CHAPTER 8

How to Prevent and Rebut Fee Objections: Since You've Heard Them All Before, How Can You Not Know All the Answers?

I'm constantly aghast at salespeople who wring their hands, rend their garments, and give up the fight when a prospect reacts with the quite normal reaction of “I don't think I need that.” If you've been in the sales arena for longer than a month and haven't heard every imaginable objection, you've been embedded under a rock.

We, as consultants, know what our prospects' objections are going to be before they utter a word. There is no excuse not to be prepared for them. That doesn't mean that we'll be able to convert every single contact into a sale, but it does mean that we should be able to engage the buyer in a more prolonged dialogue and provide ourselves with more opportunities with the decision maker to influence his or her ultimate choice.1

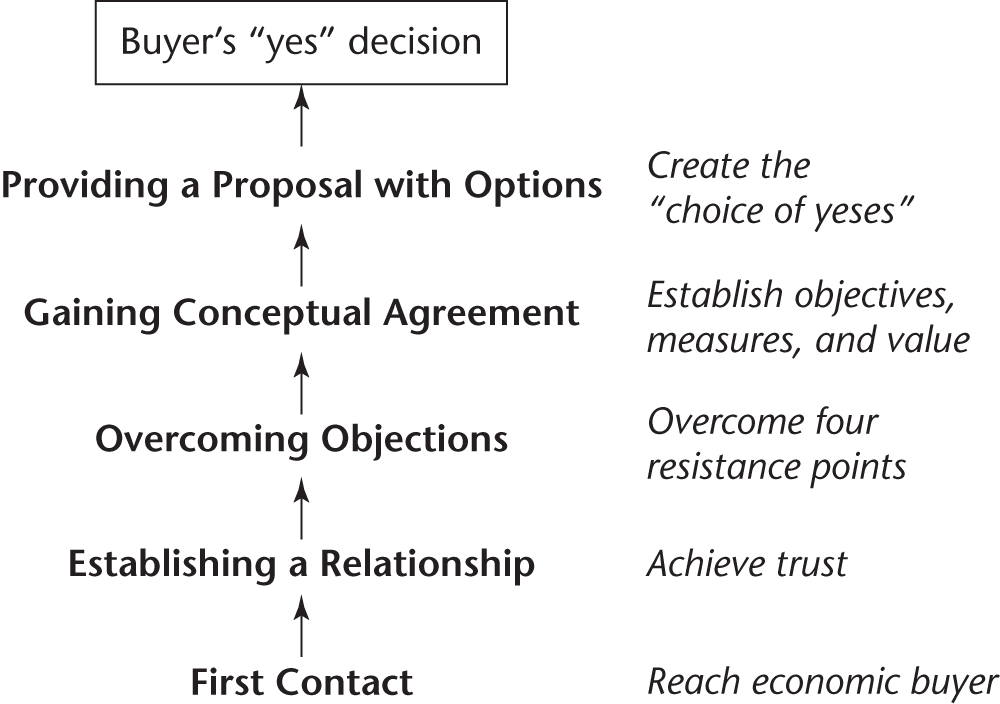

There is a succession of “filters” (see Figure 8.1) that we must negotiate to achieve a positive buying decision. Some require “footwork” and maneuvering, such as getting through or circumventing feasibility buyers and committees to reach the economic buyer. Some require careful questioning and discerning listening in order to reach conceptual agreement.

But one of the most critical and most often bungled steps is dealing with early buyer resistance in the form of quite natural objections and rejections of the consultant's value or potential impact. The reasons include the following:

- We tend to take rejection personally and strive to avoid placing ourselves in a position of possible rejection.

- We provide a sales spiel or other selling retort instead of a true response to the buyer's real objections.

- We don't recognize the generic nature of the objection and offer rebuttals that address our comfort areas and not the client's discomfort areas.

- We panic.

