Frederick Gill, CPA

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants

Accounting Standards Team

Senior Technical Manager

The views of Mr. Gill, as expressed in this publication, do not necessarily reflect the views of the AICPA. Official positions are determined through certain specific committee procedures, due process, and deliberation.

FASB Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 6, "Elements of Financial Statements," defines liabilities as:

[P]robable future sacrifices of economic benefits arising from present obligations of a particular entity to transfer assets or provide services to other entities in the future as a result of past transactions or events.

Probable is used with its usual general meaning and refers to that which can reasonably be expected on the basis of available evidence but is not certain. Obligation is broader than "legal obligation," referring to duties imposed legally or socially and to that which one is bound to do by contract, promise, or moral responsibility. Concepts Statement No. 6 (par. 36) elaborates that a liability has three essential characteristics:

[I]t embodies a present duty or responsibility to one or more other entities that entails settlement by probable future transfer or use of assets at a specified or determinable date, on occurrence of a specified event, or on demand,

the duty or responsibility obligates a particular entity, leaving it little or no discretion to avoid the future sacrifice, and

the transaction or other event obligating the entity has already happened.

The furnishing of goods, services, or money to another party is usually a prerequisite for the recording of a liability. Agreements for the exchange of resources in the future that are at present unfulfilled commitments on both sides are not recorded until one of the parties at least partially fulfills its commitment. The effects of some executory contracts, however, are recorded, for example, losses under purchase commitments. The FASB stated the following in Concepts Statement No. 5 (par. 107):

Several respondents urged the Board to address in this Statement certain specific recognition and measurement issues including definitive guidance for recognition of contracts that are fully executory (i.e., contracts as to which neither party has as yet carried out any part of its obligations, which are generally not recognized in present practice) and selection of measurement attributes for particular assets and liabilities. Those issues have long been, and remain, unresolved on a general basis.

Items such as minority interest and deferred gross profit on installment sales are sometimes found on the right side of balance sheets. On occasion, such items are confused with liabilities. Neither minority interest nor deferred gross profit on installment sales is a liability, and the presentation of those items in financial statements should be such as to clearly segregate them from any long-term liabilities.

APB Opinion No. 10, "Omnibus Opinion—1966," states in paragraph 7 that "It is a general principle of accounting that the offsetting of assets and liabilities in the balance sheet is improper except where a right of setoff exists." FASB Interpretation No. 39, "Offsetting of Amounts Related to Certain Contracts," clarifies that a right of setoff is a debtor's legal right, by contract or otherwise, to discharge all or a portion of the debt owed to another party by applying against the debt an amount that the other party owes to the debtor. The Interpretation states in paragraph 5 that a right of setoff exists when all of the following conditions are met:

Each of two parties owes the other determinable amounts.

The reporting party has the right to set off the amount owed by the other party.

The reporting party intends to set off the amount owed by the other party.

The right of setoff is enforceable at law.

A debtor having a valid right of setoff may offset the related asset and liability and report the net amount.

For purposes of the Interpretation, cash on deposit at a financial institution is to be considered by the depositor as cash rather than as an amount owed to the depositor. Thus, for example, an overdraft in a bank account at a particular bank may not be offset against a cash balance at the same institution because the cash balance is not considered an amount owed to the depositor.

The Interpretation addresses offsetting of amounts recognized for forward, interest-rate swap, currency swap, option, and other conditional or exchange contracts. The fair value of those contracts or an accrued receivable or payable arising from those contracts, rather than the notional amounts or the amounts to be exchanged, is recognized in the statement of financial position. The fair value of contracts in a loss position should not be offset against the fair value of contracts in a gain position unless a right of setoff exists. Similarly, amounts recognized as accrued receivables should not be offset against amounts recognized as accrued payables unless a right of setoff exists. An exception is made to permit offsetting of fair value amounts recognized for forward, swap, and other conditional or exchange contracts executed with the same counterparty under a master netting arrangement, without regard to whether the reporting party intends to set them off. A master netting arrangement exists if the reporting entity has multiple contracts, whether for the same type of conditional or exchange contract or for different types of contracts, with a single counterparty that are subject to a contractual agreement that provides for net settlement of all contracts through a single payment in a single currency in the event of default on or termination of any one contract. Offsetting the fair values recognized for forward, interest rate swap, currency swap, option, and other conditional or exchange contracts outstanding with a single counterparty results in the net fair value of the position between the two counterparties being reported as an asset or a liability in the statement of financial position.

Various accounting pronouncements specify accounting treatments in circumstances that result in offsetting or in a presentation in a statement of financial position that is similar to the effect of offsetting, for example, the accounting for pension plan assets and liabilities under FASB Statement No. 87, "Employers' Accounting for Pensions," and the accounting for advances received on construction contracts under the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Audit and Accounting Guides Construction Contractors and Audits of Federal Government Contractors. Interpretation No. 39 does not modify the accounting treatment prescribed by other pronouncements.

FASB Interpretation No. 41, "Offsetting of Amounts Related to Certain Repurchase and Reverse Repurchase Agreements," modified Interpretation No. 39 to permit offsetting in the statement of financial position of payables and receivables that represent repurchase agreements, without regard to whether the reporting party intends to set them off, if conditions specified in the Interpretation are met.

FASB Concepts Statement No. 5 (par. 67) recognized that items currently reported in financial statements are measured by different attributes, depending on the nature of the item. Liabilities that involve obligations to provide goods or services to customers are generally reported as historical proceeds, which is the amount of cash, or its equivalent, received when the obligations were incurred and may be adjusted after acquisition for amortization or other allocations. Liabilities that involve known or estimated amounts of money payable at unknown future dates, for example, trade payable or warranty obligations, generally are reported at their net settlement value, which is an undiscounted amount. Long-term payables are reported at their present value, discounted at the implicit or historical rate, which is the present value of future outflows required to settle the liability. (See Section 4 for a discussion of how the use of present value and discounting concepts in measuring long-term payables contributes to earnings management by the faulty design of generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP).)

Many liabilities result from financial instruments, for example, bonds and notes payable. (See "Disclosures about Fair Value of Financial Instruments" below for the definition of a financial instrument.) The FASB concluded in Statement No. 133, "Accounting for Derivative Instruments and Hedging Activities," issued in June 1998, that fair value is the most relevant measure for financial instruments and that fair value measurement is practical for most financial assets and liabilities. Paragraph 334 of Statement No. 133 states:

The Board is committed to work diligently toward resolving, in a timely manner, the conceptual and practical issues related to determining the fair values of financial instruments and portfolios of financial instruments. Techniques for refining the measurement of the fair values of financial instruments continue to develop at a rapid pace, and the Board believes that all financial instruments should be carried in the statement of financial position at fair value when the conceptual and measurement issues are resolved.

Only certain liabilities resulting from financial instruments, such as liabilities resulting from derivative financial instruments and guarantees, are currently reported at fair value.

The fair value of a liability is commonly said to be the amount at which that liability could be settled in a current transaction between willing parties, that is, other than in a forced or liquidation transaction. (The ambiguity of that definition is discussed in Section 1.) Quoted market prices in active markets are the best evidence of fair value. Thus, if a quoted market price is available for an instrument, its fair value is the product of the number of trading units of the instrument times that market price. If an instrument trades in more than one market, the price in the most active market for that instrument should be used. If quoted market prices are not available, the estimate of fair value may be based on the best information available in the circumstances, including prices for similar liabilities and the results of using other valuation techniques such as the present value technique.

