Throughout the last 13 chapters, you’ve assembled all the pieces for a first rate database. But without a good way to bring them all together, they’re just that—a pile of unorganized pieces.

The best Access databases include some way for people to jump from one part of the database to another. The goal’s to make the database more convenient and easier to use. Rather than forcing you to hunt through the navigation pane for the right object, these databases start with some sort of menu form, and let you work your way from one task to another by clicking handy buttons. This sort of design’s particularly great for people who aren’t familiar with Access’s kinks and quirks. If the navigation system’s built right, these people don’t need to know a lick about Access—they can start entering data without learning anything new.

You already know most of what you need to create a first-rate navigation system. Now you need a new perspective on databases—namely, that they can (and should) behave more like ordinary Windows programs, and less like intimidating forts of data. In this chapter, you’ll learn different ways to add user-friendly navigation tools to a database. You’ll learn how to create switchboards (forms that direct people to other forms), how to make a form appear when you first start the database, and how to show related information in separate forms. But first, you’ll start by taking a closer look at the navigation pane to learn how you can control navigation without creating anything new.

Chapter 1 introduced the navigation pane, and you’ve used it ever since to breeze around the database. However, the navigation pane starts to get congested as your database grows. Depending on your monitor size, once you hit about 20 database objects, they don’t fit into view all at once. As a result, you need to scroll from top to bottom to find what you need, which can be a major pain in the wrist.

One way you can combat this confusion is by designing your own switchboard forms that let you move around the database. But before you jump to that solution, it’s worth considering some of the features built right into the navigation pane. These features may solve the problem with less work.

For starters, consider using filtering to cut down the amount of information shown in the navigation pane. You might have a database with three dozen objects, only 10 of which you use regularly. In this case, there’s no reason to show the objects you don’t use.

Essentially, Access lets you make two decisions with the navigation pane:

You can choose the way objects are arranged in the navigation pane. This process is known as categorizing your database objects.

You can choose which objects are hidden from view. This process is known as filtering your database objects.

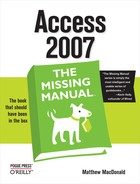

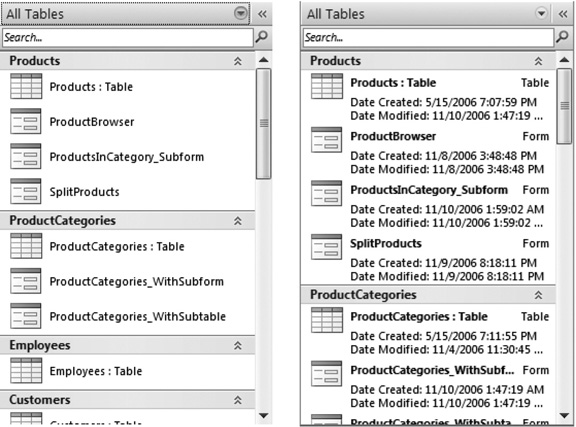

The confusing part’s that you make both these choices using the same menu. To open this menu, click the drop-down arrow in the navigation pane’s title region. Figure 14-1 explains how it works.

You can choose to categorize the navigation pane in five ways:

Tables and Related Views groups database objects based on the table they use. If you’ve created two forms, three queries, and a report for a Students table, you’ll see all these objects together in one group (under the heading “Students”). The challenge with this option’s that you can have a hard time telling the difference between the different types of database objects, particularly if you use similar names. You need to look carefully at the icon to determine whether a given item’s a form, a report, or something else. Tables and Related Views is the categorization setting with which Access starts you off.

Tip

Many database objects use more than one table. If you create a query that uses a join (Section 6.3) to show products with category information, then your query uses both the Products and ProductCategories tables. In Tables and Related Views mode, you see this query in two places—under the Products heading and under the ProductCategories heading.

When you use Tables and Related Views, the menu’s Filter By Group section includes every table in your database. If you choose a specific table, then you see only the objects that are related to that table. You can also choose Unrelated Objects to see any objects that don’t fit into one of the table-specific categories, like code files.

Figure 14-1. When you’re ready to tell Access how to arrange objects in the navigation pane, make your selection in the menu’s top portion (named Navigate to Category). The current choice—Object Type—groups tables, queries, forms, and reports into separate sections. To decide which objects appear, make a selection in the menu’s bottom portion (named Filter By Group). These options let you decide how your database objects are grouped These options let you control which objects appear

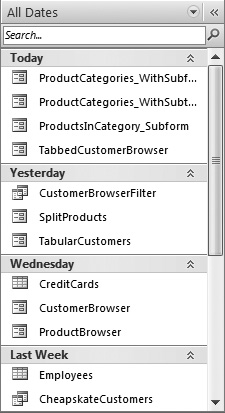

Object Type groups database objects based on the type of object. This method clearly distinguishes tables from forms, reports, and other sorts of objects. Many Access gurus prefer using this view when browsing a complete database, because it imposes order on the unruliest database. It also works particularly well if you don’t remember the exact name of the object you want. If you know you need to print a report that shows a list of classes, then you can head straight to the Reports group.

When you use Object Type, the filtering list lets you see just a single type of object. If you’ve created forms for every task you need, then select Forms to see your forms and hide everything else.

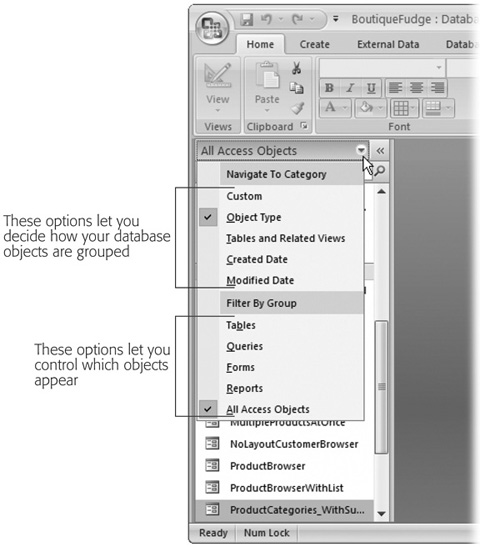

Created Date groups database objects based on the time they were created. Access creates a group for Today, groups for the recent days of the week (Monday, Sunday, and so on), and groups for longer intervals (Last Week, Two Weeks Ago, and so on). You probably won’t use this view mode regularly, because as time passes, the objects move from one group to another. However, it’s a good way to hunt down recent work.