Figure 8.1 Filters to Be Overcome to Reach a Buying Decision

- We don't appreciate that an objection is actually a sign of interest (and apathy is the real killer).

- We actually believe the buyer may be right.

THE FOUR FUNDAMENTAL AREAS OF RESISTANCE

There is a wonderful apocryphal story of a man encountering a friend on the street, searching the ground under a streetlight. “What are you doing,” asks the man.

“I'm looking for my lost car keys,” responds the friend.

“How did you happen to lose them here?”

“Oh, I didn't lose them here. I think I lost them a block away when I entered the restaurant.”

“Then why are you searching here?”

“The light is better here.”

It doesn't matter where your light is better when you're trying to find the reasons for the buyer's resistance. What matters is where the buyer actually lost your reasoning and value.

There are four major generic areas of prospect resistance and potential objection. We know what they are.2 We might as well get good at responding to them.

Resistance Point 1: I Don't Trust You

Perhaps the most common and most fundamentally understandable resistance is that the buyer has no reason to trust the consultant. The credentials might not be strong, the route of entry might be problematic (for example, direct mail or cold call), or the consultant might have other traits that undermine credibility: poor appearance, lack of maturity, poor vocabulary, inadequate promotional materials, and so on.

I don't trust people who spam me to try to sell me web sites. I do trust my accounting firm, which was referred to me by a trusted third party and which carefully considered whether we were right for each other. We've now worked together for 15 years, and I have referred other potential clients to the company.

This is the primary reason that I've advocated “marketing “gravity”3 for all consultants, so that they are known to potential clients, are referred by current clients, and possess an inherent level of trust from a cohesive body of work in the field. Not only is the creation of a name, brand, and reputation a quick route to establishing trust with any potential buyer, but it also considerably shortcuts the process of negotiating the various “filters” between consultant and potential buyer.

When the buyer has no inherent trust—and it's important to understand that this is not created by something the consultant does but rather is the default position unless you actively change it—it is folly to provide “benefits” about money, timing, or value. The client won't listen. And it's impossible to reach conceptual agreement without trust.

It is mandatory for a consultant to establish a trusting relationship with the economic buyer. That will never occur if you choose to work through middlemen.

Resistance Point 2: I Don't Need You

This obstacle means that the prospect may very well trust you and even like you, but there doesn't appear to the buyer to be any need. That might mean that the prospect doesn't see anything requiring fixing or improvement. This is the most common plight of consultants who are merely introduced to a buyer without any specific reason other than “You two should spend some time together.” A friendly buyer does that based on the advice of a third party, but sees no intrinsic need to be filled by the consultant.

This is also why so many consultants have come to me with the same fundamental question: “What do I say after I've said hello?” They've managed to meet a buyer but haven't managed to move the buyer. In fact, many people who don't understand these dynamics make statements such as “I can't understand it—we get along fine, but he doesn't seem to want to hire me!”

What's not to understand? If there is no perceived need, working on greater trust doesn't help. It's incumbent on consultants not to launch arbitrary torpedoes of methodology, technique, approaches, and alternatives, hoping to hit a moving target. It's far better to listen carefully and to ask precise, prompting questions to discover need (see Appendix B), to suggest need, and to create need.4

This phenomenon is why I've strongly suggested that the major value of consultants is to raise the bar to new heights, not just to fix problems. Even the best of organizations can steadily improve; thus there is always a need that can be created, even if there is nothing obvious to be fixed.

The consultant must be able to identify preexisting needs, create needs, or anticipate needs. This is why a “sales pitch” (elevator pitch) about an alternative is completely ineffective.

Resistance Point 3: I Don't Feel Any Urgency

This is the near-legendary excuse that “the timing isn't right.” Every consultant has had hot prospects that could have closed immediately if only the timing had been better. And many of those consultants keep those prospects in their forecasts—or, worse, actually spend the money they're anticipating from the project—for quite a long time.

But the timing never gets better.

