HIRE FOR CHARACTER, TRAIN FOR COMPETENCE

No matter what the job is, its description focuses on two things: what the employee needs to know, and what the employee needs to do. Knowledge and skill are essential qualities in any employee. But are they enough? Isn’t there another aspect of a job candidate’s profile that is at least as important as knowledge and skill—namely, that person’s character?1

—BRUCE WEINSTEIN

Hiring an impressive résumé seems like a good bet. We give the benefit-of-the-doubt status to those who have completed exclusive educations and who have worked for name brand organizations. Credentials and competencies are certainly important considerations when someone is being hired or promoted. So is character, which is why it is useful to understand how a candidate responds to a difficult teammate, customer, partner, patient, or student. It would be revealing to learn how someone performed when no one was looking. It is relevant to learn how someone performed doing work that was hard and important. In other words, there is the person we say we are when the sea is calm, and there is the person we really are during a storm.

Besides, consider the amount of wasted energy caused when character is missing in action. Despite the disproportionate impact of low character on performance, we might overlook this limitation for people with high competence. Examples: the very productive salesman who harasses people around him; the skilled, productive surgeon who has outbursts and throws scalpels in the operating room. Our admonition is to resist this temptation. Hire for character and train for competence.

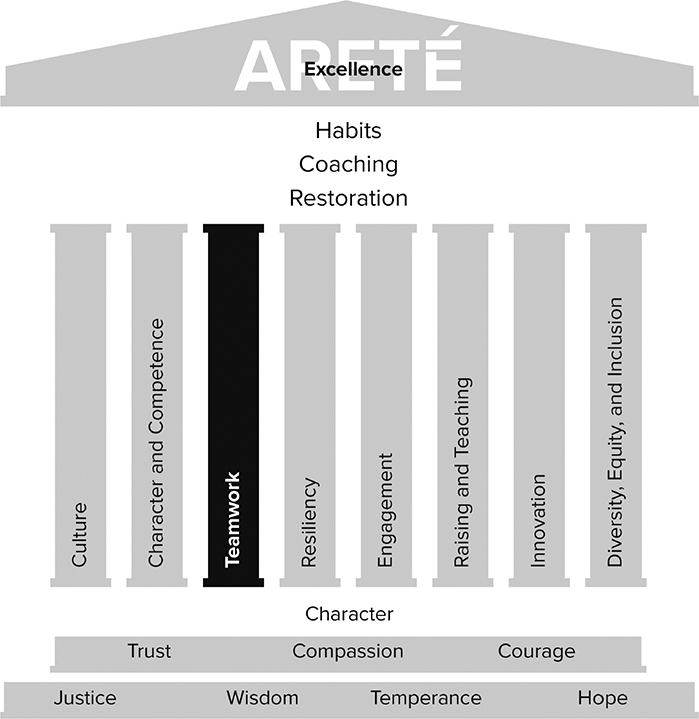

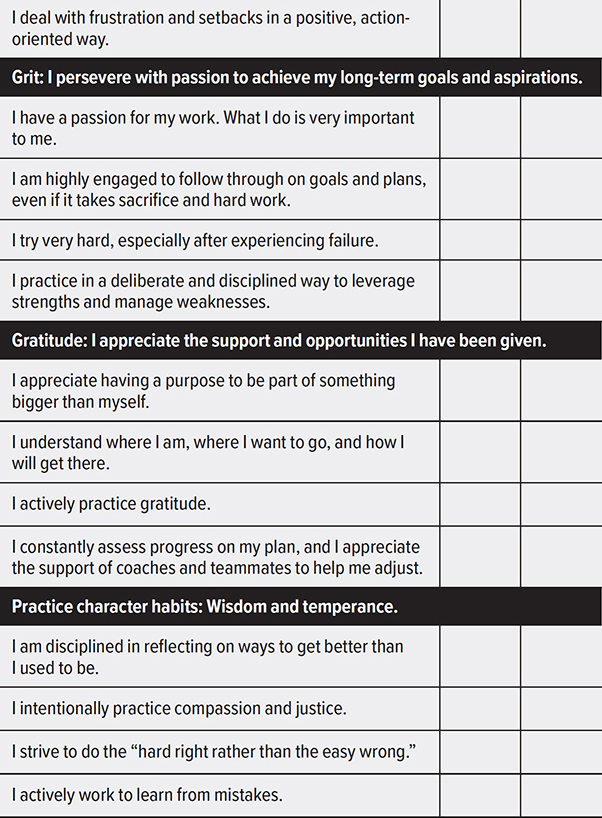

Arguably, the most powerful way to build a culture of better humans and better performers is through rigorous assessment of who comes through the front door (new hires); who gets to sit in the corner office (promotions); and who is shown the door (separations). Where do you start? “Who Before What.” That is a phrase that Jim Collins coined to describe the first necessary stage to building a great company.2 Who we are defines our character. What we do defines our competence (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 “Who Before What”

