Chapter 11. The Free Programs of macOS

Right out of the box, macOS comes with a healthy assortment of about 50 freebies: programs for sending email, writing documents, doing math, even playing games. Some have been around for years. Others, like Maps and Books, are newer. They’re designed not only to show off some of macOS’s most dramatic technologies, but also to let you get real work done without having to invest in additional software.

Your Free Programs

A broad assortment of programs sits in the Applications folder in the main hard drive window, and another couple dozen less frequently used apps await in the Applications → Utilities folder.

This chapter guides you through every item in your new software library, one program at a time. (Of course, your Applications list may vary. Apple might have blessed your particular Mac model with some bonus programs, or you may have downloaded or installed some on your own.)

Tip

A reminder: You can jump straight to the Applications folder in the Finder by pressing Shift-![]() -A (the shortcut for Go → Applications), or by clicking the Applications folder icon in the Sidebar. You might consider adding the Application folder’s icon to the Dock, too, so you can access it no matter what program you’re in. Shift-

-A (the shortcut for Go → Applications), or by clicking the Applications folder icon in the Sidebar. You might consider adding the Application folder’s icon to the Dock, too, so you can access it no matter what program you’re in. Shift-![]() -U (or Go → Utilities) takes you, of course, to the Utilities folder.

-U (or Go → Utilities) takes you, of course, to the Utilities folder.

App Store

See Chapter 5 for full details on the Mac App Store.

Automator

This software-robot program is described in a free downloadable PDF appendix to this chapter, “Automator & AppleScript.” You can download it from this book’s “Missing CD” page at missingmanuals.com.

Books

Books (formerly called iBooks) is Apple’s ebook reading program. It lets you carry around dozens or hundreds of books, which, in the pre-ebook days, would have drawn some funny looks in public.

The beauty of all this is iCloud syncing. If you’re reading a book on your iPhone in line for the DMV, you’ll find that your iPad opens up to exactly the same page when you’re on the train home. And when you open your MacBook at home, the book will be on the same page as where you left the iPad. Your books, documents, notes, highlighting, and other details are synced among your Apple gadgets, too. (You can turn that syncing feature off in Books → Preferences → General if it spooks you.)

Most people think of Books as a reader for books that Apple sells on its iTunes bookstore—best-sellers and current fiction, for example—and it does that very well. But you can also load it up with your own PDF documents, as well as thousands of free, older, out-of-copyright books.

Tip

In the interest of fairness, it’s worth noting that Amazon’s free Kindle app, and Barnes & Noble’s free B&N eReader app, are much the same thing—but offer much bigger book libraries at lower prices than Apple’s.

Downloading Books

To shop the Books bookstore, open the Books app. Click Book Store in the upper-left corner; the app becomes the literary equivalent of the App Store, complete with the icons across the top. The links here offer everything you’d need in your bibliographic quest: Bestsellers, Read It Before You Watch It (movie tie-ins), and so on. You can also search by name or click Purchased to see what you’ve bought.

Note

Once you’ve bought a book from Apple, you can download it again on other Macs, iPhones, iPod Touches, and iPads. Buy once, read many times. That’s the purpose of the Not in My Library tab, which appears when you click Purchased.

But unless you have some kind of privacy concern, you may as well tell Books to download your books automatically as you buy them on your other Apple gadgets. Open Books → Preferences → Store and turn on “Download new purchases automatically.” That way you’ll never forget what you bought on your iPad as you sit down at your Mac.

Once you find a book that looks good, you can click Get Sample to download a free chapter, read ratings and reviews, or click the price itself to buy the book and download it straight to the Mac.

If you see a book cover bearing the ![]() icon, that’s a book you own—it’s available in your online locker—but you haven’t downloaded it to this Mac yet. Click to download.

icon, that’s a book you own—it’s available in your online locker—but you haven’t downloaded it to this Mac yet. Click to download.

ePub Files

Apple’s bookstore isn’t the only way to get books. You can also load up your ebook reader from your computer, feeding it with ePub files.

Actually, ePub is the normal Books format. It’s a very popular standard for ebook readers, Apple’s and otherwise. The only difference between ePub documents you create and the ones Apple sells is that Apple’s are copy protected.

To add your own ePub documents to your Books library, just drag their icons off the desktop and into the Books window. Or choose File → Add to Library.

And where are you supposed to get all these files? Free (and not free) ebooks in ePub format are everywhere. There are 53,000 free downloadable books at gutenberg.org, for example, and over a million at books.google.com—oldies, but classic oldies, with lots of Mark Twain, Agatha Christie, Herman Melville, H.G. Wells, and so on. (Lots of these are available in the Free pages of Apple’s own Books store, too.)

PDF Files

Books can display and catalog PDF documents, too. PDFs are everywhere—people send them as attachments, and you can turn any document into a PDF file. (For example, on the Mac, in any program, choose File → Print; in the resulting dialog box, click PDF → Save as PDF.) You bring them into Books by dragging them into its window, or with File → Add to Library.

When you double-click one, though, it doesn’t open in Books; it opens into Preview. Which is, after all, a program expressly designed for reading PDF documents.

You’ve been warned.

Your Library

When you open Books, you see your own personal library represented as little book covers (Figure 11-1). Mostly what you’ll do here is click a book to open it. But there are all kinds of other activities waiting for you:

You can reorganize your bookshelf. Use the Sort By pop-up menu to choose Most Recent or Title—or Sort Manually, which means you can drag books around into any order you like.

You can view your library as a compact list. Click List at the top to switch the book-cover view to a much more boring (but more compact) list view. The column headings let you sort the list by author, title, category, and so on. And there’s a search box, too, which lets you search your books’ titles—helpful if you have an enormous library.

To delete a book, click it and then press the Delete key; confirm in the warning box. Of course, deleting a book from the Mac doesn’t delete your safety copy on your other gadgets or online.

Organize your books into folders. In Books, the “folders” are called collections, but it’s the same idea. You might have one for school, one for work, and a third for somebody who shares your Mac, for example.

To see your collections, click Collections; the Collections list opens at the left side. Make a new collection by clicking the + button (or choose Use File → New Collection); type to name it.

Now, to file your books away, select them (you can press

as you click to select multiple books); then choose File → Add to Collection and choose the name of the collection you want them in.

as you click to select multiple books); then choose File → Add to Collection and choose the name of the collection you want them in.

Figure 11-1. Your Books library is more than just book covers. Stamps at the top-right corner indicate which are new, which are free samples, and which are actually online, waiting to be downloaded ( ).

).

In the Sort By pop-up menu (upper right), you can choose Show Title & Author to add that information beneath the book covers.

Reading

But come on—you’re a reader, not a librarian. Here’s how you read an ebook.

Open the book by double-clicking the book cover. Now the book opens, ready for you to read. Looks great, doesn’t it (Figure 11-2)? If you’re returning to a book you’ve been reading, Books remembers your place.

Tip

You can open several books at once, you multitasking maniac.

In general, reading is simple: Just read. Turn pages like this:

Press the space bar. (Add Shift to turn back a page.)

Tap the

key. (Press

key. (Press  to turn back.)

to turn back.)Point to the right margin; click the > button that appears. (Left margin to go back.)

Swipe two fingers across the trackpad—to the right (to go forward) or left (to go back a page).

Tip

The Touch Bar, if you have one (“The Complicated Story of the Function Keys”), displays a handy “map” of the entire book. By clicking it or dragging your finger through it, you can jump directly to a different spot in the book. As you drag, your main screen shows the page number you’re about to open.

What’s super cool is that, after having jumped to that distant spot to check something, the Touch Bar then offers you a ![]() button, which teleports you right back to where you were.

button, which teleports you right back to where you were.

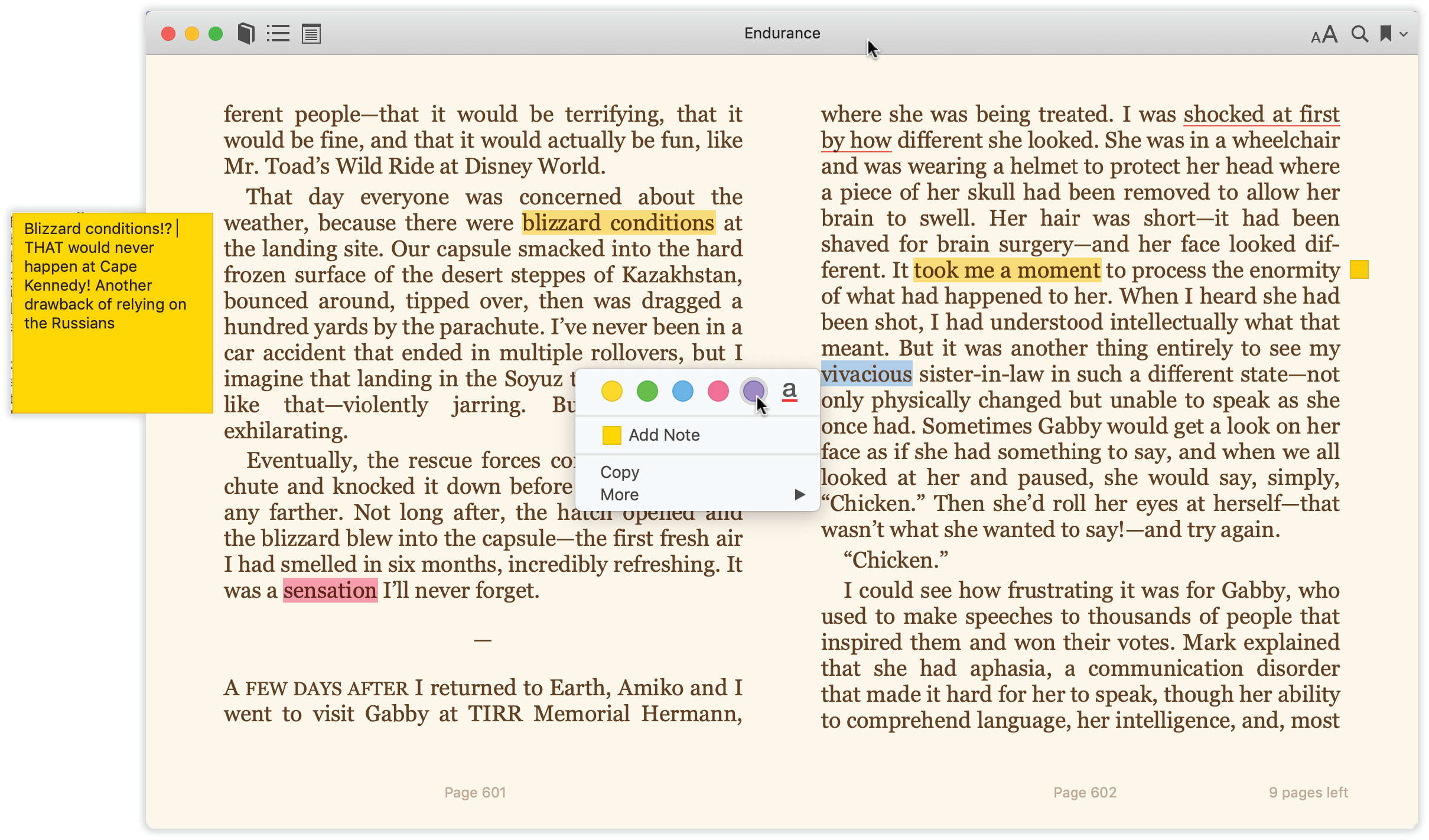

Figure 11-2. Here’s a composite shot showing all kinds of Books features: a Note open (left), the highlighting palette (middle), and the navigation bar (top).

Ordinarily, the reading experience is much quieter.

You should also take a moment to adjust your reading environment. For example:

Enter Full Screen mode for the biggest, least distracting view of your book (see “Full Screen Mode”).

Specify either a one-page or a two-page spread (use the Single Page or Two Pages commands in the View menu). In Full Screen mode, Single Page isn’t available.

