Richard R. Jones, CPA

Ernst & Young LLP

Gary L. Smith, CPA

Ernst & Young LLP

Accounting for inventory has been guided more by practice than by pronouncement. As advances in manufacturing processes have occurred, accounting practices have evolved to identify the applicable costs to be allocated to inventory. Authoritative accounting literature related to inventory accounting and financial reporting is not extensive. The accounting profession has made it clear that examining individual facts and circumstances is important when valuing inventory and applying the established standards.

Historical cost is the normal starting point to record inventory as an asset. In determining inventory cost, a cost flow assumption must be selected. Alternate valuation methods that are exceptions to the historical cost convention are used for certain specialized types of inventory (e.g., sales price less cost of disposal for precious metals, and net realizable value for trade-in inventory). The write-down of inventory to amounts below cost may be necessary due to factors such as damage or changing market conditions.

This chapter addresses inventory costing in greater detail by identifying the pertinent guidance in the authoritative accounting literature and by citing examples that illustrate the practical application of the fundamental principles. The chapter also explains the various types of inventory and practical ways to determine inventory quantities. Finally, the chapter explores effective internal control techniques and financial statement disclosure requirements.

Paragraph 25 of Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Concepts Statement No. 6, "Elements of Financial Statements," describes assets as "probable future economic benefits obtained or controlled by a particular entity as a result of past transactions or events." Inventory generally is acquired or produced for subsequent exchange. This utility or service potential justifies the classification of inventory as an asset of the enterprise that controls it. Normally, inventory is converted into cash or other assets during the operating cycle of the business. In fact, this process is what establishes the operating cycle. As a result, inventory typically is classified as a current asset for purposes of preparing a classified balance sheet.

The primary authoritative guidance addressing financial reporting for inventory is ARB No. 43, Chapter 4, "Inventory Pricing." It defines inventory of mercantile and manufacturing enterprises as:

The aggregate of those items of tangible personal property which (1) are held for sale in the ordinary course of business, (2) are in process of production for such sale, or (3) are to be currently consumed in the production of goods or services to be available for sale.

This definition makes it clear that the trading merchandise of a retailer or wholesaler—and the finished goods, work in process, and raw materials of a manufacturer—constitute inventory. ARB No. 43 specifically excludes from inventory long-term assets subject to depreciation accounting. Fixed assets such as buildings and equipment provide benefits that generally extend beyond the operating cycle and, therefore, are classified as noncurrent assets. ARB No. 43 notes that such assets should not be classified as inventory even if they are retired and held for sale.

The sale of inventory to customers is often the most significant component of revenue for a business enterprise. Matching inventory costs with the revenues received from the sale of the goods in order to determine periodic income is the major objective of inventory accounting. Incurred inventory costs that have not been charged against operations represent the carrying amount of inventory on the balance sheet. The costs allocated to goods on hand should not, however, exceed the utility of those goods. In other words, the recorded inventory balance should not exceed the total revenues less selling costs that will result when those goods are sold.

The methods used to determine and measure the flow of inventory costs should be consistent from period to period. The methods should be objective so that comparable results are produced by similar transactions, to allow for independent verification and to prevent manipulation of results of operations. Adequate disclosure should be made regarding the nature of the inventory and the basis on which it is stated.

Wholesalers and retailers typically acquire merchandise that is ready for resale to customers. Acquisition cost becomes the basis for carrying the inventory until it is sold.

In a manufacturing operation, a production process creates goods for sale to customers or for use in other operations. Manufacturing inventories often are categorized by stage of completion.

Goods to be incorporated into a product or used in the production process that have not yet entered the process are referred to as raw materials inventory. The output from one process can become the raw material for another process (e.g., subassemblies).

Goods typically are classified as work in process inventory as soon as they are drawn from raw materials stock and enter the manufacturing process.

Products that are complete and ready for sale are considered finished goods inventory.

Materials necessary for the manufacturing operation but not a significant component of the final product are known as supplies inventory. For example, small incidental screws may be considered supplies inventory, or oil used to lubricate a grinding machine may be considered supplies inventory. The ARB No. 43 specifically mentions manufacturing supplies as a type of inventory and notes that the fact that a small portion of the supplies may be used for purposes other than production does not require separate classification.

Arrangements for marketing, storage, distribution, and finishing of a company's products can result in goods being held by a party other than the owner. The consignee (party holding the goods) generally is precluded from recording the inventory because legal title is retained by the consignor and no exchange has taken place. The consignment inventory balance frequently is combined with the work in process or finished goods inventory shown on the consignor's financial statements. Examples include inventories held for sale in a retail store that have been consigned by the manufacturer, and components held by an outside machine shop to be used in a larger product by the consignor.

Some companies obtain goods accepted from customers in connection with sales of other products. These goods may or may not be similar to the items sold or other products of the seller. An example is a memory board accepted in trade by a computer manufacturer when upgrading customer equipment. Trade-in inventory should be valued at net realizable value, defined as estimated selling price less costs of disposal. The discount or allowance deducted from the list price of the goods sold is not an appropriate value to assign to the trade-in inventory, because the discount often pertains to marketing strategy and other factors not related to the trade-in items.

In connection with its collection efforts, a company may repossess its product from a customer. Companies that provide consumer financing often deal with repossessed inventory. The physical condition of the property may vary widely and will affect the company's decision regarding disposition (e.g., rework, offer for sale at a discount, scrap). Replacement cost is the primary method of valuing repossessed inventory. If replacement cost cannot realistically be determined, net realizable value should be used. Recording a repossessed item at the outstanding balance of the receivable from the customer is not appropriate, because this approach does not consider the condition and utility of the repossessed item.

A company may enter into a contract under which the customer provides specifications for producing goods, constructing facilities, or providing services.

Certain products—such as tobacco, spirits, livestock, and forest products—are held for an extended period of time until they are mature for sale or inclusion in a finished product. Recognized trade practice is to classify such inventory items as current assets despite the required aging process.

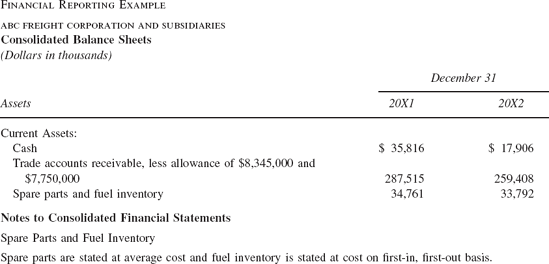

To service their customers, many companies (particularly equipment dealers and manufacturers) maintain a supply of spare parts for their products. Also, transportation companies hold spare parts to allow their fleets to operate continuously. Spare parts often are classified as inventory. When many small-value items are involved, companies amortize the related costs on a systematic basis. For more valuable spare parts, quantities are tracked and values are determined by the conventional inventory methods discussed in this chapter.

Many other types of products may be classified as inventory for financial reporting purposes. Examples include by-products (secondary products that result from the manufacturing process, particularly in the chemicals and the oil and gas industries), reusable items (such as beverage containers), and extractive products.

An important aspect of inventory accounting is to establish quantities. This section discusses the two basic methods used to determine the quantities of goods on hand, the periodic system and the perpetual system. In practice, hybrid methods often are used. Also, a company may use a periodic system for certain types of inventories and a perpetual system for others. For example, a steel company may use a perpetual system for work in process and for finished steel products but a periodic system for raw, bulk commodities such as iron ore.

A periodic system employs physical counts to determine physical quantities on hand. A perpetual system maintains detailed records to track quantities based on additions and usage. A perpetual system provides greater internal accounting control because it allows the user to identify and investigate differences between actual quantities on hand and the amounts the records indicate. The additional record-keeping requirements of a perpetual system generally are justified by the additional control given over high-value and off-site inventories. Further, perpetual systems provide improved management information for individual products that can enhance sales, marketing, and operation decisions. The greater availability and variety of automated systems have led to a proliferation of perpetual inventory systems in recent years.

Companies may use less sophisticated methods to determine inventory quantities at interim dates, compared to those used in connection with the year-end inventory valuation.

