21

LONG-LIVED ASSETS, DEPRECIATION, AND IMPAIRMENT

- Perspective and Issues

- Concepts, Rules, and Examples

- Disclosure Requirements

PERSPECTIVE AND ISSUES

Long-lived assets are those that provide an economic benefit to the organization for a number of future periods. GAAP regarding long-lived assets involves the determination of the appropriate cost at which to record the asset and the appropriate method to be used to allocate that cost over the relevant periods.

These assets are primarily operational assets, and they are broken down into two basic types: tangible and intangible. Tangible assets have physical substance and are categorized as follows:

- Depreciable;

- Depletable;

- Other tangible assets.

Intangible assets have no physical substance. Their value is found in the rights or privileges that they grant to the organization.

Most of the accounting problems involve proper measurement and timing of the transactions. Adequate consideration must be given to the substance of the transaction.

In addition, GAAP provides guidance related to accounting for the impairment or disposal of long-lived assets. These requirements are primarily contained in FASB ASC 360-10, which are described in greater detail later in this chapter. While these requirements address several different areas regarding asset impairment, their impact is greater on the accounting for long-lived assets that are disposed of by sale or by means other than a sale. Even though these types of transactions occur far less frequently in not-for-profit organizations than in commercial organizations, not-for-profit organizations must be cognizant of the requirements.

CONCEPTS, RULES, AND EXAMPLES

Property and equipment includes all long-lived tangible assets held by not-for-profit organizations, except collection items and assets held for investment purposes.

Long-lived assets commonly held by not-for-profit organizations include the following: (AICPA Guide, paragraph 9.02)

- Land;

- Land improvements, buildings and building improvements, equipment, furniture and office equipment, library books, motor vehicles, and similar depreciable assets;

- Leased property and equipment (capitalized in conformity with GAAP requirements for capitalized leases);

- Improvements to leased property;

- Construction in process;

- Contributed use of facilities and equipment (recognized in conformity with the “Contributions Received and Agency Transactions” subsection of FASB ASC 958-605).

Asset Cost

Long-lived assets include property and equipment and other assets held for investment or used in an organization's activities that have an estimated useful life longer than one year. The cost of a long-lived asset should be stated at acquisition cost, including all costs necessary to configure and position the asset at the location at which it will be used. Usually organizations set a minimum amount of an asset's cost for capitalization. For example, only those assets with a cost of $100 or more (or $500, $1,000, or other amount) are capitalized. The cost of a long-lived asset includes not only the asset's purchase price, but also any related sales tax, freight, installation and setup costs, and direct and indirect costs (including interest) incurred by an entity in constructing its own assets. Costs that are capitalized should not include routine repairs and maintenance costs that do not add to the utility of an asset. Long-lived assets should not be written up to reflect appraisal, market, or current values that are above cost.

Contributed Long-Lived Assets

Contributions of property, plant and equipment, or other long-lived assets should be recognized at fair value at the date of contribution. Unconditional promises to give those assets would be required to be recognized as contribution revenue under GAAP. If a donor stipulates how long a contributed long-lived asset must be used by the organization, the asset contribution should be reported as restricted support. The value of contributed long-lived assets should include all costs incurred by the organization to place the asset in service. Thus, the recorded value of the asset would consist of not only its fair value but also the related costs incurred by the not-for-profit organization to get it ready for use. Examples of such costs include the freight and installation costs of contributed equipment and cataloging costs for contributed library books. (FASB ASC 958-360-30-1)

NOTE: Many not-for-profit organizations liked the ability to apply a time restriction on donations for long-lived assets because in future years they were able to release temporarily restricted net assets to unrestricted to offset the depreciation expense that was recorded in unrestricted. When such a donation is recorded as part of net assets without donor restriction the year of donation reports a large increase in net assets, but depreciation expense then is recorded for the remaining useful life of the asset, which can be viewed as mismatching the benefit and the cost.

Property and equipment used in exchange transactions (other than lease transactions), such as federal contracts, in which the resource provider retains legal title during the term of the arrangement, should be reported as a contribution at fair value at the date received by the not-for-profit organization only if it is probable that the organization will be permitted to keep the assets when the arrangement terminates. The terms of such arrangements should be disclosed in notes to the financial statements.

