18

PRINCIPAL FEDERAL AND STATE TAX REPORTING AND REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS

- The Importance of Meeting Federal and State Reporting Requirements

- Organizations Exempt from Tax

- Charitable Organizations

- Private Foundations

- Private Operating Foundations

- Other Concerns for Charities

- Noncharitable Exempt Organizations

- Unrelated Business Income

- Registration and Reporting

- Reports by Recipients of Federal Support

- Principal Federal Tax Forms Filed

- Conclusion

- State Compliance Requirements

THE IMPORTANCE OF MEETING FEDERAL AND STATE REPORTING REQUIREMENTS

Congress has imposed an income tax on all individuals and organizations with few exceptions. Those organizations that are exempt from such tax are known as exempt organizations. Generally, not-for-profit organizations are exempt organizations if they meet certain specific criteria as to the purpose for which they were formed and whether their source of income is related to that purpose. But even an exempt organization can be subject to tax on certain portions of its income and, if the organization is a private foundation, it is subject to a number of very specific rules as well as certain excise taxes. In addition, most larger tax-exempt organizations, other than churches, are required to file annual information returns with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Certain organizations must also register and file information returns with certain of the state governments even though they are not residents in the state.

Finally, the not-for-profit organization must pay withheld payroll taxes to the government. If not, the IRS can and will hold board members and managers personally liable for unpaid payroll taxes, regardless of a declaration of bankruptcy or the corporate form of organization. In addition, not-for-profit organizations must be aware of the various compliance requirements relating to employee benefit plans that may be offered to their employees.

NOTE: Under the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, not-for-profit entity employers had to treat qualified transportation fringe benefits, such as parking and transit passes, as unrelated business income beginning January 1, 2018. This has resulted in many more not-for-profit entities being required to file the Form 990T and pay unrelated business income tax. This requirement was removed by Congress in early 2020. Refunds of any amounts paid can be obtained.

The first part of this chapter discusses two aspects of not-for-profit organizations' relations with the federal government: (1) qualification for tax-exempt status under the Internal Revenue Code, and (2) reporting requirements applicable to organizations that receive support in the form of federal grants, contracts, loans, loan guarantees, and similar awards. Examples of annual information returns are provided. The second part of this chapter focuses on state reporting requirements.

This discussion is intended only to give the reader a general understanding of the tax rules and is not intended to be a complete discussion of the law and the tax regulations. It is provided to assist financial statement preparers and their auditors to determine whether a provision for income taxes should be made in the financial statements, either because an organization is not exempt or because an organization earns income that is subject to tax. Each organization should consult with its own tax accountant or attorney about its status and any specific problems it may have. For financial statements to be presented fairly in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles, the tax status of the not-for-profit organization must be determined, otherwise the determination of whether an income tax provision is needed cannot be made. Furthermore, even a tax-exempt organization may conduct activities that are subject to income tax. The tax rules must be understood to record any required tax provision appropriately.

Intermediate Sanctions

In 1996, Congress passed a bill generally referred to as the “Intermediate Sanctions” legislation. This law gives the IRS power to assess penalties against exempt organizations and their managers, short of revocation of exempt status, for various violations of the Internal Revenue Code. Previously, the only effective sanction available to the IRS was revocation of exempt status, which the Service was understandably reluctant to impose except in cases of very serious violations. Lesser violations often went unpunished for lack of an appropriate level of punishment.

The provisions of the law apply to organizations exempt under Sections 501(c)(3) (not including private foundations) and 501(c)(4) and include penalties that may be assessed against both the management of the organization and the individual responsible for an improper transaction. Types of transactions covered by the law are generally those in which some kind or amount of benefit is given to a person not properly entitled to it.

Another provision of the law requires organizations to provide a copy of their Form 990 to persons requesting it. A reasonable charge may be made for copying. Penalties are incurred for failure to file a Form 990 or to make it available on request.

In 1997, Congress passed many changes in the tax law, generally referred to as the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997. There are many, but mostly minor, matters affecting not-for-profit organizations in the new law. Most of the changes have to do with split-interest gifts, unrelated business income, estate and gift taxes, and deductions for charitable contributions.

On August 17, 2006, the Pension Protection Act of 2006 became law. This new law has several provisions that affect tax reporting and compliance by not-for-profit organizations, some of which are as follows:

- Controlling organizations must report income from and loans to controlled organizations, as well as transfers between controlled and controlling organizations on their Form 990 information returns due after the date of the enactment of the new law.

- Section 501(c)(3) organizations must now disclose unrelated business income tax returns (Form 990-T) and make them available for public inspection. This provision is effective for returns filed after the date of the enactment.

- Private foundation and excess benefit penalty excise taxes are doubled.

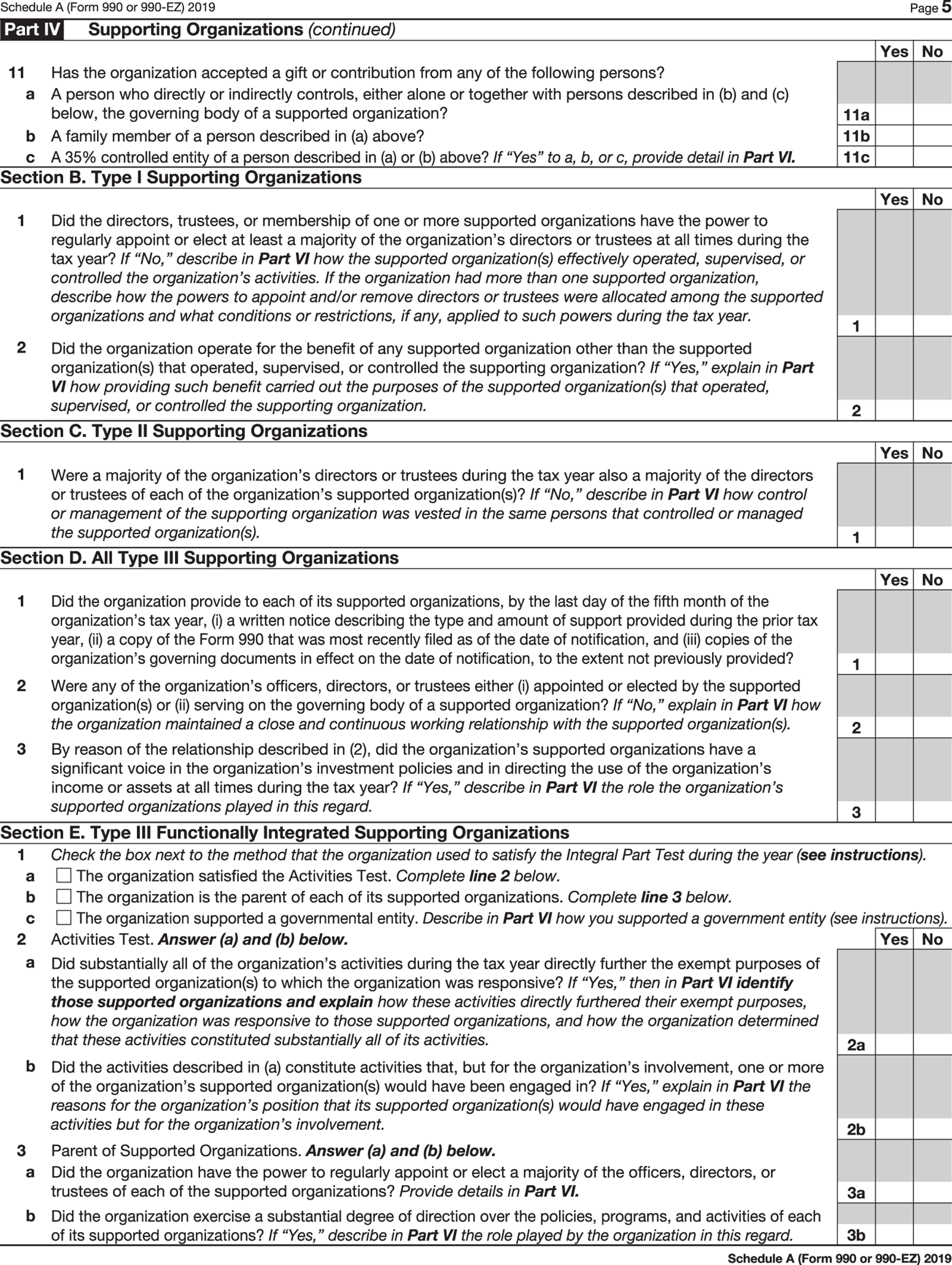

- Donor advised funds, supporting organizations, and credit counseling organizations are subject to new requirements.

- Charitable contribution deductions for food, book, and certain conversation property are increased.

- Charitable contribution deductions for nonmonetary donations, certain easements, taxidermy property, clothing and household goods, and certain other items are limited.

- Exempt organizations (other than private foundations) with gross receipts under $50,000 must file an annual notice called an “e-Postcard” (Form 990-N).

Not-for-profit organizations should review the new requirements to assess their impact on each organization's tax compliance and reporting matters.

Private Inurement

One of the essential requirements for many organizations seeking exemption is that they must be organized and operated in such a way that no part of their net earnings inures to the benefit of any private shareholder or individual. The phrase “no part” means the level of inurement is not material; any inurement at all, no matter how small, could endanger an organization's tax-exempt status.

Private inurement is prohibited for many organizations. The term encompasses transactions that confer preferential treatment upon private shareholders or individuals. The concept requires investigation of the transactions between the organization and its insiders (i.e., those who can control the use of the organization's assets). Section 501(c)(3) allows exemption for an organization only if no part of the net earnings of the organization inures to the benefit of any private shareholder or individual. A private shareholder or individual is a person or persons having a personal and private interest in the activities of the organization.

Organizations can lose their exempt status due to private inurement from unreasonable compensation or fringe benefits, personal use of an organization's assets, forgiveness of indebtedness owed by insiders, personal expenses being paid by the organization, low-interest or unsecured loans to insiders, unreasonable housing allowances, and other than arm's-length purchases or sales between the organization and insiders.

To avoid the private inurement issue, organizations should avoid transactions with insiders that even remotely appear to unreasonably benefit the insider. This does not prohibit an organization from transacting business with members of its board of directors or paying competitive salaries. It does mean that certain guidelines need to be applied, and all transactions should be properly documented before relationships with insiders are formed.

ORGANIZATIONS EXEMPT FROM TAX

The Internal Revenue Code (IRC) provides exemption from tax for certain organizations that meet very specific requirements. The most widely applicable of these exemptions are:

- Corporations, and any community chest, fund, or foundation, organized and operated exclusively for religious, charitable, scientific, testing for public safety, literary, or educational purposes, or to foster national or international amateur sports competition … or for the prevention of cruelty to children or animals, no part of the net earnings of which inures to the benefit of any private shareholder or individual, no substantial part of the activities of which is carrying on propaganda, or otherwise attempting to influence legislation1 [except as otherwise provided in subsection (h)], and which does not participate in, or intervene in (including the publishing or distributing of statements), any political campaign on behalf of any candidate for public office (Sec. 501[c][3]).2

- Clubs organized for pleasure, recreation, and other nonprofitable purposes, substantially all of the activities of which are for such purposes and no part of the net earnings of which inures to the benefit of any private shareholder (Sec. 501[c][7]).

- Business leagues, chambers of commerce, … not organized for profit and no part of the net earnings of which inures to the benefit of any private shareholder or individual (Sec. 501[c][6]).

- Corporations organized for the exclusive purpose of holding title to property, collecting income therefrom, and turning over the entire amount thereof, less expenses, to an organization which itself is exempt … (Sec. 501[c][2]).

