Michael J. Ramos

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 made significant changes to many aspects of the financial reporting process. One of those changes is a requirement that management evaluate the effectiveness of its internal control over financial reporting and provide a report on this evaluation. Additionally, the company's independent auditors are required to audit this internal control report in conjunction with their traditional audit of the company's financial statements.

This chapter summarizes management's evaluation and reporting requirements and provides a structured, comprehensive approach for compliance. The material in this chapter has been excerpted from How to Comply with Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404: Assessing the Effectiveness of Internal Control, by Michael Ramos, published by John Wiley & Sons.

For the purposes of complying with the internal control reporting requirements of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the SEC rules provide the working definition of the term internal control over financial reporting. Rule 13a-15(f) defines internal control over financial reporting as follows:

The term internal control over financial reporting is defined as a process designed by, or under the supervision of, the issuer's principal executive and principal financial officers, or persons performing similar functions, and effected by the issuer's board of directors, management and other personnel, to provide reasonable assurance regarding the reliability of financial reporting and the preparation of financial statements for external purposes in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles and includes those policies and procedures that:

Pertain to the maintenance of records that in reasonable detail accurately and fairly reflect the transactions and dispositions of the assets of the issuer;

Provide reasonable assurance that transactions are recorded as necessary to permit preparation of financial statements in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles, and that receipts and expenditures of the issuer are being made only in accordance with authorizations of management and directors of the issuer; and

Provide reasonable assurance regarding prevention or timely detection of unauthorized acquisition, use or disposition of the issuer's assets that could have a material effect on the financial statements.

When considering the SEC's definition, you should note the following:

The term internal control is a broad concept that extends to all areas of the management of an enterprise. The SEC definition narrows the scope of an entity's consideration of internal control to the preparation of the financial statements—hence the use of the term internal control over financial reporting.

The SEC intends its definition to be consistent with the definition of internal controls that pertain to financial reporting objectives that was provided in the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) of the Treadway Commission COSO Report.

The rule makes explicit reference to the use or disposition of the entity's assets—that is, the safeguarding of assets.

Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act requires chief executive officers (CEOs) and chief financial officers (CFOs) to evaluate and report on the effectiveness of the entity's internal control over financial reporting. This report is contained in the company's Form 10K, which is filed annually with the SEC. The SEC has adopted rules for its registrants that effectively implement the requirements of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, Section 404.

Under the SEC rules, the company's 10K must include:[172]

Management's Annual Report on Internal Control Over Financial Reporting. Provide a report on the company's internal control over financial reporting that contains:

A statement of management's responsibilities for establishing and maintaining adequate internal control over financial reporting.

A statement identifying the framework used by management to evaluate the effectiveness of the company's internal control over financial reporting.

Management's assessment of the effectiveness of the company;s internal control over financial reporting as of the end of the most recent fiscal year, including a statement as to whether or not internal control over financial reporting is effective. This discussion must include disclosure of any material weakness in the company's internal control over financial reporting identified by management. Management is not permitted to conclude that the registrant's internal control over financial reporting is effective if there are one or more material weaknesses in the company's internal control over financial reporting.

A statement that the registered public accounting firm that audited the financial statements included in the annual report has issued an attestation report on management's assessment of the registrant's internal control over financial reporting.

Attestation Report of the Registered Public Accounting Firm. Provide the registered public accounting firm's attestation report on management's assessment of the company's internal control over financial reporting.

Changes in Internal Control Over Financial Reporting. Disclose any change in the company's internal control over financial reporting that has materially affected, or is reasonably likely to materially affect, the company's internal control over financial reporting.

The company's annual report filed with the SEC also should include management's fourth-quarter report on the effectiveness of the entity's disclosure controls and procedures, as described in the next section.

The requirement to disclose material changes in the entity's internal control (item (c) above) became effective on August 14, 2003. The effective date for the other provisions of the rules described above—that is, management's report on the effectiveness of internal control and the related auditor attestation—become effective at different times, depending on the filing status of the company.

Accelerated filer. A company that is an accelerated filer as of the end of its first fiscal year ending on or after November 15, 2004, must begin to comply with the internal control reporting and attestation requirements in its annual report for that fiscal year.[173]

Nonaccelerated filer. Smaller companies are required to comply with the full requirements of the new rules for their first fiscal year ending on or after July 15, 2007.