When you use Created Date, the filtering options let you pick out just those object that were created today, yesterday, last week, last month, and so on (as shown in Figure 14-2). If you remember when you created an important form or report, but don’t know its name, this ability can save serious time.

Modified Date works like the Created Date option, except it lets you pick out database objects that have been changed recently. This option’s handy if you want to ignore tables and other objects that you rarely use.

When you use Modified Date, you get all the same filtering options you do with Created Date.

Custom lets you choose exactly what database objects are shown, and which ones are hidden. This choice is good if you have certain commonly used objects, and others that you want to tuck out of sight. You’ll try out custom groups in Section 14.1.4.

Tip

You can quickly apply filtering. Right-click a group heading, and then choose Show Only [Group-Name]. To show just tables when grouping by Object Type, right-click the Tables group, and then choose Show Only Tables. To remove the filtering, right-click the navigation pane again, and then choose Show All Groups.

When you apply filtering in the navigation pane, Access completely hides whatever you don’t want to see. But as you probably already know, Access gives you another option. You can click the collapse arrows next to a specific section to shrink it down so that only the section title’s visible (Figure 14-3). You can then pop it back into display when you need it.

The filtering system has one limitation—it lets you choose only one category at a time. If you’ve chosen Tables and Related Views, then you can filter the list down to the objects that are related to a single table. However, you can’t choose to include two (or more) table groups. Similarly, if you choose Object Type, then you can show all the forms or all the reports in your database, but you can’t show forms and reports without including everything else (although the collapsing trick shown in Figure 14-3 helps to reclaim most of the space).

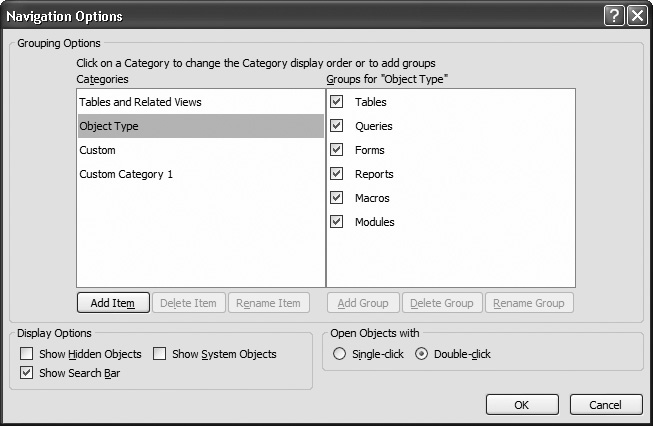

There’s an easy way around this restriction. To get more control over filtering, follow these steps:

Right-click the navigation pane’s title bar, and then choose Navigation Options.

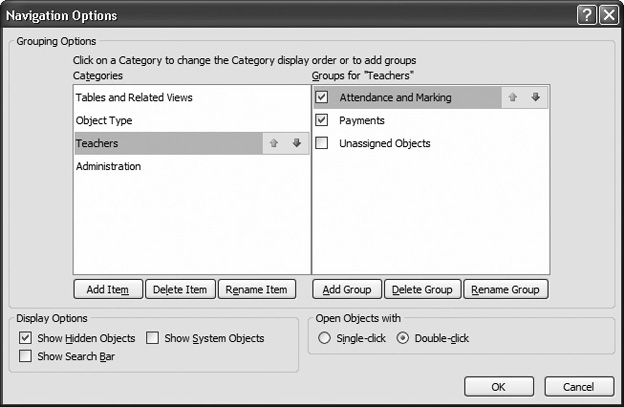

The Navigation Options dialog box appears (Figure 14-5).

Choose the category you want to customize—either Tables and Related View or Object Types.

The list on the right shows all the groups in that category.

If you don’t want a category to appear in the navigation list, then clear the checkmark next to it.

If you want your navigation pane to show only reports and forms, choose the Object Types category, and then clear the checkmark next to Tables, Queries, Macros, and Modules.

If you’re customizing the Tables and Related Views category, then you can also change the order of the groups, as shown in Figure 14-6 .

The only item you can’t move is Unrelated Objects, which always appears at the bottom. And you can’t change the order of the groups in the Objects Types category at all.

Click OK to close the window.

Hiding the groups you don’t want to see is all well and good—but what if there’s a single object you want to tuck out of sight? Maybe you want to make sure other people who use your database aren’t distracted by a few potentially risky action queries (Chapter 8) that they really shouldn’t use. No problem. Just right-click the query in the navigation pane, and then choose Hide in this Group.

Note

When you hide an object, it’s hidden in the current view mode, in the current group. (Remember, in Tables and Related Views mode, some objects may appear in more than one group.) If you want to hide an object everywhere, you need to track it down in each group, and hide it there.

To reveal a hidden object, you first need to configure the navigation pane so that it shows hidden objects. To do so, right-click the title bar, choose Navigation Options, add a checkmark in the Show Hidden Objects box, and then click OK. Now, hidden objects appear in the navigation pane, but they’re slightly faded so you can distinguish them from the other non-hidden objects. To unhide an object, right-click it, and then choose Unhide in this Group.

All of these approaches—filtering, custom groups, hidden objects—are designed to make your database easier to use. These approaches don’t provide any security. (A person who really wants to use a database object can just change the navigation settings to get to it.)

