We are finished considering what digital innovation you’ve made, how we process it psychologically, and why someone might recommend it to us; now we examine who recommended it to us and how that affects our receptivity. Don’t think for a minute that we adopt every meme that is recommended to us. Even the memes that are privileged enough to be promoted must pass through another social bottleneck: they must be recommended by a person or a group who is actually influential over our behavior.

The established field of social influence theorytells us that we will be more receptive to your meme if it is recommended by…

Three of our peers (no fewer will suffice, no more are necessary)

Whose motives cannot be discounted by self-interest

And who are friends of our friends or enemies of our enemies

The first factor that determines our receptivity to your meme is the count of our peers who are receptive themselves. They may recommend your meme actively, or we may merely become aware that they have adopted it. When we do, we inch closer to doing so ourselves. Think back to the last tech device you adopted, be it your smartphone , tablet, hybrid car, or wearable. Quite likely, when you learned that one peer had bought one, this wasn’t enough to get you to do so too. But when two peers adopted it, you drew measurably closer to your threshold. And then you hit the magic number three.

Human cognitive and social evolution has tuned us to conformwhen three peers show a behavior. This setting is a key aspect of human social behavior. You can imagine how it might vary across species: flocks of birds or schools of salmon might need only one or two adjacent nodes to trigger conformity; polar bears might need, say, five or seven.

The 1955 series of experiments by psychologist Solomon Asch demonstrated the almost embarrassing power that three peers have to influence our behavior. An unsuspecting research subject was embedded in a group of actors who were purposefully giving wrong answers to the simplest of visual tasks. The group was shown a vertical line segment and given a multiple-choice test asking which other line matched it in length (Figure 21-1a). Midway through the study, the actors began intentionally getting it wrong, and Asch measured how often the true subjects did too.

Figure 21-1. In the conformity study by Asch (1955), (a) the lines were shown above without their lengths, and participants were simply asked to match the Standard to the Comparison line. The results (b) showed the percent of participants who conformed by giving wrong answers on at least half of the trials. i

When no one was around screwing with our heads, we erred in only 1% of the trials; but when others erred, we did too, up to 35% of the time (Figure 21-1b). But here’s the interesting part. When only one other person in the room screwed up the test, we were not influenced, nor were we influenced very often when two others did. At three, we reached our threshold, and our conformityto others’ wrong answers hit its peak. But it was also an asymptote: when the number of idiots around us went up even further, to four or five or even 16, our rate of conformity rose no further than what it was with three peers.

Psychologist Harold Kelley explained what we were thinking in his 1973 theory of attribution, which examines the causes to which we attribute others’ social behavior, including odd behavior like in Asch’s study. ii When only one peer made a mistake on Asch’s line-length task, we attributed the error to his or her disposition, that is, something unique to the individual such as vision, intelligence, or deviance. In short, we decided their behavior was due to something in their internal world, not the external world, and thus, we were not in any way compelled to change ourselves. When two people erred, we began to think perhaps something in the external world was the cause of their behavior, but we had one more excuse left: we decided that their behavior was temporary, that is, caused by something momentary, unstable over time, a lapse of reason, or a slide in the projector that loaded wrong. So again, we didn’t think we had to conform. But when three people showed this unexpected behavior, and when they showed it repeatedly, we were forced to acknowledge that a real change in the free-standing world must be the cause, and it was time for us to follow suit.

In Ash’s experiment, the power of three was so consistent, it even went the other way. When we were given an ally in the room who agreed with our correct, if rebellious, answers (making two total rebels), rather than the wrong answers given by others, our rate of incorrect conformity dropped off significantly, but not completely (Figure 21-2). When we were given two other rebels (making three), we no longer made any mistakes at all.

Figure 21-2. In the conformity study by Asch (1955), three rebels (including the self) giving correct answers despite the majority were needed to produce the maximal non-conformity.

Just as three points define a plane in geometry, three peers reveal a socially-constructed truth in psychology. And right or wrong, we conform. This is why we need to see only three restaurant or business reviews on Yelp or Angie’s List (full-length reviews that is, not star ratings) to make up our minds. Lightspeed Research confirmed this in 2011 and Bright Local again in 2013, showing that reading three reviews was most common (Figure 21-3).