Adjust the type size using the

button. That’s a huge feature for people with tired or over-40 eyes. And it’s something paper books definitely can’t do.

button. That’s a huge feature for people with tired or over-40 eyes. And it’s something paper books definitely can’t do.The same pop-out panel offers a Fonts menu, where you can choose from eight typefaces for your book.

Adjust the background color. The

button also offers a choice of four page-background colors: white, sepia (off-white), brown (with white text), or black (for nighttime reading).

button also offers a choice of four page-background colors: white, sepia (off-white), brown (with white text), or black (for nighttime reading).

While you’re reading, Books makes all the onscreen controls fade away so you can read in peace. But if you move your mouse to the top of the window, a row of additional controls appears (Figure 11-2):

takes you back to the bookshelf (Library view).

takes you back to the bookshelf (Library view). opens the Table of Contents panel. The chapter or page names are “live”— you can click one to jump there.

opens the Table of Contents panel. The chapter or page names are “live”— you can click one to jump there. opens the Notes panel, described next.

opens the Notes panel, described next. opens the search box. It lets you search for text within the book you’re reading, which can be extremely useful.

opens the search box. It lets you search for text within the book you’re reading, which can be extremely useful. adds a bookmark to the current page. This isn’t like a physical bookmark, where there’s only one in the whole book; you can use them to flag as many pages, for as many reasons, as you like. (The same button appears on your Touch Bar, if you have one.)

adds a bookmark to the current page. This isn’t like a physical bookmark, where there’s only one in the whole book; you can use them to flag as many pages, for as many reasons, as you like. (The same button appears on your Touch Bar, if you have one.)Once you’ve accumulated a bookmark or two, use the

next to the

next to the  menu to see a list of them—and to jump back to one.

menu to see a list of them—and to jump back to one.

Tip

A Books book can include pictures and even videos. Double-click a picture in a book to zoom in on it.

Notes, Highlighting, and Other Options

Here are some more stunts that you’d have trouble pulling off in a printed book. If you double-click a word, you get a graceful, elegant page from Books’ built-in dictionary. You know—in the unlikely event that you encounter a word you don’t know.

If you drag across some text to highlight it, you get a few surprise options (Figure 11-2):

Highlight. Click one of the colored dots to add tinted, transparent highlighting, or underlining, to the word you clicked. (To remove highlighting, click inside a highlighted area and click Remove Highlighting.)

Note. When you click Add Note, Books creates highlighting on the selected passage and opens an empty, colored sticky note so you can type in your own annotations. When you click outside the note, it collapses down to a tiny Post-it square in the margin. Click to reopen it.

To delete a note, click the highlighted text. Click Remove Note or Remove Highlight & Note.

Copy copies the highlighted text, ready for pasting in some other program.

In the More menu, a few additional options lurk:

Search Book opens the same search box you’d get by clicking the

icon—except that this time the highlighted word is already filled in, saving you a bit of typing.

icon—except that this time the highlighted word is already filled in, saving you a bit of typing.Search Web, Search Wikipedia hand off the highlighted text to Safari, which searches Google or Wikipedia.

Mail, Messages, Notes opens the share sheet (“Does the file have the correct file name suffix?”) so you can send the highlighted material to somebody else by message or email, or add it to a Notes page.

Speak reads the highlighted passage aloud.

Tip

The Mac’s speaking feature isn’t limited to a blob of text you’ve highlighted. You can use the Edit → Speech → Start Speaking command to have the entire book read to you—in a voice that’s only a little robotic. Yes, this is exactly the feature that debuted in the Amazon Kindle and was then removed when publishers screamed bloody murder—but somehow, so far, Apple has gotten away with it.

Once you’ve added bookmarks, notes, and highlighting to your book, they’re magically and wirelessly synced to any other copies of that book—on other gadgets, like the iPad or iPod Touch, other iPhones, or other Mavericks-or-later Macs. Very handy indeed.

Furthermore, if you click the ![]() button, you’ll see the Notes pane. It presents a tidy list of all your bookmarked pages, notes, and highlighted passages. You can click one of the listings to jump to the relevant page.

button, you’ll see the Notes pane. It presents a tidy list of all your bookmarked pages, notes, and highlighted passages. You can click one of the listings to jump to the relevant page.

Books Settings

If you’ve embraced the simple joy of reading electronic books, then you deserve to know where to make settings changes: in Books → Preferences. Here are the options waiting there.

General tab

Let lines break naturally. Ordinarily, Books presents text with ragged-right margins. Select “Justify text” if you like the text to stretch from edge to edge of the screen.

Auto-hyphenate words. Sometimes, typesetting looks better if hyphens allow partial words to appear at the right edge of each line. Especially if you’ve also turned on “Justify text.”

Display Sleep. If you’ve set your screen to go dark after a period of inactivity (to save power—see “Color Tab”), this checkbox adds a 10-minute grace period to your definition of “inactivity.” The idea is to prevent the screen from going dark just because you’re a slow reader.

Sync. Turn this on if you’d like your bookmarks, highlighting, and book collections to be synced with your other Apple gadgets.

Store tab

See the Note in “Automator”.

Parental tab

If you’re a parent, you might wish to shield your impressionable offspring from dirty reading material—or to shield your credit card from wild teenage book-buying sprees (we should all have that problem!).

Click the ![]() and enter your administrator’s password; now you can turn on “Disable the Book Store” to prevent purchases, or “Restrict books with explicit content” to block the downloading of raunchy material.

and enter your administrator’s password; now you can turn on “Disable the Book Store” to prevent purchases, or “Restrict books with explicit content” to block the downloading of raunchy material.

Advanced tab

This tab offers exactly one control: A checkbox called “Enable Advanced menu in menu bar.” It creates an Advanced menu that itself contains exactly one command: “Add EPUB to Library as Proof.”

This is designed to help one very small group: People who create their own Apple-format ebooks, and wish to look them over on various other Apple gadgets to make sure they look right.

Once you’ve exported your book as an ePub file (from Pages, Adobe InDesign, or some other app), use this command to add it to Books as a finished book. When you open it, use the Devices button at top right to choose an iPhone or iPad you’ve connected to your Mac. (The Books app has to be open on that device.) Presto: Your book gets copied to the other gadget, for your proofreading pleasure. The best part: Each time you make a fix in the ePub document, that change is automatically carried through to the Book versions on the Mac and on iOS.

Calculator

For quick calculations, you don’t need any calculator at all. Just ask Siri: “What’s 17 percent of 300?” or “What’s the square root of 77?” or “What’s 35 times 22?”

Tip

The Spotlight menu is a calculator, too. Type or paste an equation into the Spotlight search box; instantly, the answer appears in the results menu.

If you really need to see the numbers, though, you can use this app, which is much more than a simple four-function memory calculator. It can also act as a scientific calculator for students and scientists, a conversion calculator for metric and U.S. measures, and even a currency calculator for world travelers.

The little Calculator widget in the Today pane of the Notification Center is quicker to open, but the stand-alone Calculator program is far more powerful. For example:

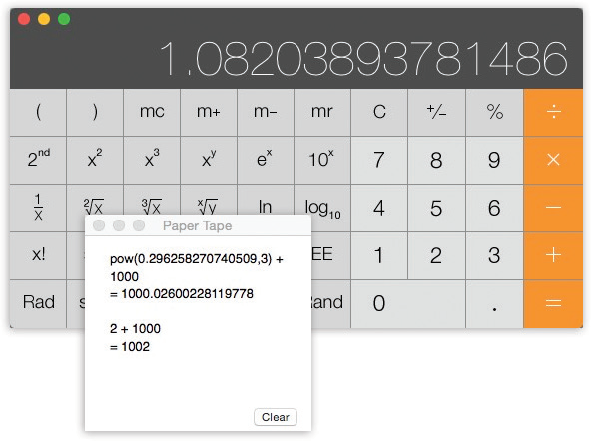

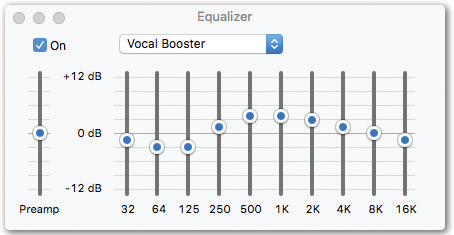

Calculator has three modes: Basic, Scientific, and Programmer (Figure 11-3). Switch among them by choosing from the View menu (or pressing

-1 for Basic,

-1 for Basic,  -2 for Scientific, or

-2 for Scientific, or  -3 for Programmer).

-3 for Programmer).You can operate Calculator by clicking the onscreen buttons, but it’s much easier to press the corresponding number and symbol keys on your keyboard.

As you go, you can make Calculator speak each key you press. The Mac’s voice ensures that you don’t mistype as you keep your eyes on the receipts in front of you, typing by touch.

Just choose Speech → Speak Button Pressed to turn this feature on or off. (You choose which voice does the talking in the Accessibility panel of System Preferences.)

Once you’ve calculated a result, you can copy it (using Edit→Copy, or

-C) and paste it directly into another program.

-C) and paste it directly into another program.Calculator even offers reverse Polish notation (RPN), a system of entering numbers that’s popular with mathematicians, programmers, and engineers, because it lets them omit parentheses. Choose View → RPN Mode, or

-R, to turn it on and off.

-R, to turn it on and off.

Tip

If your Mac has a Touch Bar (“The Complicated Story of the Function Keys”), you can add to it buttons for a few really advanced Calculator functions—Sine, Cosine, Tangent, Random Number, Pi, Hyperbolic Tangent, and many others. Choose View → Customize Touch Bar to get started.

Figure 11-3. The Calculator program offers a four-function Basic mode, a full-blown scientific calculator mode, and a programmer’s calculator (shown here) capable of hex, octal, decimal, and binary notation. The first two modes have a “paper tape” feature (Windows → Paper Tape) that lets you see any errors you may have made way back in a calculation. You can also save the tape as a text file by choosing File → Save Tape As, or print it by selecting File → Print Tape.

Conversions

Calculator is more than a calculator; it’s also a conversion program. No matter what units you’re trying to convert—meters, grams, cubic inches, miles per hour, euros—Calculator is ready.

Now, the truth is, asking Siri to convert units for you, or typing (for example) 35 degrees in centigrade into Spotlight is simpler and quicker to open than this older Calculator feature.

But if you’ve already got Calculator open, here’s the drill: Type in the starting measurement. Then, from the Convert menu, choose the kind of conversion you want (Area, Currency, Temperature, or whatever).

In the dialog box, use the pop-up menus to specify which units you want to convert to and from, and then click OK. There’s your answer!

The next time you want to make this kind of conversion, you can skip steps 2, 3, and 4. Instead, just choose your desired conversion from the Convert → Recent Conversions submenu.

Calculator is especially amazing when it comes to currency conversions—from pesos to American dollars, for example—because it actually goes online to download up-to-the-minute currency rates.

Tip

If you’re working with big numbers, don’t forget to turn on View → Show Thousands Separators. Calculator will add commas (like 1,242,939) to help you read your big numbers more easily.

