9. The Universal Language: Music

Music is an industry that has been under digital assault for well over a decade: This platform struggles with the near-disappearance of its original business model, paradigm shifts in consumer’s buying decisions, and a culture that seems to have less regard for the creator’s—and publisher’s—need to make a living.

In this chapter, we investigate the conditions that face music marketing professionals in the era of disruption: the shift to digital downloads, piracy, and a disturbing trend toward not owning music.

It’s a complex business and still an important platform.

They’re Playing Our Song

Music transcends borders, ignores rivalries, has no knowledge of political persuasions. At its best, music can create joy, heal pain, move us to tears, or stimulate a desire to reach further than we ever thought possible. Music is the one language that links all of us, no matter the age, gender, race, or politics of the listener. It is the one universal form of communication.

It is a whopper of a business, one that reaches billions worldwide.

It is also a business that struggles with new technologies. Though it is difficult to put absolutes on dollar figures—the music business is notoriously private—estimates show that the industry’s revenue on recorded music have sustained a stunning hit in the last 10 years—and not the kind this business is usually looking for. Consider the data in Exhibit 9-1.

That’s a nearly 50% cut in revenue. Does this mean that people have stopped listening to music? No—but they’ve certainly slowed down buying it. When that happens, it has an impact on all sectors of the industry, but especially on any form of property.

The Three Forms of Property

Going back to our original discussion of copyright and content, the music business focuses on three types of properties that can be monetized: publishing (compositions), recording, and media (CDs, MP3s). Each part of the industry has its own ecosystem.

Publishing

Songwriters or composers might or might not record their own songs and might or might not own their work, depending on how the work was created and for whom. For instance, a composer working on a Disney animated film is most likely working under a “work for hire” contract, which means Disney actually owns the song and the rights to sell it. On the other hand, an independent songwriter like Beth Nielsen Chapman might have her song recorded by Faith Hill. Chapman most likely assigned some of her rights to a publishing company, who will collect publishing royalties from Hill and pay a portion to Chapman.

Though publishing is an essential partner to the recording sector of the music industry, there are publishing companies that focus on nothing but placing music in television and movies, with little concern for releasing any recordings on an individual basis. The demand for music in other forms of media—movies, television, games—is high; publishing benefits from this demand.

Recording

When most lay people speak of the music industry, this is the segment they are referring to: the part of the business that consists of recording artists, record producers, recording studios, and the distribution of recordings, whether in physical form, over the airwaves, or downloaded digitally.

This is an area that has seen huge change in the last decade. Where developing an album (remember those?) once demanded a cadre of professionals—audio engineers, studio space, studio musicians, ranks of full-time publicists and marketing professionals, today’s professional musician is every bit as likely to be recording his or her work in a home studio, thanks to huge leaps forward in software. The actual marketing of that music still depends on professionals, but they might be freelancers, brought in on each individual project. We look at this more closely in a minute.

Media

At one time, the physical distribution of media on CDs was a huge part of the business, with big box retailers such as Virgin Records or Tower Records reigning supreme as the buying hubs. The advent of digital downloads has relegated those two companies to the dustbin, while online retailers such as iTunes or Amazon now service the market. This is the segment of the market most likely to feel the next hit in the shifting business of music. After all, if you can stream your favorite music anytime and anywhere, why do you actually need to own a recording?

Make no mistake: CDs are still being sold, and we discuss this more when we talk about the changes in distribution. For now, let’s stay focused on the business at large.

Major Players

The U.S. music market is split between three major players—Universal Music Group, Warner Music Group, and Sony Music Entertainment—and a large group of independents. Exhibit 9-2, current to the end of 2012, does not reflect the year-end sale of EMI to Universal Music Group. That deal was approved in late 2012 in both the U.S. and Europe.1

1 “Universal’s Purchase of EMI Gets Thumbs Up in U.S. and Europe,” NPR, September 12, 2012, www.npr.org/blogs/therecord/2012/09/21/161560048/universals-purchase-of-emi-gets-thumbs-up-in-u-s-and-europe.

2 The Nielsen Company & Billboard’s 2012 Music Industry Report.

Each of the major labels often have its own publishing, recording, and media divisions. The independents might be more focused on the recording sector.

Music is a hit-driven business, pure and simple—the more hits, the more money. But it takes a lot of releases to make a hit. Over 11,000 nonclassical albums are released by the major labels every year, but now in the day of the individual download, it is unusual for more than 120 of those albums to sell more than 500,000 units (a “gold” record) in a physical format.3 The major labels generate a high number of these hit releases, using both in-house and freelance talent to create, distribute, and promote the work—and they must, for it’s the winners that cover the cost of releasing the losers.

3 Vogel, Harold L., “Entertainment Industry Economics: a Guide for Financial Analysis,” Eighth Edition, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Independents

During the last century, heavy consolidation in the industry resulted in many independent labels springing up. These labels joined forces with a few disenfranchised or new talents, using sales at concerts and free performances—or over the Internet—to cover the costs of their startups as they struggled to create the next important mini-label.

Today, independents as a whole are far from being small potatoes. Independent labels (as a group) generally have the largest share of prerecorded industry sales promoted by Sound Scan and released by NARM (National Association of Recording Manufacturers). These sales can represent anything from a garage band making its own limited release for companies like Rhino Records, TVT, and others who generate $50 to $100 million in sales. Many of these larger independents give the artist greater creative freedom and a greater share of the total revenue pie, including tour receipts, licensing, and merchandise.

Private Labels

With the rising availability of excellent recording software, today more than ever there is room in the music industry for the self-promoter. Ever since the early days of recording, there have always been those pioneering souls who had a 45 pressed or a CD burned, threw them in the car, and made the rounds of the radio stations. Liz Phair originally got her start releasing audio cassettes under her own label Girly Sound before signing with Matador. More recently, Justin Bieber put his videos on YouTube before being discovered by Scooter Braun, who went on to become his manager.

Today’s budding artist can record a song or an album and throw it up on the Web, either in the form of a download or as a video posted on YouTube. But as with all other forms of entertainment media making its way to the Web—or to mobile devices—it takes more than simply hoping someone will notice. The entertainment marketing ecosystem is alive and well and ever-growing, servicing the hopes and dreams of those who would be stars.

Building momentum is difficult in a day when tens of thousands of new releases are shouting for attention. Advertising budgets, a full-time publicist, and a major tour manager are not part of most indies’ experiences. Regardless of the accessibility of the Internet, it still takes a team to get you on top.