There are other categories of exempt organizations found in the IRC under Sections 501, 521, 526, 527, and 528, but the exemptions listed above cover the majority of not-for-profit organizations. This chapter focuses on the exemption requirements for charities and discusses three other examples of exempt organizations: social clubs, trade associations, and title-holding companies. Other categories of exempt organizations are not discussed here.

CHARITABLE ORGANIZATIONS

Most exempt organizations are categorized as charitable organizations or Sec. 501(c)(3) organizations. There are four main purposes that organizations exempt under Sec. 501(c)(3) may have: religious, charitable, scientific, or educational. This covers organizations such as churches, hospitals, schools, community funds, museums, medical research organizations, and social service organizations.

All Sec. 501(c)(3) organizations must be “organized and operated exclusively for” one of these purposes. In order to meet the “organizational test,” an organization's charter must limit its purpose to one or more of the exempt purposes allowed and must not expressly empower the organization to engage, other than as an insubstantial part of its activities, in activities that are not in furtherance of the organization's exempt purpose(s). An organization's charter must also contain certain language and restrictions to conform to the requirements for a Sec. 501(c)(3) organization. Organizations that contemplate application for recognition of exempt status under Sec. 501(c)(3) should consult with qualified legal and tax counsel to ensure that the organizing documents meet the requirements of the organizational test.

An organization that meets the organizational test must actually operate within the boundaries established by its charter in order to meet the “operational” test. The operational test requires that organizations engage primarily in activities that further one or more exempt purposes. Also, in order to pass the operational test, organizations must serve a public, rather than private, interest, must not attempt to influence legislation as more than an insubstantial portion of activities, and must not benefit a private shareholder or individual.

The Tax Reform Act of 1969 created two general categories of Sec. 501(c)(3) organizations. Each category is subject to different rules. The two categories are private foundations and public charities, also referred to as publicly supported organizations. All Sec. 501(c)(3) organizations are assumed to be private foundations unless they meet a statutory public support test or are considered not to be private foundations under a specific statutory definition.

- Publicly supported organizations receive broad public support. An individual donor may normally deduct contributions to such organizations in amounts up to 50% of the donor's adjusted gross income.

- Private foundations are organizations that do not receive broad public support but instead receive most of their support from a limited number of donors or from investment income. Private foundations are subject to many restrictions on their activities and are subject to certain excise taxes. Normally an individual donor may deduct contributions to private foundations in amounts only up to 30% of the donor's adjusted gross income.

A publicly supported organization is defined for this discussion3 as a “Sec. 501(c)(3) organization that is not a private foundation.”4 There are three principal categories of organizations that are not private foundations. These three categories are as follows:

- Organizations formed exclusively for religious, charitable, scientific, literary, or educational purposes, or to foster national or international amateur sports that normally receive a substantial portion of their support from direct or indirect contributions from the general public or from a governmental unit. Also excluded from private foundation status are churches, educational institutions with a faculty and student body, hospitals, and medical research organizations related to a hospital. [Sec. 509(a)(1)]

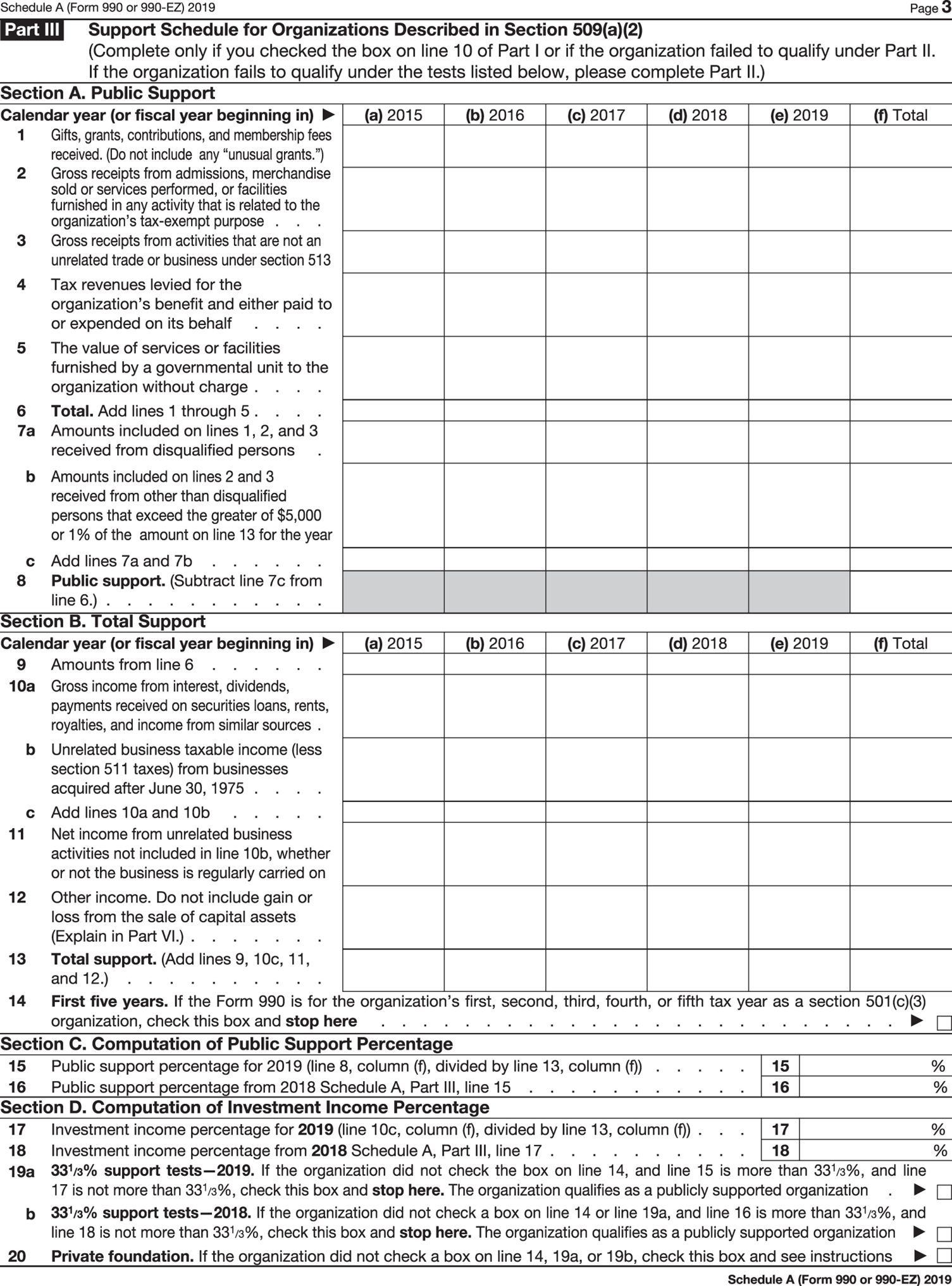

- Organizations that meet both of the following mechanical tests, based on actual support during the previous four years: [Sec. 509(a)(2)]

- The organization receives not more than one-third of its support from gross investment income; and

- The organization receives more than one-third of its support from a combination of:

- Contributions, gifts, grants, and membership fees, except when such income is received from disqualified persons;5 and

- Gross receipts from admissions, sale of merchandise, performance of services, or furnishing facilities, all of which must be derived from an activity related to the organization's exempt purpose. Excluded from gross receipts are any amounts from any one person, governmental unit, or company in excess of $5,000 or 1% of total support (whichever is greater) and amounts received from disqualified persons.

- Organizations organized and operated exclusively for the benefit of, to perform the functions of, or to carry out the purpose of a publicly supported charity, or to perform a charitable purpose in support of a Sec. 501(c)(4), Sec. 501(c)(5), and/or a Sec. 501(c)(6) organization (Sec. 509[a][3]). These organizations are called “supporting organizations.” They are not required to meet either public support test as long as the organization that is supported meets one of the support tests discussed above. When the supported organization is a Sec. 501(c)(4), Sec. 501(c)(5), or Sec. 501(c)(6) organization, the supported organization must meet the support test under Sec. 509(a)(2), a test to which the supported organization would not normally be subject.

The law and regulations provide mathematical tests for public support. The tests are very technical and are different depending on whether the organization must meet the test under 1 or 2 above. A detailed discussion of the two different public support tests is beyond the scope of this book.

Simply stated, the test under Sec. 509(a)(1) requires that one-third of an organization's support come from the general public. The test under Sec. 509(a)(2) requires that one-third of an organization's support come from the general public and not more than one-third of an organization's support come from gross investment income. Support is calculated over an aggregated four-year period and the calculations are performed on the cash basis.

Excluded from the calculation under each test are unusual grants. Unusual grants are defined in the regulations under Sec. 509. A grant must meet the following requirements before it may be excluded from the public support calculation as an unusual grant:

- The grant was a substantial contribution from a disinterested party.

- The grant was attracted by reason of the publicly supported nature of the organization.

- The grant was unusual or unexpected in respect to the amount.

- The grant would, by reason of its size, adversely affect the organization's public support test.

This provision enables organizations to receive infrequent large amounts from generous donors without losing public support status.

Organizations exempt under Sec. 501(c)(3) must file Schedule A of Form 990. Schedule A includes a schedule for organizations to complete regarding the support they received for the four years prior to the current taxable year. The Internal Revenue Service performs additional mathematical calculations on the information provided in the schedule to confirm that the organization has met the public support test to which it is subject.

This discussion shows generally how these rules are applied. There are a number of exceptions to these rules and each organization should consult with legal or tax counsel to determine exactly how these rules affect it. Also, keep in mind that this mechanical test is applied only to organizations with at least four years' experience. Younger organizations having at least one year's experience can obtain a “temporary” exemption until they have four years' experience, at which time the above tests are applied.

PRIVATE FOUNDATIONS

Private foundations are charitable organizations that are subject to specific rules and taxes that do not apply to publicly supported organizations. The most important provisions that apply to private foundations are:

- Payment of an excise tax on investment income;

- Distribution of at least a minimum amount of income (as defined);

- Disposition of excess business holdings;

- Avoidance of certain prohibited transactions;

- Filing a complex annual information return.

Excise Tax on Investment Income

The Tax Reform Act of 1969 established an excise tax on net investment income:6 Net investment income includes dividends, interest, rents, royalties, and net capital gains.7 For purposes of calculating gain on investments acquired prior to December 31, 1969, the tax basis of the property is the higher of the fair market value at December 31, 1969, or the cost. In calculating net investment income, reasonable expenses directly related to the production of investment income can be deducted. Also, income that is subject to unrelated business income tax is not included in the calculation of net investment income. This would include items of income such as interest or dividends from debt-financed stocks and bonds and capital gains from the sale of debt-financed assets. An example of the excise tax applied to a private foundation that had stocks and bonds that were acquired both before and after December 31, 1969, follows:8

| Taxable income | ||

| Dividends and interest | $10,000 | |

| Sale of stock A for $45,000 purchased in 1967, at a cost of $20,000, but having a market value at December 31, 1969, of $30,000 | ||

|

$45,000 | |

|

(30,000) | |

| Gain | 15,000 | |

| Sale of stock B for $20,000 purchased in 1968 at a cost of $15,000, but having a market value at December 31, 1969, of $25,000 | ||

|

$20,000 | |

|

(25,000) | |

| Difference, not recognized for tax purposes. No loss is recognized if using the December 31, 1969, market value creates a loss | $(5,000) | |

| Sale of stock C for $15,000 purchased in 1970 at a cost of $20,000 | ||

|

$15,000 | |

|

(20,000) | |

|

(5,000) | |

|

20,000 | |

| Less investment advisory fees and other expenses | (2,000) | |

|

$18,000 | |

| Tax at 2% | $ 360 |

It is important to keep accurate accounting records of the cost basis for all investments as well as an accurate segregation of any expenses applicable to investment income. With respect to investments acquired prior to December 31, 1969, it is also important to keep a record of the fair market value as of December 31, 1969.

