Robert L. Royall II, CPA, CFA, MBA

Ernst & Young LLP

Francine Mellors, CPA

Ernst & Young LLP

The editors wish to acknowledge the previous contributions to this chapter by Norman Strauss, CPA, of the Stan Ross Department of Accountancy, Zicklen School of Business.

In January 1992, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) began deliberating issues related to derivatives and hedging transactions. After much controversy, the FASB issued Statement No. 133, "Accounting for Derivative Instruments and Hedging Activities," in June 1998. It was discussed at over 100 FASB meetings, was exposed for comments twice, and was the subject of two different congressional hearings. Legislation had even been proposed in an attempt to override the Statement.

Statement No. 133 was effective for financial statements for fiscal years beginning after June 15, 2000, and calendar-year companies were required to apply the new standard on January 1, 2001. The transition adjustments resulting from adoption were required to be recognized in income and other comprehensive income (stockholders' equity), as appropriate, as a cumulative effect of an accounting change. The Statement superseded Statement No. 80, "Accounting for Futures Contracts," Statement No. 105, "Disclosure of Information about Financial Instruments with Off-Balance-Sheet Risk and Financial Instruments with Concentrations of Credit Risk," and Statement No. 119, "Disclosures about Derivative Financial Instruments and Fair Value of Financial Instruments," and amends the hedging sections of Statement No. 52, "Foreign Currency Translation." It amended Statement No. 107, "Disclosures about Fair Value of Financial Instruments," to include in Statement No. 107 the disclosure provisions about concentrations of credit risk from Statement No. 105.

The FASB considered various approaches to reconcile and extend the existing hedge accounting guidelines in Statements Nos. 52 and 80. However, the Board decided that such an approach was not practical and instead decided to pursue a new approach to applying hedge accounting. The four basic underlying premises of the new approach are:

Derivatives represent rights or obligations that meet the definitions of assets (future cash inflows due from another party) or liabilities (future cash outflows owed to another party) and should be reported in the financial statements.

Fair value is the most relevant measure for financial instruments and the only relevant measure for derivatives. Derivatives should be measured at fair value, and adjustments to the carrying amount of hedged items should reflect changes in their fair value (i.e., gains and losses) attributable to the risk being hedged arising while the hedge is in effect.

Only items that are assets or liabilities should be reported as such in the financial statements. (The Board believes gains and losses from hedging activities are not assets or liabilities and, therefore, should not be deferred.)

Special accounting for items designated as being hedged should be provided only for qualifying transactions, and one aspect of qualification should be an assessment of the expectation of the effectiveness of the hedge (i.e., offsetting changes in fair values or cash flows).

The Board has announced that Statement No. 133 on derivatives and hedging is simply an interim step on the road to accomplish its "vision" of having all financial instruments measured at fair value.

The key changes are:

All derivatives are carried at fair value.

Hedge accounting continues, but the accounting varies based on the type of hedge: fair value, cash flow, or net investments in foreign operations.

Specific criteria to be able to use hedge accounting are established.

The ineffective portion of a hedge is recognized in income and not deferred, thus creating potential volatility in income.

Cash flow hedges are recognized in other comprehensive income, thus creating potential volatility in equity.

Hedging certain foreign currency transactions is easier under the new rules. The definition of a derivative is now broader.

New disclosures are required.

Statement No. 133 applies to all entities. However, special provisions govern not-for-profit entities and other entities (e.g., employee benefit plans) that do not report earnings as a separate caption in a statement of financial performance.

An understanding of the FASB's complex definition of a derivative is essential to be able to apply the new Statement. While Statement No. 133 takes several paragraphs to define a derivative, it reflects the following key concepts:

A derivative's cash flows or fair value must fluctuate and vary based on the changes in one or more underlying variables.

The contract must be based on one or more notional amounts or payment provisions or both, even though title to that amount never changes hands. The underlying and notional amount determine the amount of settlement, even regardless of whether a settlement is required.

The contract requires no initial net investment, or an insignificant initial net investment.

The contract can readily be settled by a net cash payment, or with an asset that is readily convertible to cash.

Examples of derivatives include swaps, options, futures, some forward contracts, swaptions, caps, collars, and floors. In a significant change from prior practice, certain items such as convertible debt held as an investment, some commodity purchase agreements, some structured notes, and some insurance contracts also are derivatives or contain embedded derivatives.

An "underlying" is a variable or index whose market movements cause the fair market value or cash flows of a derivative to fluctuate. An underlying may be a price or rate of an asset or liability but is not the asset or liability itself. Examples of underlyings include London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) in an interest rate swap, the price of crude oil in a forward crude oil contract, or the spot exchange rate of a foreign currency in a foreign currency option. When the underlying fluctuates, the market value of the derivative and the amount of cash projected to be exchanged between the parties change. Some derivatives have multiple underlyings.

While the underlying is the variable in a derivative, the notional amount is the fixed amount or quantity that determines the size of the change caused by the movement of the underlying. Examples include the stated principal amount in an interest rate swap, the stated number of bushels in a wheat futures contract, the number of barrels in a crude oil swap contract, and the contracted amount of Euros in a foreign currency forward.

Derivatives are unique in that the parties do not have to initially invest in or exchange the notional amount. Though some contracts can settle through physical delivery (e.g., futures and forwards), a derivative really represents an investment in the change in value caused by the underlying, and not an actual investment in the notional amount or quantity of the underlying. The notional amount is just a factor in determining the size of the potential changes in fair value of the derivative. For example, in a typical receive fixed and pay floating interest rate swap with a notional amount of $10 million, no one pays or receives $10 million. The $10 million notional amount is only multiplied by the difference in the fixed interest rate and the floating rate to determine how much cash must be paid between the parties and by whom. As the notional amount gets larger, the greater the effect that changes in the underlying will have on the amount exchanged between the parties.

Some derivatives will require an initial net investment as compensation for time value (such as an option premium) or for "off-market" terms (such as a premium on an interest rate swap which pays the holder a higher fixed rate than current market rates would indicate). Such contracts are still considered "derivatives" in the scope of Statement No. 133.

Typically, a derivative can be settled in cash rather than by the delivery of the underlying item. However, Statement No. 133 will extend this concept to include contracts that can be settled in assets that are readily convertible into cash (e.g., Treasury securities, marketable equity securities, commodities) or for which a market mechanism exists to facilitate liquidation of the contract for a net cash payment even though the contract itself does not contemplate a net cash settlement (e.g., futures contracts).

To meet the criterion of an asset that puts the recipient in a position not substantially different from net settlement, the asset must be readily convertible to cash. (By cash, the FASB generally means the functional currency of the reporting entity.) The FASB believes that to be readily convertible into cash, the asset must have interchangeable (fungible) units and quoted prices available in an active market that can rapidly absorb the quantity held by the entity without significantly affecting the price. Thus, the asset being received must be actively traded. Under this concept, a forward contract entered into by a rental car company to buy automobiles would not be a derivative; but a forward contract to buy unleaded gasoline may (see specific exclusions, which follow) be a derivative, because unleaded gasoline is actively traded.

Additional examples will be helpful in understanding the types of instruments that will be included in the definition. Consider first a contract for the purchase of a U.S. Treasury security that provides for a settlement date at a date that would be later than normal for the purchase of such an investment. Because a Treasury security can be readily converted to cash, this contract would be considered a derivative even though the only means of settlement is by delivery of the security. Similarly, a foreign currency forward contract for a highly liquid currency (e.g., Japanese yen) also would be considered a derivative, even if it is required to be settled by delivery of the currency. However, a foreign currency forward contract that requires the delivery of an illiquid currency (e.g., Venezuelan bolivars) would not be considered a derivative under Statement No. 133. (Delivery of a foreign currency is not delivery of "cash" unless that currency is the functional currency of the reporting entity.) Making these distinctions will require considerable judgment.

