tastes, changes in technology frequently determine what new materials are available and what new fashions are possible. Thus, a deep understanding of the opportunity and threat of cannibalization depends on understanding the dynamics of technological evolution.

For this purpose, Professor Ashish Sood of Emory University and I conducted a study of the evolution of all technologies introduced in seven markets over broad time periods. Our findings show that technological evolution is rich, complex, but tractable. In particular, the analysis provides novel insights, which can be encapsulated into four managerial decisions: on which level to innovate, what are the patterns of evolution, on which dimension to focus, and which technology to choose.11

On Which Level to Innovate?

The received wisdom does not distinguish levels of technological change. In contrast, our deep study of technological evolution suggests three levels on which firms can innovate: platform, design, or component (see Table 2.1). A platform is the most basic level and relies on a unique scientific principle distinctly different from other principles. For example, in displays, four different technologies rely on four distinct scientific principles for forming an image on a screen: CRT, LCD, Plasma, and OLED. In this book, I use the terms platform innovation or radical innovation synonymously. On any platform, a variety of designs, which are layouts or linkages of parts, can achieve the same function. For example, a regular fluorescent bulb and a compact fluorescent bulb use different design, though both are based on the principle of fluorescence. A design innovation is a new layout or linkage of parts that is different from the prior one in use. On any platform or design, firms can use a variety of components, which are materials or parts to achieve some function. For example, a fuel cell could use hydrogen or methanol to generate electricity. A component innovation is a material or part that is different from the prior one in use.

Table 2.1 Defining Levels of Technology Innovation

| Level | Definition | Example in Displays |

| Platform | Unique scientific principle | CRT, LCD, Plasma, OLED |

| Design | Linkage or layout | 5″, 25,″ 45″ size in LCDs |

| Component | Material or content | Glass, plastic in LCDs |

Source: Adapted from Tellis, Gerard J. and Ashish Sood, “A New Framework to Help Firms Select Among Competing Technologies,” Visions, PDMA, Vol. XXXIV, No. 3, 18–23, Oct 2010.

Within any platform, innovation occurs almost constantly in design and components.12 Routine innovation occurs at these two levels. Platform innovations are not frequent, but when they do occur, they have the potential to disrupt markets and firms. The danger to firms is to be so focused on in design and component innovation as to miss platform innovations. For example, Sony's preoccupation with improving its CRT television sets with Trinitron technology led it to miss the oncoming revolution in flat-screen LCD TVs. Samsung innovated greatly in the latter technology so that Sony had to license technology from Samsung.

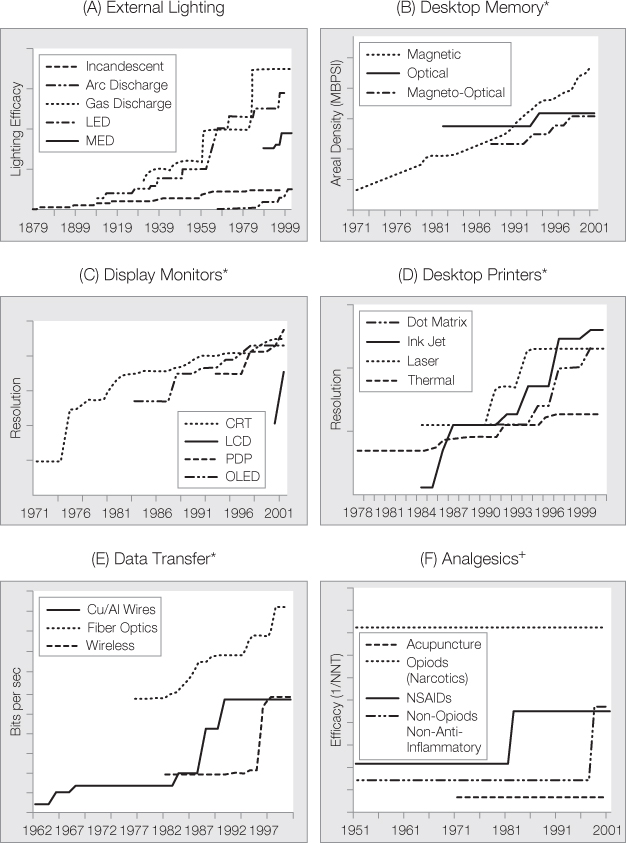

What Is the Pattern of Evolution?

The received wisdom is that a new technology always enters below an older technology and always follows a single S-shaped curve. In contrast, our analysis of these seven markets shows that technological evolution is rich, complex, but tractable (see Figure 2.3). In particular, we can identify several novel patterns of technological evolution.

Figure 2.3 Technological Evolution in Six Markets

* Performance on Y axis in Log Scale.

+ Accurate performance records of efficacy of acupuncture not available prior to 1971.

Source: Adapted from Tellis, Gerard J. and Ashish Sood, “A New Framework for Choosing the Right Technology,” PDMA Visions (October 2010):18–23.