Let’s take a look at the more established path to listeners.

The Music Development Process

As in every sector of the entertainment industry, each music career has its path. In a world where people believe they can make it big by posting a video to YouTube, in Major-Label-World, the typical trip to the top still looks like this:

An aspiring singer/songwriter

![]() Writes a few hot songs for a hot genre, forms a band or works solo, and builds a loyal fan base at music clubs and festivals.

Writes a few hot songs for a hot genre, forms a band or works solo, and builds a loyal fan base at music clubs and festivals.

![]() Hires a manager and/or producer.

Hires a manager and/or producer.

![]() Makes a basic demo and sends it to music labels and scouts; they might hire a freelance public relations (PR) person.

Makes a basic demo and sends it to music labels and scouts; they might hire a freelance public relations (PR) person.

![]() An A&R (Artist & Repertoire) professional hears the demo, likes it, makes a recommendation to produce a quality CD, and puts the act in front of a music label executive with decision-making authority.

An A&R (Artist & Repertoire) professional hears the demo, likes it, makes a recommendation to produce a quality CD, and puts the act in front of a music label executive with decision-making authority.

![]() A senior executive at the label agrees to go forward, most likely in a demo deal, short for “let’s see what you’ve got and how they respond.” A budget is developed for the project.

A senior executive at the label agrees to go forward, most likely in a demo deal, short for “let’s see what you’ve got and how they respond.” A budget is developed for the project.

![]() The label either hires or uses staff engineers, studios, back-up artists, songwriters, and an in-house producer to polish the work.

The label either hires or uses staff engineers, studios, back-up artists, songwriters, and an in-house producer to polish the work.

![]() A CD is mastered, and a major marketing push is developed.

A CD is mastered, and a major marketing push is developed.

![]() A publicist arranges talk shows, a tour manager books major concerts, magazine covers are planned, national radio play is organized. In the past, a music video might have been made, but tighter budgets have removed this from most deals.4

A publicist arranges talk shows, a tour manager books major concerts, magazine covers are planned, national radio play is organized. In the past, a music video might have been made, but tighter budgets have removed this from most deals.4

4 With the changing role of MTV—the network is now the home of reality shows, not music videos—the video-as-promotion has taken a deep slide in popularity. Thus does what was once a rock phenomenon become, literally, a footnote in music history.

![]() Shipments go to wholesalers or to digital distributors, retailers are sent details on marketing push, and a media and publicity campaign is implemented.

Shipments go to wholesalers or to digital distributors, retailers are sent details on marketing push, and a media and publicity campaign is implemented.

From that point on, only the market will tell if the artist at the eye of this storm will be a one-hit wonder, a major superstar, or a comfortable career-type. Regardless of the star’s status, he or she will become intimately familiar with the ways of the business—starting with the importance of intellectual property (IP).

The Rights Stuff

Once again, in the beginning, there is C: content. As in every other sector of entertainment, music content must be protected carefully. The music industry was one of the first to recognize the need for organizations that protected the IP rights of artists, as much (if not more) to protect the potential revenue due the recording company, as for the artist.

Two early pieces of legislation influenced the decision to create organizations that would protect these rights. In 1897, the U.S. granted performance rights to authors of nondramatic musical works (prior to this time, the performance had to be for profit), but an author of a musical work was hard-pressed to check up on every performance of his or her output. This was the rationale behind the 1914 formation of the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP). The belief was that the author’s rights could be protected better collectively. ASCAP became increasingly more powerful in the U.S. until 1939, when radio broadcasters, unhappy with ASCAP’s monopoly, formed their own organization: Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI). BMI has become the other major performing rights association in the U.S., also representing composers, publishers, and songwriters.

ASCAP and BMI employ a blanket license, granted for a given period, which permits various institutions to perform any work in their repertoire. They then distribute royalties to members based on the popularity of their works. This allows the author to avoid handling each infringement of the copyright on an individual basis—a tremendous cost savings to the artist. It does, however, mean that these organizations must closely police the use of the works.

This became increasingly difficult as digital downloads became the standard of the industry. Certain moves by the U.S. government didn’t help the problem. In the early part of this century, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) led an effort to change the U.S. copyright law that designated sound recordings as “works for hire.” This controversy began with language in the 1999 Satellite Home Viewer Improvement Act that might have prevented artists from reclaiming ownership of their master recordings. The RIAA worked with the Artist’s Coalition (led by Don Henley, at that time formerly of the Eagles—they have since regrouped), the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS), the American Federation of Musicians (AF of M), the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (AFTRA), and the Music Managers Forum to create language that would have a long-term effect on the future IP rights of musicians.

Additional efforts in the last decade have included work with international organizations such as BUMA (Holland), GEMA (Germany), SACEM (France), and the Performing Rights Society (PRS, UK) on an International Joint Music Venture (IMJV) aimed at heading off music IP issues brought on by the globalization of the music marketplace and the move to digital downloads.

The 360 Deal

Legal ownership of rights is the heart of monetization. The biggest change in rights over the last decade came through the institution of what are known as 360 deals, in which the artist signs away a portion of the rights to everything connected with the work, including the traditional revenue-generating pieces—individual downloads or CDs—along with tour revenues, T-shirt sales, any appearance in a motion picture, the ownership of the website—in short, anything that adds to the revenue stream.

The philosophy behind this is based in brand-building. Because everything the label invests in—or even if it doesn’t; even if it’s something created by the artist to promote the work—is part of building the artist’s brand, the label wants to share in the revenue from all of those sources.

More than one artist has looked at a 360 deal and decided to look elsewhere, but it’s hard to walk away from the potential payoff of a major label’s efforts.

The Changing Face of Distribution

The digital sale of music topped the physical sale in late 2011. As reported by CNNMoney,5 based on reports from Nielsen and Billboard, digital music purchases accounted for 50.3% of music sales in 2011, with digital sales up 8.4% from the previous year and physical album sales declining 5%. That’s still a lot of plastic being pressed—it’s not time to turn the blank CDs into coasters—but it does speak to the future.

5 “Digital Music Sales Top Physical Sales,” CNNMoneyTech, January 5, 2012.

Digital downloads found their first foothold in Napster, which was shut down after protracted copyright infringement battles with the U.S. government. Napster returned as a digital retailer but was eventually bought out by Rhapsody, a music subscription service. Apple filled the gap with the now-giant iTunes, allowing users to purchase downloads but limiting them to the number of devices that could receive those downloads.