Foundations are required to pay estimated excise taxes on a quarterly basis.

Tax Consequences of Gifts of Securities

On investments received by gift subsequent to December 31, 1969, the contributor's tax basis is the basis that the foundation must use when calculating taxable gain. For investments received prior to December 31, 1969, the basis is the higher of fair market value at December 31, 1969, or contributor's tax basis. In most instances, the fair market value is higher. Thus, a private foundation must obtain from the donor, at the time a gift of securities is received, a statement of tax basis. This is very important and great care should be taken to obtain this information promptly upon receipt of the gift. At a later date the donor may be difficult to locate or may have lost the necessary tax records. Since donated securities are recorded for accounting purposes at fair market value at date of receipt, the foundation must keep supplementary memo records of the donor's tax basis.

Here is an illustration of how two gifts of the same marketable security can have different tax consequences to the private foundation. Both gifts made in 1980 involve 100 shares of stock A.

Gift 1—Very low basis:

Mr. Jones acquired his 100 shares of stock A in 1933 when the company was founded. His cost was only 10 cents a share, and therefore his basis for these 100 shares was only $10. Market value on the date of gift was $90 a share, or a total of $9,000. The tax basis to Mr. Jones of $10 carries over to the private foundation. If the foundation later sells the stock for $10,000, it will pay a 2% tax on $9,990 ($10,000 sales proceeds less $10 tax basis), or a tax of $199.80.

Gift 2—Very high basis:

Mr. Smith acquired his 100 shares of stock A in 1970 at a cost of $110 a share or a total of $11,000. The market value on the date of his gift was also $90 a share, or a total of $9,000. If the private foundation later sells this stock for $10,000, it will have neither a taxable gain nor loss. In this instance, the donor's basis of $110 a share carries over to the foundation for purposes of calculating taxable gain, but for purposes of calculating loss, the fair market value at date of gift ($90 a share) becomes the tax basis. Since the sales price ($100) is more than the fair market value at the date of gift ($90), but less than the donor's cost ($110), there is no gain or loss recognized.

As can be seen from this example, in one instance the private foundation had to pay a tax of $199.80 and in the other instance had no tax. Rather than sell appreciated stock and pay excise tax on the gain, a foundation might consider distributing the stock to a publicly supported organization and letting the distributee organization sell it. The distributee organization would not incur tax on the gain since capital gains are exempt from unrelated business taxable income and publicly supported organizations are not subject to the excise tax on net investment income. To the extent a private foundation has capital losses, they can be offset against capital gains in the same year. If there are no capital gains to offset such losses, the losses cannot be offset against investment income. Capital losses cannot be carried over to another year.

Distribution of Income

A private foundation is required to make qualifying distributions of at least the distributable amount by the end of the year following the current taxable year. Qualifying distributions are those amounts paid to accomplish the exempt purposes of the foundation. If the foundation fails to distribute the required amount, it may be subject to taxes that ultimately have the effect of taxing 100% of any amount not distributed.

Starting in 1982, the “distributable amount” is defined as the minimum investment return, less the excise tax and, where applicable, less the unrelated business income tax.

The minimum investment return is 5% of the fair market value of all the foundation's assets that are not used in directly carrying out the organization's exempt purpose. Cash equal to 1.5% of the total foundation's assets is deemed to be used in carrying out the exempt purpose and is deducted for this calculation. This means that if a foundation has marketable securities and cash with a market value of $1,000,000, it must make minimum qualifying distributions of 5% of $985,000 ($1,000,000 less 1.5% of $1,000,000) or $49,250, regardless of its actual income. If, for example, actual investment income were only $30,000, the foundation would still have to make qualifying distributions of $49,250.

Note that contributions and gifts received are included in the calculation of the distributable amount only to the extent that they increase the fair market value of the foundation's assets.

This means that the private foundation will not have to make qualifying distributions out of principal, provided its investment income plus contributions and gifts equal the distributable amount. In the preceding example, if contributions to the foundation were $50,000, the distributable amount would still be $49,250. These requirements will have little effect on private foundations that receive continuing contribution support.

Here is an illustration showing how these calculations work. Using the condensed financial statements of the A. C. Williams Foundation, the distributable amount is calculated as follows:9

| A. C. Williams Foundation Summary of Receipts and Expenditures | ||

| Receipts: | ||

|

$140,000 | |

|

50,000 | $ 190,000 |

| Expenditures: | ||

|

70,000 | |

|

1,000 | 71,000 |

|

$ 119,000 | |

| Assets | ||

| Cash | $ 30,000 | |

| Marketable securities | 970,000 | |

| Net assets | $1,000,000 | |

| Calculation of Distributable Amount | ||

| Investment income | $ 50,000 | |

| Minimum investment return: | $ 50,000 | |

| Average fair market value of securities and cash9 | ||

| Less 1.5% of above amount for cash deemed to be used in carrying out the exempt purpose | (15,000) | |

|

985,000 | |

|

5% | |

| $ 49,250 | ||

| Distributable amount: | $ 49,250 | |

|

(1,000) | |

|

$ 48,250 | |

Thus, the distributable amount is $48,250. Qualifying distributions were $70,000, which exceeds the distributable amount by $21,750, and the requirement has thus been met. This excess can be carried over for five years to meet the requirements of a year in which there is a deficiency. Where there is such a carryover, the order of application of the amounts distributed would be current year, carryover from earliest year, carryover from next earliest year, and so forth.

Excess Business Holdings

A private foundation is not allowed to own a stock interest in a corporation if the stock it owns together with the stock owned by disqualified persons10 would exceed 20% of the voting stock. The provision also applies to holdings in partnerships, joint ventures, and beneficial interests in trusts.

Prohibited Transactions

There are several categories of transactions in which private foundations may not engage. They cannot engage in “self-dealing,” make investments that jeopardize their exempt function, or make expenditures for certain prohibited purposes (so-called taxable expenditures). There is an excise tax both on the foundation and on the foundation manager who engages in these prohibited transactions. For example, the tax on taxable expenditures is initially 10% and 2.5% on the foundation and foundation manager, respectively, but is increased to 100% and 50%, respectively, if corrective action is not taken within a specified period of time.

Self-dealing. The law prohibits private foundations from engaging in certain transactions with disqualified persons, or foundation managers. These prohibited self-dealing transactions include the sale, leasing, or lending of property or money, the furnishing of goods or services on a basis more favorable than that granted to the general public, or the payment of unreasonable compensation. Disqualified persons may continue to support the foundation by lending money without charge and providing goods and services for charitable use without charge. The prohibition against self-dealing prevents disqualified persons from receiving a benefit from their relationship with a foundation but does not generally prevent the foundation from receiving a benefit from the disqualified person.

All transactions involving a disqualified person should be examined very closely to make absolutely certain they do not involve self-dealing.

Investments that jeopardize exempt function. The law provides that the foundation may not make investments that jeopardize the exempt function of the foundation. The foundation is expected to use a “prudent trustee's approach” in making investments. Examples of investments that probably would not be prudent would be investments that have a high level of risk.

Prohibited expenditures. The law provides that a foundation may not make expenditures to carry on propaganda to influence legislation or the outcome of a public election. It also prohibits making a grant to an individual for travel or study without prior Internal Revenue Service approval of the grant program. The law also provides no grant shall be made to another private foundation or to any noncharitable organization unless the granting foundation exercises expenditure control over the grant to see that it is used solely for the purposes granted. Finally, the law prohibits a private foundation from making any grant for any purpose other than a charitable purpose.

Annual Information Return

The annual information return (Form 990-PF) filed with the Internal Revenue Service is considerably longer and more complex than Form 990 filed by most other not-for-profit organizations. A discussion of the annual return and an illustration of the completed form are included later in this chapter.

A private foundation must also furnish a copy of the annual return to anyone desiring to see it.

PRIVATE OPERATING FOUNDATIONS

Private operating foundations are private foundations that actively conduct charitable program activities that are the exempt function for which the organization was founded. This is in contrast to private foundations that act only as conduits for funds and have no operating programs as such. Private operating foundations have most of the characteristics of publicly supported organizations but do not meet the public support tests outlined for such organizations that were discussed earlier in this chapter.

Qualifying Tests

In addition to expending substantially all (85%) of its income directly for the active conduct of its exempt function, a private foundation, to be a private “operating” foundation, must meet one or more of the following tests:

- It devotes 65% or more of the fair market value of its assets to direct use in its exempt function.

- Two-thirds of its minimum investment return is devoted to its exempt function and used chiefly by the foundation to accomplish that function.

- It derives 85% or more of its support, other than investment income, from the general public and from five or more exempt organizations, none of which provides more than 25%. In addition, not more than 50% of its total support is from investment income.

Advantages

There are several advantages to being a private operating foundation. The minimum distribution rules imposed on private foundations do not apply to private operating foundations and donors are allowed to deduct a contribution to a private operating foundation up to 50% of the donors' adjusted gross income versus the 30% of donors' adjusted gross income limitation on contributions to private foundations.

OTHER CONCERNS FOR CHARITIES

Contribution Disclosures

Contributions other than cash are subject to special reporting by both donors and recipient charities. Contributors must attach Form 8283 to their tax returns to support noncash charitable contributions of $500 or more to the same donee. The form requires an appraisal by a competent, independent appraiser and, in some cases, the recipient organization is required to sign the form also. If the recipient organization is required to sign the form, and disposes of the property within two years of the date of the gift, then the organization must file Form 8282 with the Internal Revenue Service within 125 days of the disposition. The organization must also supply the donor with a copy of Form 8282. By requiring this reporting, the Internal Revenue Service is better able to monitor sizable charitable deductions on individual returns.

Contribution Acknowledgments

For single charitable contributions of property and/or cash of $250 or more, donors will need an acknowledgment from the charity to substantiate a charitable tax deduction. A canceled check is not sufficient in this case. Charities should be prepared to acknowledge gifts to assist their individual and corporate donors with substantiation of these deductions. A recent change in tax law now requires donors to obtain written evidence substantiating all charitable contributions for which a tax deduction is taken. A canceled check is sufficient for gifts under $250.

Solicitation Disclosures

When an organization gives a donor something in return for a contribution, for example, a dinner or a raffle ticket, the amount given may not constitute a charitable contribution. A portion, or all, of the payment may be payment for receipt of a benefit, and not a gift to the organization. Revenue Ruling 67-246 and Revenue Procedure 90-12 provide guidance to organizations that provide a benefit to donors in conjunction with solicitation of funds.

Organizations must inform their donors, in clearly stated language, how much, if any, of the payment is deductible as a charitable contribution if the total received is greater than $75. An example of this is an organization that sponsors a fundraising dinner. A comparable dinner in a restaurant would cost a donor $50. In order to attend the dinner, donors pay $200. In this case, the organization must inform donors that $150 of their $200 payment is deductible as a charitable contribution. Charities should print this information on the donors' tickets or receipts, thereby providing donors with documentation for the charitable deductions they claim on their tax returns.

There are exceptions for low-cost items that are distributed as part of a fundraising effort. Charitable organizations should consult the Revenue Ruling and Revenue Procedure and ensure that their solicitation materials comply. The Internal Revenue Service is empowered to impose penalties in cases of failure to comply with the notification requirements.