In February 2000, the FASB issued Concepts Statement No. 7, "Using Cash Flow Information and Present Value in Accounting Measurements". The Board introduced in that Concepts Statement the expected cash flow approach, which focuses on explicit assumptions about the range of possible estimated cash flows and their respective probabilities. That approach differs from the traditional approach to present value applications, which have typically used a single set of estimated cash flows and treated uncertainties implicitly in the selection of a single interest rate.

The Board also concluded in that Concepts Statement that, when using present value techniques to estimate the fair value of a liability, the objective is to estimate the value of the assets required currently to (1) settle the liability with the holder or (2) transfer the liability to an entity of comparable credit standing. In either case, the measurement should reflect the credit standing of the entity obligated to pay. Thus, an improvement in a debtor's credit standing would result in the debtor's reporting a greater liability in its statement of financial position, and deterioration in the debtor's credit standing would result in the debtor reporting a smaller liability. The income statement results of that treatment have been challenged.

FASB Concepts Statements do not establish standards prescribing accounting procedures or disclosure practices for particular items or events. They do, however, guide the Board in developing accounting and reporting standards and may provide some guidance in analyzing new or emerging problems of financial accounting and reporting in the absence of applicable authoritative pronouncements.

At the time of this writing, the FASB has on its agenda a project to provide guidance for measuring and reporting essentially all financial assets and liabilities at fair value in the financial statements.

FASB Statement No. 107, "Disclosures about Fair Values of Financial Instruments" (par. 3), defines a financial instrument as—

Cash, evidence of an ownership interest in an entity, or a contract that both:

Imposes on one entity a contractual obligation (1) to deliver cash or another financial instrument to a second entity or (2) to exchange other financial instruments on potentially unfavorable terms with the second entity.

Conveys to that second entity a contractual right (1) to receive cash or another financial instrument from the first entity or (2) to exchange other financial instruments on potentially favorable terms with the first entity.

Contractual obligations encompasses both those that are conditioned on the occurrence of a specified event and those that are not. All contractual obligations that are financial instruments meet the definition of a liability set forth in FASB Concepts Statement No. 6, "Elements of Financial Statements," although some may not be recognized as liabilities in financial statements, that is, they may be "off-balance sheet," because they fail to meet some other criterion for recognition. For some financial instruments, the obligation is owed to or by a group of entities rather than a single entity.

Examples of contractual obligations that are financial instruments include loans; bonds; notes payable; trade payables; deposit liabilities of banks; interest rate swaps; foreign currency contracts; put and call options on stock, foreign currency, or interest rate contracts; commitments to extend credit; and guarantees of the indebtedness of others, regardless of whether explicit consideration was received for the guarantees.

FASB Statement No. 107 requires disclosure, either in the body of the financial statements or in the accompanying notes, of (1) the fair value of financial instruments, regardless of whether recognized in the statement of financial position, for which it is practicable to estimate that value; and (2) the method(s) and significant assumptions used to estimate the fair value of financial instruments.

Practicable, in this context, means that an estimate of fair value can be made without incurring excessive costs.[364]

If it is not practicable to estimate the fair value of a financial instrument or a class of financial instrument, Statement No. 107 requires disclosure of the following:

Information pertinent to estimating the fair value of that financial instrument or class of financial instruments, such as the carrying amount, effective interest rate, and maturity

The reasons why it is not practicable to estimate fair value

Quoted market prices, if available, should be used to measure fair value. If quoted market prices are not available, management's best estimate of fair value may be based on the quoted market price of a financial instrument with similar characteristics or on valuation techniques (e.g., the present value of estimated cash flows using a discount rate commensurate with the risks involved, option pricing models, or matrix pricing models). In estimating the fair value of deposit liabilities, a financial entity should not take into account the value of core deposit intangibles. For deposit liabilities without defined maturities, the fair value to be disclosed is the amount payable on demand at the date of the financial statements.

The disclosures about fair value are not required for:

Employers' and plans' obligations for pension benefits, other postretirement benefits including health care and life insurance benefits, employee stock option and stock purchase plans, and other forms of deferred compensation arrangements

Substantively extinguished debt

Insurance contracts other than financial guarantees and investment contracts

Lease contracts

Warranty obligations

Unconditional purchase obligations

In addition, no disclosure is required for trade payables when their carrying amount approximates fair value.

There is a general presumption that, if a contractual obligation to pay money on a fixed or determinable date (referred to below for convenience as a note) was exchanged for property, goods, or services in a bargained transaction entered into at arm's length, the rate of interest stipulated by the parties to the transaction represents fair and adequate compensation to the supplier for the use of the money. That presumption does not apply, however, if:

Interest is not stated.

The stated interest rate is unreasonable.

The stated face amount of the note is materially different from the current cash sales price for the same or similar items or from the market value of the note at the date of the transaction.

In those circumstances, APB Opinion No. 21, "Interest on Receivables and Payables," requires that the note, the sales price, and the cost of the property, goods, or services exchanged for the note be recorded at the fair value of the property, goods, or services or at an amount that reasonably approximates the market value of the note, whichever is more clearly determinable. Established exchange prices may be used to determine the fair value of the property, goods, or services exchanged for the note, or, when notes are traded in an open market, the market rate of interest and market value of the notes are evidence of fair value. In other circumstances, the present value of the note should be determined by discounting all future payments on the note using an imputed interest rate.

The interest rate should be selected by reference to interest rates on similar instruments of the same or comparable issuers, with similar maturities, security, and so on. APB Opinion No. 21 notes that the objective is "to approximate the rate that would have resulted if an independent lender had negotiated a similar transaction under comparable terms and conditions with the option to pay the cash price upon purchase or to give a note for the amount of purchase which bears the prevailing rate of interest to maturity." The difference between the amount at which the note is recorded and the face amount of the note is referred to as a premium or discount.

The premium or discount is amortized[365] as interest expense or income over the life of the note using the interest method, or capitalized in accordance with FASB Statement No. 34, "Capitalization of Interest Cost." The interest method allocates the premium or discount over the life of the note in such as way as to result in a constant rate of interest when applied to the amount outstanding at the beginning of any given period.[366] The interest method is discussed further in Section 25.5.

APB Opinion No. 21 does not apply to:

Receivables and payables arising from transactions with customers or suppliers in the normal course of business that are due in customary trade terms not exceeding approximately one year

Amounts that will be applied to the purchase price of the property, goods, or services involved, for example, deposits or progress payments on construction contracts, advance payments for acquisition of resources and raw materials, advances to encourage exploration in the extractive industries

Amounts intended to provide security for one party to an agreement, for example, security deposits, retainages on contracts

The customary cash lending activities and demand or savings deposit activities of financial institutions whose primary business is lending money

Transactions where interest rates are affected by the tax attributes or legal restrictions prescribed by a governmental agency, for example, industrial revenue bonds, tax exempt obligations, government guaranteed obligations, or income tax settlements

Transactions between a parent and its subsidiary or between subsidiaries of a common parent

Accounting Research Bulletin (ARB) No. 43, "Restatement and Revision of Accounting Research Bulletins," Chapter 3, paragraph 7, as amended by FASB Statement No. 78, "Classification of Obligations That Are Callable by the Creditor," states, in part:

The term current liabilities is used principally to designate obligations whose liquidation is reasonably expected to require the use of existing resources properly classifiable as current assets, or the creation of other current liabilities. As a balance-sheet category, the classification is intended to include obligations for items which have entered into the operating cycle, such as payables incurred in the acquisition of materials and supplies to be used in the production of goods or in providing services to be offered for sale; collections received in advance of the delivery of goods or performance of services; and debts which arise from operations directly related to the operating cycle, such as accruals for wages, salaries, commissions, rentals, royalties, and income and other taxes. Other liabilities whose regular and ordinary liquidation is expected to occur within a relatively short period of time, usually twelve months, are also intended for inclusion ... The current liability classification is also intended to include obligations that, by their terms, are due on demand or will be due on demand within one year (or operating cycle, if longer) from the balance sheet date, even though liquidation may not be expected within that period. It is also intended to include long-term obligations that are or will be callable by the creditor either because the debtor's violation of a provision of the debt agreement at the balance sheet date makes the obligation callable or because the violation, if not cured within a specified grace period, will make the obligation callable.

