CHAPTER 1

The Origins of Value: What People Want Is Not as Important as What They Need

ABUNDANCE AGRICULTURE AND THE ARTS

Somewhere in the mid-eighteenth century, agricultural production exceeded population growth, meaning that surplus farming could replace subsistence farming in many places. The farmer could therefore barter crops in exchange for someone to repair fences, tutor the children, or sing in the evening.

Thus, “value” became highly important. Was someone who planted crops more valuable than someone who tended the animals? Was a plow horse more valuable than a new roof? Could some of the children be released from sunup-to-sundown chores by employing others, perhaps even sending them to school, or the priesthood, or the military, or a convent?

And I'm quite sure that about 200,000 years ago one of our forebears exchanged some flints or arrowheads he had prepared in exchange for a mastodon steak or some hide for clothing. The two parties involved somehow reached an agreement about the value of the transaction and the worth of the services or products.

“Value” represents worth, usefulness, importance, good stuff like that. A “fee” is equitable compensation paid in return for a desired service or product.

Questions? Simple, right?

I was the keynoter at a convention once where a participant in the audience told me that he could make more by billing hourly for his time than anyone could basing fees on value. I laughed and walked away. This isn't a shade of grey, or a debate, or philosophic point. He was denying the existence of gravity or oxygen.

When retailers find sales declining, the smarter ones raise prices, they don't engage in desperation sales. Buyers are willing to pay the higher prices when they perceive those prices denote higher value.

People believe they get what they pay for; otherwise no one would buy a Brioni suit, or a Bentley car, or a Breitling watch. Now, you don't need Brioni, Bentley, or Breitling for attire, transportation, or the time of day. But they do fulfill certain ego needs, certain emotional desires. Nothing wrong with that.

Logic makes people think, but emotion makes them act. When I was confronted with the need for a wrench, sending me to the unfamiliar hardware store, I found three wrenches, all alike, at three different prices. I chose the most expensive on the “emotional” basis that it was probably made from better materials (I had zero evidence of that). Some people will buy a brand name they recognize on that same basis, which is why we'll focus on the relationship between fees and brands later in the book.

When a woman asked me in 1985 if I'd like to have one of the very first car phones in New England (the last four digits were 2468 at my request), I didn't do a cost analysis or ask for references; I told her to get over to my place and I'd cancel my afternoon appointments. Ego needs are quite legitimate and very powerful buying catalysts. Today I carry the latest iPhone in my pocket; it works through my car's sound system (but I wouldn't mind looking into a mastodon steak if possible).

At some point, of course, there was the question of how many days, how much time, how much presence was required, and time became a measurement of value. Yet it's interesting that a field hand might have been paid by the day or a teacher by the lesson, but the great artists were paid by results. Michelangelo, da Vinci, Beethoven, and Mozart were commissioned to create works of art, not to work by the day or to be “present.” Some of these works took years and there were vast gaps between the commission and the fulfillment thereof. Da Vinci was famous for lugging works around with him that were in various stages of completion, including the Mona Lisa. Michelangelo required four years to complete the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, despite the imprecations of Pope Julius who, understandably, wanted to see it in his lifetime.

For our purposes here, and for your purposes in terms of future success, “value” pertains to the quality and power of the results delivered. There is no value in a training program, a book, a focus group, a strategy session, a coaching engagement, unless there is a demonstrable tangible and/or intangible result of quality and pragmatic application. By “intangible” I refer to ego fulfillment, aesthetics, comfort, security, and so forth. Not all value is monetized, and in fact some of the greatest value is intangible, such as an improvement in self-esteem or closer relationships and intimacy.

As we continue, please bear in mind that this type of thinking is a question of “mind-set.” You have to believe that the result is the key, and not arbitrary “deliverables,” those darlings of the human resource crowd, or the time required. Cole Porter, Salvatore Dali, Thomas Alva Edison never worried about the time required to create value.

However, there is a second aspect about this mind-set that is overarching: Charging by a time unit is unethical.

I mean that as harshly as it's written. I read a piece on social media while writing this book from an Australian accountant who pointed out that if you charge by the hour (as most accountants still do) you “run the risk of cheating yourself of greater income.” What he meant is that if you're good and fast, an advantage to your client, you get paid less. If you're slow and inept, a disadvantage to your client, you can make a lot more money.

