6. Digital Disruption

Digital technology has created gigantic shifts throughout the business world. The full impact has yet to be seen, as it is still morphing—by the minute. In this chapter, we start our discussion of the challenges rattling the entertainment ecosystem by examining the impact on film, broadcast, and cable television. Although the disruption is not limited to these platforms—as you will clearly see in the following chapters—much of the new technology is taking aim at these major content providers, warranting this singular discussion.

Cable Levels Off: The Era of New Challenges

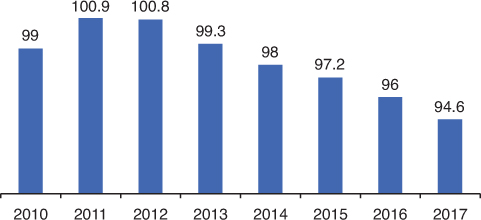

The changes wrought by digital technology have been especially vexing for all forms of television. Even with all of the marketing strategies discussed at the end of the last chapter, cable television subscriptions have dropped off, starting in 2012. Though there are those who say that this is primarily related to the economic downturn and cautious recessionary spending, there is also data that points to an ever-increasing number of people who are either “cord cutting” or, as mentioned earlier in the book, “cord nevering.”

Exhibit 6-1 gives a visual representation of how this fall-off may occur.

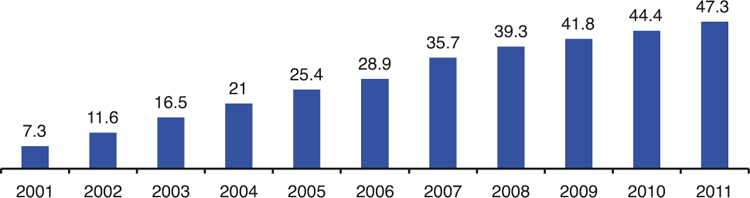

Although the current cable business model still has television—as opposed to Internet or telephony—as the top consumer buy from cable companies, Internet access is quickly moving toward the top of the charts. As of early 2013, more than 81% percent of households have access to broadband Internet.1 But the rising tide of Internet growth might have a huge impact on the current cable business model in the coming years. If certain shifts in viewing continue to happen, multiple system operators (MSOs) could be sowing the seeds of their own demise—though said demise won’t be happening in the in the next five minutes.

1 Nielsen, Cross Platform Report Q3 2011.

Exhibit 6-2 demonstrates the explosive growth of the broadband buy over the last ten years.

The cable companies that provide Internet service to their subscribers should erect a monument to whomever created that strategy, for if cord-cutting becomes the norm, that Internet attachment could be the saving grace of the business.

The Government Steps In

This growth of broadband access has not gone unnoticed at the highest levels in Washington. President Barack Obama, in signing an executive order that would allow for faster and more inexpensive construction of broadband pathways through properties controlled and managed by the Federal Government, stated:

Building a nationwide broadband network will strengthen our economy and put more Americans back to work. By connecting every corner of our country to the digital age, we can help our businesses become more competitive, our students become more informed, and our citizens become more engaged.2

2 “We Can’t Wait: President Obama Signs Executive Order to Make Broadband Construction Faster and Cheaper,” The White House, Office of the Press Secretary.

We might also add, create a wider audience for the products and services we discuss in this book.

Government influence had already entered the scene in 2011. Following the $13.75 billion takeover of NBCUniversal by Comcast, the country’s largest Internet and cable provider, Comcast began a program called Internet Essentials in Chicago. The program is focused on underprivileged families, giving them access to the Internet for $10 per month. This was not entirely altruistic; the FCC had made access for the poor one of the requirements for approval of the deal.

The program offers slow access—3 Mbps, nothing that will allow for speedy download of the latest HD movie—but it does address an interesting issue facing the future growth of full-price Internet subscriptions: saturation in higher income households. Access in poorer households is one of the few growth areas left to providers. And in the classic camel’s-nose-under-the-tent strategy, a little access may lead to a lot later.

There are some who view access to the Internet as a “natural monopoly,”3 one that stands in the way of equal opportunity, one that demands government subsidization. In September of 2012, the FCC helped set up Connect2Compete, which gathers pledges from broadband providers and software companies, all directed at getting computers and access into the hands of the underserved.

3 “Mixed Response to Comcast Expanding Net Access,” The New York Times, January 21, 2013.