The effect of defining a derivative by characteristics rather than by contract types has often surprising implications. Companies may hold stock purchase warrants, participating in alliances with Internet start-ups. These warrants meet the definition of a derivative if they can be settled by delivery of shares in a publicly traded company, and those shares once delivered are not restricted from trading for the first 31 days. Typically, warrants to purchase shares in an Internet start-up company satisfy the definition of a derivative after that company undergoes an initial public offering (IPO). Ordinary commodity contracts, in addition to commodity futures contracts, also satisfy the definition of a derivative if the commodity has interchangeable (fungible) units and quoted prices available in an active market. Therefore, contracts to purchase or sell crude oil, natural gas, corn, cotton, gold, aluminum, and a host of other commodities will likely satisfy the definition, and the fair value of such contracts will fluctuate if the transaction price is fixed or partially fixed. As the next section explains, such commodity contracts may be able to be exempted from the provisions of Statement No. 133 if they are deemed to be "normal."

The FASB believed that certain contracts that otherwise meet the literal definition of a derivative should not be accounted for as derivatives. Accordingly, Statement No. 133 specifically excludes several types of contracts from the scope and, therefore, the methods of accounting for these contracts will not be affected. These include:

"Regular-way" (normal) securities trades (e.g., purchases or sales of securities that settle in the normal course for the particular security).

Normal purchases and sales of assets other than financial instruments (i.e., commodities) for which net settlement is not intended and physical delivery is probable (and so documented) that are in quantities expected to be used or sold over a reasonable period in the normal course of business (e.g., the forward purchase of unleaded gasoline by a rental car company for the quantity it expects to use in the next month). Evaluating what is "normal" will be unique to each entity and may be influenced by industry customs for acquiring and storing commodities, an entity's operating locations, past trends, expected future demand, and other contracts for delivery of similar items.

Certain insurance contracts[369] that compensate the holder only as a result of an identifiable insurable event (generally, traditional life insurance and property and casualty contracts).

Certain financial guarantee contracts that provide for payments to reimburse the guaranteed party for a loss because the debtor fails to pay. Other financial guarantee contracts could be derivatives under the new Statement if they provide for payments to be made in response to a change in an underlying, such as a decrease in a referenced entity's credit rating (i.e., credit derivatives).

Contracts issued by an entity in connection with stock compensation arrangements (e.g., performance-based stock option plans). (These contracts could be derivatives to the recipient.)

Contracts indexed to the entity's own stock and classified in stockholders' equity (e.g., rights, warrants, and options). (These contracts may be derivatives to the counterparty.)

Contracts issued by an entity as contingent consideration in a business combination. (These contracts could be derivatives to the recipient.)

Nonexchange-traded contracts with underlyings based on the following:

Climatic, geological, or other physical variables (e.g., heating degree days, level of snowfall, seismic readings).

The price or value of a nonfinancial asset or liability of one of the parties that is not readily convertible to cash or does not require delivery of an asset that is readily convertible to cash (e.g., an option to purchase or sell real estate that one of the parties own, or a firm commitment to purchase or sell machinery). This exception applies only to nonfinancial assets that are unique and only if a nonfinancial asset related to the underlying is owned by the party that would not benefit under the contract from an increase in the price or value of the nonfinancial asset. For example, an option to buy real estate at a fixed price is not a derivative because the owner (i.e., prospective seller) would not benefit from the contract if the price of the real estate increases above the option price.

Specified volumes of sales or service revenues of one of the parties (e.g., royalty agreements).

Derivatives that serve as impediments to sales accounting (e.g., a residual value guarantee of a leased asset by the lessor that prevents the lease from being a sales-type lease or a call option that enables a transferor of financial instruments to repurchase the transferred assets and prevents sales accounting for the transfer).

Occasionally, derivatives are embedded in other instruments, such as a debt instrument where the interest payments fluctuate with changes in the Standard and Poor's (S&P) 500 index or where the principal amount is affected by the price of gold. Generally, if the economic characteristics and risks of the embedded derivative are clearly and closely related to the economic characteristics and risks of the host contract, it is outside the scope of the new Statement, and the accounting for the derivative is based on the accounting for the host instrument. When the economic characteristics and risks of the embedded derivative are not clearly and closely related to the economic characteristics and risks of the host instrument, however, the embedded derivative should be separated and accounted for as a derivative instrument under Statement No. 133.[370] (The bifurcation provisions do not extend to a derivative embedded in another derivative, such as a cancelable swap.)

In the case of an equity indexed note (e.g., principal indexed to the S&P's 500 index), changes in the stock indices are not clearly and closely related to the interest rate based economic characteristics of debt, so the derivative would have to be bifurcated and separately accounted for using the new rules. However, a note with interest payments tied to changes in the debtor's credit rating (which could not result in a negative yield) would meet the "clearly and closely related" test and would not have to be accounted for as a derivative, because interest rates are closely aligned with the credit rating of the debtor. Similarly, typical callable and putable bonds also are not subject to Statement No. 133 because the changes in value of the call and put features are clearly and closely related to market interest rate changes, like the bond itself.

Statement No. 133 does not necessarily treat the issuer and recipient of certain contracts in the same way. In several instances, the recipient of a contract will be considered to have a derivative contract, while the issuer of the same contract will not. For example, an investor in convertible debt that includes an embedded equity call option which is not clearly and closely related to a debt instrument will be required to bifurcate the option and separately account for it as a derivative. Issuers of convertible debt, however, will not be considered to have issued a derivative because the option can be settled only by issuance of the issuer's own equity securities.

Statement No. 133 includes numerous examples illustrating the "clearly and closely related" criterion to help preparers determine if bifurcation is necessary.

The Statement requires all derivatives to be recorded on the balance sheet at fair value. The guidance in Statement No. 107 is to be applied in determining fair values.

Fair value represents the amount at which an asset (liability) could be bought (incurred) or sold (settled) in a current transaction between willing parties; that is, other than in a forced or liquidation sale. (The ambiguity of that definition is discussed in Section 1.3(b)(v).) The requirement to obtain fair values for all derivatives on a regular (at least quarterly) basis is a significant change from prior practice.

Statement No. 133 allows "special accounting" for the following three categories of hedge transactions:

Hedges of changes in the fair value of assets, liabilities, or firm commitments (referred to as fair value hedges)

Hedges of variable cash flows of recognized assets or liabilities, or of forecasted transactions (cash flow hedges)

Hedges of foreign currency exposures of net investments in foreign operations

Changes in the fair value of derivatives not meeting the criteria to use one of these three hedging categories must be recognized in income. For those that meet the criteria, Statement No. 133 provides an approach to hedge accounting that differs from prior practice. The three hedge types, the criteria, and the special accounting provisions for derivatives that meet the criteria are discussed in further detail in the following sections. However, for background purposes, the following is a brief overview of the special accounting within Statement No. 133:

To even be considered as a hedge, in addition to other criteria, a derivative instrument must be "highly effective" in offsetting exposure due to changes in fair value or cash flows of the hedged item.

In a fair value hedge, changes in the fair value of both the derivative and the hedged item attributable to the risk being hedged are recognized in earnings. Thus, to the extent the hedge is perfectly effective, the change in the fair value of the hedged item will be offset in income with only the net effect of the hedge impacting earnings.