This is the inherent unequivocal problem with fees based on time units or “showing up”: They abuse your client relationship or they undermine your ability to earn money. Every client deserves fast and quality results, and every professional services provider deserves equitable compensation based on the results they create.

I don't believe anyone ever asked Picasso how long it took to paint Guernica. Some expert valuations place it at a worth of $200 million. That is not a typo. At a $1,000 an hour, an incalculable fortune in Picasso's time, he'd need 200,000 hours to equal the $200 million price by the hour. That's about 22 years. He lived to 91, so perhaps working round-the-clock he might have done it.

That agricultural transformation, as well as ego fulfillment and including great results not based on time, are a function of an abundance mind-set.

THE ABUNDANCE MIND-SET

It's insufficient to possess abundance. One must be willing to use it. We must move from a poverty and scarcity mentality to an abundance mentality. If the farmer with a surplus decided it was best to keep it and protect it for that proverbial “rainy day,” there would be nothing with which to pay for a tutor or fence repair. And some people, no matter what their income or savings or prospects, act as if they're poor.

You've all seen this: the otherwise successful people who never pick up a check, who take modest vacations, who have ten-year-old cars, whose houses need maintenance. These are people continually asking if they “really” need something as an excuse not to spend money on an acquisition. We've all seen elderly people who have ardently saved through their lives only to lose it all in a health crisis or scam.1

I once asked a group of coaching clients at an event what they would do if they unexpectedly gained $600,000 via a client request for work, or a lottery winning, or an inheritance. Most spoke of partial savings, some philanthropy, some personal acquisitions, vacations, and so on. But one woman said to me, “I wouldn't touch a cent of it, it would sit in the bank!”2

Thus, we experience people with significant growth and prosperity who continue to act as if they were desperately trying to gain a foothold, to keep their heads above water. I call the need to change based on true prosperity securing the “watertight doors.”

Figure 1.1 The Watertight Doors

In Figure 1.1 you can see the progression from trying to survive, to being “alive,” to having “arrived,” and finally to thrive. Survival takes pressure off, then “alive” means you have a “going concern,” as the accountants like to say. “Arrive” denotes a brand and recognition within your field, with unsolicited referrals coming your way. And “thrive” is the expert and thought leader, one who sets the paces and is used as a reference point for excellence.

The problem is that many people to the right of my chart still act as though they're on the left, never having been able to abandon old habits and old friends. To transit from left to right, we must be willing to change our beliefs, friends, image, self-talk, expectations, affiliations, and so forth. That's the only way to create “watertight” doors that don't permit us to slide back.

I talk to people too often who tell me in the same sentence that they're having their best year ever but can't afford to invest in their own self-development, or give to charity, or take an unexpected vacation. You may see this as hypocrisy, but I see it as an inability to leave a poverty mentality that enabled them to survive but not enjoy their arrival or beyond.

The abundance mind-set is not merely about money. It's also about time, information, volunteerism, support, and so forth. In other words, an abundance mentality is denoted by generosity. The most successful people I know are also among the most generous I know.

You can begin each day as a long-slow crawl through enemy territory or as having the potential for great opportunity. Thinking abundantly is a mindset and a permanent disposition. It's not a motivational technique or a fad.

Not long ago, so many people burned their feet at a fire-walking (hot coals) session that extra EMTs had to be called! My conclusion is that they just weren't motivated enough! Trodding hot coals does nothing for your life, unless that's the only route to your office. But creating and maintaining a positive and abundance mind-set will enable you to enjoy life, be resilient, and constantly appreciate your own worth for others, which just happens to determine your fees.

WHY YOUR PRESENCE ISN'T REQUIRED

The concept of value is not, therefore, vested in your physical presence, physical work, or even being in view. Value is a function of the worth I place on a product, service, or relationship. Value may be, like beauty, in the eye of the beholder—a season ticket to a 49ers game might thrill one person but cause someone else to say, “Is that on Xbox?” or “What's a 49er?”3

Value can be tangible:

- Increased income

- Larger market share

- More referrals

- Lower cost of new client acquisition

Value can be intangible:

- Improved aesthetics

- A feeling of security

- Greater safety

- More freedom

Some value is society- or community-related, creating normative pressures to appreciate it:

