7. Publishing: The Printed Word Goes Digital

In this chapter, we explore the world of the printed word and how it comes to market, investigating books, newspapers, and magazines. Like many other entertainment platforms, publishing is in the middle of its own protracted drama, this one centered on the influence of digital technology—a villain to some and a hero to others. We leave it up to you to decide which it is. In any case, it is redefining this critical business segment.

In the Beginning...

At the heart of all that enchants and engages us—movies, music, television, and art—there is story. Story reflects our innermost yearnings and our greatest fears, allowing us to experience them in a safe place, far from whatever messy business might occur in real life. This is as true in nonfiction as it is in fiction; in orchestral music as in opera. Story is the emotional tagline that pulls us into and through any creative endeavor.

Story does not turn into revenue without some kind of controlled effort at distribution and monetization. Publishing is what takes the author—be it novelist, journalist, or blogger—from simply getting attention to making a living...maybe. The making a living part is rarely based purely on talent. It is, in fact, based on the business of publishing.

Marketing is the underpinning of the entire effort, regardless of the delivery: hardcopy or downloaded digital. This is as true for a single online blog as it is for the millions of Harry Potter books, as applicable to the self-publishing author as it is to the biggest names in the business. The advent of digital self-publishing makes cutting through the clutter more important than ever. The digitization of media has turned this, the first mass medium, into a Wild West never seen before.

From its very inception—the moment Johannes Gutenberg pulled the first page from his printing press—publishing has had many forms of control, some of them socio-economic (not everyone could own a printing press; not everyone could read); some of them governmental (censorship and regulation). But the digital disruption has literally opened the floodgates of access, control, monetization, and marketing, turning the world of publishing on its head.

The traditional model of publishing relied on trained individuals to vet content, controlling the product as it came to press, ushering it out to the market in a specific set of steps. Today, with self-publishing, blogs, and “citizen journalists,” supported by technology that puts the process in the hands of both the creator and the consumer, publishing is battling for survival, in a war that sometimes feels like the French Revolution, complete with mobs of the digerati mounting the barricades of the Internet.

Even the simplest of concepts—the formation of opinion as a tool to grade quality—has been handed over to the masses, especially in the world of books. Good? Bad? Two sides to every story, one that we investigate as we touch on each platform.

So let’s begin with books, starting with the traditional structure of the business.

Books

Book publishing covers a wide landscape: hardbacks, e-books, paperbacks, pocket-sized books, and coffee table books (not to mention books that could serve as coffee tables, given their size). Also, professional publishing, religious publishing, and educational publishing (texts, professional references, workbooks, and support materials developed specifically for elementary, high school, and college).

For basic reference, the following is a quick look at the terminology1:

1 Woudstra, Wendy J., “Trade or Mass Market?,” www.publishingcentral.com.

![]() Books: All nonperiodical hardcover volumes regardless of length, excluding coloring books, and all nonperiodical softbound volumes over 48 pages.

Books: All nonperiodical hardcover volumes regardless of length, excluding coloring books, and all nonperiodical softbound volumes over 48 pages.

![]() Trade Books: Books designed for the general consumer and sold primarily through bookstores, online retailers, and to libraries (“trade,” then, is in reference to the traditional trade markets these books are sold in). Though trade books were traditionally hard cover, in recent years more soft cover trade books have been common. Adult trade books include fiction, poetry, literary comment, biography and history, the arts, music, theater, cinema, popular science and technology, cookery, home crafts, self-help, business, how-to books, popular medicine, sports, travel, gardening, nature, social issues, and public affairs. Many of these books are reprinted in lower priced editions called trade paperbacks or quality paperbacks. Often their original or only appearance is in a paperback edition.

Trade Books: Books designed for the general consumer and sold primarily through bookstores, online retailers, and to libraries (“trade,” then, is in reference to the traditional trade markets these books are sold in). Though trade books were traditionally hard cover, in recent years more soft cover trade books have been common. Adult trade books include fiction, poetry, literary comment, biography and history, the arts, music, theater, cinema, popular science and technology, cookery, home crafts, self-help, business, how-to books, popular medicine, sports, travel, gardening, nature, social issues, and public affairs. Many of these books are reprinted in lower priced editions called trade paperbacks or quality paperbacks. Often their original or only appearance is in a paperback edition.

![]() Mass-Market Books: Books sold predominantly through mass channels that extend beyond traditional trade outlets, such as book and department stores, to include newsstands, drug stores, chain stores, and supermarkets (often the same channels that distribute magazines). Mass market paperbacks are usually printed on less expensive paper than trade paperbacks, and their covers are more likely to attract a mass audience. Mass-market paperbacks are reprints of hard-cover fiction and nonfiction books, some original fiction (some are published only in this format), and original nonfiction. Mass-market books are often sold though the channels that distribute magazines and can also be found online.

Mass-Market Books: Books sold predominantly through mass channels that extend beyond traditional trade outlets, such as book and department stores, to include newsstands, drug stores, chain stores, and supermarkets (often the same channels that distribute magazines). Mass market paperbacks are usually printed on less expensive paper than trade paperbacks, and their covers are more likely to attract a mass audience. Mass-market paperbacks are reprints of hard-cover fiction and nonfiction books, some original fiction (some are published only in this format), and original nonfiction. Mass-market books are often sold though the channels that distribute magazines and can also be found online.

![]() Textbooks: Books designed for classroom use rather than general consumption. This category also includes workbooks, manuals, maps, and other items intended for classroom use. Textbooks usually contain teaching aids, such as summaries and questions that distinguish them from consumer-oriented materials (like trade books). These books are generally sold through college bookstores and are also available online.

Textbooks: Books designed for classroom use rather than general consumption. This category also includes workbooks, manuals, maps, and other items intended for classroom use. Textbooks usually contain teaching aids, such as summaries and questions that distinguish them from consumer-oriented materials (like trade books). These books are generally sold through college bookstores and are also available online.

Please note that for the purpose of this discussion, “e-books” refer to any of the types of books just listed, repackaged and sold as a digital version to be consumed via a digital reading device. The same holds true for “audiobooks,” which are recorded and distributed whether in hard copy (DVD) or as digital downloads.

In the entertainment field, the two most common types of books are trade books and mass-market paperbacks. In North America, the trade publishing world is currently dominated by the Big Six: Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Random House, Penguin Group, and Simon & Schuster. We say “currently” because at the time of this writing, at least two mergers seem to be in the works, possibly leading to a “Big Four.”

The fiction category of books represents the greatest percentage of books sold in any category. These are books identified as appealing to a mass audience and providing relaxation and engrossing reading. They are often described as “mental transportation”—escapism in a small package.

As entertainment, fiction is the focus of the book portion of this chapter

Something for Everyone

Within trade and mass-market publishing, books are further defined by the audience they serve. The term “genre” is used across the entertainment world to describe particular categories of writing, music, movies, television, and radio content. It helps content providers in all areas understand and measure the popularity of one genre against another, as well as strategize marketing plans for the audiences they serve. In publishing, the tracking of genres guides the decision-making process for allocating scarce resources, especially when it comes to paying advances or creating marketing support.

Some literary critics have been quick to attach a stigma to the marketing-driven concept of genre. Writers like Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett created original, high-quality works but were never widely considered to be “literary” by American critics of their day, though others have ranked them in the top 100 American writers. Publishers catering to mass audiences and pop culture seem to care little for literary appellations, given that genre publishing has been very good to the whole industry.

Many genres have no clear-cut single descriptive but instead have major and minor subcategories. There is science fiction (sci-fi), which splits roughly between futuristic (Herbert’s Dune) and sword-and-dragon fiction (Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings). Mystery books also fall into several popular and even niche subgenres. These include cozy reading (Agatha Christie, Nora Roberts), noir (Jim Thompson, James Ellroy), hard-knuckle (Mickey Spillane), and a number of other categories of distinction. Westerns still have their own shelves. Also, books of humor, poetry, plays, and African-American and gay literature find room on separate bookstore shelves, reaching for separate and distinct audiences.