In a cash flow hedge, to the extent the hedge is effective, changes in the fair value of the derivative are recognized as a component of other comprehensive income in stockholders' equity until the hedged transaction affects earnings. The accounting for the hedged transaction is unaffected by the placement of the hedge.

In a hedge of foreign currency exposures in a net investment in a foreign operation, to the extent the hedge is effective, the change in the fair value of the derivative is treated as a translation gain/loss and recognized in other comprehensive income offsetting other translation gains/losses arising in consolidation. Thus, for this hedge type, the new rules are similar to prior practice.

If a derivative is highly effective but not perfectly effective and does not exactly offset the changes in fair value or cash flows of the hedged item or transaction, the ineffective portion must be recognized in income when the change in fair value of the derivative is recognized on the balance sheet.

Statement No. 133 clarifies that a hedging instrument generally can be only a derivative, as defined by the new Statement. A nonderivative instrument (e.g., a Treasury note) cannot be designated as a hedging instrument except when it results in a foreign currency transaction gain or loss and is designated as hedging the foreign currency exposure of a net investment in a foreign operation or of changes in the fair value of a foreign currency-denominated firm commitment.

One of the most difficult aspects of the Statement is determining when the special accounting for hedges is allowed. The basic premise for all three types of hedges is that a derivative must be expected to be highly effective in achieving offsetting changes in fair value attributable to the risk being hedged. In other words, the change in the value of the hedging instrument must offset the change in the value of the hedged item. The FASB has been purposefully vague in providing guidance as to how much ineffectiveness is permitted before a hedge relationship can no longer be deemed highly effective. The Statement refers to prior guidance on correlation (i.e., Statement No. 80), in which an 80 percent effective hedge is considered to be highly effective, but anything less effective is considered "ineffective." Further, the Statement requires a company to define how it will measure the effectiveness of a hedge relationship, at both the inception of the hedge and over the entire life of the relationship.

Under Statement No. 133, hedge effectiveness affects more than just whether the derivative qualifies for hedge accounting. In a change from prior practice, hedge ineffectiveness, the amount by which the change in the value of the hedge does not exactly offset the change in the value of the hedged item, will often be recorded in income immediately, even for highly effective derivatives that qualify for hedge accounting. For example, if a hedged item's fair value increases by $10, but the derivative only offsets the change by $8, there is $2 of hedge ineffectiveness. Likewise, if the derivative's fair value changes by $10, but the hedged item's fair value changes by only $8, there also is $2 of hedge ineffectiveness. The extent to which the ineffectiveness is recognized in earnings differs depending on whether a hedge is a fair value or cash flow hedge.[371]

Statement No. 133 permits the exclusion of a portion of a change in value of a derivative from the effectiveness assessment. The change in value of the excluded component of the fair value of the derivative is considered to be inherently ineffective and recognized in earnings immediately. For example, companies may exclude the time value of options and differences between forward and spot rates that exist at the inception of a hedge with a forward contract from their assessment of hedge effectiveness, because there is no offsetting change in the value of the hedged item for this element of the hedge. These costs can be viewed as the cost of entering into the hedge, similar to an insurance premium when obtaining insurance. As a result, these costs are effectively excluded from the special accounting for the hedge. However, unlike prior practice in which such costs could be recorded in income ratably over the life of a hedge, as one might account for an actual insurance premium, the Statement requires that they be recognized in income based on changes in their fair value because these costs are components of the overall fair value of the derivative. The result is a much more volatile earnings recognition process for these hedging costs, even though the amounts of such costs are known at the outset of a hedge.

To illustrate this concept, assume in order to hedge an anticipated transaction six months from now, a company enters into a six-month Euro forward foreign currency contract when the forward exchange rate is Euro 1.1:$1 but the spot rate is Euro 1.0:$1. The anticipated transaction will actually be consummated at the spot rate on the date of the transaction, and as it gets closer to the date of the transaction, the forward rate and the spot rate will converge. If at the date of the hedged transaction, the spot rate is still Euro 1.0:$1, the fair value of the derivative will have changed due to the passage of time by the Euro 0.1 change in the forward rate. However, the present value of expected cash flows of the hedged transaction will have changed only due to the passage of time and not because the spot rate has changed. Thus, the change in value of the derivative due to the initial difference between the forward rate and the spot rate is inherently ineffective at hedging the anticipated transaction. As a result, the Statement allows companies to exclude this difference from their assessment of hedge effectiveness. However, the derivative itself, the forward contract, must always be carried at fair value on the balance sheet. Therefore, the difference in the forward and the spot rates at inception, commonly referred to as the premium or discount, is effectively part of the cost of the hedge that is recognized in income over the life of the contract as the contracts change in fair value and the forward and spot rates converge.[372]

A similar effect occurs with the time value of options. At inception, the value of an option consists of time value and perhaps intrinsic value, if the option is already in-the-money. This time value decays as an option approaches its expiration date, while intrinsic value may increase or decrease depending on movements of the fair value of the underlying item. As the intrinsic value increases, the holder of the option will desire to exercise it. If exercised, the value of an option is based primarily on its intrinsic value. Thus, when exercised, a derivative has changed in value because the time value component of the option has decreased from its original fair value, but the hedged item will not have experienced an offsetting change in value that can be related to the time value decay. Therefore, the time value of the option is inherently ineffective in most common hedge designs. Again, the Statement allows companies to exclude the time value of the option from their assessment of hedge effectiveness, but the option must always be carried at its fair value including any time value that may exist. This results in changes in the fair value of the time value of the option being recognized in income over the life of the option. This recognition pattern will be different from the straight-line amortization method that has generally been previously used. Most bothersome for many companies is that time value can actually increase in certain periods leading to an even greater future decay, particularly when the underlying experiences highly volatile movements or the fair value of the underlying moves closer to the exercise price of the option.

In contrast to the concept of derivatives with inherent ineffectiveness, hedge ineffectiveness can also result when there is a less than perfect matching of the derivative and the hedged item. A derivative that has a similar, but not identical, underlying basis with the hedged item illustrates this condition. For example, using a Dutch guilder-based forward to hedge a Belgian currency exposure, or using a LIBOR-based swap to hedge debt tied to commercial paper rates, results in some hedge ineffectiveness. Ineffectiveness also arises when differences in the terms of the derivative and the hedged item exist, even when the underlying bases are the same. Such differences might include the notional amounts, rate reset dates, maturity, cash flow receipt/payment dates, or, in the case of commodity hedges, delivery location differences. For example, foreign currency swaps that call for quarterly settlements will not perfectly hedge anticipated royalty payments that occur monthly. Likewise, fixed rate debt that pays interest on February 1 and August 1 cannot be perfectly hedged with a swap with cash flow dates set to be April 1 and October 1.

In an effort to relieve companies from having to constantly assess whether their derivatives are perfectly effective, Statement No. 133 outlines certain criteria for derivatives that, if met, permit an assumption that the hedge is perfectly effective. These criteria are sometimes referred to as the shortcut method, because when these criteria are met, the hedge is considered perfectly effective and the accounting is significantly simplified. However, the ability to use the shortcut method is limited, because the Statement only provides for the shortcut method with respect to interest rate swaps and commodity forward contracts.

An entity may assume that a hedge of a forecasted purchase of a commodity with a forward contract will be highly effective and that there will be no ineffectiveness if:

The forward contract is for purchase of the same quantity of the same commodity at the same time and location as the hedged forecasted purchase.

The fair value of the forward contract at inception is zero.

Either the change in the discount or premium on the forward contract is excluded from the assessment of effectiveness or the change in expected cash flows on the forecasted transaction is based on the forward price for the commodity.