Excise Tax Considerations

There are several excise taxes imposed on organizations under certain circumstances. The following provides a short summary of each tax:

- Excess Expenditures to Influence Legislation—Sec. 4911 imposes a 25% excise tax on the excess lobbying expenditures (including grassroots lobbying expenditures) of an organization that has elected to be covered under Sec. 501(h). The election under Sec. 501(h) provides qualifying organizations with a safe harbor for their lobbying and grass- roots expenditures. In any year in which the organization's lobbying expenses exceed the safe harbor amounts, the organization must pay the excise tax under Sec. 4911.

- Tax on Disqualifying Lobbying Expenditures of Certain Organizations—If an organization loses its status under Sec. 501(c)(3) because of making more than an insubstantial amount of lobbying expenditures, Sec. 4912 imposes excise taxes on an organization and its management. The tax on the organization is 5% of the lobbying expenditures in the taxable year in which Sec. 501(c)(3) status is revoked. A separate 5% excise tax is imposed on the management of the organization, if the management agreed to the expenditures while knowing the organization might lose its exemption. This excise tax does not apply to private foundations or organizations that elect the safe harbor of Sec. 501(h). (Note that organizations that lose their Sec. 501(c)(3) status when more than an insubstantial portion of their activities is lobbying may not become exempt under Sec. 501[c][4].)

- Political Expenditures of Sec. 501(c)(3) Organizations—Sec. 501(c)(3) organizations are forbidden from participating or intervening in any political campaign on behalf of or in opposition to any candidate for public office. Sec. 4955 imposes a two-level excise tax on the organization and its management that participate in prohibited activities. The first level of tax is imposed on the organization at the rate of 10% of the amount of the expenditures, and on the management at the rate of 2.5% of the expenditures if the management agreed willfully to the expenditures. If the organization does not correct the political expenditure by obtaining a refund of the amounts spent, a second level tax of 100% and 50% of the expenditure is imposed on the organization and management, respectively. (Note that if a private foundation makes political expenditures and pays the tax imposed by this section, then the expenditures will not also be taxed under Sec. 4945 as taxable expenditures.)

Summary of Individual Tax Deductions

Charitable organizations depend, to a very large extent, on individual contributions for support. To the extent that a contributor receives a tax deduction for a contribution, there is more inclination to be generous in the contribution. Accordingly, the tax deductibility of a contribution is of real importance. Exhibit 1 summarizes the general rules applicable to common types of contributions.

As Exhibit 1 indicates, the amount of deduction allowed in any year is limited to a percentage of the donor's adjusted gross income. Contributions limited in this manner may be carried forward for five years until fully used. The adjusted gross income limitation depends on the type of donee organization, the type of property donated, and whether the organization will use the property in pursuit of its exempt purpose (related) or will use the property in a way unrelated to its exempt purpose (such as selling the property).

Gifts of appreciated property may have additional tax implications to the donor. Because the charitable contribution rules are somewhat complex, donors should consult with their tax advisors before making a large contribution to any organization. Exhibit 1 is intended to be a general guide only.

| Charitable Contribution Table | ||||

| Factors | ||||

| Type of property | Type of organization | Use by organization | Amount of deduction | AGI limitation |

| Cash | Public | Any | Actual amount | 50% |

| Private | Any | Actual amount | 30% | |

| Long-Term Capital Gain (LTCG): | ||||

|

Public | Any | FMVa | 30% |

| Private | Any | FMV less LTCGb | 20% | |

|

Public | Related | FMVa | 30% |

| Unrelated | FMV less LTCG | 50% | ||

| Private | Related | FMV less LTCG | 20% | |

| Unrelated | FMV less LTCG | 20% | ||

|

Public | Any | FMV less OI | 50% |

| Private | Any | FMV less OI | 30% | |

|

Public | Any | FMV | 50% |

| Private | Any | FMV | 30% | |

Key AGI—adjusted gross income

FMV—fair market value

Public—50% type charities including private operating foundations

Private—30% type charities including private nonoperating foundations

a Taxpayer may elect to decrease the amount of deduction to fair market value less long-term gain potential and to increase the AGI limitation to 50%.

b In the case of a contribution of qualified appreciated stock to a private nonoperating foundation, the full FMV is deductible.

NONCHARITABLE EXEMPT ORGANIZATIONS

Social and Recreation Clubs

Another type of organization that is granted exemption from tax is the club “organized for pleasure, recreation, and other nonprofitable purposes, substantially all of the activities of which are for such purposes and no part of the net earnings of which inures to the benefit of any private shareholder.” Social and recreation clubs are exempt as long as substantially all their activities are for members. Income derived from nonmember activities, such as investment income and nonmember use of the club, can have significant implications for the social club.

Exempt status. Significant use of the club by nonmembers can result in loss of the club's tax exemption. The congressional committee reports of the Tax Reform Act of 1976 indicate that a social club will retain its exempt status if no more than 35% of its gross receipts are from investments and nonmember use of facilities. Within this 35%, no more than 15% can be derived from nonmember use of facilities.

Gross receipts include receipts from normal and usual activities of the club, including charges, admissions, membership fees, dues, assessments, investment income, and normal recurring gains on investments, but exclude initiation fees and capital contributions.

Gross receipts from nonmembers are amounts derived from nonmember sources such as investment income and amounts paid by members involving non–bona–fide guests. Amounts paid by a member's employer can, depending on the situation, be considered as paid by a member or as paid by a nonmember.

The problem of determining whether someone using the club is a bona fide guest of a member has proven troublesome. Most clubs adopt rules that limit use of the facilities to members and their guests. The Internal Revenue Service has taken the position that, in many situations, the member's participation in, or connection with, a function is so limited that the member is merely using the membership to make the club facilities available to an outside group. In many instances, the member is viewed merely as acting as a sponsor.

If a member's charges are reimbursed by an employer, the income will be member income if the event is for a personal or social purpose of the member, or due to a direct business objective of the employer. If there is no direct relationship between the business objective or purpose of the activities, the reimbursement will be considered nonmember income. The distinction is where the member has a direct interest in the company function as contrasted with a situation where the member is merely serving as a sponsor to permit the company to use the facilities.

There are also guidelines to help determine whether group functions hosted by members at which guests are present constitute member or nonmember receipts. In groups of eight or fewer individuals, it is assumed that all nonmembers are guests. In larger groups, it is assumed that all nonmembers are bona fide guests, provided 75% of the group are members. In all other situations the club must substantiate that the nonmember was a bona fide guest. In the absence of adequate substantiation it will be assumed such receipts are nonmember receipts, even though paid for by the members.

Substantiation requirements. In order to rely upon the above assumptions regarding group functions, clubs must maintain certain records. Where the “8 or fewer” rule or the “75% member rule” is used, it is necessary to document only the total number in the party, the number of members in the party, and the source of the payments. For all other group occasions involving club use by nonmembers, even where a member pays for the use, the club must maintain records containing the following information if it wishes to substantiate that such receipts are not “nonmember” receipts:

- Date;

- Total number in the party;

- Number of nonmembers in the party;

- Total charges;

- Charges attributable to nonmembers;

- Charges paid by nonmembers.

In addition, the club must obtain a statement signed by the member indicating whether the member will be reimbursed for such nonmember use and, if so, the amount of the reimbursement. Where the member will be reimbursed, or where the member's employer makes direct payment to the club for the charges, the club must also obtain a statement signed by the member indicating (1) the name of the employer, (2) the amount of the payment attributable to the nonmember use, (3) the nonmember's name and business or other relationship to the member (or, if readily identifiable, the class of individuals, e.g., sales managers), and (4) business, personal, or other purpose of the member served by the nonmember use.

Recordkeeping requirements for other activities such as providing guest rooms, parking facilities, steam rooms, and so on, have not been specifically set forth. Clubs must be careful to ensure that their recordkeeping procedures provide information regarding member and nonmember use of these facilities. All social clubs must be extremely careful not to receive, even inadvertently, nonmember income in excess of allowable limits.

Unrelated business income. In addition to jeopardizing its exempt status, receipts from nonmembers have other tax implications for a social club since such receipts constitute unrelated business income. Social clubs are subject to tax at regular corporate tax rates on their unrelated business income. This is calculated on a somewhat different basis than for other types of exempt organizations. The total income of the club from all sources except for exempt function income (dues, fees, etc., paid by the members) is subject to tax. This means that income from nonmembers, as well as investment and other types of income, is subject to tax. Deductions are allowed for expenses directly connected with such income, including a reasonable allocation of overhead. As with other exempt organizations, there is a specific deduction of $1,000 allowed.

It is possible for a social club to have an overall loss but still have a substantial amount of unrelated business income. Here is an example of a country club where this is the case.

| Exempt | Unrelated | Total | |

| Interest on taxable bonds | -- | $10,000 | $ 10,000 |

| Membership fees | $ 100,000 | -- | 100,000 |

| Golf and other fees | 40,000 | 20,000 | 60,000 |

| Restaurant and bar | 200,000 | 50,000 | 250,000 |

| Total income | 340,000 | 80,000 | 420,000 |

| Direct expenses | (320,000) | (30,000) | (350,000) |

| Overhead | (60,000) | (20,000) | (80,000) |

| Net income (loss) | $(40,000) | $30,000 | $(10,000) |

This club will have taxes to pay on $30,000 of income, which at the 15% corporate tax rates is $4,350.11

One of the real burdens for social clubs is to keep their bookkeeping records in such a manner that it is possible not only to determine direct expenses associated with nonmember income, but also to provide a reasonable basis of expense allocation between member and nonmember activities. Even the largest of corporations has difficulty in making allocation of overhead between functions, so the problems of allocation for social clubs should not be passed over lightly.

Many social clubs charge nonmembers enough to cover the direct costs of the services provided but consistently incur overall losses on nonmember income when they allocate overhead and indirect expenses to nonmember income. This loss enables a club to offset investment income and other unrelated business income when calculating the tax it must pay. The Internal Revenue Service has taken the position that an activity that consistently generates losses does not have the requisite profit motive needed for a trade or business. Under this position, the Service contends that the activity is not an unrelated trade or business and the losses from the activity may not be used to offset other types of unrelated income. In Portland Golf Club v. Commissioner, 90-1 USTC paragraph 50.332, the Supreme Court agreed with the Service's position. Social clubs should reevaluate their cost allocations and the amounts they charge nonmembers and should consider whether the activity is pursued with a motive for profit.

Trade Associations

Another example of an exempt noncharitable organization is a trade association exempt under Sec. 501(c)(6). Trade associations are membership organizations that function for the common business purpose of their members. The activities of a trade association must be directed toward the improvement of business conditions as opposed to performing particular services for individual persons or members.

Contributions or dues paid to a trade association are not deductible as charitable contributions. Most members, however, are entitled to deduct dues and other fees paid as a business deduction.

Lobbying expenses. Expenses paid after December 31, 1993, for lobbying activities, that is, activities engaged with the intent to influence legislation, are not deductible for tax purposes. The nondeductibility of lobbying expenses is extended to the portion of business dues paid to trade associations allocable to the trade association's lobbying activities. Trade associations must either notify members as to the portion of member dues that are not deductible, or pay a “proxy tax” equal to the highest corporate income tax rate on amounts expended for lobbying purposes. The provisions governing member notification and payment of the “proxy tax” are complex, and trade associations should consult with their professional advisors on this issue.