Depreciation Methods

In accordance with the matching principle, the costs of fixed assets are allocated to the periods they benefit through a depreciation method. The method of depreciation chosen must result in the systematic and rational allocation of the cost of the asset (less its residual value) over the asset's expected useful life. The determination of the useful life must take a number of factors into consideration. These factors include technological change, normal deterioration, and actual physical usage. The method of depreciation is based on whether the useful life is determined as a function of time (e.g., technological change or normal deterioration) or as a function of actual physical usage.

Generally accepted accounting principles essentially recognize straight-line and accelerated methods of computing depreciation. While these methods are described below, not-for-profit organizations tend to use straight-line depreciation since there is seldom a tax advantage for using accelerated methods. Not-for-profit organizations that have operations in which it is important to measure profitability, as would a commercial enterprise, should consider whether accelerated methods of depreciation might be more appropriate for their purpose. In addition, when the nature of the asset (such as automobiles or computer equipment) means that it naturally loses more value earlier in its useful life, accelerated methods of depreciation may be more appropriate.

- Straight-line method. This method allocates cost less salvage value evenly over the asset's estimated useful life.

- Accelerated methods. These methods allocate cost disproportionately over the asset's useful life so that the early years are charged with most of the cost. The concept is that assets lose more of their value in the earlier years of their lives than they do when they become older. There are a number of acceptable accelerated depreciation methods, including the following:

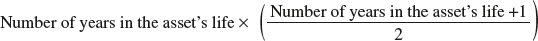

- Sum-of-the-years' digits. Under this method, depreciation is determined by multiplying the asset's cost less salvage value by a fraction in which the sum-of-the-years' digits is the denominator and the number of years remaining in the asset's life is the numerator. The sum-of-the-years' digits is determined by the following formula:

For example, the sum-of-the-years' digits for an asset with a seven-year life is 28 (i.e., 7 × [(7 + 1) ÷ 2] = 28), and 7/28 of the asset's cost would be depreciated in the first year, 6/28 of the asset's cost would be depreciated in the second year, and so on.

- Declining balance. Under this method, a depreciation rate that is a multiple of the straight-line depreciation rate is applied to the asset's net depreciable value. (Although the asset's salvage value is ignored in the depreciation calculation, the asset should not be depreciated below its salvage value.) For example, using the straight-line rate for an asset with no salvage value whose useful life is ten years would be 10% per year. Under the double-declining balance method, the depreciation rate would be “double” the straight-line rate or 20%, which would then be multiplied by the net book value (i.e., cost less accumulated depreciation) until the asset was depreciated down to its salvage value.

- Units-of-production. Under this method, depreciation is a function of the asset's total estimated production capability during its estimated useful life. This method is based on a formula, which can be expressed as follows:

- Sum-of-the-years' digits. Under this method, depreciation is determined by multiplying the asset's cost less salvage value by a fraction in which the sum-of-the-years' digits is the denominator and the number of years remaining in the asset's life is the numerator. The sum-of-the-years' digits is determined by the following formula:

Other depreciation methods. The following depreciation methods do not have general acceptance, although if they produce results that are not materially different from the acceptable methods described above, they might be considered for use by a not-for-profit organization (particularly the group [composite]) method, since it streamlines the depreciation calculation.

- Retirement method. The cost of the asset is expensed in the period in which it is retired.

- Replacement method. The original cost is carried in accounts and the cost of replacement is expensed in the period of replacement.

- Group (composite) method. This method averages the service lives of a number of assets using a weighted average of the units and depreciates the group or composite as if it were a single unit. A group consists of similar assets while a composite is made up of dissimilar assets.

Gains and losses are not recognized on the disposal of an asset but are netted into accumulated depreciation.

Partial-Year Depreciation

When an asset is either acquired or disposed of during the year, the full-year depreciation calculation is prorated between the accounting periods involved.