If a client doesn't feel a sense of urgency, then enhancing trust levels or heightening need isn't the logical response. After all, I may like you, believe in the fact that we have room to improve, or have a condition that needs remediation. But I've lived with this condition for a long time, and I don't see why I have to do anything (that is, spend money) at this juncture.

Prospects typically resort to “no urgency” or “poor timing” for four reasons:

- When they are afraid of disrupting the organization (“Let's leave well enough alone.”)

- When the return doesn't justify the investment (“I can't see justifying that expense until the problem is costing us far more than it is.”)

- When the perception is that everyone has to put up with this and the prospect is not unique (“This is a ‘necessary evil’ that would be impossible to eliminate.”)

- When there is an intellectual but not an emotional connection to the intervention

In this general resistance area, the consultant must create urgency. This can be accomplished by these methods:

- By pointing out competitive actions that will threaten the client

- By identifying a unique and limited window of opportunity to address the issue (cost of lost opportunity)

- By showing that the prospect is incurring far more damage than perceived

- By demonstrating a far greater return on investment than the prospect believed possible

- By showing that the prospect is not on a plateau but that the condition is actually causing a decline that is increasing in its degree and speed

- By citing personal objectives for the buyer that can be met, creating an emotional stake (“This would create far more attention on your division and your innovative leadership.”)

“Not the right time” is a specious argument because there is always time to devote to business matters—the issue is where it is invested. Time is never a resource issue; it is always a priority issue.

Resistance Point 4: I Don't Have the Money to Pay You

This is the most commonly cited rejection by consultants, and it's mistakenly assumed as the primary objection of most buyers. It is not.

If you've been reading carefully to this point, you've probably come to agree that most resistance is not about money; it's about trust, need, and urgency. If there is trust, perceived need, and sufficient urgency, money can almost always be found. After all, few buyers wake up in the morning and say, “What a beautiful day. I wonder if I can hire Alan Weiss?” And few budgets contain discretionary funds for consultants to be hired for concerns unanticipated, unappreciated, and unheard of.

Most consulting budgets must therefore be created, meaning that the money originates in other areas. It is appropriated from other budgets and other sources. There is never any money, in the sense of quickly available, earmarked funds, for consultants.

So the money objection is the easiest, most common, and most misunderstood. It is almost always an excuse, a cover-up for one of the first three areas not being satisfied. Yet consultants, upon hearing “I'd love to, but we have no budget,” quietly and complacently fold up their tents, leave their cards, mutter “Let's keep in touch,” and disappear into the night.

It's time to have some backbone and buy some floodlights. When a client does say, “We need to do this and I want you to do it for us but I don't have budget,” the consultant can help the client find the funds. When the first three needs (or possible objections) have truly been addressed, the client and consultant can collaborate on finding funds and developing payment terms that are mutually satisfactory (for example, pay half in this fiscal year and half in next or provide stock as partial compensation or take the funds from the annual convention budget and hold the meeting locally rather than overseas).

We're going to discuss some techniques to counter specific points of objection and demurral, but keep them in the context of the four major areas. Your approach should be determined by which of these areas is causing the buyer's resistance at any given time. There may be occasions when all four are working against you, but that is relatively rare. The probability is that one or perhaps two are most on the buyer's mind and that the fourth—no money—is rarely an objection in actuality (although it may be the one verbalized).

If a prospect admits to need, trusts you as a professional and competent resource, and believes the time is right to act, the money will be found. Consequently, the budget is always the worst place to start, because it derails the conversation from the actual and pivotal reasons for the client's rejection.

Worse, focusing on the budget prompts the consultant to lower fees rather than address the true issues behind the resistance. If that's not a double whammy, I don't know what is.

“No money” is as specious as “no time.” There is always money—the question is, will it go to you? This, too, is a priority issue, not a resource issue.