Case in Point: Romance Publishing

Romance publishing continues to be evergreen, maintaining a hardcore group of readers that other genres envy. Consider these stats, courtesy of the Romance Writers of America2:

![]() Romance fiction revenue increased from $1.355 billion in 2010 to $1.368 billion in 2011. It remains the largest share of the consumer market at 14.3%.

Romance fiction revenue increased from $1.355 billion in 2010 to $1.368 billion in 2011. It remains the largest share of the consumer market at 14.3%.

![]() Thirty-one percent of the romance book buyers surveyed consider themselves avid readers (almost always reading a romance novel), and 44% are frequent readers (read quite a few romance novels). Only 25% are an occasional reader—someone who reads romance on and off, like when on vacation.

Thirty-one percent of the romance book buyers surveyed consider themselves avid readers (almost always reading a romance novel), and 44% are frequent readers (read quite a few romance novels). Only 25% are an occasional reader—someone who reads romance on and off, like when on vacation.

![]() Fifty-seven percent of avid readers and 43% of frequent readers have been reading romance for 20 years or more. Even 41% of occasional readers have been reading romance for 20 years or more.

Fifty-seven percent of avid readers and 43% of frequent readers have been reading romance for 20 years or more. Even 41% of occasional readers have been reading romance for 20 years or more.

![]() On the digital side, e-book sales of romances have proportionally doubled in one year, up from 22% in the first quarter of 2011 to 44% in the first quarter of 2012. This is in comparison to the total market, where only 26% of books are purchased in e-book format. Ninety-four percent of romance buyers read romance e-books (includes purchased and free titles).

On the digital side, e-book sales of romances have proportionally doubled in one year, up from 22% in the first quarter of 2011 to 44% in the first quarter of 2012. This is in comparison to the total market, where only 26% of books are purchased in e-book format. Ninety-four percent of romance buyers read romance e-books (includes purchased and free titles).

When the term “romance publishing” comes up in conversation, the imprint most people think of first is Harlequin Romances, and with good reason. According to Harlequin’s statistics, the Toronto, Canada-based company publishes over 110 titles a month in 31 languages in 111 international markets on 6 continents. These books are written by over 1,200 authors worldwide. Harlequin had 390 bestseller placements in 2010 that enjoyed a total of 1,048 weeks on bestseller lists. Since its inception, it has sold approximately 6.05 billion books.

The umbrella of Harlequin Enterprises’ yearly releases includes at least six titles from Harlequin, several from Silhouette, Steeple Hill (Christian Romance), Mira (longer brand-name romances), and Gold Eagle, an action-adventure series described as romances for men.

In considering crossover appeal, one should note that romance—stories of love with a happy ending—was the inspiration for The Bachelor and The Bachelorette, the competitive dating reality television series.

Speaking of inspiration, every writer sitting in Starbucks, toiling away on his or her laptop, dreams of one day being published. That particular romantic dream has kept more than one scribe working toward completion of the marathon known as a novel. But long as it may take, writing turns out to be the easy part. Getting published? A journey all its own.

In the age of digital disruption, writers have a choice in how they might bring their books to market: They can follow the traditional route, or they can self-publish. It’s a safe bet to say that many writers would prefer to be picked up by one of the Big Six, but there have been some breakout successes in the self-publishing world.

Let’s start the discussion with a look at the tried-and-true method.

Getting Published: The Traditional Route

How does a manuscript even reach the stage of consideration for publishing?

In years past, publishers had staff employees called “readers.” Their job was to screen manuscripts, many of them unsolicited. In the 1980s, to cut overhead costs, publishers dispensed with the role and began to return unsolicited manuscripts unopened. The “readers” were replaced by authors’ agents. The agents, at no cost to the publisher—but with the speculation of 10%–15% of an author’s royalty—screen manuscripts for quality and anticipate marketing considerations of the appropriate publishers of each manuscript. A successful agent follows the publishing industry, usually focusing on a particular segment or two. They know the patterns, trends, and personalities of the publishers. Some agents even act as packagers of books, going so far as to deliver a book ready as a specific type or genre to an appropriate publisher.

Before a publishing contract is extended to any author, someone has made a considered study of the proposed book to determine the return on investment (ROI). The acquisition editor, the person who most often signs an author, considers several cost factors, including plant costs (overhead of running the business), physical costs (such as PPB—printing, paper, binding), author royalty, and marketing. Increasingly, one of the key ingredients of this study is whether the product will bear its own marketing cost. All of this is factored against the discounts that must be extended to wholesalers and retailers. The editor then makes a calculated guess as to whether a proposed book will meet or exceed sales goals based on the company’s capacity to sell within a reasonably defined market.

But how does the editor know the size of each book’s market? Trade and mass-market book editors do not have the luxury of a somewhat predictable market segment, as in some educational or technical/trade markets. In college textbook publishing, for instance, the market segment is decided by how many students are sitting in classes that focus on that subject. In addition to this total size of the market, the college text editor must know the competition—the other books currently used in that market segment, their strengths and weaknesses, and whether the author or authorial team has the background, credibility, and knowledge to author a book able to displace that competition. In short, there is a relatively forecastable market with some finite and promising parameters.

This is not the case for the riskier area of trade or mass-market books. An acquisition editor of these books must consider the author’s reputation and quality of the manuscript. If the author’s name is Stephen King or John Grisham, the reputation part is a no-brainer. But if it is an emerging author like Donna Tartt, who, in 1992, received a $450,000 advance from Knopf for her first book, The Secret History,3 then the quality of the writing must speak for the book’s potential—and then some. In today’s more protracted publishing world, such advances for a new author are the stuff of dreams.

3 “Tartt’s Content,” Sun Sentinel, September 27, 1992.

In times past, it was common to bring a book out first in hardback, and if it did well, it would appear about a year later as a paperback. By late in the twentieth century, it had become more common to bring an emerging author to the public through a series of paperbacks before shifting to hardback status. Many emerging authors no longer have their first books come out as hardbound, but must earn that status.

Or they can self-publish.

Self-Publishing

So, you’re a writer. You’ve managed to publish in print and online, in journals such as Third Coast, Storyglossia, Timber Creek Review, 34th Parallel, and Rubbertop Review. But no matter how many queries you’ve sent out, you get nothing more than “looks good, keep trying.” Convinced that you have something to say, you decide to take matters into your own hands and self-publish.

While self-publishing has always been with us, the reach of this approach used to be highly limited until the Internet came along. But that only opened the door—the self-published writer still needed to invest in printing, storage, and marketing. It was the advance of print-on-demand, allowing for high-quality end-product created order by order, that broke the door down.

Today’s writers have hundreds of resources for getting their books to print and to market. Sites like Lulu, SmashWords, and BookBaby take writers through the paces. The finished product might be hardcover, or it might be an e-book, meant to be consumed via any of the growing number of tablet devices: Nooks, Kindles, iPads, and so on. Amazon has become a prime mover in this area with CreateSpace, offering design, editing, marketing, and direct links to the Amazon empire, including Amazon international sites as well as the Kindle store.

The number of self-published books produced annually in the U.S. has nearly tripled, growing 287% since 2006, and now tallies more than 235,000 print and e-titles.4

4 Self-Publishing in the United States, 2006–2011: Print vs. Ebook, Bowker, October 23, 2012.

Self-publishing has its pros and cons. It’s time-consuming; it demands knowledge of good visual design; your book still needs to be discovered. And there’s the not-so-simple task of getting past your own ego regarding not being good enough to make it with the Big Six. But there have been breakouts, including a series written by E.L. James that took the world by superstorm in 2012, beginning with her first book, Fifty Shades of Grey, and followed by Fifty Shades Darker and Fifty Shades Freed.