Note

in Section 18.2, you’ll learn how to divide a database into separate files, which gives you the best way to keep some database objects out of the wrong hands. However, no matter what you do, Access is not bulletproof. Access is designed to be intuitive, capable, and easy to use. Unlike server-side databases like SQL Server (Section 20.1.1), it’s not designed to lock out bad guys if they get hold of your database files.

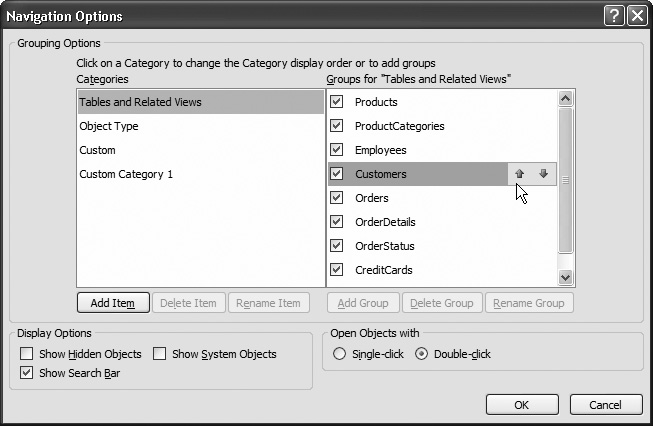

Ordinary people don’t think in terms of tables and database objects. Instead, they think about the tasks they need to accomplish. But none of the ready-made grouping options fit this approach. Fortunately, you can build your own groups that do. Here’s how:

Click the drop-down arrow in the navigation pane’s title bar, and then choose Custom.

In a new database, you start out with two groups in the Custom view. The first, Custom Group 1, is empty. The second, Unassigned Objects, contains all the objects in your database.

You can create a new group and move an object into it in one step. To do so, right-click the object you want to relocate (in the Unassigned objects section), and then choose Add To Group → New Group. Enter the group name, and then hit Enter. Figure 14-7 shows the results.

Repeat this step to create all the groups you need. If you want to move an object into an existing group, right-click it, choose Add To Group, and then pick the corresponding group name.

You can also rename, remove, and reorder your groups. The easiest way to do this is using the Navigation Options dialog box. Right-click the navigation pane’s title, and then choose Navigation Options.

The Navigation Options dialog box lets you make a few useful group-related things happen:

Figure 14-7. It’s often a good idea to create groups that reflect specific types of tasks, as in this database.

Select a group, and then click Rename Group to apply a new name.

Remove your group—just select it, and then click Delete Group.

Add a group, by clicking Add Group. It starts with no objects.

Rearrange your groups. Just click one, and then use the arrow icons that appear to move it up or down.

Move your custom category to a different place in the list, which affects how the menu appears when you click the drop-down arrow in the navigation pane.

Hide a group (temporarily, or for the long term). Just remove the checkmark next to the group.

The only thing you can’t do with groups in the Navigation Options dialog box is change the objects that each group contains. (In order to change them, you need to drag your objects around the navigation pane, as described in step 2.

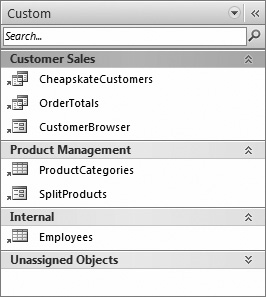

You can also change the name of the view that contains all your groups. Initially, this category’s named Custom, but you can change it to something more descriptive by selecting it in the Navigation Options dialog box, and then clicking the Rename Item button. And if you’re more ambitious, you can create more than one top-level custom view mode. Click Add Item to add a new one, and Delete Item to remove it. Figure 14-8 shows an example with several custom categories.

Click OK when you’re finished making your changes.

If you just can’t bear to have anything out of your sight, you may need to put up with a cumbersomely long list of objects in the navigation pane. However, Access still provides you with one convenient feature that can save you hours of scrolling.

Figure 14-8. One reason you might create multiple views is if different people use your database. In the Cacophoné Studios example, the administrative staff sees forms for creating classes and adding students (using the Administration view), while the teachers get to print attendance lists and create assignments (using the Teachers view, which is selected here). As you can see, the Teachers view contains a category named “Attendance and Marking” and one named “Payments”. Each has its own set of forms and reports.

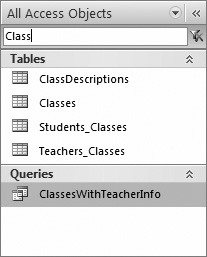

It’s the search box, and it lets you jump to an object almost instantaneously, pro-vided you know its name.

To show the search box, follow these steps:

The search box appears at the top of the list in the navigation pane. As you type, Access filters down the list so it includes only matching objects (Figure 14-9).

The navigation pane’s an invaluable tool for getting around your database, but it doesn’t suit everyone. People who’ve never used Access before might find it a little perplexing, and there’s nothing stopping someone from changing the navigation options (and opening objects they shouldn’t).

To get more control and add a friendly veneer, many Access experts build navigation features into their forms (and occasionally their reports). After all, a form gives you virtually unlimited possibilities for customization. You can add a paragraph of text, throw in a hot pink background and a company logo, and reduce confusing options to a few fat, friendly buttons.

If you do decide to use forms for navigation, your first decision’s what kind of form to build. Access gives you a few options, including built-in support for something it calls switchboards.

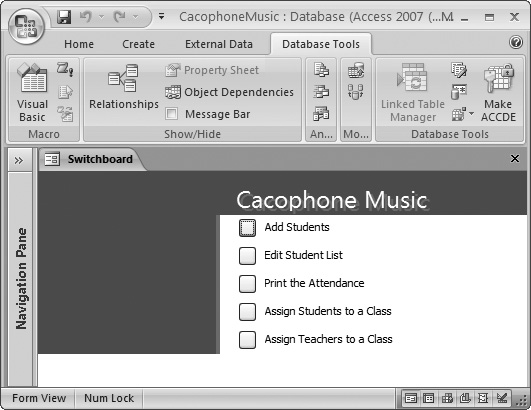

A switchboard is a form whose sole purpose is to lead you to other forms (usually, when you click a button). Think of a switchboard as the main menu for your database. It’s both the starting place and the central hub of activity. A typical switchboard form has a stack of buttons that lead to different places.