Foreign private issuers. The effective data for foreign private issuers depends on whether the issuer is an accelerated or non-accelerated filer. Accelerated filers are required to comply for their first fiscal year ending on or after July 15, 2006. Non-accelerated foreign private issuers have until July 15, 2007.

Section 302 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act requires quarterly reporting on the effectiveness of an entity's "disclosure controls and procedures." Item 307 of SEC Regulation S-K implements this requirement for the company's quarterly Form 10-Q filings by requiring management to:

Disclose the conclusions of the company's principal executive and principal financial officers, or persons performing similar functions, regarding the effectiveness of the company's disclosure controls and procedures as of the end of the period covered by the report, based on the evaluation of these controls and procedures.

In addition to reporting on disclosure controls, the company's quarterly reports also must disclose material changes in the entity's internal control over financial reporting.

Note that for these quarterly filings:

Management is not required to evaluate or report on internal control over financial reporting. That evaluation is required on an annual basis only.

The company's independent auditors are not required to attest to management's evaluation of disclosure controls.

With these rules, the SEC introduces a new term, disclosure controls and procedures, which is different from internal controls over financial reporting defined earlier. SEC Rule 13a-15(e) defines disclosure controls and procedures as those that are:

Designed to ensure that information required to be disclosed by the issuer in the reports that it files or submits under the Act is

recorded,

processed,

summarized, and

reported

within the time periods specified in the Commission's rules and forms. Disclosure controls and procedures include, without limitation, controls and procedures designed to ensure that information required to be disclosed by an issuer in the reports that it files or submits under the Act is accumulated and communicated to the issuer's management, including its principal executive and principal financial officers, or persons performing similar functions, as appropriate to allow timely decisions regarding required disclosure [emphasis added].

Thus, "disclosure controls and procedures" would encompass the controls over all material financial and nonfinancial information in Exchange Act reports. Information that would fall under this definition that would not be part of an entity's internal control over financial reporting might include the signing of a significant contract, changes in a strategic relationship, management compensation, or legal proceedings.

In relation to its rule requiring an assessment of disclosure controls and procedures, the SEC also advised all public companies to create a disclosure committee to oversee the process by which disclosures are created and reviewed, including the:

Review of 10-Q, 10K, and other SEC filings; earnings releases; and other public information for the appropriateness of disclosure

Determination of what constitutes a significant transaction or event that requires disclosure

Determination and identification of significant deficiencies and material weaknesses in the design or operating effectiveness of disclosure controls and procedures

Assessment of CEO and CFO awareness of material information that could affect disclosure

The existence and effective operation of an entity's disclosure committee can have a significant effect on the nature and scope of management's work to evaluate the effectiveness of the entity's internal control. For example:

The effective functioning of a disclosure committee may be viewed as an element that strengthens the entity's control environment.

The work of the disclosure committee may create documentation that engagement teams can use to reduce the scope of their work.

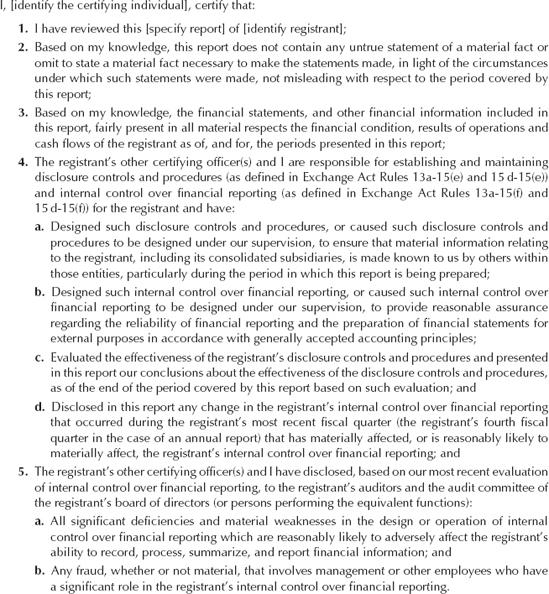

In addition to providing a report on the effectiveness of its disclosure controls and internal control over financial reporting, the company's principal executive officer and principal financial officer are required to sign two certifications, which are included as exhibits to the entity's 10-Q and 10K. These two certifications are required by the following sections of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act:

Section 302, which requires a certification to accompany each quarterly and annual report filed with the SEC

Section 906, which added a new Section 1350 to Title 18 of the U.S. Code, and which contains a certification requirement subject to specific federal criminal provisions. This certification is separate and distinct from the Section 302 certification requirement.