This rise in digital downloads cut the legs off any number of traditional retailers. The big box stores, as mentioned, disappeared. Columbia House, once a large buy-by-mail club, threw in the towel and focused on movies and books. Though you can still order a CD from amazon.com or buy one at Target or maybe find a few oldie compilations at Costco or Sam’s Club, the hard disk is quickly becoming a small dot in the rearview mirror of the music business.

The trend to digital download continued on into 2012 but was joined by another force in the disruption: the rise of streaming versus downloads. As fast as individual downloads gobbled the market, we now have the rise of subscription services—Rhapsody and Spotify—that allow listeners to listen to music for a low monthly price with no individual download fees. Listeners are not buying the music; they are simply listening to it, whenever and wherever they want. And with the ever-growing rise in the ownership of mobile devices, the market for subscription services seems nearly unstoppable, especially when these subscription services allow you to download music (so that you can listen even when you’re offline) as long as you’re a member.

This is all based on the tsunami of tablets and smartphones, which are convenient and portable. As we said before, why own music when you can get it almost anytime you want it?

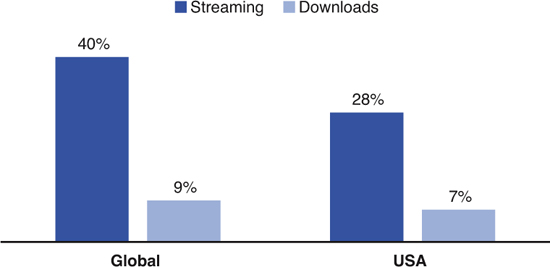

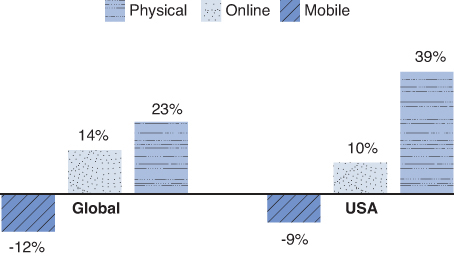

This shift to streaming is a global phenomenon. Consider the data in Exhibits 9-3 and 9-4.

Source: Strategy Analytics Global Recorded Music Forecast 2012

Exhibit 9-4 The rise in mobile music revenue

And note the impact of mobile streaming versus digital.

But with the rise in digital distribution—whether downloaded or streamed—has come a concurrent rise in piracy.

The Black Flag of Piracy

From the street corners of Manhattan, to the alleys of Hollywood, the back-street stalls of Beijing, and the beautifully appointed department stores of Sao Paulo, counterfeit CDs are still carefully reproduced, artfully packaged, and sold at greatly reduced prices—with no revenue going to either the original music labels or the artists. Now with digital downloads taking over distribution, the challenge has become even greater. There is far less cost for pirates to steal or allow for the distribution of downloads than in creating a CD.

The lack of global IP protection or copyright enforcement in many countries around the world has resulted in the loss of billions of dollars to the music industry. This situation is improving but is still not perfect.

We prefer to not give the pirates any publicity by naming their sites, but in general, the biggest threats came from sites that allowed listeners to share their own libraries by uploading content to the master site, then share it with whomever wanted to download it. Certain pirates claimed that they could not be held accountable for what subscribers did once the content was posted and even went so far as to encrypt the sites so that the site owner could legally claim that they didn’t know what was stored there. The battle over this copyright infringement rages on.

In short, if you’re downloading content from the Internet without paying a fee for it—be it per download or via subscription—you’re stealing, plain and simple. Although you may never be caught, we hope that you ask yourselves how you might feel should someone walk into your apartment, dorm room, or home and simply walk out with whatever you value the most.

“Free” is not a word that works in the entertainment economy. If you’re serious about making a living in it, make sure you respect the hard work of others.

Reaching the Masses

Regardless of how listeners eventually purchase or subscribe to a song, they still need to hear it somewhere first. Though social networking sites and subscription sharing services are certainly part of this discovery process, the long reach of radio still provides an initial boost to most new music.

The All-Important Airplay

Part of the standard promotion for any group or individual’s success is getting airplay on radio stations. This poses a variety of challenges, as radio is an advertising-driven medium. Stations want to play the songs that are most likely to attract listeners to their format, the playlist of which has been carefully mapped out to grab the particular demographics advertisers are after.

To get airtime, the label’s promoter must first get the new singles and albums in the hands of the appropriate stations. Advertising budgets can help in this regard; a mega-budget often signals to station programmers that a song can merit more playtime to the benefit of a station and its advertising.

However, there is more to getting airplay than just demographics and advertisers. Radio revenue is also dependent on independent promoters, the people who act as middlemen between record labels and radio stations. These indies offer a variety of payments to the stations to play certain songs—for instance, cash and promotional items—with the money to pay for such enticements coming from the record labels themselves.

These payments are not to be confused with “payola”—the term that grew out of the scandals that wracked the radio world in the 1950s, when disc jockeys (DJs) like Alan Freed were found to have received payments to play certain songs. Payola is only illegal when the listener is not made aware that payments are being made. The fact that indies are bona-fide businesspeople providing a “service” to the industry—up-front—keeps the practice from falling to the wrong side of the law.

Fredric Dannen’s book, Hit Men: Power Brokers & Fast Money Inside the Music Business,6 offers an intriguing insight into the practices—good and bad—of the music promotion business. As described in Hit Men, in the early days, the enforcers or distributors—financially supported and acknowledged by the labels—would buy “radio play” from DJs at radio stations all across the country with cash, drugs, and sex. When charges of racketeering and corrupt practices were brought against individuals at the labels and radio stations, the business cleaned itself up. Legitimate businesses were created under formal contract, with the labels to maintain constant contact with the radio stations, studio managers, DJs, and program directors, using full-blown marketing kits and promotional items to gain airtime. These practices include legitimate agreements to promote co-op advertising dollars to gain strong airplay support.

6 Dannen, Fredric, Hit Men: Power Brokers & Fast Money Inside the Music Business (New York, NY: Vintage, 1991).

But what about the public, you might ask, and their desire to hear certain songs? Certainly those “request lines” lighting up must have some impact on airtime? The answer: maybe yes, maybe no.

The Bogus Request Scam

In the 1990s, country music radio stations in particular were plagued with floods of requests programmers soon began to suspect weren’t genuine.7 The calls came in clusters; hip DJs soon identified several specific labels they felt were responsible for hiring agencies to make bogus calls. This sort of promotion, unethical and as much a possible source of harm to performers as a help, began again in the new millennium, but radio stations are quicker to spot the patterns.

