Developer Name: Dave Witonsky and Randall Barnhart

Development Company: Intermap

Tags: Compression; Efficient Code; Release Strategy

URL: http://accuterra.com

"We have roughly 170 products on the shelf today," says Dave Witonsky, head of smartphone development for Intermap. He's not talking about apps. He's talking about in-app purchase items: hyperdetailed maps that users can buy and download as they travel. Welcome to the dizzying world of AccuTerra: the iPhone's titanic terabyte app (see Figure 5-1).

Figure 5.1. "I want this app to help people plan their trips, view their trips, and share them. I want it to enhance that experience of being in the outdoors," says Witonsky.

Unlike the rest of the apps profiled in this book, AccuTerra, which won the ADA for beta use of iPhone OS 3.0, was awarded an Apple Design Award not for what it did, but for what it has the potential to do. And although Intermap's app is now in the App Store, it's still AccuTerra's incredibly ambitious roadmap that sets it apart from the crowd. And although not every developer has access to the mapping data from a multimillion-dollar navigation company, AccuTerra shows how developers of all stripes can build massive data-intensive apps—and do it profitably.

Intermap is not just an iPhone development shop; it's a map-data provider. "We have flown all over the U.S. and western Europe to collect highly detailed mapping and elevation information," Witonsky explains, "and we have very accurate models of the earth that contract out to governments, flight insurance companies, and OEM personal navigation companies." Intermap, in other words, is not your average Mac shop that has decided to tool around with a new platform. In building a deeply complex app, they have a lot at stake.

NEXTNat, the company's name for its map data, gets around because of its level of detail: automotive, trucking, and flight companies use Intermap's data because it includes elevation, hydrological data, and other matrices of info. Witonsky says that Intermap saw that personal navigation devices were giving way to smartphones, and they figured they could ditch the middlemen—companies that make personal navigation devices—and bring their data straight to consumers. "So we built early prototypes for the iPhone, and of course, this tsunami of popularity came," Witonsky says.

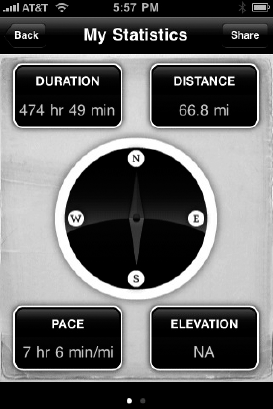

As the iPhone proliferated, the scope of Intermap's app expanded. "We focused first on national park trails and research, and then pulled these trails and description and attributes from guidebooks and other public sources," Witonsky says. Then his team consolidated and verified their data, and started working on making the rest of the nation's detailed maps available, too. Witonsky wants AccuTerra to someday be a one-stop outdoor guide for the entire contiguous Untied States. "Eventually I'll be able use the app to put in, say, Mars, Colorado, and choose [trails of] moderate difficulty," he says. "Then let's say I'd rather not see what's called tight-usage, or trails with horses and mountain bikers on it; I'd rather just hikers-only. The way we're building this thing, we can provide them two or three choices based on our algorithm. The next thing the person will want to know is the 3D profile, which will leverage our NEXTNat high-resolution elevation model. They can see how steep a trail is." Figure 5-2 shows AccuTerra's information dashboard.

As opposed to some of the other navigation apps that leverage Google Maps or Open Street maps, AccuTerra uses all of Intermap's own map data. "Other apps could integrate to the MapKit framework and get things out faster," Witonsky says. "Our value-add, a big one, is that we're onboard. We used our own mapping framework; we built it from scratch."

"We did take a lot of cues from MapKit," says Randall Barnhart, the lead developer of Intermap's five-man team. "And we do also use MapKit to interface with Google, so that we can provide people who are doing recordings in an urban area with the option of using Google maps instead [of Intermap's] if they want." But building their custom map-kit was the brunt of the work behind the app. "It was an absolutely massive undertaking," Witonsky says.

Intermap's other killer feature is detail. But being able to fetch a detailed map of every square mile of the U.S. requires a lot of images—far too many for a single app, or even for a dozen apps. The team decided to build an in-app map store so that users could buy detailed maps as they needed them over their 3G connection, delete old ones if they needed space, and re-download the ones they've already bought. Along the way, they had to figure out how to mate their purchasing back-end with Apple's, and how to deliver gigabytes of map data over the air.