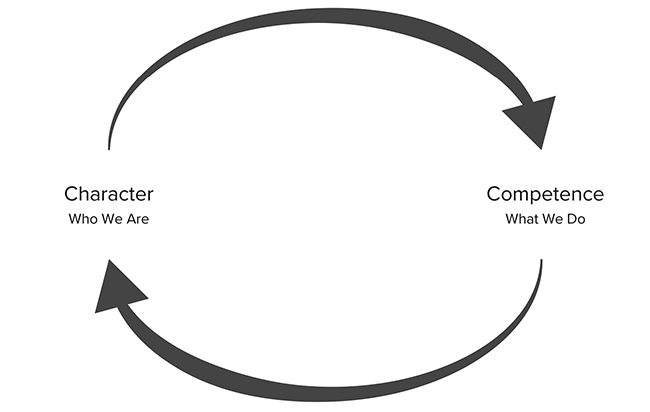

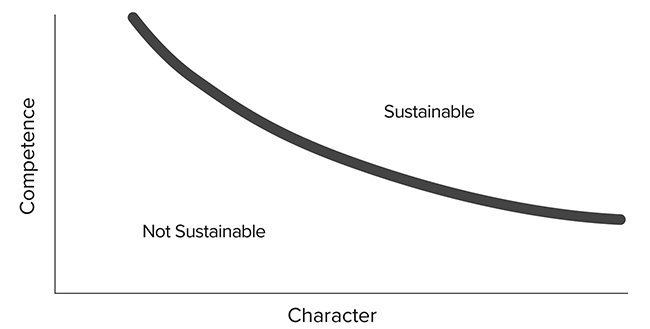

Character and competence can’t be defined as either you have it or you don’t. Certainly no one can claim they are completely virtuous. And even the most dismal among us have some redeeming character qualities. Similarly, no one can claim they are completely competent as a physician, engineer, carpenter, or student. Figure 4.2 demonstrates when it comes to character and competence, we need to be more nuanced than either/or thinking. We can think of both qualities existing along a sliding scale that when both character and competence are strong, the result is sustainable high performance. In contrast, when competence and/or character are inadequate, then high performance isn’t sustainable.

Figure 4.2 Sliding Scale for Competence and Character

Hiring for character and training for competence certainly doesn’t mean ignoring incompetence. Perhaps evaluating whether the person has the educational background, professional experience, and knowledge and skills to do the job is the place to start. After all, a well-intentioned incompetent can cause plenty of grief no matter how high their character.

At the same time, there are important performance reasons to give significant weight to character. Character is a performance amplifier of competence. Character is malleable and can be developed. Character enables people to deliver sustainable performance during periods of uncertainty, adversity, and pressure. High-character people by definition are committed to grow and develop continually.

Despite the performance reasons for considering character, often competence is given more weight. This isn’t because character is viewed as unimportant. It is because those making hiring decisions are unaware of the performance benefits of character or how character can be evaluated.

Figure 4.3 presents four quadrants that can be used to evaluate teammates on the character and competence continua. The easy decisions relate to keepers of the culture and poor performers. You are glad to have one on your team, and you plan to remove the other. The real test of what truly defines the culture is how we treat potentials and culture killers:

Figure 4.3 Character and Competence as Determinants of Performance

Keepers of the culture: Teammates who are high in competence and character define the culture at its best. They achieve the right results, the right way, for the right reasons. They seek advice and feedback about how to get even better. These are people you should drive to work each day! Ask them what they need and support them.

Poor performers: Someone who is low in character and competence reflects a selection error. People certainly can change, though no organization wants to see anyone in this quadrant. How one offboards these individuals also speaks to the culture. This should be done with grace and consideration, while maintaining rigor about the need for performance and character. Offboarding should in no way be a demeaning process but rather simply a recognition of poor fit with the organization’s culture and goals.