Exhibit 4.1 provides the text of the Section 302 certification. This text is provided in SEC Rule 13a-14(a) and should be used exactly as set forth in the rule.

Exhibit 4.2 provides an example of the Section 906 certification. Note that some certifying officers may choose to include a "knowledge qualification," as indicated by the optional language within the parentheses. Officers who choose to include this language should do so only after consulting with their SEC counsel. Unlike the Section 302 certification, which requires a separate certification for both the CEO and CFO, the company can provide only one 906 certification, which is then signed by both individuals.

A great deal of the information included in financial statements and other reports filed with the SEC originates in areas of the company that are outside the direct control of the CEO and CFO. Because of the significance of information prepared by others, it is becoming common for the CEO and CFO to request those individuals who are directly responsible for this information to certify it. This process is known as subcertification, and it usually requires the individuals to provide a written affidavit to the CEO and CFO that will allow them to sign their certifications in good faith.

Items that may be the subject of subcertification affidavits include:

Adequacy of specific disclosures in the financial statements or other reports filed with the SEC, such as Management's Disclosure and Analysis included in the entity's 10Q or 10K.

Accuracy of specific account balances.

Compliance with company policies and procedures, including the company's code of conduct.

Adequacy of the design and/or operating effectiveness of departmental internal controls and disclosure controls.

Accuracy of reported financial results of the department, subsidiary, or business segment.

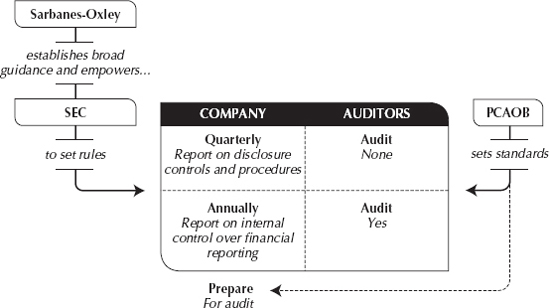

Exhibit 4.3 describes the relationship between the various rule-making bodies, companies, and their auditors regarding the reporting on internal control. As described previously, management of public companies is required to report on the effectiveness of the entity's internal control on an annual basis and the company's independent auditors are required to audit this report. The SEC is responsible for setting rules to implement the Sarbanes-Oxley Act requirements. Those rules include guidance for reporting by the CEO and CFO on the entity's internal control over financial reporting and disclosure controls, but they do not provide any guidance or set standards for the independent auditors. The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) sets the auditing standards, which have a direct effect on auditors and how they plan and perform their engagements.

In addition, the auditing standards will have an indirect effect on the company as it prepares for the audit of the internal control report. Just as in a financial statement audit, the company should be able to support its conclusions about internal control and provide documentation that is sufficient for the auditor to perform an audit. Thus, in preparing for the audit of its internal control report, it is vital for management, and those who assist them, to have a good understanding of what the independent auditors will require. In practice, the auditing standards, and related interpretative guidance, have become the de facto definitive guidance for both management and auditors on the assessment of internal control effectiveness.

In June 2004, the SEC approved PCAOB Auditing Standard No. 2, An Audit of Internal Control Over Financial Reporting Performed in Conjunction With an Audit of Financial Statements. This standard requires auditors for the first time to conduct two audits of their publicly traded clients: the traditional audit of financial statements and a new audit of internal control. The standard provides definitive guidance for independent auditors on the performance of their audit of internal control.

The Auditing Standard has a significant effect on the way in which company management conducts its own required assessment in internal control effectiveness. For example, the standard:

Requires auditors to assess the quality of the company's self-assessment of internal control. In providing this guidance, the standard describes certain required elements of management's process that must be present for the auditor to conclude that the process was adequate.

