6

E Is for Establish Rapport: Getting People to Want to Like You

The question I am asked most often after people find out I interrogated members of the Taliban and al Qaeda is “What was it like being a woman and talking to those guys?” They all want to know if they disrepected me or if I felt in any way at a disadvantage because of my sex. I tell people it was great because I was almost considered to be a third gender. Yes, I am a woman, but in their eyes I was an American military member who happened to be female. They didn’t look at or treat me the same way as they often did the women in their own cultures. I had a huge advantage being a “third gender”; in fact, I would bet that any female interrogator would tell you the same thing. Think about it: I was not a big, intimidating male Marine; I was a small, empathetic but authoritative female, so the detainees felt more relaxed with me. They didn’t have their guards up, as they would with a male interrogator. This is not to say my male counterparts were not as or even more successful than I. Many were, especially those who had similar cultural backgrounds as some of the detainees or spoke their language. (If I could go back and do it again, I would learn Arabic. My college German and Italian languages didn’t do my any favors at GTMO, unfortunately. I learned some Arabic while I was there, but if I had known more it would have given me even more common ground with prisoners.)

A funny thing happened one day regarding Arabic. After hours, days, and weeks of interrogating Arabic-speaking detainees, I began to pick up on some key words and phrases. During one interrogation I understood the detainee’s answer in Arabic and, without waiting for my interpreter to translate, I launched into another follow-up question. The detainee looked at me in surprise and became angry. He said, “You lie! You speak Arabic!” I had to explain that I didn’t, and that just as they were learning English, I was learning their languages. It took a long time for me to regain his trust; lesson learned on my part: Wait for your interpreter to translate!

I was able to gain the detainees’ respect through multiple methods. First, I gained it through the respect I was shown by others in authority. My older male interpreter respected me, the male prison guards respected me, and other male military and civilians respected me. People tend to respect those who are respected by others. Having a background in anthropology and archaeology also helped me identify and bridge some of those cultural differences, but even so, I had never stepped foot in the Middle East and I couldn’t speak any of the languages (outside of the few words and sayings I learned while I was there). So how was I able to build rapport with my detainees through common ground? I had none, or so I thought.

First I thought about what we did have in common, me and this foreign fighter for al Qaeda who loathes the United States and everything it stands for. Oh, I know! We’re both human beings! If I treat him like a human then hopefully he will reciprocate and treat me like one, too. We are also both in GTMO in a prison; he’s detained, and I’m on orders. Oh, and we both have families. I’m not married and I don’t have kids, but I have a niece, nephews, and cousins, and I am sure he does, too. We probably both like to eat and drink; maybe I’ll find out what he likes to eat and bring it with me to the interrogation as a kind gesture. I started with the basics. We all breathe the same air, eat, drink, and have emotions, feelings, and beliefs, so if I could establish common ground with any of those things, it’s something I could hopefully build on. Even if we didn’t not share the same beliefs, I could still empathize with his and show sincerity. Also detainees were usually inquisitive about who I was and how I got there, so that created an opportunity for conversation and hence establishing rapport. You see, you can build rapport with anyone, even a terrorist. Some of you may be thinking, Why would you want to? Or, How could you? The answers are I had to, and I could because I knew if I were able to build rapport and gain respect and trust, I would be gaining something far more valuable in the end: intelligence information that would keep the United States and its armed forces and civilians safe. That’s why and how I was able to do it. Remember: You can build rapport with anyone.

A Day in the Life of an Interrogator

It’s late in the evening; the air is still hot, humid, and sticky. My sweat-soaked uniform has since dried out and now I have the chills from the air conditioning blowing overhead in the interrogation booth as I wait with my interpreter for “Ahmed” (name changed for security reasons), my Saudi detainee, to arrive. Enthusiasm was nonexistent; in fact, I was disheartened. Every Saudi detainee I had interrogated up until that point seemed completely hardened and intractable. My Saudi detainees would typically sit across from me, their black eyes glaring at me almost as though they were shooting knives into my soul. I knew that they would have stabbed me if they had the chance, but they were chained and handcuffed to the ground, so that wasn’t going to happen. They would scowl and growl at me and say I had the jinn (evil genie) in me. I got nowhere with Saudis. I tried every approach and rapport-building technique possible with these guys. That night I was sure I’d be in for another exhausting interrogation that would ultimately end up being another letdown.

I had worked for hours on my interrogation plan; I ran every possible scenario through my head as to how I could get him engaged in conversation. My head was spinning with ideas. Suddenly a door down the hallway opened, with the familiar shout of “Detainee on deck!” interrupting my concentration. My interpreter and I looked at each other and sighed. He knew it was going to be a long night, too. I started having second thoughts. What if I tried something entirely different? I’ll just go with my gut feeling, I thought. No plans. Just then Ahmed appeared at the door flanked by military guards. He was approximately 5 feet 9 inches tall, his hands were clasped together, his shoulders were rolled inward, and his posture was slumped over slightly. As I observed his body language, I knew this was a significant departure from the typical broad-chested, head-held-high, ready-to-fight stance of my other Saudi detainees. His shoulders curling inward told me he was unsure of himself and the situation, possibly nervous or frightened. I smiled. He lifted his head and his eyes caught mine. For a microsecond I saw him leak a tiny smile that flashed on his face before it went right back to a frown. (This is called a micro-expression, which I will discuss in further detail in Chapter 9.) I knew I was right to go with my gut.