Take the case of technological competition in the desk top printer market in Figure 2.3D. In 1991 Laser technology surpassed ink jet technology in performance. That was not a sufficient reason to abandon the ink jet technology. Indeed in 1997, inject technology passed laser technology in performance. HP marketed printers with both technologies. It supported both these rival technologies simultaneously. This turned out to be a wise strategy because HP has dominated the printer market with superior products using both these technologies. The lesson for firms is that they need to support or at least monitor a portfolio of technologies so that firms are prepared for the sudden surge in performance of any single one technology.

On Which Dimension of Performance to Focus?

The current thinking in marketing and technology circles is that customer tastes determine which dimension of performance is important. Firms change their products to meet this changing demand. In other words, changes in tastes drive changes in technologies and products. In contrast, we find the reverse to be the case. That is, changes in technologies drive changes in tastes. In particular, in each market, each time a new technology enters the market it brings into play a one or more new dimensions of performance. Consumers then get excited about the new dimension and begin to choose products based on their performance on that dimension. As a result, markets show a sequence of shifting focus on dimensions. Table 2.2 illustrates this point.

Table 2.2 Emergence of Dimensions by Market Across Time

| Market | Emergence of Successive Dimensions Over Time |

| External Lighting | brightness → color rendition → life → compactness |

| Desktop Memory | density → reliability → portability |

| Display Monitor | resolution → compactness → screen size → convenience |

| Desktop Printers | resolution → graphics → speed → color rendition |

| Data Transfer | speed → bandwidth → connectivity |

| Analgesics | analgesia → reaction speed → targeted-action → reduced side effects |

Consider the market for display monitors. When CRTs were the only technology, the dimension of interest was resolution. When LCDs entered the market, the dimension of performance shifted to compactness (thinness and lightness). When plasma entered the market, it brought the dimension of screen size into play. Now, as OLED becomes popular, it will bring into play the dimension of convenience. Thus, new technologies make possible new dimensions of performance that excite consumer interest. Technological change seems to drive or shape consumer tastes!

Technological change also makes possible new products for new or transformed markets. For example the development of LCD monitors made possible the market for laptops. The development of plasma transformed the market for large screen public displays. The development of LED made possible the market for compact high-definition TVs for home. Very thin OLED screen will revolutionize the markets for mobile displays and large screen TVs for the home.

So far, this chapter has discussed why cannibalization is difficult, why it is important, and how we can understand technological evolution. We now turn to five case histories. A close look at these cases illustrates how these various factors played out in real market situations and reemphasizes the importance of the principles discussed.

Blinded to an Opportunity: Microsoft Keywords?

From humble beginnings in the 1970s, Microsoft grew to become a giant company because of its innovative products (DOS, Windows, Office) in PC operating systems. However, in the 2000s, Google outshone Microsoft with explosive growth due to its innovation in search. Google grew from its origins in 1998 to a market capitalization of $234 billion at its peak in fall 2007. In this growth, Google surpassed and dwarfed Yahoo!, which had a search engine before Google. Google grew so fast that software giant Microsoft tried to catch up by developing a search engine of its own. When that effort was not successful, Microsoft tried to acquire Yahoo! in 2008, in order to build Yahoo!'s search engine. But Microsoft need not have gone so far. The company had a search service called Keywords, which it stymied and killed for fear it would cannibalize its older advertising business. The chain of events that led to the demise of Microsoft Keywords is instructive.13

At the start of the World Wide Web around 1995, a university of Illinois student, Scott Banister, thought of the idea of adding paid ads next to search results. To develop his idea, he quit college and moved to California in 1996. Two years later, he joined a company called LinkExchange, a popular Internet advertising cooperative. In November of that year, Microsoft bought LinkExchange for $265 million.

Microsoft's goal in the acquisition was to help it distribute its online ads to websites. However, Ali Partovi, who then ran LinkExchange, tried to sell Microsoft on the idea of Keywords, originally developed by Banister. He made monthly trips in 1999 for this purpose, trying to persuade his bosses to auction off keywords that could be placed next to regular results of search (similar to what Google currently does). “This is the next big thing,” Partovi is supposed to have told Bill Bliss, the leader of the online group's Web-search team.14 Bliss was sympathetic to the idea.

However, at the time, the threatening spot on Microsoft's radar was the rapid growth of AOL. Microsoft's top leaders thought that Internet revenues would come through user subscriptions for such sites as AOL or MSN, or from banner ads on these sites. The leaders did not see the future in paid search. Bliss was also skeptical of mixing search results with paid ads because he feared the ads would compromise the quality of the offering.