Remember that objections are signs of interest. A truly apathetic, uninterested prospect would ignore you or refuse to return calls or have an intermediary stall you. But objection is a sign of interest and provides a springboard for you to catapult into an investigation of the prospect's reasoning.

Treat objections as opportunities, not threats. And think about this: If there is no time, how did the buyer find the time to talk to you?

MAINTAINING THE FOCUS ON VALUE

Here's an ironclad rule: If you're in a discussion about fees and not value, you've lost control of the discussion. Prospects often want to go immediately to a discussion of costs. It's important to understand the psychology of this tropism. The buyer wants to deal with fees—costs—early because they provide the easiest excuse to be rid of you (and/or not to change). You're not dealing with a real objection but instead with a very effective technique (if not correctly countered) to immediately end further discussion.

The rebuttal to this immediate focus on fees is not to do it. Once you agree to talk about fees, you have enabled and empowered the prospect to focus on the cost side of the equation, not the outcome or value side. If you become a willing accomplice to this tactic, you might as well leave your card and disappear into the night. It ain't going to get better. You must create clear results so that ROI is readily apparent, not ambiguous results where only fees are readily apparent.

Here are the major rebuttals to use when the prospect immediately wants to know what you charge:

- “I don't know what the fees would be, since I don't know what you need or even if I'm the right consultant. Can we spend some time talking about your situation first? That will put me in a better position to answer that question.”

- “It would be unfair to you to attempt a response. We've just met, and both of us need to explore and learn a few things first. Let's table that issue until I can provide a thoughtful proposal, which won't take long if I can ask you a few questions now.”

- “It would be unethical for me to give you a response this early in our talk. I don't know what you need or whether I have the competency to respond to those needs. Let's explore those areas, and then we can talk about value and investment when the scope of the project is clear.”

- “The range will be from $5,000 to $1,000,000. Seriously, I have no idea. Let's explore what's involved and see whether a relationship even makes sense for both of us. If it does, I'm sure we'll find some mutually beneficial way to work together.”

- “What's your budget? [The prospect doesn't know or won't say.] Of course you can't say, and neither can I. We both need to learn more if we're going to have a responsible and cost-effective solution to the issue. So why don't you begin by telling me what you're trying to accomplish, and I'll see how I can help.”

- “Surely you can wait 24 hours to see the fees when I have the full proposal in front of you.”

The key for the consultant is to sidestep this issue using one of my suggested rebuttals or a combination of rebuttals. Under no circumstances should you agree to discuss fees before all the following steps have been completed:

- You have met the economic buyer.

- A trusting relationship has been formed.

- The four generic resistance factors have been overcome.

- Agreement has been reached on objectives, measures, and value.

- Agreement has been reached to entertain a written proposal with a “choice of yeses.”

It may seem that this postpones the discussion for a very long time, but believe me, the refusal to discuss fees any sooner always leads to higher fees.

BORING IN ON THE SUBJECT

It's embarrassingly common for a consultant to negotiate all the shoals and rapids of project negotiations and arrive at the proposal stage only to find the buyer with a near-fatal case of sticker shock. That occurs when the client, despite having stipulated to seeking several millions of dollars of savings and improvements in the project results and believing in the consultant's ability to achieve them also believes—quite seriously—that the fee will be around $5,000, while the consultant's most inexpensive option, which the consultant considers a “good deal,” is $55,000.

How can this happen so far into the discussions and after conceptual agreement? The cause is threefold:

- Some consultants fail to develop a sense about the client's philosophy of return on investment and overall spending.

- Some clients are totally out of touch with investment needs.

- A small business owner will be making comparisons about investing in you or putting the money into a college fund or the next vacation. Those aren't corporate buyers' concerns.

The reasons for the second condition are these (which you can use as red flags should you want to test for willingness to invest early):

- The client has never used consultants in the past and so is totally unfamiliar with investing in external help.

- The client used very inexpensive and inexperienced consultants in the past, which has caused an incorrect “education” and precedent.