The guards guided him to sit him down in the chair. For the detainees we had metal folding chairs that did not swivel or roll so that the detainees would stay seated securely while chained to the dead-bolt in the ground. We interrogators sat in cloth-covered, swiveling, rolling chairs, obviously much more comfortable. As the guards guided him toward the chair, I said, “Stop!” Ahmed looked at me with concern on his face, and so did the guards. I removed his chair and rolled my comfortable chair in front of the deadbolt. “I would like him to sit in this chair,” I told the guards. Now my interpreter looked concerned, too. Normally I informed my interpreter of everything I was going to do in the booth so he wouldn’t be taken off guard and we could work as a cohesive team. I didn’t tell him I was going to swap chairs and have myself sit on the cold, metal chair, because I hadn’t planned on it. But my gut told me to do it. My interpreter knew I always did things for a reason and was probably initiating my Plan B. Many times I would initiate Plans E, F, G, too! An interrogator has to be as adaptable as water flowing through crevasses to find its way to the solution.

At first Ahmed resisted, he shook his head back and forth saying, “Laa!” which means “no” in Arabic. My interpreter translated: “No, please, I cannot take her chair. Please give me the other chair.” I smiled, and, looking straight in his eyes, I said, “Please sit in my chair; I want you to be comfortable tonight.” After my interpreter translated, Ahmed gave up resisting and reluctantly sat in the chair. The guards bolted his leg and waist chains to the deadbolt in the floor, and then I instructed them to un-cuff his hands. Ahmed now looked at me and smiled back. I thought to myself, Is this the right guy? The guards asked if I needed anything else; I said no and dismissed them. My interpreter and I sat down, bringing our chairs a little closer to Ahmed, into his social space; he didn’t seem to mind. There are four types of relationship space zones: intimate, personal, social, and public. These zones differ from country to country. In many countries in the Middle East, these zones tend to be a lot closer, to the point of being virtually nonexistent. For example, people will stand in your intimate space in public, and men will walk hand-in-hand down the streets together as a sign of respect. But for Americans, the zones are more clearly delineated. Intimate space is typically a 1.5 foot buffer zone around you into which you allow only a spouse/significant other and children. Personal space is approximately a 1.5-foot to 4-foot buffer zone, where you let in only close friends and family. Social space is approximately a 4-foot to 12-foot buffer zone into which you let in acquaintances and coworkers. And public space is anything outside of a 12-foot buffer zone, where the rest of the world exists.

As the saying goes, when in Rome, do what the Romans do. As my interpreter and I leaned in together and were about to engage my detainee in conversation, he started speaking immediately in Arabic. I listened while my interpreter translated: “Thank you so much for the nice chair. I feel badly for taking it, but thank you.” I checked my file, asked him his name and some other questions, and confirmed that in fact I had the right detainee. Fast-forward three months later and Ahmed and I established incredible rapport, which led to a relationship of mutual respect, all created purposefully on my part, of course. We shared tea together and exchanged stories and even some laughter, and I gave him special privileges for his cooperation. He gave more information to me during those three months than I ever could have imagined.

One day he asked me to sneak him into interrogation later that night because he had something secret to tell me. He didn’t want the others seeing him for fear they would think he was cooperating with us (which he was) and retaliate against him. His information ended up being so valuable that it launched a huge investigation inside the camp. He became sought after by other entities because of the cooperation and level of trust and rapport I had built with him. A few days later, after terminating one of our interrogations, I was standing in the doorway waiting for the guards to bring him back to his cell, and he asked me, “Do you want to know why I cooperated with you and told you all of that information over the past few months?” I smiled and said, “Yes, Ahmed, I do.” He replied, “Because you were so nice to me that first day, giving me the comfortable chair, that I had to be nice to you. You respected me and so I had to respect you. It’s my culture.” Had I not listened to my gut feeling, I never would have been able to build that relationship with Ahmed, and, certainly, I never would have gotten the intelligence information I did. All because of a comfortable chair.

Generally speaking, people feel the need to reciprocate acts of kindness, whether it’s a simple smile or helping someone—even detainees in GTMO. This is a common elicitation technique called quid pro quo, Latin for “this for that.” Usually if you share something personal with someone he will share something personal with you; if you offer to buy someone a drink, he will buy one for you in return. You get the idea. It’s simple, and it works.

Getting Anyone to Like You

Wouldn’t you want to know how to get people to want to like you? Of course you would! I will tell you how to accomplish that with 10 specific rapport-building techniques. If you understand that people like people who are similar to them, then this chapter will be your bread and butter for creating long-lasting, meaningful personal and professional relationships that can then lead to increased trust (from a significant other) or even an increase in income (from your boss). After all, it’s not the product that makes a sale; it’s the salesperson who makes the sale through the relationship she builds with the buyer by using rapport and persuasion. I train salespeople and small-business owners on rapport-building skills and enhanced communication skills to make them better at what they do. People do not want to buy things they need from people they don’t like, but people will almost always buy from people they like, even things they don’t need!

Rapport is a feeling, the connection created between two or more people when they are interacting and communicating with each other. It is also behavior, the things people do that help them relate to one another. Rapport is about empathy, respect, trust, acceptance, and sincerity. It’s about connecting on an emotional level. You can show another person that you can identify with her by listening with sincerity, understanding how she views the world, and respecting her views, whatever they may be. This is especially important when interacting with people from other cultures and showing respect for their cultural norms. Ultimately, rapport is a mutual, positive relationship, and when you have it, you have a bond and, thus, a relationship.

You may have read that there is such a thing as both positive and negative rapport-building, and I agree with this. The difference between the two is this: When you build positive rapport with someone, you do so by getting someone to like you by saying or doing things that encourage that person’s respect, admiration, interest, and sincerity. When you build negative rapport, you do it by doing things that could be considered immoral or unethical, such as bribing someone with special incentives or perks, or building common ground at the expense of others (usually by ridiculing others or engaging in condescending or hurtful banter). My advice? Don’t engage in negative rapport-building; it can end up being costly in the end, not to mention the fact that it’s just not nice.