- Better roads

- Faster internet

- More access to quality health care

- Better schools

Some is intensely personal:

- More intimacy with my partner

- Better cooking skills

- Ability to speak a second language fluently

- More respect from colleagues

Value pertains to the importance of something, and is measured in worth, often expressed in equitable compensation. Given the diverse factors noted above, some people see value as a bargain (“I purchased this fine wine for 25 percent below retail prices”) and some as justification for major investment (“The painting is worth $5 million on the market at the moment”). What is the worth of a great vacation or entertainment experience. Those with a scarcity mentality might buy cut-rate tickets to the theater and tolerate obstructed views, while those with an abundance mentality might pay 200 percent of face value to secure house seats.

But note that these are all experiences of one kind or another. A personal guide in Pompeii has to be with you if you're on a walking tour, and is much more valuable than an audio guide as you wander around. (You can't ask questions of an audio guide.) However, the person selling you the house seats needn't accompany you to the theater or even talk to you; it can all be done on the computer.

Whether we are present (e.g., interviewing people and holding focus groups at a client's site) or not (e.g., advising by e-mail, phone, or Zoom), our value is in the results of our project and advice, not in terms of whether we are present or not, in reality or virtually. This book is of value to you, but I'm not reading it to you and you're not paying by the page.

Our clients are best served by quick, accurate resolutions to their issues. But if we charge by the day, for example, we make the most money by staying as long as we can. That is an ethical conflict. Moreover, the client shouldn't have to make an investment decision each time the client feels we may be needed. And our presence is often disruptive, distracting, and costs still more because of travel and lodging needs.

Many professional services began charging by the hour (lawyers still tend to bill in six-minute increments) and have never changed: accounts, designers, attorneys, architects, consultants, coaches, and so forth. However, the smarter ones evolved to understand the concept of their value, not merely their time. What is the value of legal services for a successful acquisition, or an amicable divorce? How valuable are accounting services that proactively can reduce your taxes or arrange for interest-free loans under certain circumstances?

THE IMPORTANCE OF BUYER COMMITMENT, NOT COMPLIANCE

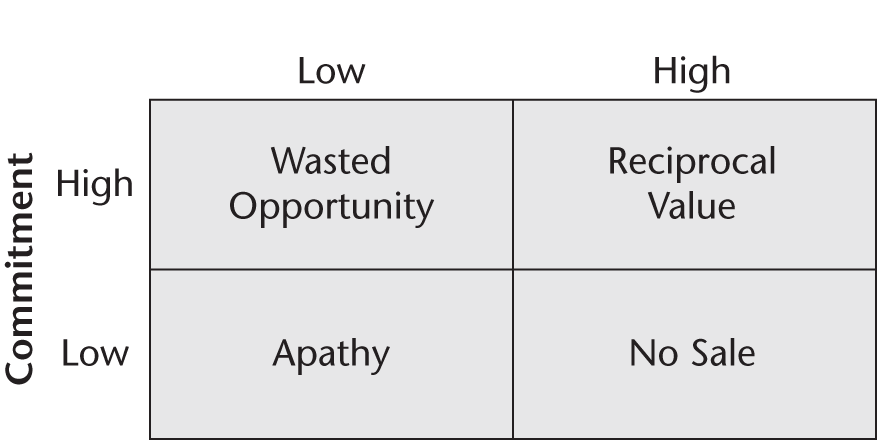

I can prove anything on a double-axis chart,4 but the matrix in Figure 1.2 happens to hold true. As you can see in the figure, the ideal relationship occurs when buyer commitment to the project (and to you) is high and your fee is high. If buyer commitment is high and your fee is low, you are wasting an opportunity. If buyer commitment is low and your fee is low, you will, at best, create an indifferent sale. And when fees are high but commitment is low, you will be shown the door.

My estimate is that most consultants' approaches (whether or not they actually get the business) are in the bottom left quadrant about 25 percent of the time, in the bottom right quadrant about 10 percent of the time, in the upper left quadrant about 60 percent of the time, and in the upper right quadrant only about 5 percent of the time!

That's right: most consultants, including most of you reading this, habitually undercharge for your services and deliver far more than you are receiving in remuneration, considering your contribution to success. You are undercharging and over-delivering, and lest you consider that an exalted position, consider trying to pay your mortgage or 401k contribution with that combination.

