Paul Rosenfield, CPA

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) conducted an experiment in its Statement No. 33, "Financial Reporting and Changing Prices," issued in 1979, in which certain companies were required to present one set of supplementary information stated in a unit of measure defined in terms of the general purchasing power of the dollar reflecting changes in the general level of prices—inflation reporting—and one set adjusted to current buying prices—current cost reporting. (Other bases reflecting price changes that have been advocated for financial reporting, such as current selling prices and the discounted amount of future cash receipts and payments, were not part of FASB Statement No. 33 and are not considered in detail in this chapter.)

The unit of measure in a set of financial statements is defined in terms of the unit of the money of a country (or of much of a continent, in the case of Euros). Money has three kinds of powers in terms of which the unit of measure for financial statements can be defined. The first is its debt-paying power, which U.S. paper money implies is its primary or only power: "This note is legal tender for all debts, public, and private." U.S. dollars have only one kind of power to discharge debts denominated in U.S. dollars, which never changes. Tendering one U.S. dollar always discharges one U.S. dollar of debt.

The second kind of power of money of interest in financial reporting is its specific purchasing power. Money can be used to buy specific things: Most things for sale in a country are exchangeable for the money or promises of the money of the country. A specific purchasing power of a given quantity of money is its power to buy a single specific kind of good or service. That power depends on the price of that good or service. There is one kind of specific purchasing power for each kind of good or service money can buy. Prices, ratios of exchange, are stated in numbers of units of money. The prices of specific kinds of goods and services can change, so the specific purchasing powers of the quantity of money can change.

The third kind of power of money of interest in financial reporting is its general purchasing power. A general purchasing power of a given quantity of money is its power to buy a specified group of diverse kinds of goods and services, often called a basket of goods and services. A quantity of money at a point in time has one kind of general purchasing power for each kind of basket that can be specified. Skinner observed that "Some people argue that an index of prices in general has no meaning,"[243] but specifying a basket specifies a general purchasing power; it exists because it is a power that exists to buy a selection of things that exist. The prices of the goods and services in the basket can change, so each kind of general purchasing power of the quantity of money can change.

Nevertheless, "... most accountants and users of financial statements have been inculcated with a model of financial reporting that assumes stability of the [general purchasing power of the] monetary unit...."[244] We financial reporters should not act as though something important to financial reporting is the opposite of what it is.

A specified quantity of money, such as that specified in a price, thus involves debt-paying power, specific purchasing power, and general purchasing power. When money is spent (sacrificed), the holder of the money gives up powers (incurs costs) of those kinds. When money is received, the recipient receives powers of those kinds.

Current generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) in the United States use a unit of measure defined in terms of the debt-paying power of the unit of money. One of the sets of financial statements mandated by FASB Statement No. 33 incorporated a definition of the unit of measure in terms of the general purchasing power of the unit of money.

"Current buying prices" is a shorthand expression. There are three ways to express current buying prices longhand, stated below. Not considering those longhand expressions has misled proponents of replacing acquisition costs with current buying prices (current costs) as the general basis for financial statements. All such longhand expressions make it clear that current buying prices do not belong in statements of financial position or income statements. (Some have suggested that current buying prices may be helpful as surrogates for or predictors of supposed future events or as surrogates for other attributes.)

The overriding reason they do not belong in financial statements is that once a reporting entity buys an asset, it is finished with the buying market for the asset. It cannot buy an asset it owns while it owns it (obviously); as Sterling states, there are "... entry values of unowned assets...."[245] (Entry values and exit values are common, even more abbreviated expressions for current buying and selling prices.) Nevertheless, Sterling stated that "I mean by 'entry values' the process of valuing assets at their current purchase price.... [but] the relevance of entry values of owned assets escapes me."[246] But it is impossible to "valu[e] assets at their current purchase price," and there is no issue of whether current buying prices of owned assets are or are not relevant. Such prices don't exist. This exemplifies the trap of referring to "entry price" or "entry value" rather than using the following longhand expression: "the price at which the reporting entity can currently buy an asset it owns," which can be seen as obvious nonsense. (In contrast, current selling prices exist. A reporting entity can sell assets it holds, though it cannot buy assets it holds.) Others fell into the same trap:

A given asset [owned by a firm] may have several different market prices [including] what it would cost [the firm] to purchase [it] now.... (Thomas, Main, p. 36)

A current ... price for an asset [owned by a firm] can be obtained from ... markets ... in which the firm could buy the asset.... (Edwards and Bell, Income, p. 75)

Current costs represent the exchange price that would be required today [for an entity] to obtain the same asset or its equivalent. (Hendriksen and van Breda, Theory, p. 495)