The Smart University, a calendar-year not-for-profit organization, acquired a printing machine on June 1, 2000, which cost $40,000 with an estimated useful life of four years and a $2,500 salvage value. The depreciation expense for each full year of the asset's life is calculated as:

| Straight-line | Double-declining balance | Sum-of-years digits | ||

| Year 1 | 37,500* ÷ 4 = 9,375 | 50% × 40,000 = 20,000 | 4/10 × 37,500* | = 15,000 |

| Year 2 | 9,375 | 50% × 20,000 = 10,000 | 3/10 × 37,500 | = 11,250 |

| Year 3 | 9,375 | 50% × 10,000 = 5,000 | 2/10 × 37,500 | = 7,500 |

| Year 4 | 9,375 | 50% × 5,000 = 2,500 | 1/10 × 37,500 | = 3,750 |

* (40,000 − 2,500)

Because the first full year of the asset's life does not coincide with the university's year, the amounts shown on the previous page must be prorated as follows:

| Straight-line | Double-declining balance | Sum-of-years digits | ||||

| 2000 | 7/12 × 9,375 = | 5,469 | 7/12 × 20,000 = | 11,667 | 7/12 × 15,000 = | 8,750 |

| 2001 | 9,375 | 5/12 × 20,000 = | 8,333 | 5/12 × 15,000 = | 6,250 | |

| 7/12 × 10,000 = | 5,833 | 7/12 × 11,250 = | 6,563 | |||

| 14,166 | 12,813 | |||||

| 2002 | 9,375 | 5/12 × 10,000 = | 4,167 | 5/12 × 11,250 = | 4,687 | |

| 7/12 × 5,000 = | 2,917 | 7/12 × 7,500 = | 4,375 | |||

| 7,084 | 9,062 | |||||

| 2003 | 9,375 | 5/12 × 5,000 = | 2,083 | 5/12 × 7,500 = | 3,125 | |

| 7/12 × 2,500 = | 1,458 | 7/12 × 3,750 = | 2,188 | |||

| 3,541 | 5,313 | |||||

| 2004 | 5/12 × 9,375 = | 3,906 | 5/12 × 2,500 = | 1,042 | 5/12 × 3,750 = | 1,562 |

As an alternative to proration, a not-for-profit organization may follow any one of several simplified conventions.

- Record a full year's depreciation in the year of acquisition and none in the year of disposal.

- Record one-half year's depreciation in the year of acquisition and one-half year's depreciation in the year of disposal.

These alternatives are far less tedious than the detailed calculations described above. Not-for-profit organizations should seriously consider using one of the simpler alternatives.

Changes in Depreciation Calculations in Estimated Useful Life and Salvage Value

A change in the estimated useful life and salvage value of an asset being depreciated should be accounted for as a change in estimate. The change should be recorded in the current period change in net assets or the current and future changes in net assets if the change affects both current and future periods. A change in the method used to depreciate assets should be accounted for as a change in accounting principle. A change in accounting principle is accounted for by including the cumulative effect of the change as of the beginning of the year of the change in the current period change in net assets. Accounting changes are more fully discussed in Chapter 27.

Impairment of Long-Lived Assets

Not-for-profit organizations need to consider the requirements of GAAP related to accounting for the impairment or disposal of long-lived assets, found at FASB ASC 360-10, when preparing financial statements in accordance with GAAP. As a practical matter, it is not desirable for a not-for-profit organization to have its net assets overstated because of the inclusion of assets that are overvalued. On the other hand, not-for-profit organizations tend not to focus on cash flows from their assets, so that application of GAAP requirements can be difficult for these organizations. While a commercial organization may be motivated to write down a nonproductive asset all in one year (to keep depreciation expense from changing earnings in future years), not-for- profit organizations do not have this motivation for one-time earnings write-offs. That is why it is important for not-for-profit organizations' financial statement preparers (and their auditors) to be cognizant of requirements related to impairment so that impaired assets are properly stated in the financial statements. It's also important to note from the following discussion that this is really a two-step process. First, it is determined whether an asset is impaired. Second, the amount of the write-down to reflect the impairment is determined.