Some authors who have written on this subject contend that rapport is not necessarily about getting someone to like you. I disagree with this. You can’t have a positive relationship with someone you don’t like. Rapport can certainly be used to get people to like you, because remember: People like other people who are similar to them. How do you become similar to other people? By finding or creating common ground with them. Common ground may be that you both like the same football team, or you are both from the same city, or you both have dogs, or you both enjoy sailing. You get the idea. You can build common ground on the largest of topics, too; you both have families, or you both enjoy the art of negotiation. Whatever that common ground is, find it with the person with whom you are trying to build rapport, whether you’re giving a sales pitch, interrogating a prisoner, arresting a criminal, negotiating a divorce settlement, or doing your best to ace a job interview. Establishing common ground is just one rapport technique. I am going to give you 10 more you can use to get people to like you, to want to converse with you, and to admire and trust you. My 10 rapport-building techniques are as follows:

1. Smile.

2. Use touch, carefully.

3. Share something about yourself (quid pro quo).

4. Mirror or match, cautiously.

5. Demonstrate respect.

6. Use open body language.

7. Suspend your ego.

8. Flatter and praise.

9. Take your time and listen.

10. Get the person moving and talking.

Let’s discuss each one in further detail.

1. Smile.

There are two types of smiles: a sincere smile and a sales smile. In a sincere smile, a person smiles with his eyes; you can see crow’s feet, or smile lines, around the eyes. In a fake or sales smile, there are no corresponding smile lines around the eyes. I flash a sales smile for photos purposely so my crow’s feet don’t show! To accompany a sincere smile, try also raising your eyebrows. Raised eyebrows indicate interest. This subconsciously tells the other person you are interested in him or that he should be interested in what you just said. When we look at babies and cute cuddly animals, we are usually wide-eyed and smiling. Why? Seeing how adorable they are generally elates us, and we want them to see us the same way. Dolls and cartoon princesses all have huge eyes so that they are visually pleasing. Therefore, the bigger our eyes are (within reason, of course), the more attractive we are to others. Interestingly, our pupils will also dilate when we see something interesting or attractive. The eyes express so much without words; use yours to your advantage.

So, in order to appear sincere when your boss shows you pictures of her newborn baby (which you really think looks like a constipated, red pickle), offer a sincere smile (remember to crinkle your eyes) and raise your eyebrows as you say, “How adorable!” Smile when you’re on the phone, too. Did you know that you can actually hear someone smiling? Of course it’s a little harder to tell if the smile is sincere, but you can listen for sincerity. You can also hear whether someone has energy and enthusiasm. Smiling will give you charisma. People who smile come across as optimistic; the more confidence you have, the more energy you have; conversely, the less confidence you have, the less energy and charisma you have. People like other people who are positive, upbeat, happy, and optimistic—in a word, charismatic. We tend to trust people with these qualities more than we do people who appear quiet, shy, unhappy, lackadaisical, or boring. It never hurts to smile!

2. Use touch, carefully

When trying to make a good first impression, you need a strong, unforgettable introduction. You want people to remember you by getting them feel good about themselves. The first time we touch people when we meet them is typically through a handshake. Depending on where in the world you are, follow the cultural norms for greeting a stranger (in some countries this could be a bow). In the United States, we like a firm handshake; other countries prefer a softer, gentler handshake. Don’t overdo it by squeezing so tightly you cut off circulation, or shaking so enthusiastically you give the other person a headache. A slightly firm grip while shaking up and down once or twice will suffice. People ask me what a proper handshake is. A proper handshake is always a reciprocal handshake. Always match your handshake to the other person’s. Also, make sure you don’t have sweaty palms. Wipe those mitts dry first, either in your pocket, behind your back, or on the front of your suit jacket, as though you were straightening it. Also, never use the politician’s handshake, the two hands handshake, unless you are shaking hands with an elderly person or want to express sincere sympathy. You should never use the politician handshake for control; it’s an instant rapport killer.

After the handshake, the initial touch, there is the follow-up touch. I know this sounds a bit strange, even provocative, but I assure you it is not. In today’s society, touch seems to be restricted only to those people we know really well, such as family and friends. How your family handled touch when you were growing up, whether you hugged a lot or never showed affection, will have an effect on how you feel about touching others now. Also, with the ever-present spectre of sexual-harassment charges hanging over everything, people tend to err on the side of keeping their hands to themselves. I don’t blame them. But what we may be missing is the important message that touch brings. Touching a stranger respectfully and professionally can bring about a deeper sense of connection and bonding and help you build rapport. Sometimes touch can speak for us when words fail; a hand on the shoulder when someone just told you he had to put his dog down says, “I’m so sorry, I am here for you.” Touching doesn’t just involve other people, of course. We also do what I refer to as self-preening—twirling our hair, keeping our arms close to our sides, hugging ourselves, picking at our cuticles, rubbing our upper lip with one finger, massaging the stress out of our neck, or rubbing our hands up and down our arms. All of these gestures send a soothing, calming message to our brain. How the brain responds to the touch of others depends on the context: who is touching you and in what type of setting.

Using touch when you first meet someone means you will be touching a stranger, so you should know the safe zones. The upper back and the shoulder down to the elbow are typically the safe zones where both genders can touch one another safely. It is never okay to touch the lower back. This is an intimate zone. If you see two of your colleagues together and a male escorts a female through a door while his hand gently touches her lower back, he’s either a real boundary-buster or they are sleeping together. Abiding by the rules of safe zones, try to incorporate touch with someone new at least three times within the first 10–15 minutes of the conversation. Your first touch is the opening handshake. Your second could be a light touch on the back of the shoulder as you introduce Jane to Bob. The third could be a gentle tap on the upper arm, accompanied by a shared joke or laugh. The fourth could be shaking the person’s hand one more time before you depart, as you tell the person how much you enjoyed meeting him. You just touched a stranger, safely, four times.

3. Share something about yourself.

People tend to want to reciprocate confidences and positive behavior, so share something personal about yourself by using the quid pro quo elicitation technique I discussed earlier. For instance, if I confided to you that I was pulled over for speeding last night and got a ticket for $180, I would expect you to come back and share a similar experience. If you responded by saying, “That stinks. I got pulled over last week but was able to get out of the ticket because it was my birthday,” I would know you are comfortable sharing personal information with me. I could then choose to share more secret or sensitive information in hopes that you would reciprocate in kind.