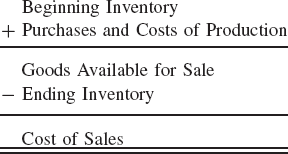

The most direct means of determining the physical quantity of inventory on hand is to count it. An inventory system that establishes quantities on the basis of recurring counts is known as a periodic system. After establishing quantities on hand, each unit is multiplied by its unit cost to determine its inventory value. Cost of sales is a residual amount obtained by subtracting the ending inventory amount from the cost of goods available for sale:

A periodic system is most likely to be used by a small company or for a department with low-value items that do not warrant more elaborate control procedures. A periodic system also is used for inventories for which reliable usage data cannot practicably be generated (e.g., certain supplies and extractive materials).

Written instructions that describe the procedures to be performed by the individuals participating in the count are an important part of the effort and should be prepared and distributed well in advance of the physical inventory date.

The instructions should cover each phase of the procedures and address these 11 matters:

Names of persons drafting and approving the instructions

Dates and times of inventory taking

Names of persons responsible for supervising inventory taking

Plans for arranging and segregating inventory, including precautions taken to clear work in process to cutoff points

Provisions for control of receiving and shipping during the inventory-taking period and, if production is not shut down, the plans for handling inventory movements

Instructions for recording the description of inventory items and how quantities are to be determined (e.g., count, weight, or other measurement)

Instructions for identifying obsolete, damaged, and slow-moving items

Instructions for the use of inventory tags or count sheets (including their distribution, collection, and control)

Plans for determining quantities at outside locations

Instructions for review and approval of inventory by department heads or other supervisory personnel

Method for transcribing original counts to the final inventory sheets or summaries

Physical inventory count teams should be familiar with the inventory items. The counts should be checked, or recounts should be performed, by persons other than those making the original counts.

The process to ensure that transactions are recorded in the proper accounting period is known as cutoff. For inventory, the general rule is that all items owned by the entity as of the inventory date should be included, regardless of location. For goods in transit, if they are shipped free on board (fob) destination, ownership does not pass from the seller to the purchaser until the purchaser receives the goods from the common carrier. For goods shipped fob shipping point, title passes from the seller to the purchaser once the seller turns the goods over to the common carrier.

In practice, purchases are recorded upon receipt, based on the date indicated on the receiving report. Inventory generally is relieved for items sold as of the date of shipment. In this manner, the accounting entries to record the purchase and sale of inventory correspond to the physical movement of the goods at the company. Assuming an accurate physical count of goods on hand is achieved, companies effectively eliminate cutoff errors by verifying that purchases have been recorded in the period of receipt and sales have been recorded in the period of shipment. This usually is accomplished by matching accounts payable invoices to receiving reports, and matching sales invoices to shipping documents. The procedure described above guarantees that both sides of the accounting entry are recorded in the same period. The inventory amount is recorded through the physical count and valuation, whereas the accounts payable/cost of sales amount is recorded through the matching procedure. This method implies all purchases are fob destination and all sales are fob shipping point. Although this is unlikely to be the case, the approach works in practice because goods in transit are typically not significant, and the procedure is applied consistently. Companies that have a significant volume of goods in transit and varying terms regarding transfer of ownership should scrutinize the inventory cutoff calculations. For example, a fob destination sale that was in transit at period end would be recorded prematurely using the method described above. As a result, pretax income would be overstated by the gross margin on the sale, accounts receivable would be overstated, and inventory would be understated. Such a situation normally is considered more of a revenue recognition issue (discussed in Chapter 17) than an inventory issue. The effect of a similar situation for a purchase would merely affect the balance sheet, because there is no margin involved for the buyer. In situations where a strict legal determination of ownership is impractical or other cutoff questions arise, the terms of the sales agreement, the intent of the parties involved, industry practices, and other factors should be considered.

Achieving an accurate cutoff is enhanced by controlling the shipping, receiving, and transfer activity during the physical count. Also, source documents (e.g., receiving reports, shipping reports, bills of lading) pertaining to goods shipped and received around the inventory date must be reviewed closely to verify that transactions have been recorded in the proper period.

Many businesses require frequent information regarding the quantity of goods on hand or the value of their inventory. A perpetual inventory system meets this need by maintaining records that detail the physical quantity and dollar amount of current inventory items. Technological advances such as scanners and low-cost computer applications have made automated perpetual inventory systems more practical and more popular. Their ease of use and their control over inventory quantities have enhanced the productivity of users. The records are updated constantly to reflect inventory additions and usage. Physical inventory counts are performed periodically to check the accuracy of the perpetual records. Discrepancies between the physical count and the quantities shown on the perpetual records should be investigated to determine the causes. Assuming an accurate physical count was achieved, the accounting records should be adjusted to reflect the results of the count. This entry is commonly referred to as the book to physical adjustment. The ability to isolate the book to physical adjustment is a perpetual system control feature not present in a periodic system.

In a perpetual inventory system, detailed records are maintained on an ongoing basis for each inventory item. The inventory balance is increased as items are purchased or inventoriable costs are incurred, and the balance is reduced as items are sold or transferred. Cost of sales reflects actual costs relieved from inventory. The level of sophistication of the records can vary dramatically, from manual entries posted directly to the general ledger to refined automated systems that use standard costs and detailed subsidiary records.

Cycle counting may be used with a perpetual inventory system to supplement other control procedures and to spread the physical counting effort throughout a period. A cycle count involves physically counting a portion of the inventory and comparing the quantity to that indicated by the perpetual records. Cycle counts test the reliability of the perpetual records. In connection with the ABC method of inventory control, in which higher cost items receive a greater degree of continuous control than other items, cycle counts are performed more frequently for high-cost items. Successful results from interim cycle counts can justify reliance on the perpetual records, and thereby eliminate the need to perform a companywide physical inventory at the fiscal year-end date. This approach generally is recommended in situations where unusual book to physical adjustments have not been identified during the interim cycle counts.

Implementation of effective accounting procedures and internal accounting controls over inventory quantities can protect the company's investment and reduce costs. A key objective is that goods or services are purchased only with proper authorization. To achieve this objective, some or all of the following 10 control procedures may be helpful:

Approval by designated personnel within specified dollar limits is required for requisitions and purchase orders.

Receiving, accounts payable, and stores personnel are denied access to purchasing records (e.g., blank purchase orders).

Purchasing personnel are denied access to blank receiving reports and accounts payable vouchers.

Purchase orders are compared to a control list or a file of approved vendors.

Purchase orders are issued in prenumbered order; sequence is independently checked.

Records of returned goods are matched to vendor credit memos.

Goods are compared to purchase orders or other purchase authorization before acceptance.

Unmatched receivers are investigated; unauthorized items are identified for return to the vendor.

Receipts under blanket purchase orders are monitored; quantities exceeding the authorized total are returned to the vendor.

Management approves overhead expense budget; variances from budgeted expenditures are analyzed and explained.

Another control objective is to prevent or detect promptly the physical loss of inventory. The following 16 controls may help to achieve this objective:

Responsibility for inventories is assigned to designated storekeepers; written stores requisition or shipping order is required for all inventory issues.

Perpetual records are regularly checked by cycle count or complete physical count.

Where no perpetual records are maintained, quantities are determined regularly by physical count, costing, and comparison to the inventory accounts.

Inventory counts and record keeping are independent of storekeepers.

Written instructions are distributed for inventory counts; compliance is checked.

Formal policies exist for scrap gathering, measuring, recording, storing, and disposal/recycling; compliance is reviewed periodically.

Cost of scrap, waste, and defective products is regularly reviewed and standards are adjusted.

Inventory adjustments are documented and require management approval.

Complete production is reconciled to finished goods additions.

Guards and/or alarm system are used.

Employees are identified by badge, card, and so on.

Employees are bonded.

Storage areas are secured against unauthorized admission and protected against deterioration.

Off-site inventories are stored in bonded warehouses.

Materials leaving premises are checked for appropriate shipping documents.

Estimation methods are used for retail inventories.

The cost principle that underlies today's financial accounting model holds that historical cost is the appropriate basis for recording and valuing assets. ARB No. 43 states:

The primary basis of accounting for inventories is cost, which has been defined generally as the price paid or consideration given to acquire an asset. As applied to inventories, cost means in principle the sum of the applicable expenditures and charges directly or indirectly incurred in bringing an article to its existing condition and location.