Figure 14-10. This Access switchboard provides single-click access to five different forms. The nice thing about Access switchboards is that you can click your way to building one in a matter of seconds. The drawback’s that they have a slightly dated look, which leads picky people to design their own from scratch.

Note

A switchboard, once created, is like any other type of form. So you can use the skills you picked up over the last two chapters to give your switchboard a personal touch after you create it.

To automatically create a switchboard, you need to use the Form wizard. Here’s how it works:

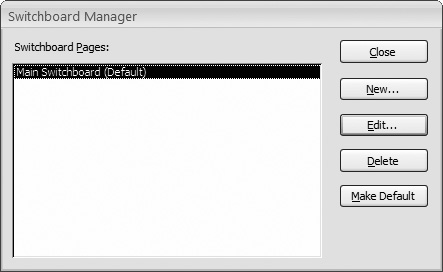

Choose Database Tools → Database Tools → Switchboard Manager.

The first time you click this button in a database, Access informs you that it can’t find a switchboard, and asks if you’d like to create one. Click Yes to continue to the Switchboard Manager (Figure 14-11).

If a switchboard already exists, then you’ll barrel ahead to step 2, where you can edit the current switchboard.

Click Edit to edit the main switchboard page.

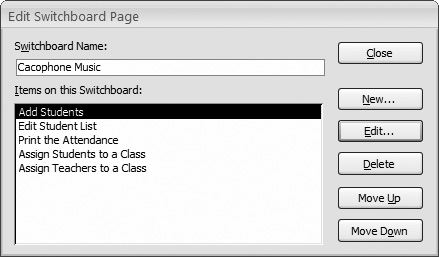

The Edit Switchboard Page window appears (Figure 14-12). Here’s the spot where you’ll define the actual menu commands.

To create a new menu command, click New.

The Edit Switchboard Item window appears (Figure 14-13). To create a menu command, you need to supply two pieces of information: the text that appears on the form, and the command that Access should perform when you click the button.

Enter the menu text, and then choose the action you want the button to perform.

Your options include:

Go to Switchboard jumps to another switchboard page. You can use switchboard pages to break up really large menus into several smaller menus.

Open Form in Add Mode opens a form in data entry mode so you can start adding new records.

Open Form in Edit Mode opens a form in its normal mode for viewing or editing records. (This mode doesn’t let you edit the form, contrary to the misleading name.)

Open Report launches a report in print preview mode.

Design Application opens the Switchboard Manager window so you can edit the switchboard menu. You rarely need to include this option in the menu.

Exit Application quits Access.

Run Macro and Run Code fire up a macro you’ve created (see Chapter 15) or a piece of Visual Basic code you’ve written (Chapter 16).

Repeat step 3 and 4 until you’ve created all the commands you need. Then click Close to move back to the main Switchboard Manager window.

Switchboards have an ugly secret: Each page can accommodate only eight menu commands. If you need more (and who doesn’t?), you need to add extra pages to your menu, as described in the next step.

If you’ve decided to use more than one switchboard page, click New to add the page, enter the page name, and then click OK. Next, click Edit to start adding commands, and then Close when you’re finished.

Follow the instructions in steps 3 to 5 to fill in the commands for this page.

When your switchboard’s complete, click Close in the Switchboard Manager window.

To try out your switchboard, find the new Switchboard form that Access has created, and then double-click it.

Switchboard forms don’t always look right with the tabbed windows that Access uses. Mainly, there’ll be some extra blank space at the bottom and the right side.

To remedy this problem, you can show the switchboard form as a pop-up window that appears above all other windows. That way, the window’s always sized correctly. To make this change, open your form in Design view. Using the Property Sheet to configure the form, choose the Other tab, and then set the Pop Up property to Yes.

Seeing as the switchboard’s the gateway to your Access database, it’s a good starting point for folks who are going to use your database. You can tell Access to open any form (like the switchboard) automatically when someone first opens your database. Here’s how:

Choose Office button → Access Options.

The Access Options window appears.

In the list on the left, click Current Database.

The settings for the current database appear.

Under the Application Options heading, look for the Display Form box. Choose your switchboard form in the list.

Now, whenever you open the database, Access launches your form immediately.

Optionally, if your switchboard completely eliminates the need for the navigation pane, look down under the Navigation heading and clear the checkbox next to the Display Navigation Pane setting.

If you’re worried about overzealous folks opening something they shouldn’t, then hide the navigation pane, and train them to use the switchboard for all their needs. It’s like navigating the database with training wheels on.

Tip

Every time you finish a task in a database, you return to the switchboard and pick another task (or just exit Access). To make this process easier, you may want to add a button to each form you create that closes it, allowing the switchboard to come back to the forefront. You can do this using the Command Button wizard (Section 13.2.7).

Switchboards are a great idea, but they have some clear drawbacks. The eight-item limit, the slightly antiquated look, and the extra maintenance are all good reasons to think twice about using a switchboard unless it’s clearly simplifying the navigation in an otherwise complicated database.

If you aren’t quite convinced that the Access switchboard fits the bill, you have some other options, as described in the following sections.

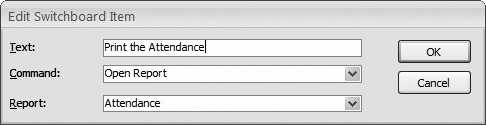

One of the simplest and most compelling approaches is to build your own switchboard form by hand, and then set that as the startup form for your database. Consider the form shown in Figure 14-14, which presents the same navigation buttons as the switchboard in Figure 14-10, but adds a hefty dose of modern styling. This switchboard presents a clean blank surface along with an image control that shows a snazzy graphic. It also includes several ordinary button controls that were created with the Command Button wizard (Section 13.2.7). Each button’s Back Style property’s set to Transparent, to give it a more modern flat look. The Cursor On Hover property’s set to “Hyperlink hand” so that the mouse pointer changes to a pointing hand when you move over a button, which lets you know that you can click there.