7 Stark, Phyllis, “Bogus Request Calls Hit Country Stations,” Billboard, April 22, 2000.

Because station programmers may skew their mix based on requests, a motive might have been to ensure more hits for a label’s products. Some stations retaliate by boycotting all products from these suspicious labels. Record labels are quick to deny the allegations, often claiming over-zealous fans. Radio stations, however, ultimately distrust labels associated with the practice, and a resulting diminished skew can result. This practice is much more difficult to perpetuate with Internet-generated station requests because email or text requests may be more readily screened.

Though it can be difficult to identify “real” listeners over the airwaves, it certainly isn’t difficult to do at the heart of the music experience: the live performance.

Live Music

Live music happens in venues across America: Madison Square Garden in New York City, blues bars in San Francisco, the Newport Jazz Festival, honky-tonk dance ballrooms in Oklahoma, stadiums, outdoor amphitheaters, beach boardwalks, bandshells, open-air plazas, and, of late, in boites—New York/Paris-style cafes. Examples include the Carlyle in New York, where Bobby Short reigned for decades. Since his death, the Carlyle has filled the room with random, high-profile acts.

Although some prefer to listen to music in intimate settings where they can actually see the artist, others crave the experience of being surrounded by thousands of other rabid fans.

The modern-day P.T. Barnum who brings the circus to town knows how to build interest, anticipation, and deliver a fanfare. The three rings in this particular case are the act or acts (think Lollapalooza or Lilith Fair, which is rumored to be starting up again), the associated retail sales of T-shirts, CDs, and full-color programs packed with photos, and the sponsorship dollars built on synergy with brands anxious to bring their messages to the artist’s audience. These revenue streams enable the producer/promoter to gain a return on the significant investment necessary to stage these modern-day spectaculars. The promoter’s marketing program will utilize local newspapers, local spot television, and heavy promotional radio featuring ticket giveaways to call-ins from listeners.

However, live music presentations have become more and more expensive due to many factors: the cost of venue rentals, housing for talent, equipment, special-effects, laser shows, special lighting, and large-screen projection. It has become essential to locate sponsors who can fund the bulk of the expense. Kool cigarettes became the founding sponsor of the Kool Jazz Concerts in New York and Newport, while Budweiser, Pepsi, and Coca-Cola all support warm–weather, outdoor concerts and provide seed money as well as outright sponsorship funds, balanced by obtaining exclusive pouring rights (the only brand of beverage poured at the event).

Hundreds of these sponsored events go on around the U.S. every year, including large-scale music-oriented events, like SXSW in Austin, Texas, or Summerfest in Milwaukee. They drive sales for both the artist and the sponsor and give live music fans a chance to feed their craving.

However, nothing gives the true live concert fan an experience like the “big top” of the music world: the megatour.

Megatours

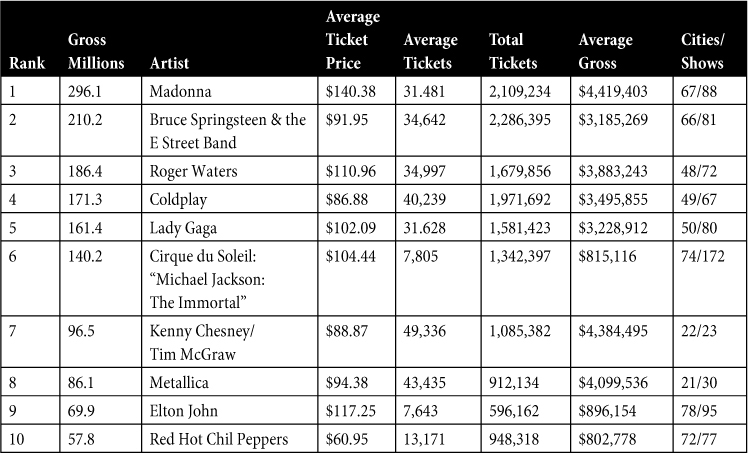

There are many megatours each year, bringing groups and artists like Madonna, Coldplay, Jennifer Lopez, Lady Gaga, or Bruce Springsteen to the largest possible venues in the U.S. and around the world. Though tours were once orchestrated to promote the release of a new album, hoping for double-platinum-level sales, it is far more likely that today the touring artist(s) will release an album—often, a compilation of hits or previously unreleased tracks—to coincide with the tour.

Why? Because for many years, tours have been where the real money is made for an artist. Ticket sales, T-shirts, CD sales, all of it can go into the artist’s coffers (after paying the associated costs to promoters and all the staff necessary to stage such an event)—unless the artist has a deal with their label, in which case the revenue has another split.

It was the ongoing success of tours that brought about the 360 deal mentioned earlier in our discussion. Labels wanted to make sure they had a slice of the pie, not only now, but forever after. Consider the revenue generated by worldwide tours, shown in Exhibit 9-5.

8 Pollstar, “2012 Pollstar Year End Top 50 Worldwide Tours,” December 31, 2012.

What’s interesting, when looking at the various acts in the top ten, is the wide variety of artists. Though some might think of popular music as the sole providence of a young crowd, it is evident that performers can extend their lives and their earning power for years, as loyal fans purchase tickets on, in some cases, a nearly annual basis. Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones once said, “I’d rather be dead than singing ‘Satisfaction’ when I’m forty-five.” Now, at the age of 70, he is a prime example of the enduring popularity of some rock icons, not to mention how one’s opinions may change during the aging process.

A megatour is a high-water mark of success for a star or group and indicates a high level of trackable interest: the ability to fill the largest venues throughout America and the world. A promoter—such as LiveNation—orchestrating such a tour must make certain assurances regarding the artist’s responsibilities, while the venue must also be able to assure the promoter that the seats will be filled. A typical tour contract is loaded with “riders,” which ensure both sides other comfort levels. For instance, details may include the exact number and size of lights, sound capabilities, even the specific food or other entertainment that will be available to the artists.

Megatours are the perfect example of the medium becoming the message—the music itself is the main draw, but the message of the star’s bankability that comes from such an event only serves to more firmly place that artist in the firmament of top performers.