The Consumer Steps Out

Cable television’s business model is firmly based in the ability to deliver niche programming, which gives marketing professionals a clear entrée to the homes of the viewers they would most like to reach in a wide range of demographic slices.

But what if you, the consumer, didn’t need cable to watch the content provided by cable channels and networks? Didn’t need to have that set-top box winking at you? Could decide what and when you watched?

Well, you can. And that’s what’s giving the cable industry the chills.

Cutting the Cord

Up until now, the challenge with wirelessly connecting mobile-downloaded entertainment and your television has been the inability to “throw” huge chunks of data without the use of either fiber optic or HDMI cables. Therefore, even though we might have movies on the small screen, the attempt to link them to the big screen leads to fits and starts in picture and sound, fracturing the experience. But as we keep saying, technology is changing by the minute, and as of January of 2013, a breakthrough occurred in image compression that will eventually—within two years, if not sooner—allow all that data to be compressed in such a manner that fracturing will become a thing of the past. The only thing between your mobile device and your television will be a wireless connection, and the only thing coming from your TV will be seamless picture and sound.

Just like cable now delivers to you—but with no subscription fee.

“Ah!” you say, “but you’ll still pay a fee for the content you’re downloading to the mobile device, won’t you?” Of course; this is still America, after all. Land of the free, home of the business. What will become possible is a choice that many cable subscribers are already clamoring for: the ability to pick and choose their content without paying for a whole package.

A La Carte

As cable menus grew—in advertising-supported, public, and premium channels—cable subscriptions began to change. Customers could originally pay for basic cable plus individual premiums—say, just HBO or Showtime—creating a package that suited their own viewing desires. But the cable companies changed the game to create a more complex menu. Current subscribers now must pay for packages that may contain literally hundreds of channels they don’t want in order to get one or two that they do wish to tune in to.

Cable operators claim they must do this in order to pay for the stations that don’t have as many viewers (but create better packages for the operator to sell to advertisers, reaching all those niches we spoke of in the last chapter). Because of carriage fees, the cable provider’s cost of content offerings does vary. HBO costs Comcast more to carry than, say, the Iguana Channel. Cable providers argue that if they were to offer a la carte pricing, allowing subscribers to simply put together their own list of channels, the operator’s ability to average the cost of all these offerings into reasonable subscription fees would be severely limited. There wouldn’t be enough subscribers to HBO and Showtime to spread the carriage cost over all subscribers. Prices would shoot through the roof.

Or so say the operators.

But this inability—or perhaps, plain stubbornness—to provide more flexible subscription plans could actually push the disruption of the cable business model over the edge sooner than later. Economics work in all directions, and it is feasible that enough potential subscribers, simply unable or unwilling to shell out, could eventually walk away. The cable companies would be left with pretty shaky ground under their feet. The golden goose could eventually wind up cooked.

Throughout this book, you have heard us say that content is king—that people will find a way to pay for the content they want to watch, listen to, or read. As long as the content is good enough to appeal to enough consumers and can be limited to as few access points as possible, the market stays steady.

But as Harold L. Vogel so succinctly points out in his book, Entertainment Industry Economics, the Internet is fundamentally changing and transforming many industries—not the least of which is entertainment—and certainly cable.

Vogel states that the Internet

![]() Redefines and rearranges (but does not wholly eliminate) the functions of the middleman or wholesale distributor.

Redefines and rearranges (but does not wholly eliminate) the functions of the middleman or wholesale distributor.

![]() Changes the nature of customer relationships by altering the proportion of total revenue derived by advertising, subscriptions, and sales.

Changes the nature of customer relationships by altering the proportion of total revenue derived by advertising, subscriptions, and sales.

![]() Increases the amount, variety, and accessibility of entertainment program content and related products and services.

Increases the amount, variety, and accessibility of entertainment program content and related products and services.

![]() Opens the way for new forms of entertainment products and services to be developed.4

Opens the way for new forms of entertainment products and services to be developed.4

4 Vogel, Harold L., Entertainment Industry Economics, 8th Edition, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

This, then, is the crux of our discussion. How are the delivery systems changing? Where is the content coming from? And when do we hit the tipping point? This is a $150 billion industry. We’re talking a significant disruption in the world of entertainment marketing.

Like the technology that drives this disruption, this is a highly complex transformation that is taking place. It is impossible to provide every last detail in this discussion with the speed at which things are changing. As before, we urge you to stay on top of this seismic shift. It is critical to your career in entertainment marketing.

That being said, let’s at least start the conversation.

