CHAPTER 7

Transparency, or How I Learned to Love Conflicts of Interest

An investor overheard warning a friend: “Airplane salespeople, car salesmen, and the investment industry are to be reviewed very carefully before you get in business with them. Caveat emptor!”

You’re making money on me?

In 2008, New York Times readers were shocked to read about medical tests being ordered by a physician for monetary reasons—the physician was paying off debt on the million‐dollar imaging machine in the office.1

In 2013, the Wall Street Journal reported a startling fact: The rate of spinal surgery at hospitals where surgeons own medical device distributorships is three times higher than at hospitals overall.2 Today, we can no longer assume that our physician is abiding by a code of ethics and earnestly wants to heal us. In 2013, pharmaceutical giant Glaxo announced that they would cease paying incentives to physicians who prescribed their drugs in order to keep “in step with the changing times.”3 Sadly and undeniably, financial incentives can and do influence the medical profession.4

Incentives matter on Wall Street, too

You may not know if an advisor has a financial incentive to sell you one product instead of another. Competing interests are by definition conflicts of interest. If you are sold a product because it has a payoff/fee commission for the advisor, you may not benefit at all—or you might miss out on another superior product because it paid out less to your advisor.

Be aware that it matters little to the unscrupulous advisor if the investment is not so appropriate for your situation. On the other hand, just because an advisor might receive an incentive to sell you an investment does not mean that the investment is inappropriate for you. In short, just because a conflict exists does not mean that you should not work with this advisor.

Not just for the criminally minded

Attractive incentives can tempt even the most dedicated professional—not just the scoundrels we see in headlines or movies.5 And few, if any, investors should be naive enough to believe that their advisor is not influenced by financial incentives.

If advisors can make more money in commissions or incentives by suggesting one fund over another, almost identical fund, why wouldn’t they recommend the one that makes them the most money?

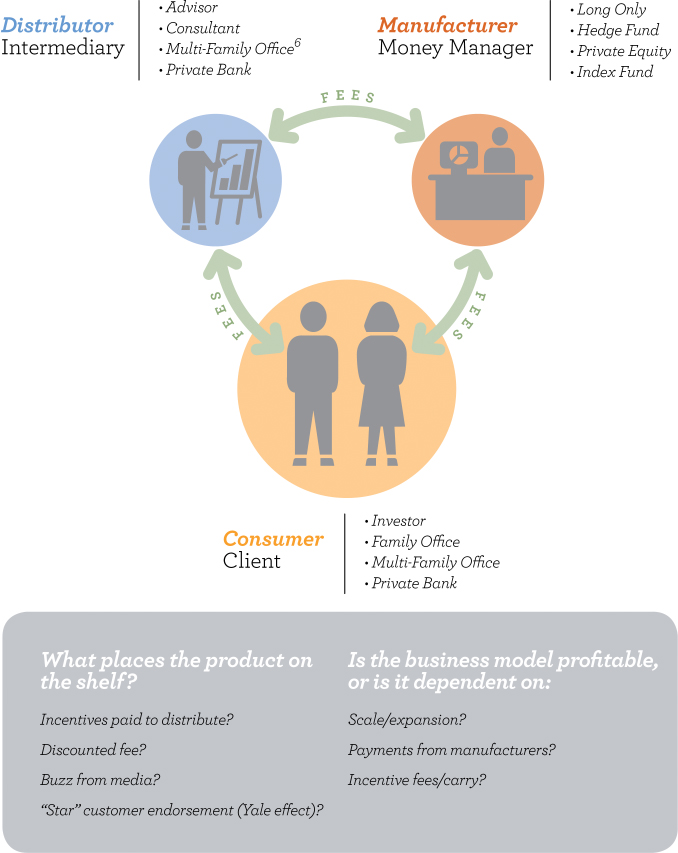

Here is the conflict: Because you might pay more when the other identical fund would have cost you less, your interests were made subordinate to your advisor’s. To fully grasp this concept, consider the world of a retail grocery operation. There is a manufacturer of the food and products, and the distributor may or may not pay for shelf space. The retail grocer may or may not accept payments to push certain products or place them prominently in the grocery store. The investment world works the same way, with a manufacturer, a distributor, and a consumer.