- The client has tight cost controls and a zealous focus on the expense side of the business; doesn't see ROI, only costs.

- The client tends to focus overwhelmingly on the short term.

- The client's firm is losing money and in desperate straits.

- The client is a small business owner, weighing personal and business expense needs.

- The client sees the consultant as “too new” or not totally credible and feels that the consultant is getting a chance to prove himself or herself, so the fee can be commensurately low.

When these signs are present, you need to ascertain what the buyer's budget expectations are. Don't forget, few buyers have set aside funds for consultants, so the money has to be found somewhere. And if you're not skilled in determining the budget conversationally, you must find out formally.

Here's how to do that. After conceptual agreement is reached but before the proposal is even created, ask the buyer a variation of the following question: “You've been very kind, and I'm in a position to offer a proposal with some investment options for you. Since there are options for achieving these goals, is there a budget amount you'd like me to stay within?”

Another approach is this: “We've made fine progress, and I don't want to waste your time or mine as we go forward. Is there a budget—or even a rough amount in your mind—that represents the limit of your investment in this project?”

And here's one more, which I call the New York (direct) approach: “We're ready to move to a proposal, but before we do, my experience has shown that it's important to understand any constraints on our approach. What is the budget range you're willing to consider, now that we've reached this level of agreement?”

My suggestion is to ask these questions after conceptual agreement because you will have the best chance to convince the buyer that a significant investment is justified at that point. But do it before the proposal so that you don't waste your time if the buyer's expectations are simply ridiculous. (I call it “pouring concrete” on conceptual agreement.)

There are three common responses to my three questions, and they in turn deserve certain reactions from you:

Common Response 1: “What is this? The wedding reception approach? So the more money I have, the better the reception? I don't want to disclose what I'm prepared to spend.” This usually indicates that you don't have a very trusting relationship. You should respond, “I've come to respect you and don't want to waste your time. My judgment at this point is that the investment range is going to be $35,000 to $65,000, depending on how much certainty you're seeking. Is that in the ballpark?”

If the client tells you to go ahead, then you've prepared the buyer, and there can't be sticker shock. If the buyer says the range is too high, part as friends.

Common Response 2: “Our expectation is that the project should cost somewhere around $20,000.” If that's realistic, respond, “We can work within that, and I'll get the proposal to you tomorrow.” If it's unrealistic, say, “I don't think we can do it for that amount. We're probably talking about $35,000 at the low end to $65,000 at the high end. Do you want to discuss this further?”

This allows for total honesty. The client might say, “Okay, I'm prepared for a slightly worse case, go ahead.” If not, part as friends.

Common Response 3: “We're willing to spend whatever is reasonable to make this happen.” Your reply here should be, “Thanks, I'm sure you'll find the investment well within reason in view of the benefits we've already detailed. The proposal will be here tomorrow.”

Asking about the budget is perfectly fine, provided that you do it at the right time and are prepared for the three types of responses. Here are the conditions:

- You have been talking to the economic buyer all along.

- You have achieved conceptual agreement with the economic buyer.

- You are uncertain of the buyer's understanding of the level of investment required.

Note that if you are speaking professionally in addition to your consulting, and a prospective buyer asks about your appearing at an event, ask very early what the budget is. Many infrequent or novice buyers of speaking services have no idea about fees, which vary tremendously in the field.

Finally, convince the closely held business owner that “competing” interests such as college funds, vacations, philanthropy, and so forth can all be served far better with the business growing more rapidly.

OFFERING DISCOUNTS

I offer discounted fees under certain circumstances, and I'm not talking about returning a coupon or buying a special appliance. I offer discounts when I find that the project calls for phases (not options, which I always provide) and I want to encourage the client to use my help through all of the phases. A phase is a timed step or sequence, each succeeding one dependent on the successful completion of the prior one. Typically, a project might require an information-gathering phase, then recommendations for intervention, then creation of the interventions, then the implementation, and then follow-up and monitoring. While I'd prefer to include all phases in one project, it's sometimes impossible to do so, since you can't predict needs further down the line until earlier steps are completed.