Apple's terms and conditions require that all in-app purchases go through the App Store. There are ways around that—several e-book apps have eschewed the rule—but Witonsky thought it better to stay on Apple's good side if his company was going to pour so much money and effort into their app. But following the rules meant that map downloads and payments would have to take a convoluted route.

"We made the decision that we were going to rasterize all of these trails and all the different levels of detail—hydrology layers and so on—all in the raster image," Witonsky says. "When these maps raster, when you start talking about an entire state, the country, earth, this stuff is heavy. Even if you're using PVRTC, if you're at high-resolution these things are 512kb per tile. It adds up real quickly."

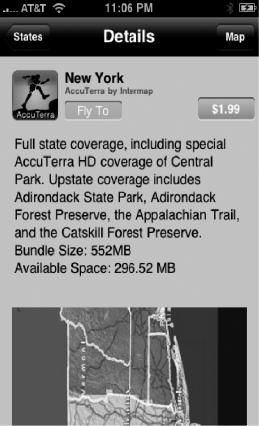

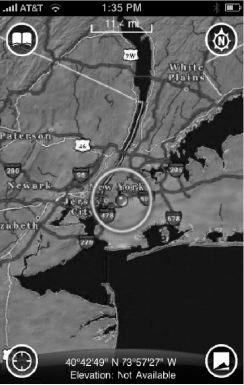

Had they packaged the entire app with every available U.S. map, Witonsky says, it would have been well over a terabyte. "We considered going out the door with different states bundled with our application," he says. "Each bundle, of course, would be one app on the App Store that we could charge someone $10.00 for. By the time we split up all the states, and the larger states into sections, lo and behold, we were up to 70 bundles. It was just too confusing." IPhone OS 3.0 brought in-app purchasing, saving Intermap from having to inundate the App Store. Instead, it built a map store inside AccuTerra. "We figured we could release this one app, and sell the other maps piecemeal—though the basic app is a bit heavy at 110MB because it contains continental data. But on top of that, we figured we could side load these other contents: your wide-area maps, big states, national parks and recreational areas." (Figure 5-3, AccuTerra's pre-installed "continental" view of New York.)

Figure 5.3. AccuTerra provides users with an overall view, but for more detail, additional maps must be purchased.

AccuTerra's map store is entirely separate from the App Store, but it must communicate with Apple's servers to coordinate purchases. To make the hand-off fluid, Intermap's engineers designed their in-app catalog to be consonant with the Apple experience. "The map store is highly modeled on the actual App Store itself," says Barnhart, who began his career at defense contractor Raytheon doing Java work application development. "How we categorize products, how we have these table views; how you tap a row, get more information about it, or go down a level; we're using a lot of the built in UI-kit user interface to do a lot of the same things that you'd see in Apple native apps," he says.

In-app purchases in AccuTerra deliver tiles of a region in various resolutions: the medium-quality Continental maps are what Intermap calls 32-degree/8-degree/2-degree-quality images, and the higher definition maps, used in parks and recreational areas, are designated 30-minute/7.5 minute/2.5 minute images. "That is a full stack stored locally, so when you pinch and zoom, you're not connected over 3G or WiFi," says Witonsky. "This is a huge thing for us, because our maps are resident on the device, unlike Google Maps which come in over the network."

The levels of detail depend on the area a user buys. If you in-app purchase a state, and you get the 30 minute and 7.5 minute-level of detail; when they get the national parks and other high-use recreational areas, you get 2.5 minute-level maps, which are higher resolution. Future versions of AccuTerra will go even more in-depth. "We're creating version 2.0 of AccuTerra, which will have more trails, better roads, everything—and for that we're creating all new 30s, all new 7.5s, and 2.5s for the whole U.S.," Witonsky says. Translation: the app's enormous 400–600MB maps are getting even heavier.

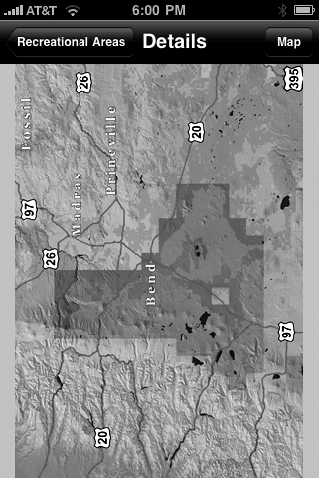

Witonsky says he'll solve the problem by making the app-buying location-aware: drive to a trail-head and the app gives you the option of downloading a map of the five square miles around you. "This is where on-demand buying becomes appealing," Witonsky says. "If we split the maps into five-square-mile tiles, each one ends up less than 10MB and I can download it via 3G or EDGE." Figure 5-4 shows a list of maps available for sale.

