Information sharing and integration

Documents as information assets

Sharing information on the Web

Attention information workers!

Are you tired of cutting and pasting from one document to another?

Are you frustrated because people outside your work group can’t find your reports?

Are you concerned that your spreadsheet analyses may not be using the latest data?

Do you have that tired, worn-out feeling?

Well, we can’t help you with the last item, unless you’ve been losing sleep over the first three! But Microsoft has a cure for those: They’ve added a powerful dose of the miracle ingredient XML to your favorite Office tools.

XML is a neutral way to represent data in a computer file. By “neutral” we mean that XML is not associated with a single vendor’s computer programs, nor is it limited to a particular structure or type of information. XML is therefore ideal for sharing information among programs. In fact, it is recommended for that purpose by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and is supported by hundreds of products from every important software vendor.

XML allows you to share the data in your Office documents in new and more useful ways. It can help to automate routine drudgery. It can allow your documents to become first-class information citizens, managed and protected like the other data assets in your organization.

As an example, let’s look at the large and successful (and utterly imaginary) Worldwide Widget Corporation (NASDAQ: W2C) before it began using XML.

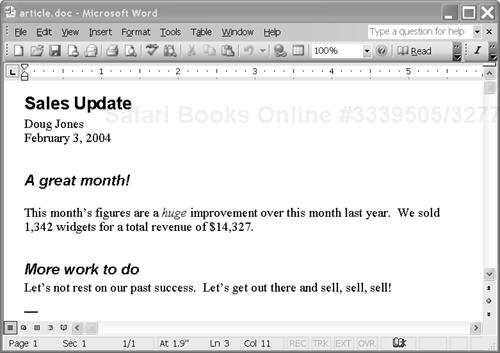

Doug writes a monthly Sales Update article for the company newsletter that is widely read and appreciated for its up-to-the-minute data and inspirational prose. He types the article into Microsoft Word and saves it as a .doc file.

He formats the article using different styles; for example, “Heading 1” for the title and “Heading 2” for the section headers. He also puts the author name and date in bold. (See Figure 1-1.)

Doug then submits the article by email to Denise, who is responsible for compiling the newsletter. Denise opens all the article documents that are submitted and cuts and pastes them into a new Word document. She reassigns styles to the various article titles and section headers to make them consistent.

Denise fixes any problems with the submissions, such as articles that are missing author names or dates. She does some general formatting, such as putting the company logo in the corner and changing the margins. She then saves her new .doc document in a directory named “newsletters” and distributes it by email to the entire company.

Although this approach accomplishes the goal of getting the newsletter out, it has several drawbacks:

rendered content

When Doug created his article, his focus was on creating a formatted rendition. He applied styles so that a human reading the article could see that the author is “Doug Jones” and that the article date is February 3, 2004. A computer, though, would have no way of knowing this. As a result, there is no automated way to search the articles, say, for all articles whose author is Doug Jones, or all articles that were written after a particular date. In addition, there is no way to enforce rules for the article documents to make them consistent; for example, that at least one author is required, or that the title must be between 10 and 72 characters long.

inflexible rendition

Because the style information is tied directly to the content, there is a lot of repetitive manual reformatting. To change the style of all the author names, each author name needs to be changed separately. If the newsletter is to be presented in more than one way – for example, both as a printed document and as a Web page – the content of the document needs to be manually reformatted and stored redundantly. Templates could alleviate this problem somewhat, but only when the alternative renditions have similar structures.

lack of integration with enterprise data

Incorporating data from other parts of the organization requires either precise manual effort, or significant programming skills. For example, Doug needs to do careful, error-prone copying and reformatting to get the current sales statistics into his article every month.

proprietary format

The proprietary

.docformat of Microsoft Word means that the text written by Doug, which may be a useful reference, is never integrated into a company database or content management system. It probably is abandoned on a file server somewhere.

All of these issues can be addressed by using XML in Office.

These days, no one seems to doubt that data is a valuable company asset. Business data that is more up-to-date and accessible can lead to more accurate planning, improved customer service, and more efficient business processes.

Technologists therefore treat data with great care. They carefully design databases and make them available to a variety of business processes. They organize these databases so that the data can be quickly and easily queried, joined, sorted and summarized. They protect them using security measures and disaster recovery plans.

All too often, though, this great care is extended only to databases containing operational data about customers, products, sales, and suppliers. There is a vast wealth of equally important data, stored in documents, that is largely ignored. It may include legal contracts, Web pages, memos, budget spreadsheets, product specifications, press releases, marketing brochures, conference presentations, product manuals and company policies and procedures.

These documents are often isolated and inaccessible. They are stored in proprietary binary formats on file servers, using inconsistent directories, names and versioning strategies. They are in rendered form, and therefore cannot be searched, summarized or indexed consistently in any meaningful way.