Marketing the Music

With a global audience always searching for a new beat, music offers marketers a tremendous ability to reach niche markets. Marketing the product to these eager ears has taken many forms, from pushing the personality to creating new mediums of delivery. But those new mediums—from LPs to 8-tracks to cassettes to CDs—may have masked an inherent weakness in the music industry, at least in the 1990s. With the introduction of the CD, many consumers raced to replace their damaged LPs with a medium touted as nearly indestructible, producing a healthy spike in sales. Then, with the introduction of digitization, another bump occurred, as fans filled their hard drives with downloads. But with the move to downloads and streaming, revenue creeps downward, now based on pennies rather than dollars.

So what’s a product manager, assigned the task of walking a new artist from deal to domination, to do? Fall back on tradition while exploring new opportunities.

Marketing Personalities

Possibly more so than in any other entertainment sector, music depends heavily on the marketing of personality. The hype attendant to any on-stage appearance of a performer is part of the experience machine: getting the audience in a lather before they even enter the auditorium, creating a concert rush that energizes both the performer and the fan. Careers today are built on this phenomenon. But will the superstars of today go evergreen? Will they continue to sell out concerts with an advance? Cross over to movies, TV, books, and other entertainment media? Or will they flame out and disappear into the abyss, abandoned by fans and promoters?

How do they get to the top in the first place?

For the most part, they get there via the marketing machine that only the major labels can mount, selectively employed when everyone on the team believes this is “IT”—a superstar in the making, under contract. All the tactics required to achieve hit status will be employed with support from the top of the company. Multimillion dollar budgets, staffs of professionals in publicity, A&R, advertising, touring, and venue relationships build an enormous opening for a tour touting a new album. Those appearances are backed with countless talk show interviews, leading magazine cover stories, organized fan clubs, and TV appearances. Websites are built, social networking is set in motion—a Facebook page, Twitter, Pinterest. In some cases, a music video will still be produced, released to YouTube or available on Vevo.com, a music video subscription service. The executive in charge of gaining distribution will complete the deals necessary for both digital and hard-media release. Radio airplay will be negotiated. Finally, when the star’s performance/marketing blitz is launched, a groundswell of hype, buzz, and CD purchasing hysteria leads to the reward: The release goes double platinum and pays for all the thousands of non-hits released by the label that year.

Cross-Promotion

Other methods widely used in the marketing of music are cross-selling, tie-in programs, and music brand sponsorship. For example, offering CDs of top performers at a bare bones price of $10.00 with the purchase of coffee at Starbucks is an effective promotion—and everyone wins. The labels get sales on a catalog of already released music; the talent receives a more modest royalty on the large volume sold; the coffee house builds traffic; and the stars receive advertising and display marketing. The ROI is acceptable and leads to sponsorship deals with stars, their managers, and labels.

The Country Music Association (CMA), in connection with Gaylord Entertainment and the Nashville Cable Network (now owned by CBS), holds an annual Country Music Marketing program where deals are brokered. The group helped Trisha Yearwood gain a multimillion-dollar deal with Discover Card and Brooks & Dunn with Lee’s Wrangler Jeans. Garth Brooks and other country music stars “tie up” and receive concert and music video support in return for the endorsement of beverages, cereals, apparel, and automobiles. Music talent and sponsorship agencies put together these highly profitable and successful arrangements; marketing strategies and tactics are borrowed from one high-powered deal to the next. Like all such deals, success breeds higher financial commitments and bigger programs.

Television

Along with the awards shows—The Grammies, BET Awards, American Music Awards, Academy of Country Music Awards, Billboard Awards, and more—there are many possibilities for television exposure for new artists as well as the creative superstar.

One intriguing opportunity took flight in the early part of the century, with the rise of The Artist’s Den. Founded by a young entrepreneur who saw an opportunity in live performance, Live from the Artist’s Den is a three-time Emmy-award-winning PBS program that marries recording artists with interesting and important venues. Be it Ani DiFranco at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, Crowded House at the Masonic Hall Grand Lodge of New York, or Dierks Bentley at the Ravenswood Billboard Factory in Chicago, the Artist’s Den presents musicians in venues that may be every bit as intriguing as their music, with selectively invited fans who relish the idea of hearing their favorite artist—and possibly being in a video, available for download at the Artist’s Den website.

Live from the Artist’s Den is presented evenings on over 50 local PBS stations each year and has been marketed, licensed, and syndicated by Turner Broadcast in cities around the world.

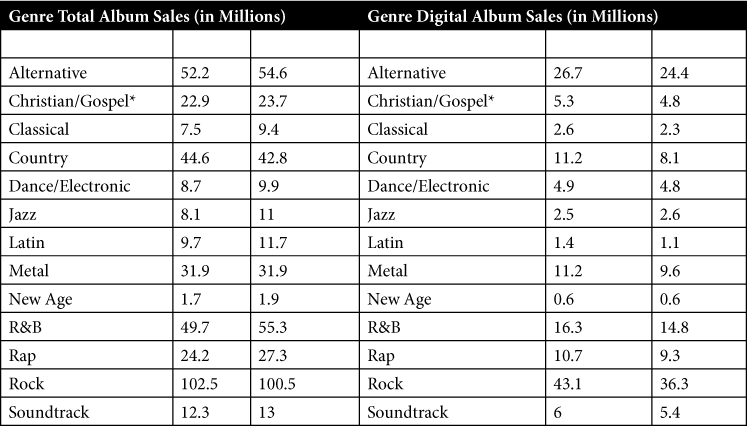

Market Segments

Music truly is the universal language, but it still maintains specific fan bases, regardless of crossover appeal. To demonstrate the changes that digital downloads are bringing to the business, we present a look at the most popular music segments of today. In Exhibit 9-6, note the differences between total album sales on the right and digital album sales on the left. You’ll see that while total album sales might have slipped between 2011 and 2012, digital album sales rose.

9 The Nielsen Company & Billboard’s 2012 Music Industry Report.

In the late twentieth century, as marketers discovered the power of niche products throughout the entertainment universe, the various sectors of the music world saw heightening popularity for a variety of different styles and tastes. When music labels realized the vein of gold running through these segments, they began to mine them for all they were worth—a considerable sum, as it turns out. Niches such as Latin, Hip-Hop, Rap, Techno, and House Music joined old standards such as R&B and Jazz in maintaining not only loyal bases, but in many cases, cross-over appeal.

As the various niches took off, other more traditional segments followed the trend toward new marketing techniques. Classical music got sexier with a focus on such handsome young stars as Joshua Bell (violin) and Josh Groban, a talented singer-songwriter who crosses over from classical to pop.