In 2000, a new leader of the online group finally got permission for Partovi to run a live test program of Keywords on Microsoft MSN. Advertisers began to place sponsored links on the service and advertising revenues flowed in. However, some managers feared that this service would cannibalize the main advertising revenues on MSN, which at that time came from banner ads. So they placed a restriction on Keywords. The minimum bid was set at $15. (Though this might appear low, Google currently has a five-cent minimum on bids.) Partovi believed that the $15 limit was too high and would drive away many advertisers. On paid search, revenues came from a large volume of low bids for keywords. Partovi even ran an unauthorized test without this price restriction. That test outraged bosses at MSN. The leader of the online group asked Partovi to end the test and stay away from company headquarters for a while.

Then in May 2000, after Keywords brought in about $1 million in revenues, Microsoft shut it down. “In retrospect, it was a terrible decision,” said the manager of the online group who had obtained Partovi's permission for the live trial of Keywords. “None of us saw the paid search model in all its glory.”15 The lack of vision was in not realizing that revenues came from a large volume of low bids. Ironically, Microsoft's overt reason for the shutdown was that the revenues were lower than the company's other revenue streams. Yet, the minimum bid restriction on Keywords prevented it from realizing its true potential in revenues! Ultimately, fear of cannibalizing other advertising revenue streams had killed the great potential of Keywords.

In October 2000, Google launched its own version of combining search with auctioned keywords, called AdWords. It went on to become the most successful model for revenues on the Web, propelling Google to grow into one of the highest valued corporations on the stock market. Google is so large today that it poses a threat to Microsoft. In particular, Google is considering office software and web browsers that would threaten some of Microsoft's core revenue sources. In the meantime, Microsoft continues to struggle to develop a paid search service that matches Google's.

Crippled by Fear of Piracy: Sony MP3 Player

In the summer of 2001, Kunitake Ando, then president of Sony, had a vision that was pretty good for its time. He predicted that “the personal computer was quickly losing its status as the heart of the information revolution. The real action in information technology would migrate to the living room, the family room, the automobile, the beach, the holiday retreat …net-capable audio and video gadgets, cell phones, and games would keep [people] entertained and in touch.”16 The average consumer might have half a dozen gadgets, each with a hard disc and be able to zap information to each other and to and from the Web, making life rich, fast, and exciting. Ando wanted Sony to reinvent itself for this age.

However, by early 2003, the executives at Sony headquarters were facing a problem which was “small enough to fit in their pockets” yet “heavy enough to weigh on their minds.”17 The problem in question was Apple's iPod, the cool little MP3 player that had captured the consumer's imagination in the same way Sony's Walkman did some twenty years earlier. Ideally, Sony should have owned the portable music player business because of its creation and domination of that market with the introduction of the Walkman. But the new century's new Walkman belonged to Apple, not Sony.

Ando's vision did not become reality because Sony was hampered by a fear of piracy. An example of this fear was Sony's digital Walkman. Whereas the iPod lets a user synchronize its contents with the user's music on a laptop or personal computer, Walkman users were hampered by “laborious check-in/check-out” procedures designed to prevent illegal file-sharing.18 When asked about a Walkman with a hard drive, Keiji Kimura, then senior VP at Sony headquarters, said, “We do not have any plans for such a product, but we are studying it.”19 In fact a Sony Walkman with a hard drive was highly unlikely because Sony's copy-protection didn't allow music transfers between hard drives.

Sony was facing a peculiar predicament with its electronic and entertainment divisions facing opposing priorities. Its electronics business understood consumers' needs and wanted to help them move files around freely. However, its entertainment business was concerned about illegal copying and wanted to build barriers to move files freely. “We have many things to resolve,” Kimura acknowledged. “Protection is one side of it—of course we have to protect our copyrights. But the challenge is how to excite the user.”20 Electronics companies were aligned with Napster to produce electronic gadgets that enabled free copying of music and videos. However, entertainment companies were aligned with the movie and recording companies to prevent illegal copying. In a way, the priorities of the music and movie businesses (protecting piracy) ran in direct opposition to those of the MP3 player business (ease of use including easy copying!). Sony had let the battle in the marketplace get within the corporation and paralyze its innovative efforts.

At its core, the fear of piracy was a fear of cannibalization. Sony's acquisitions in the last decade had deepened this conflict. In August 2004 Sony set up a joint venture with BMG (Bertelsmann Music Group), the world's third largest music publisher. In April 2005, Sony bought MGM (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc.), a well-known motion picture studio in Hollywood. Both these units were in the business of developing and protecting music and movie labels from which they earned royalties. Illegal copying by consumers was a big threat to these businesses. But to prevent illegal copying, Sony also created obstacles to legal copying by a user for himself or herself. Thus, fear of cannibalizing music and movie revenues crippled Sony's efforts to develop a user-friendly MP3 player.