A long and colorful history of scandal has dogged Wall Street since its inception. Because there is so much money to be made, and it seems so easy to make it, many unsavory types are drawn to the industry. The late Leon Levy, a brilliant and beloved investment executive, explained why. He cited the true meritocracy and potential for huge monetary rewards on Wall Street as the reason why Wall Street attracts “the best, the brightest, and those who cheat.”7 In addition, because there is so much money to be made, many investors are drawn to the markets—searching for that quick payoff so often publicized in the news. As portrayed by the 24/7 business news, the public securities markets seem utterly enthralling and exciting. Is it any wonder that private investors fall for the pitch and ignore the conflicts of interest over and over again? Loss of money and subsequent regret prompts many investors to vehemently assert that they will accept only “conflict‐free advice.”

Conflict‐free advice = the Tooth Fairy

Let’s first define the term. Conflict‐free means that the advice I give you, the investment products I offer you, offer no increased benefit to me if you take my advice. Whether you take the advice or not, I do not win or lose. Therein lies the problem. If you hired me as your advisor because you believe I will always be right, I now have a vested interest in making sure you keep believing that. I may not readily admit I picked the wrong fund because you will be disappointed. You might lose faith in my judgment. So I delay telling you or maybe even keep information from you.8

One suggested cure for conflicts is disclosure. Pages of regulatory proscriptions are designed to address exactly how and when advisors should disclose conflicts to you. The fairytale ending is that you will thus be able to make an informed decision as to whether this conflict is one you can live with.

The only trouble is, Yale professor Daylian Cain showed that actually the exact opposite takes place.9 Cain’s real‐life research showed that once a conflict was disclosed, investors tended to make a decision that was not in their best interest—ignoring the conflict that actually hurt them. Said another way, you are more prone to relax your antennae of due diligence and do less investigation because the conflict was disclosed.

So why not just rely on a list of the “best” as compiled by a magazine or association? Why not select from the lists of the Top 100 Brokers or the 100 Best Financial Advisors that are published annually? Because there is a conflict of interest intrinsic in most published lists.10 You are unwittingly trusting that the list is not influenced by a revenue source, such as advertising or pay‐to‐play.

Open architecture can be drafty

Another purportedly conflict‐free solution is open architecture, where the advisor uses only outside funds or managers. Does this protect an investor? Hardly. Why not? Because the conflict of open architecture is more subtle and easy to miss. In open architecture, the advisor boasts that the firm uses none of its own “inside” products, only vetted “outside” funds or managers—and so is giving only objective, conflict‐free advice.

Twenty years ago I used the image of Home Depot to illustrate open architecture, where all products come from external sources. Way back in 1996, IPI members (and other investors) were seeking a trustworthy guide to navigate this warehouse. Two‐thirds of the IPI membership used advisors as guides or figuratively wandered through the aisles, having firms fill out long RFPs11—just like Yale, whose fantastic performance they admired and were trying to emulate. But even the open architecture movement became discredited, especially after product placement arrangements came to light.

Here was one investor’s assessment of open architecture:

I think open architecture is a buzzword that has been [adopted by advisors] over the last 5 or so years. I think it does not generate better, or worse, performance. I think it is independent of performance, and largely a marketing fig leaf. When the salespeople spend time touting “open architecture,” they are not talking about what they are actually going to do to help you. [I] have a lot of faith in [the] investment manager, not in open architecture.