Over the Top

In discussing cable’s challenges, the best place to start is with what is commonly referred to as over the top (OTT)—meaning without the use of the set-top box that delivers cable programming to your television. OTT means, as long as you have access to the Internet, you can stream content directly to whatever viewing device you choose to use: television, tablet, laptop, smartphone—or whatever new device might come along.

This provides opportunities for both the consumer and the providers. While consumers have more freedom to find much of the content they desire, content providers benefit through both transactional- (you pay only for the one-time content you want) and subscription-based (you pay a monthly fee) models.

But some of this creates odd gray areas. Case in point, HBO GO. HBO did a very smart thing when it began expanding its content offering: It made a decision to be its own production house. HBO owns its original programming, which gives it the ability to reuse it as it sees fit without having to worry about working any deals with any outside production houses, as we discussed earlier in Chapter 4, “The Business of Broadcasting: Network TV, Syndication, and Radio.”

In 2012, HBO launched HBO GO, which allows subscribers to the premium service to access HBO’s original programming on all devices, anywhere in the U.S. It’s a great service for HBO subscribers, but what impact does it have on the cable companies?

Consider this: A Comcast customer in Florida subscribes to HBO. But that customer may be a “snowbird,” someone who has a home up north for the hot summer months. Instead of paying Time Warner Cable or Cablevision a fee to watch HBO in New York, the customer simply accesses it through HBO GO. Have these other cable companies lost access to a possible customer?

And while we’re on the subject of this very popular premium service, why doesn’t HBO simply offer its content for a fee separate and apart from cable companies? Does it need the cable cord any longer? It’s an interesting question, given, as we said in the last chapter, that Time Warner Cable and Time Warner have been two separate companies since 2009.

Here’s the thing: For the time being, HBO can still reach far more viewers/subscribers via traditional cable than it can via the Internet. The percentage and demographics of cord cutters simply haven’t moved far enough in that direction.

Yet.

Like we said, it’s all a part of a complex conversation. Let’s keep going, looking at some of the hardware that’s driving this potentially game-changing shift.

Disruptive Hardware

The biggest challenge facing cable’s content delivery is the new technologies that are taking advantage of mobile broadband. These are chiefly provided by cellular telephone providers but certainly including any Wi-Fi network with which the user can connect. Mobile broadband is exactly what it says—a service that allows you to access content anywhere you go, at any time, with any number of devices—all while your television and set-top-box are sitting at home, alone and lonely, like some poor kid who was left off the list for the hot party in town.

There are three primary forms of hardware that are driving disruption.

Smart TVs

There was a time when a television was nothing more than a receiver, a device that allowed content to be viewed. That content came via antenna (free) or set-top box (subscription), so the broadcast networks or the cable companies determined the overall viewing menu. TVs were therefore dumb, nothing more than an adjunct to the content conduit. Like much of everything else around us, the Internet has changed this scenario. Today, TVs are equipped with their own technology, allowing for connections to both the Internet and/or HDMI cables—the cables that deliver high-quality digital images from whatever receiving device you are using.

These TVs deliver the traditional broadcast media you may be watching via your cable provider. However, they also allow the viewer to consume a variety of products that are not managed by the Internet service provider (which in most homes typically the cable provider). In short, the cable provider, in selling you broadband service, is giving you a way to work around the television service it would like to sell to you. (How long do we think that is going to last?)

If you’re not interested in trading up to a smart TV, you can accomplish the same reception goal by purchasing a game console. Xbox and Wii both utilize Ethernet connections to deliver content to owners. Or you can use an Internet-enabled Blu-ray player, which also delivers content.

An interesting outgrowth of this technology leap is a movement in the hardware—specifically television—world to actually become the conduit. After all, if all the technology is built into the box you’re selling to consumers, why not get a piece of the content delivery yourself? Again, an exceedingly complex discussion, with no real footholds to date, but a subject of much discussion in 2012. Keep an eye on companies such as Intel, Sony, and LG, who produce a huge percentage of the smart televisions now available.

Smartphones and Tablets

Who can get along without that handy little device that seems to have attached itself permanently to your palm? Smartphones of all varieties—be it Apple, Android, Windows, whatever—now allow users to transfer content from that small screen to the big one in the living room, courtesy of any number of connective devices, with the simplest being an HDMI cable.

Apple, being the tech genius that it is, offers an easier solution, if you’re already invested in the Apple environment. Connecting your iPad or iPhone to your television via an Apple TV receiver by way of the AirPlay network bypasses that cable. More on Apple in a moment.