Statement No. 133 also provides specific guidelines as to when an interest rate swap can be assumed to be perfectly effective. All of the following conditions must be met:

The notional amount of the swap matches the principal amount of the interest bearing asset or liability.

The fair value of the swap at the inception of the hedge is zero. The formula for computing net settlements under the swap is the same for each net settlement (i.e., the fixed rate is the same throughout the term, and the variable rate is based on the same index and includes the same constant adjustment or no adjustment).

The interest-bearing asset or liability is not prepayable at other than its fair value.[373]

The index on which the variable leg of the swap is based matches the benchmark interest rate designated as the interest rate risk being hedged for that hedging relationship.

Any other terms in the interest-bearing instrument or swap are typical of those instruments and do not invalidate the assumption of no ineffectiveness.

In addition, if the hedge is a fair value hedge, the swap must have the following:

The expiration date of the swap must match the maturity date of the interest-bearing asset or liability.

There can be no floor or ceiling on the variable interest rate of the swap.

The interval between repricings of the variable leg of the swap must be frequent enough to justify an assumption that the variable payment or receipt is at a market rate (generally, three to six months or less).

The short-cut method is available only for cash flow hedges of variable rate assets and liabilities. It is not available for hedges of forecasted transactions that result from the maturity and reissuance of short-term fixed-rate assets and liabilities, such as commercial paper programs. In a cash flow hedge, the swap must have the following:

All interest receipts or payments on the variable-rate asset or liability during the term of the swap must be designated as hedged, and no interest payments beyond the term of the swap are designated as hedged.

There can be no floor or cap on the variable interest rate of the swap unless the variable-rate asset or liability has a floor or cap. In that case, the swap must have a floor or cap on the variable interest rate that is comparable to the floor or cap on the variable-rate asset or liability. The Statement indicates that "comparable" does not mean equal. However, by illustrating comparability, the FASB has indicated that a strict algebraic relationship should exist between the barriers. The Statement indicates that if a swap's variable rate is LIBOR and an asset's variable rate is LIBOR plus 2 percent, a 10 percent cap on the swap would be comparable to a 12 percent cap on the asset.

The repricing dates must match those of the variable-rate asset or liability.

Through the Derivatives Implementation Group (DIG) interpretations, the FASB has insisted that the use of the term match—in the criteria required to apply the shortcut method-means "exactly match." A company cannot use the shortcut method if it merely comes close to matching some of these criteria. In addition, the shortcut method cannot be analogized to any other types of derivative instruments.

Another key benefit, in addition to not having to periodically evaluate effectiveness, is the accounting simplicity of the shortcut method. As always, the derivative is recorded at fair value as either an asset or a liability. But with the shortcut method, a company can assume that the hedged item changes exactly as much as the derivative's fair value changes. In a fair value hedge, the hedged item is adjusted exactly the same amount as the derivative, with no impact on earnings. In a cash flow hedge, other comprehensive income is adjusted exactly the same amount as the derivative, with no impact on earnings. With respect to interest rate swaps, each periodic cash settlement is accrued in the income statement as an adjustment to interest income or expense, as typically was done prior to Statement No. 133. In many ways, the shortcut method mirrors the prior "synthetic instrument" accounting in the income statement, but the balance sheet is grossed up as a necessary consequence of reflecting the derivative at fair value.

The following criteria apply to all derivatives and hedged items, as indicated below:

At inception, there must be formal documentation (designation) of the hedging relationship and the entity's risk management objective and strategy for undertaking the hedge, including identification of the derivative, the related hedged item, the nature of the particular risk being hedged, and how the hedging instrument's effectiveness will be assessed (including any decision to exclude certain components of a specific derivative's change in fair value, such as time value, from the assessment of hedge effectiveness). Note that because designation is required at inception, the use of hedge accounting is, in essence, optional (i.e., management could elect not to designate a derivative as a hedge). However, this determination must be made at inception and cannot be retroactively applied after the changes in fair value of the derivative are known.

At inception and on an ongoing basis, the hedge must be expected to be highly effective as a hedge of the identified item. The effectiveness in achieving offsetting changes to the risk being hedged must be assessed, consistent with the originally documented risk management strategy.

If the derivative provides only a one-sided offset against the hedged risk (i.e., an option contract), the increases (or decreases) in the fair value or cash flows of the derivative must be expected to be highly effective in offsetting decreases (or increases) in the fair value or cash flows of the hedged item.

For a written option designated as a hedge, the combination of the hedged item and the written option must provide at least as much potential for gains as a result of favorable changes as exposure to losses from unfavorable changes. In other words, a percentage favorable change in the fair value of the combined instruments provides at least as much gain as would the loss incurred from an unfavorable change of the same percentage. (The impact of this requirement is that most written options will not qualify for hedge accounting.)

If similar assets, liabilities, firm commitments, or transactions are aggregated and hedged as a portfolio, the individual items that make up the portfolio must share the risk exposure designated as being hedged in approximately the same magnitude.

The hedged item presents an exposure that could affect reported earnings.

The hedged item cannot be related to an asset or liability that is, or will be, remeasured with the changes in fair value reported currently in earnings (e.g., a debt security classified as trading or its interest cash flows).

The hedged item cannot be related to a business combination or the acquisition or disposition of subsidiaries, minority interests, or equity method investees, or to an entity's own equity instruments classified in stockholders' equity.

Interest rate risk cannot be hedged for a held-to-maturity debt security or for its cash flows; however, changes in fair value attributable to an option component of the security, credit risk, or foreign exchange risk can be hedged.

For a nonfinancial asset or liability or its cash flows, the designated risk being hedged must be the risk of changes in fair value or cash flows for the entire hedged asset or liability and not the price risk of a similar asset in a different location or of a major ingredient.[374]

If the hedged item is a financial asset or liability, a recognized loan servicing right, or the financial component of a nonfinancial firm commitment, or the cash flows of such an item, the designated risk being hedged must be (1) the risk of changes in the overall fair value or cash flows for the hedged asset or liability, (2) the risk of changes in fair value or cash flows attributable to changes in the designated benchmark interest rate (referred to as interest rate risk), (3) the risk of changes in fair value or cash flows attributable to changes in the related foreign currency exchange rates, (4) the risk of changes in fair value or cash flows attributable to both changes in the obligor's creditworthiness and changes in the spread over the benchmark interest rate with respect to the hedged item's credit sector at inception of the hedge (referred to as credit risk), or (5) some combination of the risks enumerated in (2) through (4).

A nonderivative instrument, such as a Treasury note, generally cannot be designated as a hedging instrument.[375]

As described above, one of the hedgeable risks permitted under Statement No. 133 is the risk of changes in the designated benchmark interest rate. Statement No. 133 as amended currently permits two benchmark interest rates to be hedged, and they must be specifically designated and documented at the inception of the hedge:

Interest rate swap rates based on the LIBOR, a rate considered by international financial markets as inherently liquid, stable, and reliable, and therefore commonly used in many swaps and other hedging instruments, and

The risk-free rate, which in the United States is considered to be the interest rate on direct Treasury obligations of the U.S. government. (In foreign markets, the rate of interest on sovereign debt may be considered the benchmark interest rate.)

While companies may wish to designate other benchmark interest rates, such as prime, Fed Funds, or commercial paper indices, the Statement does not permit it. Rather, companies may use derivatives based on nonauthorized benchmarks and designate the derivative as a hedge of the risk of changes in the overall fair value or cash flows of the hedged item.