Figure 21-3. Adapted from separate studies by (a) Lightspeed Research (2011) and (b) BrightLocal (2013) showing that only about three reviews are needed to influence consumers. iii

When we see just one bad review, we might attribute that opinion to (for restaurants) the pickiness of the customer or (for apps) their ineptness with technology, that is, some internal factor specific to them. When we see two bad reviews, we might think it applies only to one bad day in the kitchen or an earlier version of the app, that is, something temporary. But when we see three bad reviews spread out over time, we begin to conclude the reviews are reflecting the external, stable reality of the restaurant or app that we too will experience if we also eat there or install it. Beyond the third review, however, we’re not likely to even read any more, and if we do, they will have a marginal impact on our receptivity.

Key Point

Conformity reaches an asymptote after three others influence us, so accordingly, few people read more than three online reviews.

Kelley’s attribution theory also helps us understand why we are less receptive to reviews from certain parties. When the recommender seems to have an incentive, other than the quality of the product itself, we engage in attributional discounting. This means we lose confidence in the quality of a meme when a positive recommendation for it appears to be caused by self-interest. Negative reviews can also be discounted, and our confidence in a meme increased, if you appear to be criticizing a meme that competes with your own.

This is why you, as the creator of your meme, are among the least influential or persuasive recommenders. We discount the strength of your site, app, or blog post as the impetus for your recommendation, since we assume you stand to gain attention or revenue for promoting it. Of course Tim Cook likes the Apple iWatch, we reason to ourselves, his stock holdings depend on it; so perhaps the iWatch is not as great as he says it is. This is an example of discounting.

As such, all things being equal, we should be more receptive to a retweet about your meme than to your original tweet about it. This is because we discount your original tweet of your own product, due to your self-interest in its success, whereas when someone else who has no financial stake in it retweets it, we attribute their actions to the product itself. A llrecipes.com, the world’s largest cooking site, verified this in a survey of 621 site visitors in 2011. iv We liked retweets more than original tweets, and we less often perceived them to be bald-faced advertisements (Figure 21-4). But most importantly, we were more willing to click the links in retweets than in original tweets. Because these links brought attention to Allrecipes or its partner advertisers, the difference in our receptivity directly impacted their revenues.

Figure 21-4. Attitudes toward tweets and retweets from Allrecipes.com . Average ratings (5-point scale).

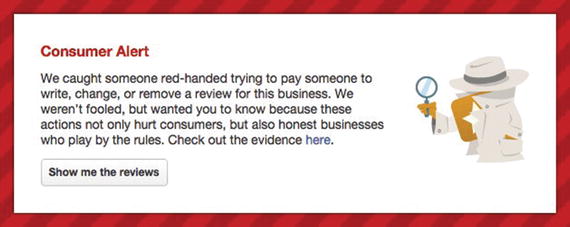

Discounting is also a big problem on Yelp and Amazon . Both sites have grappled with restaurant owners and authors who fraudulently pay people to promote some products and detract from others. After years of complaints, Yelp took to deleting suspicious posts, but this was not enough to quell the problem. So finally in 2015, Yelp began alerting us of fraudulent reviews and even showed us to the screenshot evidence (Figure 21-5). Yelp “wanted you to know because these actions not only hurt consumers, but also honest businesses who play by the rules.” What they also should have said was that our discounting of the reviews, the eroding of our confidence in them and in the restaurants and books they claimed to represent, was also bad for Yelp. Crowd-sourced reviews are among the most important content that such sites possess.

Figure 21-5. Yelp inserted warnings on business profiles that were caught paying for reviews circa 2016.

All told, discounting is a big reason that social media has turned out to be a poor place for direct-advertising and calls-to-action in which you ask us directly to view or buy things. Because they are presumed to be “social,” Twitter , Instagram, and Facebook give us the expectation that it is a place for organic conversation between real humans, which may occasionally reference brands or products. But almost every social-media marketing consultant advises that it is better to tweet truly informative content or customer-service messages than it is to promote offers. Nielsen confirmed this in a 2013 global survey, showing that while 84% of us trusted “recommendations from people I know,” and 68% of us trusted “consumer opinions posted online,” only 48% of us trusted “ads served on social networks”. v

Key Point

The appearance of self-interest leads us to discount recommendations. This is why we are more persuaded by retweets than by original tweets.

Not all recommendations influence our receptivity, nor do we give all recommenders equal weight. Social influence theory also holds that the strength of their relationship to us and their psychological immediacy(Chapter 18) also matters. Your spouse influences your receptivity more so than your friends, and he or she influences you more when standing in your bathroom than when sending a text.