Laptops

This one has been around for some time. Again, an HDMI cable between your laptop and your television allows you to throw the picture on your laptop screen up to the big device in your living room. In addition, hardware such as Slingbox allows you to connect into your home TV anywhere in the world, enabling subscribers to take their content with them.

Disruptive Conduits

When you have the hardware in place, entertainment content still needs a way to reach that screen, be it big or small. This is where the action is really happening. Because alliances and allegiances are changing constantly, no one really has a clue as to what’s next, and everyone is trying to create the best business strategy possible to keep the revenue flowing in. It is an amazing whirlwind to watch.

Netflix

Long ago and far away, we started our whole discussion of entertainment content with movies—and here we are again. The rental business for movies has morphed into streamed content, and the prime mover in this area is Netflix. Originally started as a home delivery alternative to Blockbuster, the one-time VHS/DVD rental king, Netflix subscribers could order new releases and old favorites, delivered to their doorstep for just a few dollars a month. But as technology progressed, Netflix kept ahead of the curve by developing the on-demand streaming side of their business. At this point in time, streaming far outweighs disc-driven delivery and includes movies as well as television content.

Netflix has put more than one provider’s nose out of joint. HBO refuses to license any of its content to the service. Cable networks have put together huge deals with studios to keep first run movies from appearing in the Netflix library before the premium services have had a go at them. This has left Netflix’s library with more holes than their marketing might suggest, but the company continues to chip away, doing deals with television content providers such as Disney-ABC, CBS, and 20th Century Fox Television. Movie studios providing content to Netflix include DreamWorks Animation, The Weinstein Company, Open Road Films, and Relativity Media.

In late 2012, Netflix announced an alliance that stunned many onlookers, wresting Disney away from Starz, the cable channel that previously had an exclusive deal with the Mouse. Netflix now has the exclusive, gaining access to Disney’s vast library of classics and new releases—as Disney sees fit to release them. Remember, Disney carefully strategizes the release of its classic content.

Even more important, Netflix has made sure that ease of access remains supreme. It provides free applications for smartphones and tablets and integrates click-through with peripherals such as Blu-ray players and smart TVs, where that familiar red icon shows up nicely on the home screen, and in some cases, right on the remote.

But Netflix also provides a word of caution to those who might believe that streaming is supreme. In 2012, Netflix suffered severe customer backlash when it tried to spin off its DVD line into a new brand, Qwikster. The plan was dropped like a hot potato when subscribers who wanted access to both streaming and DVDs howled. The company recovered and then some, beating growth projections by a mile in late 2102 and now serving 27.15 million subscribing households.5

5 “A Resurgent Netflix Beats Projections, Even Its Own,” New York Times, January 24, 2013.

Hulu

Hulu, a joint venture of NBCUniversal Television Group (Comcast/General Electric), Fox Broadcasting Company (News Corp), and Disney-ABC Television Group (The Walt Disney Company),6 streams free, advertising-supported video, with programming provided by over 410 content companies. This includes television programming, movies, and documentaries from providers including FOX, NBCUniversal, ABC, The CW, Univision, Criterion, A&E Networks, Lionsgate, MGM, MTV Networks, Comedy Central, National Geographic, Digital Rights Group, Paramount, Sony Pictures, Warner Bros., and TED conferences.

6 “How Much Extra Cash Does Apple Really Have?” Forbes, December 12, 2012.

Hulu Plus is a premium version of Hulu, streamed to any device, with limited advertising, for a subscription fee of $7.99 per month.

An interesting element of both Netflix and Hulu is what has come to be known as recommendation TV. Because both services know exactly what you’re viewing, they can utilize an algorithm to suggest other shows or movies you might enjoy, driving additional purchases.

Digital Media Receivers

There are several digital media receivers out there, including Roku and Boxee. These devices provide access to streaming media content via high definition television, with interactive capabilities. This content might or might not (depending on the licensing deal) include Netflix, Hulu Plus, Amazon Instant Video, HBO GO, Angry Birds, NBA Game Time, and Pandora Radio. It is nearly impossible to fully define each device, as they continue to change as new opportunities arise, technology changes, and software is updated. In the interest of providing a snapshot in time, here are a few of the current offerings:

![]() Vudu: Owned by Walmart, allows users to rent or purchase films as well as watch streamed content.