I am often hired as a role player to test students during their training. In one test my goal is to get them to share sensitive information with me. I do this by using the quid pro quo technique. I don’t share real sensitive information with them; I make it up. Their information, however, is legitimate. If I can get them to think that I trust them enough to open up and confide in them, they usually dive in and share their own secrets with me. Essentially I am exploiting the fact that people are generally trusting of trusting people, but because it’s training, I have to do it in this particular circumstance.

Using quid pro quo can help you uncover common ground. Going back to the previous example, let’s say you shared with me that you were pulled over, too, so maybe our common ground is that we both like to drive fast, or we both think the speed limit should be raised, or we both believe that cops have nothing better to do than to hand out tickets. Of course, you can find common ground with people without even trying. I usually like to sleep on a plane. However, if I hear my neighbor speaking in the same accent as mine (which is rare, because not many people “speak” Rhode Island), I instantly feel we have a connection or share a commonality, so I am more likely to strike up a conversation with that person. I have seen strangers pass each other while walking on the speed walkways in airports and giving each other high-fives in the air or nods of approval because they are both wearing the same sports team jersey. Similarly, my dad is a Harley guy, and when we go out riding together, anyone we pass who is also on a motorcycle, even if it’s not a Harley-Davidson, waves because we are part of the same club that likes motorcycles. See how easy it is to find common ground? Once you both say “Me too!” or “I totally agree with you!” you are connected emotionally through rapport. Let the negotiating or pitching begin!

Here’s another example. You’re in long line of people at the grocery store, waiting to check out, and you can see the cashier is frustrated and taking it out on customers. By the time you get up to her, she’s in an even worse mood than she was before. You haven’t done anything but patiently wait in that line, so why should you be treated with disrespect just because she’s having a bad day? You shouldn’t. So next time, change her attitude by using this technique. Trust me, it works! I used it myself once when I was in a line that extended halfway down an aisle, it was so long. I could see the cashier was already frustrated about trying to check people out as fast as she could, and I knew that when she saw my basket of stuff, it would only increase her agitation. One by one, all the customers in front of me started mirroring her attitude. When it was my turn, I decided to change her attitude instead. I walked up to her, gave her a big smile, put my basket on the counter, and said, “And to think I came in for two things. Ugh!” She paused, looked up at me, relaxed her shoulders, smiled, and said with a sigh, “You are just like me! I do that all the time.” I built common ground with her, but it was my smile that really broke through her unhappy disposition. I don’t think any other person in that line smiled at her. Quid pro quo, people! You get back what you give.

4. Mirror or match, cautiously.

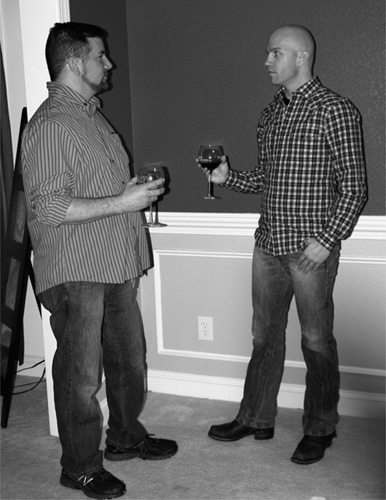

Rapport can be established by mirroring a person’s body language, vocal tone and pitch, words and phrases, rate and speed of blinking, and even breathing. Mirroring body language (isopraxism, if you want the fancy term) involves displaying the same posture and movements as the person you are with, but in a mirror image. In the following image, Kelly (right) is holding a wine glass in his left hand, while Chris (left) is holding his glass in his right hand. They are a perfect mirror image of each other. Let’s say you are at a job interview, and the interviewer is sitting behind a desk. At one point she leans in and rests her left elbow on the desk, with her hand under her chin. If you wanted to mirror her, you would cross your left leg over your right knee, lean in, rest your right elbow on the top of your knee, and touch your fingers to your chin.

Mirroring.

Matching body language is the inverse of mirroring; it occurs when you display the exact same body posture, but without the mirror image. In the following image, Kelly and Chris are matching each other by holding their wine glass in their right hand. Going back to the previous example, if the interviewer were resting her chin on her right hand, you would rest your chin on your right hand, and so on.

Both mirroring and matching require the conscious study of another person’s behavior, but they need to occur outside the conscious awareness of the other person so that they appear natural and unconscious on your part. It’s important you don’t mimic the other person, as that will only destroy rapport. To this end, avoid making sudden movements, and wait 30 seconds until you start matching/mirroring the other person’s movements or speech. As well, put your own spin on your responses and vary them so that they are slightly different from the other person’s. The second someone catches on to what you are doing is the second you look like an idiot. If you’ve ever caught someone copying you, it was probably annoying and a little creepy, right? But if you can subtly match your movements and speech to those of others, subconsciously they will think you are similar to them and, thus, feel they can build a connection more easily. It’s almost as though you were creating common ground simply by looking and sounding like the other person.

Matching.

When the other person starts to mirror or match you unconsciously in return, this is called pacing and leading. Try it out today at work or tonight at home. See if you can get your coworker or family member to start mirroring or matching your posture and gestures. When he or she does, he or she is fully in tune with you and probably hanging on your every word. You can mirror and match people over the phone, too—just use the same words, speech patterns, vocabulary, tone, pitch, and volume. If you talk and sound like them, they will like you without even knowing it and—voilà!—you have rapport. I often use this technique when I have to call the technology help desk. Because I am technologically challenged, I know I am going to frustrate the person on the other end of the line, so I start building rapport as soon as I can. I can usually hear the other person smiling over the phone by the time we hang up.