Note

Another approach is to use a picture as the background for the whole form, and put other controls on top. To do this, you need to set these properties on the form: Picture (the picture file you want to show), Picture Tiling (whether or not the image should be repeated to fill the available space), Picture Alignment (use Top Left so that it starts from the form’s top-left corner), and Picture Size Mode (use Clip, so the picture’s not stretched, resized, or otherwise mangled). All the controls you place on top of a form with a background picture should have their Back Style property set to Transparent so that the picture shows through.

Check out the “Missing CD” page at http://www.missingmanuals.com to see a screencast (an online, animated tutorial) that demonstrates how the custom switchboard shown in Figure 14-14 was created.

Figure 14-14. This custom switchboard’s just an ordinary form with a lot of navigation buttons. The advantage to crafting your own switchboard is that you can make everything just the way you like it. The disadvantage is that it’s more work to update when the database changes. Every time you add a new form, you need to modify your switchboard’s design to use it.

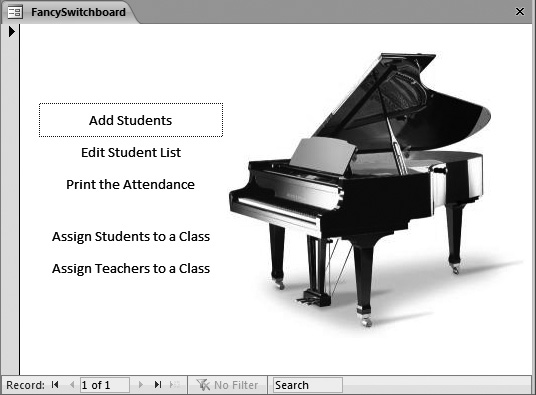

Alternatively, you could forget about designing a way to jump from form to form, and instead create a form that brings everything you need into one place. This trick, called a compound form, uses the subform control you learned about in Section 13.3.1.

In Chapter 13, you learned how the subform control lets you show related data (like a list of products for the current product category). However, the subform also makes sense if you want to show several unrelated tables in one place. Just leave the Link Master Fields and Link Child Fields properties of the subform empty—that way the subform shows all the records without filtering. Figure 14-15 shows an example.

Tip

There’s a shortcut to creating a compound form. First, choose Create → Forms → Form Design to create a blank new form. Find a form you want to use in the subform, and then drag it from the navigation pane to your new form’s design surface. Access creates a subform control that shows that form. You can also drag a table onto your form, in which case Access creates a subform for that table (and asks you to pick a name for it).

Figure 14-15. This compound form’s an all-in-one dashboard for adding and reviewing products and reviewing the customer list. The prebuilt templates that Access includes (Section 1.2.1) often use compound forms to put several related editing tasks in one place.

If you’re using Tables and Related Views mode in the navigation pane, a compound form usually appears in the Unrelated Objects area. That’s because the switchboard form itself doesn’t use any tables. Instead, it contains subforms, and these subforms use the various tables you’re displaying.

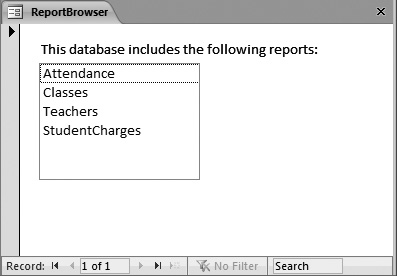

You may find one last trick useful when building a navigation hub. Rather than create a button for each and every form you want to use, you can create a list control that has them all. When the person using the database picks a form from the list, Access jumps to that form. This approach works well if you have a large number of forms, which would make the button-only approach irredeemably cluttered.

The first step’s to put the form names in a list box. Access gives you three ways to do this:

Type the names in by hand. Just drop a combo box control onto your form. When the wizard starts, choose “I will type in the values that I want”, and then enter the form names in the appropriate order.

Note

Section 13.2.6 has more about the List wizard. Just remember, at the end of the wizard, you need to choose “Remember the value for later use”. Your list’s used for navigation, not record editing.

Pull the names out of a custom table you create. Create a new table, and then fill it with the names of the forms you want to show in the list. Then, when you create the combo box, choose “I want to look up the values in a table or query”, and then specify your custom table. This method’s conceptually similar to the way that an Access-generated switchboard works.

Pull the names out of the system table. For a really nifty trick, you can get the full list of forms straight from your database without any extra work. The trick’s to use one of the hidden system tables. These system tables are tables that Access uses to keep track of database objects. Every Access database has these tables, but tucked out of sight.

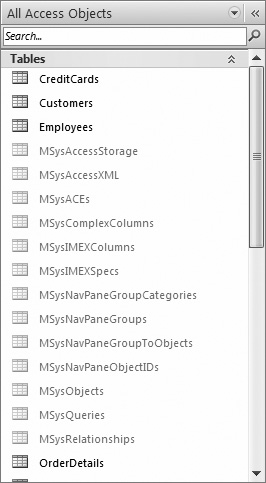

The first two options are straightforward. The third option’s more impressive, but it takes a little more work. Ordinarily, the system tables are hidden from sight. You can pop them into view (see Figure 14-16) by choosing Show System Objects from the Navigation Options window. Showing the system tables isn’t a good choice for the long term, because any change you make in these tables could damage your database and confuse Access.

Even if you don’t show the system tables, you can still use them. The most interesting system table’s MSysObjects, which lists all the objects in your database. You can get a list of all the forms in your database by querying this table with an SQL command (see Section 6.2.3 for a refresher on how queries use SQL). The Name field provides the database objects’ name. The Type field contains a numeric code that identifies the type of object. Table 14-1 lists the types in which you may be interested.