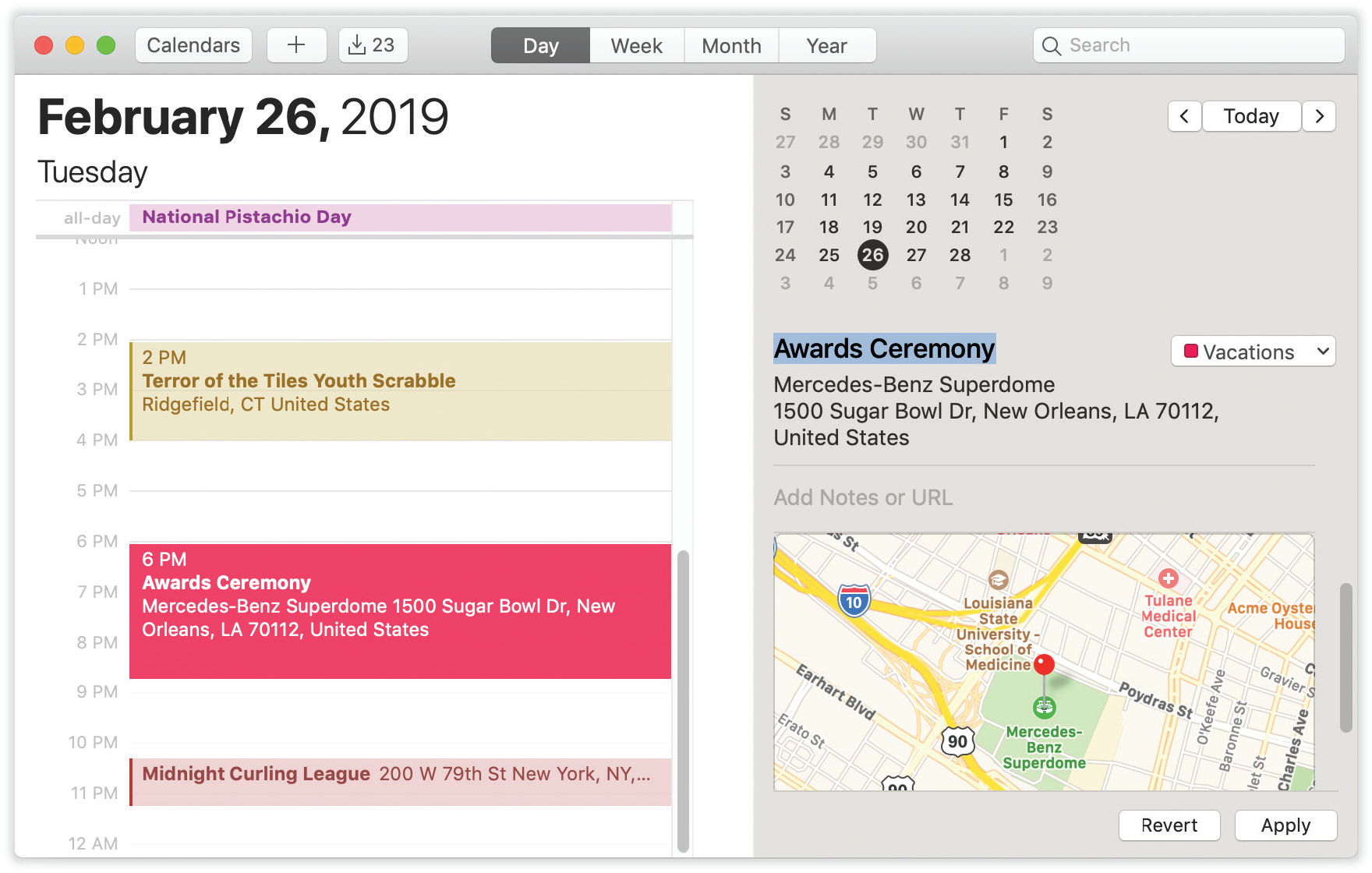

Calendar

The calendar program that was called iCal for many years is now called Calendar, so that it matches its name on the iPhone and iPad.

Calendar is not so different from those “Hunks of the Midwest Police Stations” paper calendars that people leave hanging on the walls for months past their natural life span.

Tip

Calendar’s Dock icon displays today’s date—even when Calendar isn’t running.

But Calendar offers several advantages over paper calendars:

It can automate the process of entering repeating events, such as weekly staff meetings or gym workouts.

Calendar can give you a gentle nudge (with a sound, a dialog box, or even an email) when an important appointment is approaching.

Calendar can share information with Contacts, with Mail, with your iPod/iPad/iPhone, with other Macs, or with “published” calendars on the internet. Some of these features require one of those iCloud accounts described in Chapter 16. But Calendar also works fine on a single Mac, even without an internet connection.

Calendar can subscribe to other people’s calendars. For example, you can subscribe to your spouse’s calendar, thereby finding out when you’ve been committed to after-dinner drinks on the night of the big game. You can also tell Calendar to show your calendars from Google and Yahoo, or even your company’s Exchange calendar.

Working with Views

When you open Calendar, you see something like Figure 11-4. By clicking one of the View buttons above the calendar, or by pressing ![]() -1,

-1, ![]() -2,

-2, ![]() -3, or

-3, or ![]() -4, you can switch among these views:

-4, you can switch among these views:

Day looks exactly like a day-at-a-time desk calendar. On the left side, you see today’s schedule on an hour-by-hour chart. On the right, you see the details of whichever appointment is selected.

If you choose Calendar → Preferences, you can specify what hours constitute a workday. This is ideal both for those annoying power-life people who get up at 5 a.m. for two hours of calisthenics and for the more reasonable people who sleep until 11.

Tip

Calendar provides four quick ways to get to the current day’s date. Click Today (upper-right corner, between the

and

and  ), choose View → Go to Today, or press

), choose View → Go to Today, or press  -T. Or tap Today on the Touch Bar, if your Mac has one.

-T. Or tap Today on the Touch Bar, if your Mac has one.Week fills the main display area with seven columns, reflecting the current week. (You can establish a five-day workweek instead in Calendar → Preferences.)

Tip

If you double-click the date above the calendar, you open the Day view for that day.

Month shows the entire current month. The time of each appointment is listed in gray off to the right of each square.

If a Month-view square is too small to show everything you’ve got scheduled that day, you’ll see a notation at the bottom of the square, like “3 more…” Sometimes, making the window bigger (or full screen) helps make more room, or you can just double-click the date’s number to switch to Day view and see everything at once.

Year view displays the date numbers for the entire year (Figure 11-5).

Figure 11-5. Year view shows the entire year. In Calendar → Preferences → Advanced, you can turn on “Show events in year view,” which actually means “Show me a ‘heat map’ to indicate how hectic my schedule is.”

You can single-click a date number to see a pop-out list of the appointments scheduled for that date.

In Week or Month view, double-click an appointment to see more about it, or even make changes to it.

Tip

In Week or Day view, Calendar sprouts a handy horizontal line that shows where you are in time right now. (Look in the hours-of-the-day “ruler” down the left side of the window to see this line’s little red bulb.) A nice touch, and a handy visual aid that can tell you at a glance when you’re already late for something.

Also, in any view, you can switch into Full Screen mode by clicking the green ![]() button (top left). See “Full Screen Mode” for more on Full Screen mode.

button (top left). See “Full Screen Mode” for more on Full Screen mode.

Tip

Each Calendar view scrolls smoothly and endlessly into the past or future. Day and Week views scroll horizontally; Month and Year views scroll vertically.

Making an Appointment

The basic Calendar is easy to figure out. After all, with the exception of one unfortunate Gregorian incident, we’ve been using calendars successfully for centuries.

Even so, there are two ways to record a new appointment: using the mouse, or using the Quick Event box.

The mousy way

You can quickly record an appointment using any of several techniques, listed here in order of decreasing efficiency:

In Month view, double-click a blank spot on the date you want. Type the name of the event and a time slot—for example, Sales meeting 9am-4:30. (See “The Quick Event way” below for details on how Calendar interprets these time notations.)

In Day or Week view, double-click the starting time to create a one-hour appointment. Or drag vertically through the time slots that represent the appointment’s duration. Either way, type the event’s name inside the newly created colored box.

In Day, Week, or Month view, right-click or two-finger click a date and choose New Event from the shortcut menu. Type the event’s name.

Unless you use the drag-over-hours method, a new event believes itself to be one hour long. But in Day or Week view, you can adjust its duration by dragging the bottom edge vertically. Drag the dark top bar up or down to adjust the start time.

In many cases, that’s all there is to it. You’ve just specified the day, time, and title of the appointment. Now you can get on with your life.

Tip

If the Edit balloon is blocking a part of the calendar you need to see, no biggie: Just drag the balloon out of the way, using any blank spot as a handle. It “tears off” and becomes independent.

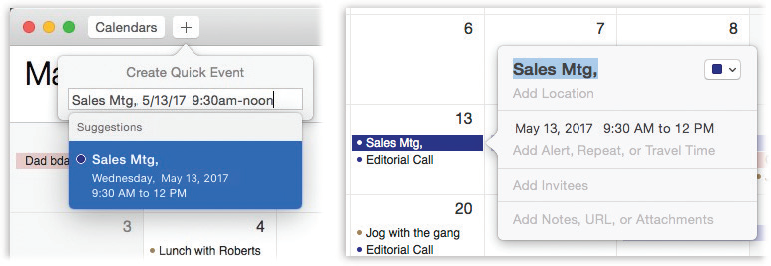

The Quick Event way

In the Quick Event method, the program spares you the trouble of manually selecting dates, start times, and end times. Instead, the program understands notations like “7 pm Friday,” and puts your new appointment into the right time slot automatically.

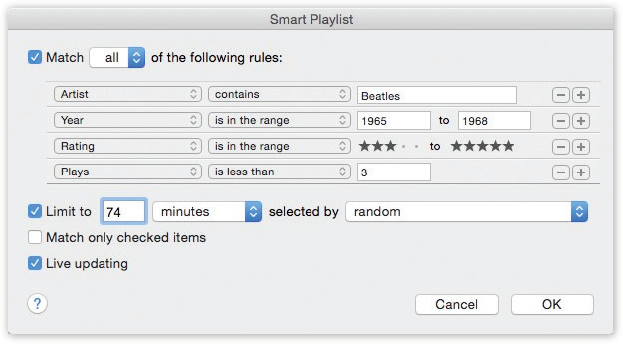

To use this feature, press ![]() -N. Or click + (top left of the window) or choose File → New Event. The Quick Event box appears. Proceed as shown in Figure 11-6.

-N. Or click + (top left of the window) or choose File → New Event. The Quick Event box appears. Proceed as shown in Figure 11-6.

Figure 11-6. Left: Type a plain-English shorthand appointment. Press Return. Marvel as Calendar interprets the times you typed and inserts your meeting into the right time slot.

Note

Calendar proposes adding the new appointment to your default calendar—that is, the category you use most often (read on for details on these calendar categories). Supposedly, you’ve already told it which category is your preferred one by using the Calendar → Preferences → General → Default Calendar pop-up menu.

But as you add a new appointment this way, you can override that setting by holding down the + button. You get a pop-up menu of your calendar categories; only after you click one do you see the Quick Event box shown in Figure 11-6.

Into the Quick Event box, type the name of your appointment and its date and time. For example, you could type Report deadline Aug 12, or “Titanic 2: The Return” Sat 7 pm, or Cara date 11-11:15am. When you press Return, Calendar interprets what you typed, using these rules:

If you didn’t specify an ending time, Calendar sets the appointment to one hour.

If you didn’t enter any time information, Calendar just schedules your event for all day.

If you typed breakfast or morning, Calendar sets the appointment to start at 9 a.m.; lunch or noon, it starts at 12 p.m.; dinner or night, it starts at 7 p.m.

If you enter a weekday (for example, Chicago Monday), Calendar assumes you mean the very next occurrence of that day. (If that’s not what you want, enter the date, like Chicago Jul 3.)

If you enter a time but not a date or day (for example, Fishing 3:30 pm), Calendar assumes you mean today.

The Quick Event system has a feature that saves you time and typos: As you type, Calendar displays a menu of similar appointments you’ve entered in the past (Figure 11-6, left). If you click one, Calendar fills in all the details of the new appointment in one fell swoop, copying them from the earlier event.

As soon as Calendar interprets your shorthand and turns it into a real appointment, its details balloon opens automatically (Figure 11-6, right), so you can clean up any errors and add more details.

Location, alarms, travel time, and other details

No matter which method you use to create the basic event (the mouse way or the Quick Event way), you’re now presented with the information balloon shown at right in Figure 11-6. Here’s where you go to town filling in the details. (This same balloon will appear when you double-click any existing appointment later.)

Tip

You can also open the Info balloon by clicking an appointment and then pressing ![]() -E (which is short for Edit → Edit Event).

-E (which is short for Edit → Edit Event).

For each appointment, you can tab your way to the following information areas:

subject. That’s the large, bold type at the top—the name of your appointment. For example, you might type Fly to Phoenix.

calendar. A calendar, in Calendar’s terminology, is a subset—a category—into which you can place appointments. You can create one for you, one for family-only events, one for book-club appointments, and so on. You can hide and show these categories at will. Details begin in “Searching for events”; for now, note that the tiny colored square in the top-right corner of the Info bubble is a pop-up menu of your calendars.