In this case, I suggest offering the client another form of a good deal. Offer the client the rebate of a percentage of the phase 1 fee if you're hired for phase 2, and so on down the line. What's the right percentage? Who knows? But I keep it to 25 percent or below. (The higher the fee for phase 2, the higher the percentage rebate—don't make the mistake of looking at the fee for phase 1 for the rebate percentage!)

Example: The client has agreed to a phase 1 needs analysis among customers for a $35,000 fee. The second phase would be the development of a better customer response system, based on the customer feedback and priorities. You're estimating that phase 2 would be in the range of $125,000 to $175,000. You tell the client that should you be chosen to implement phase 2 of the project, you will rebate 25 percent of the phase 1 fee if phase 2 is accepted within 30 days of the end of phase 1 or prior. That means that you're still netting well over $100,000 on phase 2 while greatly reducing the chances of another consultant being brought in or the client deciding to do it internally.

Of course, if you think that you're a “lock” for the continuing phases, there's no need to offer a rebate, or you can offer just a token one. But I always like to “think of the fourth sale first,” so I believe rebates are a good idea in these situations, particularly with new clients with whom you don't have a track record. If you think of the totality of the several phases as the real project, then the rebates can be reasonable reductions against the very large total investment.

You might want to use the designation rebate or discount or professional courtesy. The key is, it's a tool to be used when appropriate. I find that I tend to offer rebates relatively rarely, but with great effect when I do.

FULL PAYMENT IN ADVANCE

Remember TDTC (total days to cash)? For speaking engagements I require 100 percent paid at the time of the booking, no matter how far in advance the speech will be. (Most speakers bureaus will ask for 50 percent, and then hold on to it, which is why you shouldn't work through speakers bureaus. See my book, Million Dollar Speaking (McGraw-Hill, 2011). If you're dealing with a true buyer, and not a meeting planner, this is no problem.

For consulting work, I always offer a 10 percent discount if the full fee is paid in advance. As mentioned earlier, many organizations have a rule that any discount must be accepted. That's where negative TDTC arises.

If you can't achieve full payment in advance, then require 50 percent on acceptance (not “commencement, which might be weeks or months off), and 50 percent in 45 days. You can always negotiate terms, but start with terms most effective for you.

USING “SMACK TO THE HEAD” COMPARISONS

There are times when the client will balk at a fee, even when you know darn well that the fee is entirely reasonable and the good deal is terrific. You'll also be certain that the buyer can afford it, and the reluctance will sometimes start to get on your nerves. This often happens after a proposal has been presented and you believed that all such contingencies were long since dealt with.

You'll be very frustrated. So the answer is to get a metaphorical large board and smack the buyer upside the head. Here's how you do that. Find comparisons that will embarrass the buyer into giving up his or her resistance. Some buyers are simply maneuvering for a deal; some have an ego that won't be sated until they get a concession; some are transferring other issues in their lives (a fight with a spouse, a lost promotion) to you. No matter. Whatever the cause, don't fall for it. Fight back.

I've found the best comparisons to be the following, but any imaginative consultant can easily add to my list (in fact, it's fun to do so):

- Point out that the client is spending more on copy machine warranties and repair than the total cost of your proposal.

- Demonstrate that spillage and ruined product cost 10 times the proposal's most expensive option.

- Ask what one lost customer a week is costing.

- Ask what the cost of a very bad hire is.

- Cite the cost of each talented employee who leaves the organization (including replacement, lost business, training, succession planning, and so on); don't skimp.

- Ask the cost of the client's most recent gaffe in connection with a failed new office or a poorly received new product.

- Cite what the savings would be if R&D commercialization time were cut by 25 percent.