Leveraging this, the cheeky 2010 Old Spice ad campaign featuring a ridiculously attractive male actor saying “I’m the man your man could smell like” had a subtle but powerful nuance: it encouraged spouses to recommend the product to their men. Spouses have as strong and immediate influence on our behavior as it gets. By the end of 2010, year-over-year sales of Old Spice body wash shot up 125%. vi

When a meme is recommended to one of us, there are three parties involved: myself, the recommender, and the meme being recommended. Way back in 1946, psychologist Fritz Heider vii examined these triadic relationships and concluded that only four patterns were in balance. Put in terms of memes, Heider’s balance theorywould hold that…

I like memes (+) promoted (+) by people I like (+).

I like memes (+) criticized (-) by people I dislike (-).

I dislike memes (-) promoted (+) by people I dislike (-).

I dislike memes (-) criticized (-) by people I like (+).

The signs represent the positive or negative sentiment between the people and objects. We know these patterns are in balance because, as Heider showed, when you multiply the three signs the product is positive. When this happens, the arrangement will say stable over time and not change. Taking an example from the 2016 U.S. presidential elections, we would be in balance if we liked (+) the idea of legalizing marijuana, promoted (+) by a candidate we liked (+) such as Bernie Sanders (Figure 21-6).

Figure 21-6. An example of Heider’s balance theory .

What happens if the product of the signs is negative and the triad is out of balance? What if all of a sudden, for example, Donald Trump whom we disliked (-) promotes (+) legalized marijuana (+), and the product of the valences is negative? Such a state of affairs is awkward and unsettling, that is, out of balance. So what would happen? Heider’s answer was simple: something tends to change. His key insight was that the most mutable part of these relationships was the first part of the sentences above: our attitude toward a meme. So in this example, we would most likely turn against legalized pot. We strive to keep our positive relationships friendly, and we change our negative relationships slowly if at all. And when someone promotes or criticizes someone or something publicly to others, it is hard to walk back. So the easiest thing to change is our own opinions, and this is what makes us receptive to influence. Put another way, we often come to like or dislike memes to signal our fondness for our friends and maintain harmony and loyalty.

Heider’s balance theoryalso applies to triadic relationships between people…

I like people (+) promoted (+) by people I like (+).

I like people (+) criticized (-) by people I dislike (-).

I dislike people (-) promoted (+) by people I dislike (-).

I dislike people (-) criticized (-) by people I like (+).

This echoes the ancient phrase dating back to the 4th century B.C. that “the friend of my friend is my friend, and the enemy of my enemy is also my friend.” But fast-forward to 2010, and Heider’s historic predictions were found to apply perfectly to the modern environment of a massive multiplayer online video game.

In the game Pardus, launched in 2004, players were enabled to “live in a virtual, futuristic universe in which they explore and where they interact with others in a multitude of ways to achieve their own goals” (Figure 21-7). The key to the study was the fact that we could declare whether other players were “friends” or “enemies.”

Figure 21-7. The massive multiplayer online browser game Pardus .

Key Point

Massive multiplayer games confirm half-century old predictions about triadic relationships.

A team of researchers led by Michael Szell noticed that this was the perfect environment to test Heider’s theory . viii Szell’s team analyzed the relationships and interactions of nearly all 300K Pardus players since the game was launched (Figure 21-8). They found that, as predicted, interactions between balanced—(+)(+)(+)=(+) and (+)(-)(-)=(+)—triads were common, whereas interactions between imbalanced—(+)(+)(-)=(-) and (-)(-)(-)=(-)—triads were rare. Digging deeper, they found that we didn’t often switch the valence of our relationships from positive to negative, which Heider argued was slower to change than our attitudes. Instead, we just avoided interactions with these unbalanced and unsettling threesomes.

Figure 21-8. The massive multiplayer online browser game Pardus . Adapted from Szell, Lambiotte, & Thurner (2010)

Heider’s theory also has another implication : balance can be achieved in threesomes, but it breaks down in foursomes. LinkedIn found this out when they tried to leverage an obvious usefulness of their network: asking someone to introduce you to another.

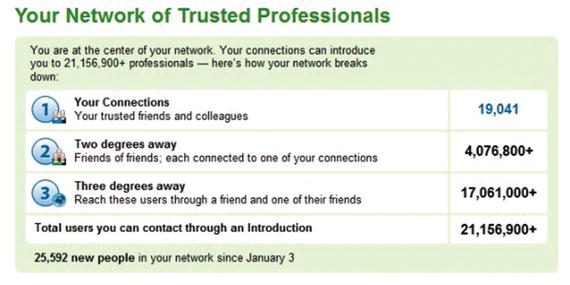

For years, a graphic on LinkedIn informed us that although we may be only connected to a few hundred people directly, we were connected to thousands of second-degree professionals and millions of third-degree professionals (Figure 21-9). Thus getting referred to scads of people who might hire us or bring business opportunities seemed to be something that was possible on LinkedIn’s network. For sure, getting introduced to our second-degree connections through a friend in common was indeed a valuable gift to the world. This was a straightforward application of Heider’s balance theory: I like people (+) referred (+) by people I like (+).