Tip

Use this same pop-up menu to change an appointment’s category. If you filed something in “Company Memos” that should have been in “Sweet Nothings for Honey-Poo,” then open the event’s information balloon and reassign it. Quick.

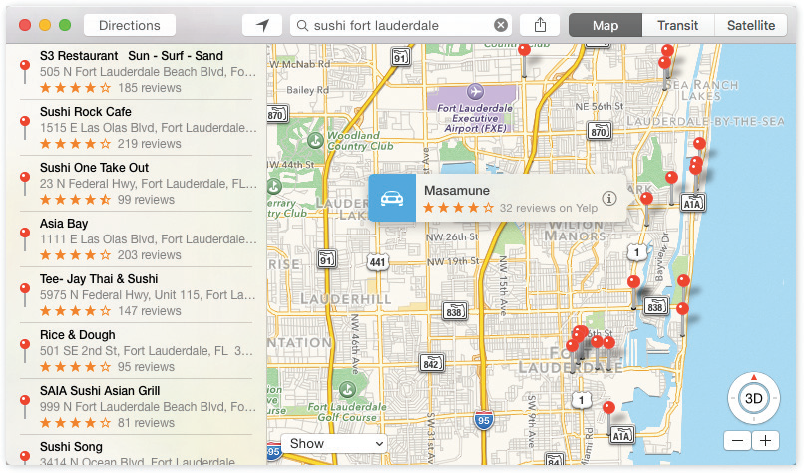

location. This field makes a lot of sense; almost everyone needs to record where a meeting is to take place. You might type a reminder for yourself like My place, a specific address like 212 East 23rd, or some other helpful information, like a contact phone number or flight number.

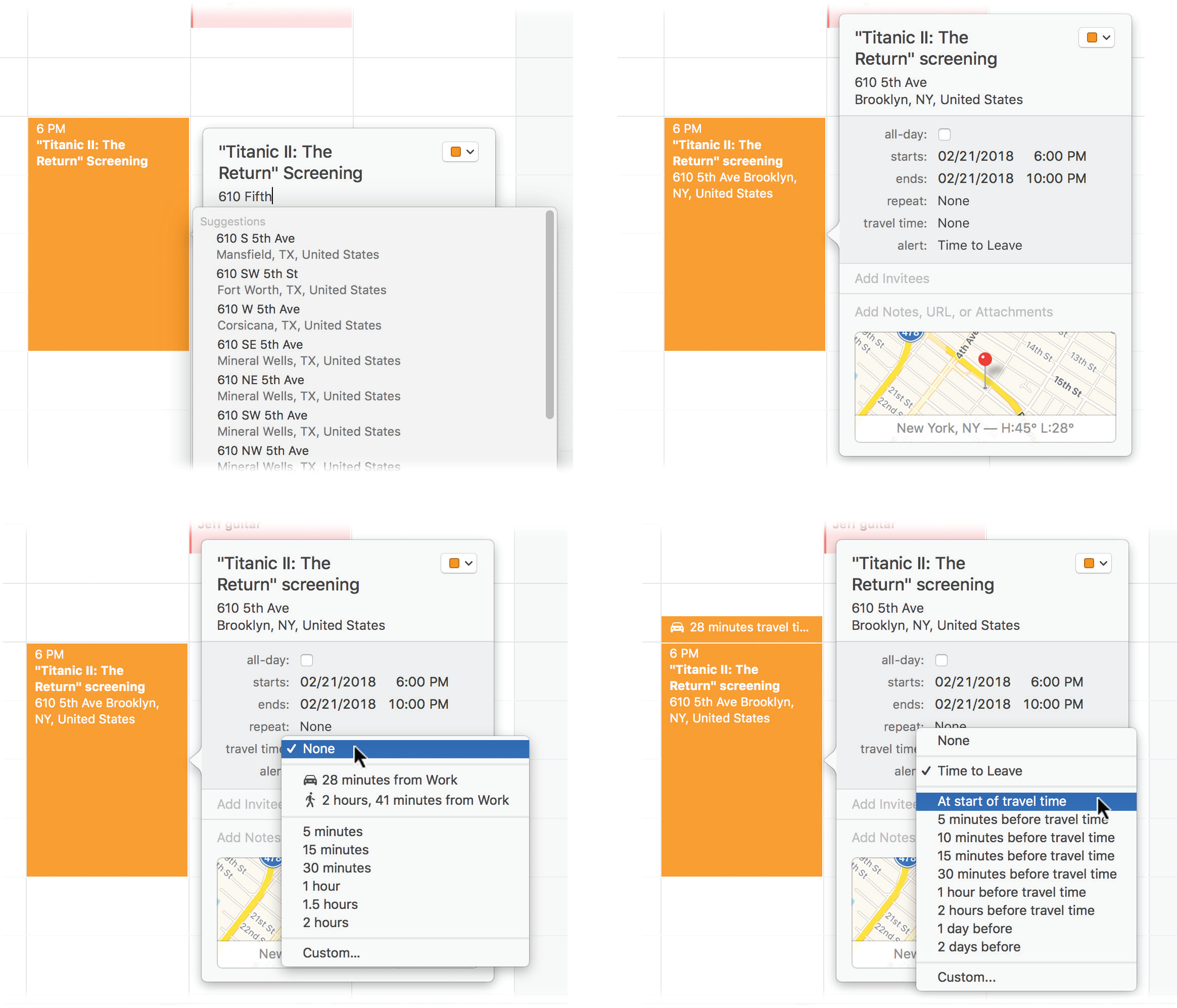

As you type, Calendar busily consults Apple’s worldwide database of street addresses—and proposes a few matches, as shown in Figure 11-7 (top left). You’re under no obligation to choose one of these; you can ignore the suggestions and type “Casey’s treehouse,” for all Apple cares. But if you do choose from Apple’s list of proposals, some cool things happen.

Figure 11-7. Here’s the life cycle of Calendar’s location and travel-time feature.

Top left: To make the travel-time calculation work, you must choose from Calendar’s list of location suggestions, based on what you’ve typed.

Top right: You get a map and weather report for that location.

Bottom left: Calendar knows how long it will take to get there…

Bottom right: …and will remind you when it’s time to get going!For example, you get a little map (which you can click to open the Maps app for a bigger view), as shown in Figure 11-7 (top right). You get to see the current weather, so you know how much to bundle up. And you get to use the travel-time feature described on the facing page.

Note

The next few controls appear only when you expand the Info bubble to see the time and date information. To do that, click whatever time is listed now—or, if you’ve just tabbed your way to the times, press Return.

all-day. An “all-day” event, of course, refers to something that has no specific time of day associated with it: a holiday, a birthday. When you turn on this box, you see the name of the appointment jump to the top of the Calendar screen, in the area reserved for this kind of thing.

starts, ends. You can adjust the times shown here by typing, clicking buttons, or both. Press Tab to jump from one setting to another, and from there to the hours and minutes of the starting time.

Note

The little calendar that pops up when you click the date is handier than typing a date manually.

For example, start by clicking the hour, and then increase or decrease this number either by pressing

and

and  or by typing a number. Press Tab to highlight the minutes and repeat the arrow-buttons-or-keys business. Finally, press Tab to highlight the AM/PM indicator, and type either A or P—or press

or by typing a number. Press Tab to highlight the minutes and repeat the arrow-buttons-or-keys business. Finally, press Tab to highlight the AM/PM indicator, and type either A or P—or press  or

or  —to change it, if necessary.

—to change it, if necessary.Tip

If you specify a different ending date, then a banner appears across the top of the calendar.

time zone. This option appears only after you choose Calendar → Preferences → Advanced and then turn on “Turn on time zone support.” And you would do that only if you plan to be traveling on the day this appointment comes to pass.

Once you’ve done that, a time zone pop-up menu appears. It starts out with “America/New York” (or whatever your Mac’s usual time zone is); if you choose Other, then a tiny world map appears. Click the time zone that represents where you’ll be when this appointment comes due. From the shortcut menu, choose the major city that’s in the same time zone you’ll be in.

Tip

The time zone pop-up menu remembers each new city you select. The next time you travel to a city you’ve visited before, you won’t have to do that clicking-the-world-map business.

Now, when you arrive in the distant city, use the time zone pop-up menu at the top-right corner of the Calendar window to tell Calendar where you are. You’ll see all of Calendar’s appointments jump, like magic, to their correct new time slots.

repeat. The pop-up menu here contains common options for recurring events: every day, every week, and so on. It starts out saying None.

Once you’ve made a selection, you get an end pop-up menu that lets you specify when this event should stop repeating. If you choose “Never,” then you’re stuck seeing this event repeating on your calendar until the end of time (a good choice for recording, say, your anniversary, especially if your spouse might be consulting the same calendar). You can also turn on “After [a certain number of times],” which is a useful option for car and mortgage payments. And if you choose “On date,” you can specify the date when the repetitions come to an end; use this option to indicate the last day of school, for example.

“Custom” lets you specify repeat schedules like “First Monday of the month” or “Every two weeks.”

Tip

If you don’t see the following items in the editing bubble, then click the gray lettering that says “Add Alert, Repeat, or Travel Time” to make them appear.

travel time. This item represents a breakthrough in common sense: It automatically builds travel time into Calendar’s understanding of any appointment. After all, it’s not very useful to get a reminder like “Lunch with Jenkins at 1 p.m.” 10 minutes beforehand if it takes half an hour to get there.

Now, then: If Calendar is to calculate travel time, it has to know where you’re starting out and where you’re going.

To figure out your starting point, the Mac consults your “me” card in the Contacts app (“More Anti-Spam Tips”), and uses either your home address or your work address, depending on the time of day. (How does Calendar know when you’re at work? It cleverly uses the “Day starts at” and “Day ends at” settings in Calendar → Preferences → General.)

If you haven’t specified home and work addresses on your “me” card, then Calendar uses the current location of your Mac as the starting point. (And that works only if you’ve allowed the Mac to track your location; see “Finding Yourself”.)

For the arrival location, the travel-time feature requires that you’ve accepted one of the Mac’s address suggestions, as described in Figure 11-7, top left.

Once all that’s done, the travel-time pop-up menu shows you both the driving and walking times to your appointment. You can override these suggestions if you like; you can choose any time interval from five minutes to two hours, or choose Custom to plug in something not listed here.

The real payoff, of course, comes when you set a reminder for yourself; read on.

alert. This pop-up menu tells Calendar to notify you when a certain appointment is about to begin. Choose how much notice you want: “At time of event,” “5 minutes before,” all the way up to “2 days before.” If it’s a TV show, a reminder five minutes before airtime is fine. If it’s a birthday, you might set up a two-day warning, so there’s time to buy a present.

Actually, you can get a lot more particular than that. If you choose Custom, you can specify any advance-warning interval at all: “16 minutes before,” or “15 days after,” or whatever. (Yes, you can even set up an alarm to ring after the event—great if you want to follow up with something or check the oven.)

Here in Customland, you can also set any of three kinds of flags to get your attention. Calendar can display a message (with a sound, if you like), send you an email, or open a file on your hard drive. (You could use this unusual option to ensure that you don’t forget a work deadline by having Calendar fling the relevant document open in front of your face at the eleventh hour.)

And if you’ve used the travel-time feature already described, Calendar offers choices related to the travel time, such as “at start of travel time” or 5, 15, or 30 minutes before, which may be helpful if you need to plot time for showering. (Figure 11-7, lower right).

Tip

You can set up more than one alarm for the same appointment, each with its own advance-warning interval. Just click the + button to add a new one.

show as (busy/free/tentative/out of office). This little item shows up only if you’ve subscribed to a calendar server, like an internet-based calendar (in geek-speak, a CalDAV server) or your company’s Exchange calendar. It communicates to your colleagues when you might be available for meetings.