Figure 14-16. Here, the navigation pane shows a bunch of system tables, which are ordinarily hidden. You can open them to take a look, but you’ll have a hard time making sense of the (mostly numeric) data they contain.

Based on this information, you can get a list of forms by retrieving the Name field, and then filtering out those records with a Type value of -32768.

You can most easily build this bit of logic into your list control by adding your list to the form and skipping out of the wizard (hit Esc when it starts). Then, you can configure the control using the Property Sheet. In the Data tab, find the Row Source property, and then enter the following SQL statement, which performs the query you need:

SELECT Name FROM MSysObjects WHERE MSysObjects.Type=-32768

You now have a list that shows all the forms in the database. You can substitute the number -32764 for -32768 to get reports instead; Figure 14-17 shows the results.

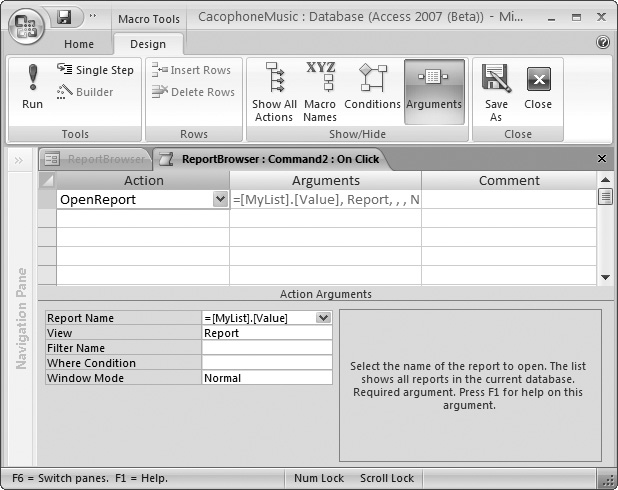

So far, you’ve seen only half of the solution you need. You’ve learned how to get the list into the right control, but at the moment nothing happens when you use the control. You really need a way to jump to the selected form or report.

It turns out that this solution’s a bit more advanced than the examples you’ve seen so far. In order to make it work, you need to customize a macro. (A macro’s a list of one or more instructions that’s stored as a database object so you can use any time.)

As you learned in Chapter 13, when you create a command button, the Button wizard asks you a few questions, and then builds the macro you need. However, the Button wizard’s woefully underpowered. For instance, while it can create a macro that navigates to a specific form, it can’t create a macro that can go to any form. But with just a little more work, you can create a simple macro with the wizard, and then fix it up to really suit your needs. Here’s how:

Drop the button onto your form.

Place it next to the combo box control. The Button wizard launches.

Choose the Report Operations category and the Open Report action, and then click Next.

Or, if you’re showing a list of forms, choose the Format Operations category and the Open Form action.

Pick any report (or form), and then click Next.

It doesn’t matter what you choose here, because you’ll change this part later.

Complete the wizard.

Make sure you give your button a suitable caption, like “Go,” “Open Form,” or “Show Report.”

Once the wizard’s finished, it’s time to take a closer look at the button in the Property Sheet.

In the Property Sheet, select your newly created button, and then switch to the Event tab.

Events are occurrences that can trigger your macros. For example, every button has an OnClick event that takes place when you click the button.

Find the OnClick property, and then click inside the property box, where it says [Embedded Macro].

An ellipsis (…) appears at the corner of the box.

Click the ellipsis to edit the macro.

A macro editing window appears (Figure 14-18). In the lower portion of the window, an Action Arguments section lets you edit how the macro works.

Figure 14-18. You’ll learn much more about this window in Chapter 15. For now, all you need to know is that this macro has a single action (represented by the single line in the grid). That action opens a report (as indicated by the OpenReport value in the Action column). The Arguments column has all the additional information—namely, which report to open.

In the Action Arguments section, find the Report Name (or Form Name) property. Change it to the expression =MyList.Value

This expression finds your combo box, and pulls out the currently selected value. It assumes your combo box is named MyList. If not, change the expression accordingly. (If you don’t remember the name of your list control, click to select it, and then look at what name appears in the drop-down list at the top of the Property Sheet.)

Close the macro window, and then choose Yes to save your changes when prompted.

You return to the form design window.

Switch to Form view, and then try out your new list mojo.

You should be able to select a form in the list, and then click the button to open the form you chose.

The switchboard’s the secret to providing a bird’s-eye view of your database. However, your work doesn’t end here. A well-designed navigation system lets you move easily from one form to the next, so you can move efficiently through your entire database.

The secret to form-to-form navigation is thinking about your workflow (that is, the order in which you move between tasks when working on your database). Suppose you’re a furniture company selling hand-painted coffee tables. What happens when you receive a new order? Probably, you start by creating or selecting the customer (in one form), and then you add the order information for that customer (in another form). The switchboard doesn’t need to go directly to the order form. Instead, you should start with a customer form. That form should provide a button (or some other control) that lets you move on to the order form.

You need to go through a similar thought process to create forms for, say, the customer service department. In their case, they need a way to pick a customer and see, at a glance, the billing and payment details, the order information, and the shipping records. The best solution in this scenario could be to create a compound form that pulls everything together.

Getting from one form to another is easy. All you need’s the right button. The following two sections walk you through two common examples.