Requires auditors to assess the adequacy of the company's documentation of internal control. The standard goes on to provide definitive guidance on what management's documentation should contain for the auditor to conclude that it is adequate. Lack of adequate documentation is considered a control deficiency that may preclude an unqualified opinion on internal control or may result in a scope limitation on the auditor's engagement.

Allows the auditor to rely on the work performed by the company in its self-assessment process to support his or her conclusion on internal control effectiveness. However, to rely on this work to the maximum extent, certain conditions regarding the nature of the work and the people who performed it must be met.

Establishes the definition of a material weakness in internal control. To conclude that internal control is effective, management should have reasonable assurance that there were no material weaknesses in internal control as of the reporting date.

Subsequent to the approval of the Auditing Standard, both the PCAOB and the SEC have released periodically documents of answers to frequently asked questions. These documents set forth the PCAOB and SEC staff's opinions and views on certain matters. Although both the PCAOB and the SEC both point out that these opinions and views do not represent official "rules," you should be prepared to justify any departure from the answers to questions discussed in these documents. An important step in planning a SOX 404 compliance engagement is to make sure you have read the most current staff positions issued by the PCAOB and the SEC

The auditor's objective in an audit of internal control is to express an opinion about management's assessment of the effectiveness of the company's internal control over financial reporting. This objective implies a two-step process.

First, management must perform its own assessment and conclude on the effectiveness of the entity's internal controls.

Next, the auditors will perform their own assessment and form an independent opinion as to whether management's assessment of the effectiveness of internal control is fairly stated.

Thus, internal control is assessed twice, first by management and then by the independent auditors. That the auditors will be auditing internal control—and in some cases, reperforming some of the tests performed by the entity—does not relieve management of its obligation to document, test, and report on internal control.

To form his or her opinion, the auditor will:

Evaluate the reliability of the process used by management to assess the entity's internal control

Review and rely on the results of some of the tests performed by management, internal auditors, and others during their assessment process

Perform his or her own tests

The SEC rules relating to the scope of managements assessment of internal control effectiveness are rather general. In practice, companies frequently encounter situations for which the SEC has not provided guidance. In those situations, companies will commonly look to the Auditing Standard to help determine which business units or controls should be included in their assessment.

AS No. 2 provides extensive guidance on the required scope of management's self-assessment of the company's internal control. This guidance is in the context of the external auditor's evaluation of the quality of the company's assessment process, stating that the external auditor should determine whether management's evaluation includes certain elements.

If the company's self-assessment process does not include all the elements listed in the standard, the external auditor will conclude that the process was inadequate, in which case he or she will be forced to determine that a scope limitation had been placed on the engagement and modify the "clean opinion" on internal control. As a practical matter, most companies take steps to ensure that their assessment process includes all the required elements listed in the auditing standard.

The auditing standard provides detailed guidance on what is required of management's process, stating that management should address the following elements.

Determining which controls should be tested, including controls over all relevant assertions related to all significant accounts and disclosures in the financial statements. Generally, such controls include:

Controls over initiating, authorizing, recording, processing, and reporting significant accounts and disclosures and related assertions embodied in the financial statements.

Controls over the selection and application of accounting policies that are in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles.

Antifraud programs and controls.

Controls, including information technology general controls, or which other controls are dependent.

Controls over significant nonroutine and nonsystematic transactions, such as accounts involving judgments and estimates.

Company level controls (as described in paragraph 53), including:

The control environment, and

Controls over the period-end financial reporting process, including controls over procedures used to enter transaction totals into the general later, to initiate, authorize, record, and process journal entries in the general ledger; and to record recurring and nonrecurring adjustments to the financial statements (e.g., consolidating adjustments, report combinations, and reclassifications).

Evaluating the likelihood that failure of the control could result in a misstatement, the magnitude of such a misstatement, and the degree to which other controls, if effective, achieve the same control objectives.

Determining the locations or business units to include in the evaluation for a company with multiple locations or business units (See paragraphs B1 through B17).

Evaluating the design effectiveness of controls.