Note

If your calendar comes from a CalDAV server, then your only options are “busy” and “free.” The factory setting for most appointments is “busy,” but for all-day events it’s “free.” Which is logical; just because it’s International Gecko Appreciation Day doesn’t mean you’re not available for meetings (rats!).

You might think: “Well, duh—if I’ve got something on the calendar, then I’m obviously busy!” But not necessarily. Some Calendar entries might just be placeholders, reminders to self, TV shows you wanted to watch, appointments you’d be willing to change—not things that would necessarily render you unavailable if a better invitation should come along.

Add Invitees. If the appointment is a meeting or some other gathering, you can type the participants’ names here. If a name is already in your Contacts program, then Calendar proposes autocompleting the name for you.

If you separate several names with commas, Calendar automatically turns each into a shaded button. You can click it for a pop-up menu of commands like Remove Attendee and Send Email. (That last option appears only if the person in Contacts has an email address, or if you typed a name with an email address in brackets, like this: Chris Smith <[email protected]>.)

Tip

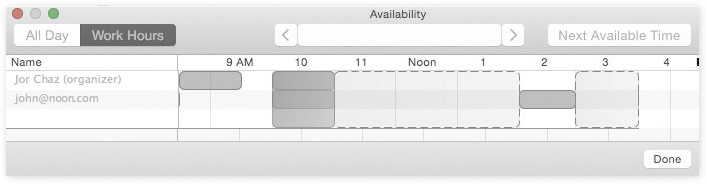

If you and your invitees are on the same CalDAV or Exchange calendar service—usually, co-workers at the same company—Calendar can show a “time map” of the invitees’ days, all in a handy scrolling window, so you can find a time when everybody’s free. To see this map, click the Available Meeting Times link beneath the addresses of the invitees you’ve specified, or choose Window → Availability Panel (see Figure 11-8).

Figure 11-8. Drag the vertical block (your proposed meeting) to a different time slot, or click Next Available Time to find when everybody’s free. Good luck.

Once you’ve specified some attendees, a Send button appears in the Info box. If you click it, Calendar fires up Mail and prepares ready-to-send messages, each with an .ics attachment: a calendar-program invitation file. See the box on the facing page.

Add Notes, URL or Attachments. You can type, paste, or drag any text you like in the note area—driving directions, contact phone numbers, a call history, or whatever.

Your newly scheduled event now shows up on the calendar, complete with the color coding that corresponds to the calendar category you’ve assigned.

What to Do with an Appointment

Once you’ve entrusted your agenda to Calendar, you can start putting it to work. Calendar is only too pleased to remind you (via pop-up messages) of your events, reschedule them, print them out, and so on. Here are a few of the possibilities.

Editing events

To edit a calendar event’s details, click to open its Info balloon (Figure 11-6).

And if you want to change only an appointment’s “calendar” category, right-click or two-finger click anywhere on the appointment and choose from the resulting Calendar shortcut menu. That way, you bypass the need to open the Info balloon.

Rescheduling events

If an event in your life gets rescheduled, you can drag an appointment block vertically in a Day- or Week-view column to make it later or earlier the same day, or horizontally to another date in any view. (If you reschedule a recurring event, Calendar asks if you want to change only this occurrence, or this and all future ones.)

If something is postponed for, say, a month or two, you can grab it in the Month view and drag it down as the months very slowly scroll by. Or you can open the Info balloon and edit the starting and ending dates or times—or just cut and paste the event to a different date.

Lengthening or shortening events

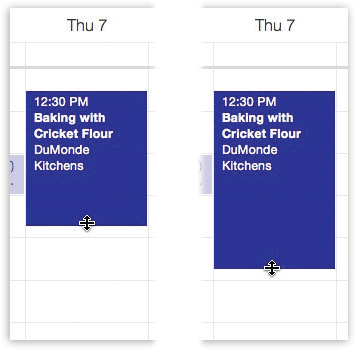

If a scheduled meeting becomes shorter or your lunch hour becomes a lunch hour-and-a-half (in your dreams), changing the length of the representative calendar event is as easy as dragging the bottom border of its block in any column view (see Figure 11-9).

Tip

In Week view, if you’ve grabbed the bottom edge of an appointment’s block so that the cursor changes, you can drag horizontally to make an appointment cross the midnight line and extend into a second day.

Figure 11-9. You can resize any Calendar event just by dragging its bottom border. As your cursor touches the bottom edge of an event, it turns into a double-headed arrow. You can now drag the event’s edge to make it take up more or less time on your calendar.

Printing events

To commit your calendar to paper, choose File → Print, or press ![]() -P. The resulting Print dialog box lets you include only a certain range of dates, only events on certain calendars, with or without To Do lists or mini-month calendars, and so on.

-P. The resulting Print dialog box lets you include only a certain range of dates, only events on certain calendars, with or without To Do lists or mini-month calendars, and so on.

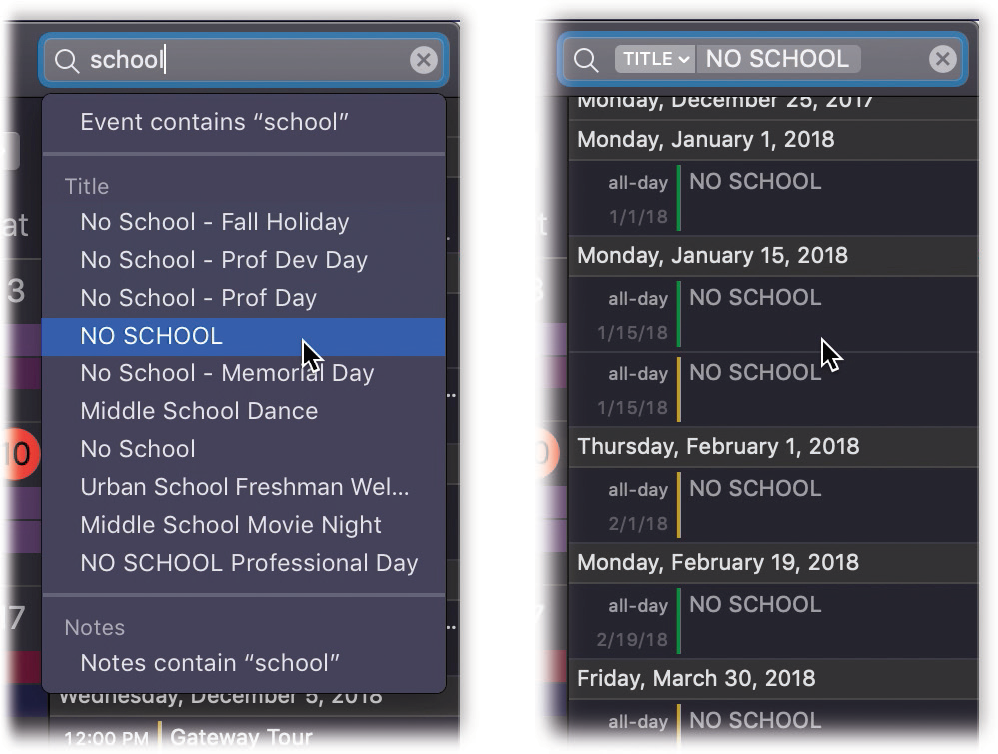

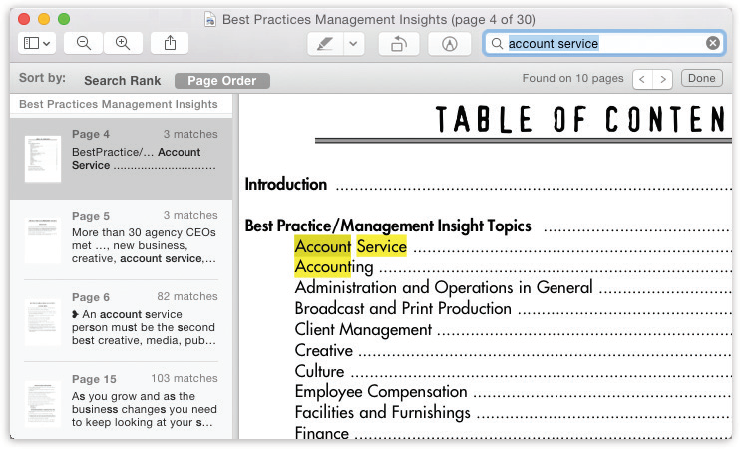

Searching for events

When you type into the search box at the top right of the Calendar screen, you’re offered some “search tokens” that indicate where you want to search for that phrase (in the name of an event, in its notes, location, and so on). The right-hand column offers a clickable list of search results. Figure 11-10 has the details.

Figure 11-10. Left: Type into the search box; Calendar sprouts a list of suggestions (“Event contains ‘school,’ ” “Notes contain ‘school,’ ” and so on).

Right: Click one to create a search token exactly like the ones that Spotlight and Mail use. They let you build up complex searches, bubble by bubble. Double-click any row of the list to jump to the corresponding event on the calendar and open up its summary balloon.

Deleting events

To delete an appointment, click it and then press the Delete key. If you delete a recurring event (like a weekly meeting), Calendar asks whether you want to delete only that particular instance of the event, or the whole series from that point forward.

The “Calendar” Category Concept

Calendar has calendars that let you organize appointments into subsets. One person might have calendars called Me, Spouse ’n’ Me, and Whole Family. A small business could have categories called Deductible Travel, R&D, and R&R.

And now, the Calendar Tip-O-Rama:

To create a calendar, choose File → New Calendar. You now have to specify where you want this category to live: On My Mac (meaning on your Mac), or on one of your online accounts, like iCloud, Google, Yahoo, or Exchange. Type a name that defines the category in your mind.

Note

When you set up an iCloud account either in System Preferences or when you first run macOS, Calendar automatically transfers your On My Mac categories to iCloud. You can no longer create categories that live only on your Mac. (There’s one exception: If you created your iCloud account in Calendar Preferences, then you can have an On My Mac category.)

To see your list of categories, click the Calendars button (upper left of the window). A Sidebar list appears, if it wasn’t already open.

Hide or show an entire category of appointments at once by turning on or off the appropriate checkbox in the Calendars Sidebar.

To change the color of a category, right-click or two-finger click its name in the Sidebar list. In the pop-up bubble, you choose a new color.

To specify your default calendar, choose Calendar → Preferences → General. Choose from the Default Calendar pop-up menu. (The Default calendar is the category that every new appointment falls into unless you change it. It’s also the category that other apps‚ like Mail, propose putting new appointments into.)

To assign a new appointment to a calendar, click the color swatch in the corner of its Info balloon.

To change an appointment’s calendar category, right-click or two-finger click the appointment’s name and choose a calendar name from the shortcut menu.

You may be able to make calendar groups, too. Those are containers that consolidate the appointments from several other calendars. For example, you could have a calendar group called Kids, containing the individual calendars for each of your offspring. Super-calendars like this make it easier to manage, hide, show, print, and search subsets of your appointments. (Sadly, this feature is available only for On My Mac categories, as described previously—not for online accounts.)

To create a calendar group, choose File → New Calendar Group. Name the resulting item in the Calendar list; for the most part, it behaves like any other calendar. Drag other calendar names onto it to include them. Click the flippy triangle to hide or show the component calendars.

“Publishing” Calendars to the Web

One of Calendar’s best features is its ability to post your calendar on the web, so that other people can subscribe to it, which adds your appointments to their calendars. Anyone with a web browser—or only people you designate—can also view your calendar, right online.

For example, you might use this feature to post the meeting schedule for a club that you manage, or to share the agenda for a series of upcoming financial meetings that all your co-workers will need to consult.