Under FASB Statement No. 109, "Accounting for Income Taxes," deferred tax liabilities (i.e., the deferred tax consequences attributable to taxable temporary differences) are classified as current or noncurrent based on the classification of the related asset or liability for financial reporting. A deferred tax liability that is not related to an asset or liability, including deferred tax assets related to carryforwards, is classified according to the expected reversal date of the temporary difference.

A suggestion has been made to eliminate the classification of current liabilities (and current assets). See Loyd Heath, Accounting Research Monograph No. 3, "Financial Reporting and the Evaluation of Solvency," AICPA, 1978.

If part of a long-term liability matures or otherwise becomes payable within one year after the balance sheet date, for example, serial maturities of long-term obligations and amounts required to be expended within one year under sinking fund provisions, that part of the liability should be classified as current.

Under FASB Statement No. 6, "Classification of Short-Term Obligations Expected to Be Refinanced," short-term obligations other than obligations arising from transactions in the normal course of business that are due in customary terms are classified as noncurrent if:

The enterprise intends to refinance the obligations on a long-term basis.

The intent to refinance on a long-term basis is evidenced either by (a) an actual post-balance-sheet-date issuance of long-term debt or equity securities or (b) the enterprise having entered into a firm agreement, before the balance sheet is issued, to make an appropriate refinancing.

If short-term obligations are excluded from current liabilities pursuant to Statement No. 6, the financial statements should disclose:

A general description of the financing arrangement

Terms of any new obligation incurred or expected to be incurred, or equity securities issued or expected to be issued, as a result of the refinancing

Obligations that do not qualify for exclusion from current liabilities based on expected refinancing include obligations for items that have entered into the operating cycle, such as payables incurred in the acquisition of materials and supplies to be used in the production of goods or in providing services to be offered for sale; collections received in advance of the delivery of goods or performance of services; and debts that arise from operations directly related to the operating cycle, such as accruals for wages, salaries, commissions, rentals, royalties, and income and other taxes.

FASB Interpretation No. 8, "Classification of a Short-Term Obligation Repaid Prior to Being Replaced by a Long-Term Security," clarified that, if a short-term obligation is repaid after the balance sheet date and subsequently a long-term obligation or equity securities are issued whose proceeds are used to replenish current assets before the balance sheet is issued, the short-term obligation may not be excluded from current liabilities at the balance sheet date.

FASB Statement No. 78, "Classification of Obligations That Are Callable by the Creditor," states that current liability classification includes obligations that are due on demand or that will be due on demand within one year (or operating cycle, if longer) from the balance sheet date, even though liquidation may not be expected within that period.

Current classification also applies to long-term obligations that are or could become callable by the creditor either because the debtor's violation of a provision of the debt agreement at the balance sheet date makes the obligation callable or because the violation, if not cured within a grace period, will make the obligation callable. However, long-term classification is appropriate if the creditor has waived or subsequently lost the right to demand repayment for more than a year, or if it is probable that the violation will be cured within a grace period. In the latter case disclosure is required of the circumstances.

Loan agreements may specify the debtor's repayment terms but may also enable the creditor, at his discretion, to demand payment at any time. The loan arrangement may have wording such as "the term note shall mature in monthly installments as set forth therein or on demand, whichever is earlier," or "principal and interest shall be due on demand, or if no demand is made, in quarterly installments beginning on ..." The Emerging Issues Task Force (EITF) in Issue No. 86-5 concluded that such an obligation should be considered a current liability in accordance with FASB Statement No. 78. Further, under FASB Technical Bulletin No. 79-3, "Subjective Acceleration Clauses in Long-Term Debt Agreements," the demand provision is not a subjective acceleration clause as discussed below.

FASB Statement No. 6 defines a subjective acceleration clause contained in a financing agreement as one that would allow the cancellation of an agreement for the violation of a provision that can be evaluated differently by the parties. The inclusion of such a clause in an agreement that would otherwise permit a short-term obligation to be refinanced on a long-term basis would preclude that short-term obligation from being classified as long term. However, Statement No. 6 does not address financing agreements related to long-term obligations. Under FASB Technical Bulletin No. 79-3, the treatment of long-term debt with a subjective acceleration clause would vary depending on the circumstances. In some situations, only disclosure of the existing clause would be required. Neither reclassification nor disclosure would be required if the likelihood of the acceleration of the due date were remote, such as when the lender historically has not accelerated due dates in similar cases, and the borrower's financial condition is strong and its prospects are good.

Common kinds of current liability include:

Accounts payable and accrued expenses

Short-term notes payable

Dividends payable

Deferred income or revenue

Advances and deposits

Withheld amounts

Estimated liabilities

Accounts payable includes all trade payable arising from purchases of merchandise or services. In published balance sheets this classification normally also includes the liability related to nonfinancial expenses that are incurred continuously, that is, estimated amounts payable for wages and salaries, rent, and royalties. Accrued interest and taxes are also normally included under this caption. Federal income taxes payable are frequently shown separately. The traditional distinction between accounts payable and accrued expenses has tended to disappear, and the common practice today is to include the two items in one heading.

In most cases, notes payable, if shown as a separate category, refers to a definite borrowing of funds, as distinguished from goods purchased through the use of trade acceptances. In this latter case, relatively rare today, notes payable may be presented as part of accounts payable. Dividends payable, the liability to shareholders representing dividend declarations, has traditionally been viewed as a distinct kind of obligation. Deferred revenues appear when collection is made in whole or part prior to the actual furnishing of goods or services. A common example is found in the insurance industry, where premiums are regularly collected in advance. Tickets, service contracts, and subscriptions are other deferred revenue items.

Advances and deposits required to guarantee performance and returnable to the depositor are current liabilities. The returnable containers used in many industries are sometimes included in this category. Withheld amounts, also referred to as agency obligations, result from the collection or acceptance of cash or other assets for the account of a third party. By far the most common items today are federal, state, and local income taxes and payroll taxes withheld from wages.

Estimated liabilities refer to obligations whose amount may be uncertain but the existence of which is unquestioned. Examples include product and service guarantees and warranties.

In some cases, the term accounts payable is restricted to trade creditors' accounts, represented by unpaid invoices for the purchase of merchandise or supplies. In other cases, "accounts payable" includes all unpaid invoices, regardless of their nature. In the accounting system, of course, accounts payable will normally be limited to those transactions for which the company has received an invoice. As stated previously, for financial statement presentation purposes, it is common to include "accrued expenses" in the same balance sheet caption.