This trilogy had even humbler beginnings than many self-published novels. It started off as online fan fiction, based on the popular Twilight series. Originally titled Master of the Universe, the fanfic was met by protest from enough Twilight fans that James removed the story and placed it on her own web site. She eventually reworked the piece, renaming the characters so as not to run afoul of copyright with Twilight, and released Fifty Shades of Grey through the Writers Coffee Shop, an Australia-based virtual publisher. It was originally released as an e-book and a print-on-demand paperback.

The book—poorly written and heavy on what has come to be known as “mommy porn”—took off via word of mouth and was picked up by Vintage, an imprint of Random House. To date, it has sold more than 65 million copies worldwide. Movie rights have been picked up by Universal Pictures.

Success by sex, we say. Never doubt the power of porn, like it or not.

When, Where, and to Whom

Meanwhile, back at the traditional publishing route.

The publishing of trade books happens in selling seasons. The spring release of titles anticipates the selling window of July through September and is heavily weighted to beach reading and light summer reading. The anticipation of Christmas season sales leads to a fall release of books. The fall list is heavier, especially in the nonfiction genres and specialty books arena. Each year, the NPD Group, an international provider of marketing information, makes available a Consumer Research Study on Book Purchasing, which is published by the American Bookseller’s Association (ABA). This report confirms that most books are sold in the second half of the year and that the Christmas sales window shows the most aggressive growth. However, some publishers are even going to three-season and monthly selling.

The NPD report also confirms a demographic shift in book buying. The Pacific region and Mountain region combine for almost 30% of all books sold, while the New England states, including Boston and New York, command only 5%. Even with 15% more sales from the Mid-Atlantic States, the east coast must bow to the west when it comes to book sales.

Who is the average book buyer? Not surprisingly, it is someone with disposable income. The greater proportions of books were purchased by those individuals with the largest incomes, most of whom are Baby Boomers. The increasing number of individuals receiving college degrees since the 1960s has encouraged book sales, while also contributing to the information explosion that led into the new millennium. Once a book is ready to release to the public, it must find its way to consumers.

Distribution Channels

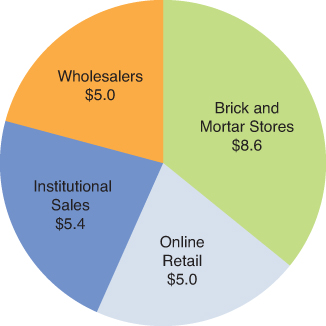

In the past, wholesalers such as Ingrams and Baker & Taylor were the prominent middlemen in the distribution chain. Because it consumed too much time—and too many inventory dollars—to keep books in stock, retailers would order and reorder from the wholesalers. However, Barnes & Noble and Amazon.com order most of the books stocked directly from the publishers, thus enhancing their margins. Today, wholesalers have yet to diminish in importance, having created their own print-on-demand divisions, such as Ingram’s Lightning Source. This service is especially important to independent booksellers, who cannot hold large inventories of books (see Exhibit 7-1).

The rise of online retailing began with Amazon.com.

Amazon Changes the Game

Ten years ago, Amazon billed itself as the “world’s largest bookstore,” angering—to the point of lawsuits—the traditional brick-built stores that laid claim to that title. Amazon has since gone on to be one of the world’s largest stores, period, upending not only the Borders (now defunct) and Barnes and Noble chains, but the publishing industry itself.

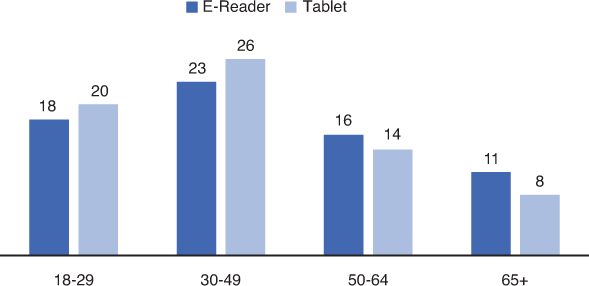

The most significant step in this process was the introduction of Amazon’s e-reader, the Kindle, quickly followed by products developed by others, including the Nook (Barnes and Noble) and applications for tablets such as the iPad, Surface, and various Android-based devices.

Today, an increasing portion of the U.S. population reports using e-reading devices as the primary way they consume books (see Exhibit 7-2).

It follows that if books are no longer printed, the supply chain that provides that service might or might not be necessary—at least in the eyes of Amazon. Their part in the disruption of publishing is to become the publisher—and the distributor, and the agent, and the reader, and the marketing department, all through its previously mentioned self-publishing application.

It remains to be seen how the rise of e-books will play out. Actual sales of e-books are hard to track. Publishers and distribution outlets are not the most forthcoming when it comes to sharing this information. No one has any full knowledge of what is being self-published. But in 2011 the Association of American Publishers (AAP) and the Book Industry Study Group (BISG) joined forces to compile better sales data on the publishing business in their BookStats project,5 with much of the information based on statistical modeling.

5 “Looking at US E-book Statistics and Trends,” www.publishingperspectives.com, October 3, 2012.

Results from the BookStats study demonstrated that, based on publisher’s receipts, 2011 trade publisher e-book revenue was at an estimated $1.97 billion, comprising almost 16% of trade dollars. E-book totals in 2010 were $838 million, accounting for 6.7% of trade sales. Adult fiction drove the e-book gains, more than doubling to $1.27 billion from $585 million in 2010 and comprising 31% of dollar sales within that category.6

6 Ibid.

These figures do show a leveling off from prior years. There could be a variety of reasons for this: The market of those who would be considered users of that device might now be saturated. The novelty may have worn off. And it simply might be that no matter what, the feel of a book in your hand—and the ability to tell how far you’ve gotten in reading it simply by looking at the bookmark—may prove to have some value yet.

Listen Up: A Word about Audiobooks

One fast-growing segment of the publishing industry is audiobooks, the digitized versions of bestsellers old and new, that are available either via download or on CD. To no one’s surprise, Amazon is also a big player in this niche, having purchased Audible.com.

Consider this data from the Audio Publishers Association, published in 2012:

![]() The estimated size of the audiobook industry is now $1.2 billion.

The estimated size of the audiobook industry is now $1.2 billion.

![]() The total number of audiobooks being published doubled over the past seven years.

The total number of audiobooks being published doubled over the past seven years.

![]() Audiobook downloads continued on a growth trend representing 42% of dollar volume (up from 29% in 2009).

Audiobook downloads continued on a growth trend representing 42% of dollar volume (up from 29% in 2009).

![]() In the past 5 years, downloading has grown 300% by dollar volume (from 9% in 2005) and 150% in terms of units (from 21% in 2005).

In the past 5 years, downloading has grown 300% by dollar volume (from 9% in 2005) and 150% in terms of units (from 21% in 2005).

![]() The CD format still represents the largest single source of dollars but showed slight declines overall in 2012—54% of revenue (down from 58).

The CD format still represents the largest single source of dollars but showed slight declines overall in 2012—54% of revenue (down from 58).

![]() The majority of sales (90%) continue to be in the unabridged format.

The majority of sales (90%) continue to be in the unabridged format.

From a business perspective, audiobooks have their challenges. First, there are the copyright laws, which protect newer books, but many of the classics fall outside of these regulations. And then there are the complexities brought about with the production of the recording. Audiobooks, by and large, are not just simple recordings of someone reading from the original text. There may be some editing involved, and then there is the addition of the “voice”—the person who actually does the recording, often a fairly well-known actor or actress who brings his or her own contractual agreements into the mix. Add the studio time and the recording artists who heighten the tension with the background music, and you have full-scale production.

From the consumer’s perspective, audiobooks are a great way to catch up on classics and new releases, providing hours of listening pleasure via iPhone or Galaxy or car stereo systems.

Other Retail Outlets

Anyone who has visited a Walmart, a Sam’s Club, a Target, or a host of other such stores has seen whole skids of books available at tremendous discounts. Grocery chains have sections dedicated to books; gourmet groceries have health and cookbook sections. In mass marketing terms, it’s easy for people to buy books in a place where they already shop. Drugstores and supermarkets are naturals for mainstream entertainment products.