Apple's restrictions made AccuTerra's massive in-app catalog a peculiar task. Because the maps are what Apple deems a "non-consumable" product, Intermap has to register each purchase on its server, so that the system knows which maps a user has bought, and won't make him pay if he wants to download that same map again. But because Intermap can't access a user's iTunes account name for privacy reasons, they have to ask each customer to sign up with new credentials on a separate Intermap system. "There's a real twist when it comes to managing your content, because as the developer I have to give you the ability to uninstall a given state map to free up space," Witonsky says. "But I have to list that map in my store as 'uninstalled' status so that you can get that map again. But because StoreKit doesn't track your purchases, at first the App Store doesn't know you already purchased this state. So we have to pop up a little alert, and say, 'Hey, if you bought this under the same iTunes account, you're not actually going to be charged, even though the in-app store says 'buy,'" he explains. "Once you hit 'buy' again, we get that transaction, we know you already bought it, and our server sends it back to your phone for free. That's how you have to manage selling a large set of data." Figure 5-5 shows a catalog listing for the New York State map; Figure 5-6 shows a map's coverage area.

Barnhart says the trickiest part was keeping the sets of information straight. "Developing the in-app store capability raised a lot of issues, since we have our own server that keeps track of users and what map they've downloaded," he says. "But at the same time, there's Apple's framework StoreKit, which also enabled the e-commerce transaction to take place using the person's iTunes account. So we have a bit of duplicate information there, as far as the names of things purchased. So an interesting thing from our side is that our server has to go out and we look for our list of products, then have to come back and make a request out to Apple to say, 'Okay, which of these products on your side are also signed with the same information and are ready for sale?' Then we use that list to display to the user what is ready for purchase," he says. He contrasts the experience to selling apps for Google's Android platform. "We didn't go out and do our own e-commerce thing, because we were bound by Apple's terms and conditions. But if you go to a different platform like Android, all the people that are doing e-commerce through their app are just essentially connected to their own server."

The in-app purchase system also creates confusion when it comes to documenting purchases—something that is crucial when a user can spend upwards of $200 inside a single app. "There are issues with keeping track of receipts and transactions that Apple has on their side, versus transactions and receipts that we're tracking," Barnhart says. "For example, what happens if someone interrupts the download halfway through? What's the best way for us to resume? Is it to go through Apple and see if they have that same transaction, or should we go through our server side? Or do we go through both?" Eventually, Intermaps' engineers figured out that the best way to handle this scenario was to have the app check for outstanding transactions with Apple. "If it's something that the user pauses or cancels themselves, our app considers [itself] done with the transaction," Barnhart explains. "That said, the user can come back anytime and query our servers and see that, yes, they have this product installed, and they can go ahead and download it for free again without having to go through any kind of iTunes transaction."

Of course, it's not always that easy, says Witonsky. "There's a stumbling block with the way they've set up their [StoreKit] framework that can create problems for users who are resetting their phones, or are trying to transfer data over to new phones," he explains. "It's not a big scenario, but it's a complication. When purchase information is stored in two places, it's harder to make it clear to the user what's happening, and how they can get their data back."

In Chapter 3, we discussed using PVRTC to compress images economically. For AccuTerra, PVRTC was not only a nice way to cut down on memory-hogging—it was the difference between a usable app and an unusable one. "Because we use PVRTC, we can fit a number of tiles in memory, and therefore the user experience of panning and zooming is much better, because the app doesn't have to go outside the data structure and bring back more tiles," Witonsky explains. But there are always limitations; because the app can't possibly load all the tiles from a given stack, it has to decide which ones take priority. "We developed sophisticated algorithms to manage that which tiles get loaded," he says.