Figure 1.2 The Relationships Between Fees and Buyer Commitment

Most buyers comply. That is, they are willing to go along with the “expert,” even if it's sometimes against their better judgment. Or they will delegate you to someone they believe has the technical ability to evaluate your proposition, typically in the human resource department, finance, or legal. (Put these together, and they are an anagram for “no business here.”) Buyers who merely comply may be seen at first blush as easy to work with, but they are actually land mines waiting for some weight to trigger them. That's because they hold the consultant responsible for everything. They believe that you are doing something to them or for them or at them, but certainly not with them.

Compliance is dangerous because the buyer usually takes no inherent responsibility for the project but rather abdicates to the consultant. I've never found a project that a consultant can unilaterally implement successfully, since consultants have responsibility but no real authority. (When that dynamic is reversed, it's the sign of a very poor implementation scheme.)

Consulting projects should be true partnerships between the consultant and the economic buyer. This begins prior to the proposal being signed and is an integral aspect of obtaining high fees. A merely compliant buyer will grudgingly or apathetically go along with the implementation but will do so at the lowest possible fee. The head is involved but not the gut (remember: logic makes people think, but emotion makes them act). Large fees are dependent on emotional buy-in, and that must be achieved in the relationship aspect of the consulting sequence, well prior to the actual closing of business.

This is why patience in formulating the right relationship is more important than attempting to make a “fast sale.” The former is a partnership where fees are academic; the latter is a unilateral benefit where fees are often the main point of contention.