Potentials: Employees in this quadrant have high levels of character but lower levels of competence. Clearly, some threshold of competency is necessary, though few candidates tick every professional and educational box deemed essential to succeed at the next level. Potentials are usually good bets because people of character by definition are motivated to become more competent.

Culture killers: Leaders in this quadrant are an organization’s worst nightmare. They achieve results through fear and blame rather than engagement and teamwork. They may not break laws, but they surely break trust, increase cynicism, and decrease engagement. When people lack character, you’d prefer they were dumb and lazy, so at least you could see it coming. Being cunning, clever, and competent is a deadly combination to an organization. While it is tempting to put up with toxic leaders who pay the bills or surgeons who are surgically brilliant but who throw scalpels, doing so has tremendous adverse consequences for the organization. Retaining “culture killers” teaches everyone that while integrity may be good, financial results are better. Rather, culture killers need attention and prompt organizational action including separation if there is no commitment to improve.

PERFORMANCE VIRTUES

Nobel Prize–winning economist James Heckman demonstrated that noncognitive factors such as social skills, motivation, and persistence have a bigger payoff in the labor market and in school than achievement tests. Heckman reviewed numerous studies that demonstrate that high IQ people fail to achieve for noncognitive reasons.

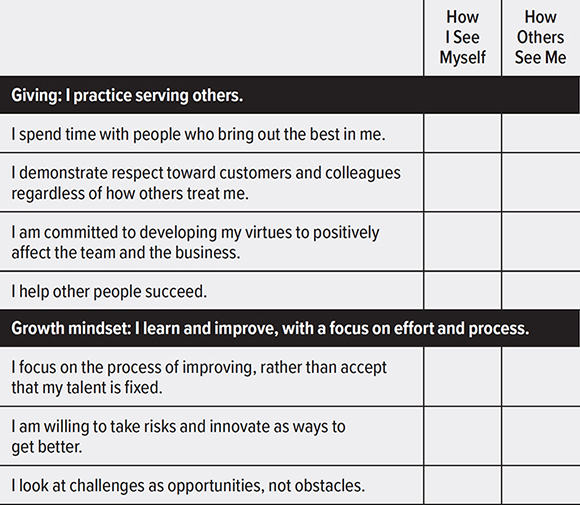

Consider the adage, “People are hired on their competencies and fired on their character.” Similarly, lower IQ people can succeed for noncognitive reasons. While cognitive abilities are largely formed early in life, noncognitive skills continue to develop throughout our life.3 So, if you are convinced that hiring for character is an especially sound strategy for strengthening a culture, but don’t know what to look for in candidates, consider the performance virtues that we call the 4Gs: giving, gratitude, growth mindset, and grit.

Giving and How to Spot It

Every day, people make decisions whether to act like givers, matchers, or takers, which author Adam Grant defines in this way:

Givers: Help others unconditionally. They prefer to give more than they get.

Matchers: Help conditionally. I’ll scratch your back if you scratch mine. Most people are matchers.

Takers: Will help only if they get something out of it. They are more interested in getting credit than helping.4

When it comes to performance, whom would you bet on: the givers, the matchers, or the takers? For example, if you have a team of salespeople, who sells more? If you have surgeons, who has the fewest medical errors? The answer: in the short term, taking works. The problem is that once people catch on to your taking, at best they stop helping and at worst, they sabotage your efforts. It’s the givers who are both the best performers and the worst performers. For givers to succeed and be the best performers, they must avoid being doormats, especially when they go up against takers. That said, takers are the culture killers that have a disproportionate negative impact on performance. One taker can drag the matchers down to takers and the givers down to matchers.5 If takers don’t change, then—as with culture killers—what we tolerate is what we get. Sometimes we need to say to a taker—as we say to a culture killer—“We love you, but you need to leave now.”

Look for individuals who share knowledge and help and who contribute to others without seeking anything in return. While takers tend to use “I,” “me,” and “my” pronouns and take personal credit, givers are more likely to use “we,” “our,” and “us” pronouns and share achievement. Takers can describe their own achievements. Takers struggle with how they contributed to other people’s achievements. When takers talk about mistakes, they usually blame others, whereas givers own their mistakes and share what they learned. Givers help others achieve their goals, which lies at the heart of effective collaboration, innovation, quality improvement, and service excellence. Giving and generosity have one thing in common: being other focused.

