CHAPTER 4

How to Establish Value-Based Fees: If You Read Only One Chapter …

Ever since I began promoting value-based pricing for consultants (and the variety of other occupations and professions that have sought to heed the call) nearly 30 years ago, I've been asked one question consistently by a minority of the acolytes: “What formula should I use?”

That, of course, is the million-dollar question. Fee setting is art and science, and mostly the former. Consequently, the engineers, architects, and other highly structured among us have had to be revived when told that there is no magic formula. However, that's not to say that there aren't excellent ways to create fees based on value, if you're willing to be flexible, confident, and diagnostic.

So if you haven't rushed to get your money back after the first two paragraphs, I can be of considerable help. In fact, I'm going to be very explicit in writing about the creation of value-based fees. But please keep these precepts in mind:

- The idea is to create high margins, not merely high fees. That way, you can afford to be less precise about fees, since the margins will allow for plenty of flexibility.

- Value is in the eye of the beholder. There is no law, nor any ethical imperative, that says that you must charge two clients the exact same amount for the same services. First, the services are rarely identical. Second, the value to those respective clients will always be different. You are not selling toasters.

- The fact that you could do something for less money or that you could do more for the same amount of money is irrelevant. The only relevant facts are: Are you meeting the client's objectives, improving the client's condition, and delighting your buyer? To answer that, you virtually never have to provide details of every single service, every scintilla of information, or every day of your life to do that.

I also want to emphasize that fees are means to more important ends. Wealth, to me, is about discretionary time. You can always make more money, but you can never make another minute. Those daily 24 hours are all you have.

Some of you can create wealth with less money than others. It depends on your lifestyle, age, career trajectory, personal values, family size, and many other factors. But never lose sight of the fact that fees are a means to create wealth, and wealth is a function of your freedom to allocate time to important personal objectives and needs.

I've met too many people running around to make money who are actually eroding their wealth.

CONCEPTUAL AGREEMENT: THE FOUNDATION OF VALUE

Consulting is a relationship business. Trust is essential to relationships. When a buyer trusts you and you trust the buyer, you are in a position to acquire the three essential building blocks for a value-based project:

- The business objectives to be met

- The metrics or measures of success to assess progress

- The value to the client of meeting those objectives

Signs of trust: How do you know you've achieved trust with a buyer? The buyer …

- Doesn't allow interruptions by e-mail, phone, or secretary.

- Asks for advice on the spot.

- Reveals confidential information.

- Laughs and uses humor.

- Looks you in the eye.

- Asks for examples to prove your points.

- Accepts pushback and disagreement gracefully.