Evaluating the operating effectiveness of controls based on procedures sufficient to assess their operating effectiveness. Examples of such procedures include testing of the controls by internal audit, testing of controls by others under the direction of management, using a service organization's reports (see paragraphs B18 through B29), inspection of evidence of the application of controls, or testing by means of a self-assessment process, some of which might occur as part of management's ongoing monitoring activities. Inquiry alone is not adequate to complete this evaluation. To evaluate the effectiveness of the company's internal control over financial reporting, management must have evaluated controls over all relevant assertions related to all significant accounts and disclosures.

Determining the deficiencies in internal control over financial reporting that are of such a magnitude and likelihood of occurrence that they constitute significant deficiencies or material weaknesses.

Communicating findings to the external auditor and to others, if applicable.

Evaluating whether findings the reasonable and support management's assessment.

How to Comply with Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404: Assessing the Effectiveness of Internal Control provides detailed guidance to help you comply with each of these required elements of management's assessment process. The Sarbanes-Oxley 404 Implementation Toolkit provides an integrated set of forms, checklists, example questions, and other practice aids to help you perform an assessment of internal control.

The external auditors are required to evaluate the adequacy of management's documentation of internal control. Again, the consequences of not complying with the requirements of the Auditing Standard are severe.

Paragraph 42 of the standard provides the requirements for the documentation of internal control. That paragraph requires management's documentation to include the following.

The design of controls over all relevant assertions related to all significant accounts and disclosures in the financial statements. The documentation should include the five components of internal control over financial reporting as discussed in paragraph 49, including the control environment and company-level controls as described in paragraph 53;

Information about how significant transactions are initiated, authorized, recorded, processed, and reported;

Sufficient information about the flow of transactions to identify the points at which material misstatements due to error or fraud could occur;

Controls designed to prevent or detect fraud, including who performs the controls and the related segregation of duties;

Controls over the period-end financial reporting process;

Controls over safeguarding of assets (See paragraphs C1 through C6); and

The results of management's testing and evaluation.

The auditing standard also provides guidance on the nature, timing, and extent of the auditor's procedures for a number of situations, including:

Extent of testing of multiple locations, business segments, or subsidiaries

Required tests when the entity uses a service organization to process transactions

Updated test work required when the original testing was performed at an interim date in advance of the reporting date

Interpretative guidance issued by the staffs of the SEC and PCAOB provide information on how to address additional situations that may raise questions about the scope of the work.

Both Sarbanes-Oxley and the PCAOB Auditing Standard describe a two-pronged approach for providing financial statement users with useful information about the reliability of a company's internal control:

First, management assesses and reports on the effectiveness of the entity's internal control.

Second, the company's external auditors audit management's report and issue a separate, independent opinion on the effectiveness of the company's internal control.

In this scheme, it is vital that the two participants perform their duties independently of each other.

By the same token, the practical aspects of implementing the requirements of Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404 suggest that external auditors should be able to use, to some degree, the work performed by management in its self-assessment of internal control in their audit. To do otherwise, to completely prohibit external auditors form using some of management's work, would make the cost of compliance quite steep.

Thus, the Auditing Standard balances two competing goals: objectivity and independence of the parties involved versus the use of management's work by the external auditor as a means of limiting the overall cost of compliance.

Note: The company is prohibited in its self-assessment of internal control from relying on the work performed by the external auditors in their audit.

Keep in mind that the company is required to perform a thorough, detailed assessment of the company's internal control. As much as possible, management will want to provide the results of its work to the external auditors, so the auditors will not have to duplicate the company's efforts.

Paragraphs 108 through 126 of the Auditing Standard provide extensive guidance on the degree to which the company's work on internal control can be used by the external auditors. The relevant section is titled "Using the Work of Others" The standard indicates that the work of "others" includes the relevant work performed by:

Internal auditors.

Other company personnel.

Third parties working under the direction of management or the audit committee.

The external auditor's ability to rely on the work of others has its limits. Paragraph 108 of the standard describes the fundamental principle in the external auditor's using the work of others. The external auditor must "perform enough of the testing himself or herself so that the external auditor's own work provides the principal evidence for the external auditor's opinion." The standard goes on to describe a framework for ensuring that the external auditors comply with this principle. Essentially:

The external auditor is prohibited from using the company's work in certain areas of the audit.

For all other areas, the external auditor may use the company's work, if certain conditions are met.