Section 20.5(b) of this chapter deals with the write-down of inventory to amounts below cost by applying the lower of cost or market concept. In such circumstances, the reduced amount is considered cost for subsequent accounting periods.

ARS No. 13, "The Accounting Basis of Inventories," states that "inventories are to be priced at cost, excluding nonmanufacturing costs." Determining what costs are inventoriable is a matter of professional judgment based on the broad guidance in the authoritative literature referred to above. ARB No. 43 contains these additional comments pertaining to the determination of inventory costs:

The exclusion of all overheads from inventory costs does not constitute an accepted accounting procedure.

Items such as idle facility expense, excessive spoilage, double freight, and rehandling costs may be so abnormal as to require treatment as current period charges rather than as a portion of the inventory cost.

General and administrative expenses should be included as period charges, except for the portion of such expenses that may be clearly related to production and thus constitute a part of inventory costs (product charges).

Products produced in individual units or batches, and requiring varying amounts of materials and labor (often to customer specifications) compared to other products, normally are costed using the job-order method. This technique is common in the furniture, printing, and robotics industries.

Costs of direct material and direct labor are assigned to specific jobs, based on actual usage. Usage information frequently is obtained from material requisition forms and labor time cards. Overhead typically is applied using a predetermined annual rate adjusted periodically to approximate actual costs.

Products produced in large quantities are normally costed using an averaging method called process costing. Companies in the textile, chemical, mining, and glass industries typically use process costing. Production runs are costed based on standard costs, which are the costs expected under efficient operating conditions. The total of all standard costs reported during each period is compared to actual costs incurred, based on general ledger account totals used to capture each cost category. Variances between standard costs and actual costs are analyzed and may be included in inventories or charged to expense, depending on the cause of the variance. No attempt is made to match costs of specific materials and labor to inventory units, because doing so would be highly impractical. A standard cost system can be effective in a process costing environment because of the relative predictability of unit costs. Standard costs can be developed based on each product's bill of materials and engineering specifications.

Materials contained in and traceable to a finished product are designated as direct materials. Because direct materials are a physical component of inventory items, and their cost is based on invoices from vendors, accounting for direct material costs is not difficult as long as quantities are tracked accurately. Freight and other costs of receiving materials also are inventoriable. Generally, freight-in is included as a portion of direct material, whereas receiving costs are included in the overhead pool. Paton & Paton indicate the cost of materials should be recorded net of related purchase discounts under the theory that income is not generated as a result of acquiring goods or services.[315]

For operational purposes, material price variances and usage variances are identified to highlight deviations from standard amounts. Use of the lower of cost or market criteria (described in Section 20.5(b) of this chapter) determines whether unfavorable variances or other factors such as spoilage require a write-down of the carrying amount for financial accounting purposes.

Payroll and employee benefits costs of employees incurred in the technical operations of converting raw materials to finished product are considered direct labor. It is more difficult to associate labor costs directly with inventory than to associate material costs in that way. Labor reporting systems are often the most cumbersome part of collecting inventory costs. Labor price variances and labor efficiency variances are identified to highlight the reasons for deviations from standard costs.

Overhead, often referred to as factory overhead or indirect manufacturing costs, consists of all costs—other than direct material and direct labor—directly related to and adding value to the manufacturing process.

ARB No. 43 states that general and administrative costs can be included in inventories only if they are clearly related to production and that selling expenses should never be included in the inventory. In addition, amounts of wasted materials (spoilage) regardless of whether it is normal or abnormal should be treated as a current period charge. For many companies, determining which costs are appropriate inventoriable costs under these criteria may be difficult. Costs typically included in the overhead pool are:

Indirect labor and employee benefits (e.g., factory supervision and maintenance).

Financial statement depreciation related specifically to assets utilized in the manufacturing process is an appropriate inventory cost. (Excess tax depreciation should not be included in inventory cost for financial reporting purposes.)

Receiving department.

Insurance costs, such as production workers' compensation and the cost of insuring the manufacturing facilities, are inventoriable. Costs related to product liability coverage and claims should not be included in inventory costs because they are related to goods that have already been sold, not those currently being produced or in inventory.

Factory utilities.

Other plant maintenance and repairs.

Other less obvious costs appropriate to charge to the overhead pool include (ARB No. 43 as amended by Statement of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS) No. 151):

Current service cost of pensions for production personnel are inventoriable. Prior service cost for production personnel may also be allocated to inventory.

Costs of warehousing and handling finished goods may be inventoriable for financial reporting purposes if the warehousing and handling is an integral aspect of bringing the goods to a salable condition (e.g., goods received in bulk at a warehouse that must be repackaged for final sale). In some situations, warehousing and handling costs are considered costs of disposal and are not inventoriable for financial reporting purposes.

Personnel department costs to the extent they relate to such activities as hiring and administering benefits of production personnel.

Purchasing department costs are inventoriable to the extent they relate to the acquisition of raw materials or production supplies by manufacturers or the acquisition of goods for resale by wholesalers or retailers.

Information systems processing costs that are specifically related to a manufacturing or cost accounting system may be included in inventory costs for financial reporting purposes. Data processing costs related to a general ledger or other financial accounting system should not be included in inventory costs.

Legal costs incurred for labor relations or workers' compensation issues are allocable to inventory for financial reporting purposes. Costs incurred in product liability matters should not be included in inventory costs.

Officers' salaries are inventoriable to the extent the officers' responsibilities are directly related to the production process (e.g., vice president of production or purchasing). The salary of a general officer, such as the chief operating officer, normally would not be inventoriable even though he has certain indirect responsibilities related to manufacturing operations.

SFAS No. 151 specifies that fixed overhead should be allocated to inventories based on the normal capacity of the productive facility.

Evaluating and documenting costs that may be capitalized as part of overhead cost requires judgment based on consideration of a number of factors, including a company's organizational structure and the nature of its accounting records. For example, a company that is highly decentralized may have all of its direct production costs segregated at its manufacturing facilities. The personnel, purchasing, and accounting functions related to manufacturing may all be located at the facility and their costs clearly identified. On the other hand, a highly centralized company may have all its personnel, purchasing, and accounting functions in a central location supporting sales and corporate functions as well as manufacturing. In this case, it is more difficult to establish and document a direct relationship to the production process. However, documenting a direct relationship is necessary to support including those costs in inventory under generally accepted accounting principles.

As described above, certain costs, such as selling expenses, abnormal costs, and a defined portion of general and administrative costs, are to be excluded from inventory and charged to operations as incurred. ARS No. 13 suggests relevant costs to be allocated to the overhead pool should be determined by considering a "cause-effect" relationship. "Causes are actions taken to manufacture products or to maintain the facilities and organization to manufacture products. The effects are the costs." The Research Study indicates that in conventional practice all costs associated with the selling function generally are treated as expenses of the period in which incurred, as are costs of general administration (excluding factory administration), finance, and general research. "Accounting for Research and Development Costs," FASB Statement No. 2, requires that all research and development costs encompassed by the Statement be charged to expense when incurred. FASB Statement No. 86, "Accounting for the Costs of Computer Software to Be Sold, Leased, or Otherwise Marketed," requires that all costs incurred to establish the technological feasibility of a computer software product be charged to expense as research and development. Once technological feasibility is established, software production costs are capitalized and amortized on a product-by-product basis. Capitalization of computer software costs ends when the product is available for general release to customers. Costs related to maintenance and customer support are expensed as incurred or when the related revenue is recognized, whichever occurs first. Costs incurred to duplicate the software, documentation, and training materials and to physically package the product for distribution are capitalized as inventory.