If you ever have to work with an interpreter, match and mirror the person you are talking to, even though you cannot understand each other’s language. Do not let the interpreter do the matching or mirroring because then your interpreter will be the one building rapport! Good interrogators train their interpreters to match or mirror their body language so that they work and act as one. Even though the detainee only understands the interpreter, rapport is (hopefully) established with the interrogator since the interrogator is the one setting the pace.

I often find that mirroring verbally is easier and more effective than mirroring the body. If I mirror someone’s tone and pitch of voice, and rate and pattern of speech, versus mirroring posture and gestures, I sound like that person, and hence they think I am similar to them. For instance, Introverts tend to speak softly and slowly and think about what to say and how to say it for fear of putting their foot in their mouth. As an Extravert, I tend to speak loudly and quickly, and quite often I put my foot in my mouth. So when I converse with more introverted people I have to tone it down so I am more like them. (I will speak more on personality preferences in Chapter 7.)

An example of how I use words to mirror is my blond witch story. I was grocery shopping one day and wandered up to the wine tasting table. The gentleman behind the table handed me a tasting cup and just before I could take it, he pulled it back. “Do you have ID?” he demanded in a condescending voice. I thought, Wow, what a compliment! I handed him my license that had a picture of me circa 2002 with dark hair, the color I was born with. “You had dark hair,” he sneered. Nothing like stating the obvious, I thought. Not happy with his attitude, I decided to use my rapport-building skills to get him to act a bit friendlier toward me. “Yeah, I use this thing called bleach,” I replied with a big smile.

He handed my license back to me and began pouring the wine. “I call it witchcraft,” he said.

“Well, witchcraft costs a lot of money,” I jokingly replied.

He looked up and smiled. Success! At that point another female shopper with blond hair joined our conversation. “I use witchcraft, too, and it’s draining my wallet,” she said as she leaned in and pretended to whisper confidentially to me. Both of us used his word (witchcraft) and it made him feel good. Soon the three of us were chatting away as we tasted the wine. I bought a bottle and left happy. There is power in using other people’s words. People will pick up on the fact that you are doing it, and it makes them feel that you are paying attention to them. And let’s face it: who doesn’t want attention?

5. Demonstrate respect.

What comes around goes around. Karma is a bitch. What you dish out, you get back. All of these sayings basically say that how we treat others is how we’ll be treated in return. If you aren’t going to give it, you aren’t going to get it; it’s that simple. So how do you show respect so you can get respect? First, allow people to have their own views and opinions, just as you would want others to allow you to have yours. Sometimes you have to agree to disagree, which requires ego suspension. Be courteous, polite, professional, and non-confrontational. Show esteem, admiration, and honor toward each and every person. As I would always tell my students who were training to be interrogators, you attract more bees with honey than with vinegar. In other words, you’ll get more from people if you are nice. Who wants to give anything, whether it’s a discount, a freebee, advice, or sensitive information, to a mean person?

I tried to instill in new interrogators that no matter what heinous crime a detainee committed—and believe me, many were beyond heinous—they were still human beings and should be treated as such. The inexperienced interrogators I worked with always reverted to saying something along the lines of “Tell me the truth, or else!” Or else what? Or else they stay in prison? Or they won’t get a cigarette? Detainees would refuse to cooperate if they heard that. They became defensive, confrontational, and even aggressive. It only makes sense. It’s like a parent yelling at a child, “Clean your room, or else!” That approach isn’t typically effective because it just makes the child defiant. These detainees didn’t care because they knew we couldn’t and wouldn’t make them talk. The only choice we had was to get them to want to talk. We didn’t have to ask “pretty please,” but we did need to show some respect while still being the authority figure. When I showed my detainees respect, most of them respected me in return, and that is how I built rapport and obtained intelligence information. So the next time you are in a restaurant and the waitress brings you the wrong order, instead of griping at her and calling her incompetent, try politely saying, “I’m so sorry, but this is the wrong order. Would you mind bringing me what I ordered so I can eat with my family? Thank you so much.” She’ll probably hustle to go find your order instead of spit in your food.

The other advantage to being respected is that you also gain trust. When you get someone to trust you, you will be allowed into his or her personal space. We let our guards down with people we trust and tell them our fears, desires, and secrets.

6. Use open body language.

If you want people to open up to you, you first have to open your body language. If you close up your body language, people will close themselves off to you. To keep your body language open, expose the three vulnerable zones that I mentioned earlier: the neck dimple, the belly, and the groin area. When all three vulnerable zones are open and exposed, you are unconsciously saying, I trust you not to hurt me; I trust that you won’t hit me in the neck dimple and collapse my trachea, or punch me in the belly, or kick me in the groin. By the way, if you have never been hit in the stomach, be thankful. I used to practice Shorin Ryu Karate more than a decade ago. I was a brown belt and in the best shape of my life. In one drill I was up against a 16-year-old black belt named Manni who was a powerful fighter. I had to block his punches, but needless to say I didn’t block the first one; he hit me in the stomach and knocked the wind out of me. It was the first time I had ever gotten the wind knocked out of me and I thought I was going to die. I literally could not breathe. When my breath finally came back, Manni said, “Now you’ll block my punch,” and I sure did! Speaking from experience, the stomach is a very vulnerable zone. Exposing this and the other vulnerable spots tells people you are confident and open to them. It silently broadcasts that you trust them, and hopefully they will trust you, too.

Try not to cross your arms in front of your chest. People almost always take this gesture as defensive or rejecting, and most of the time it is. Not always; sometimes people will do this when they are thinking or just cold. But most people will see it as defensive, so don’t do it). Also, keep your palms open and exposed; don’t face your palms inward toward your body or, worse, hide your hands by stuffing them in your pockets. Finally, don’t close yourself off by putting up barriers between you and the other person. A barrier can be a desk, a computer screen, a pile of papers, or even a glass of wine. Your body can be used as a barrier, too. For instance, if a man approaches a woman seated at a bar and she has no interest in him, she will look over her shoulder, with her arm remaining between them, to politely refuse his advance. Her arm and shoulder are her barriers. She may even prop up her purse for reinforcement.