Is this investor unfairly bashing open architecture? Where are the problems? There are two: First, the firm may be receiving an incentive fee to offer you that product or fund. Or the firm may pay an incentive for access to that fund and then pass along that fee to you, the client. One private bank’s clients were offered a famous firm’s hedge funds without being told that the private bank had paid an incentive fee for exclusive access, which they then deducted from each client’s portfolio.12 In other words, you are paying your portion of this incentive fee, and your returns will be less than those of the investors who purchased the funds directly from the firm. Wouldn’t you want to know about any and all such arrangements? Because the payment may not be disclosed to you, you may not ever know of this conflict. You may not be told of such payments even if you ask: “Are you paying or being paid to sell me this fund?” You may not be told of such payments.13 Asking for the answer to your question in writing usually inspires a more thoughtful answer.

Even if there is no payment being made to your advisor, your advisor must still defend the managers and advice they are giving you. The conflict is subtle; of course, they will stand behind their choice of outside managers/funds for you. They tell you they have done extensive due diligence. But here is the conflict: They may assume their continued relationship with you depends on being right 100 percent of the time, and as a result, advisors hesitate to admit when they are wrong. Waiting to fire one of the outside managers for even a year or two can damage your returns. But fear may prevent your advisor from taking action in a more timely manner.

Here is the simply stated conflict of interest as expressed to me by one advisor: “If I tell you the truth, I may lose you as a client. If I hide the truth, I may keep you as a client. I keep my fingers crossed, hoping the problem/mistake will go away so I’ll save face and my livelihood.”

Conflicts of interest—yours, mine, and ours

Advisors catering to the high‐net‐worth investor have kept one more dirty little secret under wraps for their own self‐preservation. This conflict is insurmountable. Serving as a fiduciary, that is, adhering to a professional standard of care, will conflict at every turn with running a profitable business. This conflict is constant—presenting competing priorities at every turn—and is impossible to eliminate. Just as the doctor I mentioned earlier buys expensive MRI machines and then recommends the procedure to patients, advisors might recommend investments to you because they get a payment to do so. This professional standard versus business profitability conflict can overwhelm even the most prudent professional. These advisors may not even realize they are making conflicted decisions, sincerely believing—or rationalizing—that their decision is being made for solid professional reasons and in your best interest.

When investors were less sophisticated, the wealth advisory business was far more profitable.14 Today it’s far more cutthroat and competitive. Standardization of service and a preset menu of investment choices is the path toward being profitable. Yet that is not appealing to an ultra‐wealthy investor, who wishes to be seen as unique and even treated as the most important client. No patient wants to feel like the doctor is rushing an examination because the waiting room has so many other patients.

The cost of your advisor staying in business, and how it impacts you

The cost of running a successful advisory business includes human resources, compliance, research, and technology. In response, a number of firms have transformed themselves into investment firms because offering pure advice or consulting is less profitable than selling investment products bundled into advice.15 Mounting costs also can mandate growing assets or curtailing time spent on client service by senior professionals. As a client of this firm, your demands can present very challenging conflicts of interest.

Your demands might be unrealistic, even naive:

- Why shouldn’t I receive favored fees over less wealthy, retail investors? Aren’t I more valuable to your firm, especially if I let you use my name as a reference?

- Why can’t you produce that report for me? I don’t care that it’s not standard, or that it requires hours of manual input into your systems.

- Why can’t you spend hours explaining what trades you are doing? I deserve the attention of your chief investment officer, because I have more assets with your firm than other clients. Since I pay based on assets under management, don’t I deserve to get more of your time?

There is no silver‐bullet solution or even a straightforward way to address these less obvious conflicts of interest. If your every demand is met, the firm’s profitability could evaporate, and the firm could go out of business. That will benefit neither of you. If you and your advisor are truly candid with each other, however, you acknowledge that fulfilling the professional standards of a profession often presents a conflict with the requirements of a profitable business.

First, accept that immutable fact. Then discuss exactly how you two will try to balance the self‐interest on both sides. These are important steps to take toward a healthier partnership between you and your advisor.