A derivative can hedge a portion or percentage of a hedged item, even though it cannot hedge ingredients or components of nonfinancial items. For example, a company seeking to hedge its exposure to changing gasoline prices can hedge 50 percent of its gasoline on hand or a specific volume of expected sales in the month of June, even if it cannot hedge the risk of price fluctuations of the crude oil component of gasoline.[376] Similarly, a proportion of the total or a portion of the life of a hedged financial asset or liability can also be designated as a hedged item, including one or more selected contractual cash flows. For example, a company will be able to designate either 50 percent of its 10-year debt or the first five years' cash flows as the hedged item in a hedging relationship. However, only the designated cash flows are considered in the effectiveness assessment, rendering most previous partial-term hedging strategies to fail to qualify as hedges under Statement No. 133.

The process of documenting and identifying the hedging relationship, the derivative, the hedged item, the nature of the particular risk being hedged, and how the hedging instrument's effectiveness will be assessed is a much more extensive requirement than the prior hedge accounting requirements, which merely contemplated "designating" the hedge.

How a hedge is designated at inception can significantly affect the presentation of the hedge in the financial statements and its effect on earnings. In some cases, designating a specific derivative as a fair value hedge or as a cash flow hedge will be optional, but because the accounting for each type of hedge is different, the designation decisions are important. For example, a company that keeps a portfolio of short-term investments and has long-term fixed rate debt outstanding would be able to designate an interest rate swap entitling it to receive a fixed interest rate and to pay a variable interest rate as either a cash flow hedge of the future interest income from its short-term investments or as a fair value hedge of its long-term debt obligation. In either case, the derivative would protect the company from the effects of declining interest rates. Hedge documentation must be performed at the inception of the special accounting. Management cannot wait to see whether it is more advantageous to designate the hedge one way or another.

In addition to the highly effective criteria, the Statement includes specific criteria for both the derivative and the hedged item. The three hedge types share some common criteria, while other criteria are specific to the type of hedge (i.e., fair value, cash flow, or net investment). Unless the hedge and the hedged item meet all of the applicable criteria, the hedge fails to qualify for the "special accounting," and the change in fair value of the derivative must be recognized in income as it occurs without consideration of the change in value of any related exposure. Similarly, the "special accounting" will only be able to be applied while the criteria are met. As a result, if the criteria, even the elective criteria such as designation, cease to be met during the life of a derivative or hedged item, the "special accounting" permitted by Statement No. 133 will cease. In addition, if the criteria fail to be met because the hedged forecasted transaction is probable of not occurring, any gains or losses from the derivative that have not yet been included in earnings are immediately charged or credited to income.

In addition to the criteria discussed above, each of the three hedge types also has additional criteria. The additional criteria, as well as the approach to the financial reporting for each type of hedge, are discussed in the following sections.

Fair value hedges protect against the changes in value caused by fixed terms, rates, or prices. As an example, a company with fixed rate debt enters into an interest rate swap to receive a fixed rate of interest and pay a variable rate to protect against paying higher than market interest rates if interest rates decline. As a result, if rates decline, the company will be able to refinance its debt at the lower interest rates without incurring a loss from the extinguishment of the debt (because it will be offset by an increase in the value of the swap). Alternatively, the company may view the swap, when coupled with the debt, as effectively providing the company with an obligation to make interest payments at a variable rate.

As another example, a refinery, concerned that crude prices may fall while it is contracted to buy 1 million barrels of crude oil at a fixed price, enters into a short crude oil futures contract. If prices decrease, the company pays an above market price under its purchase contract, but realizes a gain in value of its futures contract that compensates the company as if it had effectively sold the crude at the prior, now above market, price.

In both of the above examples, the company's future cash flows for interest and crude, respectively, were fixed. The derivative protected the company from subsequent changes in value of the hedged item attributable to changes in market prices.

In a significant change to the conventional "deferral" approach for hedging transactions, Statement No. 133 requires companies to recognize in income, in the period that a change in value occurs, gains or losses from a derivative designated as a fair value hedge. In addition, changes in the fair value of the hedged item (i.e., the asset, liability, or firm commitment), to the extent they are attributable to the risk designated as being hedged, would also be simultaneously recognized in income and as an adjustment to the carrying amount of that item. In theory, perfectly effective hedges will produce perfectly offsetting income statement entries, so that only the desired effect of the hedge impacts net income. However, any aspect of a fair value hedging relationship that is ineffective will be immediately reflected in income. An unrealized gain or loss on a hedged asset, liability, or firm commitment that existed prior to the establishment of the hedge would not be recognized, nor would changes in value of a hedged item during the life of a hedge that are not attributable to the risk being hedged. A hedge can be entered into or removed by undesignating the derivative as a hedge at any time for an asset, liability, or firm commitment.

For hedged items that absent the hedge would be measured at fair value with changes in fair value reported in other comprehensive income (e.g., available-for-sale debt securities), the adjustment of the hedged item's carrying amount (attributable to the risk being hedged) should be recognized in income rather than other comprehensive income while the hedge exists.

Adjustments to the carrying amounts of hedged items that are recorded as a result of a fair value hedging relationship must be subsequently accounted for as any other adjustment of the basis of the asset or liability. For example, if the hedged item is a commodity that will be used in a manufacturing process, the adjustments to the carrying amount of the raw material inventory as a result of the fair value hedge relationship will be included in inventory as would any other component of the cost of the commodity. If the hedged item is a fixed income financial instrument, such adjustments to its carrying amount will be treated as adjustments to the contractual interest rate provisions and amortized as a yield adjustment of the hedged item. To simplify the mechanics of the special hedge accounting, the Statement indicates that amortization of the resulting adjustments of hedged financial instruments is not required to begin until the hedge is removed.

The new accounting treatment represents an even more radical change for hedges of firm commitments than it does for hedges of existing assets or liabilities. Fair value hedges of an asset or liability result in fair value adjustments to amounts that already exist on the balance sheet. Fair value hedges of firm commitments, however, cause an asset or liability to be recorded that had previously not been recognized under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). Under the Statement, in addition to recognizing the change in fair value of the derivative, entities also recognize, as assets or liabilities, changes in the fair value of the firm commitment that arise while a hedge of the firm commitment exists and that are attributable to the risk being hedged. The new rules create this asset or liability for only the period the commitment is hedged. Thus, if the hedge is entered into subsequent to entering into the firm commitment, the recorded asset or liability for the firm commitment may not equal the actual fair value of the commitment.

An example will help put the unique accounting for firm commitments into perspective. Consider a company that has a commitment to purchase a piece of machinery in six months from a German manufacturer at a contractually determined amount of Euros. The company decides to hedge its foreign currency obligation by entering into a foreign currency forward contract to purchase the required Euros at the date they will be needed at a predetermined exchange rate. During the life of this fair value hedge, the change in value of the foreign currency forward contract will be recorded in income. In addition, the change in value of the foreign currency component of the firm commitment will also be recorded in income. To the extent the hedge is effective, the amounts recorded in income will offset, resulting in no income statement effect. However, the firm commitment will be carried on the balance sheet at an amount representing the change in value of its foreign currency component during the periods the hedge is in place. Upon delivery of the machine, the carrying amount of the firm commitment will become a part of the carrying amount of the machine and will be included in future depreciation of the cost of the machinery. This aspect, namely how the gain or loss on the hedged firm commitment is recognized in earnings, must be anticipated and formally documented at the inception of the hedge.

Statement No. 133 defines a firm commitment as an agreement with an unrelated party, binding on both parties, and usually legally enforceable, under which performance is probable because of a sufficiently large disincentive for nonperformance. It further indicates that all significant terms of the transaction should be specified in the agreement, including the quantity to be exchanged, the fixed price, and the timing of the transaction. The definition is similar to that included in Statement No. 80 for futures contracts and has been applied in prior practice to foreign currency hedges of firm commitments.