Figure 21-9. A discontinued promotional dialog box on LinkedIn . ix

But it only works for three total people, which means LinkedIn only helps us get introduced to second-degree friends but no one beyond that. In Heider’s terms, the people that I like (+) cannot refer someone they don’t know personally (?) even if that person likes someone (+) whom they like (+). Writing for Forbes, consultant Carol Ross wrote in 2013, “Bottom line: I don’t recommend requesting an introduction to someone who is a third-degree connection. Keep your requests to second-degree connections, where you and the person you’d like to be introduced to have someone in common.” x

By 2014, LinkedIn had acknowledged this bottleneck of social influence and shelved the feature. Their customer service reported, “We’ve recently made a change preventing requests to third+ degree connections, as it created a poor experience which relied on a chain of actions for multiple users in order for two members to be introduced. At this time, we recommend InMails be used to reach out to third-degree connections.” xi

Key Point

You can have someone refer you successfully to a third party on LinkedIn , but that third party won’t be able to refer you successfully to a fourth party without getting to know you first.

The lesson in this is that your startup will never be able to start a viral cascade with a “friends and family” launch through your followers on social media . Your friends do indeed like you (+) and therefore they will like your meme (+) and they will dutifully plug it for their friends (+). But past that, out into the next ring of connections, their friends will have no receptivity to your meme based on your reputation alone.

The only way for the cascade to continue is if someone else along the way stakes their own reputation on it. Don’t worry, it happens. If you are careful and sensitive and diligent and artistic and you make sure to align your ideas with our psychology and our life’s goals, we will gladly vouch for it. We don’t need to be paid to recommend ideas with excellent memetic fitness, and thus no one will discount our sincerity. Our friends (+) will like the memes (+) that we promote (+). And upon the third such recommendation, they will reach their receptivity thresholds too and start the process again.

Notes

Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological monographs: General and applied, 70(9), 1.

Kelley, H. H. (1973). The processes of causal attribution. American psychologist, 28(2), 107.

Lightspeed Research (2011, March). See also Charlton, G. (2011, April 12). How many bad reviews does it take to deter shoppers? Econsultancy. Retrieved from https://econsultancy.com/blog/7403-how-many-bad-reviews-does-it-take-to-deter-shoppers . BrightLocal. (2014). Local consumer review survey 2014. Retrieved from https://www.brightlocal.com/learn/local-consumer-review-survey-2014/#trust . See also https://www.brightlocal.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Local-Consumer-Review-Survey-20141.pdf .

Evans, D.C. & Epstein, E, B (2011). Can Twitter be used to advertise 3rd party products? Psychster Inc. Whitepaper in Collaboration with Allrecipes.com.

The Nielsen Company. (2013, September). Nielsen global survey of trust in advertising, Q3 2007 and Q1, 2013. Retrievedfrom http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2013/under-the-influence-consumer-trust-in-advertising.html .

D & AD. (2011). Case study: Old Spice response campaign. Retrieved from http://www.dandad.org/en/d-ad-old-spice-case-study-insights/ .

Heider, F. (1946). Attitudes and cognitive organization. Journal of Psychology 21 (2), 107–112.

Szell, M., Lambiotte, R., & Thurner, S. (2010). Multirelational organization of large-scale social networks in an online world. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(31), 13636-13641.

See also Cathey, G. (2013, April). How to find your LinkedIn network statistics. Boolean Black-Belt Sourcing & Recruiting. Retrieved from http://booleanblackbelt.com/2013/04/how-to-find-your-linkedin-network-statistics/ .

Ross, C. (2013, July 16). How to ask for a LinkedIn introduction—and get one. Forbes. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/nextavenue/2013/07/16/how-to-ask-for-a-linkedin-introduction-and-get-one/#377941c16f47 .

Serdula, D. (2014, September 22). LinkedIn removes introduction requests to 3rd degree connections. LinkedIn. Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/20140922160219-4270384-linkedin-removes-introduction-requests-to-3rd-degree-connections .