We aren’t simply passive observers when it comes to deciding which of your digital memes to remember for later and which to let slide from working memory. We can’t be. Just as it is with our choice of where we direct our gaze, we actively decide, based on our goals of the moment, whether each piece of incoming information is a meaningful “signal” to be attended to and encoded, or a “noisy” distraction to be ignored.

From 1985-1995, before the Internet went mainstream, psychologists and marketers estimated that we were already making this choice among 300 bona-fide advertisements that we encountered each day, i about 140 of which were TV advertisements . ii By 2014, this estimate had grown to 360, but other forms of media were adding to the total count. For example, by 2012 over 2.5 million “promoted posts” appeared in our Facebook newsfeeds from some 13 million local business pages (see Figure 8-1). iii

Figure 8-1. Deciding between wanted and unwanted messages is a cognitively effortful activity in which we actively engage.

But, nowhere were there more demands on our attention than in email . iv By 2015, people across the globe were getting 205 billion emails daily, (112 billion business emails and 93 billion personal emails). On the job alone, this meant we were reading 88 emails and sending 34 each day, taking up about a quarter of our time at work. But between 2009-2013, the average number of text messages we were receiving tripled from 50 to 150 per day. Fully 80% of all emails sent in 2013 were spam, the very definition of distracting memes, and although spam filters were constantly improving, 20% of the mail in our inboxes were still unsolicited. And those spam figures only counted the emails that an algorithm thought was a waste of time.

Of course, the surest way to shield our working memory was simply to ignore all digital media ; just turn away, turn off, and log out. We could abandon any effort to distinguish between good and bad memes and just decide they’re all bad. But the cost of doing this would have been missing out and failing to take advantage of the internet to achieve our goals. Some sort of balance was much more reasonable.

Psychologists David Green and John Swets understood the rules of this balancing act as early as 1966. v Their signal detection theorydescribes the trade-off that happens as we decide to attend to or ignore incoming information. What they called “signal” and “noise” we’ll call good and bad memes, but the point is the same: information is either useful and relevant to our goals of the moment or a distraction. Here are the basic principles of signal detection theory adapted to digital media:

We continually adjust our threshold to attend to information or ignore it, depending on whether we want to avoid missing good memes or shield ourselves from bad memes. But these adjustments always come with a cost.

To catch more good memes (hits or true positives), the cost is wasting our attentional capacity on more bad memes (false alarms or false positives).

To shield our attentional capacity from more bad memes (true negatives), the cost is missing more good memes (misses or false negatives).

Camouflage ups the costs: As good and bad memes become harder to distinguish, we make more errors.

Perfectionism is punished: To catch the last 5% of good memes, we need to waste our attention on a vast number of bad ones. To ignore the last 5% of bad memes, we will miss a similarly vast number of good ones.

Here are those same principles now applied to how we decide between relevant emails and spam:

We continually adjust our threshold for reading emails depending on whether we want to avoid missing relevant emails or shield ourselves from spam. For example, when we’re trying to concentrate on something else, we raise our threshold and only read the most important emails. But when we’re waiting for an important email to arrive, we lower our threshold and read everything.

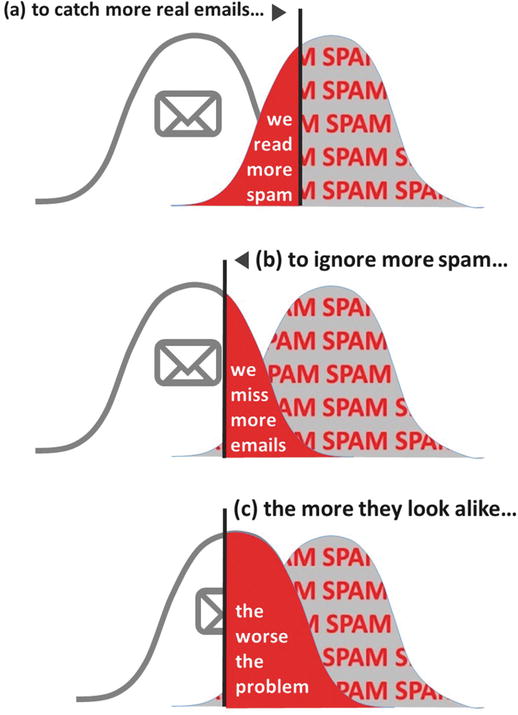

To catch more relevant emails we must waste our attentional capacity on reading more spam (Figure 8-2a).

Figure 8-2. When we shift our threshold to (a) catch more legitimate emails, the cost is to read more spam. When we shift to (b) ignore more spam, the cost is to miss more legitimate emails. The more legitimate emails and spam look alike (c) in their graphical treatment, the more errors we make.

To ignore more spam we must miss more relevant emails (Figure 8-2b).

The more similar relevant email looks to spam, the dearer the costs both ways and the harder it is to make the right choice (Figure 8-2c).

Ignoring the last 5% of spam requires that we miss many more relevant emails. Reading the last 5% of valid emails requires that we waste time reading much more spam.

Important note: In this discussion, we define relevant emails and spam selfishly, from our point of view as users. That means even an email from our family or our boss can be a spammy distraction. The engineers at Gmail focus on which emails should be delivered to a spam folder. So they call a legit email in the spam folder a false positive (falsely marked positive as spam), whereas for us a spam email we wasted our time reading is a false positive (falsely marked positive as something meaningful). Somebody should write Google and tell them to align their engineering terms better with the users’ point of view.