Examples of contractual commitments satisfying the definition of a firm commitment include:

A commodity purchase agreement that provides for both the quantity to be delivered and the price to be paid at a specific date

Contract for the purchase of a fixed asset at a specified delivery date and price denominated in a foreign currency (In this case, the exchange rate is not fixed, but the amount of foreign currency is.)

License or royalty agreement that provides for fixed periodic payments at specific time intervals. (A license or royalty agreement that specifies a unit price, but does not include a minimum quantity would not meet the definition even though future sales that will result in the royalty are probable.)

Intercompany contracts generally would not qualify under the definition as a firm commitment because they are with related parties. However, many intercompany contracts could still be hedged as an anticipated or forecasted transaction as a cash flow hedge.

The recognition of hedge ineffectiveness in a fair value hedge is relatively straightforward. The ineffectiveness is recognized in the income statement as a result of the requirement to recognize both the change in fair value of the derivative and the change in fair value related to the hedged risk of the hedged item. If the offsetting changes in fair value do not equal, the difference must be recognized in earnings. Note that if the difference is significant, the transaction may not meet the hedging criteria ("highly effective") at all, and thus the derivative would be marked to market through income with no offset for changes in the fair value of the hedged item.

This fair value hedge accounting approach has been described by the FASB as achieving a result similar to the prior practice of deferring hedging gains and losses. However, the result will only be the same when changes in the value of the hedged item equal or exceed the offsetting gain or loss from the derivative. In addition, the similarity will generally end at a comparison of the income statement results. The balance sheet will differ significantly as a result of the recognition of derivatives at fair value and the recognition of related changes in value of the hedged items.

Statement No. 133 allows the foreign currency exposure relating to the following to be hedged in fair value hedge:

An unrecognized firm commitment

A recognized asset or liability (including an available-for-sale security)

The FASB decided to specifically prohibit hedge accounting if the related asset or liability is or will be measured at fair value, with changes in fair value reported in earnings when they occur, such as securities classified as "trading" under Statement No. 115. Any asset or liability that is denominated in a foreign currency and remeasured into the functional currency under Statement No. 52 is permitted to be hedged as either a fair value hedge or a cash flow hedge, because such accounting is not deemed equivalent to measuring such assets or liabilities at fair value through earnings. However, foreign currency-denominated assets and liabilities must still be accounted for in accordance with Statement No. 52 (i.e., remeasured at spot rates with the changes in the carrying amount reported currently in earnings even when they are the hedged item in a fair value hedge).

Unrecognized firm commitments would qualify for fair value hedge accounting, because firm commitments are not recognized on the balance sheet and accordingly are not measured at fair value that would affect earnings. Similarly, available-for-sale securities also would qualify for fair value hedge accounting, because in accordance with Statement No.115, changes in the fair value of available-for-sale securities are not accounted for currently in earnings, but in other comprehensive income.

The following examples illustrate the accounting for fair value hedges for a company that has adopted Statement No. 133 on January 1, 2000:

Example 1—No Ineffectiveness. On July 15, 2000, the Company issues a $10 million, 9% fixed rate note due on July 15, 2004, with semiannual interest payments on the anniversary dates of the issue. On the same day, it also enters into a $10 million notional amount receive fixed and pay floating interest rate swap. The swap calls for semiannual settlement between January 15, 2001, and July 15, 2003. The Company receives payments based on 8% and pays LIBOR. There is no exchange of a premium at the initial date of the swap. The documentation of the hedge relationship would be as follows:

Date of Designation—July 15, 2000.

Hedge Instrument—$10 million notional amount, receive fixed (8%) and pay floating (LIBOR) interest rate swap, dated July 15, 2000, payable semiannually through July 15, 2003.

Hedged Item—$10 million, 9% note payable due July 15, 2003 (comprised of a benchmark LIBOR rate of 8% plus a 1% credit spread).

Strategy and Nature of Risk Being Hedged—Changes in the fair value of the interest rate swap are expected to perfectly offset changes in the fair value of the fixed rate debt due to changes in the benchmark LIBOR swap interest rate.

How Hedge Effectiveness Will Be Assessed—Because the terms of the debt and the fixed rate payments to be received on the swap coincide (notional amount, payment dates, term, and rates), the hedge will be considered perfectly effective against changes in the fair value of the debt over its term. The hedge is structured to qualify for use of the shortcut method, and by definition there is no hedge ineffectiveness or a need to periodically reassess the effectiveness. The hedge meets the criteria for a fair value hedge.

On January 15, 2001, the benchmark LIBOR swap rate falls to seven percent. Due to the decrease in rates, the fair value of the swap increases to $226,000, and the carrying value of the debt should be increased to $10,226,000, such that the gain in value of the swap has offset the loss in value of the debt due to changes in the benchmark LIBOR swap rate. Thus, on January 15, 2001, the following entries are necessary:

To recognize the change in the fair value of the debt attributable to the hedged risk.

During the six months ended January 15, 2001, the Company also would have paid interest on its debt of $450,000, received a fixed rate payment from the swap counterparty of $400,000, and made a payment based on LIBOR to the swap counterparty. These payments would all be netted in the interest expense account, resulting in interest expense at the variable rate of LIBOR plus the spread between the LIBOR swap rate and the actual rate on the debt. Note that while the hedge is in effect, the adjustment to the carrying amount of the debt does not have to be amortized.

On July 15, 2001, assume that the benchmark LIBOR rate has remained the same. Due to the additional payments that have been made and the passage of time, the fair value of the debt attributable to the benchmark LIBOR swap rate would decrease to $10,184,000 and the positive fair value of the swap would decline to $184,000. Accordingly, the following entry would be required to adjust the carrying amount of the swap to its fair value and record the change in the fair value of the debt attributable to interest rate changes:

To recognize the change in the fair value of the debt attributable to the hedged risk.

To recognize the change in the fair value of the swap.

As during the prior semiannual period, the Company will have offsetting fixed interest rate payments and receipts and make a payment of a LIBOR rate of interest on the notional amount of the swap. These amounts will be netted in interest expense to result in a variable rate of interest expense.

The Company will follow the same procedure of constantly adjusting the carrying amount of the swap to its fair value and adjusting the carrying amount of the debt by the same amount, to reflect its change in its fair value attributable to the hedged risk. Because the hedge was designed to be perfectly effective, the periodic adjustments to the carrying amount of the debt and the swap will be for the same amounts. The Company's net interest expense will be equal to the LIBOR payments made to the swap counterparty plus the spread between the fixed rates paid and received. Thus, the effect on income is the same as prior practice for swaps, but the balance sheet effect is different. Had the swap been partially ineffective, then the effect on income also could have differed from prior practice.

The accounting can become more complex when ineffectiveness is present. This will occur whenever the hedging relationship cannot be considered perfectly effective; that is, when differences between the hedging instrument and the hedged item exist. The following example illustrates the accounting under the Statement in this situation:

Example 2—Ineffectiveness Present. On January 1, 2000, a gold mining operation enters into a fixed price contract (i.e., a firm commitment) to deliver 100 troy ounces of gold on June 30, 2000, to a customer in London at a price of $310/troy ounce, the published June 30, 2000, forward price of gold on January 1, 2000, in London. The firm commitment is not accounted for as a derivative contract because it qualifies for the "normal sales" exception of Statement No. 133. The Company would have preferred for the sales contract to have been at the market price on the date of delivery, but as a concession to its customer offered it a fixed price contract. To hedge against the potential increase in gold prices, on January 1, 2000, the Company buys a NYMEX (New York Mercantile Exchange) futures contract (100 troy ounces) at a futures price of $300/troy ounce for delivery in June. The NYMEX contract requires delivery in New York. Assume that the forward curve is flat and that the six months' futures price equals the spot price in New York on January 1, 2000. The $10/troy ounce price difference relates to the London versus New York delivery locations.