Opera Hits a High Note

Speaking of crossing over from classical to pop, we have to make mention of Peter Gelb, who brought new revenue to Sony as the head of its American Classical division. At Sony, Gelb mixed cellist Yo-Yo Ma with Americana (country) music and classical singer Charlotte Church with pop. The soundtrack to the movie “Titanic,” the highest-selling film soundtrack in history, was also produced under Gelb’s watch.

In 2006, Gelb took over as the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera, as traditional a venue as one could imagine. In his six years there, Gelb has caused controversy with new productions of long-time favorites—testing the theory that even bad press is good—but raised awareness of the Met significantly by creating Live from the Met, with live performances broadcast in high-definition to movie theaters and, more recently, PBS. The broadcast has been a stunning success, and most important, has given people around the world access to an art form previously entrapped in staid buildings and upper-crust conformity.

Jesus Saves and Also Sells

To the surprise of many in this age of high-profile, highly-sexualized recording artists, religion is the driver behind one of the most popular music genres: Christian music. Live and prerecorded, it is unabashedly dedicated to Christianity and the celebration of Jesus. Christian/gospel digital music sales were up 11.1% in 2012 over the previous year.10

10 Nielsen.

On major TV stations and local channels—especially on Sunday mornings and during Christian holidays—fresh-faced, wholesome, conservatively dressed, and respectful young adults sing rock & roll, middle-of-the-road, pop, and other contemporary rhythms and lyrics that praise Jesus and thank God for all that is good. Lead singers are attractive stars in their own right, while the back-up singers are more a reflection of a church choir than a typical star’s musical entourage.

This category of music is sold as major CD issues through chains of Christian book and religious gift stores throughout the country, driving huge increases in sales revenue. Billboard tracks the “Top Contemporary Christian” albums, including re-entry items such as Elvis Presley’s He Touched Me: The Gospel Music of Elvis Presley. There are few returns to the labels—usually smaller, specialized companies like Word and Spring House (though big labels such as Atlantic do weigh in now and then in the category with hits as well)—since the music is evergreen and has no fad or timing issues. It is unique in the music industry to have a nonperishable product. In addition, the singers are frequently paid minimal salaries and do much of their own marketing and promotion in the service of their beliefs.

Though the strongest sales are in the Bible belt, Southern Baptist strongholds, national Christian shows like Crystal Palace build sales of the music across the country.

Repackaging and Compilations

What late-night TV viewer isn’t familiar with the constantly scrolling, heavily over-voiced commercials touting music compilations? Though this segment has gone through the same shifts as the rest of the music business—including to digital downloads—it’s still a viable business, proving that perhaps it is true: The music never dies.

Entrepreneurs such as Richard Foos and Harold Bronson, who founded Rhino Records but moved on to Shout! Factory, purchase the rights to or license for reuse a variety of music, then repackage it in themes: Hits of the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s; Romantic Love Songs; Party Music; Beach Songs. There is something for everyone, regardless of age, race, or gender. Rhino, now owned by Warner Music Group, has taken the concept one step further by offering videos and books as well as films that are creatively packaged collections of materials from the past.

Legacy Recordings, a division of Sony Entertainment, discovered the formula of reissue and repackaging, utilizing catalogs from Columbia Records and Epic Records and the archives of Sony Music’s RCA, J Records, Windham Hill, RCA Victor, Arista, Buddah Records, Philadelphia International Records, and Sony BMG Nashville. Legacy has access to a vast amount of underutilized properties and has reissued division multi-CD sets featuring Frank Sinatra, Miles Davis, Louis Armstrong, Dave Brubeck, Billie Holiday, the great ladies of early jazz, and many more. Though the marketing behind these releases is minimal, the basic tactics are always vibrant, and the loyalty of customers to the basic brand pays off handsomely.

Soundtracks

The soundtrack genre owes its success and shares its parentage with the movie industry, though it also requires cooperation from the music business to flourish. Usually the process begins with the postproduction of a film and falls into the following categories:

![]() Nonmusical film, utilizing music to heighten the tension or underscore the action, explosions, and random special effects; genres include action-adventure, horror, science fiction, and romance, using music from the public domain or composed by leading film music professionals, such as multiple Oscar winner John Williams. Some of the hundreds of examples include classics such as 2001: Space Odyssey and Sleepless in Seattle, which continue to sell, long past the release of the movie. An ongoing example is the carryover theme from the long-running TV series Mission Impossible, remade for the Tom Cruise Mission Impossible movies.

Nonmusical film, utilizing music to heighten the tension or underscore the action, explosions, and random special effects; genres include action-adventure, horror, science fiction, and romance, using music from the public domain or composed by leading film music professionals, such as multiple Oscar winner John Williams. Some of the hundreds of examples include classics such as 2001: Space Odyssey and Sleepless in Seattle, which continue to sell, long past the release of the movie. An ongoing example is the carryover theme from the long-running TV series Mission Impossible, remade for the Tom Cruise Mission Impossible movies.

![]() Musical film, featuring singing and dancing with new or already written songs to fit the characterization of the acting. This category also consists of films made from Broadway shows. A recent example of this is the soundtrack to the 2012 release Les Misérables. It also includes animated movies like The Lion King, Beauty and the Beast, and Tarzan.

Musical film, featuring singing and dancing with new or already written songs to fit the characterization of the acting. This category also consists of films made from Broadway shows. A recent example of this is the soundtrack to the 2012 release Les Misérables. It also includes animated movies like The Lion King, Beauty and the Beast, and Tarzan.

![]() Movies featuring a leading singer, such as Whitney Houston in The Bodyguard. These movies have songs written or reorchestrated specifically for the film, with additional tracks by other artists. The Bodyguard soundtrack is one of the best-selling albums of all time, having sold over 45 million copies since the movie’s release in 1992.

Movies featuring a leading singer, such as Whitney Houston in The Bodyguard. These movies have songs written or reorchestrated specifically for the film, with additional tracks by other artists. The Bodyguard soundtrack is one of the best-selling albums of all time, having sold over 45 million copies since the movie’s release in 1992.

![]() Blockbuster films that feature unique soundtracks. For example, the Titanic soundtrack, which consisted primarily of orchestral music and featured one song by Celine Dion, became a surprise platinum CD success with worldwide sales of over 30 million copies. During the movie’s first incarnation, the widespread distribution of the CD, the radio play of the theme song, and the huge displays in retail music stores helped to promote and market an extended run of the film. When the film was rereleased in 3D, in 2012, the album was repackaged and enjoyed another run on the charts.