Unrelated business income. Trade associations are taxed on net unrelated business income the same way that charitable organizations are taxed. Interest, dividends, rents, and royalties are exempt as long as the property that generates the income is not debt financed. Membership dues and meeting and convention receipts are also not income from an unrelated trade or business.

Title-Holding Companies

Sec. 501(c)(2) provides an exemption for corporations that hold title to property, collect the income therefrom, and remit the net income to another exempt organization annually. These organizations most frequently hold title to real property but may also hold investment portfolios. The organizations are allowed exempt status because of their relationship to the parent exempt organization. Possible abuse situations are avoided by requiring the Sec. 501(c)(2) organization to remit net income from the property to the exempt parent and forbidding a Sec. 501(c)(2) organization from participating in any activity except holding title.

Unrelated business income. Because Sec. 501(c)(2) organizations are forbidden from any activity other than holding property, the only source of unrelated business income they might have is income from debt-financed property under Sec. 514. Unrelated business income is discussed in more detail in the next section.

UNRELATED BUSINESS INCOME

Virtually every exempt organization, including churches and clubs, is subject to normal corporate taxes on its unrelated business income. In order for financial statements of not-for-profit organizations to be prepared in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles, provisions for tax liability on unrelated business income must be considered.

Under the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, not-for-profit entity employers had to treat qualified transportation fringe benefits, such as parking and transit passes, as unrelated business income beginning January 1, 2018. This has resulted in many more not-for-profit entities being required to file the Form 990T and pay unrelated business income tax. This requirement was removed by Congress in early 2020. Refunds of any amounts paid can be obtained.

Definition

There is always difficulty in knowing exactly what is unrelated business income. Here is the way the law reads:

The term “unrelated trade or business” means … any trade or business the conduct of which is not substantially related … to the exercise or performance by such organization of its charitable, educational, or other purpose or function constituting the basis for its exemption … [Sec. 513(a) of the Internal Revenue Code] … the term “unrelated business income” means the gross income derived by any organization from any unrelated trade or business … regularly carried on by it, less the deductions … which are directly connected … [Sec. 512(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code].

There are three key phrases in these definitions. The first is “unrelated,” the second is “trade or business,” and the third is “regularly carried on.” All three criteria must be present for an activity to be categorized as an unrelated trade or business activity. It is not difficult to determine whether the business in question is “regularly carried on,” but it is difficult to know what is truly unrelated, and it is sometimes difficult to ascertain what is a trade or business. The burden is on the exempt organization to justify exclusion of any income from this tax.

According to Regulation Sec. 1.513-1(d), unrelated business income results within the meaning of Sec. 513(a) if the conduct of the trade or business that produces the income is not substantially related (other than through the production of funds) to the purposes for which exemption is granted. The presence of this requirement requires organizations to distinguish between the business activities that generate the particular income in question (the activities, that is, of producing or distributing the goods or performing the services involved) and the accomplishment of the organization's exempt purposes. In determining whether activities contribute importantly to the accomplishment of an exempt purpose, the size and extent of the activities involved must be considered in relation to the nature and extent of the exempt function, which they purport to serve.

The terms “trade” or “business” have the same meaning as in §162, and generally include any activity carried on for the production of income from the sale of goods or performance of services. In general, any activity of an otherwise exempt organization carried on in a commercial fashion that is similar to a trade or business and which, in addition, is not substantially related to the performance of the organization's exempt function is sufficiently close to the concept of a trade or business to be taxable.

The term does not include any trade or business:

- In which substantially all the work is performed for the organization without compensation;

- Which is carried on by the organization primarily for the convenience of its members, students, patients, etc.;

- Which is the selling of merchandise, substantially all of which has been donated as gifts or contributions to the organization.

According to the regulations under §1.513-1(b), the primary objective of adopting the unrelated business income tax rules was to eliminate a source of unfair competition by placing an unrelated business activity on the same basis with its for-profit counterparts. On the other hand, where an activity does not possess the characteristics of a trade or business within the meaning of §162, such as when an organization sends out low-cost articles incidental to the solicitation of charitable contributions, the unrelated business income tax does not apply because the organization is not in competition with taxable organizations.

According to Regulation §1.513-1(c), the regularly carried-on requirement must be applied in light of the purpose of the unrelated business income tax to place exempt organization business activities upon the same tax basis as the nonexempt business endeavors with which they compete. Hence, for example, specific business activities of an exempt organization will ordinarily be deemed to be regularly carried on if they manifest a frequency and continuity, and are pursued in a manner generally similar to comparable commercial activities of nonexempt organizations. Keep in mind that this requirement has to be applied in light of the purpose of the unrelated business income tax to place a trade or business on the same tax basis as the business endeavors with which it competes.

Many not-for-profit organizations have begun to invest in alternative investments, which is a term generally meant to include hedge funds, private equity funds, etc. For tax purposes, the not-for-profit organization may receive Form K-1s from these investments, on which their share of income is reported. As the K-1s often report types of income that would be subject to the unrelated business income tax, for example, ordinary income, the tax consequences (as well as foreign tax and foreign bank account reporting requirements) must be carefully evaluated and monitored. In some cases, a “blocker corporation” may hold these investments for the not-for-profit organization and effectively convert ordinary taxable income into investment income, which would be exempt. The point is that the tax aspects of these types of investments may be substantial and should be evaluated from a financial statement perspective to ensure any required tax provision is recorded.

Exclusions. There are a few exemptions from this tax. They include, among others, income from research activities in a hospital, college, or university, income from a business in which substantially all the people working for the business do so without compensation, and income from the sale of merchandise donated to the organization. There are special rules for social clubs, which were discussed previously, and other special types of exempt organizations not discussed here.

Also excluded from unrelated business income is passive investment income such as dividends, interest, royalties, rents from real property, and gains on sale of property. However, rents that are based on a percentage of the net income of the property are considered unrelated. Also, income (passive investment income and rent) from assets acquired by incurring debt (debt-financed property) and rent from personal property may be considered unrelated business income in whole or in part. Private foundations must still pay the excise tax on these items of passive income.

Advertising income. One example of a widespread activity that is generally considered an unrelated business activity is advertising. Many exempt organizations publish magazines that contain advertising. While this advertising helps to pay the cost of the publication, advertising is nevertheless considered to be unrelated business income. The advertising is not directly part of the organization's exempt function, and therefore is taxable. The fact that the activity helps pay for exempt functions is not enough. To be tax-free, it must be part of the exempt function. This is the distinction that must be made. The IRS has adopted tough rules with respect to the taxability of advertising income. The rules are complex and professional advice should be sought concerning their application.

Trade shows. The Tax Reform Act of 1976 provided an exclusion from unrelated business income for certain organizations, such as business leagues, that hold conventions or trade shows as a regular part of their exempt activities. In order for the exclusion to apply, the convention or trade show must stimulate interest in, and demand for, an industry's product in general. The show must promote that purpose through the character of the exhibits and the extent of the industry products displayed.

Caveats. The organization is allowed to deduct the costs normally associated with the unrelated business. This places a burden on the organization to keep its records in a manner that will support its business deductions. Overhead can be applied to most unrelated activities, but the organization must be able to justify both the method of allocation and the reasonableness of the resulting amount. Also keep in mind that if, after all expenses and allocation of overhead, the organization ends up with a loss, it will have to be able to convincingly explain why it engages in an activity that loses money. Logically, no one goes into business to lose money, and if there is a loss, the allocation of expenses to the taxable activity is immediately suspect.

Tax Rates on Unrelated Business Income

Unrelated business income is taxed at the same rates as net income for corporations. All exempt organizations having gross income from unrelated business activities of $1,000 or more are required to file Form 990-T within four and a half months of the end of the fiscal year (May 15 for calendar-year organizations). Extensions can be obtained if applied for before the due date of the return. Organizations are required to pay estimated taxes on a quarterly basis.

Need for Competent Tax Advice

From the above discussion, it should be obvious that taxes on unrelated business income may be substantial and can apply to most organizations. It must be emphasized that every organization contemplating an income-producing activity should consult with a competent tax advisor to determine the potential tax implications of that activity.

Uncertainty in Income Tax Provisions

GAAP has certain accounting and disclosure requirements related to uncertain tax positions, which can be found in the FASB ASC at 740-1. While primarily aimed at for-profit organizations that prepare tax accruals within their financial statements, these requirements are applicable to not-for-profit organizations, including those reporting tax provisions on unrelated business income.

The underlying concept of these requirements is that some tax positions taken by an organization may ultimately not prove acceptable to the taxing authority, resulting in a liability to that authority. FASB ASC 740-01 provides guidance in determining whether a risk threshold has been exceeded, and if it has, how to measure the resulting liability from the uncertainty.

A tax position is defined as “a position in a previously filed tax return or a position expected to be taken in a future tax return that is reflected in measuring current or deferred income tax assets and liabilities for interim and annual periods.” This definition includes, but is not limited to, the following:

- A decision not to file a tax return;

- An allocation or shift of income between two jurisdictions;

- The characterization of income or a decision to exclude reporting taxable income in a tax return;

- A decision to classify a transaction, entity, or other position in a tax return as tax exempt.

Note that exempt status itself is considered a tax position, and even though an organization may have a letter from the IRS attesting to that status, this letter was issued sometime in the past, and organizations must be able to show that they have not done anything since then to jeopardize that exempt status.

An organization should recognize the financial statement effects of a tax position when it is more likely than not, based on its technical merits, that the position will be sustained upon examination. More likely than not means a likelihood of more than 50%, considering the facts, circumstances, and information available at the reporting date.

Once a tax position meets the more likely than not recognition threshold, it is initially and subsequently measured as the largest amount of tax benefit that is greater than 50% likely of being realized upon ultimate settlement with a taxing authority that has full knowledge of all relevant information.

Not-for-profit organizations should consider the effects of applying the guidance of FASB ASC 740-01 to events or circumstances that could endanger their tax-exempt status and the potential impact on their financial statements, as well as considering its effect on tax provisions on unrelated business income and, for private foundations, the excise tax on net investment income. Chapter 23 describes specific considerations that not-for-profit organizations should make in evaluating their tax positions.

REGISTRATION AND REPORTING

Initial Registration

All charitable (Sec. 501[c][3]) organizations, except churches and certain charitable organizations having annual gross receipts of less than $5,000, must comply with Internal Revenue Service notification requirements before they may be considered exempt from income tax. Charitable organizations comply with these notification requirements by submitting Form 1023 to the Internal Revenue Service District Director within fifteen months of the start of their operations. If the application is approved, the Internal Revenue Service will send the organization a determination letter that recognizes the organization's exempt status and publicly supported (or private foundation) status under one of the law's provisions.

Organizations must file the application within fifteen months of the start of business in order to have exempt status apply to the organization's entire period of existence. Organizations that apply after the fifteen-month period expires will have exempt status recognized only from the date of the application.

Organizations that anticipate they will meet one of the public support tests are given an advance determination letter. This letter allows the organization up to sixty months to meet the public support test without being classified as a private foundation. If, at the end of the sixty months, or advance determination period, the organization fails to meet the support test, it will be characterized as a private foundation retroactive to the date operations began.

Exempt organizations other than Sec. 501(c)(3) charities may apply for recognition of exempt status by submitting Form 1024. Some noncharitable organizations are required to apply for recognition of exempt status (e.g., Voluntary Employee Benefit Associations) (Sec. 501[c][9]).