Accounts payable may be recorded at gross invoice price (i.e., without deducting discounts offered for prompt payment), or they may be shown net. Although it has been argued that the latter treatment is conceptually superior regardless of the circumstances, in practice receivables tend to be recorded gross. Accounts payable should be recorded net, however, if it is customary in an industry to permit customers to take the discount regardless of when the invoice is paid. If the discount is always allowed, it amounts to a purchase price reduction and should be accounted for as such. If it is allowed only within the discount period, it appears to be more in the nature of a financial item.

The practical difficulties of apportioning small discounts to a series of items on one invoice lead most companies to account for discounts separately from the purchase price of merchandise. Inventory is recorded at the gross price, and the credit balances resulting from the discount are normally netted against the total year's purchases. In principle, year-end adjustments should be made for that portion of the purchases that remains in inventory, but in practice that is rarely done.

Some companies consider that the rate of interest implicit in the usual trade discount is so large that substantial efforts should be devoted to assuring that it is not lost. If conditions preclude the taking of the discount, the difference between the gross price actually paid and the net price that would have been paid may be accounted for as "discount lost." The balance of this account may be interpreted as a financial expense or as evidence of inefficiency in the accounts payable operation.

Bank loans evidenced by secured or unsecured notes payable to commercial banks are a common method of short-term financing. Ordinarily the notes are interest bearing, and in such cases the amount borrowed and the liability to be recorded is the face amount of the note.

In some instances, however, non-interest-bearing or "discount" paper is issued. In such transactions, the bank deducts the interest in advance from the amount given to the borrower, who subsequently repays the full amount of the note.

Assume, for example, that the X Company gives the bank a $1,000 non-interest-bearing 2-month note on a 12 percent basis. The customary entry to record the borrowing is as follows:

Cash | $980 | |

Prepaid interest | 20 | |

Notes payable—bank | $1,000 |

Reporting of the discount as "prepaid interest" has been objected to on the ground that the company has borrowed only $980 and that, therefore, the $20 asset is in no way a prepaid item. Essentially the same problem arises on a long-term basis when bonds are issued at a discount. This matter is discussed in Subsection 25.4(f).

In some cases bank loans or notes are taken for short periods, but with the intent on the part of both borrower and lender that the note will be continuously refinanced. See "Current and Long-Term Liabilities" for a discussion of short-term obligations expected to be refinanced.

Short-term notes payable often arise directly or indirectly from purchases of merchandise, materials, or equipment. If such notes arise directly from purchases, they may be classified in the financial statements with accounts payable. If, however, the notes arise indirectly, or have substantially different payment dates from the usual trade payables, they should be shown separately.

An accounts payable figure can be determined at the balance sheet date from the control account, even though it is normally necessary to review all invoices paid for a reasonable period subsequent to the balance sheet date (search for unrecorded liabilities) to assure that all amounts actually payable at the balance sheet date are properly recorded. In contrast, although some part of the balance of accrued expenses may be determined from recurring expense accruals, in general it is necessary to make a thorough review of all the company's relevant expense accounts—rent, salaries, and so on—to determine the appropriate amount at year end. Thus accrued liabilities (expenses) arise principally only when financial statements are prepared. When preparing the accruals for the different expenses, it is well to keep in mind a sense of balance between the possibility of producing financial statements with every conceivable accrual determined precisely and the added economic value of that precision. In many cases the amount of extra work necessary to estimate certain accruals with extreme accuracy may not be justified by their value to a user of the financial statements. For such immaterial items, relatively rough estimates may suffice.

Outside of financial institutions, it is usually not deemed necessary to accrue interest liabilities from day to day, but it is essential that such liabilities be fully recognized at the close of each period. Accrued interest must be calculated in terms of the various outstanding obligations that bear interest such as accounts, notes, bonds, and capitalized leases.

Full recognition of the liability for wages and salaries earned, but not paid, should be made at the close of each accounting period. Accruals should include not only hourly wages and salaries up to the close of business on the last day of the period, but also estimates of bonuses accrued, commissions earned, employer share of Social Security, and so on.

The liability for unclaimed wages is a related item usually of minimal size but of some legal significance. Payroll checks that have been outstanding for a period should be restored to the bank account and credited to unclaimed wages. In many states the amount of unclaimed wages escheats to the state after a number of years and therefore should be carefully accounted for until such payment is made. In other states the balance of unclaimed wages should be credited to income after a reasonable period.

Prior to FASB Statement No. 43, "Accounting for Compensated Absences," practice related to accruing for vacation pay varied. Most companies did not make such accruals, but a minority did. The prevalent practice was to record compensation for vacation pay as paid. Statement No. 43 requires an employer to accrue a liability for employees' right to receive compensation for future absences if all of the following conditions are met:

The employer's obligation relating to employees' rights to receive compensation for future absences is attributable to services already rendered.

The obligation relates to rights that vest or accumulate. "Accumulate" means that earned but unused rights to compensated absences may be carried forward to one or more periods subsequent to that in which they are earned, even though there may be a limit to the amount that may be carried forward.

Payment of the compensation is probable.

The amount can be reasonably estimated.

If the first three conditions are met but the employer does not accrue the cost because of an inability to reasonably estimate the amount, that fact must be disclosed.

All liabilities for commissions, fees, and similar items should be accrued whenever financial statements are prepared. The principal problem is the determination of the precise amount to be accrued as of a given date. In the case of salespeople's commissions, which are in no sense contingent or conditional, if all sales have been recorded, the precise amount usually is readily determinable. However, commissions are subject to reduction in the event of cancellation of sales, uncollectibility, or other contingencies, it is not possible to make an exact determination of the liability. In such circumstances, a reasonable estimate should be made, taking into consideration the maximum liability based on performance to date, reduced by the expected amount of adjustments due to cancellations and similar contingencies.

In the case of professional services, such as those furnished by accountants and lawyers, the client often finds it difficult to determine the amount due or earned as of a given date. If billing from accountants or lawyers is based on hourly or per diem rates, a statement to date can be obtained and no difficulty is involved in setting up the proper liability. If, however, the engagement has been undertaken for a lump sum, or if the fee will not be determined until the outcome is known, as is common in legal services, the accrual may be very difficult to estimate. If no reasonable estimate can be made, and the amount may be material, the matter should be disclosed in the notes to the financial statements.

The determination of the precise liability for federal corporate income taxes is a complex process. In the rush accompanying preparation of year-end financial statements and annual reports, it is not uncommon to obtain an automatic extension for the filing of a tax return (Form 4868) and to delay the preparation of the return, hence determination of the precise tax liability, until after the financial statements have been prepared. It is necessary, under such circumstances, to make an estimate of the income taxes payable and to record that estimate as a liability in the financial statements.

In some instances, there may be income tax items for which the appropriate tax treatment is unclear. Attitudes toward the treatment of such items vary, but many companies will tend to resolve them in their own favor and await possible disallowance by Internal Revenue Service (IRS) examining agents. The calculation of current and deferred taxes for financial reporting purposes should be based on the probable tax treatment.[367] In addition, interest may need to be accrued for expected adjustments by the taxing authorities.

If the estimate of the tax liability proves to be reasonably accurate, small corrections are usually adjusted to the expense account in the following period.

The determination of the federal income tax liability in interim statements is a more difficult problem, as it requires an estimate of the year's tax burden. For a complete discussion of treatment of tax provisions in interim statements, see Chapter 15.