What do the huge purchases of books by all of these retailers mean for publishers? A greater laydown (the number of copies of a book that can be presold and ready to ship the day of the book’s release) for books already destined to succeed, primarily. Buyers committing discount resources to this kind of product tend toward the no-brainer books—those by Stephen King or John Grisham or books already enjoying long-term status on The New York Times’ bestseller list.

But getting a book into distribution does little for its sale unless the public has been thoroughly made aware of its presence.

Marketing Books

The marketing of each book usually depends on a marketing professional who’s intimately aware of the best and most cost-effective methods for a publisher in a marketplace that is changing rapidly.

The Book Release

As with many entertainment products, the debut of a new product is trumpeted through a release process.

Until recently, trade shows and book fairs were highly significant events in the release cycle. The ABA’s annual event was once a premier launch spot, as were the Frankfurt, Bologna, and Peking book fairs. But the one-third drop in small store membership in the ABA—severely hit by the economy and the Internet—lowered the impact of these events because buyers at major chains and wholesalers are handled by specialized representatives of major publishers. The cost of attending such meetings is high; in some cases, it becomes more economically feasible to merely court the big buyers of chain stores directly. Book fairs such as BookExpo America and regional festivals like the New York City Book Fair continue to have an impact on a book’s release but have nowhere near the drum roll of previous days.

Because bigger, entertainment-savvy companies have begun to show dominance, the publicity and promotion of a major book release has come to resemble the release of a movie, with a fanfare of reviewing, space ads, and high-profile signings in large cities. But you don’t have to visit many bookstores to figure out that not every book is a bestseller. In fact, a significant portion of the trade book business, including profits, is composed of midlist and other levels of books. Like books that sell in bigger numbers, books that sell only a few thousand copies also have to be marketed. Momentum-building is even more important for these books but must be accomplished on a smaller budget.

In any case, there are several marketing approaches that are common to all types of books.

The Classic Approach: Sales Calls

A portion of book marketing has been consistent through the years. Major publishers staff sales representatives who call on bookstores before a book is released. These reps seek to reach an expectation about each book’s laydown. For the large chains, there is often a separate, more-experienced rep assigned the task of dealing specifically with their needs.

A marketing staff or marketing manager supports the sales reps’ effort by considering the market position of the book, examining the competition (whether direct or nearly direct), and preparing a tip sheet about the book that reduces its salient features to a selling format. These tasks may have already been anticipated at signing by the acquisition editor; in that case, the marketing manager acts as a facilitator and communication link to the sales force.

In the case of trade books, the tip sheet is often composed of the same sorts of comments a reader sees on the back cover or inside the dust jacket of hardbound copies. The marketing department is responsible for the preparation and dissemination of all such book descriptions, as well as press releases (where appropriate). Marketing also coordinates the timing of the book’s release with events like meetings, festivals, a breaking news story, a film release—any event that can substantially support the book.

Backlist Sales: You Oughta Be in Pictures

Backlist books (those formerly published by an author) can become another important marketing tool. The moment a new book by a well-known author is released, the distribution machinery goes into gear. All of the author’s former novels are rereleased—often with new covers—and either packaged as a set or displayed next to each other. This strategy is based on a critical tenet of successful entertainment marketing: No one can see or read everything when it is first available. Thus, every entertainment product needs multiple “windows of opportunity” to be seen and enjoyed by the widest possible audience.

Movies based on books are terrific for this second round of selling. According to Nielsen,7 Elizabeth Gilbert’s memoir, Eat, Pray, Love, saw a spike in sales in mid-2010, just prior to the August 13 opening of the Julia Roberts movie of the same name, with 94,000 units sold in the week ending in August 1 alone. This was the same number of total units sold for the entire 2006 year, when the book was first published. In 2010, the book sold more than twice as many copies (721,000) as all of 2009 (333,009).

7 Nielsen Wire, “Book, Movie, Love: Best Sellers and the Hollywood Bounce,” August 10, 2010.

In the same article, Nielsen pointed out two other book-to-movie titles that got a bounce from movies:

![]() Dear John by Nicholas Sparks saw an uptick in book sales concurrent with the February 2010 release of the movie, contributing to over 1 million units sold during 2010, nearly half of the book’s 2.4 million total sales.

Dear John by Nicholas Sparks saw an uptick in book sales concurrent with the February 2010 release of the movie, contributing to over 1 million units sold during 2010, nearly half of the book’s 2.4 million total sales.

![]() My Sister’s Keeper, based on Jodi Picoult’s 2004 book, was released to theaters in June 2009, five years after the original publication run. This novel achieved its highest weekly sales number during the week of the film’s release, with 81,000 units sold.

My Sister’s Keeper, based on Jodi Picoult’s 2004 book, was released to theaters in June 2009, five years after the original publication run. This novel achieved its highest weekly sales number during the week of the film’s release, with 81,000 units sold.

In addition, titles can enjoy repeat sales when a picture of the star of the movie replaces the original cover. Tom Cruise on the cover of The Firm, Julia Roberts on the cover of The Pelican Brief, and Danny DeVito on the cover of The Rainmaker all built additional sales for author John Grisham. Leonardo DiCaprio is driving new sales of The Great Gatsby in 2013. All served to build the identity of these authors as stars—and brands—in their own right.

The tie between Hollywood and publishing is deep and strong, but sometimes it may feel like a chicken or egg relationship. As intellectual property (IP) has gained more and more value—thanks to the copyright/IP battles of the late twentieth century—recent moves in branding have created even tighter linkage.

For example, James Frey might have found himself in very hot water after exaggerating claims in his 2003 memoir A Million Little Pieces, but he found a new niche in the publishing world with his venture, Full Fathom Five, a self-labeled “IP factory.” Full Fathom Five works with a stable of (some say grossly underpaid) writers, many fresh from MFA programs, to package multimedia deals. What may first appear as a book has already been wined and dined in TV, animated features, movies, coloring books—you name it.

The first successful Full Fathom Five package began with the I Am Number Four blockbuster, a Young Adult (YA) sci-fi novel that went from bestselling book to series to the big screen as a collaboration between Disney and DreamWorks. Recent efforts are focused on Little Shaq, an early-reader series being developed with Shaquille O’Neal, the basketball great. Along with TV, Full Fathom Five sees even bigger potential, expanding the concept into a Little League-like youth basketball program.8

8 “How James Frey’s ‘IP Factory’ is Re-imagining Book Packaging,” www.publishingpersectives.com, January 17, 2013.

This type of packaging isn’t new, of course. Much hullabaloo occurred in 2000, when then-editing superstar Tina Brown teamed up with Harvey Weinstein of Miramax and Hearst Magazines to launch Talk magazine, ostensibly to create multiplatform stories. The project flamed out two years later, with nothing much to show for the effort.

Direct Marketing

Direct marketing, while one of the most expensive ways for publishers to market, can be effective if the target marketing is accurate, the numbers are significant enough for the advantages of a bulk mailing, and the price point is high enough to make the return hit a breakeven point as early as possible. Direct mail typically is now done only on niche books, and those are almost exclusively high-price books because a good response rate can be in the area of 2%.

However, books purchased through direct marketing account for a higher profit margin because customers pay list price and no discount is needed for a wholesaler or large retailer. An additional advantage for the publisher is that sales of the book through regular channels will also benefit because a mailing will help drive those sales through regular retail and Internet channels. These additional sales usually offset any concerns by vendors or reps who do not receive commission on books sold through direct marketing means. In fact, a direct mailing can be billed to reps as an additional advantage to their sales effort.

Some of the best ways to identify a target market for direct marketing are through magazine subscription lists, which have usually already identified a niche that corresponds with the book’s subject. In the case of a nonfiction mainstream title, there may be meetings, conferences, or special interest groups (SIGs) that can be approached by mail. Email outreach is done through “permission marketing,” in which the e-vendor first asks if it is okay to send such emails and provides easy means to be removed from lists for such solicitations. Email marketers report response rates equal to or higher than regular mail approaches for considerably lower costs.