Gratitude and How to Spot It

Gratitude gives us or others hope. Cicero said, “Gratitude is not only the greatest of the virtues, but the parent of all the others.”6 A few decades ago, science caught up to this ancient wisdom by running an experiment. One group wrote down three things that ticked them off for 21 consecutive days; the other group wrote down three things for which they were grateful for 21 consecutive days, and the third group did nothing. The results of the study were as you would expect. The miserable group was more miserable on day 22 than on day 1. The grateful group was more grateful on day 22 than on day 1. And the control group experienced no difference.

Appreciation or gratitude inspires engagement more than higher pay, promotions, empowerment, or training.

When people receive thanks for their generosity, they are more likely to continue giving, helping, cooperating, and collaborating. People who experience gratitude in their work are less likely to experience burnout and more likely to experience satisfaction in their work.7

Grateful people are humble, self-aware, and wise. They know that success is seldom achieved solely by one’s own effort. For this reason, they share achievement rather than take credit. They live a reflective, intentional, and self-disciplined life, seeking the positives in all situations.

Grateful people value ethics and honesty. They want to do business in a way that promotes healthy work relationships and that also promotes the quality and safety of the products and services they create. Grateful people are more resilient, flexible, and better team players than people who lack gratitude. Look for evidence of a “Pay it forward” or “We’re all in this together” mentality.8

Growth Mindset and How to Spot It

As Carol Dweck’s research demonstrates, people with a “growth mindset” believe you can get better, smarter, and more collaborative. People with a growth mindset seek out challenges so they can grow. “Fixed mindset” people believe that you either have ability or you don’t, so they avoid challenges.

Dweck offers some myth busters through her research. First, being flexible, being open-minded, and having a positive outlook are all laudable, but absent behaviors that lead to actual improvement, this is what she calls a “false growth mindset.” In reality, we all are a mixed bag of fixed and growth mindsets because no person or species has a “pure growth mindset.” Second, praising and rewarding effort are only a part of developing a growth mindset. Results matter. Adopting a “not-yet strategy” means that we haven’t yet achieved results. “Not yet” means that we will keep trying, keep learning, and keep seeking feedback in order to ultimately achieve the desired results. Having a persistent not-yet mindset will lead to better results.9

It is incredibly challenging to acquire a growth mindset because we all exhibit both the insecurity and defensiveness that can shut down a growth mindset. When competition is a zero-sum game, sharing, collaborating, seeking feedback, and admitting mistakes can come to a screeching halt. When we activate our fixed mindset, defined as becoming defensive or scared, that is the time we most need to kick a growth mindset into gear.10

Here’s an example of a growth mindset. Dweck was retained to help a professional sports team develop interview screening questions for prospective draft choices. Her suggestion was simple. Ask the candidates: “What do you expect at the next level of competition, and how do you prepare to improve?” Years of research have shown that we are not good at predicting future success on the basis of current talent assessments. Why? Because current assessments do not reveal people’s future growth potential and how they might perform with the right support, commitment, effort, and training. In fact, research shows that people’s level of support, commitment, effort, and continued training is what eventually separates the most successful people from their equally talented, but less successful peers.11

Grit and How to Spot It

Author and University of Pennsylvania Professor Angela Duckworth has defined grit as “perseverance and passion for long-term goals.”12 In fact, grit involves working hard for years to achieve a goal. Yet things get in our way. For example, as an automatic response to perceived or real danger, we tend to invest more in fear than hope. Yet, the primordial part of our brain does a lousy job distinguishing between small stuff and really big stuff, like the difference between getting our feelings bruised in a meeting because our idea wasn’t accepted versus experiencing a serious physical threat.

The Giraffe Heroes Project provides an interesting way to cultivate grit. This international organization identifies largely unknown compassionate risk-takers who stick their necks out for the common good. For example, Joe Medalia uses his business to train dozens of youngsters with disabilities despite the time and cost of correcting errors. Medalia actively pushes other business owners to do the same. The Giraffe organization’s strategy involves participants’ listening and reading stories about others who have exhibited courage and then the participants’ telling their own stories about courageous people they know.

We learn to “stick our neck out” by taking on problems that are sitting under our nose. For example, strive to be courageous by identifying a need in your community and contribute to solutions.13

HOW TO COMBAT BIAS

Anyone who has been involved in hiring decisions should be humbled by how poorly interviews predict future performance. What would organizations discover if a year after hiring decisions were made, they evaluated how many teammates were disappointments or diamonds in the rough? We filter information and make quick hiring decisions based more on confirmation bias than we may realize. Research has revealed that who gets hired has more to do with the interviewer than with the interviewee. We tend to hire people who are more like us rather than what the team or business needs. To make matters worse, it is easy to evaluate what matters least (education, grades, or age) but not what matters most (the 4Gs). There are two important ways to mitigate these hiring risks: conducting structured interviews and having multiple assessors.