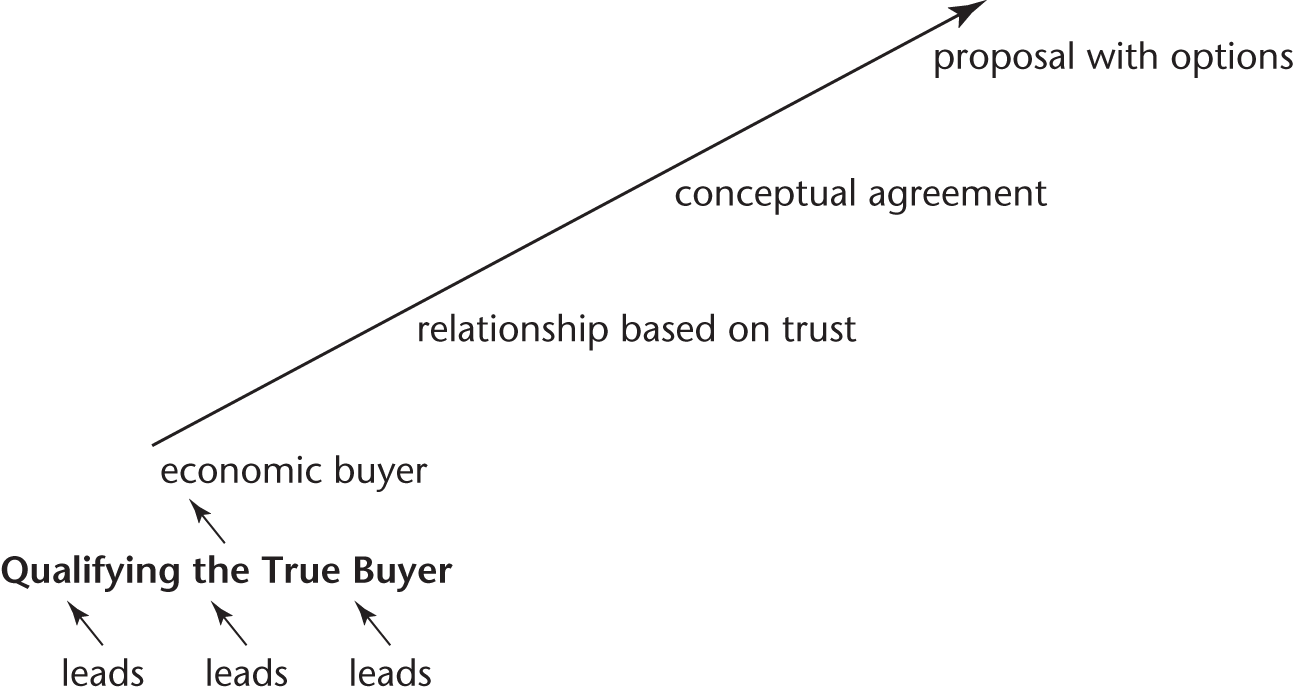

That's it. That's all you need from the client to set a fee based on value. And you can only obtain that from the economic buyer. The sequence here is simple and straightforward, and also immutable (see Figure 4.1).

As you can see in the figure, our marketing efforts create leads, which we pursue and qualify to find the true (economic) buyer—the person who can write a check for our services. We then establish a relationship with that buyer so that we can gain conceptual agreement about the three criteria above. Without the economic buyer, the discussion is irrelevant; without a trusting relationship, the important information is unlikely to be shared or even forthcoming; and without conceptual agreement, we are unable to establish the value as perceived by the client, which is the key input to determining our own fees.

Figure 4.1 The Value-Based Fees Sequence

One last time, then:

- Objectives: Business outcomes (for example, higher sales, better teamwork, faster time to market) that are essential for the project to deliver for the client

- Measures: Objective or subjective (anecdotal) criteria that will indicate progress and, eventually, completion for client and consultant

- Value: The demonstrable organizational or personal benefit stipulated by the client as representing the actual improvement in the client's condition

I'll provide some “formulas” for this at the end of this chapter, but it's imperative that you understand the underlying rationale first. The economic buyer must agree to outcomes, measures, and value of the improvements in collaboration with you prior to setting fees. If you accomplish this, your proposals will be accepted more than 80 percent of the time (although you'll probably submit fewer proposals than you do now). If you ignore this, your chances of having value-based proposals accepted are less than 5 percent.

Here's an example for our purposes:

Project

- Improve retention of new employees in a zero-unemployment, highly competitive environment

Objectives

- Current rate of new employee turnover (32 percent) lowered toward the industry average (22 percent) over one year's time

- Hiring process improved so that fewer poor candidates survive to the third round of interviews

- Causes for high turnover understood and patterns traced to relevant sources: interviews, orientation, training, mentor, supervisor, and so on

Measures

- Monthly retention report and turnover statistics

- Exit interview analysis

- Survey (to be created) for new hires to accept and reject company offer letter

- Six-, 12-, and 18-month survivor rates

Value

- Current turnover costing $545,000 annually in actual salary, benefits, and related expenses

- Estimated cost of lost work, poor productivity, overtime, and related costs until vacated jobs are ultimately filled by qualified and trained replacements: $2.6 million annually

- Estimated cost of “failure work” in senior management interviewing candidates who should have been eliminated at lower levels: $350,000 annually

- More attractive as an “employer of choice” so recruiting costs decline

- Improved hiring with better candidates reduces training costs

- The better that employees talk about us, the better our media coverage and publicity

In my basic example, this client is spending about $3.5 million on an inadequate and ineffective hiring process. And that's every year. We'll return to this example once we've establish a few more basics. But note that the economic buyer has provided these numbers in discussions with the consultant.1

Here's a second example:

Project

- Coaching the president of a $450 million division

Objectives

- Masters the ability to influence and impress the press and outside directors

- Creates a positive, nonthreatening environment for subordinates' ideas

- Establishes a succession plan for officers with three-deep bench strength

Measures

- Outside directors comment favorably at meetings on communications

- Positive press stories appear monthly; negatives decline

- Regular meetings are established for purely innovation and creative thinking

- New services and product development expand at a greater rate

- Plans are in place with candidates, and there are empty slots for outside recruiting

Value

- More investors, stock price is higher, board approves more funding

- Growth initiatives, funded properly, provide a competitive edge

- New ideas boost market share and publicity in the media

- Decreased recruiting costs, higher retention of top people

- Improved succession planning process improves productivity of those seeking higher positions

- More positive environment reduces absenteeism by 10 percent currently costing us $2 million per year

Even with a “simple” coaching project, you can create true value-based projects with no reliance on how many days you spend or how much access there is to you. The results and commensurate value are the keys.