Tax laws, income tax regulations, and court decisions have mentioned various dates on which property taxes may be said to accrue legally. Such dates include assessment date, date on which tax becomes a lien on the property, and date or dates tax is payable, among others. The IRS holds that property taxes accrue on the assessment date, even if the amount of tax is not determined until later.

The legal liability for property taxes must be considered when title to property is transferred at some point during the taxable year in order to determine whether buyer or seller is liable for the taxes and to adjust the purchase price accordingly. For normal accounting purposes, however, the legal liability concept is held to be secondary to the general consideration that property taxes arise ratably over time. The AICPA (ARB No. 43) states the following:

Generally, the most acceptable basis of providing for property taxes is monthly accrual on the taxpayer's books during the fiscal period of the taxing authority for which the taxes are levied. The books will then show, at any closing date, the appropriate accrual or prepayment....

An accrued liability for real or personal property taxes, whether estimated or definitely known, should be included among current liabilities....

If property is held under a lease agreement with cash rents payable currently to the lessor and the lease is classified as an operating lease under FASB Statement No. 13, rent should be accrued ratably with occupancy as an expense and any unpaid portions shown as current liabilities. For treatment of other lease liabilities, see Chapter 23.

Rent advanced by a tenant represents deferred revenue on the books of the lessor and should also be classed as a liability. Generally, tenants' deposits and sureties should be recorded as separate items. In some jurisdictions, interest must be paid on tenants' deposits and should be accrued.

Advances from officers and employees are related-party transactions that may require disclosure in accordance with FASB Statement No. 57, "Related Party Disclosures," and, for Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) registrants, Regulations S-X and S-K. Related-party disclosures are not required, however, for compensation arrangements, expense allowances, and other similar items in the ordinary course of business. The requirements for disclosure of related-party transactions are discussed in Subsection 25.8(a).

The amount of cash dividends declared, but unpaid, is commonly treated as a current liability in balance sheets. See Chapter 27 for a discussion of the nature and treatment of dividends.

Stock dividends declared, constituting only a rearrangement of the equity accounts, are not recorded as a liability.

Advances by customers or clients that are to be satisfied by the future delivery of goods or performance of services are liabilities and should be shown as such. These items are often labeled "deferred revenue" or "deferred credits." It is better disclosure to provide a title that clearly describes the nature of the item, such as "advances from customers." Commonly such accounts are payable in goods or services rather than in cash, and as a rule a margin of profit will emerge in making such payment. For a discussion of timing of the recognition of income associated with this type of transaction, see Chapter 19, "Revenues and Receivables."

In Statement No. 5, "Accounting for Contingencies" (par. 1), the FASB defines a contingency as:

[A]n existing condition, situation, or set of circumstances involving uncertainty as to possible gain or loss to an enterprise that will ultimately be resolved when one or more future events occur or fail to occur. Resolution of the uncertainty may confirm the acquisition of an asset or the reduction of a liability or the loss or impairment of an asset or the incurrence of a liability.

Not all the uncertainties inherent in the accounting process result in the type of contingencies foreseen by Statement No. 5. Estimates, such as those required in the determination of useful lives, do not make depreciation a contingency. Similarly, a requirement that the amount of a liability be estimated does not produce a contingency as long as there is no uncertainty that the obligation has been incurred. Thus amounts owed for services received, such as advertising and utilities, are not contingencies, although the amounts actually owed may have to be estimated at the time financial statements must be prepared.

In Statement No. 5, the FASB indicates that the likelihood of contingencies occurring may vary and stipulates different accounting depending on that likelihood. The standard (par. 3) suggests three possibilities:

Probable. The future event or events are likely to occur.

Reasonably Possible. The chance of the future event or events occurring is more than remote but less than likely.

Remote. The chance of the event or future events occurring is slight.

Among the kinds of loss contingency suggested by Statement No. 5 are the following:

Collectibility of receivables

Obligations related to product warranties and product defects

Risk of loss or damage of enterprise property by fire, explosion, or other hazards

Threat of expropriation

Pending or threatened litigation

Actual or possible claims or assessments

Risk of loss from catastrophes assumed by property and casualty insurance companies.

Guarantees of indebtedness of others

Obligations of commercial banks under "standby letters of credit"

Agreements to repurchase receivables (or to repurchase the related property) that have been sold

Some of those contingencies involve impairment of an asset rather than the incurrence of a liability.

Contingencies may involve either short-term obligations or long-term obligations, or both. Contingent liabilities are addressed in this section without regard to when they are expected to be settled.

In Statement No. 5, the FASB requires that an estimated loss from a loss contingency be accrued by a charge to income if both of the following two conditions are met:

Information available prior to the issuance of the financial statements indicates that it is probable that an asset had been impaired or a liability had been incurred at the date of the financial statements. This condition implies that it must be probable that one or more future events will occur confirming the fact of the loss.

The amount of loss can be reasonably estimated.

Items become liabilities of an entity only as a result of transactions or other events or circumstances that have already occurred.

As noted immediately above, Statement No. 5 requires that an estimated loss be accrued when it appears that a liability has been incurred and the amount of the loss can be reasonably estimated.

The term reasonably estimated is susceptible to interpretation. In many cases, particularly with litigation and claims, estimates of the amount of the loss may be difficult. Although Statement No. 5 does not define "reasonably estimated" specifically, FASB Interpretation No. 14, "Reasonable Estimation of the Amount of a Loss," attempts to define the term more clearly.

If a reasonable estimate of the loss is a range, Interpretation No. 14 indicates that the "reasonably estimated" criterion is satisfied. If no value in the range is more likely than any other, the minimum amount should be accrued. Thus if the loss from a contingency is probable and will be within a range of $4 million to $6 million, and there is no better estimate within that range, $4 million should be accrued. On the other hand, if within the $4 million to $6 million range, $5.5 million is the most likely outcome, that latter amount should be accrued.

FASB Statement No. 5 states that disclosure of the nature of an accrual made pursuant to its provisions, and in some circumstances the amount accrued, may be necessary for the financial statements to be not misleading.

In many circumstances a loss contingency exists but does not satisfy the two conditions calling for accrual, or exposure to loss exists in excess of the amount accrued. In such cases, Statement No. 5 requires disclosure of the loss contingency. Disclosure is required when there is at least a reasonable possibility that a loss or additional loss may have occurred. The disclosure should indicate the nature of the contingency and should give an estimate of the possible loss or range of loss or state that such an estimate cannot be made.

FASB Statement No. 5 also requires disclosure of guarantees such as (1) guarantees of the indebtedness of others, (2) obligations of commercial banks under "standby letters of credit," and (3) guarantees to repurchase receivables (or, in some cases, to repurchase the related property) that have been sold or otherwise assigned, even though the possibility of loss may be remote. The requirement also applies to other contingencies that in substance have the characteristic of a guarantee. The disclosure must include the nature and amount of the guarantee. Consideration should also be given to disclosing, if estimable, the value of any recovery that could be expected to result, for example, from the guarantor's right to proceed against an outside party.

FASB Interpretation No. 45, "Guarantor's Accounting and Disclosure Requirements for Guarantees, Including Indirect Guarantees of Indebtedness of Others," discussed in Subsection 25.8(k), provides further guidance on accounting for and disclosure of guarantee obligations.

SEC Codification of Financial Reporting Policies Sec. 104 points out that oral guarantees, even if legally unenforceable, may have the same financial reporting significance as written guarantees.