Blockbuster films that feature unique soundtracks. For example, the Titanic soundtrack, which consisted primarily of orchestral music and featured one song by Celine Dion, became a surprise platinum CD success with worldwide sales of over 30 million copies. During the movie’s first incarnation, the widespread distribution of the CD, the radio play of the theme song, and the huge displays in retail music stores helped to promote and market an extended run of the film. When the film was rereleased in 3D, in 2012, the album was repackaged and enjoyed another run on the charts.

![]() Soundtracks for games. The soundtrack for Halo 4 actually debuted at number 50 on the Billboard Chart when the game and the soundtrack were released in 2012.

Soundtracks for games. The soundtrack for Halo 4 actually debuted at number 50 on the Billboard Chart when the game and the soundtrack were released in 2012.

Soundtracks have become a large revenue stream and an excellent promotion and marketing opportunity, including the use of film clips from movie trailers on YouTube. This enlarges the simultaneous marketing of the film, music CD, and digital download.

To take advantage of this opportunity, most film studios work closely with their music divisions; for example, Warner Bros. Studios with WEA, Sony Entertainment with Columbia Music, and Universal Studios with Universal/Polygram Music.

On occasion, music producers or A&R professionals are hired by film producers to locate or develop saleable and marketable music produced years earlier that evokes a certain nostalgia for a period or historical movie.

Ringtones

Back in the Dark Ages—three years ago, in techno-time—pundits were actually predicting that mobile music was on the way out. Part of this doom and gloom was piracy, and part of it was due to the drop in ringtone sales, as consumers figured out ways to “sideways download” their own ringtones, using the music tracks they were downloading. Ringtone sales, you say? Could there really be that much money in those? In 2008, ringtones accounted for over $700 million in mobile music sales. They did in fact, slip, to $167 million in 2012, still nothing to sneeze at.11

11 “Whatever Happened to the Ringtone?”, CNN iReport, May 9, 2013, www.cnn.com/2013/05/09/tech/mobile/ringtones-phones-decline/index.html.

Musical Theater

Music is not limited to records, radio, downloads, or ringtones. For those who seek a live performance with a story to match, there’s musical theater, and most specifically, Broadway musical theater.

Broadway Baby Gonna Make a Billion

Who would guess that this headline could ever have been possible? For decades, Broadway musical theater has been considered the poor stepchild of the entertainment industry, a musty old convention that only attracted die-hard aficionados or tourists in New York. After all, who would want to spend a small fortune to see a staged musical—sitting in cramped seats, with poor air conditioning and ridiculous lines to the loo—when you could sit in a giant arena and have your ears blown out by the likes of Bruce Springsteen or Lady Gaga?

But make no mistake: Broadway musicals sell in the billions (see Exhibit 9-7).

Exhibit 9-7 The Highest Grossing Broadway Musicals, as of February 2013

Source: www.broadwayworld.com

This is a sector of the entertainment business that evolved from the early years of burlesque, slapstick comedy, and small Yiddish theater on the lower east side of Manhattan, fueled by a rather small community of die-hard thespians, chorus kids, and pit musicians who could not imagine life without eight performances a week. Broadway theater is six nights and two matinees a week, repeating the same lines, playing the same notes, over and over—and yet still delivering a fresh experience to every wide-eyed guest in the seats.

The beauty of live theater is the fact that every single performance is different from the last—perhaps not noticeably, but it is, after all, live—no lip-synching or recording. Certain shows are revived over and over: Gypsy has been staged on Broadway five times, including twice in the decade of 2001 to 2010. Each new cast brings a new interpretation. Fans will argue over the greatest Rose: Ethyl Merman, Angela Lansbury, Tyne Daly, Bernadette Peters, Patti LuPone.

It is truly a love affair with an art form, now a huge business.

All the World’s a Stage

The live theater thought of as “Broadway” is a bit of a misnomer, given live theater today is represented by three major centers: Times Square in New York City, the theater district in Toronto, Canada, and the ever-famous, age-old West End in London, England. But even this is only a part of the total U.S. and global live theater picture. Successful—and even not so-successful—Broadway regularly hits the road in national tours, criss-crossing the U.S. in what the actors and musicians refer to as bus-and-truck productions. Add to that the hundreds, if not thousands, of performances put on in cities across the country under contract or license agreements with the folks who own the IP.

Just as important are the regional theaters, where new productions are mounted, sometimes moving to Broadway after successful runs. This could include the productions that are meant as Broadway tryouts at the La Jolla Playhouse in California or the original plays staged by the Steppenwolf Theater in Chicago, a mother lode of recent Broadway transplants.

Now add the staging of these shows in global cities. Imagine hearing Miss Saigon or Phantom of the Opera in Mandarin, German, Italian, French, or Hebrew, performed by a country’s very own best-of-the-best theatrical talent. All of these shows are also under contract with local producer/presenters under tight supervision by the content owners.

Broadway Basics

What qualifies as “Broadway” shows are staged in forty theaters in New York’s Times Square theater district, stretching from 42nd Street to 53rd. To the north, straight up Broadway, the newly renovated Vivian Beaumont at Lincoln Center and the extraordinarily beautiful Alice Tully Hall feature wonderful entertainment. Broadway theater also includes three nonprofit theater companies: Roundabout Theater, Manhattan Theater Club, and Lincoln Center Broadway Theater.

In today’s live theatrical business there is a close relationship between the venue owners and the producers, often being one and the same. Important names in theater ownership include the Nederlanders, the Shuberts, the JuJamcyn organization, the Dodgers, and that “new” upstart, the Disney Theatrical Group. The rock stars of live musical theater continue to be the hyphenate producer-writers-lyricists-composers like Andrew Lloyd Webber, Cameron Mackintosh, Tim Rice, Elton John, and others who have the longevity and passion for this form of entertainment.

Broadway is not for the faint of heart. Though not statistically reliable, producers claim that three out of five shows brought to the stage close soon after, never recouping the initial investments. But those other two go on to make millions for their producers and the investors, keeping performers, musicians, stage hands, dressers, and the rest of the crew in salary checks for years, sometimes—but not always—guaranteed by winning a Tony Award, Broadway’s version of the Oscars.

Today’s Broadway does have its challenges and controversies. What years ago could be staged and presented for small budgets (and even smaller salaries) turned into multimillion dollar sets with crashing chandeliers, descending helicopters, and sinking ships. A most recent incarnation, Spiderman: Turn Out the Dark, cost over $75 million to produce—more than some blockbuster movies—and featured as much drama offstage as on but has still gone on to attract an audience, despite high price-point tickets.