A hint on value: “Profit” would seem to be an objective and also the value: more profit. However, ask what the impact is of achieving more profit, and some answers are:

- Pay maximum bonuses

- Hire more help

- Pay down debt

- Increase R&D investment

- Pay higher dividends

- Make an acquisition

You can see that the objective of more profit, as simple as it is, can generate a great deal of value that will justify much higher fees.

ESTABLISHING YOUR UNIQUE VALUE

The examples show how to establish value in terms of buyer needs. A second major component of value, however, can be ascertained without the buyer's involvement, and that's your uniqueness and personal contribution.

There are three questions that you should answer in every single engagement, prior to establishing fees:

- Why me?

- Why now?

- Why in this manner?

Why Me?

If there are hundreds of consultants who can do the work in question and provide the value the client requests, you are less valuable to the success of the project. But if the number of consultants who can do the work is limited, your value increases. This is basic supply and demand mentality, but in this limited instance, it works.

Here are some components of this question that can help you determine whether you are uniquely valuable or simply another fish in the school:

- Is the buyer talking to other consultants? If so, to a limited range or a great many?

- Do you possess some unique expertise or history (you “wrote the book,” you once worked in the industry, you worked for the buyer in the past, or the like)?2

- Have you been referred to the buyer by a trusted source?

- Are you known within the industry, or do you have a unique reputation?

Are you at the right place at the right time (you're local, you're available to start immediately, and so on)?

Ask yourself whether you bring some inherent value that others can't, whether by design (a book you've written) or by accident (you're the only one who can begin next week). Sometimes it's as important to be lucky as it is to be good at what you do.

Why Now?

Is there some special value about this juncture that needs to be factored in? After all, there is often a reason why the discussion is being undertaken today and not six months ago or six months from now, and that reason is often desperation!

Here are some component questions:

- What if the client were to do nothing? Would the situation be stable or deteriorate still further?

- Is there a limited window of opportunity during which gains must be made or they will be lost?

- Has something occurred that has increased the urgency significantly (for example, the CEO has said, “Get it done!”)?

- Are certain conditions in place that need to be capitalized on or they will be lost (for example, a competitor's temporary misfortune)?

- Is there funding available that will disappear if not used (often the case at the conclusion of a fiscal year)?

When a prospect contacts you, there is always an implied urgency. The key is to determine just how great it is or to increase it through your relationship with the buyer. Build on that urgency, don't dissipate it!

Why in This Manner?

Hiring a consultant is hardly a default position, much as we all wish it were. There must be compelling reasons in favor of such a hire if the buyer is bothering to talk to you (irrespective of whether the buyer reached out to you or you to the buyer).3

Here are some additional questions:

- Why aren't they doing this internally?

- Have they tried this in the past and failed?

- Have they used other consultants in the past, and if so, with what result?

- Why is this buyer the one sponsoring this project?

- Who else is involved in this project and why?

By determining special circumstances, you'll be in a position to establish your ability to contribute to those special needs.

In establishing your own unique value, you have another important input to your fee determination. (Note that many of the questions in these three areas may be answered in your relationship building with the buyer. Keep them in mind—even written in your notes—as your discussion progresses.)

Note that if a buyer really wants something done and has not been able to accomplish it internally over a period of 30 days, it is probably never going to happen without outside help.

Here is a simple test that might scare you into value-based fees. Draw three columns. Label the first one “Strengths,” the second one “Transfer Mechanism,” and the third one “Results.” Now, in column one, write down your five greatest strengths (good listener, M.B.A., international experience, outstanding writer, and so on). In the second column, write down the main transfer mechanisms you use to convey these strengths to the client (workshop, coaching, consulting, writing, facilitating, and so on). Finally, in the third column, write down five typical results your clients derive from working with you (higher profit, less attrition, reduced stress, better image, and so on).

Now step back and take a look. You are probably charging for the first two columns (your credentials or your time and materials), but not for the client results. It's time to change your focus. You are over-delivering and undercharging.