Selling costs are appropriately charged to expense as incurred, because such costs typically cannot be identified with individual sales and relate to goods previously sold rather than to inventory on hand. The question of deferring certain selling and marketing costs that relate to transactions not yet recognized for accounting purposes (i.e., in order to record the expense in the same period as the related revenue) is controversial and beyond the scope of this chapter. Nevertheless, if such costs are deferred, they should not be included with or classified as inventory. Numerous other types of costs raise questions about whether they should be included in the overhead pool or treated as a period cost. These costs include purchasing and other costs of ordering, quality control, warehousing, cost accounting, and carrying costs such as interest and insurance (on the inventory items and on the warehouse). The decision to include a cost in the overhead pool requires considerable judgment. In addition to using the "cause-effect" approach described earlier, challenging whether the cost adds value to the product is often useful. Observation of current practice indicates all of the above items except interest are included in the overhead pool by some companies and excluded by others. The FASB Statement No. 34, "Capitalization of Interest Cost," states, "Interest cost shall not be capitalized for inventories that are routinely manufactured or otherwise produced in large quantities on a repetitive basis because in the Board's judgment, the informational benefit does not justify the cost of so doing."

Including judgmental-type costs in inventory increases current assets and shareholders' equity. The effect on income of a particular period can be in either direction, depending on the relative inventory balances at the beginning and end of the period. However, for a growing company, a broadly defined overhead pool generally serves to increase income reported each period.

Because indirect production costs cannot be directly associated with a particular inventory unit, the costs are generally assigned to various units by using allocation methods. There are several means of allocating overhead costs to inventory and cost of sales. The traditional method has been to develop an overhead rate based on overhead cost per direct labor hour or direct labor dollar. This method allocates overhead to inventory and cost of sales in proportion to the amount of labor used. Other allocation bases may be more logical in certain circumstances. For instance, use of machine-hours may be a preferable method of overhead allocation for highly automated processes. Recording overhead costs by function and department can significantly improve the cost allocation process. Logical statistical methods can be established to allocate indirect costs. Such refinements can produce more meaningful results than use of a single plant-wide overhead rate. Increased accuracy and control results from using more specific and relevant overhead allocation methods.

Possible methods of allocating indirect costs include:

Indirect Cost | Allocation Basis |

Materials handling | Quantity or weight of materials |

Occupancy (depreciation, rent, property taxes, etc.) | Square-footage occupied |

Employment-related | Number of employees, labor hours, or labor dollars |

The level of sophistication in allocating indirect costs and determining overhead absorption rates can profoundly affect the inventory valuation and such other important matters as product margins and pricing.

"Accounting Changes Related to the Cost of Inventory," FASB Interpretation No. 1, indicates a change in composition of the elements of cost included in inventory is an accounting change. Reporting of such changes should conform with Accounting Principles Board (APB) Opinion No. 20, "Accounting Changes." Preference should be based on an improvement in financial reporting, not on the basis of the income tax effect alone.

Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) require reducing the carrying amount of inventory below cost whenever the selling price less cost of disposal of the goods is less than their cost. Impairment of inventory can occur through damage, obsolescence (technological changes or new fashions have reduced or eliminated customer interest in the product), deterioration, changes in price levels, excess quantities, and other causes. In Emerging Issues Task Force (EITF) Issue No. 00-14, "Accounting for Certain Sales Incentives," and EITF Issue No. 01-9, "Accounting for Consideration Given by a Vendor to a Customer or a Reseller of the Vendor's Products," the Task Force observed, "that the offer of a sales incentive that will result in a loss on the sale of a product may indicate an impairment of existing inventory under ARB No. 43." The lower-of-cost-or-market valuation method is designed to eliminate the deferral of unrecoverable costs and to recognize the reduction in the value of inventory when it occurs.

The guidelines for calculating the lower-of-cost-or-market adjustment, as defined in ARB No. 43, state:

As used in the phrase "lower of cost or market," the term "market" means current replacement cost (by purchase or by reproduction, as the case may be) except that:

Market should not exceed the net realizable value (i.e., estimated selling price in the ordinary course of business less reasonably predictable costs of completion and disposal); and

Market should not be less than net realizable value reduced by an allowance for an approximately normal profit margin.

Use of replacement cost as the starting point for the market valuation is intended to reflect the utility of the goods based on the cost required to produce equivalent goods currently. Replacement cost also is more practical than net realizable value for establishing a market value for raw materials and component parts because these items may not be sold separately or in their existing condition.

The ceiling of the market valuation described above is related to net realizable value to ensure that replacement cost valuation does not defer costs that will not be recovered by the ultimate selling price. For example, an inventory item with a net realizable value of $10 would not be carried above that amount even if its replacement cost exceeded $10. The floor of the market valuation is intended to eliminate any write-off of costs that will be recovered from the customer even though the replacement cost of the inventory is lower. For example, an item with a normal profit margin of 20 percent to be sold to a customer for $10 would not be carried at less than $8 even if its replacement cost was less than $8.

The lower-of-cost-or-market adjustment may be recorded for each inventory item or may be aggregated for the total inventory or for major inventory categories. The choice depends on the nature of the inventory and should be the one that most clearly reflects periodic income. Once selected, the same method should be applied consistently. Any comparisons of aggregate cost and market offset unrealized gains on certain inventory items against expected losses on other items (if such loss items exist) and, therefore, reduce the amount of the inventory write-down compared to the amount calculated on an item-by-item basis. Notwithstanding the principle of conservatism, the aggregate approach may be preferable when there is only one type of inventory or when no loss is expected on the sale of all goods because price declines of certain components are offset by adequate margins on other components. Similarly, the lower-of-cost-or-market procedure should be applied on an individual item basis for unrelated items and for inventories that cannot practically be classified into categories. Profitable margins on one product line should not be used to eliminate a lower-of-cost-or-market write-down for other unrelated products. ARB No. 43 specifically requires use of the item-by-item method of applying the lower of cost or market principle to excess inventory stock (quantity of goods on hand exceeds customer demand).

ARB No. 43 also states that "if a business is expected to lose money for a sustained period, the inventory should not be written down to offset a loss inherent in the subsequent operations."

Controls that can provide reasonable assurance that obsolete, slow-moving, or overstock inventory is prevented or promptly detected and provided for include:

Perpetual records show date of last usage; stock levels and usability are regularly reviewed.

Physical storage methods are regularly reviewed for sources of inventory deterioration.

Purchase requisitions are compared to preestablished reorder points and economic order quantities.

Potential overstock is identified by regularly comparing quantities on hand with historical usage.

Production and existing stock levels are related to forecasts of market and technological changes.

Bill of materials and part number systems provide for identification of common parts and subassemblies; discontinued products are reviewed for reusable components.

Work in process is periodically reviewed for old items.

Regular preparation and review of product line income statements can identify products that are losing money and may warrant a lower of cost or market write-down. Another procedure to highlight potential lower of cost or market concerns is to compare product carrying amounts to selling prices. A company can minimize lower of cost or market adjustments at year end by periodically comparing the carrying value of inventory items to net realizable value and adjusting to the lower figure.

The Task Force reached a consensus on EITF Issue No. 86-13, "Recognition of Inventory Market Declines at Interim Reporting Dates," that inventory should be written down to the lower of cost or market at an interim date unless:

Substantial evidence exists that market prices will recover before the inventory is sold.

In the case of last-in, first-out (LIFO) inventories, inventory levels will be restored by year end.

The decline is due to seasonal price fluctuations.

In SAB Topic No. 100, "Restructuring and Impairment Charges" (Topic 5-BB), the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) staff expressed its view, based on footnote 2 of ARB No. 43, that a write-down of inventory to the lower-of-cost-or-market at the close of a fiscal period creates a new cost basis that subsequently cannot be marked up based on changes in underlying facts and circumstances.

A SEC staff announcement (EITF Issue No. 96-9, "Classification of Inventory Markdowns and Other Costs Associated with a Restructuring") on the income statement classification of inventory markdowns associated with a restructuring indicated that the SEC staff recognizes that there may be circumstances in which it can be asserted that inventory markdowns are costs directly attributable to a decision to exit or restructure an activity. However, the staff believes that it is difficult to distinguish inventory markdowns attributable to a decision to exit or restructure an activity from inventory markdowns attributable to external factors that are independent of a decision to exit or restructure an activity. Further, the staff believes that decisions about the timing, method, and pricing of dispositions of inventory generally are considered to be normal, recurring activities integral to the management of the ongoing business. Accordingly, the SEC staff believes that inventory markdowns should be classified in the income statement as a component of cost of goods sold.