Vudu: Owned by Walmart, allows users to rent or purchase films as well as watch streamed content.

![]() Boxee: Allows users to view, rate, and recommend content to their friends through included social platform applications.

Boxee: Allows users to view, rate, and recommend content to their friends through included social platform applications.

![]() Roku: A digital media receiver that allows users to view streamed content through high definition TVs.

Roku: A digital media receiver that allows users to view streamed content through high definition TVs.

And while we’re on the subject...

Apple TV

Grounded in iTunes, Apple TV, also a digital media receiver, offers access to the iTunes library of movies, shows, games—all forms of digital content, available on a transactional basis. It also offers Netflix, Hulu Plus, YouTube, Flickr, iCloud, MLB.tv, NBA League Pass, NHL GameCenter, along with content from Mac OS X or Windows operating systems.

But wait: there’s (potentially) more. The early 2013 rumor mills have been heating up with conversation regarding Apple actually producing a television, not just a digital media receiver. Some say that it will help Apple lock consumers into other iOS-based devices (iPads, iPhones), even as competition from other tablet and phone providers heats up. After all, people replace their televisions an average of every eight years, while other devices, such as phones, may be changed out every two years. If that little device in the palm of your hand allows you to seamlessly interact with content in your living room, you might be less willing to move out of the iUniverse.

Apple is an 800-pound gorilla lurking in the background of the entertainment business, and not just because it launched the smartphone revolution with the sleek and stunning iPhone. Apple is a company that could forever change the hardware/content game in a few simple moves. The company is sitting on a pile of cash that could be worth as much as $158 billion by September of 2013.7 That is a lot of buying power.

Apple already has a stake in content. It certainly has a stake in hardware and software. So what if it used a bit of that cash and purchased Disney—who has made several stunning moves of its own, purchasing LucasFilm (Star Wars, et al.) and Marvel? Or Time Warner (HBO, Cinemax, Turner Broadcasting, CNN, and much, much more)? What if Apple suddenly locked up all of it, together? They could do that with less than half of that pile.

Don’t laugh. Stranger things have happened.

Gray Area...Errr, Aereo

You will note that most of the conduits we have described so far have found some way to play nice in the business model sandbox. Some devices are actually owned by media companies; others pay fees. Now along comes Aereo, and the whole world starts to tilt one more time.

Launched in 2012, backed by Barry Diller’s IAC/InterActiveCorp, Aereo allows subscribers to watch both live and time-shifted over-the-air broadcast content on Internet-connected devices. Aereo launched its service in New York City in 2012 and was immediately the target of a pile of lawsuits, from both broadcast networks and cable providers.

Aereo sits in a strange gray area. It is perfectly legal for any person to purchase an HD antenna and capture broadcast signal at no cost—but that antenna is a fixed device. Aereo has set themselves up as the middleman, capturing those broadcast signals on antennas that are leased to each subscriber, then delivering that content to the subscriber via the Internet. Voila! The subscriber no longer needs to be near their fixed antenna.

Broadcasters are screaming because Aereo circumvents the very healthy retransmission fees cable pays to broadcasters—estimated at 10% of broadcast’s yearly revenue. Cable companies are screaming because consumers can receive and time-shift content without paying cable fees. In an interesting “Huh?” moment, Federal Judge Alison Nathan tossed out a preliminary request for injunction, filed by a consortium of network broadcasters, with the decision based on a case that had established Cablevision’s right to cloud-based streaming and DVR services—in effect, also undercutting any argument cable might have against the service.

In early 2013, at the yearly Consumer Electronics show, Aereo announced that it would be launching service in 22 American cities in 2013. This is about to get really interesting.

Google TV

Google TV integrates Google’s Android operating system and Chrome browser to create a 10-layer overlay on the consumer’s smart TV. Through multiscreening, it allows the viewer to access Internet-based content, including Netflix, HBO GO, and other streaming content currently available (all subscription fees are still in effect; you cannot access on-demand HBO programming if you haven’t paid for the service through your cable provider). While watching content, viewers can also access all other content normally available through the Google browser.

This sets up an intriguing opportunity for content providers to create highly interactive programming. Imagine watching the Masters Golf tournament while simultaneously clicking through to order that new set of Ping clubs. This gives the term “recommendation TV” a whole new—and to marketers, exciting—angle. It could take product placement to a hugely profitable new level.

The multilayer function of Google TV allows for personalized viewing experiences, where viewers can put together their own “home screens”—particularly advantageous for parents who might want to set up a lock-out for their children, keeping little Justin and Tiffany from channels that aren’t allowed.