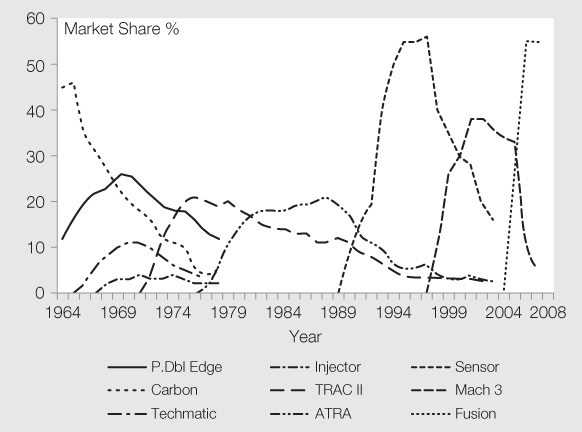

Apple exploited this weakness of Sony with the successful launch of the iPod and the expansion of its family of products. Further, Apple also introduced and has run the successful iTunes Store for downloading songs, even though Sony could have beaten Apple to it, given its ownership of Sony Music, which has the second largest collection of recorded music. Before the iPod, Apple was a fifth of the size of Sony. Five years after the launch of the iPod, Apple grew to be twice the size of Sony in market cap (see Figure 2.4). The iPod platform prompted Apple to launch the iPhone and then the iPad, other successful products with huge sales and profits.

Figure 2.4 Annual Market Capitalization of Sony and Apple After Launch of iPod

Sony has made determined efforts at reinventing itself to overcome these problems. One of the radical changes it made was to hire British-born Howard Stringer as CEO of the company in June 2005. But even he struggled with Sony's culture. “The whole security/digital rights management/copyright arena is a critical battlefield,” said Howard Stringer. “We all have to invent the business plan for the future. And even though we have sides of Sony that will disagree, finding a consensus is Sony's style.”21

The deep-seated culture at Sony is a big hindrance to change. Central to this culture is decision by consensus. Such consensus needs to be arrived at within and between divisions. In general, consensus building is a good trait. But when it gets in the way of timely decisions to embrace innovations for the future, it is bad. Sony was unable to move ahead swiftly and effectively because a commitment to consensus prevented it from resolving the conflict between divisions. Rivals such as Apple are able to move nimbly with new models catering to the needs of the market because they are unencumbered with the size and culture that belong to Sony. Commenting on the swift and decisive decisions taken by Steve Jobs in the development of the iPod, Tony Fadell recalled, “I was used to being at Philips, where decisions like this would take meeting after meeting, with a lot of PowerPoint presentations and going back for more study.”22

Subsequent chapters will explore practices that can help a company overcome this fear of cannibalization and slow decision making. These practices include empowering innovation champions, incentives for enterprise, and internal competition.

Decline of an Innovator: Eastman Kodak

George Eastman founded the Eastman Kodak company in 1880 based on a relatively simple technology. He designed a box camera and roll film to replace the existing cumbersome glass plate technology for taking pictures. Initially, professional photographers resisted his innovation because of the inferior quality of Kodak's pictures. But lay people picked it up quickly because of its convenience and the product became very successful. Successive innovations over the decades led the company to dominate the photography business, primarily through its superior position in film and prints. The durable camera was the excuse for the consumable film and prints, which provided the majority of Kodak's profits. Kodak built up a commanding position in film that reached 90% in the 1970s before the growth of Fuji.

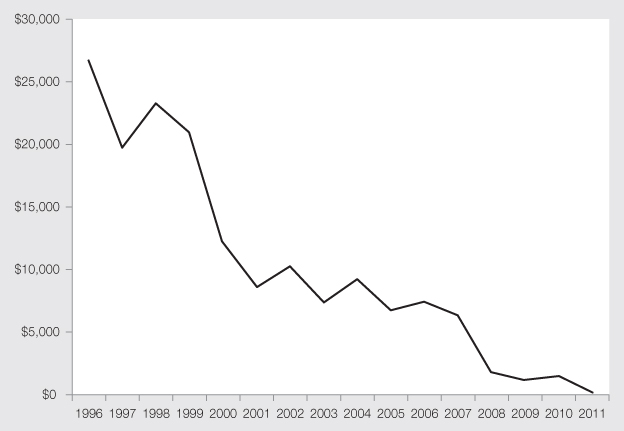

However, Kodak's great success led to a bloated bureaucracy, generous employee entitlements, and huge overheads. Success created a culture of stagnation. One reporter describes Kodak's culture as follows, “At Kodak this arrogance fueled the growth of a nightmarish bureaucracy so entrenched it could have passed for a government agency.… There was an emphasis on doing everything according to company rulebooks. …Meetings were held prior to meetings to discuss issues and establish agreement in order to avoid confrontations, which were considered un-Kodaklike.”23 Even with competition from Fuji, some cost cutting enabled Kodak to do well. Its stock peaked on Feb 19, 1997 at $94.75, when the company's market capitalization hit $30.9 billion. Subsequently, the company lost value steadily till its market cap fell below $0.2 billion in December 2011 (see Figure 2.5) and the firm later went into bankruptcy.