The Importance of Reviews

When the subject of book reviews is mentioned, The New York Times book review always seems to come to mind first. For years it has enjoyed a prominence that belies the fact that, according to U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of the Census information, more books are now sold on the Pacific coast than in all the New England and Mid-Atlantic states combined. Almost every Sunday paper offers book reviews in a Living or Entertainment section, and free-circulation papers (those that thrive on advertising dollars while listing local entertainment) also include book reviews. The Los Angeles Times book review has also established itself as a pillar of early insight, while whole magazines are dedicated to books, among them Publisher’s Weekly, which also provides advance book reviews.

But it is The New York Times book review list that has become the “no-brainer” marketing signal for vendors to buy—and buy in quantity. As such, it receives a stupendous proportion of advance copies, or cranes, of all books published. This advance version of a book is sent to newspapers, magazines, and Internet review sites before the book ever rolls off the printing press and is bound in its final form. In some cases, the advance copy is nothing more than a bound manuscript copy, often with errors still in place. In other cases, “folded-and-gathered” sets of galley proofs or page proofs are bound and sent, these too often containing errors that the authors and editors hopefully weed out before the book is published. The object for a publisher is not only to gain momentum, but also to get lines from the reviews—“blurbs”—that can appear on the jacket of hardbound and paperback copies.

Blurbs can also be requested from other established writers. There is usually an honorarium (paid fee) associated with these, although some authors are quite willing to promote their fellow authors. A blurb also helps the reader decide to buy a book—if Stephen King liked it, then I will. That became so true that Stephen King now draws an almost unflinching line against doing any more blurbs.

The Power of Publicity—The TV Talk-Show Circuit

Book promotion helped supply content for early television talk shows—Jack Parr’s hour-and-a-half version of The Tonight Show featured thoughtful conversations on new releases by a wide range of authors—but the medium has long since given way to book conversations limited to film and TV personalities plugging their own works.

However, other talk shows emerged. An established author—or one with a unique spin—might sit with Ellen DeGeneres or Charlie Rose and build the audience’s awareness of the author’s work. The talk-show format lends itself well to this type of promotion because the author’s appearance also constitutes an endorsement by the talk-show host or hostess.

By far, the show with the most impact on book sales was Oprah. Oprah Winfrey brought books back into American conversation, choosing titles for her Book Club that ranged from new releases in the early goings to old favorites and classics in the later years. Getting Oprah’s imprimatur was golden. The 70 titles selected for her O-branded special editions sold 22 million copies in the decade leading up to 2011, when Oprah moved from her daily show to her own network.

Although some might argue that certain books might have done well on their own, there is no disputing the impact her imprint had. Consider the following: chosen as Oprah Pick #63 (September 17, 2009), Say You’re One of Them by Uwem Akpan (Hachette) sold 47,500 units together in trade paperback and hardcover. The Oprah trade paperback sold 405,000 units—an 853% increase.9

9 “The Oprah Effect: Closing the Book on Oprah’s Book Club,” Nielsen Wire, May 20, 2011.

Oprah promises that her new OWN network will continue to feature book conversations and selections. In any case, shows such as Oprah have a narrow window of opportunity for the number of guests per year. Therefore, publishers tend to promote only their top books on the show. This makes local and regional shows a much more commonly used media for the majority of the business.

Radio Interviews

One proven way to get exposure for a book is for the author to be a guest on a radio talk show. The audience for these shows fill particular niches, each with its own interest in reading material. Howard Stern has a slightly lower income following; Dr. Laura Schlesinger reaches over 20 million listeners on more than 450 stations. Sixty percent of NPR listeners read books for leisure, in contrast to 38% of the general U.S. population.10

10 NPR.

Radio stations with an all-news or talk format are always hungry for guests. Regional format shows are often eager to bring a local author’s work to light. But how to cast beyond that? A good publicist will be aware of all promotional opportunities and will include radio among the early targets for exposure and momentum-building. A great example of the power of radio is the phenomenon of Chicken Soup for the Soul, which was first advertised in Radio-TV Interview Report. It climbed to number one on The New York Times bestseller list and has engendered a family of clones the likes of which publishing has not seen in a while: Over 200 titles extend the Chicken Soup brand. There are over 100 million copies in print in 54 languages.11

Book Awards

Awards sell books. A few of the publishing awards given each year include the Man Booker Prize, the National Book Award, the Caldecott Medal, the Newberry Medal, the National Book Critics Award, the Circle Awards, the PEN/Faulkner Award, the Macavity, the Edgar, the Anthony, and the Shamus (the last three are all given to books in the mystery genre). Oddly enough, the Nobel Prize in Literature seems to mark the death knell of a writer—many who receive this distinguished award rarely ever write another significant book. However, the sales of all that author’s books get a boost that usually exceeds beyond the author’s lifetime.

Can a publisher help an author win an award? In most cases, the integrity of the award dictates that the nomination and decision process be made by impartial judges, members of the award-granting organization. But a top-flight trade acquisition editor knows when he or she has signed a book capable of winning an award and will take every step possible to see that copies of the book reach those who nominate or judge such annual award events.

Some emerging publishers have cut several steps from the process by using a contest to select books for publication and then promoting the book with the publisher’s award. This is a particularly—ahem—novel concept, but only one of many new approaches to entice readers.

Discoverability

Beyond the commercial sale of books to distribution outlets and the mass marketing that occurs for certain titles, the life of a book is driven by the number of consumers that buy. But with all the books in print or in e-form—and it is a number that grows exponentially, given self-publishing—how does a reader actually find the right book to read? Readers—especially voracious readers, the ones always on the lookout for something new and engaging—discover books in many ways.

Populist Reviews

Digitalization has brought consumer dominance to much of the media, and this certainly is true in online book reviews. And of course, given its presence in the publishing world, nowhere does this command bigger attention than on amazon.com.

As helpful as some might find Amazon reviews, they have lately come under attack. After all, it doesn’t take much more than a few of your best friends’ opinions to light up the ranking chart. Amazon has stated that it is taking steps to police this, but it’s hard to imagine how they might do so. In addition, the site gained attention shortly after the release of a biography on entertainer Michael Jackson, when fans of the Gloved One stormed the listing for Untouchable: The Strange Life and Tragic Death of Michael Jackson, by Randall Sullivan. Swarming, the fans peppered the site with one-star listings, managing to erase several favorable reviews. This ravaging horde took credit for Amazon halting the sale of the book for a short time.12

12 “Swarming a Book Online,” New York Times, January 20, 2013.

Social Networking

Social networking sites are hot in the book world, offering readers more than just a review. Facebook, of course, gets lots of attention as a way to reach out to readers. Goodreads, an online site (with the ubiquitous, and some would say, annoying tie-in to Facebook), offers members space to chat about their favorite authors, rate books, write reviews, and interact on topics of the day (“readers: do you highlight?”). It also offers the ability to interact with the authors themselves, many of whom have their own pages at the site, filled with photos, blog-thought, and tweets.

And then there’s Pinterest, which in many ways feels almost antithetical to the idea of marketing a book. The site is like stepping into a howling mass of visual screaming, with everyone clamoring for their bit of attention. Is this really where book lovers go to find the next great read?

No, says Peter Hildick-Smith, founder and CEO of the Codex Group, specializing in book audience research and prepublication testing. According to a presentation made by Laura Hazard Owen of paidContent, presented at the January 2013 Digital Book World conference and quoting Hildick-Smith, while 61% of book purchases by frequent buyers may occur online, only 7% of those buyers said that they had discovered that book online. Brick and mortar bookstores account for 39% of purchase, with a 20% discovery share.13

13 Abrams, Dennis, “Is Online Book Discovery Broken? Here’s How to Fix It,” www.publishingperspectives.com, January 18, 2013.