The Company's strategy is that, because it is concerned that prices will go up between now and delivery in June, the long futures contract effectively eliminates the risk of being locked into a sales price over the next six months at the January 1 price. Through the hedge, the Company has effectively unlocked the sales price. If prices do go up over the next six months, the Company will benefit from the hedge, but the fair value of the firm sales commitment will decline because it will then be at a below market price. However, the Company is accepting some "basis" risk in that it is assuming that the NYMEX price will fluctuate consistently with the London price over the next six months. To the extent that the two markets do not fluctuate consistently, hedge ineffectiveness will result. The Company's designation would be as follows:

Date of Designation—January 1, 2000.

Hedge Instrument—NYMEX long futures contract for 100 troy ounces at $300/troy ounce for June 2000 delivery.

Hedged Item—Firm commitment to deliver 100 troy ounces of gold in London at a price of $310/troy ounce on June 30, 2000.

Strategy and Nature of Risk Being Hedged—Changes in the fair value of the gold futures contract should substantially offset changes in the fair value of the firm commitment caused by changes in the London spot price of gold.

How Hedge Effectiveness Will Be Assessed—The use of a six-month NYMEX futures contract to hedge against changes in the London spot price would have been highly effective over the last six months of 1999 as the London spot price has increased $50, while the New York futures price also increased $50.[377] Going forward, the difference between the change in the London spot price, as determined by reference to the quoted price in The Wall Street Journal for the London Fixing Spot and the change in the June NYMEX futures price will be used to measure ineffectiveness. The hedge meets the criteria of a fair value hedge of a firm commitment-the sales contract.

At March 31, 2000, the London spot price is $350 and the June NYMEX futures price is $345. The fair value of the futures contract is $4,500 ($45 increase in NYMEX futures price ∞ 100 ounces). However, the firm commitment has decreased in value because the London spot price has risen $40/troy ounce, causing an unrealized loss of $4,000. Through the first quarter of 2001, the Company would have made entries (ignoring margin requirements) totaling the following:

To recognize change in the fair value of futures contract.

To recognize the change in the fair value of the firm contract to sell gold at a price of $310 when the current price is $350/troy ounce.

The hedge ineffectiveness can be calculated as follows:

If there were no further changes in the London spot price or NYMEX futures price, the entries would unwind on June 30 as follows:

To recognize sale of gold contracted at $310/troy ounce but hedged to spot price of $350/troy ounce.

At the conclusion of the transaction and after the effect of the hedge, the Company has effectively sold the gold at the June spot price even though the contract was at a price fixed in January and recognized a $500 gain from the ineffectiveness caused by using the change in the NYMEX futures to hedge the change in London spot prices. The change in fair value of sales contract that occurred ($4,000) is recognized in sales because it is considered part of the hedged transaction, the sale of gold. The $500 is recorded in other income, not sales, because this portion of the change in value of the derivative does not qualify for the special hedge accounting.

Cash flow hedges protect against the risk caused by variable prices, costs, rates, or terms that cause future cash flows to be uncertain. A cash flow hedge is a hedge of an anticipated or forecasted transaction that is probable of occurring in the future, but the amount of the transaction has not been fixed. In some circumstances, the anticipated or forecasted transaction is related to a contractual requirement (e.g., percentage of sales royalty arrangement payable in a foreign currency) or an existing balance (e.g., variable rate term debt). This contrasts with fair value hedges that protect against the risk created by fixed prices, costs, rates, or terms (e.g., contracted quantities and prices, fixed rate debt).

A typical example of a cash flow hedge would be the expected purchase of Swiss watches by a U.S. importer. Prior to signing any firm contracts, the importer's budget reflects the purchase of 12,000 watches spread ratably over the next calendar year. The importer typically pays for its Swiss watch purchases in Swiss francs. At the current spot exchange rate, the anticipated purchases over the next year will cost $12 million. The company, concerned that the Swiss franc may appreciate over the next year compared to the dollar, enters into a series of foreign currency forward contracts to buy Swiss francs each month over the next year at today's forward exchange rate. If the Swiss franc strengthens compared to the dollar, the importer will pay more, in dollar terms, for the watches; however, gains on the forward contracts will offset the higher purchase prices. If the Swiss franc weakens, the Company will pay less for the watches, but will incur losses on the forwards. In either case, provided the 12,000 watches are purchased, the exchange rate on the $12,000,000 has been effectively fixed. In this example, the price (both in U.S. dollar and Swiss franc terms) and the exchange rate are variable, and the purchases represent forecasted transactions. Thus, the importer could classify the forward contracts as a cash flow hedge.

Forecasted transactions are eligible for cash flow hedge accounting, while firm commitments are eligible for fair value hedge accounting. Forecasted transactions are broadly defined as probable future transactions that do not meet the definition of a firm commitment. They can be contractually established or merely probable because of a company's past or expected business practices. As discussed previously, to meet the definition of a firm commitment, all of the relevant terms must be fixed (e.g., price, quantity, timing, interest rate). To qualify as a forecasted transaction, some element of the transaction (other than the currency) must be variable. Therefore, the distinguishing characteristic between a forecasted transaction and a firm commitment is the certainty and enforceability of the terms of the transaction. Using the example above, the purchase of the watches would change from a forecasted transaction to a firm commitment if the importer contracts with a Swiss vendor for a specified quantity of watches at a specified price at a specified date.

Examples of forecasted transactions include:

Issuance of long-term debt three months from now (i.e., the interest rate is not known)

Budgeted sales of products at market terms for the upcoming year

Royalty or license payments denominated in a foreign currency based on future sales volume

Contracts requiring delivery of specified quantities of a commodity at market (variable) prices in the future

Expected interest obligations on renewal of short-term commercial paper obligations

Contractually required interest payments on a floating rate long-term borrowing arrangement

Variable rate cash flows from a long-term investment

In each of the above cases, the amount of cash to be paid or received is variable, and hedging could be used to lock in the amount.

A firm commitment that is denominated in a foreign currency can be treated as either a fair value exposure or a cash flow exposure under Statement No. 133. The designation determines whether the effects of the hedge will be recognized in income or in equity. For example, if a company contracts to buy a piece of machinery at a specified date and price denominated in a foreign currency, the terms of the purchase are fixed and represent a firm commitment. However, the exchange rate is not fixed and represents a variable exposure. Accordingly, the Statement permits the hedge to be structured as either a fair value hedge or a cash flow hedge.

Sometimes the same derivative can be paired up with a forecasted transaction in a cash flow hedge and then redesignated as a fair value hedge if the forecasted transaction later becomes a firm commitment. Consider a U.S. company that on January 1 anticipates an inventory purchase denominated in a foreign currency on July 1. The U.S. company enters into a foreign currency forward maturing on July 1 and initially designates the forward as a cash flow hedge of the anticipated purchase. On May 1, the company contracts with a vendor for the purchase, and the contract represents a firm commitment. At that time, the company chooses to redesignate the derivative as a fair value hedge. Gains or losses on the forward from January 1 to April 30 would remain in other comprehensive income, while gains or losses from May 1 to July 1 would be recognized in earnings, offsetting remeasurement gains or losses on the firm commitment. On July 1, when the purchase is complete, the firm commitment balance becomes part of the basis of the inventory and the forward transaction is closed out. When the inventory is sold in August, the company recognizes the gains and losses deferred in other comprehensive income in earnings. The firm commitment balance that became part of the basis in the inventory also is recognized in cost of sales. ("The Accounting Treatment for Cash Flow Hedges" section below provides further insight and background into this treatment.)