Recoverability of an Asset

FASB ASC 360-10-35-21 states that the following events or circumstances may indicate that the recoverability of an asset's or asset group's carrying value should be assessed:

- Significant decrease in the asset's or asset group's market value;

- Significant change in the asset's or asset group's use or physical condition;

- Significant adverse changes in legal factors or business climate or an adverse action or assessment by a regulator;

- Costs to acquire or construct an asset or asset group that significantly exceed original expectations;

- Continuing decreases in net assets or cash flow losses associated with an asset or asset group used to produce revenue from exchange transactions;

- A current expectation that more likely than not, a long-lived asset or asset group will be sold or otherwise disposed of significantly before the end of its previously estimated useful life.

For purposes of recognition and measurement of an impairment loss, a long-lived asset or assets should be grouped with other assets and liabilities at the lowest level for which identifiable cash flows are largely independent of the cash flows of other assets and liabilities.

If there is doubt about the recoverability of an asset or asset group, an assessment must be made as to whether the value of the asset has been impaired, using reasonable and supportable assumptions. In testing for impairment, expected cash flows from continuing to use the asset and its eventual disposition (undiscounted and without interest) should be estimated. If it is not possible to estimate cash flows from a specific asset, assets should be grouped at the lowest level from which there are identifiable cash flows.

Estimates of future cash flows used to test the recoverability of a long-lived asset or asset group should only include the future cash flows that are directly associated with and that are expected to arise as a direct result of the use and eventual disposition of the asset or the asset group. The estimates should not include interest charges that will be recognized as an expense when incurred.

The estimates as to the determination of future cash flows that are used to test recoverability should be based on the organization's assumption about the use of the asset or asset group and should consider all available evidence. If alternative courses of action to recover the carrying amount of a long-lived asset or asset group are under consideration (or if a range is estimated for the amount of possible future cash flows associated with the likely course of action), the likelihood or probability of the outcomes should be considered.

In addition, the estimates of future cash flows should be made for the remaining life of the asset or asset group to the organization. The remaining useful life of an asset group is based on the remaining useful life of the primary asset of the asset group. The primary asset is the most significant component asset of the asset group from which the asset group derives its cash flow generating capacity.

The future cash flow calculations described here should be based on the existing service potential of the asset or asset group at the date that it is tested. The service potential encompasses the remaining useful life, cash flow generating capacity, and, for tangible assets, physical output capacity. These cash flow calculations should also consider cash flows associated with future expenditures necessary to maintain the existing service potential of a long-lived asset or asset group.

If the undiscounted cash flows that are expected over the remaining useful life of the asset exceed the asset's carrying amount, the asset is not considered impaired. If the carrying amount is higher, then the asset is considered to be impaired and the amount of the impairment loss should be measured in the following way:

- An impairment loss should be recorded equal to the amount by which the asset's carrying amount exceeds its fair value.

- After an impairment has been recognized, the asset's reduced carrying amount becomes its new cost. Subsequent recoveries of the impairment loss due to increases in the asset's fair value should not be recognized.

An asset being evaluated for possible impairment may not produce cash flows independently of other asset groupings in certain limited circumstances. (FASB ASC 360-10-35-24) In these cases, the asset group for that long-lived asset should include all assets and liabilities of the organization.

Impairment occurs if the book value of long-lived assets is determined not to be recoverable. In a total impairment, the obsolete asset and related depreciation are removed from the accounts and a loss is recognized for the difference. If a partial impairment of a depreciable asset results, the asset should be written down to a new cost basis. That new cost basis is then depreciated over the remaining life of the asset. The journal entry follows:

| Accumulated depreciation | xxx | |

| Loss due to impairment | xxx | |

| Asset | xxx |

The loss amount would appear in the statement of activities as a component of continuing operations.

Assets to Be Disposed Of

Long-lived assets to be sold generally would be carried at the lower of cost or fair value less cost to sell.

A long-lived asset to be sold should be classified as held for sale in the period in which all of the following criteria are met: (FASB ASC 360-10-45)

- Management, having the authority to approve the action, commits to a plan to sell

the asset.

- The asset is available for immediate sale in its present condition subject only to terms that are usual and customary for sales of such assets.

- An active program to locate a buyer and other actions required to complete the plan to sell the asset have been initiated.

- The sale of the asset is probable and the transfer of the asset is expected to qualify for recognition as a completed sale, within one year (there are certain exceptions to the one-year requirement).

- The asset is being actively marketed for sale at a price that is reasonable in relation to its current fair value.