Edwards and Bell even state that a reporting entity can buy an asset it owns from a competitor! "If the asset being valued is a good in process or a finished good ... the cost to purchase it from a competitive firm would...."[247]

Like time and cause and effect, assets go in only one direction; for assets, that direction is from purchase to use, if any, and to sale. After an asset is bought by a reporting entity, the entity can only either use it or send it to its selling markets for the asset or its products (if a reporting entity has to dump an asset it holds, it may sell it in the same place it bought it, but that is still a selling market for the reporting entity, and it sells it for its selling price in that market). But we financial reporters spin theories to avoid that conclusion, though current buying prices are even worse than acquisition costs, because acquisition costs at least are attributes of the assets. Current buying prices violate the number one qualitative criterion for financial statements, representativeness,[248] because they purport to represent nothing about the assets held by the reporting entity.

Note that this does not refer to the price at which the reporting entity can currently buy an asset similar to an asset it owns, which is another kind of current buying price and a second longhand expression for current buying prices. Systems using these kinds of current buying prices have also been advocated for replacement of acquisition cost as the general basis for financial statements. The fatal defect of this proposal is that such prices are not attributes of the assets held by the reporting entity. They are attributes of assets not held by the reporting entity—assets it does not hold but can buy. Though theories are spun attempting to justify the proposal, such prices should not be used because they are not part of the history of the reporting entity (except for the history of its buying opportunities, which should not be presented in financial statements), and financial statements are supposed to be confined to reporting financial aspects of its history.

A third longhand expression for current buying prices is the amount of money it would cost to recoup the value lost when a reporting entity is deprived of an asset—its so-called deprival value. The fatal defect of proposals to use this idea of current buying prices as the basis for the amounts at which to measure assets in financial statements is that it involves a factor that is contrary to fact—fiction. If an asset held is to be measured at deprival value, the underlying assumption is that the reporting entity has been deprived of it. However, the reporting entity cannot both hold it and have been deprived of it. A report of history should not involve fiction.

The use of current buying prices follows the law of the hammer, which states that if you give a four-year-old a hammer, he will discover that everything needs hammering. If you give a financial reporting theorist current buying prices, he will discover that financial statements cannot do without them. That is the opposite of how advances in technology should proceed. A technical problem should first be identified and analyzed and a mechanism then sought to solve it, rather than vice versa.

One of the sets of financial statements mandated by FASB Statement No. 33 incorporated current buying prices as the attribute to emphasize in financial statements.

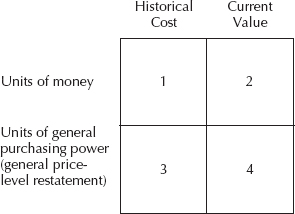

Inflation reporting involves the definition of the unit of measure. In contrast, current cost reporting, one of the varieties of current value reporting, involves selection of attributes to measure. Exhibit 17.1 illustrates the relationship.

They are separate responses to separate problems: "...the question of current cost is one of 'value,' and the question of general price level adjustments is one of 'scale.' These are two separate issues."[249] However, the separation is often disregarded, for example: "... general price level accounting and current-value accounting are competing alternative measures for dealing with problems created by inflation."[250]

The effect on income statements in general of changing the attribute that's measured is merely to change the periods in which income is reported: "...[the] choice of attributes to be measured ... do[es] not affect the amounts of comprehensive income ... over the life of an enterprise but do[es] affect the time and way parts of the total are identified with the periods that constitute the entire life."[251] Changing the unit of measure, in contrast, changes the amount of overall reported income.

The FASB in effect rescinded its Statement No. 33 by issuing its Statement No. 89, in 1986. Flegm celebrated Statement No. 33's failure: "One of the challenges that academics should address ... is why Statement No. 33 was such a dismal failure...."[252] This chapter takes up that challenge.

Figure 17.1. Relationship between General Price-Level Restatement and Current Value Accounting (Source: Paul Rosenfield, "The Confusion between General Price-Level Restatement and Current Value Accounting," Journal of Accountancy, October 1972.)

Before the stock market crash of 1929, many companies increased the amounts at which they reported their assets, mainly their land, buildings, and machinery, to make them more current, based on the belief that investors were influenced by reported asset amounts more than by reported income amounts, in contrast with the opposite belief today. After the crash, the write-ups were reversed and many companies even wrote their assets down below acquisition cost.