To coin a phrase, the data in documents isn’t integrated with the other data of the enterprise. Using XML in Office allows that data to be integrated. Ironically, XML enables integration by separation:

Separating the document representation from the software.

Because XML is a non-proprietary, open file format, a wide variety of software tools can act on your documents. This means that these documents can be integrated into your business processes just like any data in a database.

Separating the data content from style information.

In order to use your data effectively, you need to understand what it means rather than just what it looks like. XML lets you identify and describe the content of your document, not just its outward appearance.

Without delving too far into the technical details just yet, let’s take a closer look at how these two separations can help you.

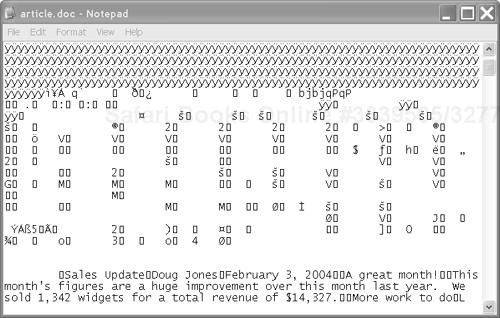

Previous versions of Office primarily used proprietary formats, such as .doc and .xls files, to store documents. These binary formats could effectively be used only by the software that created them. If you’ve ever tried to open up a .doc file in Notepad, as shown in Figure 1-2, you know that the format is indecipherable to the human reader, and it is largely indecipherable to other software applications as well. Only the Microsoft Word application knows how to make complete sense of it.

We are so accustomed to this state of affairs that we do not think of the documents separately from the software. A document is a “Word document” or an “Excel worksheet” that has no use outside Office.

XML, in contrast, is a non-proprietary character-based data representation that can be processed both by humans and, more importantly, by hundreds of computer programs. When an Office document is saved as XML, it can be used by other tools in addition to Microsoft Word.

The document is no longer a “Word document”, but an XML document that can be edited in, or processed by, whatever tool makes the most sense for a given task. The document can be queried, transformed, sorted, viewed on the Web, passed around in e-commerce business processes, validated, stored in a database, shared with non-Office users and archived and indexed.

Separating the document format from the software makes the Office software more useful, too. Suddenly Office applications can be used to edit a wider variety of documents. The analytical tools of Excel can be used on any data that can be represented as XML, not just data that is stored in an Excel worksheet. Word can be used to edit any XML document.

Example 1-1 shows Doug’s article represented as an XML document. Tags, such as <title> and </title>, are used to mark the start and end of data elements. Doug didn’t type those tags; Word did it for him. In fact, Office users don’t even have to see them on the screen if they don’t want to.

Example 1-1. Doug’s article, represented in XML

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="yes"?>

<article xmlns="http://xmlinoffice.com/article"

type="sales" id="A123">

<title>Sales Update</title>

<author>Doug Jones</author>

<date>February 3, 2004</date>

<body>

<section>

<header>A great month!</header>

<para>This month's figures are a <em>huge</em> improvement over

this month last year. We sold 1,342 widgets for a total revenue of

$14,327.</para>

</section>

<section>

<header>More work to do</header>

<para>Let's not rest on our past success. Let's get out there

and sell, sell, sell!</para>

</section>

</body>

</article>

There is more information in Chapter 2, “XML concepts for Office users”, on page 20.

One thing you may have noticed about our XML example is the absence of formatting information. Nothing in the document tells an application to indent a particular paragraph, display a word as bold, or use any particular font for a header. Rather, the tags convey the meaning and structure of the document.

There are tags that identify simple data elements, such as date and title. There are also elements with complex structures, such as para and section.

The vocabulary in the tags was created just for articles, which assures that there is a way to identify everything the company thinks is important about an article.

Separating the data content of the document from its formatting is one of the important principles of XML. The content itself is stored as an XML document, and different stylesheets are applied to it to achieve different renditions. This separation has two important benefits: self-describing content and flexible rendering.

Describing the data rather than the style means that applications can identify what the document contains rather than what it looks like. The document becomes self-describing.

For example, in Doug’s article, we know exactly where to find the author name, because tags identify it as an author element. Otherwise, we might have to assume that the author name is “that thing in bold on the second line”.

Being able to identify data elements is powerful because it allows you to perform all kinds of automated functions on the document, such as:

searching for all articles whose author is “Doug Jones” (not just articles that contain the words “Doug Jones”)

specifying rules for article documents, such as “at least one author must be specified”, or “the title must be between 10 and 72 characters long”

automatically generating a list of all the article titles, authors and dates

generating a summary calculation of the average number of paragraphs in an article

Another advantage of separating data from style is that it provides flexibility in the formatting. If the same material is to be presented in more than one way, it does not have to be written (and maintained) multiple times.