- Actions required to complete the plan indicate that it is unlikely that significant changes to the plan will be made or that the plan will be withdrawn.

If an asset does not meet all of these criteria (or if it will be disposed of by means other than a sale), the asset should be classified as held and used and subject to the impairment test described earlier in this section. If an organization commits to abandon a long-lived asset before the end of the asset's previously estimated useful life, depreciation estimates should be revised to reflect the use of the asset over its shortened useful life. A long-lived asset that has been temporarily idled should not be accounted for as if it were being abandoned.

Asset Retirement Obligations

FASB ASC 410-20 provides guidance for accounting for liabilities incurred when assets are retired. The requirements apply to legal obligations associated with the retirement of a tangible, long-lived asset that results from the acquisition, construction, or development and/or the normal operation of a long-lived asset. A legal obligation is considered an obligation that a party is required to settle as a result of an existing or enacted law, statute, ordinance, or written or oral contract or other means of legal construction.

GAAP requires that an organization (whose scope includes not-for-profit organizations) recognize the fair value of a liability for an asset retirement obligation in the period in which it is incurred if a reasonable estimate of the fair value can be made. If a reasonable estimate of the fair value cannot be made in the period that the asset retirement obligation is incurred, the liability should be recognized when a reasonable estimate of the fair value can be made.

When the organization initially recognizes a liability for an asset retirement obligation, it should capitalize an asset retirement cost by increasing the carrying amount of the related long-lived asset by the same amount as the liability. The organization would subsequently allocate the asset retirement cost to expense using a systematic and rational method over its useful life. On the other hand, GAAP specifies that the organization is not precluded from capitalizing an amount of asset retirement cost and allocating an equal amount to expense in the same accounting period. For example, an asset is acquired with a ten-year useful life. As the asset is operated, the organization incurs one-tenth of the liability for the asset retirement obligation each year. The organization can capitalize and then expense one-tenth of the asset retirement costs each year.

Since the estimate of the fair value of the future obligation will involve applying present value techniques to the calculation of the estimated obligation, the liability will increase due to the passage of time. The organization should use the effective interest method to measure this increase in the liability, using a credit-adjusted, risk-free rate at the time that the liability is measured. The amount that the liability increases each year should be charged to expense, which is referred to as “accretion expense.”

In FASB ASC 410-20-25, the FASB clarifies that the presence of some uncertainty about the timing of an asset retirement is not an exemption from having to apply the accounting requirements for asset retirement obligations discussed above.

The FASB ASC Master Glossary provides that the term “conditional asset retirement obligation” refers to a legal obligation to perform an asset retirement activity in which the timing and/or method of settlement are conditional on a future event that may or may not be within the control of the organization. FASB ASC 410-20-55 provides implementation guidance for the asset retirement obligation accounting requirements, including the example of a conditional asset retirement obligation as the regulatory responsibility to handle and dispose of asbestos in a special manner if the asbestos is exposed when a building undergoes major renovations or is demolished. If there are plans or the expectation of plans (such as because of obsolescence) to undertake a renovation that would require removal of the asbestos, a not-for-profit organization will generally have to recognize a liability for the cost of removing and disposing of asbestos.

GAAP specifies that an entity shall recognize a liability for the fair value of a conditional asset retirement obligation if the fair value of the liability can be reasonably estimated. An entity is required to recognize the fair value of a legal obligation to perform asset retirement activities when the obligation is incurred—generally upon acquisition, construction, or development and/or through the normal operation of the asset.

GAAP provides that an entity should identify all its asset retirement obligations. If an entity has sufficient information to reasonably estimate the fair value of an asset retirement obligation, it must recognize a liability at the time the liability is incurred. An asset retirement obligation would be reasonably estimable if (a) it is evident that the fair value of the obligation is embodied in the acquisition price of the asset, (b) an active market exists for the transfer of the obligation, or (c) sufficient information exists to apply an expected present value technique. An expected present value technique incorporates uncertainty about the timing and method of settlement into the fair value measurement. However, in some cases, sufficient information about the timing and/or method of settlement may not be available to reasonably estimate fair value.