CRITICAL STEPS FOR BUYER COMMITMENT

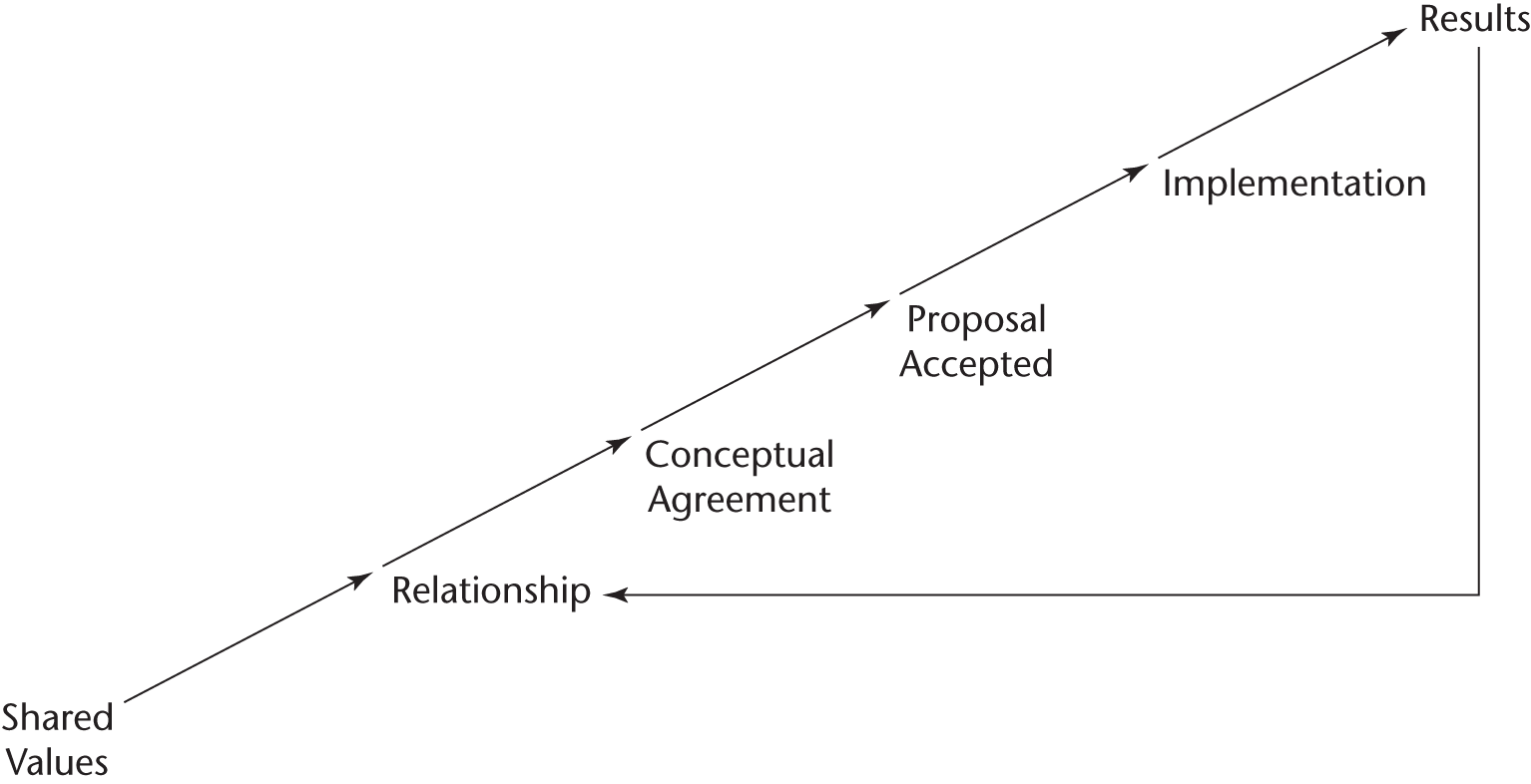

It's worth repeating here briefly the sequence of events in the consulting business acquisition process that engenders the highest-quality commitment; the first three are shown in the graphic in Figure 1.3:

- Shared Values: Those common business beliefs that will allow you to work effectively with the prospect—for example, a mutual antipathy for downsizing or a common belief in the importance of ongoing employee feedback

- Relationship: That level of a trusting interaction in which you and the buyer are comfortable with each other, can be honest (even in disagreeing), and share insights and assistance with each other on a mutual basis

- Conceptual Agreement: Agreement between you and the buyer on the objectives for the project, expressed as business outcomes; metrics, measures of progress toward those objectives; and value, the buyer's stipulation of how he or she and the organization will be better off as a result of those objectives being met

Figure 1.3 Consulting Business Acquisition Sequence

These three critical steps, each dependent on the prior step being successfully in place and addressed as we proceed, will garner buyer commitment. The absence of conceptual agreement will result in either a lost sale or a lousy sale (and the latter is often more damaging than the former).

Fees are dependent on buyer commitment well before a proposal is ever tendered. Note that fees are not even on my chart.

THE BUOYANCY OF BRANDS: HOW BRANDS HELP FEES

The second book in this Ultimate Consultant Series is dedicated to branding for consultants. One of the key reasons for effective branding is to enhance fees.

Fees are (or should be) based on value. That value is always in the eye of the beholder—in our case, the economic buyer. Hence the more value conveyed to that buyer by the most powerful means, the less downward pressure on fees. Effective branding actually creates a fee “buoyancy.”

No CEO ever said, “Get McKinsey in here,” when strategy work was needed, then followed up by saying, “I think they're too expensive.” As they say in the Ferrari showroom when someone asks about gas mileage or insurance costs, “If that's your concern, you really shouldn't be here.”

Ferrari is a brand that evokes certain immediate understandings on the part of the potential individual buyer:

- High cost

- Top status

- High maintenance

- High insurance

- High repair costs

- Unique image

- Personal ego needs met5

You know those things going in, and they are not points for discussion when dealing with a salesperson.

Similarly, McKinsey is a brand that evokes certain immediate understandings on the part of the potential corporate buyer:

- High cost (fees will not be negotiable)

- Top status (no one can say we're giving this short shrift)

- High maintenance (a lot of junior partners will appear)

- High insurance (the board can't complain about quality of the help)

- High repair costs (they will recommend tough interventions)

- Unique image (the cachet alone will raise expectations)

- Personal ego needs met (only the best for the best)

You get my point. The mere power of a brand is sufficient to overcome any resistance to fees and, in fact, often elevates fees merely by dint of association with such brand images as quality, reputation, client history, and media attention.

There is no brand as powerful as your name, although strong company brands can also serve quite well. When a potential client says, “Get me Jane Jones” or “Get me the Teambuilder,” that client is articulating a clear imperative: Don't go shopping, don't compare prices, and don't issue a request for proposals; just get me that person I've heard so much about. (That is far superior to the buyer saying, “Get me a great leadership consultant” and your name is one of several in the hat.)