In 1984, the Accounting Standards Executive Committee (AcSEC) of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), in Section 6 of an issues paper, "Identification and Discussion of Certain Financial Accounting and Reporting Issues Concerning LIFO Inventories" (the AICPA Issues Paper), indicated that companies may apply the lower-of-cost-or-market provisions of ARB No. 43 to LIFO inventories on the basis of "reasonable groupings of inventory items." Further, it stated that in general a pool constitutes a reasonable grouping. Section 6 of the AICPA Issues Paper also indicates companies with more than one pool may aggregate pools for purposes of lower-of-cost-or-market determinations if the compositions of the pools are similar. The AICPA Issues Paper emphasizes the importance of "the character and composition" of the inventory in making lower-of-cost-or-market determinations. The Task Force also added the following caution: If the compositions of the pool are significantly dissimilar, they should not be aggregated.

The AICPA Issues Paper includes a discussion of the treatment of obsolete or discontinued products within the lower-of-cost-or-market review. The Task Force and AcSEC did not agree on this issue. AcSEC believes the item-by-item approach should be used for identified product obsolescence and product discontinuance, while the Task Force believes either the item-by-item approach or the aggregate-by-pool approach is appropriate. Because there was disagreement between the Task Force and AcSEC, companies can use either the item-by-item approach or the aggregate-by-pool approach for identified product obsolescence and product discontinuance. However, whatever approach used should be applied consistently.

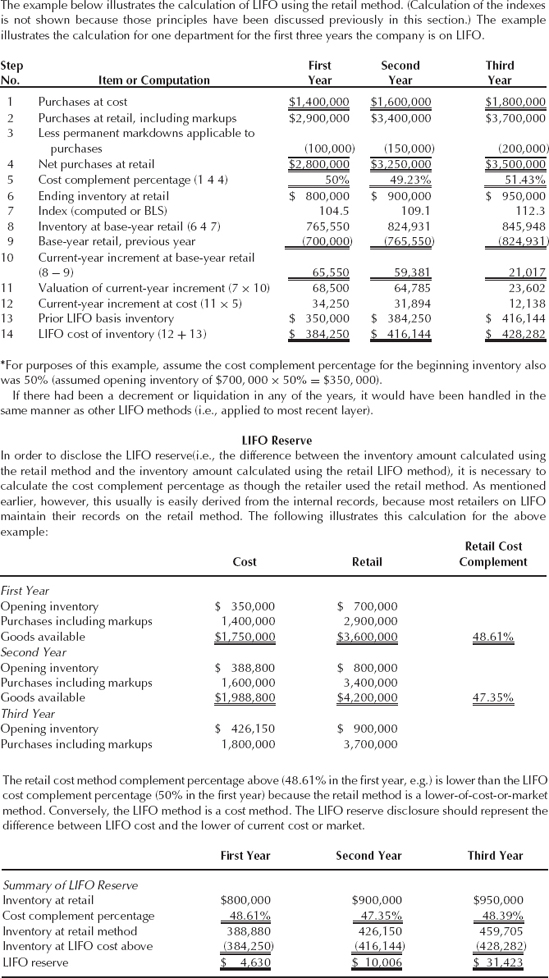

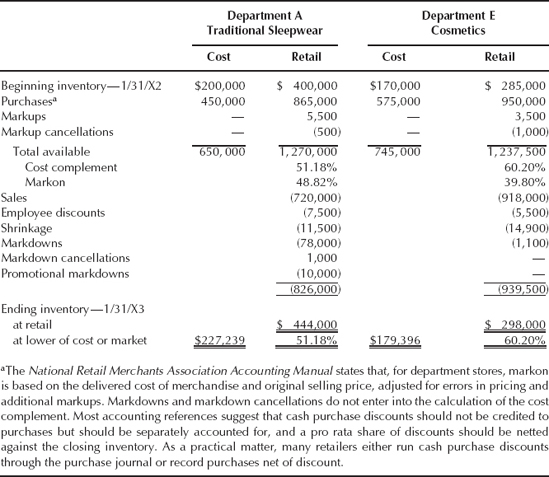

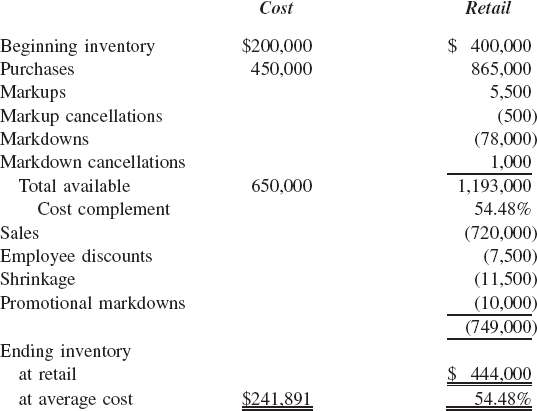

The retail method offers a simplified, cost-effective alternative of inventory valuation for department stores and other retailers selling many and varied goods. By using estimates of inventory cost based on the ratio of cost to selling price, it generally eliminates the procedure of referring to invoice cost to value each item. This ratio is often referred to as the cost ratio or cost complement. To avoid distortions arising from differing product mix and margins, a separate calculation is generally performed for each department. This step produces more accurate departmental costs and operating results. Also, because the types of products that constitute the inventory on hand at the balance sheet date may differ significantly from the proportion in which goods were purchased during the period, use of departmental cost ratios reduces the likelihood that these differences will improperly affect the inventory valuation.

Definitions of certain key terms used in the retail industry and important to the retail inventory method are:

Original retail. The price at which merchandise is first offered for sale

Markon. The difference between the retail price and the cost of merchandise sold or in inventory

Markup. An addition to the original retail price

Markdown. A reduction of original retail price

Markup cancellation. A reduction in marked-up merchandise that does not reduce retail price below the original retail price

Markdown cancellation. An addition to marked-down merchandise that does not raise retail price above the original retail price

Physical inventory counts (e.g., for year-end inventory taking) are initially priced at retail value (i.e., selling prices) and converted to cost using the cost ratio. The retail method also allows for periodic determination of inventory and cost of sales without the need for a physical count by means of a calculation similar to that shown in Exhibit 20.1. Retailers regularly use this type of calculation to value inventory at interim periods.

To perform the retail inventory calculations in a manner similar to that shown in Exhibit 20.1, a record of the cost and the retail value of the beginning inventory and of the current period purchases is kept (often referred to as the stock ledger). Net markups (markups less markup cancellations) are added to these amounts to determine the total goods available for sale on both the cost and retail bases. The cost ratio or cost complement calculated by dividing total cost of purchases by total selling price is used to reduce inventory at retail to cost. The markon percentage can be obtained by subtracting the cost ratio from 100 percent. The ending inventory at retail is obtained by subtracting current period sales, net markdowns (markdowns less markdown cancellations), and other reductions from the total goods available for sale on the retail basis. Finally, the ending inventory at retail is multiplied by the cost ratio to obtain the ending inventory at cost.

Figure 20.1. Example of retail inventory calculation. (Source: Wilson and Christensen, LIFO for Retailers, 1985

Note that the calculation in the exhibit excludes net markdowns from the computation of the cost ratio. Markdowns are deducted from the retail amount after the cost ratio is computed. This method values the ending inventory at an estimate of the lower-of-cost-or-market. ARB No. 43 acknowledges that this method is acceptable provided adequate markdowns are currently taken.

In contrast, the retail method is considered to approximate average costs if the calculation includes net markdowns in the computation of the cost ratio. This inclusion reduces the cost ratio denominator and thereby increases the ending inventory figure compared to the lower-of-cost-or-market methodology. To illustrate, the following calculations use the figures for Department A in the exhibit to compute the retail method variation that approximates average costs:

The retail LIFO valuation method is discussed in Section 20.6(c).

In certain cases, inventory items possess such widely accepted value and immediate marketability that an exception is made to the normal requirement that an exchange (e.g., sale) must occur for income to be recognized. Examples of inventories often valued above cost (i.e., at sales price less costs of disposal) include precious metals, farm products, minerals, and certain other commodities. It has become standard practice in these industries to value inventories based on selling prices rather than on cost. This is a practical solution to the difficulty of determining product cost for goods that are obtained from the ground rather than from manufacture.