First, put together a diverse hiring team, and make sure to compare evaluations. That simple step helps overcome bias. Second, structure the interviews because doing so increases the chances of making good hiring decisions. Using structured interviews means that all evaluators will be looking for the same evidence-based performance virtues—giving, gratitude, growth mindset, and grit—and asking the same questions. Then all evaluators can share notes with each other, so that everyone can assess the candidates from multiple perspectives using the same criteria. Here are sample questions to help create structured interviews:

![]() Tell us about a time your behavior had a positive impact on your team. (Follow-ups: What was your primary goal and why? How did your teammates respond? How do you see yourself contributing to teamwork if you join our organization?)

Tell us about a time your behavior had a positive impact on your team. (Follow-ups: What was your primary goal and why? How did your teammates respond? How do you see yourself contributing to teamwork if you join our organization?)

![]() Tell us about a time when you effectively managed your team to achieve a goal. What did your approach look like? (Follow-ups: What were your targets, and how did you meet them as an individual and as a team? How did you adapt your leadership approach to different individuals? What was the key takeaway from that specific situation?)

Tell us about a time when you effectively managed your team to achieve a goal. What did your approach look like? (Follow-ups: What were your targets, and how did you meet them as an individual and as a team? How did you adapt your leadership approach to different individuals? What was the key takeaway from that specific situation?)

![]() Tell us about a time you had difficulty working with someone (can be a coworker, classmate, or client). What made this person difficult to work with for you? (Follow-ups: What steps did you take to resolve the problem? What was the outcome? What could you have done differently?)

Tell us about a time you had difficulty working with someone (can be a coworker, classmate, or client). What made this person difficult to work with for you? (Follow-ups: What steps did you take to resolve the problem? What was the outcome? What could you have done differently?)

![]() Tell us about a time when you faced personal or professional adversity. (Follow-ups: How did you respond? What did you learn from the experience? How did you grow?)

Tell us about a time when you faced personal or professional adversity. (Follow-ups: How did you respond? What did you learn from the experience? How did you grow?)

![]() Tell us about a person who had a significant positive impact on you. (Follow-ups: What did that person teach you? How did they help you grow?)

Tell us about a person who had a significant positive impact on you. (Follow-ups: What did that person teach you? How did they help you grow?)

Structured interviews conducted by a diverse hiring team are more fair than unstructured interviews conducted by a homogenous team. As a result, candidates report a better interviewing experience. However, the cautionary note is that the 4Gs are easier to observe when we see how someone responds to stress, failure, and working in teams and harder to predict during an interview. With that caution in mind, let’s shift from how to select people to how to develop people.

THE IMPORTANCE OF INTERIOR DEVELOPMENT

External development can be seen—impressive job titles, big house, nice car, and expensive vacations—while internal development is often “hidden in full view.” When it comes to internal development, we learn to give, to develop grit, to develop a growth mindset, and to be grateful. And we also learn to take, to quit, to have a fixed mindset, and to be ungrateful. A freshly minted college graduate put it this way: “I have always been goal directed with the aim to build my engineering credentials. After attending a session on the importance of practicing virtues, I want to pay more attention to the kind of person I want to be.” The virtues and the 4Gs offered her an operating model to do just that.

Given the personal and professional importance of the 4Gs, how do people seek feedback about their strengths and where they can improve? Most people want feedback. Too few know how to seek feedback. Too many wait passively to receive it.

One of the reasons seeking feedback is a challenge is that it sits between our drive to learn and our desire to belong.

There are ways to both learn and cultivate our sense of belonging. One way is to start a “50 cups of coffee” learning tour by identifying 50 people a year whom you want to learn from. Request 20 to 30 minutes from each of them to learn something specific. If they have observed your performance, perhaps you will ask for feedback about a project they watched you lead. Or you might ask them questions about building strong teams, how they prepare for presentations, or insights about their career path. The Honor Foundation proposes this goal to military special operatives who are transitioning into civilian life. However, a 50 cups of coffee tour doesn’t have to be limited to making a career transition. It can be an ongoing way to make connections and learn.