Brands create an upward expectation of both quality and commensurate fees. No one expects an outstanding person to come cheap. You usually have to convince the buyer of that quality through careful relationship building. But a strong brand shortcuts that process considerably. The relationship building still needs to be done (for reasons of commitment, as noted earlier), but the time required is significantly reduced. The buyer wants to be a partner, wants to follow your suggestions, and wants to participate because your credibility has preceded you.

It's not the intent of this book to explore how to create a brand.6 However, it is vital to understand brand importance in the fee-setting process. Like bank loans being hard to acquire when you need them and easy to obtain when you no longer need them, high fees are most difficult when no one has ever heard of you and you desperately need the income and easiest when you're well known and business is rolling in.

The crime here is that many successful consultants either don't bother to use their past success to create effective brands or have created brands that they don't properly leverage for higher fees. Tom Clancy had never written a book nearly as good as his original, The Hunt for Red October, but he's certainly been paid far more for every subsequent work than for that first effort (and the writers now supporting his brand long after his death). He had been a smart marketer and a hugely successful “brand” (as James Patterson, who's sold a trillion books, seldom writes his own anymore but uses a “co-author”).

Brands create higher fees. And higher fees enable you to solidify the credibility of your brand. That's a great cycle.

CREATING SHARED SUCCESS

Many consultants take the position (out of arrogance or ignorance) of “Let me show you how I'm going to improve things around here.” The success is the consultant's, a sort of largesse provided for the lucky client. There is a certain power in being “the expert” without whom all goes to hell, but there is a huge risk, although not the one that might be apparent.

The apparent risk is that the client might not benefit as desired or, heaven forbid, might actually suffer a reversal of fortune. Remember the physician's sage credo, “First, do no harm.” It's no accident that large consulting firms are being sued right and left in this litigious society. They have not “delivered” the desired results.

However, the greater risk is that even with demonstrable success, the buyer feels alienated, disenfranchised, and apart from it. The fee in this case, despite success, will be paid grudgingly. For one thing, the client is now fearful of long-term dependence and doesn't want to incur huge costs each time the consultant's “expertise” is required to solve another problem. For another, the buyer does not feel the intrinsic ownership and sense of well-being that would emotionally overwhelm any reservations about costs. Third, from an ego perspective, the buyer will feel the need to insert some leverage into the relationship to retain the perceived upper hand and emphasize that the consultant serves at the buyer's pleasure (especially if the results are so visible that others in the organization are talking about them).

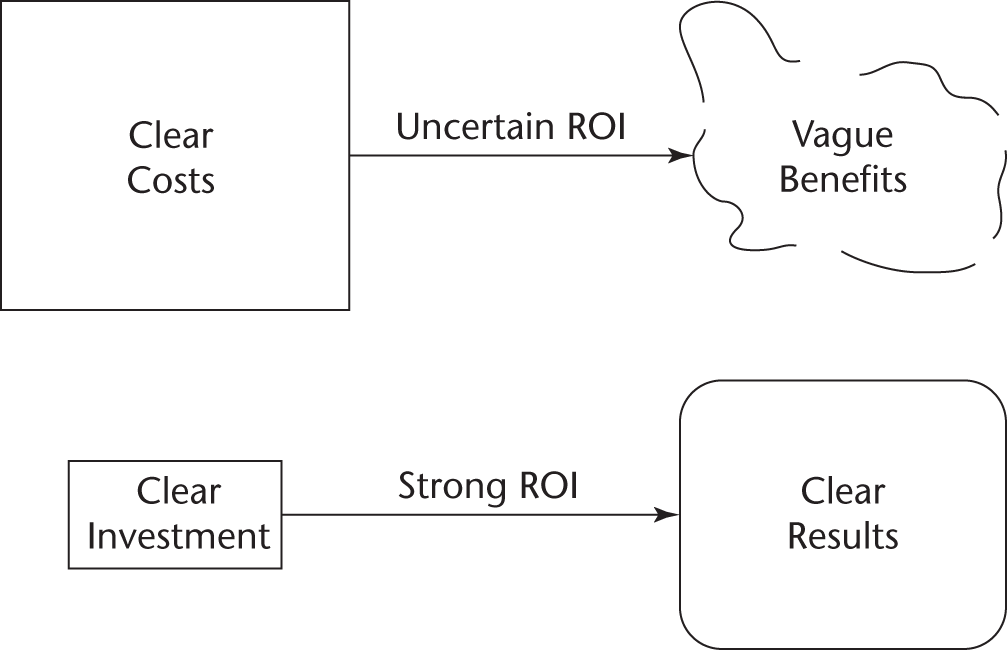

Fee pressure decreases with a sense of shared investment, shared accountabilities, and shared success. Figure 1.4 shows the difference between a focus on a buyer and seller (top) who are locked into a battle over costs with only vague benefits established and two partners (bottom) who have agreed on tangible results where the fee is simply an intelligent and economical investment.