At this point, you have two excellent sources or indicators of the contribution you are providing to the client's improvement:

- The stipulated value that the successful completion of the project will deliver to the client

- The unique qualities that you, personally, bring to the equation to ensure that those results are met and exceeded

It's now time to appreciate the extent of this mutual “good deal.”

CREATING THE “GOOD DEAL” DYNAMIC

Customers buy cheap pens and expensive cars for the same reason: The purchase makes sense in terms of what they care to invest at that moment for transportation or writing. The pen may be easily lost on the job and is used only for internal signoffs on inventory, so the quality doesn't matter as long as the loss isn't too great when the pen inevitably disappears. In that case, 19 cents makes sense.

The car may cost $125,000, but there are few like it, you feel good in it, and you've always wanted one. You can now afford it. The emotional gratification more than compensates for the difference in the basic cost of transportation that could be saved with a less expensive vehicle.

In either case, it's a “good deal” for the customer. You have to make a “good deal” for the buyer. Note that this is more than merely a return on investment. That's because good deals are based on visceral and subjective needs as much as on analytical and objective needs (which is why you always want to stay away from the obsessively detailed denizens of the purchasing or procurement department). Focus on these “good deal” factors while building your relationship and establishing conceptual agreement (and find out which are most crucial to your buyer):

- Responsiveness (a plus for solo practitioners)

- Referral source (the transferred trust from the person referring you)

- Speed of completion

- Transfer of skills so that the client can replicate

- Using an “authority” or acknowledged “expert”

- Documentation

- Involvement of client personnel

- Confidentiality, nondisclosure, noncompete restrictions

- Use or transfer of proprietary material

- Guarantees and assurances

- Industry knowledge or experience4

- Accountability for tough decisions (you are the “black hat”)

- Ability to travel and visit sites

- Technological compatibility

- Safety (malpractice insurance, liability insurance, and so on)5

- Ability to work remotely when necessary or of advantage.

Not all of these issues will apply. But you won't know unless you check for them. Also, you'll note that “fees” or “costs” are never mentioned as part of the “good deal” evaluation. That's because the good deal is based on value and not on fees. At no point are we attempting to establish a good deal on the basis of lower price, because a good deal must benefit both parties, and lower fees do not benefit the consultant. Consequently, fees should not be a part of this list.

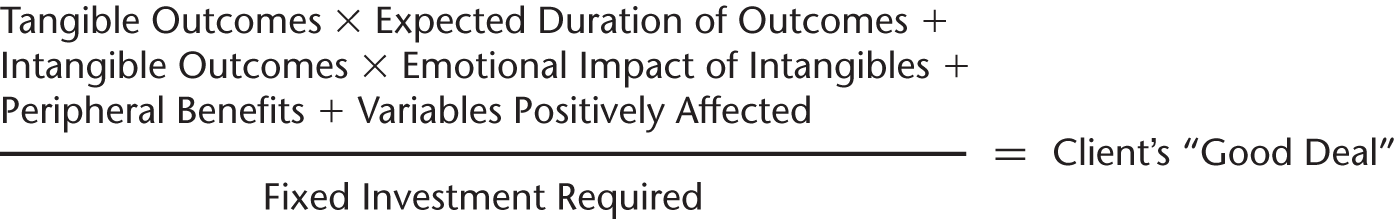

The “good deal” equation for the buyer can include any or all of these variables:

- Duration: The benefits of the project are annualized and forever, while the fee is one time and fixed.

Figure 4.2 The “Good Deal” Equation

- Skills Transfer: The client's people will be able to do this themselves in the future, not only solving the immediate problem but also creating an internal capability for future problems.

- Leading Edge: The client will be assuming a leading-edge position in the industry, marketplace, community, or other environment; above and beyond the issue, the perception and image impact are substantial.

- Control of One's Destiny: Just by dint of doing something—hiring you—the client has extricated the organization from the morass; almost any action can have a positive effect,6 even if results aren't immediately appreciated.

Ultimately, the equation might look like Figure 4.2.

The key is this: Don't seek to lower the divisor by lowering fees; seek to increase the dividend (the benefits and peripherals) so that the quotient—the good deal—is maximized.

THE INCREDIBLY POWERFUL “CHOICE OF YESES”

No client should ever have to make a “go or no-go” decision, yet that is exactly the narrow box that most consultants force on their buyers.