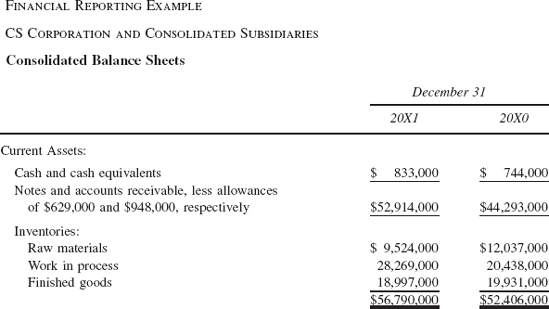

Financial Reporting Example

American Barrick Resources Corporation

Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements

(c) Inventories

Gold bullion inventory is valued at net realizable value.

ARB No. 43 indicates that to be valued above cost, inventory items must meet three criteria:

Inability to determine appropriate approximate costs

Immediate marketability at quoted market price

Unit interchangeability

Note that when inventory valuations are based on selling price, holding gains are recognized when the selling price increases and holding losses are recorded when the selling price decreases. When inventories are stated above cost, disclosure of this policy should be made in the financial statements.

Companies often hedge their exposure to commodity price fluctuations by entering into futures contracts or forward contracts. Theoretically, any gain or loss in the market value of the hedged item is directly offset by a change in the market value of the futures or forward contract. FASB Statement No. 133, "Accounting for Derivative Instruments and Hedging Activities," governs the accounting for hedge transactions and amended ARB 43, Chapter 4 (par. 526 of Statement No. 133) to require:

If inventory has been the hedged item in a fair value hedge, the inventory's "cost" basis used in the cost-or-market-whichever-is-lower accounting shall reflect the effect of the adjustments of its carrying amount made pursuant to paragraph 22(b) of FASB Statement No. 133, "Accounting for Derivative Instruments and Hedging Activities."

Statement No. 133 requires all derivative financial instruments to be carried at fair value. If the derivative qualifies for accounting as a hedge of the fair value of inventory, then the changes in the fair value of the derivative are recorded in current earnings. In addition, changes in the fair value of the inventory that occur during the period it is hedged are also recognized in income by adjusting the inventory's carrying amount. If the derivative does not qualify as a hedge of the fair value of the inventory, changes in the fair value of the derivative would be recorded in current earnings, while the carrying amount of the inventory would not be adjusted to reflect the change in its fair value.

As described above, replacement cost is the starting point for determining market value under the lower of cost or market valuation method. Replacement cost also is the primary method of valuing repossessed goods.

Certain inventory items for which cost or replacement cost is not determinable or is inappropriate for valuation purposes are valued at net realizable value, defined as estimated selling price in the ordinary course of business less reasonably predictable costs of completion and disposal. Scrap, by-products, and trade-in inventory are regularly valued at net realizable value.

Financial Reporting Example

Aileen, Inc.

Notes to Financial Statements

Obsolete inventory items are carried at net realizable value.

A frequently used technique to estimate the inventory balance without performing a physical count is the gross margin method. Although the gross margin method generally is not acceptable as the inventory valuation method for financial reporting purposes because of its reliance on estimated rather than actual cost information, it is useful for a variety of purposes, including these four:

Estimating the Inventory Balance at Regular Interim Periods. This might be required to calculate operating results and to calculate borrowing limits on loans collateralized by inventory. Companies with complicated manufacturing operations may not be able to take a complete physical inventory every quarter and, therefore, might require an estimating technique such as the gross margin method.

Preparing Budget Information. Budgets usually are centered on sales forecasts. The gross margin method is useful to estimate the cost of goods sold and inventory amounts based on the sales forecast.

Estimating the Value of Inventory Destroyed by a Casualty, Such as a Fire. Such calculations may be required to support insurance claims related to the loss.

Checking the Reasonableness of an Inventory Balance Determined Using a More Sophisticated Valuation Method.

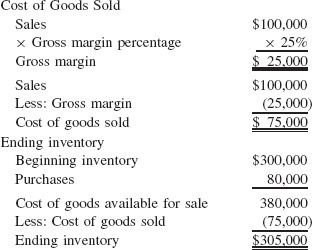

This method assumes that the gross margin percentage can be predicted with reasonable accuracy, based on results of prior periods or other calculations. This example demonstrates the estimation of an inventory balance using the gross margin method:

"Interim Financial Reporting," APB Opinion No. 28, recognizes that some companies use the gross margin method to estimate inventory and cost of goods sold for interim reporting purposes (e.g., quarterly reporting to the SEC). Such companies must disclose that this method is used and disclose any significant adjustments that result from reconciliations with the annual physical inventory.

Financial Reporting Example

XYZ Corporation and Subsidiaries

Notes to Condensed Consolidated Financial Statements (Unaudited)

Inventories

Substantially all inventories are valued using the LIFO method, which results in a better matching of current costs with current revenues. During interim periods, the valuation of inventories at LIFO and the resulting cost of sales must be based on various assumptions, including projected year-end inventory levels, anticipated gross margin percentages, and estimated inflation rates. Changes in economic events that are not presently determinable may lead to changes in the assumptions upon which the interim LIFO inventory valuation was made, which in turn could significantly affect the results of future interim quarters.

The following three general guidelines for assigning amounts to inventories acquired in a purchase business combination are contained in FASB Statement No. 141, "Business Combinations":

Finished goods and merchandise are valued at estimated selling prices less the sum of (a) costs of disposal and (b) a reasonable profit allowance for the selling effort of the acquiring enterprise.

Work in process is valued at estimated selling prices of finished goods less the sum of (a) costs to complete, (b) costs of disposal, and (c) a reasonable profit allowance for the completing and selling effort of the acquiring enterprise, based on profit for similar finished goods.

Raw materials are valued at current replacement costs.

Some business combinations accounted for as purchases are nontaxable. In those circumstances, if the acquired company accounted for inventories using the LIFO method and the acquiring company continues that LIFO election, the amounts reported as LIFO inventories for financial statement and for tax purposes will likely differ in the year of combination and in subsequent years.

Financial Reporting Example

LML Corporation

Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements

The book basis of LIFO inventories exceeded the tax basis by approximately $1,026,000 at both January 31, 20X1 and 20X0, as a result of applying the provisions of FASB Statement No. 141 to an acquisition completed in a prior year.

Some business combinations accounted for as purchases are also taxable transactions. In those instances, the portion of the purchase price allocated to inventories for financial reporting purposes may differ from that allocated to inventories for tax purposes. For example, when a "bargain purchase" is made, Statement No. 141 requires current values to be assigned to all current assets and the "bargain purchase" credit to be used to reduce the amounts otherwise assigned to noncurrent assets (except marketable securities). For income tax purposes, on the other hand, the "bargain purchase" credit usually is allocated to most of the assets acquired, including inventory.

To record inventory amounts accurately and ensure costs are assigned to inventory in accordance with the stated valuation method, controls should be implemented. These control procedures can be effective:

Cost accounting subsidiary records are balanced regularly to the general ledger control accounts.

Standard unit costs are compared to actual material prices, quantities used, labor rates and hours, overhead expenses, and proper absorption rate.

Variances, including overhead, are analyzed periodically and allocated to inventory and cost of sales; results are submitted to management for review.

Written policies exist for inventory pricing; changes are appropriately documented, quantified as to effect, and approved prior to change.

To provide assurance that goods and services are recorded correctly as to account, amount, and period, a company may select control procedures such as these eight:

Goods are counted, inspected, and compared to packing slips before acceptance.

Receiving reports are issued by the receiving/inspection department in prenumbered order; sequence is checked independently or unused receivers are otherwise controlled.

Services received are acknowledged in writing by a responsible employee.

Receiving documentation, purchase order, and invoice are matched before the liability is recorded.

Invoice additions, extensions, and pricing are checked.

Unmatched receiving reports and invoices are investigated for inclusion in the estimated liability at the close of the period.

Account distribution is reviewed when recording the liability or when signing the check.

Vendor statements are regularly reconciled.