Publishing

The steps for sharing a calendar depend on whether or not you have an iCloud account. Observe:

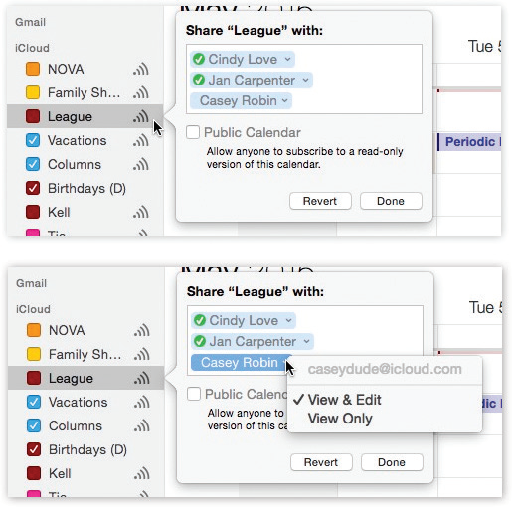

If you have an iCloud account: Proceed as shown in Figure 11-11. Note that you can specify whether each person can just see the appointments or be able to edit them, too. That’s a delightful, two-way collaboration—a terrific way for a couple or a family to coordinate everyone’s calendars, for example.

Behind the scenes, Calendar sends an invitation to the recipient. If she has a Mac, iPhone, or iPad, she’ll see a notification right in Calendar (![]() ); otherwise, she’ll get the invitation by email. Once she clicks the invitation and clicks Accept, your shared calendar shows up on her machine.

); otherwise, she’ll get the invitation by email. Once she clicks the invitation and clicks Accept, your shared calendar shows up on her machine.

Later you can modify the settings (Figure 11-11, bottom). Or you can stop sharing with someone by clicking the ![]() next to a calendar name, clicking a person’s name, and then pressing the Delete key.

next to a calendar name, clicking a person’s name, and then pressing the Delete key.

Tip

You can also share an iCloud calendar at icloud.com. Just click the ![]() icon beside a calendar’s name.

icon beside a calendar’s name.

Figure 11-11. Top: Point to the name of the iCloud calendar you want to publish; click the “share” icon ( ) that appears next to its name.

) that appears next to its name.

In the pop-out panel, enter the email address of the lucky recipient (it must be someone you’ve entered into your Contacts). You can invite several; just keep entering addresses.

The Public Calendar option means that the whole internet can see this calendar category (if they know the secret URL).

Bottom: Use the  to specify whether a person can see your appointments (View Only) or make changes to them, too (View & Edit).

to specify whether a person can see your appointments (View Only) or make changes to them, too (View & Edit).

After the recipient has accepted the invitation, click the  icon again; this time, a green checkmark appears next to the person’s name.

icon again; this time, a green checkmark appears next to the person’s name.

If you don’t have an iCloud account: If you don’t have iCloud, then you’ll need a website of your own, where your online calendar can be hung. And it has to be a WebDAV-compatible server (ask your web-hosting company). You know what? It might just be easier to sign up for a free iCloud account and do it that way.

In any case, begin by making sure that the Calendars list is open. Click the calendar you want to share. Choose Edit → Publish Calendar. (This command doesn’t appear if you have an iCloud account, since the sharing mechanism is so much simpler with iCloud.)

Tip

You have to perform this step individually for each calendar category. If you want to publish more than one calendar simultaneously, then create a calendar group, and publish that.

A dialog box appears. This is where you specify your web address, its password (if necessary), and how your saved calendar is going to look and work. If you turn on “Publish changes automatically,” then whenever you edit the calendar, Calendar connects to the internet and updates the copy there. (Otherwise, you can right-click or two-finger click the calendar’s name and choose Refresh whenever you want to update the web copy.)

When you click Publish, your Mac connects to the web and then shows you the web address (the URL) of the finished page, complete with a Send Mail button that lets you fire the URL off to your colleagues.

Tip

Whenever you want to send someone the subscription information, click the calendar category you’ve published and choose Edit → Send Publication Email. Calendar will prepare an outgoing email message containing details on subscribing to your calendar.

To stop publishing that calendar, click its name in the Calendars pop-up list and then choose Edit → Stop Publishing.

Subscribing

Often, websites publish calendars that you can bring into Calendar. Maybe you use TripIt.com to manage your flights and hotel reservations. Maybe you’ve found a calendar you like at icalshare.com—a schedule of rocket launches, trade shows, National Hockey League games, NASCAR races, soccer matches, the Survivor TV show, holidays, or whatever.

Each of these web calendars has its own address. To subscribe, choose File → New Calendar Subscription. In the Subscribe to Calendar dialog box, paste the address of the published calendar.

You can also provide your own name for this category, specify how often you want your own copy to be updated (assuming you have a full-time internet connection), and indicate whether or not you want to be bothered with the publisher’s alarms and notes.

When it’s all over, you see a new “calendar” category in your left-side list, representing the published appointments.

Google, Yahoo, and Facebook Calendars

If you maintain a calendar online—at Google, Yahoo, or Facebook, for example—you may take particular pleasure in discovering how easy it is to bring those appointments into Calendar. It’s one handy way to keep, for example, a husband’s and wife’s appointments visible on each other’s calendars.

Setting this up is ridiculously easy. Choose Calendar → Preferences → Accounts. Click + below the list. Enter your Google, Yahoo, or Facebook address (for example, [email protected]) and password. Click Create.

In a minute or so, you’ll see all your Google, Yahoo, or Facebook events show up in Calendar. (Each web calendar has its own heading in the left-side list.) Better yet: It’s a two-way sync; changes you make to these events in Calendar show up on the web, too.

Syncing Calendar with Your iPhone, iPad, and Other Computers

Here’s the real magic of Calendar, iCloud, and the rest of Apple’s software archipelago: Your calendar can be autosynced among all your machines, like your iPhone, iPad, and Macs. Add an appointment on your phone, change an appointment on your iPad, whatever—all your other gadgets are wirelessly and automatically synced to match. See “Meet iCloud” for details on this amazing setup.

Note

Wondering where the To Do list feature went? It was in iCal, but it’s gone in Calendar. That’s because macOS has its own full-blown Reminders app now, described later in this chapter.

Chess

MacOS comes with only one game, but it’s a beauty (Figure 11-12). It’s a traditional chess game played on a gorgeously rendered board with a set of realistic 3D pieces.

Note

The program is actually a sophisticated Unix-based chess program, Sjeng, that Apple packaged up in a new wrapper.

Figure 11-12. You don’t have to be terribly exact about grabbing the chess pieces when it’s time to make your move. Just click anywhere within a piece’s current square to drag it into a new position on the board (shown here in its Wood incarnation). And why is this chessboard rotated like this? Because you can grab a corner of the board and rotate it in 3D space. Cool!

Playing a Game of Chess

When you launch Chess, you’re presented with a fresh, new game that’s set up in Human vs. Computer mode—meaning that you, the Human (light-colored pieces) get to play against the Computer (your Mac, on the dark side). Drag the chess piece of your choice into position on the board, and the game is afoot.

If you choose Game → New, however, you’re offered a pop-up menu with choices like Human vs. Computer, Human vs. Human, and so on. If you switch the pop-up menu to Computer vs. Human, then you and your Mac trade places; the Mac takes the white side of the board and opens the game with the first move, and you play the black side.

Tip

The same New Game dialog box also has a pop-up menu called Variant, which offers three other chess-like games: Crazyhouse, Suicide, and Losers.

On some night when the bowling alley is closed and you’re desperate for entertainment, you might also want to try the Computer vs. Computer option, which pits your Mac against itself. Pour yourself a beer, open a bag of chips, and settle in to watch until someone—either the Mac or the Mac—gains victory.

Chess Prefs

Choose Chess → Preferences to find some useful controls like these:

Style. Apple has gone nuts with the computer-generated materials options in this program. You can choose all kinds of wacky materials for the look of your game board (Wood, Metal, Marble, or Grass) and for your playing pieces (Wood, Metal, Marble, or Fur).

Computer Plays. Use this slider to determine how frustrated you want to get when trying to win at Chess. The farther you drag the slider toward the Stronger side, the more calculations the computer runs before making its next move—and, thus, the harder it gets for you to outthink it. At the Faster setting, Chess won’t spend more than five seconds ruminating over possible moves. Drag the slider all the way to the right, however, and the program may analyze each move for as long as 10 fun-filled hours. This hardest setting, of course, makes it all but impossible to win a game (which may stretch on for a week or more anyway).

Speech. The two checkboxes here let you play Chess using the Mac’s built-in voice-recognition features, telling your chess pieces where to go instead of dragging them, and listening to the Mac tell you which moves it’s making. See “Speech”.

Tip

If your Chess-playing skills are less than optimal, the Moves menu will become your fast friend. The three commands there undo your last move (great for recovering from a blunder), suggest a move when you’re stuck, and display a previous move (in case you failed to notice what the computer just did).

Studying Your Games

You can choose Game → Save to save any game in progress, so you can resume it later.

To analyze the moves making up a game, use the Moves → Game Log command, which displays the history of your game, move by move. A typical move would be recorded as “Nb8 – c6,” meaning the knight on the b8 square moved to the c6 square. With a Chess list document, you could recreate an entire game, move by move.

Contacts

Here’s the old Address Book program, now renamed so that it matches the iPhone and iPad versions. See “More Anti-Spam Tips” for details.

Dashboard

Dashboard, described in Chapter 5, is a true-blue, double-clickable application. As a result, you can remove its icon from your Dock, if you like.

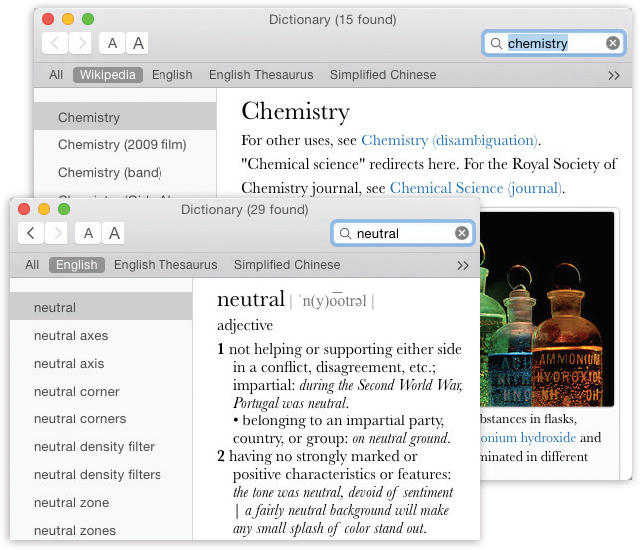

Dictionary

For word nerds everywhere, the Dictionary is a blessing—a handy way to look up word definitions, pronunciations, and synonyms (Figure 11-13). To be precise, macOS comes with electronic versions of multiple reference works in one.

Figure 11-13. When you open the Dictionary, it generally assumes you want a word’s definition (lower left). If you prefer to see the Wikipedia entry (top right) at startup time instead, for example, choose Dictionary → Preferences—and drag Wikipedia upward so that it precedes New Oxford American Dictionary. That’s all there is to it!

The entire New Oxford American Dictionary. The third edition, actually. You’ll note that its entries give you more examples, background, and tables that help to differentiate fine shades of meaning (look up weak for an example).

The complete Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus.

Two venerable guides to British English: the Oxford Dictionary of English and Oxford Thesaurus of English.

A dictionary of Apple terms, from “access control lists” to “Yosemite.”

Wikipedia. This famous citizen-created encyclopedia isn’t actually on your Mac. Dictionary just gives you an easy way to search the online version, and display the results right in the comfy Dictionary window.

Foreign language dictionaries: You also get Japanese, French, Spanish, German, Dutch, Korean, Italian, Chinese, Hindi, Norwegian, Swedish, Portuguese, Russian, Turkish, Thai, Hebrew, and Danish—plus English translation dictionaries for Arabic, Hindi, French, German, Dutch, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, Russian, Japanese, Korean, and Chinese.

Note

You don’t ordinarily see these reference books. You have to turn them on in Dictionary → Preferences.

MacOS also comes with about a million ways to look up a word:

Search it in Spotlight. Press

-space, type the word you want into the Spotlight search box, and marvel as the dictionary entry appears at the bottom of the results list. To read the definition, click it once.

-space, type the word you want into the Spotlight search box, and marvel as the dictionary entry appears at the bottom of the results list. To read the definition, click it once.If you have a trackpad, point to a word in a basic Mac program, and then double-touch the trackpad (don’t actually click) with three fingers. That’s the gesture for the same dictionary panel already described. (It doesn’t work unless you’ve turned it on in System Preferences → Trackpad.)