Figure 2.5 Annual Market Cap of Eastman Kodak 1996–2011 (US$ Millions)

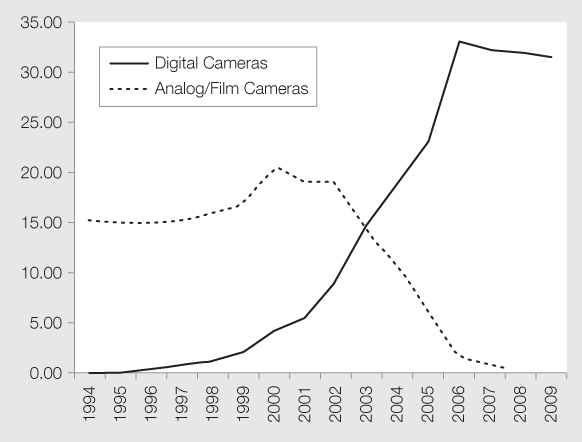

What caused this huge 87% loss in value? It was Kodak's failure to embrace digital photography even after it took off (see Figure 2.6). Ironically, digital photography was not unknown to Kodak. Steven Sasson invented the digital camera at Kodak as early as 1975.24 Subsequently Kodak produced more than fifty digital products, including the first megapixel sensor of 1.4 million pixels.25 Sasson has this to say of Kodak's contribution to digital photography: “No matter who makes which digital camera you use today, the camera uses a lot of IP (intellectual property) that Kodak first created. Kodak invented the first megapixel sensor. The first color filter tray was from Kodak. Image compression up to the JPEG standard and, of course, the first digital camera was also developed at the Kodak Labs. One of our cameras was used in the space shuttle mission in the United States in 1991. We also set up the first photo kiosk in 1994.”26 Kodak has over one thousand patents in digital photography.27 Thus, Kodak was a leader in digital technology. The firm also invested heavily on research in digital technology.28 So why did the firm lose so much value in the 2000s?

Figure 2.6 Annual Sales of Digital and Analog Cameras (Million Units)

Sources: Prepared by author based on data from GMID, Lucas, and Goh, “Disruptive Technology,” and http://www.dpreview.com/news/0401/04012601pmaresearch2003sales.asp.

The problem had to do with reluctance to cannibalize the film business. Kodak was used to selling cameras and film but made its profit primarily on film. Film was its cash cow. Digital cameras had the potential to cannibalize that business. The company was reluctant to cannibalize the film business. It hoped digital cameras would not grow to become a very big business. So, in the 1990s, it did not market digital cameras aggressively. In the 2000s, when digital cameras took off (see Figure 2.6), Kodak kept expecting profits from consumables, such as ordering of prints and the distribution and sharing of images via the Internet. Profits from these operations never came anywhere close to those from the film business, causing the decline in sales and market cap (Figure 2.5).

As a result, the company initially was not willing to do the drastic reorganization that would transform the stodgy company, more than one hundred years old, into a small nimble one that can deal with the scorching pace of the digital market. Kodak employee John White describes the clash of current and needed cultures this way: “Kodak wanted to get into the digital business, but they wanted to do it in their own way, from Rochester and largely with their own people. That meant it wasn't going to work. The difference between their traditional business and digital is so great. The tempo is different. The kinds of skills you need are different. Kay and Colby would tell you they wanted change, but they didn't want to force the pain on the organization.”29

Moreover, when some senior managers realized the need for digital technology and allocated resources for digital products, middle managers kept resisting the change. An article in Business Week described the cultural resistance thus: “The old-line manufacturing culture continues to impede [CEO George] Fisher's efforts to turn Kodak into a high-tech growth company. ‘Fisher has been able to change the culture at the very top,’ says one industry executive, ‘but he hasn't been able to change the huge mass of middle managers, and they just don't understand this [digital] world.’”30

In this case, the over one-hundred-year success with the old film technology turned into rigidities that prevented the company from embracing the new digital technology. Even when the company reorganized, creating a separate division to handle digital products, infighting between divisions prevented the new division from making a great success with digital technology. In the words of Donald W. Strickland, a former vice president, “The fear of cannibalization always slowed things down.”31 In effect, Kodak never empowered the new division with sufficient independence to compete with and if necessary, cannibalize, and kill off the film division. Unfortunately, the external digital market did that anyway. And a great innovator shrank to a fraction of its value (see Figure 2.5).

A Cycle of Cannibalization: Gillette's Innovations in Wet Shaving

Professor Peter Golder and I analyzed the history of Gillette in the wet shaving market.32 Our prior analysis and my updated analysis of its recent history suggests that Gillette's story contrasts dramatically with Kodak's in digital photography. Gillette dominated the wet shaving market for over a hundred years. For much of this time, it has had a large, relatively stable market share of 60% to 70%. What is the reason for this great dominance of the market? Figure 2.7 may provide a clue. This figure graphs market share of Gillette's brand on the y axis against calendar year on the x axis. A close analysis of this exhibit reveals an important dynamic. Even though the total share of all Gillette's brands may sum to about a stable 70%, in reality market shares of the individual brands are in constant flux. New brands enter the market at regular intervals while old brands fade away. Indeed, each brand seems to grow rapidly, reach a peak, and then decline. The rate of this rise and fall seems to occur at an increasing pace, providing further support, in addition to Figure 2.2, of the increasing rate of technological change in this market too.