Many people said those increased asset amounts contributed to the increase in prices of common stocks leading up to the crash; for example, Brown referred to "The speculative orgy of the predepression days based on frequent and optimistic revaluations of assets, dividend distributions based on inflated values, and heavy reliance on book values of stock...."[253] Investors who had lost money rightly or wrongly placed part of the blame on us financial reporters who had made or permitted the write-ups. Thus burned, we financial reporters changed rules, instituted new rules—"... in the United States ...upward revaluation was virtually outlawed in the 'thirties...."[254]—and vowed we would never again permit assets to be reported at amounts greater than their acquisition costs: Littleton, an influential professor at the time, said that "...few people wish to see enterprises and accounting tangle again with the revaluation approach often used in the 1920s and 1930s."[255]

It was said that the financial reporters of that day would all have to die before reporting of assets at greater than acquisition cost would again be permitted; as the economist Paul Samuelson said, "knowledge advances 'funeral by funeral.' "[256] The historian Jacques Barzun agrees: "...old resisters could be gradually argued into their graves."[257] Even today, issuers of financial reports feel much the same. For example, Flegm recently said that "It was common practice in the 1920s to 'create' values through such questionable practices as writing up one's assets, but the 1929 stock market crash and the subsequent congressional hearings which resulted in the establishment of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) ended such 'voodoo accounting.' "[258]

After more than a generation, double-digit inflation plus a nudge from the chief accountant of the SEC caused us financial reporters to reconsider. First, the SEC in 1976[259] and then the FASB in 1979 in FASB Statement No. 33 temporarily required large companies to present supplementary information reflecting current prices of assets held—often higher than their acquisition costs—and reflecting the financial effects of inflation. For the moment, though, the primary financial statements reflect the Depression mentality of acquisition cost now and evermore. The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Special Committee on Financial Reporting reflected that mentality in 1994: "Despite the periodic call to do so, [standard setters] should not pursue a value-based accounting model."[260]

FASB Statement No. 33 had two major defects: (1) its use of supplementary statements and (2) its use of current buying prices.

The FASB thought that "Supplementary financial statements, complete or partial, may be useful, especially to introduce and to gain experience with new kinds of information."[261] Solomons said as much: "The easiest way for the board to innovate is through requirements to provide supplementary information. That way, change—even radical change—can be introduced for a trial period without disrupting GAAP."[262] But people said they did not know what to do with the information, and that is why the experiment failed. The FASB terminated the experiment.

The reason people did not know what to do with the supplementary information was that it competed with the usual financial statement information stated in a unit of measure defined in terms of the debt-paying power of the dollar, which pertained to the same things as the supplementary information but gave different amounts. The debt-paying power information was familiar; the supplementary information was unfamiliar: "... the presentation of financial statements on the traditional basis supplemented by statements on any contemporary basis will only increase, not diminish, confusion....; ... where the supplementary information is contradictory of the principal information ... recipients know not what to do with it."[263] The competition was too much for the supplementary information. That was the best way to condemn inflation reporting.

Inflation reporting should not be toyed with. One set of financial statements should be presented. The unit of measure in the financial statements should be defined in terms of the consumer general purchasing power of the unit of money. (Mexico, Chile, and Venezuela, e.g., did that.) People would know what to do with such financial statements—the same things they do with current-style financial statements, only better.

The failure of FASB Statement No. 33 was a mixed blessing. It was defectively designed: It involved supplementary statements, which denigrated the experimental information, and it used a factor that it called an attribute of assets that is not an attribute of assets. It is fortunate that it failed. An unfortunate effect of its failure, however, is that interest in reflecting changing prices in financial statements in the periods in which they change has at least temporarily diminished since then. Thus, earnings management by the faulty design of GAAP, which is discussed in Chapter 6, continues to be facilitated.

Though a failure, FASB Statement No. 33 was a noble failure, not, as Flegm called it, a dismal failure, because it marked a significant departure from the kind of financial reporting practiced throughout most of the twentieth century, going back at least to the stock market crash. For a shining moment, the profession abandoned its terror of reflecting changes in the prices of assets while they are held, at least in supplementary statements.

AICPA, Special Committee on Financial Reporting, Comprehensive Report of the Special Committee on Financial Reporting, "Improving Business Reporting—A Customer Focus," 1994.

Barzun, Jacques, From Dawn to Decadence (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 2000).

Belkaoui, Ahmed Riahi, Accounting Theory, 3rd ed. (New York: The Dryden Press, 1993).

Brown, Clifford D., The Emergence of Income Reporting, in Coffman et al., Perspectives.

Chambers, R. J., Accounting, Finance, and Management (Chicago: Arthur Andersen & Co., 1969).

———, "Second Thoughts on Continuously Contemporary Accounting", Abacus, September 1970.

———, "Accounting Education for the Twenty-first Century", Abacus, Vol. 23, No. 2, 1987.

Coffman, Edward N., Tondkar, Rasoul H., and Previts, Gary John, Historical Perspectives of Selected Financial Accounting Topics (Homewood, IL: Irwin, 1993).

Edwards, Edgar O., and Bell, Philip W., The Theory and Measurement of Business Income (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961).