Remove all barriers between you and the person with whom you are trying to build rapport, because a barrier will block communication. When I was interrogating detainees, I would usually keep the table off to the side so I could take notes; or, I would just take notes with my notepad on my lap. I removed all barriers that I could between the detainees and myself. I wanted to open myself up as much as possible to win their trust and, ultimately, form an emotional bond with them, which would then elicit shame if they were to lie to me.

7. Suspend your ego.

Sometimes you have to be open to advice, education, and criticism in order to build rapport. People who have inflated egos have a hard time being corrected, criticized (not degrading criticism, but constructive criticism), taught, or advised. So for example, you will need to learn to suspend your ego and your pride when a potential new client wants to teach you the importance of branding for her company, even though you are a marketing director. I had to do this many, many times, and I still do it to this day, because I have a security clearance and can’t talk about what I do anyway. The upside is that I let people feel good about educating me. People with security clearances can’t disclose details about their jobs, especially to people who don’t have a security clearance. If a bunch of people without clearances are trying to one-up each other by sharing stories about the projects they are working on, people with clearances can’t join in and share anything about what they are working on. Navy Special Forces are in the same boat; when they are around other sailors, even in the intelligence community, they can’t share any information about what they do, where they have deployed, or what missions they’ve gone on. This used to be especially hard for me when I heard people talk about all the torture and abuse that allegedly happened in GTMO. I was there, and I didn’t witness any type of torture or abuse (physical or mental) of detainees, but unfortunately I had to bite my tongue while they vented their ignorance, because they didn’t have a “need to know.”

8. Flatter and praise.

Flattery, when done artfully, makes people feel good. When people feel good they want to share more about themselves to make you realize just how great they really are. Just don’t overdo it. If you lay the flattery on thick, people will see right through you, and you will lose all credibility and rapport. You can flatter people on their physical appearance if it’s socially acceptable. If a coworker loses 30 pounds, for example, it’s okay to say, “You look great and you must feel so healthy.” When flattering the opposite sex, however, it’s always safer to flatter about nonphysical attributes such as the other person’s work ethic, dedication, assistance in a new project, role as a mentor, subject-matter expertise, and so on. If you’re a man, avoid saying to a woman, “Wow, you look great in that dress.” I would flatter my detainees by telling them I knew how proud they were of their culture, religion, and family, or that the other detainees looked up to them as role models. The trick to flattering or giving praise is being genuine and sincere; the rule is that a little goes a long way.

9. Take your time and listen.

Nodding your head up and down in the affirmative tells someone, “Keep talking. I’m listening and I’m interested.” It also says “I agree with you,” “I like what you are saying,” or “I want to hear more.” Add an eyebrow raise and it augments the message of interest. If you see someone nod at you like this as she flashes a sales smile, be leery—she’s probably just appeasing you as she’s figuring out a way to escape the conversation. Be sure to listen to people. Don’t cut them off, jump the gun and answer a question before they are finished asking it, or finish their sentences for them. All of these habits are annoying and send the signal that you would rather hear yourself talk. When you show people you are interested in what they have to say, they will appreciate it, and it will make them feel important. Learn to slow down and take the time to really hear what they are saying. If you aren’t listening, you’ll miss critical information.

During my interrogations, I would get so anxious to ask the next question that I would often forget to pause to see whether the detainee would freely add more information without my having to ask a follow-up question. Pausing is actually a great technique because it creates silence. Most people find silence awkward and uncomfortable, so they will quickly pick up the conversation again just to alleviate the awkwardness. I tell people to enjoy the silence. If you create a space for silence and let others do most of the talking, two things happen: First, they will give you information; second, their ego will get a boost, because it exploits the fact that people love to be heard and hear themselves talk. This makes them feel good, and you know what happens when we make people feel good: They are more apt to like us. Because my job was to get information, I often sat back and let the detainees carry the conversation; after all, when I was talking, they weren’t.

10. Get them talking and moving.

This is the last rapport-building technique because by this point in the conversation, you should have already established some rapport; now you just want to strengthen it. We already know that letting people talk is a good thing. Now you really want to get them to warm up to you to stay engaged in the conversation. You do that by asking open-ended questions that require a narrative response, versus yes-or-no questions. Another good way to do this is to ask for help. For example, say you are on a plane and you ask a stranger to help you open the overhead compartment to put your bag in; or you are in a crowded bar, and instead of squeezing between patrons to order a drink, you ask a person sitting at the bar to order one for you. When you ask people for a favor, and they do it, they end up feeling good about themselves for helping. I used to work with a retired FBI agent who was a behavioral analysis expert. He would often say that no one helps others just to be kind; they do it to make themselves feel good. I don’t disagree with this in theory, but are we really that selfish? I think there is definitely an element of wanting to feel good in any act of altruism. Jody Arias did this with reporters while in jail. She proved to be very cunning and often used her looks to deceive people. She knew the trick of getting people to do something for her so that she could build rapport. While in jail preparing to be interviewed by reporters in 2008, she engaged reporters in non-pertinent, friendly chit-chat, and then asked them to bring her a compact so she could “freshen up her makeup.” She even said, “Don’t roll the cameras yet.” Jodi was trying to get everyone on her side and to think of her as the pretty, innocent victim. Remember: To sell yourself, a product, or an idea, the first step is to get people to talk to you.

Asking for favors and asking open-ended questions will help keep your target engaged. Now let’s get him moving. If you have the opportunity, move around as you are talking to someone. It can give the impression that you have spent hours together in many different locales when in reality, you have only spent a few minutes in each other’s presence. Walking and moving around will also relieve stress. If you are an attorney who is about to interview a new witness, try to start the conversation as soon as you meet him in the lobby; then continue to talk with him as you make your way to the actual meeting place. If you take a break, have both of you walk to the coffee shop or concession stand and back to the meeting area. When you close the meeting, walk the witness out. The witness will feel as though he has spent an entire day with you and feel more closely connected to you.