The psychological shift from “Should I use Alan?” to “How should I use Alan?” is enormous. The buyer, in the latter instance, actually enters into a collaboration with you to determine how best to apply your talents and use your contribution. The former, a binary choice, is a sales proposition; the latter, a pluralistic choice, is a partnership proposition.

Another powerful effect of options is that they relentlessly drive fees upward. When confronted with three options, each one promising higher value for the client, the buyer will tend to move at least to the second and often to the third. This can't happen with a “take it or leave it” proposal. Buyers may seek to lower fees, but they also are driven to maximize value.

Here is a brief example of options used in a project involving gathering employee feedback on desirable benefits to retain talent.

- Option 1: We will conduct focus groups throughout the company, representing about 15 percent of the population. The value of these includes “self-sanctioning” groups, which will separate a “one-off” opinion from the prevailing opinions and also allow for follow-up and causal questions.

- Option 2: We will also provide one-on-one interviews with about 5 percent of the population. This provides the opportunity to bolster the focus groups with confidential opinions, drawn at random, without exposing the individual to a larger group. People are often more candid in this situation, particularly those who are relatively unassertive in groups.

- Option 3: We will provide a paper-and-pencil or Internet survey for all members of the population. This will bolster the other options, providing every employee the opportunity to provide feedback on a confidential and anonymous basis. Note that similar patterns that emerge from the three diverse avenues will be highly valid and most reliable.

- Option 4: We will compare the results of whatever options you choose to benchmark studies we have conducted for other organizations, which will also give you a relative insight into your employees' desires and complaints compared to a wider general population.

- Option 5: We will provide a series of workshops for your key managers on how to deal with, react to, discuss, and take action on the results of the studies just described. It's imperative that you have a plan in place to respond rapidly and accurately, without committing yourself to inappropriate solutions.

In this example, the first option (based on the overall value of the project to employee retention) might be priced at $45,000; the second (which includes the first) at $65,000; the third (which includes the first and second) at $95,000; and the fourth at an additional $35,000, regardless of which of the first three options are chosen. The fifth might be an additional $45,000. The buyer is in a position to determine whether to take the “risk” of a single avenue of feedback (which, if only one, you determine is best as a focus group) or whether to minimize that risk with other options, including preparing the management team for how to deal with that feedback (option 5). The decision as to whether to provide for management team training to accompany, say, option 2, is a far cry from deciding whether to proceed or not.

Such is the power of options. They can be used at any point in the sale (for example, “We can have a conference call this afternoon, I can call you alone tomorrow, or I can visit you on Monday—which do you prefer?”) but are especially key in the proposal when providing for a basis for fees.

Once you've established a general fee range for your contribution based on the value generated (all the factors discussed previously in this chapter), you can then spread them across a “choice of yeses” to engage the buyer in the best outcome for the client.

Here's a terrific hint for getting a fee even above the buyer's stated budget. When you provide the options, cite two that are within the budget and one—with even greater and perhaps irresistible value—above the budget. A client who can “find” $175,000 for a project can “find” another $50,000, if warranted. You never know until you ask. No client will ever say, “Be sure to quote me something above my budget.” But with the “choice of yeses” approach, you can justifiably do that by providing options within the budget and an additional one that happens to be over the budget but also provides far greater value.

If you don't believe that this approach will work, consider how many times you've bought extras for your car, computer, phone, garden equipment, pool, or other possessions that you scarcely wanted at the time but then realized you couldn't live without. If the manufacturer or catalogue or store clerk hadn't brought them to your attention, you still wouldn't own them.

Here are 10 guidelines for options, or the “choice of yeses”:

- It's fine to discuss possible options during conceptual agreement, but never assign any fees to them, ever. Simply impress on the buyer that he or she will have choices to make with varying degrees of value and protection against risk.

- Don't “bundle.” You're better off “unbundling.” Most consultants don't have options because they place every single thing they are able to deliver in their “go or no-go” proposal, as if that's the only way to justify their value. If you call a plumber to fix a leak, the plumber doesn't also suggest caulking the tile and updating the heater for the same fee.

- Keep a good distance between options. You don't want a mere $5,000 of separation. Each one must represent significantly more income to you.

- Commensurately with option 3 in the example, make sure that each option clearly provides additional unquestioned value to the buyer. Simply promising more of something or greater frequency does not add value; it merely adds time and materials. For instance, in the sample list of options, there is no option for additional focus groups or interviews. Each option is clearly distinct.