Barnhart says the algorithm essentially tries to predict what area of the map the user will want to see next, and load it in memory. "The algorithm does a lookup based on the screen location reference and finds the appropriate map tile to display at the appropriate scale," he says. Behind the scenes, the app is being judicious about what it loads. "We had to become very knowledgeable about the frameworks, and know how to receive memory warnings from the OS. [The OS] will tell you, 'Hey, you better free up resources you aren't using,' or 'Hey, you better release this.' Handling those warnings challenged us greatly."

The situation became complex when it came time to add ancillary features to the app. "Everyone wants to use the camera inside the app, but through the [camera] framework, Apple takes over memory, then hands you memory back," Witonsky says. "We found that when they handed everything back, we ended up pushing the envelope with memory and we'd have to release view-controllers and everything. We had to go back and work very hard to optimize everything so that other frameworks or background processes wouldn't cause the app to get killed."

Other Apple apps exacerbated the problem. "We kept running into a problem where if someone had loaded up Safari with four or five different web pages, it was caching that information in memory and making our application's available memory space a lot smaller," Barnhart says. "We were running into this issue that when you were recording a trek and you took a picture, like maybe on the fourth or fifth time, our stream would freeze." The engineers realized that their app was being issued memory alerts by the OS when they came close to hitting the limit, but that the app wasn't doing anything with those alerts; it was just logging them and continuing business as usual. "After a lot of debugging, we realized that Apple's framework gives you levels of warning, and if you cross the threshold where there's maybe only 5% available memory for your application, it starts yanking things," Barnhart says. Having camera view on top of map view, a bunch of tiles loaded up, and trip breadcrumbs was too much for the OS to handle. "We came to realize that the view pointer for that view controller was getting yanked out from underneath us from the system, and when it came back from taking the picture, lo and behold, if we were trying to reference a button that was connected to that view, the app would crash."

After asking around at WWDC and scouring Apple message boards, Intermap's coders eventually figured out how to handle the low memory conditions the OS was warning them about. The solution: lazy loading.

In the app's initial design, for example, it created its map buttons upon launch, and only did it once. But once memory became low, the OS would pull the root view out from underneath the app in order to prevent a crash. "We came to realize we have to create these buttons as late as possible," Barnhart says, "because there are these other delegate methods that appear that could get called from Apple's API when these events happen in the UI. We realized that you have to initialize these things and wire them up in those instances, so that in the event the root view gets pulled, you can rewire things." Once they began to delay loading, they could load on as many Safari pages or photos as they wanted without a crash.

The trick, Barnhart says, was knowing what to release from memory when resources were low. "We got some advice from Apple engineers to release IB buttons, these special UI objects. At a certain point, Apple will call this message and tell us, 'Okay, we've pulled the root view, you need to try to release as much memory as you can.' Then they essentially call these delegate methods, saying, 'Okay, I'm initializing it; I'll initialize that once.' But every time I show the root view, I'm going to call this other method. That's where we have to wire things up correctly. It was definitely an interesting lesson learned for us."

The other lesson, says Barnhart, was to get to know the IDE tools before mucking through a problem. "Using Instruments to profile memory is absolutely crucial, he says. "I'd say definitely learn that stuff—it's very valuable in tracking down problems, and just to see how your code is performing in general. I would say that's the one skill that will differentiate people who build better apps from the people who don't."

To easily determine and query current memory within the running app, AccuTerra defines the following functions in our main app delegate class:

(declarations)

// system memory query methods

+ (vm_statistics_data_t) retrieveSystemMemoryStats;

+ (int) calcSystemPageSize;

+ (int) calcSystemAvailableMemoryInMB;

+ (int) calcSystemRemainingMemoryInMB;

+ (int) calcSystemPercentFreeMemory;

+ (BOOL) doWeHaveEnoughFreeMemory:(int)numOfBytesRequested;

(implementations)

+ (vm_statistics_data_t) retrieveSystemMemoryStats

{

mach_msg_type_number_t count = HOST_VM_INFO_COUNT;

vm_statistics_data_t vmstat;

host_statistics(mach_host_self(), HOST_VM_INFO, (host_info_t)&vmstat, &count);

return vmstat;

}

+ (int) calcSystemPageSize{

size_t length;

int mib[6];

int pagesize;

mib[0] = CTL_HW;

mib[1] = HW_PAGESIZE;

length = sizeof(pagesize);

sysctl(mib, 2, &pagesize, &length, NULL, 0);

return pagesize;