Figure 2.7 Gillette's Brand Cannibalization in the Wet Shaving Market

On viewing this exhibit, the casual observer might think that Gillette has acted with great foresight. Just when an older brand is about to decline, it introduces a new brand to take its place. However, the real story may be a little surprising. Gillette introduces a new brand even when the old brand is at its peak. The new introduction cannibalizes the market share of the old brand. Gillette does so, even though in most cases no rival introduces a brand to challenge the position of its dominant brand. For example, in 1972, Gillette introduced TRAC II. This was the first razor with twin blades. Gillette introduced this innovation even at the risk of cannibalizing sales of its older successful brands. TRAC II had five years of rapid growth. In 1976, under the threat of Bic disposable razors, Gillette introduced Good News. Good News had twin disposable blades but was lower priced and cut into short-term profits of the established brands. Then, in 1977, while TRAC II's sales were still rising, Gillette introduced ATRA, with full knowledge that so doing would arrest and cannibalize TRAC II's sales. In 1989, Gillette introduced Sensor, with two independently moving blades. This innovation provided such a big improvement in performance that it commanded a premium price and reversed the losses from the lower priced disposables. While Sensor was still growing, Gillette introduced Sensor Excel that replaced the former brand. Even though Sensor Excel was growing, in 1998 Gillette introduced MACH 3, a razor with 3 pivoting blades. In 2005, Gillette introduced Fusion, a six-blade wonder that did to MACH 3 what it had done to its predecessors.

In hindsight, most of these innovations were big successes. At the time though, each innovation was risky. First, it ran the risk of cannibalizing Gillette's older brands without guaranteeing a higher profit margin. Second, it ran the risk of wasting huge expenditures in research and development and marketing. For example, Gillette spent $700 million in research and development for the MACH 3, and started those investments as much as seven years before launch. In addition, Gillette may have spent $300 million on marketing. Such risks create the fear of cannibalization that afflicts many incumbents. That is not what happened at Gillette, at least for most of its history.

Gillette introduced most innovations in shaving except for the electric razor, the stainless steel blade, and, recently, the home laser kit. It was a fear of cannibalizing its successful products that dissuaded Gillette from introducing the stainless steel blade, even though it owned some of the patents for that technology. When Wilkinson Sword introduced the stainless steel blade in the 1960s, Gillette suffered a steep drop in market share within a year. That experience taught Gillette the importance of cannibalizing successful products before rivals did so. Subsequently, by innovating ahead of competitors, Gillette maintained its dominance of the wet shaving market, even expanded overall market share, and increased profits in some cases.

The culture within Gillette provides some insight as to how it succeeded at innovation.33 Employees had a passion for the product and an obsession for innovation. At any time, Gillette had over a dozen shaving products under research. The company used its own employees to personally test its prototypes of new products. Using two-way mirrors, the company observed more than one million shaves in a recent year at its research centers.34 Employees analyzed the consumers' style of shaving, strokes used in shaving, smoothness of shaved skin, and output in shaved hair. A manager commented about his commitment to testing, “We bleed so you'll get a good shave at home. This is my 27th year. I came here my first week. Haven't missed a day of shaving.”35 A vice president of the technology laboratory described Gillette's research passion and culture like this: “We test the blade edge, the blade guard, the angle of the blades, the balance of the razor, the length, the heft, the width. What happens to the chemistry of the skin? What happens to the hair when you pull it? What happens to the follicle? We own the face. We know more about shaving than anybody. I don't think obsession is too strong a word.”36

This passion for innovation and willingness to cannibalize successful products is responsible for Gillette's unrelenting leadership of and high profits in the wet shaving market. These traits themselves sprang from past mistakes and resulting realization of the fragility of market dominance. While it led in most innovations in wet shaving, Gillette twice failed to innovate and immediately lost market share: it failed to introduce stainless steel blades and electric shavers. From these mistakes, Gillette learned that success leads to complacency that embeds the seeds of future failure. For continued success, it had to strive to develop innovative products and obsolete existing successful products.

However, even with Gillette, innovation was finite. The firm was not the pioneer of laser technology and was not quick in responding to the threat of laser hair removal devices. A small start-up introduced the first home laser hair removal set. Time will tell whether Gillette's failure in this respect will be fatal. (Gillette sold out to P&G, which acquired the entire company in 2005.) The advance of laser technology may have presented a sufficient threat to the company that it sought the support and investment of a giant consumer products company.