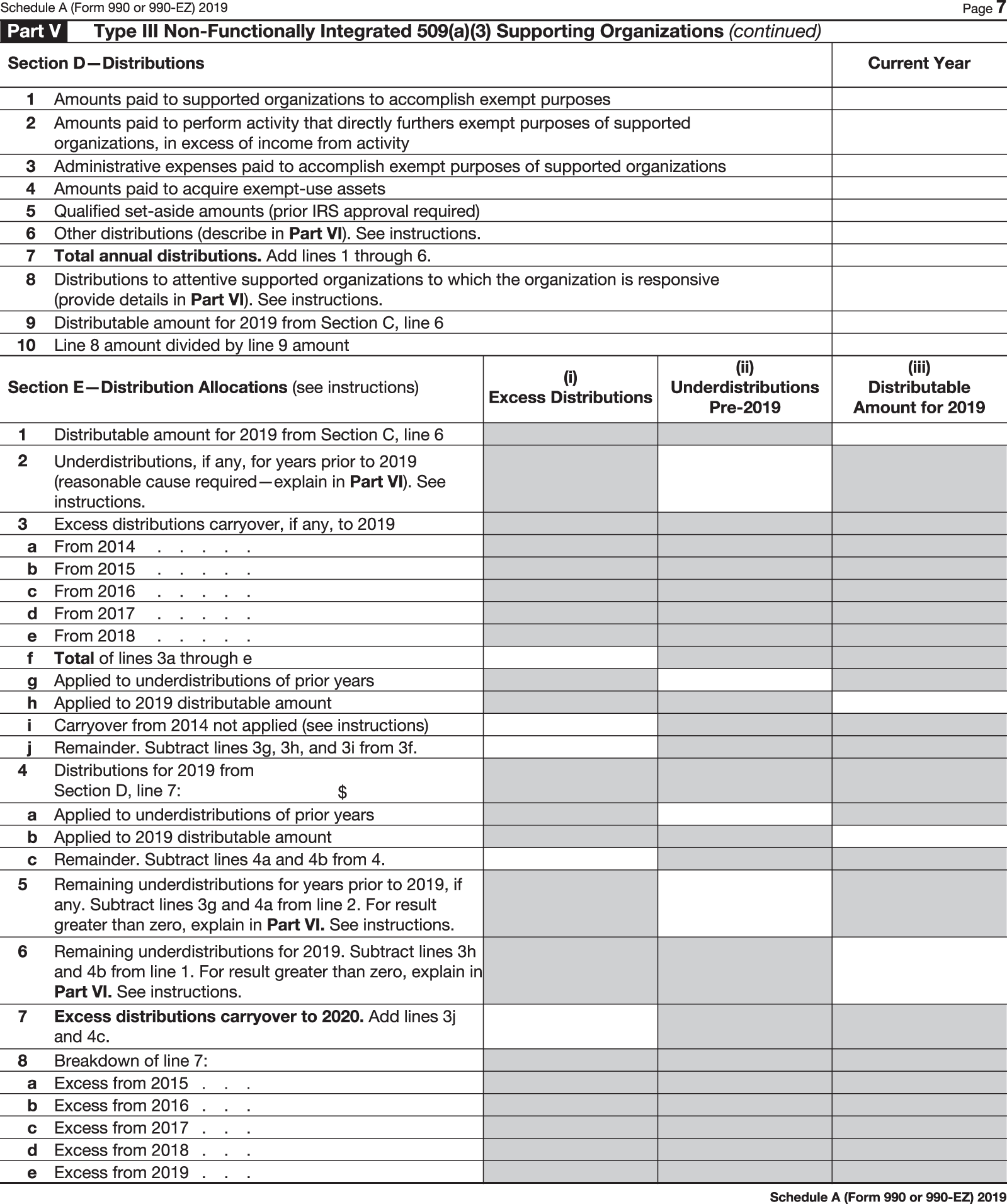

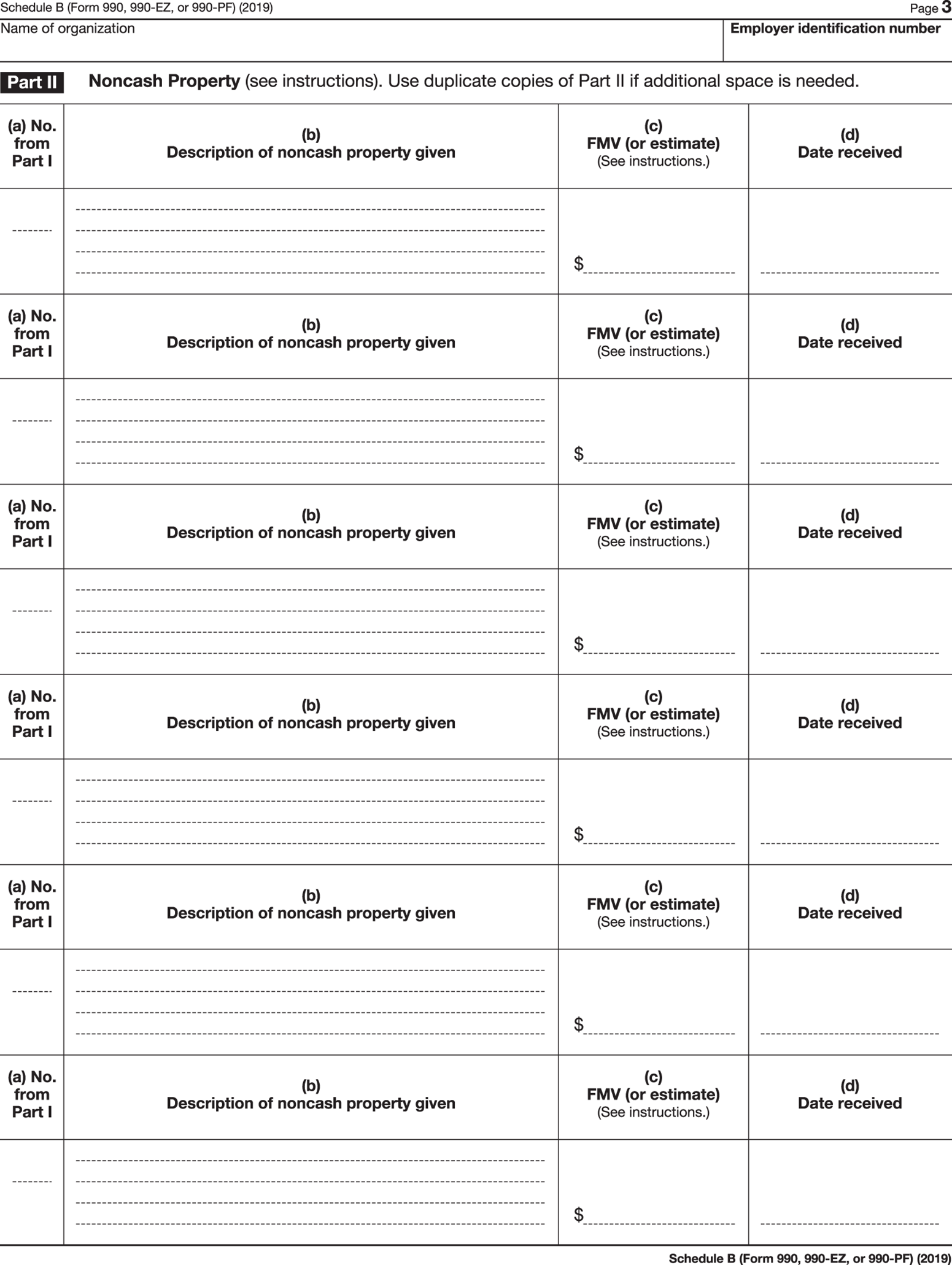

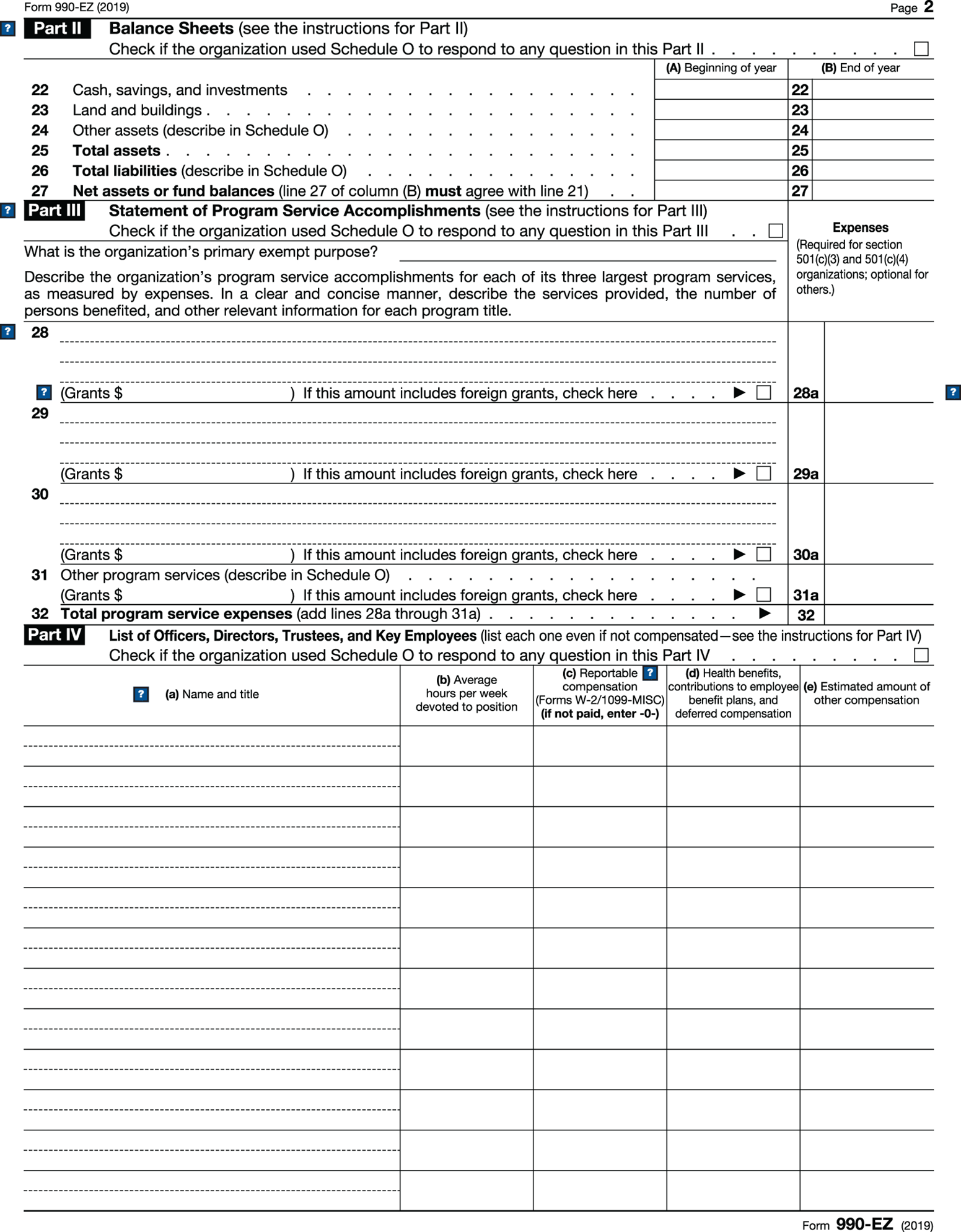

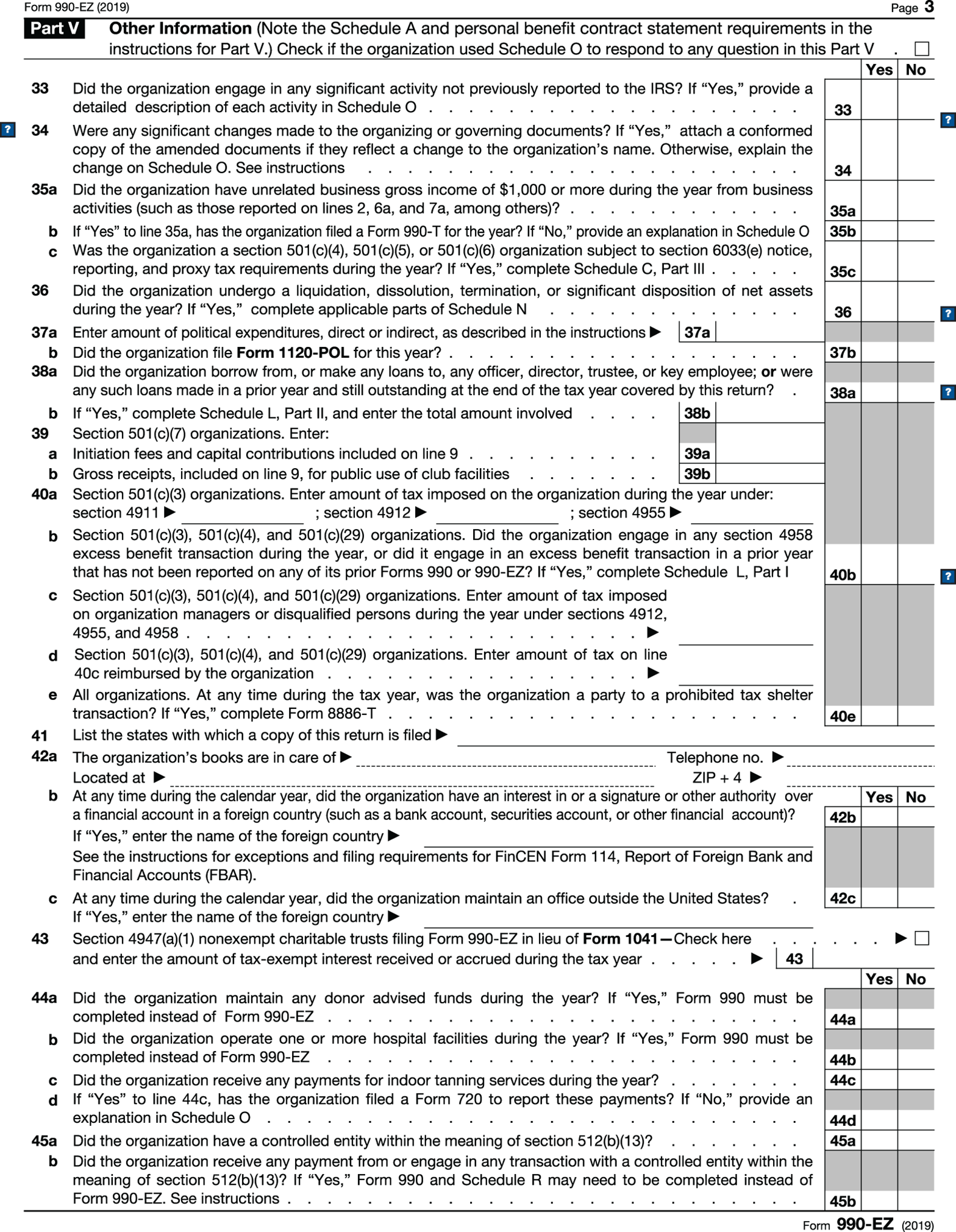

Annual Information Returns

Almost all exempt organizations are required to file annual information returns. The principal exceptions to this reporting requirement are churches and their integrated auxiliaries, and certain organizations normally having gross receipts of $50,000 or less. Most organizations must file Form 990, Return of Organization Exempt from Tax. For 2011, organizations with gross receipts of less than $200,000 for the taxable year and total assets at year-end of less than $500,000 may file Form 990-EZ. For Forms 990 and 990-EZ, a separate schedule (Schedule B) must be filed to provide information about contributors. Schedule B is generally not subject to public inspection. A sample of Schedule B is included in Exhibit 4. All private foundations must file Form 990-PF without exception.

These information returns must be filed by the fifteenth day of the fifth month after the end of the fiscal year (May 15 for calendar-year organizations). There is a penalty for failure to file the return on time. Extensions of time for filing can usually be obtained if there is good reason why the return cannot be filed on a timely basis, but application for extension must be made before the filing deadline. These returns do not require certification by an outside auditor.

In addition, all exempt organizations having gross unrelated business income of $1,000 or more must file a separate tax return and pay taxes at regular corporate rates on all taxable income over $1,000.

Return Inspection

All organizations exempt from tax under Sec. 501(a) or (d) must make their Form 990 (or 990-PF), and Form 990-T, if applicable, available for public inspection. Except for the list of contributors that are reported on the return on Schedule B, the return and all statements filed therewith must be made available for inspection upon request. Generally, a copy of the return must also be provided upon request. The Internal Revenue Service makes the annual return, except for lists of contributors, available to the general public. The Internal Revenue Service also makes an organization's Application for Recognition of Exempt Status (Form 1023 or 1024) available for public inspection. The regulations under Sec. 6104 provide procedures for requesting these forms from the Internal Revenue Service.

REPORTS BY RECIPIENTS OF FEDERAL SUPPORT

Not-for-profit organizations that receive support from the federal government usually must comply with various audit and reporting requirements. These apply whether the support is received directly from a federal agency or indirectly through a state or local governmental unit or another not-for-profit organization. Many different kinds of federal support can trigger these requirements; these kinds of support include grants, contracts, loans, loan guarantees, in-kind gifts (such as agricultural commodities), interest subsidies, and other forms of support.

It is beyond the scope of this book to present a detailed description of all of the audit and reporting requirements applicable to federal support, as they are numerous and complex. Organizations that receive or are considering applying for such support should take into consideration the time and costs associated with federally required audits, for they can be significant to those organizations. Readers should consult with a CPA or other knowledgeable person about these requirements. Failure to fulfill the requirements can result in severe financial penalties to the organization, including loss of future funding or even being compelled to repay amounts already received.

PRINCIPAL FEDERAL TAX FORMS FILED