Double-click the Dictionary icon. You get the window shown at bottom in Figure 11-13. As you type into the Spotlight-y search box, you home in on matching words; click a word, or highlight it and press Return, to view a full, typographically elegant definition, complete with sample sentence and pronunciation guide.

Tip

And if you don’t recognize a word in the definition, click that word to look up its definition. (Each word turns blue and underlined when you point to it, as a reminder.) You can then click again in that definition—and on and on and on.

(You can use the

and

and  buttons on the toolbar, or the

buttons on the toolbar, or the  -[ and

-[ and  -] keystrokes to go back and forward in your chain of lookups. Hold down the

-] keystrokes to go back and forward in your chain of lookups. Hold down the  for a pop-up menu of recent lookups.)

for a pop-up menu of recent lookups.)It’s worth exploring the Dictionary → Preferences dialog box, by the way. There you can choose U.S. or British pronunciations and adjust the font size.

Press

. Yes, the Dictionary is one of the widgets in the Dashboard (“Dashboard”).

. Yes, the Dictionary is one of the widgets in the Dashboard (“Dashboard”).Right-click or two-finger click a highlighted word in a Cocoa program. From the shortcut menu, choose Look Up [word]. You get a panel that pops out of the highlighted word, showing the Dictionary page for that word.

Use the dict:// prefix in Safari. This might sound a little odd, but it’s actually ultra-convenient, because it puts the dictionary right where you’re most likely to need it: on the web.

Turns out that you can look up a word (for example, preposterous) by typing dict://preposterous into the address bar. When you hit Return, Dictionary opens automatically and presents the search results from all its resources (dictionary, thesaurus, Apple terms, and Wikipedia).

Point to a word in a basic Mac program, and then press Control-

-D. That keystroke makes the definition panel sprout right from the word you were pointing to. (The advantage here, of course, is that you don’t have to highlight the word first.) “Basic Mac program,” in this case, means one of the Apple standards: Mail, Stickies, Safari, TextEdit, Messages, and so on.

-D. That keystroke makes the definition panel sprout right from the word you were pointing to. (The advantage here, of course, is that you don’t have to highlight the word first.) “Basic Mac program,” in this case, means one of the Apple standards: Mail, Stickies, Safari, TextEdit, Messages, and so on.

The front matter of the Oxford American Dictionary (the reference section at the beginning) is here, too. It includes some delicious writers’ tools, including guides to spelling, grammar, capitalization, punctuation, chemical elements, and clichés, along with the full text of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. Just choose Go → Front/Back Matter—and marvel that your Mac comes with a built-in college English course.

Tip

Got a big screen or poor eyesight? Then bump up the type size. Dictionary’s toolbar has bigger/smaller buttons, and there’s a Font Size pop-up menu in the Preferences window.

DVD Player

If you’re one of the few, the proud, who own a DVD drive, you can play back DVD movies using macOS’s aging but perfectly functional DVD Player app.

FaceTime

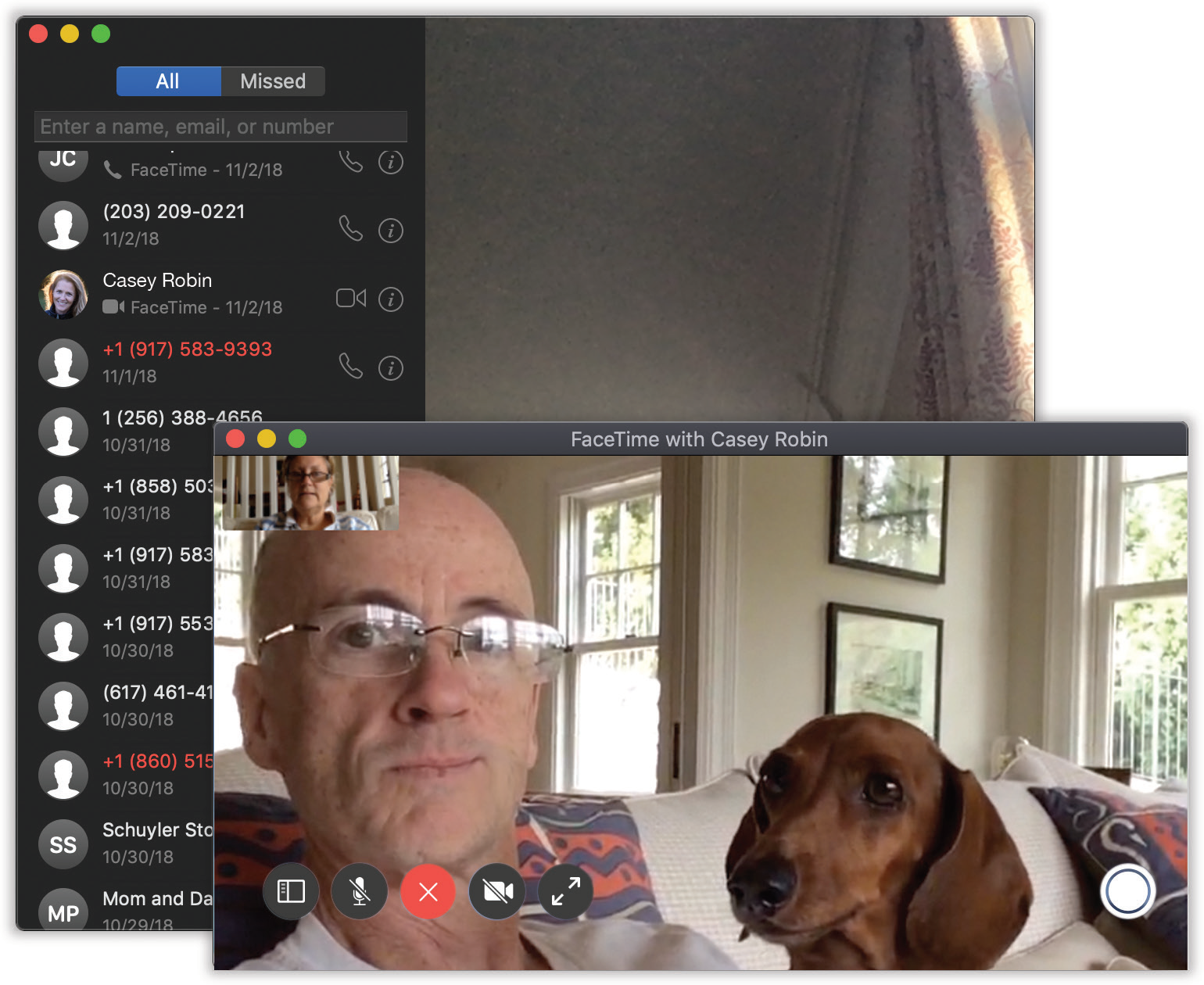

If you have a Mac laptop or an iMac, then it’s got a built-in microphone and camera. And that means it’s equipped to make free, very high-quality audio and video calls to other Apple computers, phones, and tablets (Figure 11-14). In macOS Mojave 10.14.1 and later, in fact, it can make group video calls, with as many as 32 people on the screen at once.

There’s very little delay, and it works the first time and every time. Now Grandma can see the baby, or you can help someone shop from afar, or you can supervise brain surgery from thousands of miles away (medical training recommended).

From your Mac, you’ll probably make FaceTime calls over a Wi-Fi network. But your callees, using iPhones or cellular iPads, can even conduct video chats over the cellular airwaves, when they’re out and about.

Figure 11-14. Yes, Messages also offers video calls—but FaceTime doesn’t need as fast an internet connection. You’ll often be able to make FaceTime video calls in situations when Messages gives up.

Placing a Call

The FaceTime experience often begins with a more old-fashioned communication—a phone call or a text message, for example. (“Want to FaceTime now?”)

In any case, FaceTime couldn’t be easier to fire up—in many different ways:

From Contacts. If you’re in the Contacts app, and you’ve recorded the iPhone number or Apple ID of someone in your Mac’s Contacts program, you’ll see the

button next to that person’s name. Click it to place a video call. Or, to place an audio call, click

button next to that person’s name. Click it to place a video call. Or, to place an audio call, click  , and then click FaceTime Audio.

, and then click FaceTime Audio.From the FaceTime app. This app presents a list of your recent FaceTime calls (Figure 11-14, top left). Click the

button next to a name to place a video call. For an audio call, click

button next to a name to place a video call. For an audio call, click  next to the person’s name.

next to the person’s name.From Messages. If you’re chatting away with somebody by text and you realize that typing is no longer appropriate for the conversation, then click Details at the top of the screen. Click

(for a video call) or

(for a video call) or  and then FaceTime (for a FaceTime audio call).

and then FaceTime (for a FaceTime audio call).

Tip

If you right-click or two-finger click FaceTime’s Dock icon, you get a handy pop-up menu of Recent Calls. In other words, if you keep FaceTime in your Dock, you can place a new call to somebody on the spur of the moment, whatever you’re doing, without having to open FaceTime first.

At this point, the other guy receives an audio and video message inviting him to a chat. If he clicks Accept, then you’re on. You’re on each other’s screens, seeing and hearing each other in real time. (You appear on your own screen, too, in a little inset window. It’s spinach-in-your-teeth protection.)

Once the chat has begun, here’s some of the fun you can have:

Resize the window. Drag any window edge, or choose Window → Zoom.

Go Full Screen. Click the

button (or the green

button (or the green  button) (or the Full Screen button on your Touch Bar, if you have one [“The Complicated Story of the Function Keys”]) to make the window fill your entire screen. Click it again to restore the window.

button) (or the Full Screen button on your Touch Bar, if you have one [“The Complicated Story of the Function Keys”]) to make the window fill your entire screen. Click it again to restore the window.Move the inset. You can drag the little picture-in-picture window showing you to a different corner of the video window, if you like.

Rotate the screen. FaceTime works in either portrait (upright) or landscape (widescreen) view. Turn Video → Use Landscape on or off to choose, or click the curved arrow in the inset that shows your face. (If you’re calling someone using an iPhone or iPad, your Mac picture rotates automatically when your partner’s gadget rotates. You don’t have to turn the monitor 90 degrees.)

Mute the mike. Either choose Video → Mute, or click the

button at the bottom of the video window. The video continues. This is handy when you have to make throat-clearing sounds or yell at your kid in the background.

button at the bottom of the video window. The video continues. This is handy when you have to make throat-clearing sounds or yell at your kid in the background.Pause the call. You can also mute (black out) the video, for use when you have to perform small acts of personal grooming. To do that, click

.

.

Tip

The call is also paused whenever you minimize FaceTime.

When you and your buddy have had quite enough, click ![]() to terminate the call. And marvel that you were alive to see the day.

to terminate the call. And marvel that you were alive to see the day.

Group FaceTime

Well, it took eight years. But FaceTime, at last, can connect more than two people at once in a video chat. In fact, it can connect up to 32 people simultaneously, creating a video party line—as long as everyone concerned has macOS Mojave 10.14.1 or later, or iOS 12.1 or later on an iPhone or iPad.

Note

A Group FaceTime call is incompatible with pre-Mojave or pre-12.1 FaceTime calls. For example, if you have macOS High Sierra, you can’t place a FaceTime call to someone who’s already in a group call.

Begin the call

Often, you’ll want to dive into a group video call from within Messages, where a group chat is already underway. To do that, click Details at the top of the screen. Click ![]() . (Or, for a straight-up audio conference call, hit Audio.)

. (Or, for a straight-up audio conference call, hit Audio.)

Each participant gets a special Group FaceTime message, complete with a Join button. Once you click it, that special button in Messages changes to show how long the call has been going.

Tip

If you’re in a group Messages session, that Join button remains yours to click for as long as the group FaceTime call is still going. In other words, you don’t have to hop on instantly.

Or you can start in the FaceTime app. Click the + at top right; in the To box, specify the names of the participants. Then click Audio or Video. The other peoples’ phones start ringing, and when they click Accept, the audio or video conference begins!