This, then, is the true problem facing marketing professionals who turn to the Internet. It is by no means the be-all-and-end-all and in fact, offers far more pitfalls than promises. Although the Internet offers much to many, it can simply be noise personified. Trying to thread your way through the din is tricky. Yes, it’s helpful—even wonderful—once the book has gotten a following, but as a discovery tool, it has yet to level off.

What does continue to work is good old-fashioned word-of-mouth, delivered through hundreds of thousands of casual book clubs scattered across the United States. On any given night of any week, hundreds of people are sitting in living rooms or bars or restaurants, talking about this week’s book and picking another for the next. Being discovered—and passed along as a favorite—by these groups can accomplish a lot for independent marketing efforts.

Finally, a bit of insight from the Romance genre. According to Bowker Monthly Tracker (New Books Purchased, Q1 2012),14 buyers become aware of romances through the following ways:

14 As reported by Romance Writers of America.

![]() In-store display/on shelf/spinning rack

In-store display/on shelf/spinning rack

![]() Read an excerpt from the book online

Read an excerpt from the book online

![]() Received recommendation from a friend/relative

Received recommendation from a friend/relative

![]() Author’s website

Author’s website

![]() Read a teaser chapter from forthcoming book in a book they were reading (print)

Read a teaser chapter from forthcoming book in a book they were reading (print)

![]() Online retailer recommendation on a retailer website

Online retailer recommendation on a retailer website

Less influential awareness factors included online customer reviews, best-seller lists, e-mails from retailers, a teaser in a book read online, a book review, and direct mail/catalogs.

Author as Marketer

Today, it’s not enough to write the book (or even self-publish it). If you want to build sales, you need to build relationships with your readers, and, unlike the olden days, when that might mean book tours or public appearances, today you must add blogs, author websites, and tweeting.

You might, in fact, wonder when you will actually have time to write.

Small publishers, some emerging publishers eager to fill niches left behind as too midlist by larger houses, and even the larger houses themselves are encouraging authors to become part of the marketing push. Today’s authors are asked to initiate book-signing tours, create websites with links to the publisher or booksellers, and/or their agents or hire publicists15 to help coordinate events and promotion.

15 A “publicist” fulfills a different role than an agent and is often more responsible for promotion, including the building and maintaining of momentum. Self-published authors and authors of books published by small presses can find the hiring of a publicist a huge boost, though the significant cost may offset some of the advantage.

These publishers either make their preference for proactive authors clear early or bring up the subject during the book-signing process. In some instances, however, the authors themselves may become the focus of the publisher’s marketing spotlight.

Branding

As in most entertainment sectors, niche marketing has played a role in expanding the business of publishing. For example, westerns, action-adventure, and spy novels have always been a hit with a male audience from 25 to 65, while romance books, both contemporary as well as historical (known in the business as “bodice-rippers”), have appealed to women readers from 25 to 65. Mystery books, with many subgenres, have some crossover appeal to both men and women. Vampire novels—from Anne Rice to the Twilight series—have a consistent following within the category, including line extensions or follow-stories arising from the original story line.

So, how does a publisher build an “evergreen,” or sustained revenue stream, in these reader favorites? The answer is through marketing—more specifically, through brand marketing.

Branding the Genre and the Author

Many imprints have grown an identity that has become part of the public’s brand sense of that line. Knopf and St. Martin’s have carved names for themselves as publishers of solid mystery fiction. When Otto Penzler first formed Mysterious Press, he wanted to leave no room for confusion about the brand focus of that imprint. Likewise, TOR made its brand presence known with a focus on science fiction.

However, it is usually the author rather than the imprint that becomes the brand. A customer falls madly in love with an author’s style and storytelling technique, building a need to read another of the author’s books. The beauty of this phenomenon is that older titles gain as much as do new releases; when a reader gets hooked on an author, he or she will search out all of that author’s work.

The responsibility of the publisher is to manage the production or writing of the popular author’s next book and to build awareness among the readers that a new book is on its way. All of this is performed successfully when a publisher builds the author into a celebrity, surrounding the author’s books with a blockbuster halo and building the author into a recognizable and ever-present brand.

The author as a brand is similar—though not identical—to the movie or TV star as a brand. In either case, the audience finds sufficient areas of appeal and the desire to spend time and money on products attached to the star brand. These industry icons are described as bankable: having the ability to take a subject and turn it into a money machine rather than a loss leader. James Patterson, David Baldacci, and Robert Ludlum are spy-thriller series brands; Stephen King and Dean Koontz are giant horror series brands; Janet Dailey and Nora Roberts are superstars of the contemporary romance novel; while Larry McMurtry and Louis L’Amour are primarily bestselling western writers and Elmore Leonard and Sue Grafton are detective brands.

The marketing of an author as a brand includes the occasional purchase of relatively inexpensive 30-second local market spots on television, using the author’s story line as a mini-movie. On occasion, a simple voiceover on a still frame of the book cover with some tantalizing copy, a few reviewers raves, and a reference to other successful books from the same author can build a groundswell.

Cable TV advertising allows for more direct, targeted access to the audience for a given genre. It is relatively inexpensive to reach the perfect female audience with Lifetime, the Food Network, and WE. The male audience is available through ESPN, CNBC, or the local transmission of any major sports event.

The branding approach is not foolproof, however. As with any product, after an audience has been groomed to a brand’s particular attributes, those attributes cannot be toyed with. In the case of publishing, authors occasionally write in several genres, either under pen names (pseudonyms) or using their own names. Ed McBain, author of the 87th Precinct novels, also has separate literary reputations under his real name, Evan Hunter, as well as Curt Cannon, Hunt Collins, Ezra Hannon, and Richard Marsten.

The most important objective is to avoid “unselling a brand” by confusing the fan of one author/genre with other works by the same author in another vein.

Branding the Character

Many fictional characters have served as stars of entertainment content—Snow White, Winnie-the-Pooh—but most of these have become star brands over long periods of time, moving from the page to the screen as entertainment sectors found that the content they represented could be stretched into other profitable areas. However, few characters represent the modern-day approach to the whole of entertainment marketing—books, film, licensing—as well as a certain young wizard with a lightning bolt scar on his forehead.

Case in Point: Harry Potter

On a train trip from her small village in the countryside of England to London, a single, unemployed mother began to daydream about a young boy with big eyes, round glasses, a very high IQ, a quirky sense of humor, and the ability to use magical powers to make exciting things happen. With the launch of J.K. Rowling’s first book, a paradigm shift occurred in children’s book publishing. Harry Potter was truly magical.

Rowling was rejected by 12 publishers before Bloomsbury, a small U.K. publishing house, secured the first rights to the first novel. Barely realizing what it had in its hand, they offered the U.S. and worldwide rights to Scholastic, Inc., the leading global children’s book and educational materials (newsletters, classroom newspapers, textbooks, early readers, and video and audio tapes) publisher, including stakes in some highly acclaimed children’s theatrical and home video films. Scholastic snatched up the rights for $105,000.

Though typical hardback or trade format fiction books sell under 200,000 copies, blockbusters (Clancy, Turow, Sheldon, Collins, Fleming, Le Carre, and so on) sell close to a million copies or slightly more. Harry Potter hardbound books one through four sold in excess of three million copies each. Young Mr. Potter has repeated or exceeded those numbers in the paperback versions. A focus on the contributions of great marketing explains why and how this happened.

First, as soon as the book went into circulation among the literary agents and those knowledgeable about children’s publishing, the marketing machine was set to work. An all-points alert went out to every possible promotional opportunity available, including global talk shows and interviews with the still-dazed-but-delighted Ms. Rowling.

Second, the popularity—as built through marketing efforts—of the brand reached a near frenzy with the publication of book four. Demand was built by artificially limiting the supply for a sold out or possibly unattainable product. This created an atmosphere of “must have.” The launch date was a preannounced event, and the books were rationed by geographic area and store location, thus putting into place a master marketing tactic. The need—or perceived need—for advance orders or prepaid reservations for the book was trumpeted with stories in national consumer, business, and trade press, including Time, Variety, Publisher’s Weekly, and a cover story in Newsweek. Seemingly overnight, Harry Potter became a brand in the same children’s book solar system as Dr. Seuss, Maurice Sendak, and even classics like the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew.