Productions now flout well-known Hollywood names such as Tom Hanks, Scarlett Johannson, or Julia Roberts in an attempt to guarantee bigger payback. This doesn’t always happen, of course; not all film actors are meant to be on stage. The cost associated with hiring these stars—often at salaries that are far higher than what is paid to notable Broadway icons such as Patty LuPone or Boyd Gaines—drive up the overall cost of the production.

Producers are constantly trying to economize in other areas, including the union contracts with stagehands or musicians. There has been an ongoing effort by producers to utilize what is known as a “virtual orchestra”—read, taped music—in place of the musicians who toil in the pit. This seems completely incongruous. After all, should Broadway patrons be forced to pay hundreds of dollars for the type of show they might see in some town in the sticks? Broadway is about live performance, by the professionals who bring the experience to life. And trust us, there are very few musicians who are getting wealthy in this area of entertainment.

Every hit Broadway show now includes a stand near the front door, selling T-shirts, coffee cups, posters and soundtracks. Something to note: The sound you hear from a soundtrack often sounds richer and fuller than what you heard coming from the orchestra pit. Broadway theaters are governed by strict regulations calling for a certain number of musicians in particular theaters. The orchestras that fill these pits are smaller than the orchestras used to record the soundtrack. This was not always so; the famous musicals of the Lerner and Loewe or Rodgers and Hammerstein era featured large orchestras and lush sound. When South Pacific was restaged in 2008—the first time on Broadway since 1949—the producers chose to use a full orchestra. The rich sound welling up during the overture took many theatergoers by surprise. It was Broadway music as it was meant to be heard.

From Stage to Screen

There was a time when a hit Broadway musical was sure to make it on to the silver screen. Notable examples include South Pacific, The King and I, My Fair Lady, Oklahoma, Camelot, and West Side Story. These movies were often presented in theaters in a format that mirrored the stage production: a long overture and an intermission. But the practice slowed down in the later part of the twentieth century, as audience tastes (and Hollywood’s appetite for risk) changed. However, musicals as movies are now making a comeback, including Chicago, Mamma Mia, and most recently, Les Misérables. And, just as with movies, soundtrack sales add to the bottom line.

From Screen to Stage

What’s good for the goose is sometimes good for the gander. Certain movies have been made into musicals with great success: Sunset Boulevard, The Producers, The Apartment (on Broadway as Promises, Promises), Monty Python and the Holy Grail (on Broadway as Monty Python: Spamalot), Mary Poppins, Hairspray, and the current all-time winner in the highest Broadway gross category, The Lion King. But movie success does not always translate to the stage. Disney fans might think that The Little Mermaid would be a natural for the same stage success as The Lion King and Beauty and the Beast, but no. Adam Sandler-style comedy, The Wedding Singer, also had a very short life.

On with the Show

Broadway, like every other entertainment platform, depends on the massive marketing machine to bring it to monetized life. For musical theater, this includes newspaper ads, small boxes in the theatrical ABC listings, billboards, radio promotions, the occasional TV commercial, and appearances in the annual Macy’s Thanksgiving parade.

Ticketing strategies include occasional two-for-the-price-of-one or discounted tickets for same day performances at the TKTS booths found in Times Square, South Street Seaport, and downtown Brooklyn. TKTS is operated by the Theater Development Fund and offers up to 50% discounts on tickets for those who are willing to wait in line just prior to curtain. Not all shows are represented, but the offering is well worth the wait. Broadway.com also offers online ticket sales. In addition, Broadway shows have their own websites, performers have twitter feeds, and Facebook is employed.

For national exposure, there’s the yearly Tony Awards, which offers a vignette of each of the nominated shows, along with the national tours. More than one audience member has sought out “the real thing” after seeing a performance in their home town—and as well they should.

This is not to discount the efforts of those touring companies. Those hardworking professionals bring Broadway to life across the country and often wind up on the big stage themselves. But there’s nothing like the experience of sitting in a Broadway theater. Each of these venues has a story of its own: the famous shows that played for years; the understudies that went on to stardom; the ghost lamp that lights every deserted stage, every dark night. Broadway is a living thing and takes a living audience to bring it to life. Do yourself a favor: Go.

Billboard: The Bible of the Business

It would be impossible to close this discussion of the music platform without mentioning Billboard, the best-known publication in the business.

Founded in 1894, Billboard originally served as a weekly for the billposting and advertising business but evolved into the source for tracking trends and talent. The publication is read by everyone from fans to top executives and stretches into all areas of the business: legal, distribution, retailers, radio, publishing and, of course, the digital domain.

After many years of logging various trends in the business, Billboard launched its Hot 100 chart in 1958, charting all segments of the music business. It is still the standard by which all music popularity is judged in the United States, regardless of genre.

Although Billboard still exists in print, the publication made the transition to the Internet in 1995 and now attracts ten million unique visitors each month in more than 100 countries.12 The site features charts that are both searchable and playable, along with news, interviews, and video.

12 Billboard.com.

Summary

As a universal language, music reaches all ages, cultures, and countries and is found in every sector of the entertainment industry. Whether it appears as a movie soundtrack, a live event, in a downloaded video, over the airwaves, or on the Internet, music reaches listeners in a language all its own. Music serves as both a marketing tool and a marketed medium, driving a multibillion-dollar industry.

For Further Reading

Dannen, Frederic, Hit Men: Power Brokers & Fast Money Inside the Music Business, Vintage, 1991.

Krasilovsky, M. William, Sidney Shemel, John Gross, and Jonathan Feinstein, This Business of Music, 10th Edition (This Business of Music: Definitive Guide to the Music Industry), Billboard Books, 2007.

Lathrop, Tad, and Jim Pettigrew, This Business of Music Marketing and Promotion, Billboard Books, 1999.

Lendt, Chris K., Kiss and Sell: The Making of a Supergroup, Watson-Guptill Pub., 1997.

Passman, Donald S., All You Need to Know About the Music Business: Seventh Edition. Free Press, 2009.

Thall, Peter M., What They’ll Never Tell You About the Music Business: The Myths, the Secrets, the Lies (& a Few Truths), Billboard Books, 2010.

Wixen, Randall, The Plain and Simple Guide to Music Publishing, 2nd Edition, Hal Leonard, 2009.