There are two areas where the external auditors are prohibited from using the company's work in their audit.

Control environment. The external auditors are prohibited from using the work of company management and others to reduce the amount of work they perform on controls in the control environment. This does not mean that they can ignore your work in this area. To the contrary, paragraph 113 of the standard requires the external auditor to "consider the results of worked performed in this area by others because it might indicate the need for the external auditor to increase his or her own work."

Walkthroughs. External auditors are required to perform at least one walkthrough for each major class of transactions. A walkthrough involves tracing a transaction from origination through the company's information systems until it is reflected in the company's financial reports. Chapter 3 of this Practice Aid discusses the requirements for walkthroughs in more detail.

Note that paragraph 115 of the standard states that "controls specifically established to prevent and detect fraud" are part of the control environment. Thus, the external auditors will be testing antifraud programs and controls themselves.

For all areas other than the control environment and the walkthroughs, the external auditors may use the company's tests on internal control during their audit. Paragraph 109 of the standard summarizes the steps that the external auditor's must follow to use the work of others to support his or her conclusions reached in the audit of internal control. To determine the extent to which the external auditor may use of company's work, the external auditor is required to:

Evaluate the nature of the controls subjected to the work of others. In general, auditors will probably want to perform their own tests on the controls related to accounts that have a high risk of material misstatement. For the controls for less risky accounts they will be more inclined to rely on the work of the company.

The more competent and objective the company's project team, the more likely the external auditors will be to rely on their work.

Test some of the work performed by others to evaluate the quality and effectiveness of their work.

To allow the company's external auditors to make as much use as possible of the company's own assessment of internal control, company management should have a clear understanding of the conditions that must be met for the external auditor's to use the work. To help the external auditors determine that those criteria have been met, you may wish to document your compliance with the key requirements of the auditing standard and make this documentation available to the external auditors early on in their audit planning process. For example, you should consider:

Obtaining the bios or resumes of project team members showing their education level, experience, professional certification, and continuing education.

Documenting the company's policies regarding the assignments of individuals to work areas.

Documenting the "organizational status" of the project team and how they have been provided access to the board of directors and audit committee.

Determining that the internal auditors follow the relevant internal auditing standards.

Establishing policies that ensure that the documentation of the work performed includes:

A description of the scope of the work

Work programs

Evidence of supervision and review

Conclusions about the work performed

The SEC reporting rules require entity management to disclose material weaknesses in internal control. Engagements to assess the effectiveness of internal controls should be planned and performed in a way that will detect material misstatements. Thus, it is critical that you have a working definition of the term. The auditing standard provides the following definitions.

A control deficiency exists when the design or operation of a control does not allow management or employees, in the normal course of performing their assigned functions, to prevent or detect misstatements on a timely basis.

A significant deficiency is a control deficiency, or combination of control deficiencies, that adversely affects the company's ability to initiate, authorize, record, process, or report external financial data reliably in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles such that there is more than a remote likelihood that a misstatement of the company's annual or interim financial statements that is more than inconsequential will not be prevented or detected. Note: A misstatement is inconsequential if a reasonable person would conclude, after considering the possibility of further undetected misstatements, that the misstatement, either individually or when aggregated with other misstatements, would clearly be immaterial to the financial statements. If a reasonable person could not reach such a conclusion regarding a particular misstatement, that misstatement is more than inconsequential.

A material weakness is a significant deficiency, or combination of significant deficiencies, that results in more than a remote likelihood that a material misstatement of the annual or interim financial statements will not be prevented or detected.

To render an opinion on either the financial statements or the effectiveness of internal control, the company's independent auditors are required to maintain their independence, in accordance with applicable SEC rules. These rules are guided by certain underlying principles, which include:

The audit firm must not be in a position where it audits its own work.

The auditor must not act as management or as an employee of the client.

The PCAOB Auditing Standard incorporates the SEC's principles in its auditing standard and then expands on these principles in important ways. Although maintaining independence is primarily the responsibility of the auditors several of the independence requirements of AS No. 2 impose certain responsibilities on management and the audit committee. These requirements include:

Preapproval by the audit committee. Each internal control-related service to be provided by the auditor must be preapproved by the audit committee. In its introduction to the standard, the PCAOB clarifies that "the audit committee cannot pre-approve internal control-related services as a category, but must approve each service."