While not-for-profit organizations may be exempt from most federal taxes, they must file annual information returns with the Internal Revenue Service. With few exceptions, all exempt organizations other than private foundations are required to file Form 990 or, if they qualify, Form 990-EZ annually. Private foundations are required to file Form 990-PF. Most not-for-profit organizations having “unrelated business” income must also file Form 990-T. Organizations that anticipate incurring a tax liability must pay estimated taxes in quarterly installments. This chapter discusses the principal returns and provides some general comments on some of the less obvious points that the preparer must be aware of while completing these forms. It is not meant to be a complete discussion of these tax matters, nor is it a comprehensive tax guide. Rather, it provides an introduction to the federal tax and reporting requirements to which a not-for-profit organization is subject.

Forms 990, 990-EZ, and 990-PF are all available for electronic filing. The IRS requires certain tax-exempt organizations to file annual exempt organization returns electronically. The regulations require organizations with total assets of $100 million or more to file electronically. However, the regulations only apply to entities that file at least 250 returns, including income tax, excise tax, employment tax, and information returns, during a calendar year. The IRS demonstrates this requirement by the following example.

Assuming the $100 million in assets criterion is met, if an organization has 245 employees, it must file its Form 990 or Form 990-PF electronically because each Form W-2 and quarterly Form 941 is considered a separate return. Therefore, the example organization files a total of 250 returns—245 W-2s, four 941s (which are quarterly), and one Form 990 or Form 990-PF.

Private foundations and charitable trusts are required to file Form 990-PF electronically regardless of their asset size, if they file at least 250 returns.

Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax

Who must file? All not-for-profit organizations exempt from income tax must file Form 990 except the following:

- Churches and certain other religious organizations.

- Organizations that are part of a federal, state, or local governmental unit.

- Most employee benefit plans (they file other forms).

- Organizations other than private foundations with annual gross receipts of $50,000 or less are required to electronically submit Form 990-N unless they choose to file a complete Form 990 or Form 990-EZ instead. Form 990-EZ can be filed by organizations with gross receipts of less than $200,000 and total assets of less than $500,000 at the end of the tax year.

- Private foundations (they file Form 990-PF).

Gross receipts means the total income recognized during the year, including contributions, investment income, proceeds from the sale of investments, and sale of goods, before the deduction of any expenses or costs, including the cost of investments or goods sold.

This means that most not-for-profit organizations including social clubs, educational institutions, and membership organizations must file a return. The return is due not later than the fifteenth day of the fifth month after the end of the fiscal year (May 15 for calendar-year organizations), and there is a penalty for failure to file unless it can be shown that there was a reasonable cause for not doing so. Continued failure to file can also result in personal penalties imposed on responsible persons associated with the organization.

Contents of Form 990. Beginning for the calendar year ended December 31, 2008, not-for-profit organizations must begin to use the version of Form 990 that has been significantly revised by the Internal Revenue Service. There are many additional requests for information on the new form, and not-for-profit organizations have found that the first year completing the new form can be very challenging. Many of the new information requests center around the not-for-profit organization's governance, adherence to its mission statement, and exempt function and compensation matters.