During the call

In regular FaceTime calls, the other guy’s image fills the screen. How are you supposed to conduct a call with dozens of people?

Each face occupies its own rectangle; the more people who join, the smaller the rectangles get (Figure 11-15).

Figure 11-15. On a group FaceTime call, your icon always appears at lower right. The small icons at left, from left to right, mean: Hide/show call list; Mute microphone; Hang up; “Mute” camera; and Full screen.

When someone is talking, FaceTime brings that person’s rectangle front and center (and makes it bigger) automatically. In a lively conversation, therefore, the four main boxes seem to be constantly inflating and deflating to reflect who’s talking.

But even if someone’s not speaking, you can bring him to the front on demand, with either of two degrees of prominence:

Click his box once. It comes to the front, gets slightly larger, and reveals his name or iCloud ID.

Double-click his box. Now it gets much bigger, shamelessly covering up everyone else’s boxes. This is for when you really want to focus on this one person. (Click again to enshrink the box again.)

Tip

If you’ve clicked once, you can click the little ![]() icon to zoom that slightly enlarged box into the fully enlarged version.

icon to zoom that slightly enlarged box into the fully enlarged version.

The Roster

The FaceTime app can’t display big rectangles for more than four people at once. Starting with the fifth joiner, a horizontally scrolling row of faces joins yours at the bottom of the screen—Apple calls it the Roster. But the idea is the same: If one of them speaks, her box jumps into one of the larger four spots on the screen. And even if she’s not speaking, you can click or double-click her square to give it one of the two zoom treatments described already.

Coming and going

If someone’s inviting you to a group call, a notification lets you know. You’ll see an option called Join or ![]() , depending on what you’re doing on the Mac. Or, if you’re in Messages in a group chat, you’ll see a Join button.

, depending on what you’re doing on the Mac. Or, if you’re in Messages in a group chat, you’ll see a Join button.

If you’d like to add someone to a call that’s underway, click the screen, click ![]() , and click Add Person.

, and click Add Person.

If someone drops off the call (by clicking ![]() ), everyone else stays on the call, just as with a traditional conference phone call.

), everyone else stays on the call, just as with a traditional conference phone call.

FaceTime Audio Calls

Video calling is neat and all, but be honest: Don’t you find yourself making regular phone calls more often? Video calling forces us to be “on,” neatly dressed and well behaved, because we’re on camera. Most of the time, we’re perfectly happy (in fact, happier) with audio only.

To place an audio call, you start out exactly as you would when making a video call, as described earlier: in the FaceTime app, Contacts, or Messages. Click ![]() , and then click FaceTime Audio (as opposed to whatever phone numbers are listed there).

, and then click FaceTime Audio (as opposed to whatever phone numbers are listed there).

When you place an audio FaceTime call, the other person’s phone, tablet, or Mac rings. If she accepts your call, it’s better than being on a phone call in two ways. First, you don’t have the usual lag time that throws off your comic timing. And, second, the audio quality is amazing—more like FM radio than cellular. It sounds like the other person is right next to your head; you hear every breath, sniff, and sweater rustle.

Receiving Calls

Life is even simpler when somebody calls you. A notification bubble appears on your screen, and you hear an incoming-call sound. (Which ringtone? That’s up to you; in the FaceTime app, choose FaceTime → Preferences → Settings. Use the Ringtone pop-up menu.) If iTunes is playing music, it pauses automatically. Sweet.

If the Mac is asleep, it wakes; you can even answer the call on the Lock screen, without having to enter your password.

Click Accept to start the call, or Decline if now is not the time. (In that case, the caller will be told you’re not available.)

FaceTime doesn’t have to be running for you to receive a call. That’s generally a cool feature—but if you really don’t want to be interrupted, you can hang up a digital “Do Not Disturb” sign in any of these ways:

In FaceTime, choose FaceTime → Turn FaceTime Off.

Use the Do Not Disturb feature (“Insta-Respond to Bubbles”).

Sign out of FaceTime. (Choose FaceTime → Preferences → Settings, and then click Sign Out.)

Font Book

For details on this font-management program, see Chapter 14.

GarageBand

GarageBand, Apple’s do-it-yourself music construction kit, isn’t actually part of macOS. If you have a copy, that’s because it’s part of the iLife suite that comes on every new Mac (along with iMovie and Photos).

Home

HomeKit is Apple’s home-automation standard. The Home app lets you control any product whose box says “Works with HomeKit”—all those “smart” or “connected” door locks, security cameras, power outlets, thermostats, doorbells, lightbulbs, leak/freeze/temperature/humidity/air-quality sensors, and so on.

This app, new in macOS Mojave, is one of several that Apple has adapted from iOS to macOS. Among other limitations, this means you can’t actually set up any HomeKit gadgets in the Mac app. You still need an iPhone or iPad for that. The miracle of iCloud syncing brings the information onto the Mac (assuming that System Preferences → iCloud → Home is turned on).

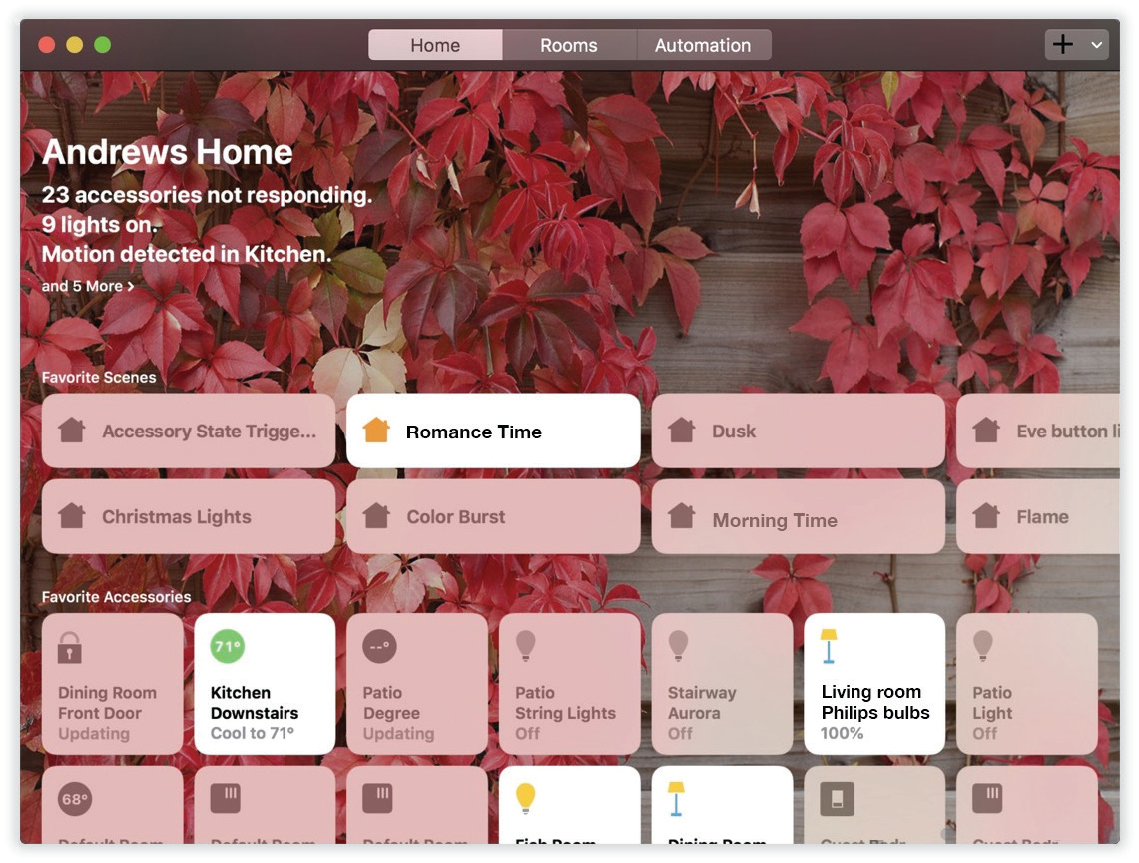

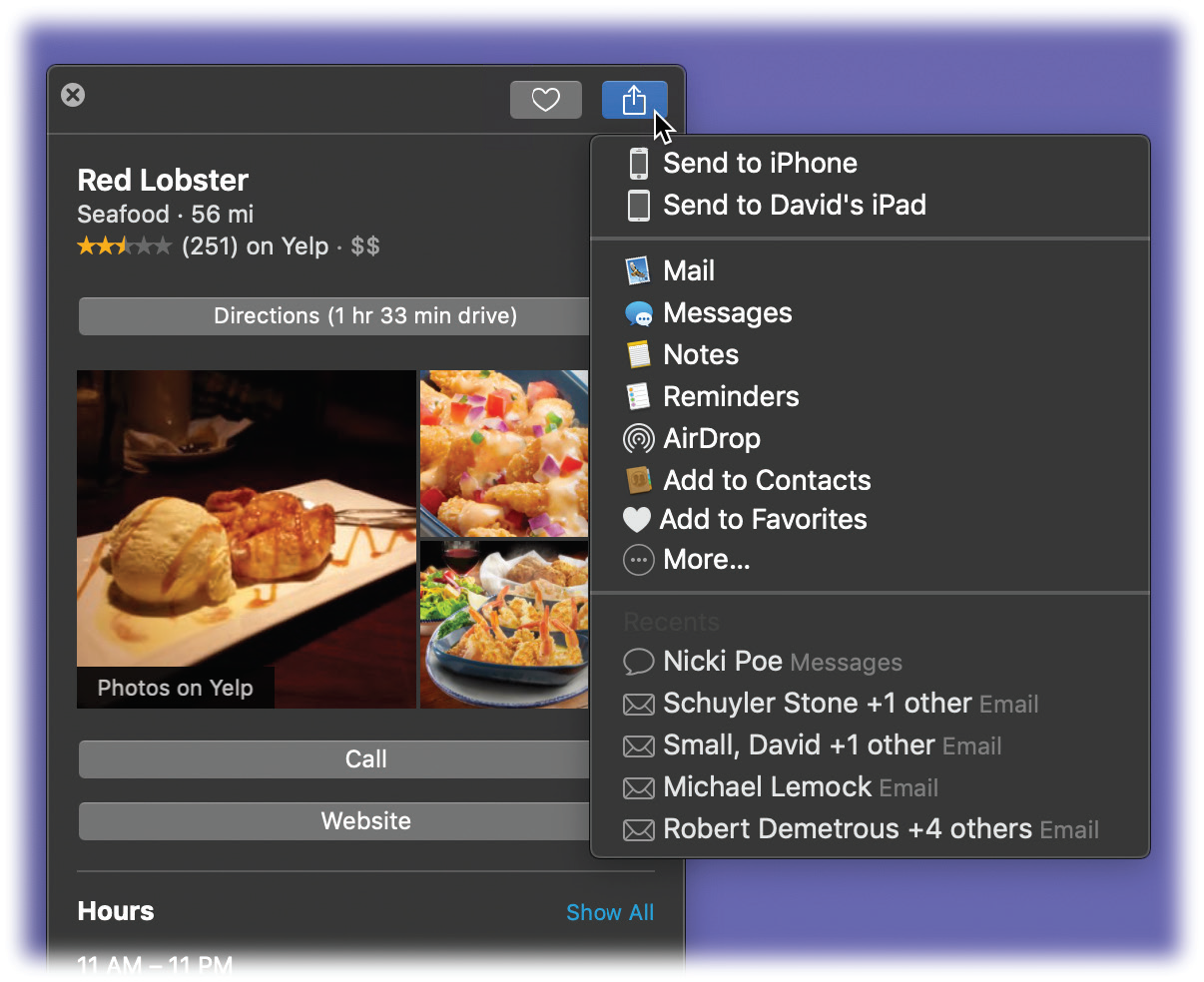

Once you’ve installed a gadget, you can use this app (Figure 11-16) to:

Turn it on and off by clicking its icon on the Favorites tab. Handy for light bulbs and locks.

Tip

You can do that either in the Home app or by using Siri voice commands (“Lock the front door,” “Turn on the downstairs lights,” and so on).