- Ask what the board of directors' reaction would be if the board considered the cost of the current problems versus unwillingness to make this investment to solve them.

You get the idea. Have these ready, because you never know when you'll need them. The most agreeable and friendliest client can spring an unexpected fee objection, even after conceptual agreement and receipt of the proposal. It's your own fault if you're not prepared to fight back.

There are several sources to use to develop your “smacks upside the head”:

- In your preliminary discussions leading up to conceptual agreement, make some gentle inquiries into the costs the prospective client is incurring in some of these areas. Listen for voluntary disclosures (for example, “Do you know we're spending $175,000 just on software ‘fixes’?”).

- Use internet search engines to turn up statistics and facts on common issues. For example, find out the average costs of turnover, lawsuits, recruiting, and so on.

- Tear relevant items out of your daily reading. The Wall Street Journal and BusinessWeek are forever publishing information on the costs of accounting, legal, computers, and other areas.

- Remember that many of these are generic, and you can use them from client to client. Save your best ones to use in key situations. I'm forever pointing to the copy machine “culprit” sitting in a corner as an example of the client's being willing to spend more money on equipment maintenance than on human development.

- Use your prior client engagements as examples of investments and ROI. The closer to your current prospect in type or situation, the better.

- Provide a calculation of what's lost if no action is taken. Steady bleeding can kill the patient as surely as trauma can.

- Demonstrate that attempting to resolve this internally is impractical and even more expensive (and it always is) because of time taken away from other tasks, turf battles, lack of external best practices, lack of residual talent, and so on.

The embarrassing comparison will take care of most of the flimsy and capricious objections to fees. Sometimes you just have to pack a strong metaphorical weapon.

Don't dignify bizarre positions. Educate the buyer correctly from the outset. Ignore the competition and the competition's poor strategy. Now is the time to be your own person. Your value is unique, not comparable to the competition.

The only person deciding what your profit level is should be you. It's a mistake to allow the buyer to do that, and it's insane to allow the competition to influence it in any way at all. So stop doing that.

CHAPTER ROI

- There are four fundamental resistance points: no need, no trust, no urgency, no money. You must address the correct one. Seldom do all four come into play, and lack of trust is usually the fundamental problem. Lack of money is usually a red herring because it's fundamentally untrue. Money is a priority, not a resource.

- Always focus on value, not fees; otherwise you've lost control of the discussion. Don't hesitate to ask about the buyer's intended budget, especially if certain red flags appear during early conversations.

- Offer rebates or discounts on multiphase projects, when such phases are truly called for and are in the client's best interests.

- Offer discounts for payment in full upon acceptance.

- Prepare yourself with embarrassingly harsh comparisons for times when an otherwise agreeable buyer has fee issues that you know should be brushed aside.

- Remember that an objection is a sign of interest and provides you with an opportunity to further your progress.

- Ignore the competition, since neither the buyer nor the competition should establish your profitability levels.

- Don't give off “deal vibes.”

- Remember that most of the fee-setting dynamic is actually under our control and influence, and you should guard against sacrificing this strength.

- The best way to support high fees is first to believe in the value you're providing and then to convince the buyer of it.

There is no such animal as a “new” objection. We've heard them all before, every one. If the prospect has successfully rebutted your position, the buyer is simply better prepared than you are, and you haven't established a “good deal.”

NOTES

- 1. Once again, I must emphasize that this chapter and its techniques apply only when dealing with the economic buyer.

- 2. The origins of these four areas are murky, and many people take credit. I first heard them from Larry Wilson, the founder of Wilson Learning, in the early 1970s. His collaborator, I believe, was Dr. David Merrill.

- 3. See the first book of this series, The Ultimate Consultant, for details on creating marketing gravity.

- 4. No one “needed” frequent flyer programs, global positioning systems, or drive-through banking and burgers, but we certainly need them today. A luxury tends to become a necessity after just one successful use!