To qualify for the "special accounting" applicable to cash flow hedges, both the derivative and the hedged cash flows must meet the general criteria previously discussed as well as certain criteria specific to cash flow hedges. The specific criteria are:

The forecasted transaction being hedged must be explicitly preidentified and formally documented with sufficient specificity so that when a transaction occurs, it is clear whether that transaction is or is not the hedged transaction. The nature of the asset or liability involved and the expected currency amount or quantity of the forecasted transaction must be specified.

The forecasted transaction must be probable of occurring.

Except for forecasted intercompany transactions denominated in a foreign currency, the forecasted transaction must be a transaction with a third party, external to the reporting entity. (Forecasted foreign currency transactions with affiliates may be accounted for as cash flow hedges—see below.)

In addition, Statement No. 133 contains special provisions for basis swaps. Basis swaps are most commonly interest rate swaps that require the exchange of one variable rate of interest for another. They are used by entities that seek to modify variable cash flows from one variable index (e.g., bank debt tied to the prime rate) to another variable index (e.g., LIBOR). The Statement only permits basis swaps to be accounted for as hedges when they are designated as hedges at inception and an entity has assets with one variable rate to which one leg of the swap can be linked and liabilities with the other variable rate to which the other leg of the swap can be linked. For example, an entity with variable rate debt tied to changes in the prime rate can use a swap to modify the interest payments to a six-month LIBOR base only if the entity also owns investments with interest income tied to the six-month LIBOR rate. As a result of this provision, commercial companies that borrow from a bank at the prime rate may not be able to use a basis swap to convert the interest characteristics of the debt to a more variable rate, such as LIBOR, and treat the swap as a hedge for financial reporting purposes.

Derivatives designated as hedges of forecasted transactions are carried at fair value with the effective portion of a derivative's gain or loss recorded in other comprehensive income (i.e., a separate component of shareholders' equity) and subsequently recognized in earnings in the same period or periods the hedged forecasted transaction affects earnings.[378] The change in the present value of the expected future cash flows (which represents the fair value) of the hedged transaction is not recognized in the financial statements. For example, a hedge of the commodity price risk of anticipated inventory purchases is marked to market through comprehensive income and subsequently recognized in income at the date the inventory is sold rather than the inventory purchase date. Similarly, the gain/loss of a cash flow hedge related to a fixed asset purchase, initially deferred in other comprehensive income, is maintained in other comprehensive income and amortized as an adjustment to depreciation expense over the depreciable life of the fixed asset.

As with all hedges, the hedge must be highly effective to even qualify as a hedge under the Statement's criteria. However, after qualifying as a cash flow hedge, the treatment of hedge ineffectiveness is more complicated compared to a fair value hedge where both the derivative and the hedged item are marked to market (with respect to the hedged risk) through earnings. The cash flow model essentially records any overeffectiveness (i.e., overhedge) in earnings, while not permitting any recognition of an undereffective (i.e., underhedge) portion of a hedge. For cash flow hedges under Statement No. 133, accumulated other comprehensive income associated with the hedged transaction shall at all times reflect the lesser of the following:

The cumulative gain or loss on the derivative from the inception of the hedge (less any component of the derivative excluded from the effectiveness assessment and any amount previously reclassified from other comprehensive income to earnings)

The portion of the cumulative gain or loss on the derivative necessary to offset the cumulative change in expected future cash flows on the hedged transaction from inception of the hedge (less the derivative's gains or losses previously reclassified from accumulated other comprehensive income to earnings)

Keeping in mind that the derivative must always be carried at fair value, any difference between the change in fair value of the derivative and the amount that may be recorded in other comprehensive income must be recorded in earnings as the ineffective element of the hedge (i.e., the cumulative "mismatch").

To illustrate, if a derivative changes in fair value by $10, but the present value of expected cash flows of the hedged transaction only changes by an offsetting $8, there is $2 of hedge ineffectiveness included in the change in fair value of the derivative. Thus, the entry to other comprehensive income is limited to $8 with the $2 difference immediately recognized in earnings. If, instead, the present value of expected cash flows of the hedged transaction changes by $12, the adjustment to comprehensive income is $10 because the entire change in the value of the derivative is effective. In the latter case, no entry is required for the $2 difference.

This provision is further complicated by the fact that the comparison is on the cumulative change in the value of the derivative and the present value of the expected cash flows, requiring that cumulative calculations be made throughout the life of the hedge. As stated above, if at the end of one month the fair value of the derivative has changed by $10, but the present value of the expected cash flows of the hedged transaction have only changed by an offsetting $8, the adjustment to other comprehensive income is limited to $8. If at the end of the next month, the fair value of the derivative has increased to $15, or an additional $5, and the offsetting present value of the expected cash flows has changed to $15 (an additional $7), then the entire $15 is included in other comprehensive income and the $2 difference from the previous month is "caught up" in the current month, resulting in $2 being reversed through income.

As previously discussed, firm commitments and forecasted transactions are similar in that they both represent probable future transactions. Thus, the differences in the treatment of hedge ineffectiveness for cash flow hedges and fair value hedges are significant. For instance, in the previous example, when the present value of expected cash flows of an anticipated transaction changed by $12, but the derivative only offsets the change by $10, only the $10 was recognized in other comprehensive income and no entry was recognized for the $2 difference. However, had the forecasted transaction been a firm commitment, the entire change in fair value of the derivative ($10) and the change in fair value of the firm commitment attributable to the risk being hedged ($12) would have been recognized in income, thereby impacting income by $2.

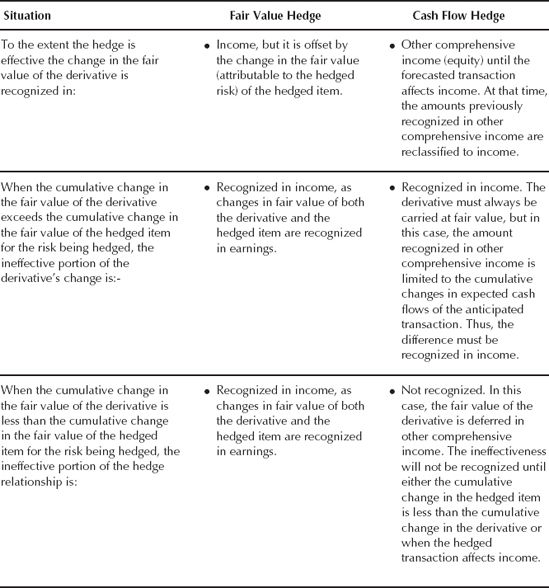

Exhibit 26.1 highlights the significant differences between the treatment of fair value and cash flow hedges.

If the hedged item is denominated in a foreign currency, an entity may designate a cash flow hedge of the foreign currency exposure of the following:

A forecasted transaction with either an external party (i.e., an export sale to an unaffiliated foreign entity) or an intercompany party (i.e., a sale to a foreign subsidiary or a forecasted royalty from a foreign subsidiary)

An unrecognized firm commitment (because even though the price is fixed, the ultimate cash flow varies based on foreign exchange rate movements)

The forecasted functional currency-equivalent cash flows associated with a recognized asset or liability.

In most cases, the entity with the foreign currency exposure must be a party to the hedging instrument.