CHAPTER 2

My Money, Myself

Overheard in a conversation between two investors:

“You know, once people realize you are wealthy, they assume you know more than you actually do. Ha!”

Now that you have just been named CEO of this new company called My Wealth, Inc., let’s look at the reality of who is responsible for the management of this company. How on earth will you figure it out? Whom can you trust? What is the best way to run this company?

The “best” will differ for each person. Some newly appointed CEOs are more comfortable running the company in a hands‐on fashion; others prefer to elect VPs to do it for them. Many of us fall somewhere in the middle. You can structure your wealth however you want, but you can’t abdicate your role as CEO. So, know your options, uncover the conflicts of interest, and get involved in setting up the best team to run My Wealth, Inc.

But first, you have to learn about My Wealth, Inc. As you read this book, you will be engaged in taking stock, answering questions, and ranking priorities—all of which are designed to move you toward a heightened awareness of yourself as CEO of My Wealth, Inc. This will help you see what sort of investor you are—either a do‐it‐yourselfer or someone who prefers an advisor.

What is my wealth supposed to do?

Let’s start with the purpose of your wealth: security, freedom, legacy, or power. Vote for your top two choices. Trust your first response and don’t think too hard about it. You might think all four are relevant, but try to narrow it down to just two winners.

Understand the tension between your two winners. Accept that your views may change because your life changes, causing you to reconsider what wealth means to your life (e.g., when you sell your business or receive a large inheritance). Examine how a definition of your wealth’s purpose will impact whomever you choose as advisor. Why should you bother? Because the more your values align with the values of your chosen advisor, the greater the likelihood of compatibility and success.

Sometimes there is a hidden influence you need to openly acknowledge. For instance, if financial security is not one of your choices because, deep down, you believe you have enough money to feel secure, you might be unpleasantly surprised at the first market crash when your deepest fears surface—and you panic! Another hidden influence might be an expectation of an inheritance. Admitting that you expect a hefty inheritance in 10, 20, or 30 years helps you omit security as one of your winners because you don’t need to worry. Maybe that will happen, and maybe it won’t. Be alert to what you assume, and acknowledge that if you don’t inherit any additional money, your attitude may change quite a bit.

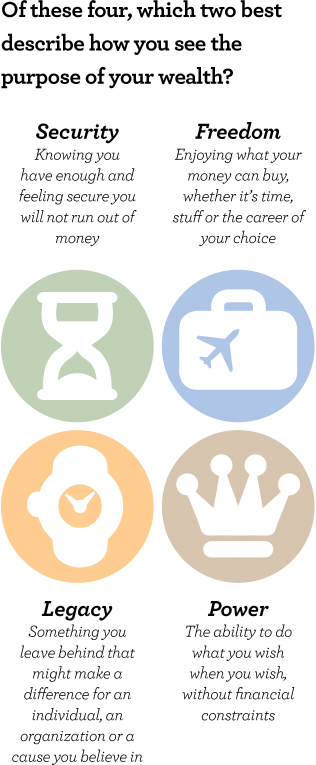

Now that you have this knowledge of your wealth’s purpose, the next step is to better define who you are as an investor. It may feel odd that we start with what irritates you in your current or past dealings with financial services. Why start there? Because your pet peeves will point out your true needs in a wealth management relationship.

What really bugs me . . .

Recall the very worst sales pitch you’ve ever heard. Or think about a meeting with your current advisor. What was the most irritating aspect of that meeting?

Here are annoyances cited by other investors. See which ones you identify with—or write your own.

By first addressing each of your pet peeves, you will see what those irritants tell you about what you require and expect from an advisor.

Let’s go through several examples of how you might fix each problem. Often it starts with a more candid conversation—and clearer communication from you.

How to fix jargon overload

My grown daughter taught me an expression I really love: “This isn’t working for me.” When she says this to me, I am unable to counter or argue. I have to stop and listen to her—and try another way of communicating. So when you’re overloaded with jargon, you could say:

- This isn’t working for me.

- I don’t like this use of jargon.

- Can you try that in English?

How to fix too much selling

You might have to interrupt the presentation. Saying “This isn’t working for me” can wake everyone up to your needs. Consider suitability, too. If what you value in an individual’s personality is a far cry from what this professional is demonstrating, you might need to admit this to both yourself and the presenter. Or you might try saying:

- You sound like you are selling something.

- I would prefer to hear about (e.g., your track record in 2008) rather than (e.g., your view on the economy).

- I need to tell you there is a disconnect here: You want to sell me, but I would prefer that you get to know me first. The product you are describing may or may not meet my goals.

How to fix a lack of authenticity

All the sales training in the world cannot fake authenticity1 or a true desire to serve you, the client. Keep your antenna tuned in to false notes—clichés like “We custom fit your portfolio so you can sleep at night.” Try saying:

- Because you probably don’t know yet what helps me sleep at night, tell me about risk—how you manage it and how you learn about my tolerance for it.

- First tell me what you know (not who you are or how old your firm is), and show me evidence of your skills. Then I can decide if I want to buy from you.

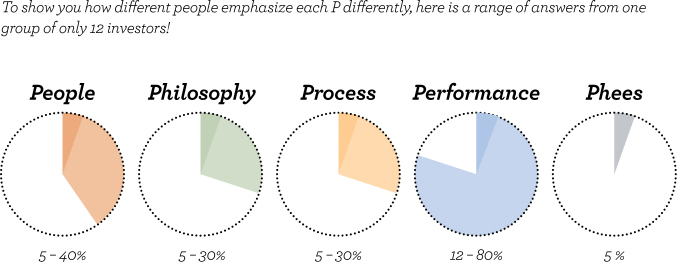

Where you’re most vulnerable: The five Ps exercise

What is most important to you about any financial services firm you might hire? Think of the firm as having five key components:

- Performance (How have they done?)

- Philosophy (What they believe about markets, investing, and interacting with clients)

- Process (How decisions are made within the firm)

- People (Who they are)

- Phees (What they charge)

Out of 100 percent, your task is to allocate how much weight you give to each component of any firm you are considering to entrust with your assets. There are no right answers. This is just your perception—your opinion of what’s most important.

Here is where individual differences emerge. This simple exercise will show you how you will hear what is said and how you will weigh what is shown to you.

Let me give you an example: If you allotted 50 percent to performance, you will be susceptible to a fantastic (maybe too fantastic) track record. If you assigned 75 percent to people, you may be swept off your feet by people who are just like you. These people speak your language, wear the same clothes as you, and may even share your eye color. The only trouble is, you may miss real problems with how this firm actually performs for its clients. In contrast, if fees figure prominently in your percentage allocation, you may decline to hire a firm whose fees are in fact quite fair for the services rendered—but seem too high to you.

The takeaway from this exercise is straightforward. Be wary if your percentages are not evenly distributed. If you have one P that dominates your assessment of any firm you consider, you may have a blind spot on that very P. By recognizing your bias or your preference among the five Ps, you have protection against missing something vital.

The bottom line is you need to know what you prefer, what you really expect, and what you require. Awareness of your biases and preferences will protect you from failing to catch something. Of course, you also need to remember that you are always in charge of what you actually receive in this relationship. Communication can remedy many of the most irritating situations, but remember—you are the one who needs to clearly communicate.

So far, you are unwrapping more about yourself than uncovering anything about an advisor. But do you even need an advisor? Maybe, maybe not. Let’s figure that out in the next chapter.