- Some options may include prior, lower-value ones, and others may stand alone no matter which prior option is chosen. In the example, options 1, 2, and 3 are mutually exclusive, each higher one containing the former; but options 4 and 5 can be combined with any of the first three.

- Cite your options formally in your proposal, under a heading such as “Methodology and Options.”7

- Don't attach fees to the options. Cite the fees separately in the proposal under a heading such as “Terms and Conditions.” This is because you want the buyer to focus solely on the value of each option and not immediately connect it with investment. Let the buyer make a mental choice prior to introducing the fee.

- If a buyer says, “I like option 3, but I only have the budget for option 2,” reply, “Fine, then option 2 it is.” This is not a negotiation.

- If a buyer asks for a slightly lower fee associated with a particular option, reply, “Fine, but what value would you like me to remove?” Never decrease a fee without decreasing perceived value.

- Keep your options relatively simple. This is not rocket science. And be prepared to show the differences in value (or the decrease in project risk) as you work your way up the choices.

By the way, apply this process to all of your decisions. Don't decide “to go to the mountains or to the ocean” for vacation, decide on “the best vacation destination.”

SOME FORMULAS FOR THE FAINT OF HEART

I'm always being asked, “Well, you must really estimate days, right?” Wrong. I only estimate client value and my contribution to it.

I'm aware, however, that many of you will prefer help in the form of analytical science until the more intuitive art kicks in. (Don't forget that there is nothing wrong or unethical about the art form of value-based fees so long as the client believes that the resultant value more than justifies the investment in your help in gaining it.)

So for the first (or maybe third) time anywhere, here are a formula and some other criteria for establishing value-based fees. While the engineers in the audience won't be pleased (“What's after the fourth decimal place?”) and the lawyers will be discomfited (“What, exactly, do you mean by a ‘fee’?”), I think the rest of you will at least be happy with the framework.

The Step-by-Step Choice of Yeses

- Step 1: Establish the value with the economic buyer in the conceptual agreement phase, after ascertaining objectives to be achieved and the measures of progress. (Questions to ask for the conceptual agreement components appear in the appendices.)

- Step 2: Establish your own value based on your uniqueness (why you, why now, why in this manner).

- Step 3: Create your options, clearly delineated by increasing value. They may be cumulative or mutually exclusive.

- Step 4: Given the value of the project, estimate a profound and significant return on the investment, working backward. In other words, if the buyer has stipulated a $2 million savings annualized, then a return of 20 to 1 on the first year alone would be represented by a $100,000 investment.

- Step 5: Create your “choice of yeses” using that conservative 20-to-1 return rate as your least expensive option. Increase your other options by a factor of a minimum of 20 percent. In this case, option 2 would be $120,000, and option 3 would be $144,000 (20 percent above option 2).

- Step 6: Now go back to step 2. If your own unique value is high on the why me, why now, why in this manner scale, add another 20 percent to each option. If your uniqueness is moderate, add 10 percent. If your uniqueness is low, don't add anything above the step 4 calculations.

- Step 7: Look at the project objectives and value to the organization in their entirety, and then review your fees resulting from the first six steps. Ask yourself, “Is this a good deal—a bargain—for the client in view of the value, and is it a good deal for me in terms of large margins? If not, adjust up or down, but by no more than 15 percent. Then submit it.

- Step 8: Stop worrying. You'll close about 60 to 80 percent of these deals, which is better than your prior rate (don't lie) and at higher profitability.

If you must use a formula, fix it at 20 to 1 or better—in other words, 10 to 1 is just fine. Bolster your case with these beliefs (mainly for yourself):

- The client is probably spending more on warranties for copy machines and ruined postage than for your project.

- The value to the organization, if anything, is probably understated and conservative.

- Your fees are highly conservative (actually, a 5-to-1 return would be a great investment).

- You've probably underestimated your own uniqueness for this client.

- The value is based on first-year returns. The annualized basis would probably represent a return of 100 to 1.

- It doesn't matter whether you could have done it for $20,000 less or the client would have paid $20,000 more. The margins are still terrific for you, and the benefits still terrific for the buyer. That is all that matters.

If it appears that the toughest sell is to yourself, you've read between the lines quite accurately.

The key to even this formulaic approach is to work backward from the ultimate client value through your unique contribution to the current fee schedule spread over options. Do not work forward, trying to calculate the amount of time, number of days, volume of deliverables, or variety of tasks. They are commodities and, no matter what margin you add to these activities and commodities, it will be minuscule compared to your margin for a truly value-based approach.