The third marketing hurricane was the decision by Warner Bros. studio to option the book for a film and start a global search for the young actor to play Harry Potter. Meanwhile, the studio’s licensing, merchandising, and sponsorship magicians went to work. They strove to make the Potter character a marketing icon that would shake Disney’s ownership of the licensing marketing crown and provide a true battle for domination of the children’s entertainment sector.

In the end, Harry Potter won the battle with Voldemort and made J.K. Rowling a very wealthy woman. But even more important, Harry cast a spell on young children, turning them into readers at a time when publishers worried about whether the next generation would ever break away from television.

The Changing Publishing Environment

Publishing has been in the spin cycle for well over a decade, buffeted by the digital disruption and a shift in the public’s reading habits. As mentioned previously, the advent of Harry Potter was a golden moment for the publishing business, creating new readers in the younger age groups—a hopeful sign for the future, given the falling numbers of adult readers.

Consider the statistics from the Association of American Publishers in Exhibit 7-3.

Do take notice of the increase in audiobook sales, as mentioned previously—another sign of the digital disruption.

This slide in sales has traveled downstream, creating an equally difficult time for distributors. The giant Borders chain disappeared altogether, and last-giant-standing Barnes and Noble posted declining sales in both bricks and mortar and their digital device (the Nook reader) sales in 2012.

Independents still struggle, with many shuttered over the last decade and many more struggling to hold on. The math is simple. Trade books are sold with what is known as a long discount. That means wholesalers and major retailers demand 50%, 55%, and even 60% discounts to handle trade books. Most independent bookstores must buy their books from major wholesalers, like Ingrams and Baker & Taylor, and the discount the independent stores see is less than if they bought direct. But it is not discounts that killed the independent; it was the inability of independents to put enough books into their bookstores (too little cash flow, no access to large capital markets) and their linked inability to discount to the customer—along with what was often a 1960s temperament about business and business management.

The old “gentleman’s game” of the publishing world—brandy and tea in the conference room, tweed jackets with patches on the elbows, risk-taking with unknown authors—is either long gone or barely breathing. It’s been replaced by merger mania and the gimlet eye of the media mogul. In the late 2000s, Penguin merged with Putnam, Random House combined with Bantam Doubleday Dell, and HarperCollins took over Morrow and Avon. Now Random House is in discussion with Pearson for a merger with Penguin. Penguin Random House will become the world’s largest trade book publisher.

Will it mean better books? More bestsellers?

Publishing has never been about homeruns. It is truly a bunt/singles/doubles world, with the occasional big blow bringing big dollars to the lucky imprint. Creating bigger and bigger publishing houses will not guarantee more bestsellers—editors and agents can only find and vet so many books at a time. When corporate giants go looking for cost cutting, it’s payroll that always leads the way. Can any publisher create more books with less of the front-end skills? Can publishing survive by cutting out midlist sales? What good does more economical distribution do if there’s less quality product?

The money people point to the rise of Amazon and say that mergers must happen, that economies of scale are the only hope for the industry. The rise of Amazon has grabbed profit margins by the throat, creating new price points that hover at $9.99. If digital sales continue to rise, it means more books sell—but at fewer dollars.

Worst of all, shuttering stores shuts down the single-best mode of discovery for any book. So, if there was ever a time when savvy marketing was needed in this industry, it’s now.

Small Publishers in the Mix

While big publishers get bigger and big bookstore chains stutter-step, there are still a number of small publishers and small, independent bookstores fighting the good fight. Several small press magazines—both print and digital—and the Small Publishers Association of North America (SPAN) serve the growing number of small publishers, which includes traditional imprints, university presses, and newer imprints that have surged to fill the niches left uncovered by publishers grown too big to sign marginal or midlist titles.

In fact, given the tightening focus of major publishers, many niches are left open as new frontiers for entrepreneurial publishers with start-up companies. Whether it is the intention of these companies to rise to become major forces themselves or to merely create enough of a presence to tempt the acquisitions unit of a major house remains to be seen. But, for many, the opportunity to grow in a robust market is aided by digital technology.

Global Reach

International sales account for as much as 40% of most good publishers’ income. Additionally, the growth of e-tailing (which accounts for as much as 30% of most publishers’ domestic income) has forced global pricing into the book business. No longer is a book published in the U.S. at $30 and sold in Europe at $90; the Internet has leveled pricing. Check out Exhibit 7-4 to see where the world’s top publishing companies are based.

Summary: Books

Another battlefield in the digital disruption, book publishing continues to morph into a new business model. Still the gatekeeper of story, books continue to create great starting points for many other forms of media, including movies, television, and Broadway shows. This synergy helps create continuing sales by opening doors to new consumers unfamiliar with the original work. The impact of digital publishing, e-readers, and the distribution giant Amazon—now a publisher itself—continues to play out, forming the impetus for continued mergers and acquisitions. Marketing professionals can find great opportunities in this platform but will need to be nimble as the industry changes.

Newspapers and Magazines

For the purposes of our discussion regarding entertainment marketing, we include the following commentary on newspapers and magazines as it relates to their role as a marketing platform. Entertainment vehicles of all types still rely on these traditional print models, whether for reviews or for advertising. However, we urge you to dig deeper on the subject of traditional print and the challenges it faces. There is much to be learned about consumer behavior in doing so.

Newspapers

When it comes to print publication and the decline in traditional business models, newspapers are the niche most under assault today. The decline in readership has as much to do with shifts in consumer lifestyles—more interest in broadcast media, viewable on smartphones and tablets—as it does with the speed of information delivery. Let’s face it: News coverage happens faster when it can be broadcast directly, skipping the time-consuming steps of printing and distribution. Ours is a faster-paced society, and print has a hard time keeping up.

Unfortunately, speed often means less time spent on fact-checking and objectivity, but in an age of “citizen journalists,” the entire news-gathering/dissemination business is in a whirlpool. Reader beware.

Early on, many papers, struggling with the leap to the digital age, simply posted content online for free, hoping to attract enough eyeballs to create better advertising revenue. Though the readers did come, the dollars didn’t—at least, not enough dollars to make up for the loss of the print ad revenue.

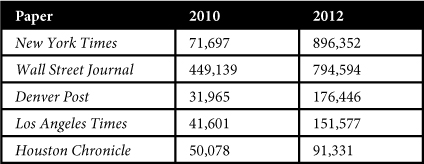

What appears to be a turning point occurred in March 2011, when The New York Times announced a metered system for charging for the digital version of the paper. Although it is still possible to download articles for free, the Times limits the number within a given time period. The Old Grey Lady, as she is affectionately known (even though she is no longer grey, bowing to color in the 1990s), has once again proven her popularity, reporting more than 560,000 paying digital customers.16 The additional good news here? Print subscriptions have held their value, as they allow for free digital access. Ads can be seen—and sold—in both formats. Though it remains to be seen how newspapers will weather this very dire turbulence, digital growth is occurring across the country as demonstrated in Exhibit 7-5.17

16 Rieder, Rem, “Get Ready to Pay for Online News,” USA Today, January 22, 2013.

17 2010 data: Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism, The State of the News Media 2011. 2012 data: “Circulation Numbers for the 25 Largest Newspapers,” Denver Post, October 30, 2012.

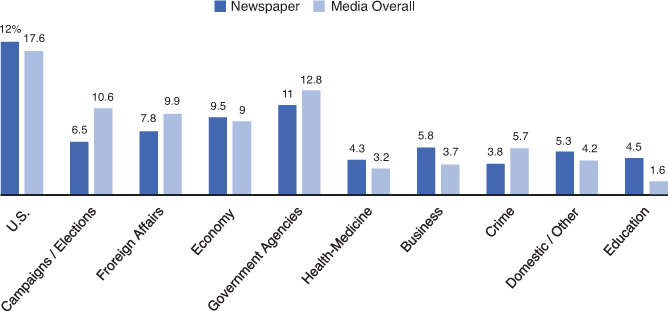

Newspapers continue to be a viable entertainment marketing platform, with wide reach into important demographic segments, and are still a source for local information. Consider the data in Exhibit 7-6 and notice how, while broad, general interest issues such as elections and disasters are the key storylines for other media, newspapers still excel at reaching readers who are interested in subjects that hit them close to home: business, lifestyle, health, education, and economy.