In accordance with APB Opinion No. 28, "Interim Financial Reporting," contingencies and other uncertainties that could be expected to affect the fairness of presentation of financial data at an interim date should be disclosed in interim reports in the same manner required for annual reports. Such disclosures should be repeated in interim and annual reports until the contingencies have been removed, resolved, or become immaterial.

Financial statements sometimes contain a contingency conclusion that addresses the estimated total unrecognized exposure to one or more loss contingencies. It may state, for example, that "management believes that the outcome of these uncertainties should not have (or 'may have') a material adverse effect on the financial condition, cash flows, or operating results of the enterprise." Alternatively, the disclosure may indicate that the adverse effect could be material to a particular financial statement or to results and cash flows of a quarterly or annual reporting period. AICPA Statement of Position (SOP) 96-1, "Environmental Remediation Liabilities," states the following about contingency conclusions:

Although potentially useful information, these conclusions are not a substitute for the required disclosures of ... FASB Statement No. 5, such as [its] requirement to disclose the amounts of material reasonably possible additional losses or to state that such an estimate cannot be made. Also, the assertion that the outcome should not have a material adverse effect must be supportable. If an entity is unable to estimate the maximum end of the range of possible outcomes, it may be difficult to support an assertion that the outcome should not have a material adverse effect.

AICPA SOP 94-6, "Disclosure of Certain Significant Risks and Uncertainties," requires disclosure about significant estimates used to determine the carrying amounts of assets or liabilities and the disclosure of gain or loss contingencies if (1) it is at least reasonably possible that the estimate of the effect on the financial statements of a set of circumstances that existed at the financial statement date will change in the near term due to one or more future confirming events and (2) the effect of the change would be material. Near term is a period not to exceed one year from the date of the financial statements. Disclosure requirements include the nature of the uncertainty and an indication that it is at least reasonably possible that a material change will occur in the near term. Disclosure of factors causing the uncertainty is encouraged but not required. If an uncertainty is a loss contingency under Statement No. 5, disclosure must also provide an estimate of the possible loss or range of loss. If the SOP's disclosure criteria are not met as a result of the use of risk-reduction techniques, the disclosures that would otherwise be required by the SOP and disclosure of the risk-reduction techniques are encouraged but not required.

Examples of estimates subject to change in the near term include litigation-related obligations, contingent liabilities for guarantees of other entities, and amounts reported for pensions and other benefits.

Enterprises may decide to insure against certain risks by specifically obtaining coverage. In other cases risks may be borne by the company either through use of deductible clauses in insurance contracts or by not purchasing insurance at all. Insurance policies purchased from a subsidiary or investee, to the extent that policies have not been reinsured with an independent insurer, are considered not to constitute insurance. Some risks, such as a decline in business, may not be insurable.

FASB Statement No. 5 states that the absence of insurance does not mean that an asset has been impaired or that a liability has been incurred at the date of the enterprise's financial statements. Therefore, exposure to uninsured risks does not constitute a contingency requiring either disclosure or accrual. However, Statement No. 5 does not discourage disclosure of noninsurance or underinsurance in appropriate circumstances, and such disclosure may be necessary, for example, because the noninsurance or underinsurance violates a debt covenant.

If an event has occurred, such as an accident, for which the enterprise is not insured and for which some liability is suggested, the proper accounting or disclosure of that event must be considered within the framework of the standard.

Accounting for and disclosure of litigation, claims, and assessments, either actual or possible, often presents problems. Those problems may involve the probability of payment, estimates of amounts, and, in a particularly sensitive area, the reluctance of companies to disclose information that may be actually or potentially adverse. Full disclosure or the accrual of a loss contingency, when litigation is threatening or pending, may well be seized on by the opposing party as evidence to support its case.

FASB Statement No. 5 does not exempt from its accounting or disclosure provisions entities that believe complying with those provisions could damage their position in litigation. If the underlying cause of the litigation, claim, or assessment is an event occurring before the date of the financial statements, the probability of an unfavorable outcome must be assessed to determine whether it is probable a liability has been incurred. Among the factors that should be considered are the nature of the litigation, claim, or assessment, the progress of the case (including progress after the date of the financial statements but before those statements are issued), the opinions or views of legal counsel and other advisers, the company's experience in similar cases, the experience of other companies in similar cases, and any decision of the company's management as to how the company intends to respond to the lawsuit, claim, or assessment (e.g., a decision to contest the case vigorously or a decision to seek an out-of-court settlement). The fact that legal counsel is unable to express an opinion that the outcome will be favorable should not necessarily be interpreted to mean that a loss is probable.

Among the most difficult issues to resolve is that of unasserted claims. An unasserted claim exists, for example, when the company knows that an event such as a product failure has occurred, but no actions have yet been brought against the company. It is conceivable that disclosure of the event, along with a discussion indicating the possibility of claims being asserted, could trigger litigation adverse to the company that might not have been brought in the absence of the company's own disclosure. FASB Statement No. 5 states that a judgment must first be made as to whether the assertion of a claim is probable. If the judgment is that assertion is not probable, no accrual or disclosure would be required. If, however, the judgment is that assertion is probable, a second judgment must be made as to the degree of probability of an unfavorable outcome.

For both asserted and unasserted litigation, claims, and assessments, if an unfavorable outcome is determined to be probable and the amount of loss is reasonably estimable, the loss should be accrued. If an unfavorable outcome is determined to be reasonably possible but not probable, or if the amount of loss cannot be reasonably estimated, a loss should not be accrued, but the disclosures required for other contingencies would be required.

Caution should be used in disclosing "contingency conclusions" (discussed in Section 25.3). In at least one case, a disclosure to the effect that the outcome of litigation should not have a material adverse effect on the financial condition, cash flows, or operating results of the enterprise was the basis for the awarding by a jury of punitive damages well in excess of those originally sought in a lawsuit.

In the past, some companies have provided, sometimes through income, reserves for general contingencies. In other cases, such reserves have been established as appropriations of retained earnings. FASB Statement No. 5 does not permit such general contingency reserves to be charged to income. Appropriation of retained earnings is not prohibited provided that it is shown within the stockholders' equity section of the balance sheet and is clearly identified as an appropriation of retained earnings.

The obligation to satisfy a product warranty, incurred in connection with the sale of goods or services, is a loss contingency of the kind that requires accrual under FASB Statement No. 5. That is, future obligations under warranties should be estimated and provided for. Such estimates may be difficult, particularly if new products or changed warranty terms are involved. Still, an effort should be made to determine the liability. If necessary, reference may be made to the experiences of other companies.

If there is inadequate information to permit a reasonable estimate of the obligation for warranties, the propriety of recording a sale of the goods until the warranty period has expired should be questioned.

SOP 96-1, "Environmental Remediation Liabilities," provides accounting guidance on environmental remediation liabilities that relate to pollution arising from some past act. The SOP states that such liabilities should be accrued when the criteria of FASB Statement No. 5 are met, and it includes benchmarks to aid in determining when environmental liabilities should be recognized.

The SOP establishes a presumption that, given the legal framework within which most environmental remediation liabilities arise, (1) if litigation has commenced or a claim or assessment has been asserted or if commencement of litigation or assertion of a claim or assessment is probable and (2) if the company is associated with the site—that is, if it in fact arranged for the disposal of hazardous substances found at a site or transported hazardous substances to the site or is the current or previous owner or operator of the site—the outcome of such litigation, claim, or assessment will be unfavorable.

The estimate of the liability should include (1) the entity's allocable share of the liability for a specific site and (2) the entity's share of amounts related to the site that will not be paid by other potentially responsible parties or the government.