In addition to valuing inventory properly at periodic reporting dates, an important objective is that the usage and movement of inventory be recorded correctly by account, amount (quantities and dollars), and period. To achieve this objective, these seven controls should be considered:

Periodic comparisons of actual quantities to perpetual records are made for raw materials, purchased parts, work in process, subassemblies, and finished goods.

Documentation is issued in prenumbered order for receiving, stores requisitions, production orders, and shipping (including partial shipments); sequence is checked independently.

Shipments of finished goods are checked for appropriate shipping documents.

Shipping, billing, and inventory records are reconciled on a regular basis.

Records are maintained for inventory on consignment (in and out), held by vendors, or in outside warehouses; these records are reconciled to reports received from outsiders.

Inventory accounts are adjusted for results of periodic physical counts.

Inventory adjustments are documented and require approval.

For cost-based inventory valuation methods, it is necessary to select an assumption of the flow of costs to value the inventory and cost of sales systematically. The reason is that the unit cost of items typically varies over time, and a consistent method must be adopted for allocating costs to inventory and cost of sales. As items are accumulated in inventory at different costs, a basis must be established to determine the cost of each item sold. The cost flow does not always match the physical movement of the inventory goods. ARB No. 43 recognizes that several cost flow assumptions are acceptable and that the major objective in selecting a method is to reflect periodic income most clearly. This emphasis on operating results rather than on financial position is contrary to the current direction of the FASB, which has, more recently, emphasized the balance sheet over the income statement in its Concepts Statements and recent pronouncements. ARB No. 43 also states that in some cases it may be "desirable to apply one of the acceptable methods of determining cost to one portion of the inventory or components thereof and another of the acceptable methods to other portions of the inventory."

Goods flow in the world outside financial reporting. Though Barden refers to "... the observable flow of cost, ..."[316] costs do not flow in the world outside financial reporting. In that world, a cost is a sacrifice, which is incurred at a moment in time. Once costs are incurred in the world outside financial reporting, that is the end of them. They pass into history; the costs are sunk; bygones are bygones. As Thomas says, "Historical costs don't change for the same reason Napoleon doesn't change: both are dead."[317] Costs flow only in the minds of accountants, and that is not observable. Selection of a cost flow assumption is merely selection of an inventory costing method. The use of cost flow assumptions prevents reporting on inventory from complying with the FASB's qualitative characteristic of representational faithfulness, which is not intended to include representations of states of accountants' minds.

The First-In, First-Out (FIFO) method assumes that costs flow through operations chronologically. Cost of sales reflects older unit costs whereas inventory is valued at most recent costs. In periods of rising prices, first-in, first-out can result in holding gains (also known as inventory profits) because older costs are matched against current sales. The ARS No. 13 concludes "that FIFO is the most logical assumed flow of costs if specific identification is not practicable." This conclusion is based on the pattern of the physical flow of goods and the valuation of inventory as close to current cost as is reasonably possible under the historical cost basis of accounting. The FIFO method is also relatively simple to apply.

In practice, the FIFO method is applied by valuing inventory items at the most recent costs of acquisition or production. For example, assume a dealer made these purchases of Item A during the year:

Date | Quantity | Unit Cost |

|---|---|---|

Jan. 6 | 1,000 | $4.00 |

Aug. 12 | 3,000 | 5.00 |

Dec. 18 | 2,000 | 6.00 |

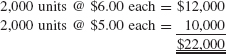

If 4,000 units of Item A were held in inventory at December 31, under the FIFO method they would be valued this way:

Note that, unlike the LIFO method, the FIFO method produces the same results whether the periodic or the perpetual inventory system is used.

Last-in, first-out (LIFO) is identified in ARB No. 43, Chapter 4, as one of the accepted methods of costing inventory and is widely used in practice. The LIFO method assumes the most recent unit costs are charged to operations. This values inventory at older costs. In periods of increasing prices, LIFO produces a higher cost of sales figure than FIFO or the average cost method and, accordingly, a lower income amount. Advocates of the LIFO method point out that in periods of continuous inflation, LIFO provides a better matching of costs and revenues than other cost flow assumptions because it matches current costs with current revenues in the income statement. Because proponents of LIFO believe that the income statement is more important to users of financial statements than the balance sheet, they give less weight to the counterargument that the LIFO method "understates" the inventory balances (in periods of rising costs) in relation to current costs. In addition, LIFO often improves the company's cash flow because it results in lower income taxes. This situation is attractive to companies seeking to reduce their income tax liability, and, as a result, many companies use the LIFO method for income tax purposes. The IRS regulations contain a "conformity requirement" that companies using LIFO for tax purposes must use LIFO for external financial reporting purposes, but it is acceptable for LIFO calculations to differ for book and tax purposes. Historically, IRS regulations have had a significant effect on LIFO techniques used for financial reporting purposes.

As mentioned previously, LIFO causes the inventory amount on the balance sheet to be carried at older costs. The theory supporting this method is that because a company needs certain levels of inventory to operate its business, carrying inventories at their initial cost is consistent with the historical cost principle. Under the LIFO concept, inventory levels are carried on the balance sheet at their original LIFO cost until they are decreased. Any increases (i.e., new layers) are added to the inventory balance at the current cost in the year of acquisition and are carried forward at that amount to subsequent periods. A liquidation (or decrement) of a LIFO layer occurs when the quantity of an inventory item or pool decreases. The liquidation causes older costs to be charged to operations, failing to achieve the LIFO objective of matching current costs and revenues. To summarize, as long as inventory quantities are maintained (i.e., not decreased), the older, generally low-cost layers are preserved. If inventory quantities decrease, older layers are liquidated and charged to operations, generally increasing earnings.

Principally because of the involved calculations related to inventory pools and layers, LIFO is more complex than other inventory valuation methods. As a result, LIFO may result in higher record-keeping costs and require more management attention and planning. Certain companies, particularly publicly held companies, may be concerned with investor reaction to the lower earnings reported under LIFO when prices are rising. The IRS rules that permit companies to make supplemental disclosures of FIFO earnings may help alleviate this concern.

There are two basic methods of determining LIFO cost: specific identification and dollar value (the latter method includes the double extension technique, the link-chain technique, the retail method, and other techniques discussed below).

The specific goods (or specific identification) method is normally the simplest LIFO approach to apply and understand. Inventory quantities and costs are measured in terms of individual units. Each item or group of similar items is treated as a separate inventory pool (e.g., a specific grade of tobacco).

The advantage of the specific goods method is that it is easy to conceptualize because LIFO costs are associated with specific items in inventory. This method has been used most frequently by companies that have basic inventory items, such as steel or commodities, and deal with a relatively low volume of transactions.

There are disadvantages, however, in using the specific goods method, especially if the inventory has a wide variety of items or if items change frequently (e.g., for technological reasons). In such circumstances, the specific goods method might become complicated, may prove costly to administer, and may produce unwanted LIFO liquidations.

The dollar-value method overcomes most of the disadvantages of the specific identification method. The distinguishing feature of the dollar-value LIFO method is that it measures inventory quantities in terms of fixed dollar equivalents (base-year costs), rather than quantities and prices of individual goods. Similar items of inventory are aggregated to form inventory pools. Changes in quantities and changes in product mix within a pool are ignored. Increases or decreases in each pool are identified and measured in terms of the total base-year cost of the inventory in the pool, rather than of the physical quantities of items.

One of the most important aspects of dollar-value LIFO is selecting the pools to be used in the computations. A careful assignment of inventory items to pools will avoid most of the limitations of the specific identification method noted above. Generally, the fewer the pools, the lower the likelihood of a liquidation and the lower the resulting taxable income. Fewer pools also minimize the administrative burden associated with accounting for LIFO inventories. The AICPA Issues Paper concludes that it is not feasible to formulate detailed guidance for selecting pools that could apply to all enterprises. It advises that the objective of LIFO inventory pooling is to group inventory items to match most recently incurred costs to current revenues, after considering the manner in which the company operates its business; establishing separate pools with the principal objective of facilitating inventory liquidations would not be considered acceptable. Items that comprise a similar or identical product sold by the enterprise should be included in the same pool. The existence of separate legal entities (e.g., subsidiaries), by itself, does not justify establishing separate LIFO pools for consolidated financial reporting purposes.