When the buyer simply views the consultant as another vendor providing certain expertise, the cost of acquisition becomes the key focus, because this is a commodity purchase (Who can provide the cheapest computer monitors per our specifications?). However, when the buyer's self-image and role are as a partner in the consulting process, the decision becomes one of return on investment, and the clearer the outcomes (under the conceptual agreement discussed earlier) and the more dramatic, the higher the investment that is justified.

This is particularly true when that investment includes the buyer and key organization people in the partnership. Some of the most successful consulting projects I've landed—and the ones most impervious to fee pressure—are those in which a “virtual consulting team” was formed comprising key client resources and myself. No educated buyer will want to underfund or hedge on that investment.

Figure 1.4 Costs from the Expert Versus Investment from the Partner

These are some of the key factors in shared success:

- A “we” mentality from the first contact with the prospect

- Literature, web sites, and promotional materials that talk about partnering and shared responsibilities

- A formal description of “joint accountabilities” in the proposal itself7

- A strong focus on outcomes and business results, not on tasks or deliverables

- Ample opportunity for the buyer and other key people to take credit and to bask in the success

- Candor in tackling inevitable problems and setbacks

- The consultant's being seen as an object of interest and center of expertise in the field

It really doesn't matter what the organization believes. What matters is what the current and future buyers believe. The danger of consultants trying to “do it alone” is that the client runs through this sequence:

- Who's John Adams?

- Get me that guy John Adams.

- Get John Adams.

- Get John Adams if you can.

- Get someone close to John Adams.

- Get me a young John Adams.

- Who's John Adams?

In a true partnership that focuses on shared success, however, no buyer will try to eliminate one half of the successful combination.

CHAPTER ROI

- One has to develop a philosophy about fees. They are not a “necessary evil” or a “dirty part of the job,” but rather a wonderful and appropriate exchange for the superb value you are delivering to the client. That exchange has a long tradition and represents the highest ethical canon of modern capitalism: agreed payment for agreed value.

- Buyers tend to believe that they get what they pay for, and higher fees actually convey higher quality for most buyers. Higher fees also guarantee a higher level of buyer commitment, and commitment, not compliance, is key to producing a return-on-investment mentality rather than a cost-reducing mentality.

- Brands tend to raise buyers' perception of quality still higher, which is why strategic marketing is an essential aspect of the consultant's repertoire.

- The consultant must anticipate and plan to overcome objections about how other, less enlightened consultants have charged, are charging, or will charge. That is, literally, neither here nor there.

- Leaving money on the table is the equivalent of burning money—you will never, ever recover it, and we are talking millions of dollars over one's career.

- Finally, shared success—understood from the outset and achieved at the conclusion—is vital to the belief in consultant worth as part of a partnership with the buyer.

The One Percent Solution®: Believe in your own value, and build your perceived value in demonstrable ways every day. That is the fuel for the acceleration of fees.8

NOTES

- 1. At least many of these people had some justification in having experienced the Great Depression as a child or World War II.

- 2. I'm happy to report that my coaching has been effective and she currently owns three homes.

- 3. Just in case, the 49ers are a National Football League team.

- 4. In fact, I've written a book with a subtitle, “Give Me a Double Axis Chart and I Can Rule the World” (The Great Big Book of Process Visuals, Las Brisas Research Press).

- 5. I owned three, but I stopped buying them when they ceased making manual transmissions, because the car no longer met my need as a true sports car.

- 6. But do feel free to read the prior book in this series, How to Establish a Unique Brand in the Consulting Profession (Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer, 2001).

- 7. See the author's How to Write a Proposal That's Accepted Every Time (Kennedy Information, 1999).

- 8. Improve by 1 percent a day, and in just 70 days, you're thrice as good.