Exhibit 7-6 Newspaper topics differ from media overall

Source: Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism, The State of the News Media 2012

Magazines

As with newspapers, magazines have been buffeted about in the digital storm. The difference is, this platform seems to be finding stable ground faster than its newspaper cousins. Newspapers, by and large, are vehicles for news coverage, published daily and focused on specific events and trends. Magazines, on the other hand, focus more on feature-length writing, diving deeper into the subject matter, and are designed for specific niches. If media executives could determine by demographics, geography, occupation, or any of the other determinants of special interest that demand for a magazine on underwater basket weaving existed, you can bet one would be woven right into the fabric of the market.

Even in this day of disruption, magazines—both print and online—continue to grow in popularity. Ten years ago, we reported that there were over 20,000 magazine titles in circulation. Data published by the Association of Magazine Media18 shows that as of 2010, there were over 24,700 magazines being published, addressing 280 different categories, from accounting (55 magazines) to zoology (12), with stops in between at baseball (58), energy (50), oil and fats (6), and unidentified flying objects (3). More to our subject, there are 171 entertainment magazines, 88 publications for fans of movies, TV, and radio, and 96 that focus on film.

18 “1998–2010 Number of Magazines by Category,” the Association of Magazine Media at www.magazine.org.

Of all these, approximately 160 magazines account for 85% of the revenue generated by this industry. The names of the companies generating the most revenue from magazines include Time Warner, Hearst Corporation, Reed Elsevier, Advance Publications, International Data Group, Thomson Corp, Ziff Davis Publishing, Reader’s Digest Association, News Corp, and Meredith Corporation. Among the giant media companies mentioned earlier in the book, Capital Cities/ABC, Tele-Communications, Inc., CBS, Inc., Gannett Co., General Electric Co., New York Times Co., Viacom, Knight-Ridder, Cox Enterprises, and Turner Broadcasting all have stakes in the magazine industry.

Off the Page and Into the Ether

Many of these magazines have migrated to the Web, where they offer subscribers (and readers, if they aren’t charging) an interactive experience that binds reader and magazine even tighter than before, with clickthroughs to advertisers websites, special offers, and social networking to compare notes with others like themselves.

Growth isn’t limited to the Web. Revenue continue to be aided by impulse purchases at drug stores, book stores, and airport concessions. Many magazines have extended their brands into television and vice versa. Consider National Geographic and the National Geographic Channel; The Discovery Channel and Discovery Channel Magazine, ESPN and ESPN The Magazine. Magazines create content for television, and television creates content for magazines. It’s a great relationship for the consumer and a great marketing platform for reaching specific interest groups.

Magazines can also thank the explosion of tablets and other mobile devices for this growing popularity, although that golden goose does produce some challenging eggs. Every new platform requires a new investment in staff and software, all to keep up with the changing needs/wants of the consumer. But digital devices are a great boon to magazines. Pew Research reports that as of December 2012, 45% of American adults had a smartphone. As of January 2013, 26% of American adults owned an e-book reader, and 31% owned a tablet computer.19 Even more important, the Association of Magazine Media also found high levels of engagement with tablet publications. According to their research, 70% of readers want the ability to purchase products and services directly from electronic magazines. 73% read/tap on advertisements appearing in electronic magazines, and 86% access the same electronic magazine issue two or more times.20

19 www.pewinternet.org/Trend-Data-(Adults)/Device-Ownership.aspx

20 “Magazine Media Factbook, 2012–2013”, www.magazine.org/sites/default/files/factbook-2012.pdf

The magazine platform is an area where brand supremacy is finding interesting challenges. Consider Better Homes and Gardens (BH&G), for years a leader in the home/lifestyle segment, a well-established brand that millions of women (and men) have turned to for advice on cooking, home design, and home style advice. The advent of the digital magazine has brought such newcomers as Houzz.com, a cross between a social networking site for home renovation enthusiasts and a tremendous home design resource, with literally millions of photographs, searchable by style, function, and form—in all combinations. Want a hundred ideas for a corner fireplace in a contemporary home? Or a thousand thoughts about front entrances for a traditional place? It’s all there, and more, at your fingertips, in a constantly growing database.

We use this example to demonstrate the rising development of online magazines that allow the readers to create the content, while the online editorial staff adds short features that engender conversation. Quite different from the old days, where editorial content was served to the reader monthly in a format determined by a hopefully far-sighted staff.

Magazines still appear to be the Little Engine That Could—or at least, wants to be. Far from disappearing, new magazine launches happen yearly. In the first quarter of 2012, 52 new magazines appeared. The top category was “restaurants,” with five new DiningOut guides from Pearl Publishing. The other top categories for new launches were “hunting & fishing,” with four new titles from J.F. Griffin Publishing, and “lifestyle,” with four new magazines, including Bloomberg Pursuits. There were 12 magazines that folded in that same time span.21

21 “Magazine Launches Outpace Closures in First Quarter of 2012,” PRWeb, April, 2012. www.prweb.com/releases/2012/4/prweb9361089.htm

Like every other platform under attack from the disruption, the future is still a long way off; much will happen before it all settles out. But when it comes to magazines, there’s a moral to the story: Next time you think magazines may be dying, don’t. Just because you’re not interested in a subject doesn’t mean a whole lot of other people aren’t. Just like you, they want their own little media home, be it online, in print, or cross-platformed with a cable station. And if you want to reach them, magazines offer a great way to do that.

Summary: Newspapers and Magazines

Newspapers continue to battle with changing technology, with many folding and most dealing with ongoing staff layoffs. The tide could be turning now that there is more acceptance of paid content, but that change is still underway. Magazines continue to be the leader in niche marketing opportunities in regard to the entertainment sector of publishing. With an estimated 24,000+ titles in the marketplace, there are few audiences that cannot be reached via this medium. Furthermore, the expansion of magazines onto the Internet and mobile devices will continue to offer opportunities to reach an even wider audience.

Summary: Publishing

Publishing, like all other platforms, has felt the brunt of digital disruption. Publishing houses continue to merge and contract. E-books and digital devices are causing inroads into revenue but appear to be leveling off as the market becomes saturated. Bookstores are under assault by online distribution, specifically Amazon, who is now also acting as a publisher, while self-publishing continues to grow.

Although newspapers have contracted sharply, the ability to charge for online versions appears to be finding a foothold. Magazines continue to grow in number, offering both print and online versions to what seems to be an ever-increasing variety of niche markets.

For Further Reading

Books

Davis, Gill, and Richard Balkwill, The Professionals’ Guide to Publishing: A Practical Introduction to the Working in the Publishing Industry, Kogan Page, 2011.

Forsyth, Patrick, and Robert Birn, Marketing in Publishing, Rutledge, 1997.

Grecco, Albert N., The Book Publishing Industry, Allyn & Bacon, 1996.

Kleper, Michael, The Handbook of Digital Publishing, Pearson, 2000.

Picard, Robert G., and Jeffrey H. Brody, The Newspaper Publishing Industry, Allyn & Bacon, 1996.

Thompson, John B., Merchants of Culture: The Publishing Business in the Twenty-First Century, Polity Press, 2012.

Other Resources

Gale Directory of Publications & Broadcast Media (published each year by Gale Research).

LMP: Literary Market Place: The Directory of the American Book Publishing Industry (published each year by Bowker).

Publishers, Distributors & Wholesalers of the United States (published each year by Bowker).

Ulrich’s International Periodicals Directory (published each year by Bowker).