The most conservative and even timid value-based approach will be far more lucrative to you, while highly attractive to the buyer, than the most aggressive time-and-materials calculation. Stop selling yourself short.

The formula presented here is meant as a “halfway house”—enough science to get you through until you've mastered the art form and it becomes second nature.

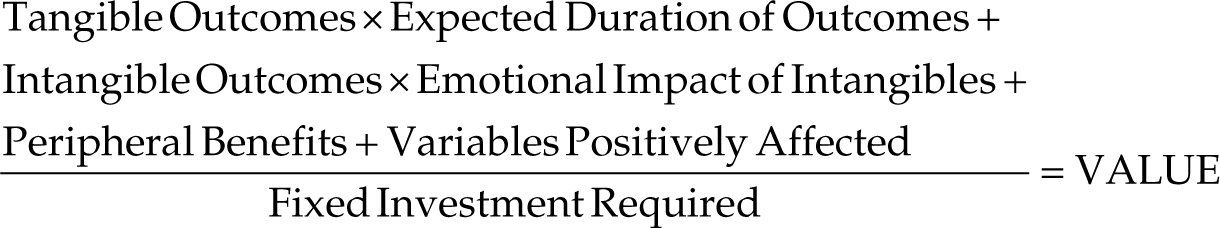

Finally, Figure 4.3 is a strategic and conceptual “formula” for those who are really enthused by the idea of value-based fees and ready to try them:

The tangible outcome and its annualized duration; plus the intangible benefits and the worth of those, emotionally, to the buyer; plus the peripheral benefits (such as being seen as thought leaders) times the number of people who will appreciate them—all of this divided by the investment—equals the value. How can you not demonstrate a huge ROI?

A few words about “peripheral value” and “imputed value”: There is every reason for you to review the objectives and resultant value with your buyer and recommend other value that he or she might have missed. For example: If you cross-sell more products and services, won't you be able to reduce your specialized field force to fewer generalists? If you increase retention, won't you save fees on search firms? If you acquire state-of-the art technical help, won't you reduce “failure work”?

Figure 4.3 Strategic and Conceptual Formula

CHAPTER ROI

- Conceptual agreement is at the heart of the value-based billing process. Any time invested in gaining conceptual agreement, based on a trusting relationship with a true economic buyer, will actually speed the sale at higher margins.

- Your own uniqueness is an essential component that only you can calculate. But it's as much based on self-esteem and self-belief as it is on any pragmatic background or history.

- The reciprocity of the “good deal” creates the win-win dynamic. The client deserves a good deal, but so do you. One is incomplete without the other.

- The “choice of yeses”—options—is the key tactic in moving a buyer to a consideration of value-based fees, and the propensity will be to move upward through increasing value. Never submit a proposal without options of distinctly different value propositions.

- You have an internal assessment about your own worth that you can calculate.

Use the fee formula until you get comfortable, then let the art overtake the science. Remember that you never have to justify your fee basis to a client, and only low-level people will usually make such a demand. You only have to demonstrate the value of the outcomes. Fee setting is a time to be aggressive, not defensive. If you can't articulate your own value, you can't very well suggest value-based fees. Look in the mirror, and practice on the toughest buyer of all. The first sale is to yourself.

NOTES

- 1. See Appendices A through F for examples of the questions that can be used with the economic buyer to establish objectives, measures, value, and so on.

- 2. See my Accelerant Curve and your “vault” items.

- 3. I want to emphasize that my remarks pertain to true buyers. Gatekeepers, trainers, human resource people, purchasing agents, and others will often reach out simply to “shop” and compare prices. These approaches are not designed for such contacts. The only thing to do with those contacts is to use them to reach an economic buyer.

- 4. Although I'm not an advocate of industry specialization, if you just happen to have worked in the field, you probably have an advantage if you position it correctly.

- 5. For example, a consultant cannot work for Hewlett-Packard without providing evidence of an in-force malpractice insurance policy.

- 6. The classic case being the near-legendary Hawthorne studies, which showed that raising the lighting positively affected performance, but so did lowering the lighting. It was the attention, not the actual light setting, that mattered in terms of productivity. Moreover, the study was flawed because of a lack of creation of both control and experimental groups.

- 7. For a formal template and illustrations, see my book Million Dollar Proposals (Wiley, 2012).