Late Move: HP Tablet

Similar to the previous examples, HP Laboratories had a prototype of an e-book reader in the mid-2000s.37 However, at that time the market for such products seemed small, probably less than $100 million a year. The category may have seemed like a rival to laptops, for which HP had become the major manufacturer after the acquisition of Compaq. Moreover, for a firm like HP with over a hundred billion dollars in sales, mainly from PCs and laptops, pursuing the then relatively minuscule market for e-book readers probably seemed like a distraction. Yet, the e-book reader market got credibility when Amazon introduced its Kindle in 2007. The market took off in the form of tablets when Apple introduced its iPad in 2010 and immediately threatened the PC and laptop markets.

It was only then that HP took this category seriously. HP launched the Slate in October 2010 and the TouchPad in July 2011.38 But by not aggressively commercializing such a product earlier even at the risk of threatening its own PC and laptop markets, HP may have lost a half decade of valuable product development and in-market experience. As of summer 2012, Apple remained way ahead of all competitors in its share of the tablet market.39 In September 2011, HP called it quits. It said it would abandon its TouchPad and its mobile phone because of low sales. However, it went further and said it would sell its entire personal computer and laptop business, even though it was the leading manufacturer at the time. Ostensibly, its then CEO, Leo Apotheker, said he was doing that because of small and declining margins in those businesses.40 However, the real reason would have been the growth of the mobile and tablet businesses at the cost of personal computers and laptops.

HP's failure to aggressively embrace, commercialize, and lead in the tablet market had taken the shine off the personal computer and laptop markets. Without a strong position in tablets, the future of personal computers and laptops seemed dim.

Conclusion

This chapter makes the following important points.

- Many incumbents fail to commercialize radical innovations due to a fear of cannibalizing successful products. Success is a curse. When successful products are still profitable, it is difficult to envisage the threat from an unprofitable, seemingly small, new innovation. In particular, economic and organizational factors come in the way of cannibalization.

- Economic considerations seem to weight current successful products over radical innovations. The huge investments, high failure rate, uncertain returns, and distant payoffs for radical innovations all count against them and in favor of current successful products. In addition, specific sales and profit thresholds often screen out radical innovations when compared against the scale and profits of existing firms.

- Organization hurdles include committee and procedures for approval, perceived invulnerability, and resistance from internal stakeholders. In the case of Microsoft, a few enterprising junior managers championed the search. But senior managers failed to see the light. In the case of Sony, divisional conflict and a concern for consensus failed to make a success of the design and marketing of the MP3 player that the firm had developed and commercialized. In the case of HP, the businesses were too focused on the huge PC and laptop market to pay much attention to the e-book reader that the labs had produced. The most surprising case is Kodak. The company was already the world leader in the new digital technology. Senior management, brought in to help with the transition, was in favor of the new technology but was not willing to undertake the deep organizational changes necessary to market it successfully.

- Ironically, firms overlook innovations even when they emerged in the bowels of the firm's organization. Case histories of Microsoft Keywords, Kodak digital technology, the Sony MP3 player, and the HP e-book illustrate this point. Note that in all these four cases, the new technology was developed and, in one case (Kodak), pioneered by researchers in the incumbent firm's own labs.

- Given a monopoly, focusing on current successful products may be preferable to costly innovations that may cannibalize them. But real markets are fairly competitive. If the incumbents will not innovate, competitors will. The preceding case histories show how the incumbents suffered, in some cases fatally, by not pursuing innovations.

- The driving rationale for cannibalization is technological evolution. Such evolution has certain distinct characteristics: (a) in any market, new technological platforms constantly emerge; (b) each such technology introduces one or more new dimensions of performance; (c) as a result, at any point in time multiple technologies compete on multiple dimensions to serve certain consumer functions; (d) improvements in performance of these technologies causes their performance paths to cross multiple times; and (e) the rate of technological change is increasing exponentially over time.

- Technological innovations open whole new markets and obsolete established ones. Thus, monitoring technological evolution with an eye on future growth markets may help counteract the lure of current successful products.

- Some economists have shown that the seemingly counterintuitive principle of cannibalizing one's successful products may be the optimal strategy in a competitive market.41 It is basically a principle of protecting one's market by preemptive cannibalization. Hence the logic in the saying, “Eat your own lunch before someone else does.”42

- To be unrelentingly innovative, firms must be willing to cannibalize their successful products, not only when the product is in decline, but even when it is at its peak. Gillette illustrates this strategy in the wet shaving markets. The goals, culture, and organization were all geared for such cannibalization. However, even in the case of Gillette, when a new platform in the form of laser technology emerged, the firm was not the first to commercialize it.

How can a firm instill this willingness to cannibalize as a routine attitude within the corporation? The next two chapters describe two traits—focusing on the future and embracing risk—which help promote a willingness to cannibalize successful products. In addition, subsequent chapters spell out practices that help in providing incentives for enterprise, instituting internal markets, and empowering champions.

1 Khanna, Tarun, Jaeyong Song, and Kyungmook Lee, “The Paradox of Samsung's Rise,” Harvard Business Review, 89, no. 7/8 (July/August, 2011): 142–147.