Financial Accounting Standards Board, Statement of Concepts No. 2, "Qualitative Characteristics of Accounting Information."

———, Statement of Concepts No. 5, "Recognition and Measurement in Financial Statements of Business Enterprises."

———, Statement of Concepts No. 6, "Elements of Financial Statements."

———, Statement of Standards No. 89, "Financial Reporting and Changing Prices."

Flegm, Eugene H., Letter to the Editor of Barron's, January 13, 1986.

———, "The Limitations of Accounting", Accounting Horizons, September 1989.

Hendriksen, Eldon S., and van Breda, Michael F., Accounting Theory, 5th ed. (Boston: Richard D. Irwin, Inc., 1992).

Kam, Vernon, Accounting Theory, Second edition. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1990).

Littleton, A. C., Structure of Accounting Theory (New York: American Accounting Association, 1953).

Rosenfield, Paul, Critique: Inflation and the Lag in Accounting Practice, in Sterling and Bentz, Perspective.

———, "The Confusion Between General Price-Level Restatement and Current Value Accounting", Journal of Accountancy, October 1972.

Skinner, Ross M., Accounting Standards in Evolution (Canada: Holt, Rinehart and Winston of Canada, Limited, 1987).

Solomons, Making Accounting Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986).

Sterling, Robert R., Toward a Science of Accounting (Houston: Scholars Book Co., 1979).

Sterling, Robert R., and Bentz, William F., Accounting in Perspective (Dallas: South-Western Publishing Co., 1971).

Thomas, Arthur L., Financial Accounting: The Main Ideas, Second edition. (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company, Inc., 1975).

Wade, Nicholas, "From Ants to Ethics: A Biologist Dreams of Unity of Knowledge", New York Times, May 12, 1998.

[243] 1Ross M. Skinner, Accounting Standards in Evolution (Holt, Rinehart, and Winston of Canada, Limited, 1987), p. 554.

[244] 2FASB, Statement of Standards No. 89, "Financial Reporting and Changing Prices," Lauver dissent.

[245] 3Robert R. Sterling, Toward a Science of Accounting (Houston: Scholars Book Co., 1979), p. 101, emphasis added.

[246] 4Id., p. 124.

[247] 5Edgar O. Edwards and Philip W. Bell, The Theory and Measurement of Business Income (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961), p. 91.

[248] 6This is the first part of the FASB's criterion of representational faithfulness (the second part is faithfulness). FASB Statement of Concepts No. 2, "Qualitative Characteristics of Accounting Information."

[249] 7Vernon Kam, Accounting Theory, 2nd ed. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1990), p. 449.

[250] 8Ahmed Riahi Belkaoui, Accounting Theory, 3rd ed. (New York: The Dryden Press, 1993), p. 305.

[251] 9FASB, Statement of Concepts No. 6, "Elements of Financial Statements," par. 73.

[252] 10Eugene H. Flegm, "The Limitations of Accounting," Accounting Horizons, September 1989, p. 95.

[253] 11Clifford D. Brown, "The Emergency of Income Reporting," in Coffman et al., Perspectives, p. 69.

[254] 12R. J. Chambers, "Second Thoughts on Continuously Contemporary Accounting," Abacus, September 1970, p. 40.

[255] 14A. C. Littleton, Structure of Accounting Theory (New York: American Accounting Association, 1953), p. 213.

[256] 15Nicholas Wade, "From Ants to Ethics: A Biologist Dreams of Unity of Knowledge," New York Times, May 12, 1998, p. F6.

[257] 16Jacques Barzun, From Dawn to Decadence (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 2000), p. 38.

[258] 17Eugene H. Flegm, Letter to the Editor of Barron's, January 13, 1986, p. 48.

[259] 18Accounting Series Release 190.

[260] 19AICPA, Special Committee on Financial Reporting, Comprehensive Report of the Special Committee on Financial Reporting, "Improving Business Reporting—A Customer Focus," 1994, p. 95.

[261] 20FASB, Statement of Concepts No. 5, "Recognition and Measurement in Financial Statements of Business Enterprises."

[262] 21Policy, p. 196. I once said much the same: "One thing I know is that we cannot get the general price-level statements to be the only statements now. That would be absolutely impossible, considering the educational job that would be required for both accountants and users, to cite just one problem." (Rosenfield, "Critique," p. 162.) Experience with FASB Statement No. 33, as discussed in the text, has caused me to repent of that sentiment.

[263] 22R. J. Chambers, "Accounting Education for the Twenty-first Century," Abacus, Vol. 23, No. 2, 1987, p. 195; and Accounting, Finance, and Management (Chicago: Arthur Andersen & Co., 1969), p. 440.