Costs to be included in the measurement of the liability include:

Incremental direct costs of the remediation effort

Costs of compensation and benefits for those employees who are expected to devote a significant amount of time directly to the remediation effort, to the extent of that amount of time

The measurement of the liability should be based on enacted laws and existing regulations and policies—no changes in regulations or policies should be anticipated. The measurement of the liability should be based on the reporting entity's estimate of what it will cost to perform all elements of the remediation effort when they are expected to be performed, using remediation technology that is expected to be approved to complete the remediation effort. The measurement of the liability, or of a component of the liability, may be discounted to reflect the time value of money if the aggregate amount of the liability or component of the liability and the amount and timing of cash payments for the liability or component are fixed or reliably determinable.

The SOP provides financial statement display guidance and encourages, but does not require, a number of disclosures that are incremental to the FASB Statement No. 5 and SOP 94-6 requirements.

For SEC registrants, SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin (SAB) No. 92, "Accounting and Disclosures Relating to Loss Contingencies," provides additional accounting, display, and disclosure guidance concerning environmental liabilities. SAB No. 92 also states that the staff would not object to a registrant accruing site restoration, postclosure and monitoring, or other environmental exit costs that are expected to be incurred if that is established accounting practice in the registrant's industry. In other industries, the staff would raise no objection provided that the liability is probable and reasonably estimable. If the use of an asset in operations gives rise to growing exit costs that represent a probable liability, the accrual of the liability should be recognized as an expense in accordance with the consensus in EITF Issue No. 90-8, "Capitalization of Costs to Treat Environmental Contamination."

Vulnerability due to concentrations arises because of exposure to risk of loss greater than an enterprise would have had if it mitigated its risk through diversification. Although an exposure to risk from a concentration is not the same as a liability, the subject is included in this chapter because it tends to be associated with the subject of liabilities.

SOP 94-6 requires disclosure of the following kinds of concentrations:

Concentrations in volume of business with a particular customer, supplier, lender, grantor, or contributor

Concentrations in revenue from particular products, services, or fund-raising events

Concentrations in available sources of supply of materials, labor or services, or licenses or other rights used in operations

Concentrations in the market or geographic area in which the entity operates

Disclosure is required if all of the following conditions are met:

The concentration exists at the balance sheet date.

The enterprise is vulnerable to a near-term severe impact as a result of the concentration.

It is at least reasonably possible that the events that could cause the severe impact will occur in the near term.

Severe impact, which is defined as a significant financially disruptive effect on the normal functioning of the entity, is a higher threshold than material, but the concept includes matters that are less than catastrophic, such as those that would result in bankruptcy.

The disclosure requirements also apply to group concentrations, which may arise if a number of counterparties or items have similar economic characteristics.

Although other kinds of concentrations may create equal, or even greater, vulnerability, they are not covered by the SOP for practical reasons. For example, a business's dependence on key management personnel might make it vulnerable to a severe impact in the event of the loss of those persons' services. However, a requirement to disclose that the occurrence of an adverse effect of that vulnerability is reasonably possible in the near term might violate accepted rights to privacy, for example, by causing information about an individual's health or marital problems to be revealed, and place an unreasonable burden on the accountant to know that information.

Disclosure should include information that is adequate to inform users of the general nature of the risk associated with the concentration. For labor subject to collective bargaining agreements meeting the disclosure requirements, the notes should include the percent of the labor force covered by collective bargaining agreements and the percent of the labor force covered by agreements that will expire within one year. For operations outside the home country, the disclosures should include the carrying amount of net assets and geographical areas in which the assets are located.

An entity's commitment to a plan to exit an activity, by itself, does not create a present obligation to others that meets the definition of a liability. FASB Statement No. 146, "Accounting for Exit or Disposal Activities," requires recognition of a liability for costs associated with an exit or disposal activity when a liability has been incurred, and points out that a liability is not incurred until a transaction or event occurs that leaves an entity with little or no discretion to avoid the future transfer or use of assets to settle the liability.

Under FASB Statement No. 146, a one-time benefit arrangement exists at the date the plan of termination meets all of the following criteria and has been communicated to employees:

Management, having the relevant authority to approve the action, commits to a plan of termination.

The plan identifies the number of employees to be terminated, their job classifications or functions and their locations, and the expected completion date.

The plan establishes the terms of the benefit arrangement, including the benefits that employees will receive upon termination, in sufficient detail to enable employees to determine the kind and amount of benefits they will receive if they are involuntarily terminated.

Actions required to complete the plan indicate that it is unlikely that significant changes to the plan will be made or that the plan will be withdrawn.

The timing of recognition of and measurement of a liability for one-time termination benefits depends on whether employees are required to render service until they are terminated in order to receive the termination benefits and, if so, whether they will be retained beyond the minimum retention period. If employees are not required to render service until they are terminated (i.e., if employees are entitled to receive the termination benefits regardless of when they leave) or if they will not be retained to render service beyond the minimum retention period, a liability is recognized and measured at fair value at the date the plan of termination has been communicated to the employees (referred to as the communication date).

If employees are required to render service until they are terminated in order to receive termination benefits and will be retained to render service beyond the minimum retention period, a liability for termination benefits is measured initially at the communication date based on the fair value of the liability as of the termination date. The liability should be recognized ratably over the future service period. Any change resulting from a revision to either the timing or the amount of estimated cash flows over the future service period should be measured using the credit-adjusted risk-free rate that was used to measure the liability initially, and the cumulative effect of the change should be recognized as an adjustment to the liability in the period of the change.

If a plan of termination changes and employees who were expected to be terminated within the minimum retention period are retained beyond that period, a liability previously recognized at the communication date should be adjusted to the amount that would have been recognized had the employees originally been expected to render service beyond the minimum retention period. The cumulative effect of the change should be recognized as an adjustment of the liability in the period of the change.

If a plan of termination includes both involuntary termination benefits and termination benefits offered for a short period in exchange for employees' voluntary termination of service, a liability for the involuntary termination benefits should be recognized in accordance with Statement No. 146 and a liability for the excess of the voluntary termination benefit amount over the involuntary termination benefit amount should be recognized in accordance with FASB Statement No. 88, "Employers' Accounting for Settlements and Curtailments of Defined Benefit Pension Plans and for Termination Benefits."

A liability for costs to terminate, in connection with an exit activity, an operating lease or other contract before the end of its term should be recognized and measured at its fair value when the entity terminates the contract in accordance with the contract terms (e.g., by giving written notice or otherwise negotiating a termination with the lessor). No liability for contract termination costs may be recognized solely because of an entity's commitment to an exit or disposal plan. The termination of a capital lease should be accounted for in accordance with FASB Statement No. 13, "Accounting for Leases."

A liability for costs that will continue to be incurred under a contract for its remaining term without economic benefit should be recognized and measured at its fair value when the entity ceases using the right conveyed by the contract (referred to as the cease-use date). If the contract is an operating lease, the fair value of the liability at the cease-use date is determined based on the remaining lease rentals, reduced by estimated sublease rentals that could reasonably be obtained for the property, even if the entity does not intend to sublease. Remaining rentals may not be an amount less than zero.

A liability for other costs associated with an exit or disposal activity, such as costs to consolidate or close facilities and relocate employees, should be recognized and measured at its fair value in the period in which the liability is incurred, which is generally when goods or services associated with the activity are received. No liability should be recognized before it is incurred, even if the costs are incremental to other operating costs and will be incurred as a direct result of a plan.