2 Fan, Shay, “The Slate: A History of Innovation,” The Next Bench Blog, 2010, http://h20435.www2.hp.com/t5/The-Next-Bench-Blog/The-Slate-A-History-of-Innovation/ba-p/52657

3 Ghemawat, P., “Market Incumbency and Technological Inertia,” Marketing Science, 10, no. 2 (1991): 161–171; Kamien, M. I. and N. L. Schwartz, Market Structure and Innovation (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1982); Reinganum, J. F., “On the Diffusion of New Technology: A Game Theoretic Approach,” Review of Economic Studies, 153 (1981): 395–406. However, a few economists have designed models to show the optimality of cannibalization: Nault, Barrie R. and Mark B. Vandenbosch, “Eating Your Own Lunch: Protection Through Preemption,” Organizational Science, 7, no. 3 (May-June, 1996): 342–358.

4 Hill, Andrew, “The Architecture of a Company Being Built from Within,” Financial Times (April 14, 2011): 16.

5 Ibid.

6 Based on data collected by the author and Deepa Chandrasekaran of Lehigh University.

7 Sood, Ashish and Gerard J. Tellis, “Technological Evolution and Radical Innovations,” Journal of Marketing, 69, no. 3 (July, 2005): 152–168.

8 Oliver, Christian, “Fast Follower Leads the Way,” Financial Times (March 20, 2012). http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/7b622220–6e57–11e1-b98d-00144feab49a.html#axzz20GC2mStm

9 Sood, Ashish and Gerard J. Tellis, “Do Innovations Really Pay Off?” Marketing Science, 28, no. 3 (May-June, 2009): 442–456; Borah, Abhishek and Gerard J. Tellis, “To Make or Not to Make: Stock Market Returns to Make Versus Buy Innovations,” working paper, USC Marshall School of Business (2012).

10 Borah and Tellis, “To Make or Not to Make.”

11 Tellis, Gerard J. and Ashish Sood, “A New Framework to Help Firms Select among Competing Technologies,” Visions, PDMA, Vol. XXXIV, No. 3, 18–23, Oct. 2010.

12 Ibid.

13 This case is based on investigative reporting in Guth, Robert A. “Microsoft's Bid to Beat Google Builds on a History of Misses,” Wall Street Journal (January 16, 2009): A1, A6.

14 “Microsoft's Bid to Beat Google Builds on a History of Misses.”

15 Ibid.

16 Kunii, Irene M., Cliff Edwards, and Jay Greene, “Can Sony Regain the Magic?” BusinessWeek Online (March 11, 2002). http://www.businessweek.com/stories/2002–03–10/can-sony-regain-the-magic

17 Rose, Frank, “The Civil War Inside Sony,” Wired Magazine (February 11, 2003). http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/11.02/sony.html

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Isaacson, Walter, Steve Jobs (Kindle ed.) (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 388.

23 Swasy, Alecia, Changing Focus: Kodak and the Battle to Save a Great American Company (New York: Crown Business, 1997), 21.

24 Rediff Interview, “Innovation Best Comes from People Who Know Nothing About the Topic,” Rediff India Abroad (2006). http://www.rediff.com/money/2006/aug/07kodak.htm.

25 Lucas, Henry C. and Jie Mein Goh, “Disruptive Technology: How Kodak Missed the Digital Photography Revolution,” Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 18 (2009), 46–55.

26 Rediff Interview, “Innovation Best Comes from People Who Know Nothing About the Topic.”

27 Ibid.

28 Lucas and Goh, “Disruptive Technology.”

29 Swasy, Changing Focus, 30.

30 Smith, Geoffrey, William C. Symonds, Peter Burrows, Ellen Neuborne, and Paul C. Judge, “Can George Fisher Fix Kodak?” Business Week (October 9, 1997).

31 Smith et al., “Can George Fisher Fix Kodak?”

32 Tellis, Gerard J. and Peter Golder (2001), Will and Vision: How Latecomers Grow to Dominate Markets, New York: McGraw-Hill.

33 Ingrassia, “Gillette Holds Its Edge,” 1.

34 Glazer, Emily, “Shaving's True Cost? It's All a Matter of Blade Life,” Wall Street Journal (April 12, 2012): B8.

35 Ingrassia, “Gillette Holds Its Edge,” 1.

36 Ibid.

37 Fan, “The Slate: A History of Innovation.”

38 Wikipedia, “HP Slate 500.” Retrieved August 17, 2011, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HP_Slate_500

39 Sherr, Ian, “Tablet War Is an Apple Rout,” Wall Street Journal (August 12, 2011): B1–B2.

40 Worthen, Ben, “HP Needed to Evolve, CEO Says,” Wall Street Journal (August 23, 2011): B1–B2.

41 Nault and Vandenbosch, “Eating Your Own Lunch: Protection Through Preemption.”

42 Deutschman, A., “The Managing Wisdom of High-Tech Superstars,” Fortune 130, 8 (October 17, 1994): 197–206.