For proxy or other disclosure purposes, the company may designate some auditor services as "audit" or "nonaudit" services. The requirement to preapprove internal control services applies to any internal control-related services, regardless of how they might be designated.

Active involvement of management. Management must be "actively involved" in a "substantive and extensive" way in all internal control services the auditor provides. Management can not delegate these responsibilities, nor can it satisfy the requirement to be actively involved by merely accepting responsibility for documentation and testing performed by the auditors.

Independence in fact and appearance. The company's audit committee and external auditors must be diligent to ensure that independence both in fact and appearance is maintained.

No matter how detailed the independence rules may become, they can not possibly address every possible interaction between the company and its auditors. During the initial implementation of SOX 404 many situations arose that called into question whether the auditor could interact with the company in a particular way and still maintain its independence.

For example, if the company was unsure whether it's documentation of internal control would be acceptable, could it approach its auditors for advice? If the auditors made recommendations on how to improve the documentation and the company then incorporated those recommendations, wouldn't that put the audit firm in the position of auditing its own work when it reviewed that documentation? The form and content of the company's documentation of its internal control is the responsibility of management. If the auditor becomes significantly involved in that decision, doesn't that imply that they are acting in the capacity of management?

In the initial implementation of SOX 404, it became common for auditors provide as little advice as possible to their clients on internal control matters. Concerned about possibly violating the independence rules they chose to largely remove themselves from their client's efforts.

As a practical matter, both the SEC and the PCAOB understood that the public interest is not well-served if the independent auditors are completely uninvolved from the company's efforts to understand and assess its internal control. There must be some sharing of information between the company and its auditors, and the auditors must be able to provide help and advice on some matters.

In June of 2004 the SEC and PCAOB issued some guidance in this area. Essentially that guidance allows the auditor to provide "limited assistance to management in documenting internal controls and making recommendations for changes to internal controls. However, management has the ultimate responsibility for the assessment, documentation and testing of the company's internal control."

The PCAOB provided more extensive guidance on how company management may solicit advice from and share advice with their auditors on internal control matters. The guidance from the staff was in answer to a question directed specifically to an auditor's review of the company's draft financial statements or their providing advice on the adoption of a new accounting principle or emerging issue—services that historically have been considered a routine part of a high quality audit.

The PCAOB staff stated that, "some type of information-sharing on a timely basis between management and the auditor is necessary." However, when management seeks the assistance of the company's auditors to help with its internal control assessment, it should make it clear that management retains the ultimate responsibility for internal control. The PCAOB places the burden on management to clearly communicate with the auditors the nature of the advice they are seeking and the purpose for which the auditor is being involved.

As indicated previously, both the SEC and PCAOB periodically issue staff position papers to clarify how AS 2 applies in specific circumstances. On May 16, 2005, in response information that was gathered about the first year of implementation, both the SEC and PCAOB issued guidance that addressed the most significant problems encountered with the implementation of AS 2. Of the five main areas addressed in the guidance, the following are the most relevant to company management.

Use a risk-based, top-down approach. The PCAOB emphasized that auditors should use a top-downapproach, and company management would be wise to use this same approach. In a top-down approach, you begin with an evaluation of entity-level controls and from there move to the testing of detailed activity-level controls.

One of the key principles of the top-down approach is that the decision of which controls to document and test is based an assessment of risk. Controls that mitigate significant risks should be documented and assessed. Those that mitigate less significant risks would be subject to considerably less, if any testing and evaluation.

The risk-based, top-down approach is described in more detail in the next section of this chapter.

Auditors and company management should engage in direct and timely communication with each other. As described in the previous section of this chapter, during the first year of compliance, there was often a lack of communication between the two. With its May 16 guidance, the PCAOB makes it clear that auditor should be responsive to client requests for advice, provided that company management take final responsibility for internal control.

Auditors should make as much use as possible of the work on internal control performed by the company. This guidance should help companies keep down the cost of compliance, but it also means that companies have to perform their assessment with qualified individuals in a way that is consistent with the requirements of AS 2.