Costs associated with an exit or disposal activity should be included either in income from continuing operations before income taxes or in results of discontinued operations, depending on whether the exit or disposal activity involves a discontinued operation. If an exit or disposal activity does not involve a discontinued operation, the costs may not be presented in the income statement net of taxes or in any manner that implies they are similar to an extraordinary item.

If an entity's responsibility to settle a liability for a cost associated with an exit or disposal activity recognized in a prior period is discharged or removed, the liability should be reversed and the costs should be reversed through the same income statement line items used when the costs were recognized initially.

FASB Statement No. 146 requires disclosure of the following information in the period in which an exit or disposal activity is initiated and any subsequent period until the activity is completed:

A description of the exit or disposal activity, including the facts and circumstances leading to the expected activity and the expected completion date

For each major kind of cost associated with the activity (e.g., one-time termination benefits, contract termination costs, and other associated costs)

The total amount expected to be incurred in connection with the activity, the amount incurred in the period, and the cumulative amount incurred to date

A reconciliation of the beginning and ending liability balances showing separately the changes during the period attributable to costs incurred and charged to expense, costs paid or otherwise settled, and any adjustments to the liability with an explanation of the reasons therefore

The line item(s) in the income statement or the statement of activities in which the cost in the second bullet above are aggregated

For each reportable segment, the total amount of costs expected to be incurred in connection with the activity, the amount incurred in the period, and the cumulative amount incurred to date, net of any adjustments to the liability with an explanation of the reasons therefore

If a liability for a cost associated with an activity is not recognized because fair value cannot be reasonably estimated, that fact and the reasons therefore

When a domestic corporation consolidates a foreign branch or subsidiary or when an importer purchases goods or incurs liabilities expressed in foreign currencies, the problem arises of translating the liabilities into U.S. dollar amounts. Accounting principles in this area have undergone considerable change in recent years and are discussed in Chapter 13.

As indicated previously, obligations expected to be liquidated within the next operating cycle by the use of current assets or the creation of other current obligations should be classified as current liabilities.

The SEC [Regulation S-X, Rule 5.02(19)] requires the following classification in balance sheets:

Accounts and notes payable. State separately amounts payable to:

Banks for borrowings

Factors or other financial institutions for borrowings

Holders of commercial paper

Trade creditors

Related parties

Underwriters promoters, and employees (other than related parties)

Others

Rule 5.02(19) also requires disclosure of the amount and terms of unused lines of credit for short-term financing.

Regulation S-X, Rule 5.02(20), requires the separate statement in the balance sheet or in a note thereto of any item in excess of five percent of total current liabilities. Such items may include, but are not limited to, accrued payrolls, accrued interest, taxes, indicating the current portion of deferred income taxes, and the current portion of long-term debt. Remaining items may be shown in one amount.

Figure 25.1. Sample presentation of short-term liabilities as required by the SEC. (Source: Oklahoma Gas & Electric Co., 1988 Annual 10K Report.)

Many companies disclose arrangements for compensating balances in the note covering short-term debt, although these are covered in Regulation S-X under requirements related to cash.

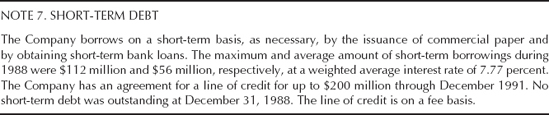

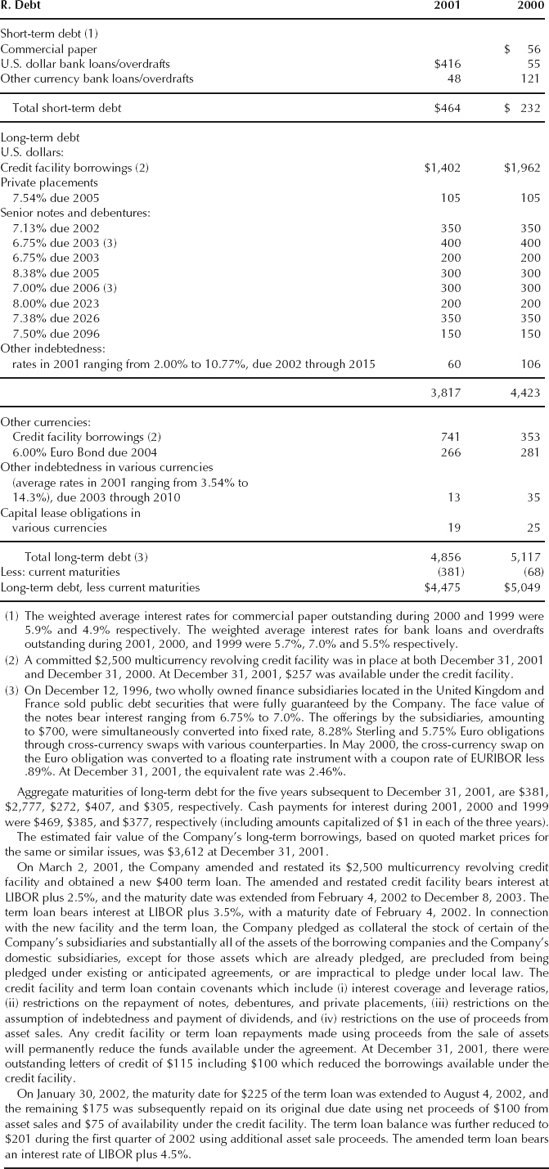

An example of a note that presents the required SEC information is given in Exhibit 25.1.

In the less detailed form used in published reports to shareholders, it is common to present current liabilities as follows:

Payable to banks

Accounts payable and accrued expenses

Federal income taxes payable

Current portion of long-term debt

As a general rule, current liabilities should not be offset against related assets. For example, an overdraft at one bank should not be canceled against a debit balance at another bank; such offsetting distorts the current ratio. An exception to the general rule is indicated by APB Opinion No. 10, Omnibus Opinion—1966, in the instance of short-term government securities "when it is clear that a purchase of securities (acceptable for the payment of taxes) is in substance an advance payment of taxes that will be payable in the relatively near future...."

Supplemental disclosure should be used to indicate partially and fully secured current claims, overdue payments, and special conditions of future payment [see Subsection 25.1(b)].

Bonds are essentially long-term notes issued under a formal legal procedure and secured either by the pledge of specific properties or revenues or by the general credit of the issuer. In the last case, the bonds are considered "unsecured." The most common bonds are those issued by corporations, governments, and governmental agencies. A significant difference, from the viewpoint of the holder although not the issuer, is that most obligations of state and local governmental units are free of federal income taxes on interest and sometimes of state taxes, as well. Both state and local government bonds are usually called municipals. Agency bonds are obligations of government agencies and frequently carry a form of guarantee from the government unit. The typical bond contract, known as an indenture, calls for a series of "interest" payments semiannually and payment of principal or face amount at maturity. Bonds differ from individual notes in that they represent fractional shares of participation in a group contract, under which a trustee acts as intermediary between the corporation and holders of the bonds. The terms are set forth in the trust indenture covering the entire issue. Indentures are frequently long and complex documents and normally contain various conditions and restrictions related to the operations of the borrower.

The conditions and restrictions referred to as covenants may include restrictions on dividend payments and an agreement to maintain a minimum amount of working capital. Failure to comply with covenants would lead to default and acceleration of the due date of the debt. This event may trigger default on other obligations of the corporation under cross-covenant provisions.