All in the Family

It is really difficult for me to use my skills on my friends and family, but sometimes I have to. When my colleague Serge and I were forming our company, he actually came up with the name and symbol (and I’m usually the artsy, creative one). I loved it instantly. I developed our brochure with the new name and logo and sent a copy to my brother, who designed our Website. He printed out our brochure and walked it over to my parents. I got a phone call from my mom as I was battling Virginia Beach rush hour traffic: “Dad wants to talk to you.” Oh god, here it comes, I thought, because my dad made her call me for a reason.

“Yeah, Dad.”

“I don’t understand this congruency name. [My company’s name is The Congriency Group.] I don’t like it. What does it mean? You know a name of company is everything. Steve Jobs had a hard time getting Apple to take off because of its name. The average Joe isn’t going to know what congruency means. I don’t know…you’d better re-think it.”

As I tried to explain the meaning of the name and why we choose it, I felt myself slipping back to my typical way of conversing with my dad: on the defensive! I am just like him (stubborn). When we get something in our heads, it is going to take moving the moon to convince us otherwise. As the conversation went on I realized I was arguing with him. I thought, What do I do for a living? I teach people how to diffuse arguments! Why can’t I do this with my dad? So I flipped on the switch and started using my techniques, using word repetition (I will talk about how to repeat words to diffuse an argument in a moment), asking him to offer an explanation (because I certainly wasn’t changing the name!), and flattery. I asked him what he thought I should do, and he responded that I had to explain the name somehow. I responded by suggesting we put the history of the company’s name on the brochure and Website. Ultimately we agreed. I left that conversation making him feel good for his suggestion. In hindsight, it was a good suggestion, and you will see the explanation of my company’s name on both our Website and brochure. But the reason I told you that story was to prove that I had to swallow my ego and listen to his constructive criticism, as well as be patient and listen attentively in order to have a mutually respectful conversation. I changed the fate of that conversation for the better. When you realize you have fallen into the trap of arguing with someone or getting frustrated trying to prove a point or explain something, stop and take a breath, and employ your new rapport-building techniques! Suspend your ego, use flattery, be respectful, mirror/march that person, listen attentively, repeat words that other person uses, and smile. Here is another example of these techniques in action:

Son: “It’s not fair that you took my PlayStation away!”

Mom: “So you don’t think it’s fair that I took your PlayStation away?”

Son: “Yeah! My friend’s mom never takes his stuff away!”

Mom: “Your friend’s mom never takes his stuff away, huh?”

Son: “No! You are not fair!”

Mom: “So, to clarify, I’m not being fair to you by taking away your PlayStation because you don’t do your homework. Am I right?”

Son: “I do my homework, Mom!”

Mom: “Hmm, you do your homework, but I got a note from the school saying you haven’t.”

Son: “I did do it; I just forgot to turn it in.”

Mom: “So because you forgot to turn it in, I am unfair. Is that right?”

Son: “Okay, okay, I’ll make sure to turn it in tomorrow.”

Mom: “Good! Turn in your homework on time and I’ll be fair with you.”

So instead of the son storming off to his room, slamming the door, and ignoring her for the rest of the evening, the mom calmed him down through the art of conversation and word repetition. Trust me, it is as easy as this, and I use it all the time with family and colleagues. (I realize, of course, that if they read this book, my secret is out!)

Mirroring, which I’ve already discussed, is another great technique to use when trying to diffuse an argument. If you incorporate pauses and slow your rate of speech when you’re engaged in a heated discussion, you are not backing down; in fact, you are gaining the upper hand. Because people who speak more slowly and with a lower-pitched voice seem more confident and calm, the aggressor will soon feel foolish raising his voice or getting emotional. Your goal is to get the aggressor to pace and lead you, especially your demeanor, in order to calm everyone down and have a rational conversation.

Five Tips for Enhanced Communication Skills

Building rapport will enhance your interpersonal communication skills, I promise you. But I want to share some other tools that will help you communicate effectively and build respectful, reciprocal relationships, both personal and professional. Here are five tips to add to your arsenal of enhanced communication skills.

1. Manage your emotions.

If you take things personally, you will be emotional and irrational. Realize that sometimes you are talking to the role/title/position, not the person. And the position, not the person filling it, may tell you that you are not meeting expectations. You can’t dislike someone or get mad at someone who is doing her job, even if she could use a little more finesse doing it. Try not to feel personally attacked when people offer you constructive criticism or advice on how you could do things better. Likewise, if you can’t handle the truth, don’t ask for advice. Don’t be offended when people stand up for what they believe and it’s the opposite of what you believe. We are all entitled to our opinions. And don’t take it personally when someone disagrees with you. Never feel that you have to defend yourself; just provide the facts with a calm demeanor (as I am still learning to do with my dad).

2. Agree to disagree.

If you expect people to always like you or agree with you, you are setting yourself up for disappointment. You have to accept that you cannot change people. The idea that we can change others is a major cause in relationship struggles. If one half of the partnership thinks that, over time, he or she can change their partner, let me just be blunt with you and say: Give it up, it’s not going to happen. We are all guilty of this to some degree. I was in a relationship with a great guy but he was an introvert and I kept expecting him to change to meet my extraversion preferences; of course, it didn’t happen. I wanted it to work because he was trustworthy and honest, but I realized I couldn’t, and shouldn’t, want to change him, and ultimately, the relationship ended. So if you think, I’ll get him to like wine and the theater eventually, or She’ll learn to love to cook, or He’ll become more open with his feelings and communicate better, or She’ll have more ambition after she realizes her potential, you’re in for a huge disappointment. Don’t expect people to like you, either, even though admittedly it can be a huge blow to our ego when we realize we aren’t liked. And finally, don’t expect people to agree with you all the time. Sometimes you will just have to agree to disagree and move on. If done with mutual respect, you may be pleasantly surprised that the other person respects you for standing by your beliefs, and may come around and see it your way. I have noticed that when I am engaged in a conversation with another person and we both agree to disagree, what we were disagreeing about in the first place assumes less importance in the greater scheme of things. The next time you find yourself trying to tell people what or how to think, say this instead: “Wouldn’t you agree?” If they don’t, that’s okay.