}

+ (int) calcSystemAvailableMemoryInMB

{

int pagesize = [Trek_AppDelegate calcSystemPageSize];

vm_statistics_data_t vmstat = [Trek_AppDelegate retrieveSystemMemoryStats];

return ((vmstat.wire_count + vmstat.active_count + vmstat.inactive_count + vmstat.free_count) * pagesize) / 0x100000;

}

+ (int) calcSystemRemainingMemoryInMB;

{

int pagesize = [Trek_AppDelegate calcSystemPageSize];

vm_statistics_data_t vmstat = [Trek_AppDelegate retrieveSystemMemoryStats];

return ((vmstat.free_count * pagesize) / 0x100000);

}

+ (int) calcSystemPercentFreeMemory

{

vm_statistics_data_t vmstat = [Trek_AppDelegate retrieveSystemMemoryStats];

double total = vmstat.wire_count + vmstat.active_count + vmstat.inactive_count + vmstat.free_count;

double free = vmstat.free_count / total;

return (int)(free * 100.0);

}

+ (BOOL) doWeHaveEnoughFreeMemory:(int)numOfBytesRequested

{

int pagesize = [Trek_AppDelegate calcSystemPageSize];

vm_statistics_data_t vmstat = [Trek_AppDelegate retrieveSystemMemoryStats];

if((vmstat.free_count * pagesize) > numOfBytesRequested)

{

return YES;

}

else

{

return NO;

}

}It then uses these to display in log messages or alerts as follows:

/**

* This method handles Check Memory view

*/

- (void) handleCheckMem_View

{

Log( @"handleCheckMem_View" );

int availMem = [Trek_AppDelegate calcSystemAvailableMemoryInMB];

int remainMem = [Trek_AppDelegate calcSystemRemainingMemoryInMB];

int percentFreeMem = [Trek_AppDelegate calcSystemPercentFreeMemory];

NSString* memStr = [[NSString alloc] initWithFormat:@"Total Available: %iMB

Amount Remaining: %iMB

Percent Free of Total: %i%%", availMem, remainMem, percentFreeMem];

NSString* msg;

if(remainMem < 5)

msg = [[NSString alloc] initWithFormat:@"Low memory!

%@", memStr];

else if(remainMem < 15)

msg = [[NSString alloc] initWithFormat:@"Average memory.

%@", memStr];

else

msg = [[NSString alloc] initWithFormat:@"High memory.

%@", memStr];

Log(msg);

// Debug development team detailed low memory message.

UIAlertView *memalert = [[UIAlertView alloc] initWithTitle:@"Current Memory" message:msg delegate:self cancelButtonTitle:nil otherButtonTitles:@"OK", nil];

[memalert show];

[memalert release];

[memStr release];

[msg release];

}The amount of memory available to your application depends upon the device's available runtime memory. The iPhone 3G has 128 MB and the 3GS has 256MG. But because the OS and services like Mail, iPod, and Safari may be running in the background, the amount of memory available to your application on the iPhone 3G usually starts out at between 20 and 60 MB. The OS keeps track of how much memory your app is currently consuming and will try to free memory if it detects your app crossing certain thresholds of memory consumption.[8]

As Apple's documentation says:

At 80% consumption, the OS will issue a memory warning, which your app can respond to by implementing the didReceiveMemoryWarning function in your view controller classes. This gives you an opportunity to try and release any memory that you don't currently need (like things you may be caching).

At 90% consumption, the OS will begin to remove memory underneath you. Specifically, if you have views in a stack, any views not visible will have their view pointers reset. Because of this possibility, developers need to handle this situation in two ways.

Implement viewDidUnload and release any IBOutlets.

Make sure the creation of your view (any buttons or drawing) occurs as late as possible in the order view creation call hierarchy (awakeFromNib, viewDidLoad, viewWillAppear, viewDidAppear).

Here is how the Intermap developers handled their low memory bug, which was causing the screen to freeze after the user took a photo with the camera while inside AccuTerra. "The view pointer was getting reset causing references to buttons within that view to be bad," explains Barnhart.