For example, suppose Doug’s article is to appear in a printed newsletter and also be available on the Web. Perhaps the Web version has links and some sidebar information that does not appear in the print version. The look is different, too: the fonts are larger on the website, and the text is continuous rather than being broken into pages.

In this situation, the unrendered (abstract) data content is in a single XML document. There are two different stylesheets that create different renditions of the content. If the content must be changed, it only needs to be modified in one place.

You can also create different subsets or views of the same data. For example, if:

Different readers are interested in different aspects of the document.

Security concerns allow only part of an article to be read by a particular audience.

On the Web, you want to provide just the first paragraph of the article as a tease before requiring a reader to sign up for a service.

The document contains information that is not normally presented, such as search keywords, or information about who last updated the document and when.

In each of these situations, you can write a stylesheet that shows only the relevant parts of the article.

Supporting multiple renditions of the same content is increasingly necessary. Browsing the Web has come to mean a lot more than just looking at HTML pages in a Web browser on a PC. People now use telephones, PDAs and other handheld devices to browse the Web, and they are inventing new ways of using the Web all the time. Different devices have different screen sizes and memory limits, and therefore need information presented in a different way.

When style information is kept separate, it is easier to change it without affecting the content. For example, if you decide you want the author name to appear in italics, you can simply change the stylesheet once, rather than restyling the author name in every article document.

We have seen that XML in Office can help integrate data by making it easier to share, search and process. This data sharing goes beyond making data in Office documents available to the enterprise. XML also makes it easier to import enterprise data into Office documents for reuse and analysis, and even to use Office as a front-end to manage enterprise data.

You know the data – that valuable information about sales, customers, products, inventory, and employees. It is stored in database management systems, software packages (such as ERP and accounting packages) and files on a variety of computer platforms around the organization. If you are lucky, you can at least access this data in useful ways using a reporting tool or custom application provided by your IT department. If you are not so lucky, you get canned reports that aren’t exactly what you need and cannot be reused. Even worse, you have to get an IT person involved every time you want to query the data in a new way.

That is all changing. Enterprise data is rapidly becoming available as XML. All major relational database vendors now offer an XML front-end, which allows data to be queried and extracted as XML. A lot of information that is stored and managed by ERP and other software packages can be exported as XML. In addition, there is a whole body of data whose native format is XML: both in XML databases and as documents in repositories and file systems.

Remember Doug? He includes the past month’s sales figures in his article for the newsletter. Before XML he went to an intranet site and ran a report that returned the results in a Web page. He then cut and pasted the information into his article in Word.

He had to do some reformatting, because the data came back without dollar signs and the columns did not line up properly when pasted into Word. In addition, there were some figures, such as total sales and average amount of sale, which he calculated by hand.

For Doug to do this once, with relatively static data, would not be a huge amount of extra work. But Doug includes some or all of the sales figures in his article every month. He had to go through this same cutting, pasting and reformatting process repeatedly. This was tedious, and prone to error. In addition, the data is updated regularly. In order to have the most up-to-date numbers in the article, he needed to wait until the last minute or redo the formatting again before publication.

Office 2003 has greatly improved this situation using XML. All Doug needs to do now is click a button in the Word document to import the sales figures, formatted the way he wants them. When he wants to refresh the data, it is as simple as clicking that button again.

Of course, there is some setup required. A link to the database that stores the sales data needs to be created to generate an XML document. Also, a mapping needs to be defined between the resulting XML and its formatting in Word. For repetitive tasks like this one, it is well worth the time spent for setup.

Another reason to import enterprise data is to allow the use of the familiar Office environment for data analysis and reporting. In particular, Excel has tools for performing complex, multi-step mathematical calculations on data, and for easily creating graphs and charts. Users are already familiar with Excel’s features and want to continue to use them rather than learn new reporting tools for different kinds of enterprise data.

Before XML, program code had to be written before Excel could import anything but text files that contained tabular data (flat files). And those had to be reformatted, just like Doug’s sales figures.

Importing XML does not require program code. Moreover, it allows Excel to import from a large number of possible data sources, without users having to understand the technical details of those sources.

The enterprise data is imported into areas of Excel worksheets that were previously set up to analyze that kind of data. For example, Doug could create a spreadsheet to generate graphs of the sales figures, as well as summary statistics. He could import the latest sales figures with a single click each month, and the graphs and statistics would automatically be updated.

One of the exciting new capabilities of Office is not just reading enterprise data, but also acting as a front-end to create and update it. You can use Word, Excel and the new forms tool, InfoPath, for this purpose. With them you can create new business documents and data that you can store in a database or feed automatically to non-Office applications.