For tax purposes, LIFO is applied by individual corporations rather than consolidated groups. Each subsidiary must establish its own separate pools. If an affiliated group filing a consolidated income tax return has three subsidiaries in the same line of business, a single LIFO pool encompassing the operations of all three subsidiaries cannot be adopted for tax purposes even though one of the subsidiaries does central purchasing for all three. The IRS frequently challenges the nature and number of pools selected; both must be specified when a company applies to the IRS for an accounting change to the LIFO inventory method. Once a company has established the number of pools it will use in the year LIFO is adopted, changes can be made only with permission from the IRS. A method of pooling is considered an accounting method for tax purposes. Therefore, any change in the method of poolings requires IRS approval.

The broadest definition of a pool is the natural business unit pool. This includes, in a single pool, all inventories, including raw materials, work in process, and finished goods. This method is only available to companies—generally manufacturers and processors—whose operations consist of a single product line, or more than one if they are related. The natural business unit pool is attractive to many companies because the use of a single pool simplifies the LIFO calculations and reduces the number of layer liquidations.

Companies that do not qualify for natural business unit pooling or that wish to elect LIFO for only a portion of their inventory may elect the multiple pool method. Each of the multiple pools should consist of "substantially similar" inventory items.

Various computational techniques are used to apply the dollar-value method—the double-extension link-chain, internal indexes, the retail LIFO method (a variation of the link-chain technique) and other simplified external index techniques. These techniques have the objective of determining the base-year cost of the current-year inventory. The double-extension technique converts current-year amounts directly to base-year costs. The link-chain technique achieves the objective indirectly by developing an index based on the current-year cost increases and multiplying that index by the prior-year cumulative index. The internal index technique uses a representative sample of the entire population (e.g., 70 percent of all items in the pool or a statistical sample) that are double-extended to convert current-year amounts to base-year costs. The retail LIFO method is a dollar-value method that uses base-year retail value instead of base-year cost to compute inventory changes. The simplified external index technique applies 100 percent of the external index (e.g., price indexes published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS] to the current-year cost).

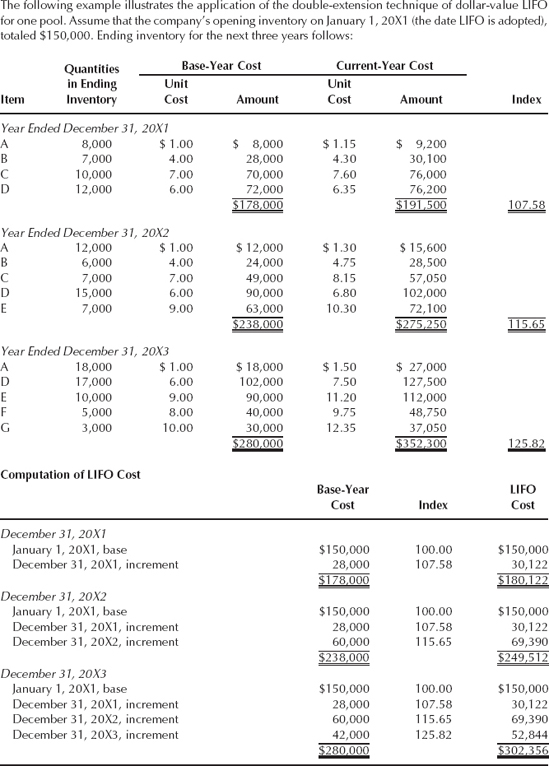

The double-extension technique extends ending inventory quantities twice—once at current-year costs (unit costs for the current period, determined using another method, typically FIFO) and once at base-year costs. This double extension procedure provides the current-year index (total current-year cost divided by total base-year cost).

To determine the net inventory change for the year, the ending inventory expressed in terms of base-year costs is compared to the beginning-of-the-year inventory expressed in terms of base-year costs. If the ending inventory at base-year costs exceeds the beginning inventory at base-year costs, a new LIFO layer has been created. The new layer is valued by applying the ratio of the ending inventory at current costs (using one of the approaches described later in this chapter) to the ending inventory at base-year costs. This ratio is generally referred to as LIFO index. If the ending inventory at base-year costs is less than beginning inventory at base-year costs, a LIFO liquidation has occurred. When a liquidation has occurred, decrements in base-year costs are deducted from the layers of earlier years beginning with the most recent prior year.

When an item enters the inventory for the first time, a company must either use its current cost or determine its base-year cost. Under IRS regulations, current cost must be used unless the company is able to reconstruct a base-year cost. The use of manufacturing specifications or other methods may allow a company to determine what the cost of a new item would have been in the base year. This effort may be worthwhile, because it may calculate a base-year cost that is lower than the current-year cost, most likely due to inflation in the cost of materials and labor. Use of a lower base-year cost in the LIFO calculations increases the current-year index and, thereby, lowers the inventory balance and pretax income. In other words, by reconstructing a base-year cost for new items, the impact of LIFO is normally maximized.

Companies that use the double-extension technique must retain indefinitely a record of base-year unit costs of all items in inventory at the beginning of the year in which LIFO was adopted, as well as any base-year unit costs developed for new items added in subsequent years. Exhibit 20.2 is an example of the LIFO double-extension technique.

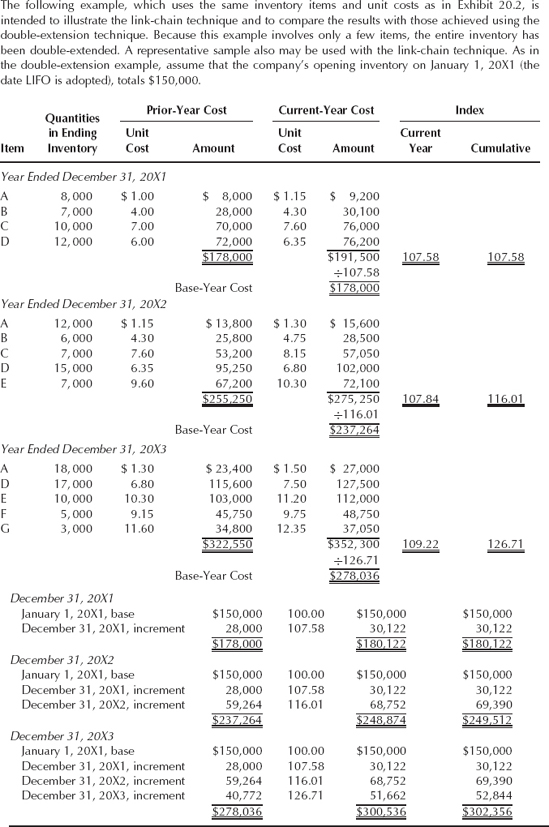

The double-extension technique can prove cumbersome, particularly when the base year extends back a number of years. Changes in product specifications and manufacturing methods are common in many industrial companies. The link-chain method eliminates the burden of reconstructing base-year costs and so is a more efficient means of computing LIFO cost. In determining a LIFO index, an IRS rule of thumb holds that at least 70 percent of the total value of the pool should be matched to the prior-year costs to achieve a representative sample. If a statistical, random sampling technique is used, fewer items may be matched to obtain acceptable results.

Under the link-chain technique, the ending inventory is double- extended at both current-year unit costs and prior-year unit costs. The respective extensions are then totaled, and the totals are used to compute a current-year index. This current-year index is multiplied by the prior-year cumulative LIFO index to obtain a current-year cumulative index. Total current-year costs are divided by the current-year cumulative index to determine base-year costs. If ending inventory stated at base-year cost exceeds beginning inventory stated at base-year cost, a new LIFO layer has been created. The new layer is valued by applying the applicable cumulative index (using one of the approaches described later in this chapter) to the increments stated at base-year cost. If ending inventory stated at base-year cost is less than beginning inventory stated at base-year cost, a LIFO liquidation has occurred. The double extension and link-chain techniques produce identical results in the year LIFO is adopted. In subsequent years, however, changes in inventory mix and differences in the way new inventory items are handled usually create at least minor differences.

When a liquidation has occurred, decrements in base-year costs are deducted from the layers of earlier years, beginning with the most recent prior year.