An organization would have sufficient information to apply an expected present value technique, and therefore an asset retirement obligation would be reasonably estimable, if either of the following conditions exists:

- The settlement date and method of settlement for the obligation have been specified by others. For example, the law, regulation, or contract that gives rise to the legal obligation specifies the settlement date and method of settlement. In this situation, the settlement date and method of settlement are known and therefore the only uncertainty is whether the obligation will be enforced (that is, whether performance will be required). Uncertainty about whether performance will be required does not defer the recognition of an asset retirement obligation because a legal obligation to stand ready to perform the retirement activities still exists, and it does not prevent the determination of a reasonable estimate of fair value because the only uncertainty is whether performance will be required. In certain cases, determining the settlement date for the obligation that has been specified by others is a matter of judgment that depends on the relevant facts and circumstances.

- The information is available to reasonably estimate:

- The settlement date or the range of potential settlement dates;

- The method of settlement or potential methods of settlement;

- The probabilities associated with the potential settlement dates and potential methods of settlement.

Examples of information that is expected to provide a basis for estimating the potential settlement dates, potential methods of settlement, and the associated probabilities include, but are not limited to, information that is derived from the entity's past practice, industry practice, management's intent, or the asset's estimated economic life. In many cases, the determination as to whether the entity has the information to reasonably estimate the fair value of the asset retirement obligation is a matter of judgment that depends on the relevant facts and circumstances.

DISCLOSURE REQUIREMENTS

Long-Lived Assets and Depreciation

GAAP-basis financial statements should include the following disclosures about long-lived assets and depreciation:

- Description of the organization's capitalization policy, including basis of valuation.

- Balances of major classes of depreciable assets for each period presented.

- Depreciation expense for each period presented and accumulated depreciation as of the end of each period presented.

- Description of the methods used to compute depreciation on each major class of depreciable assets and range of estimated lives of the assets.

- Donor-restricted assets that are to be used to invest in property and equipment.

- Property and equipment not recorded on the statement of financial position because its title is held by grantors, although the asset is used by the not-for-profit organization. Property and equipment acquired with restricted assets and whose title may revert to a third party should also be disclosed.

- Property and equipment pledged as collateral or subject to a lien.

- Donor-imposed or legal restrictions on the use of property and equipment or the proceeds from the disposition of property and equipment should be described in the footnotes.

- Amounts capitalized for works of art, historical treasures, and similar items that do not meet the definition of a collection. (FASB ASC 958-360-50)

Impaired Long-Lived Assets

If an impairment loss is recognized in the statement of activities, the following disclosures should be included in the notes to the financial statements: (FASB ASC 360-10-50)

- Description of the impaired assets and the situation surrounding the impairment;

- Amount of impairment loss (if not presented separately on the statement of activities) and the methods used to determine fair value;

- When more than one impairment loss is not reported separately or parenthetically, the caption where the losses are aggregated;

- The business segment affected, if applicable.

Assets to Be Disposed Of

Disclosures to be made in the case of long-lived assets either sold or classified as held for sale are as follows: (FASB ASC 205-20-50)

- Description of the facts and circumstances leading to the expected disposal, the expected manner and timing of the disposal, and the carrying amount(s) of the major classes of assets and liabilities included as part of a disposal group, if not presented on the face of the financial statements.

- The gain or loss recognized, and if not presented separately on the face of the statement of activities, the caption in the statement of activities that includes the gain or loss.

- Amounts of revenue and pretax profit or loss reported in discontinued operations, if applicable.

- The segment in which the long-lived asset is reported, if applicable.

Asset Retirement Obligations

The following disclosures should be provided for asset retirement obligations: (FASB ASC 205-20-50)

- A general description of the asset retirement obligations and the associated long-lived assets.

- The fair value of assets that are legally restricted for purposes of settling asset retirement obligations.

- A reconciliation of the beginning and ending aggregate carrying amount of asset retirement obligations showing separately the changes attributable to:

- Liabilities incurred in the current period;

- Liabilities settled in the current period;

- Accretion expense;

- Revisions in estimated cash flows, whenever there is a significant change in one or more of those four components during the reporting period.

- If the fair value of an asset retirement obligation cannot be reasonably estimated, that fact and the reasons therefor shall be disclosed.