In their RootViewController.m class, the root view used for lifetime of app running, the code goes like this:

- (void)didReceiveMemoryWarning {

Log(@"RootviewController::didReceiveMemoryWarning ************************************");

if (!didReceiveMemoryWarning)

{

if (curlingUp || photoTaken)

{

// Remove all subviews

}

}

}

/**

* Overridden from UIViewController:

* Called when the controller's view is released from memory

*/

-(void) viewDidUnload

{

// Release all of our IBOutlets

}

//called after taking photo as the modal picker is dismissed

-(void) viewDidLoad

{

[self restoreViewsForLowMemoryWarning];

[super viewDidLoad];

// ... more initialization code here ...

}

//may be called many times

- (void)viewDidAppear:(BOOL)animated

{

Log(@"RootViewController::viewDidAppear");[self restoreViewsForLowMemoryWarning];

[self.navigationController setNavigationBarHidden:YES animated:NO];

// ... more initialization code here ...

}

- (void)viewWillAppear:(BOOL)animated

{

Log(@"RootViewController::viewWillAppear");

[self restoreViewsForLowMemoryWarning];

[super viewWillAppear:animated];

// ... more initialization code here ...

}"This function is important because it is what allows us to reconnect the view pointer that is removed from underneath us with all the elements that critical to showing our main map view," says Barnhart:

-(void) restoreViewsForLowMemoryWarning

{

if (didReceiveMemoryWarning)

{

// Create and add subviews

didReceiveMemoryWarning = NO;

}

}The Intermap team's accomplishments with AccuTerra pale in comparison to their aspirations. Witonsky says that in subsequent iterations of the app, map graphics will switch to vector drawing, so that users can turn on and off layers of detail and like camp grounds, trailheads, and weather. Users will also be able to toggle between Google Maps and AccuTerra maps, or Google's other views, Satellite and Hybrid.

The goal, Witonsky says, is to be able to start recording a hike in AccuTerra, take pictures, check out a Google map, and continue to keep your breadcrumb trail the whole time. But that's only the beginning. "Version 3.2 is going to allow our users to import and export into all these UGC sites like trails.com, or any site that exposes their API," he says. "Let's say you put in a search for Westchester [New York]; you'll see a list of perhaps 10 trails that users uploaded, and you can download them onto our maps as a layer," he says. "We are also putting a search interface on our maps and a resident database, so when you put in a campground or another POI, it'll find that thing, geocode it to a lat-long location, and easily move you to that location on our map or Google's maps." That, Witonsky says, will allow the map to jump to the location of the thing the user searched for, without the need for scrolling and panning. "That then sets me up for the on-demand purchase interface, for buying that 5 square mile map area of the place you searched for," Witonsky explains. "That's the killer feature."

All that means writing adaptable code. "We've kind of gone over high-level features that are coming down the road, and I tell [my team] to keep in mind: any kind of content could be coming down through the library through an import, whether it be geotagged photo or a geotagged website," Witonsky says. "We've got to keep in mind that when we're designing this next UI, that we have to be able to make it extensible and chock it full of placeholders for all these things that are coming down the road."

What's down the road? Augmented reality. "After version 3.2, 3D will be next, Witonsky says, "and it'll all be tied into this trip planner." The app will contain an algorithm that will take all the parameters of an outdoor trip you want to do—location, length, difficulty, and trail-use type—and show you a list of potential routes. "Once you get the results, you'll be able to do a 3D flyover of the area [on the phone]," Witonsky says. "If you like the area, you can purchase the map bundle, and away you go."

Intermap believes their audience will grow as AccuTerra grows, from outdoors-lovers to history buffs and eventually into the education market. "In my opinion, multimedia is what's really going to win this [augmented reality] fight," Witonsky says. "So not only will you be able to buy a map of a Civil War battlefield, but you'll get audio clips, pictures, text, video and descriptions of trail hikes," he explains. "You could be hiking and there'd be icons that pop up in your view representing a relevant audio or video clip for that spot," he says. "That's the true vision of this product."

Much of that vision will depend on Intermap finding partnerships with content providers, but Witonsky says he's confident the app will progress as planned—and at breakneck speed. "I have a roadmap that in six to nine months that I'm going to have a lot of it done," he says. "This thing is moving so fast that it feels like a tsunami."

[8] "This document was helpful to us while we were solving memory issues," says Barnhart: http://developer.apple.com/iphone/library/featuredarticles/ViewControllerPGforiPhoneOS/BasicViewControllers/BasicViewControllers.html#//apple_ref/doc/uid/TP40007457-CH101-SW4