Disruptive Content

So we have the hardware; we have the conduits. Now we need something to watch. There’s certainly more than enough available through the traditional providers, all of it streaming nearly everywhere. And it’s getting better all the time. Cable networks and channels have been on an original-content rampage over the last several years, ever since AMC’s Mad Men (a program offered to but turned down by HBO) turned into the breakout, break-away hit of the decade, influencing everything from clothing styles to political debates and proving once again that content is king.

HBO, of course, is the reigning champ of original content, showing up at the Emmys, Golden Globes, and Cable ACE awards with a wheelbarrow, every year. But what used to be the also-rans—Showtime, Starz—have been launching their own media missiles of late, with great success. Content comes from everywhere. A small example: Bomb Girls, a program dealing with the lives of World War II Canadian factory workers, originally aired on Global TV, a Canadian broadcast network with 12 outlets in Canada. The original season of six episodes was picked up by Reelz, making the program available to American viewers. The show has developed a loyal and growing following, crossing international lines.

It seems that nearly every outlet with an eye toward eyeball-grabbing is in the hunt now. It isn’t enough to stream just anything anymore. It has to be something unique, something that will sway the consumers to your site, to your subscription package, and original programming is the answer du jour.

Part of what’s moving this forward is the leap in digital technology. It is estimated that the cost of a typical television pilot runs in the neighborhood of $3 million for a 30-minute show. The traditional system gets that pilot on the air for one viewing. If it sticks, great. If it doesn’t, it’s gone.

But the digital universe has delivered both the hardware and the software to the masses. A 30-minute show can be produced for $5,000. It can be launched on the Internet, where it can be viewed, reviewed, tweaked, and relaunched for less than nothing. It can be allowed to grow, gain viewers and traction, and turn into a modest hit on a not-so-modest medium. Are we talking broadcast television numbers? Of course not. But we’re at the root of the revolution, the very start of the seedling.

That nursery is being fertilized by some very large dollars. Hulu now has original programming. YouTube has launched original programming, courtesy of the $100 million YouTube Original Channel Initiative. Why the push? YouTube is now owned by Google—and those original channels will kickstart that same Google TV we just discussed.

Even Netflix has joined the revolution and may have started a new one. In February of 2013, Netflix launched its own House of Cards, a 12-chapter series dealing with skullduggery in Washington (talk about your easy targets). What sets the series aside from the typical launch is this: They made all 12 episodes available immediately.

This is potentially game-changing. Netflix recognized a trend in consumer behavior: marathoning. With all the content now available on the stream, many consumers will simply wait until a series—from any of the networks, broadcast or cable—is available as a whole and then watch it all at once. No commercials, no annoying wait at the end of the cliffhanger—just a straight-through “read,” like a novel. Another interesting feature of the launch is the episodes have no opening flashbacks—those bits and pieces of the previous episode supposed to bring viewers up to date. Marathoners don’t need them, don’t want them, and can give their fast-forwarding thumbs a break.

This might turn out to be the golden age of viewing. As each network ups the ante with new content, every other competitor must rise to the occasion, pumping out even more and faster. The consumer is being treated to a fresh content buffet unlike anything we’ve ever seen.

TVEverywhere

So here we are, with broadcast television, cable television, and now online television. The response from traditional providers has been an initiative called TVEverywhere, launched by Comcast and Time Warner. TVEverywhere is an authentication service that checks to make sure that online viewers accessing streaming content have paid the necessary subscription fees to access said content. In short, it’s a way to make sure that providers who pay networks for the carriage of their shows are not undercut by those same networks placing that content online for streaming.

Summary

Today’s entertainment marketing professionals must stay current with the rapidly evolving digital disruption. Hardware and software are changing by the nano-second. Though digital delivery offers great opportunities to entertainment marketing professionals, it also offers plenty of pitfalls. Read everything that you can in print, digital, or online; attend conferences and conventions; follow the trends; stay informed of new technologies. In the digital world, not doing so could lead to career death.

Before we explore the marketing of some very important entertainment content, sports and music, let’s examine the first mass media: publishing.

For Further Reading

Iordanova, Dina, and Stuart Cunningham, Digital Disruption: Cinema Moves On-line, St Andrews Film Studies; 1st Edition (March 1, 2012).

Vivian, John, The Media of Mass Communication, 11th Edition, Pearson, 2012.