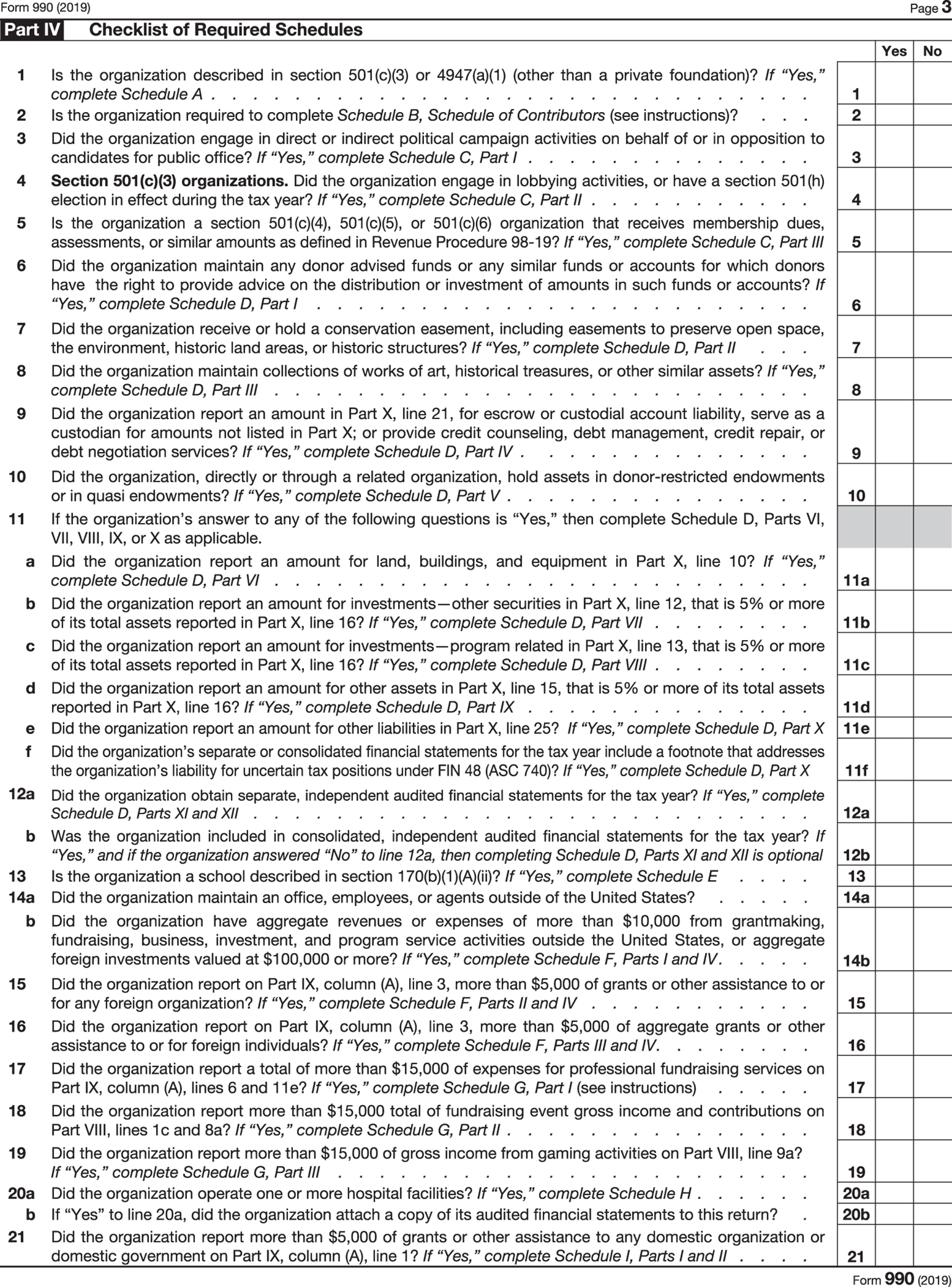

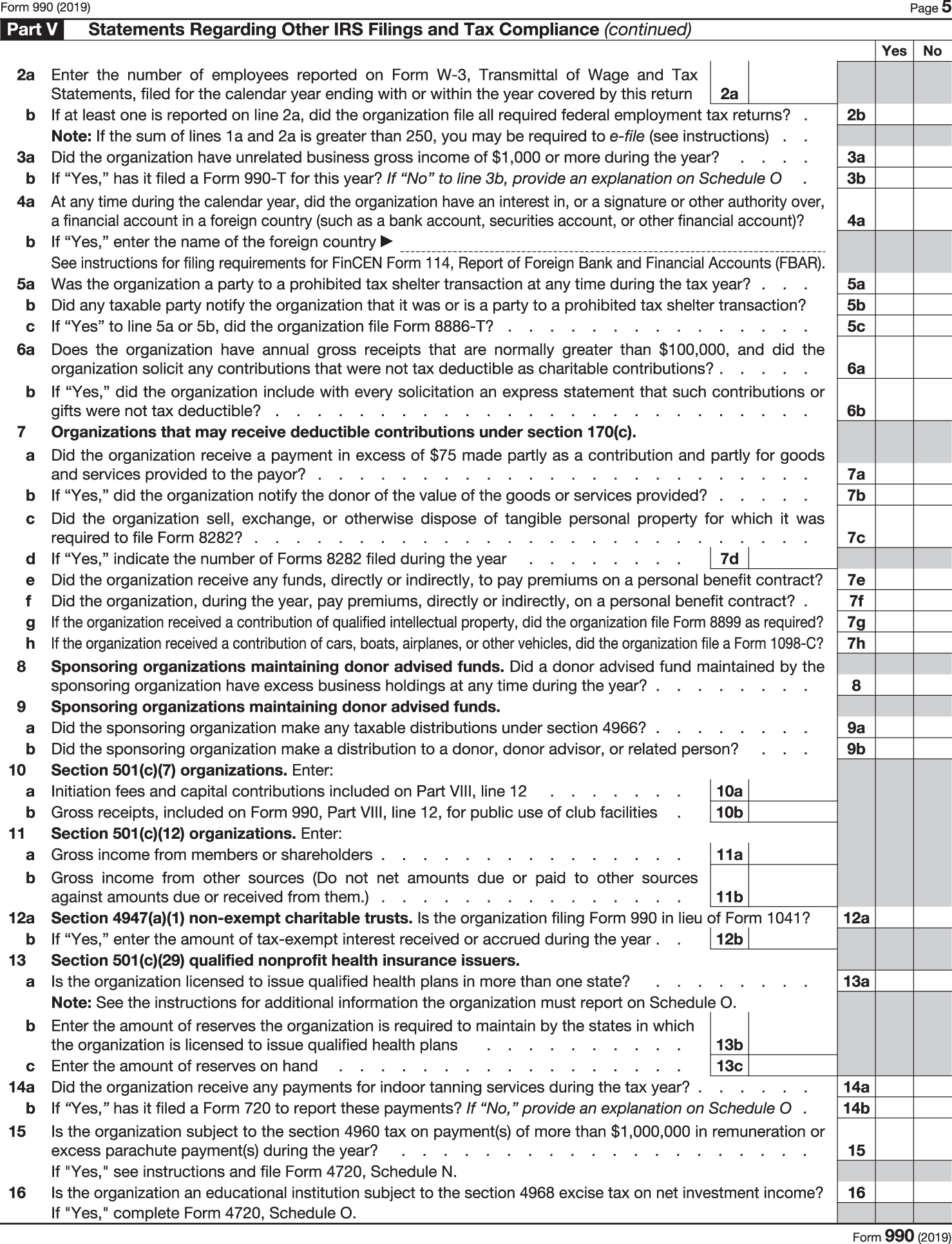

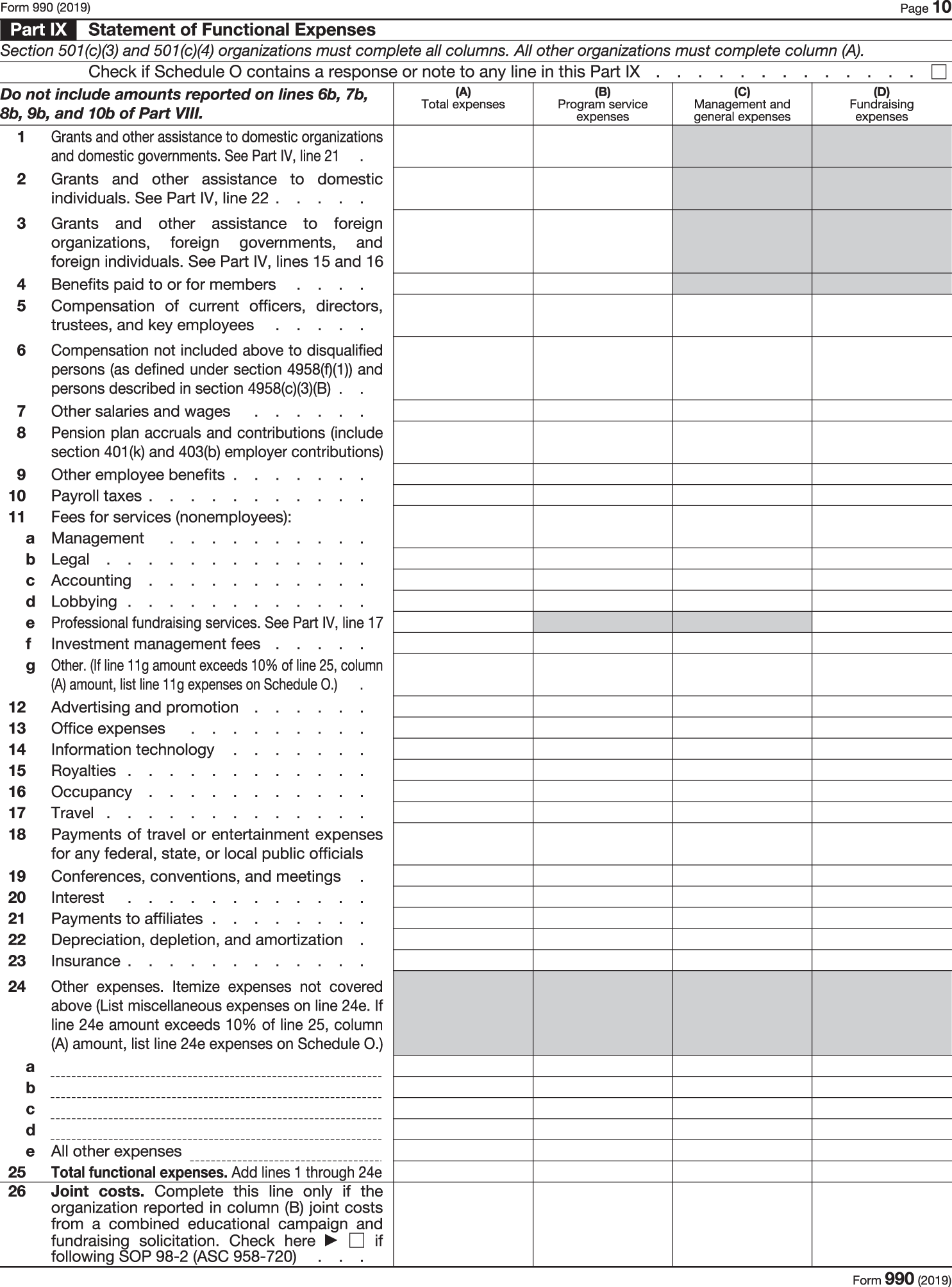

Exhibit 2 shows an example of the new Form 990. The following comments should be considered in preparing the form.

- The first fiscal year must end within twelve months of date of inception. The organization can choose any month as the end of its fiscal year, but once the election is made it cannot be changed easily in future years without notification to the Internal Revenue Service and in some instances, only with IRS approval. Thus, it is important during the first year to select the year-end carefully, keeping in mind the “natural” year-end for the organization. The election is made automatically when the first return is filed, which must be on a “timely” basis. This means the return must be filed within four and one-half months after the chosen year-end. The first return can cover a period as short as one month (or even a fraction of a month) or as long as twelve months. It cannot cover a period longer than twelve months, even though the first part of the period may have been a period of no activity. As a practical matter, many organizations elect a year-end following the conclusion of their first fundraising effort.

- The “employer identification number” is a number assigned by the Internal Revenue Service upon request by any organization. This number will be used on all payroll tax returns and on all communications with the IRS. It serves the same identification function that the Social Security number serves for an individual. The preparer of a return should always be careful to use the correct number. An employer identification number should be requested by an organization on Form SS-4 as soon as it is formed even if it has no employees. It takes the IRS a period of time to assign the number; if the organization must file a return before the number is received, it should put “applied for” in this space.

- The “tax-exempt status” section refers to the section of the Internal Revenue Code under which the organization was granted exemption. This reference will be in the “exemption letter.” A request for exemption should be made as soon as the organization is incorporated and is made on Form 1023 (for organizations that believe they are exempt under Sec. 501[c][3]) or Form 1024 (for other organizations). If an organization has applied for but not yet received exempt status, the preparer should check the box in Item F.

- Gross receipts” means total receipts, including total proceeds from the sales of securities, investments, and other assets before deducting the cost of goods sold or the cost of the securities or other assets. Gross receipts for the filing requirement test is not the same as total income. Total income normally would not include the gross proceeds from the sale of assets, but only the net profit or loss on such sale. The concept of gross receipts used in this return is a tax and not an accounting concept. If gross receipts are normally12 under $25,000, the rest of the return need not be completed.

Part I of the form provides summary information about the organization's revenues, expenses, assets, liabilities, and net assets. Many of the amounts that are reported in this summary come from various other parts of the form that provide additional details about these amounts. Also included in this summary is a brief description of the organization's mission and information about the number of independent voting board members that it has as well as the total of the voting board members.