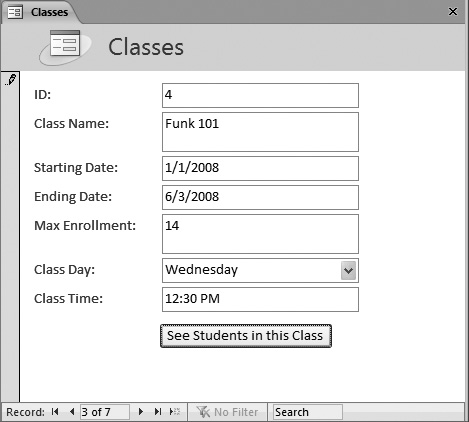

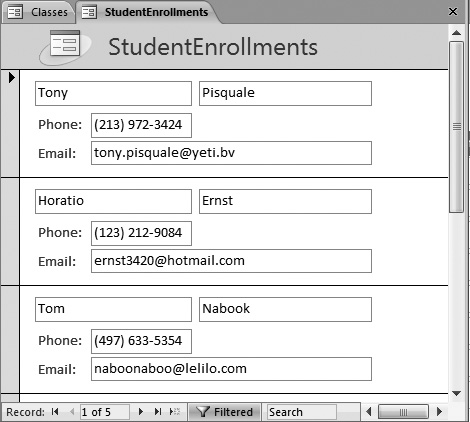

In Chapter 13, you learned how a subform control can show linked records in one place (Section 13.3.1). However, subforms don’t always give you enough room to work. Depending on the way you work and the sheer volume of information you’re facing, you may prefer to show the related records in a different place. You could add a button to your form that pops open another form with the linked records. The trick to making this work is using filtering in the second form so that it shows only the related records. Figures 14-19 and 14-20 show an example with the Cacophoné Studios database.

You can create the two forms that appear in Figures 14-19 and 14-20 without much effort. The tricky bit’s creating the “See Students in this Class” button.

Here’s what you need to do to wire up a button that opens another form to show related records:

Open the parent form.

Here, you start with the Classes form.

In the Design tab, click the Button icon. Draw the button onto your form.

The Button wizard springs into action.

Figure 14-19. The Classes form shows a list of classes. Click “See Students in this Class” to open a second form (Figure 14-20).

Choose the Form Operations category, choose Open Form, and then click Next.

The next step in the wizard shows all the forms in your database.

Choose the child form that has the related records, and then click Next.

In this case, choose the StudentEnrollments form.

Choose “Open the form and show all the records”, and then click Next.

This part seems a bit odd—after all, don’t you want to show just the related records in the StudentEnrollments table? Of course you do. But unfortunately, the Button wizard can’t help you—it has a nasty bug in this area that prevents it from creating the right filter condition. So you need to do a bit more work to define the filter condition yourself.

Enter some text, and then choose a picture.

From this point on, the Button wizard shows the standard steps you learned about earlier (Section 13.2.7).

Supply a name for the button, and then click Finish.

Now you have a button that opens the form you want, but doesn’t filter it down. To add that part, you need to change the macro that the button uses.

If the Property Sheet isn’t visible, then choose Form Design Tools | Design → Tools → Property Sheet.

Select your button by clicking it on the design surface.

Or, you can choose it from the list at the top of the Property Sheet.

In the Property Sheet, choose the Event tab, and then click the On Click box.

You see the text [Embedded Macro] there, which indicates that there’s a macro attached to this event.

Click the ellipsis button to open your macro for editing.

A new tab appears, which lists all the actions your macro performs, in order. You’ll learn your way around this window in Chapter 15. For now, you have just two simple changes to make.

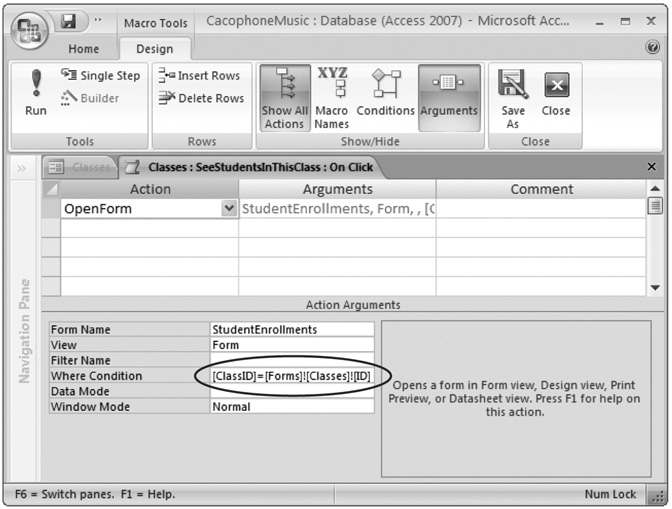

At the top of the list, you see an action named OpenForm. (This action opens your child form when the button’s clicked.) Click to select it (Figure 14-21).

When you select an action in a macro, a bunch of information about it appears in the Action Arguments section at the bottom of the window.

Click the Where Condition box (in the Action Arguments section at the bottom of the window), and then type in your filter expression.

This filter expression needs to select the linked records. In the current example, that means you’re interested in records that have the current class ID. Here’s the expression you need:

[ClassID]=[Forms]![Classes]![ID]

This expression tells Access to show an enrollment record only if the ClassID value in the StudentEnrollments form matches the ID value in the Classes form. In other words, you’re getting the student enrollments for the current class.

Note

The strange exclamations in this filter expression let you link two forms. The filter expression’s being set on the form you’re opening (the StudentEnrollments form), which has the ClassID field. However, you need to narrow down the records it shows based on the ID field in another form (Classes). The syntax [Forms]![Classes]![ID] is just a fancy way to tell Access to go looking for the ID value it needs on a currently open form named Classes.

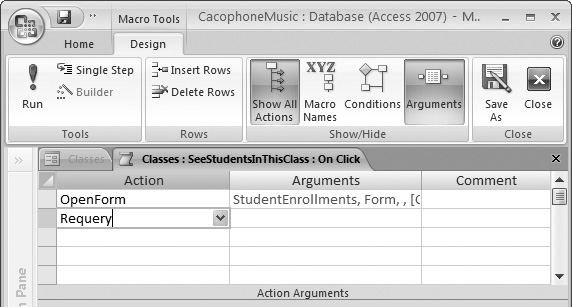

The change you made in the previous step almost completes your macro. However, it’s a good idea to add one more action. Click the box underneath OpenForm, and then type Requery (Figure 14-22).