3. Be aware.

Inattentional blindness, assumptions, and biases can negatively affect your rapport with others. The term inattentional blindness means that we don’t see what we don’t expect to see. It can also mean we don’t hear what we don’t expect to hear, and we don’t experience what we don’t expect to experience. Some of you have probably seen that awareness test video on YouTube with the dancing gorilla or moonwalking bear walking through a crowd of people passing a ball. In the video, half of the people are dressed in white clothes the other half in black clothes. The video asks you to count how many times the team in white passes a ball. But while you are busy counting, a dancing gorilla or moonwalking bear walks right through the middle of the people throwing a ball around. When I play this test for people, very few see the gorilla or bear. Why? Once I replay it, they see the animal as clear as day and are usually shocked they didn’t see it the first time around. The reason is because they didn’t expect to see a gorilla or a bear; they were too busy counting how many times the team in white passed the ball. Why is overcoming inattentional blindness is so important? Let me give you an example of how intattentional blindness almost cost me an interrogation, and another example of how an assumption made me look stupid (and made me really mad at myself in the process!).

My first story takes place in an interrogation booth. I was interrogating a detainee, and although he wasn’t confrontational, he wasn’t friendly, either. I had not broken through to him, so we had no rapport. I was trying to engage him in conversation and make eye contact, but he would look at the floor while he gave vague, one-or-two-word answers. He was completely tuning me out and I was getting frustrated. I knew I couldn’t force him to talk to me or like me. At that point my interpreter turned to me and whispered in my ear, “You know he’s praying, right? That’s why he’s tuning you out.” I didn’t know he was praying. I looked over at him and he was lightly tapping his fingertips together mimicking the motion of counting prayer beads. A-ha! I didn’t expect to see him praying so I didn’t see him praying. My inattentional blindness made me so focused on trying to build rapport and gain eye contact I never saw what his hands were doing. So I gently leaned over and put my hand on his hands and asked very politely if he could stop praying while we talked and told him I would give him time to pray at the end of the interrogation, alone in the room. There is a cultural reason as to why I touched him. As a female I was considered “unclean,” and he could only pray if he was clean. So I knew that by touching him, he couldn’t go back to praying. I could have lost rapport with him, but it was worth the risk. He did get upset with me initially, but I was able to regain his trust, especially when I let him pray alone properly at the end of the interrogation, as I said I would. Had my interpreter not told me he was praying, my inattentional blindness might have caused me to end that interrogation prematurely out of frustration and not collect any information that day.

My second story has to do with reading body language. The husband of a friend used to study NLP. Knowing what I do, he told me one day, “I want to do an exercise with you. I am going to say three things. One will be a lie. Tell me what the lie is.” I thought, Oh, fun! He said, “I speak Icelandic, I studied jujitsu, and when I was 11 I won the state national chess championship.” Right away my gut instinctively told me that he was lying about the chess, because not only did he give more details about that than the other two statements, but he also rose up on his toes, leaned in to me, and shrugged his shoulders as he said it. Four clusters of deceptive tells right there! Then I said, “You don’t speak Icelandic.” Why? Because I assumed there was no way he could have. See how an assumption can affect your thinking? I knew he lied about playing chess, but because I let my assumption get the best of me, I missed the real lie. I was so mad at myself. I usually don’t assume anything, a golden rule when you are an interrogator, but that day, I fell victim to it. Shame on me!

4. Favorably influence people.

We want to influence people in a positive way. We want them to like us, trust us, respect us, and feel comfortable around us. Here are three ways you can favorably influence others, what I call the three Es:

• Energize: Have a positive, upbeat attitude. People want to be around those who are positive; no one wants to be around a Debbie downer or an energy zapper. Positive energy is infectious. I was once told I have an infectious smile; it was the nicest compliment because it meant that I could to make others smile.

• Encourage: Be sincere and empathic toward others to encourage them open up and share their feelings, thoughts, and ideas. The best leaders are those who make their subordinates feel that they can voice their concerns and views without any repercussions. People look to other people for confirmation, and trust people with authority. To be regarded as someone with authority, strive to be a respected leader.

• Engage: Don’t rush rapport or conversation. Responding too quickly in a conversation says that you weren’t listening to what the other person just said; you were thinking about what you were going to say. Even if you heard that person, it sends the signal you didn’t listen. It also gives the impression to others that what you have to share has more importance. Engaging is always a two-way street.

5. Don’t be afraid to let them teach you.

This last tip requires ego suspension and works great on people with big egos. There are two elicitation techniques that you can use to get people to teach you: One is by pretending to be naïve (I call it playing stupid), and the other is expressing disbelief (even if fabricated). For example, when I was interrogating I would play stupid to the fact that I didn’t know certain things about my detainees, such as whom they were affiliated with, where they got their training, who they knew in the prison, and so on. I used this technique to get information, and it worked, especially on those detainees with big egos, because they liked feeling that they were smarter than I was or knew more than I did. I put them in a position where they felt I had no clue and that they could do me a favor by teaching me. You can bet I was a good student!

Likewise, when you express disbelief—”I can’t believe you increased your sales that much in just six months”—people will tend to want to explain how awesome they are and how they did it. Both of these techniques allow the other person to get up on their soapbox and be heard.

You now have 10 rapport-building techniques and five tips you can use to enhance your interpersonal communication skills. You are well on your way to being a communication expert! The next chapter will take rapport-building to another level as I talk about personality preferences and how changing yours to match those of others can make or break your ability to get to the truth.