For example, Ellen works in the accounting department of Worldwide Widget Corporation. The company uses an accounting package that allows the import of transactions from XML documents. Employees used to fill out their monthly expense reports in Excel and email them to Ellen. Ellen checked the expense reports and entered the totals manually into the accounting package in order to issue reimbursement checks.

This worked out fine when there were only 15 traveling employees, but as the company grew, the task became unmanageable. There was the problem of invalid expense reports; employees often entered invalid dates or cost center codes. There was also the extra work of entering information into the accounting system, a process that was time consuming and subject to human error. In addition, there was very little querying and reporting capability.

Ellen considered purchasing a Web-based expense reporting tool that employees could use when they are on the road. Instead, when XML in Office became available she realized that the employees could use it to create expense reports. She identified the cells in the Excel expense report as elements in the XML vocabulary required by the accounting package, created a set of validation rules, and rolled it out to the employees.

Expense reports are now submitted as XML documents, although the employees continue to create them with the same tag-less Excel spreadsheet. Not only can Ellen validate and query these new expense reports far more easily, she can automatically import them into the accounting system.

In situations like this one, Microsoft Office has huge potential as a simple, inexpensive XML editing tool. It requires no additional software for the users. The minimal amount of setup needed does not require advanced programming skills.

So far, we have looked at information integration within a single organization. With the arrival of the Web, companies have increasingly focused on information sharing among organizations.

Traditionally, companies wishing to share business data either did it the old-fashioned way, by printed reports, phone calls and faxes, or by using expensive EDI systems. The Web has completely changed the face of business by making it possible to share information – and therefore conduct business transactions – far more easily using a standard set of open protocols. Organizations share business documents such as product catalogs, purchase orders and invoices via the Web. Almost invariably the transactional documents are represented in XML.

In addition to passing XML documents back and forth over the Internet, businesses have begun to share data with a new class of software called Web services. Web services allow applications to communicate with one another (and even discover each other!) without human involvement.

For example, a provider may offer a Web service that returns a stock quote, or the current exchange rate for a particular pair of currencies. A Web service could also be something more complex, such as a service that accepts or places an order. Other applications can execute these services over the Web without any human intervention.

Obviously, not all Web services are intended for the public at large. Some are available only to partners with whom a business relationship already exists. But public or private, the Web services software works the same way.

Web services use XML to represent requests to a service as well as the information that the service returns. As a result, you can integrate Microsoft Office with XML Web services. You can use InfoPath, Word and Excel to enter inputs to many Web services and to display the results.

You can request information from a trusted source on the Web, and have it automatically included in an Office document. At Worldwide Widget Corporation, many of the sales reps and consultants travel internationally. When filling out their expense reports, they enter the currency in which their expenses were paid and the exchange rate, on that date, in US dollars.

Of course, it is possible for Ellen to direct the employees to a particular website and have them manually look up the exchange rate. However, it would be more efficient and accurate to have the exchange rate included in the expense report automatically. By using Excel to request the rate from a Web service, the consultants can retrieve it and apply it to the expense item.

In 1.3.4, “Office as an enterprise data front-end”, on page 16, we talked about using Office as a front-end editor for an enterprise application. This use of Office is not limited to internal applications; you can use it across the Web as well.

Worldwide Widget Corporation buys parts from a huge number of suppliers, large and small. The smaller suppliers have no real e-commerce systems in place, although they do have PCs in their offices and access to the Web. They receive purchase orders from Worldwide and send it invoices, by phone, fax and email.

Worldwide wants to move all the suppliers over to a Web-based ordering system because it is cheaper and less prone to error than the manual process. It develops a set of Web services that allow a supplier to retrieve XML purchase order documents and submit XML invoice documents.

The medium and large suppliers have IT departments that can write code to call these Web services automatically from their enterprise accounting systems. The code processes the purchase orders and generates the invoices.

The small suppliers, unfortunately, don’t have such systems, so they need a human interface to the Web services. Worldwide Widget could develop a Web-based front-end that would allow them to log on and view their purchase orders and create invoices. However, that would require software development skills and time, which are in short supply.

Instead, Worldwide designs InfoPath forms for the invoices and purchase orders. They allow the small suppliers to display the POs and prepare invoices that can be submitted as XML documents.

Now you’ve learned about some of the potential uses for desktop XML. Perhaps some of the scenarios described in this chapter seem familiar, and address goals you have for your own documents: better data sharing, self-describing documents, flexible rendering, and integration with enterprise data stores and the Web.

In the next chapter, we’ll go into some more detail about XML. We’ll cover the basic concepts that are relevant to its use with Office.

Then we’ll complete our introduction with a chapter on all the XML-enabled products in the Office suite, with examples of their XML capabilities.