This instruction tells Access to refresh the current form (which is the StudentEnrollments form you just opened). This step’s necessary because the StudentEnrollments form might already be open when you click the “See Students in this Class” button. If it is, your macro changes its filter, but the filter doesn’t spring into action. To update the record display, you need to use Requery to force the form to refresh itself.

Now you’re finished. Close the macro tab, and then click Yes when Access prompts you to save it.

Now you have a perfect navigation button that shows a related form and cuts it down to just those records that you’re interested in. You’ll learn much more about fine-tuning macros in the next chapter.

To try out your button, switch to Form view, and then give it a click. When you click the “See Students in this Class” button and the StudentEnrollments form appears, your filtering takes effect.

Tip

There’s nothing to stop someone from removing your filtering using the ribbon’s Home → Sort & Filter section (or by clicking the Filtered button that appears at the bottom of the form, next to the navigation buttons). If you don’t want to allow this flexibility, you can configure the StudentEnrollments form so it doesn’t let anyone change its filtering settings. To do so, open the form in Design view, select the Form item in the Property Sheet list, and then change the Allow Filters property from Yes to No.

You can use a similar technique to allow navigation in reports. If you want, you can create a way to jump from one report to another, related report. In fact, the macro you need to create’s almost identical to the one in the previous example.

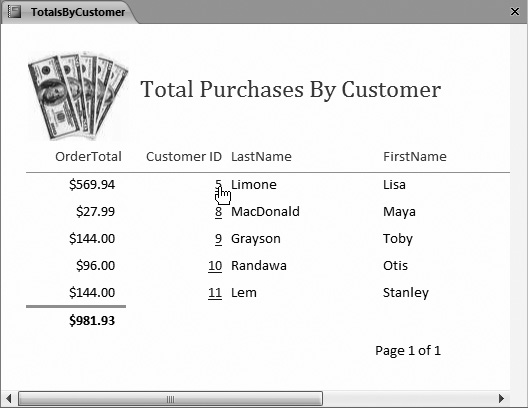

Usually, Access experts use this technique to start with a general report, and let people click their way to a more detailed report that highlights part of the data. Figures 14-23 and 14-24 show an example.

Note

Reports are designed to be printed. For that reason, big gray buttons look a little out of place. Your other option—linking—as shown in this example, is much more common because it shows the data you need to print, and adds interactivity at the same time.

To create this navigation, you need to begin by creating a text box that looks like a hyperlink. (You can’t use the bona fide hyperlink control, because it displays only fixed, unchanging text. Instead, you need a way to display a field’s content as a link—in this example, the customer ID.) You can then create a macro that springs into action when the text field’s clicked, to move you to the new report. This macro’s job is to open the detailed report that you want, and then apply filtering so that only the related records appear.

Figure 14-23. The first report (TotalsByCustomer) shows all the customers and their total orders. Click a single customer, and then Access launches the more detailed report shown in Figure 14-24.

Figure 14-24. Here’s the CustomerPurchases report that profiles the selected individual’s spending habits. A string-building expression (="Products Purchased By " & [FirstName] & " " & [LastName]) puts the current customer’s name into the title.

You can easily format the text box. You can select any control, and then change its color, font, and so on, using the commands in the ribbon. However, you don’t even need to perform this work. That’s because every text box has an odd property named Is Hyperlink—set this to Yes, and the text box morphs into a blue underlined piece of text, which is just what you want.

Once that’s out of the way, it’s time to add the macro you need. You can use the following steps with the Boutique Fudge database (included with the downloadable content for this chapter) to add a link that opens the CustomerPurchases report to the TotalsByCustomer report.

Open the report you want to use in Design view.

In this example, everything starts at the TotalsByCustomer form.

If the Property Sheet isn’t visible, then choose Report Design Tools | Design → Tools → Property Sheet.

Decide what field you want to use to create the link, and then select it.

Usually, you’ll want to use the unique ID value that links two tables together. Here, you use the ID field that stores the customer ID. If you haven’t already, you should format this field to look like a link using the Is Hyperlink property.

Now it’s time to create and attach your macro.

In the Property Sheet, switch to the Event tab, and then click the On Click box. Click the ellipsis (…) button.

The Choose Builder dialog box appears, and asks you how you want to create the code that runs when the link’s clicked.

Choose Macro Builder, and then click OK.

The macro editing window appears.

In the first row, in the Action column, click the drop-down arrow. Choose OpenReport.

You could also use OpenForm to launch a form (for editing) when the report link’s clicked.

In the Action Arguments section, change the Report Name property to the report you want to use.

In this example, that’s CustomerPurchases.

Now you need to set the Where Condition property to apply your filter. Your filter needs to select customers that match the ID value in the current record.

The expression you need’s very similar to the one you used in the form example. You need to pick the right field in the report you’re opening (the CustomerID field in the CustomerPurchases report), and then match it to the field where you clicked the link (the ID field in the TotalsByCustomers report). Here’s what you need:

[CustomerID]=[Reports]![TotalsByCustomer]![ID]

As in the form example, this expression uses some wonky syntax with exclamation marks to tell Access how to find the TotalsByCustomers report.

Underneath the OpenReport action, type in Requery.

As in the form example, you need to refresh your report so that the filtering takes effect even if the form’s already open.

Close the macro window, and then choose Yes to save your changes when prompted.

You return to the report design window.

Switch to report view, and then try out your link.

Now you can click the link to drill down to the more detailed report.

As always, you can try this example out for yourself using the sample databases for this chapter.

![Here’s the CustomerPurchases report that profiles the selected individual’s spending habits. A string-building expression (="Products Purchased By " & [FirstName] & " " & [LastName]) puts the current customer’s name into the title.](http://imgdetail.ebookreading.net/data/2/0596527608/0596527608__access-2007-the__0596527608__httpatomoreillycomsourceoreillyimages2080255.jpg)