Controls operate at two levels within any organization. Entity-level controls are pervasive and can affect many different financial statement accounts. For example, a company's hiring and training policies will affect the way in which individual control procedures are performed. Companies that hire qualified people and train them properly will have much greater success when it comes times for those people to perform their jobs. The converse also is true. In that sense, hiring and training policies can have an effect on many different financial statement accounts.

Activity-level controls, on the other hand, are restricted to one transaction type. For controls over case disbursements will affect cash disbursements only and will have no impact on other accounts, such as the recording of goodwill or the depreciation of fixed assets.

In the year of implementation, many companies and their auditors adopted a bottom-up approach in which they started by identifying all of the companies activity-level controls and then documenting and testing each of these to determine whether internal control as a whole was effective. As you can imagine, this approach was extremely time-consuming and costly. Moreover, not only is it not required, it is not even contemplated by AS 2.

The method described by the auditing standard is the exact opposite of this approach. In a top-down approach you begin at the top, at the entity-level. You then identify the most significant accounts and transaction types at the organization and the control objectives for those accounts and transactions. Once you determine the control objectives, you identify those controls that are in place to meet those objectives. Those controls, and only those controls, are then tested and evaluated.

By using a top-down approach the company:

Tests only those controls related to significant accounts and transactions, which eliminates the need to understand the process and assess controls in those areas that do not affect the likelihood that the company's financial statements could be materially misstated.

Tests the minimum number of controls necessary to meet the control objective. Redundant controls (and there are many of these) are not tested.

Implementing a top-down approach requires company management to exercise its judgment. How do you decide which accounts and transactions are "significant" and which are insignificant? If you are not going to test all the control activities for significant accounts and transactions, how do you determine which ones to test?

To make these and other decisions you should consider the related risk of material misstatement of the financial statements. As described in more detail in Chapter 2 of this book, control activities are designed to meet identified risks of misstatement. For example, one of the risks of misstatement is that the company may fail to record all of its accounts payable as of year-end. To mitigate this risk, management will design and implement procedures at the company to make sure that that all payables get recorded.

Do these controls need to be documented and tested? It depends on the relative significance of the risk of failing to record all accounts payable. What is the likelihood that the failure to record all accounts payable would result in a material misstatement of the company's financial statements? The answer to this question will help you determine whether to document and test the controls over accounts payable.

Performing an assessment of internal control is not a "paint-by-numbers" exercise. It is a process that requires a great deal of judgment. The primary benchmark for making these judgments risk, that is the risk that the financial statements would be materially misstated if the identified control was ineffective.

It is vital that you coordinate your project with the entity's independent auditors. This coordination process begins at the planning phase of the project and continues at each subsequent phase. Proper coordination between your team and the independent auditors will facilitate an effective and efficient audit. A lack of coordination with the auditors could result in a variety of negative, unforeseen consequences, including:

Duplication of effort

Reperformance of certain tests

Performance of additional tests or expansion of the scope of the engagement

Misunderstandings relating to the definition or reporting of material weaknesses

You should reach a consensus with the entity's independent auditors on key planning decisions, including:

The overall engagement process and approach

The scope of your project, including locations or business units to be included

Preliminary identification of significant controls

The nature of any internal control deficiencies noted by the auditors during their most recent audit of the entity's financial statements

Tentative conclusions about what will constitute a significant deficiency or material weakness

The nature and extent of the documentation of controls

The nature and extent of the documentation of tests of controls

The degree to which the auditors will rely on the results of your test work to reach their conclusion

During the early phases of the project, it may not be possible to obtain a definitive understanding with the auditors on all significant planning matters. In those situations, you should still work with the auditors to reach a consensus regarding:

A clear understanding of the issue(s) that need resolution

The additional information required to reach a resolution

The process to be followed to resolve the matter

An estimated time frame for the process to be completed and the issue(s) to be resolved

The passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act signaled the start of a new era in financial reporting, on par with the requirement of 70 years ago that the company's financial statements be audited by an independent CPA. Then, the capital markets looked to the CPA profession for help in implementing this new requirement. Now members of the profession—whether in public practice or employed in industry—seem equally well positioned to make a significant contribution as our country's financial reporting process embarks on another new direction.