Key Point

We actively adjust our thresholds depending on whether we want to catch more signals or ignore more noise. But both adjustments have a cost. To catch more signals, we must attend to more noise. To ignore more noise, we will miss more signals.

But regardless, the cold logic of signal detection theory applies equally to Facebook posts, Twitter tweets, Pinterest pins, or even picking up the phone when it rings. One of the most tragically funny scenes from the TV series Arrested Development was when the phone rang next to the bed of the unemployed ex-psychologist Tobias Fünke, who had been recently pretending he was a comedian in the Blue Man Group . The call was from the actual Blue Man Group, asking him to audition. But Tobias was moping in bed with the covers pulled over his head. The narrator said, “The Blue Man Group finally calls Tobias with a life-changing opportunity. Unfortunately, he can’t hear it, so his life stays the same.”

What life-changing emails, tweets, posts, and pins are you ignoring right now?

Oh, that’s not fair. That’s exactly the kind of scare tactic that will trigger your “fear of missing out ” (a.k.a., FOMO) and make you lower your threshold looking for things you’ve missed, and therefore waste a few hours reading a bunch of junk. After that, you’ll realize we were just egging you on and you’ll raise your threshold again, now missing really cool stuff. Welcome to our world, the world of signal detection theory.

All kidding aside, this process is right at the heart of the memetic fitnessthat we talked about in the Prologue, the Dawkinsonian version of Darwinian sorting in which we, your users, are Mother Nature and our goals are the selection pressure that decides whether one meme is aligned with our needs and our nervous systems and worthy of encoding, and whether another meme is damned by a Gestalt violation, or a certain flatness, or a lack of realism, slating it for displacement before we waste more attentional resources on it than it deserves.

Signal detection theory was undoubtedly on the minds of Google engineers in 2013 as they tinkered with the Gmail web interface. Their business goal was to send us advertisements that looked a lot like emails. You can’t blame them—Gmail is free, so millions of us have it open all day at Google’s expense, and plenty of other companies were profiting from slipping in the occasional spam email. Google had been advertising above, below, to the side of, and all around our inboxes, not unlike the same practice in Microsoft’s Hotmail and Yahoo! Mail. But ads are always clicked more often if they are wedged right into the middle of the inbox, like spam. So how could Google get this performance on their own ads, without violating their informal mantra, “don’t be evil”?

The answer was a smart application of signal detection theory. They implemented a mix of elements that simultaneously camouflaged their ads among our emails , but also set the ads apart so no one could accuse them of spamming us.

First the camouflage : ads began appearing at the top of our inbox, looking for all the world like regular emails. They showed the sender’s name, a subject line, and the first part of the message. The boldfacing of the subject line was a nice touch: this led us to believe that it was an unread email that needed to be clicked on. All of this had the effect of elevating our rate of false positive mistakes, that is, perceiving an ad to be a real email and allocating attention to click on it and read it.

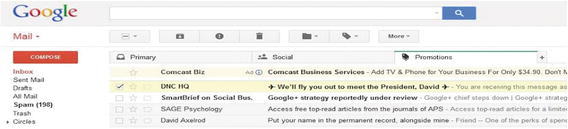

So at the same time, Gmail added a visual clue to set apart ads and emails: specifically, the tabs across the top that divided our inbox into “Primary,” “Social,” and “Promotions” emails. This was the opposite of camouflage; it helped us distinguish between corporate noise and organic email . And Google constrained itself to inserting its own ads only on the “Promotions” tab, mixing them in with the “buy this” mail we were getting anyway (Figure 8-3). Evil? Not evil? Most Gmail users voted with their clicks and kept on using it.

Figure 8-3. Ads appearing at the top of the Gmail inbox under the Promotions tab.

Gmail is not the only interface where we see designers like you doing what you can to distinguish good and bad memes for us. And if you don’t get around to doing it, we will. Users like us invented the Twitter hash tag precisely because it declared “this meme is good” when appended to a tweet. The whole reason that the hash # was added was also to distinguish signal from noise. Because we didn’t usually type this character in our normal conversations, including it in a search helped us look for tags rather than everyday words. As such, the results we got searching for #occupy were very different than when searching for occupy. The world was amazed at the cleverness of the crowd, but this was just a natural response to a signal-detection challenge.

Even with the best tagging, we can still be totally exhausted by discriminating between individual good and bad memes this way. The cognition of signal-detection and threshold-adjustment is very effortful. To be ensured that we only receive good signal, we are sometimes forced to take a step back and manage the entire channels by which we allow you to make demands on our attention. Rather than sort through the bytes, we need to scrutinize the whole cable. We apply the same signal-detection logic at the channel level that we did at the meme level. That is, we ask ourselves whether giving you the means to make demands on our attention is worth the returns. In this way, we become accountants in the attention economy.

Herbert Simon defined this term in 1971 saying “a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it.” vi Later in 2002, Davenport & Beck showed us that our attention has monetary worth and that it is not to be traded away freely. vii

Recognizing attention channelsis the first step to doing that, and the second step is assertively approving or rejecting the formation of channels in the first place. Each time we give our email address to a commercial entity like yours, each time we agree to friend, follow, subscribe, or join you, we establish a channel allowing you to make demands on our attention with more memes. The memes you showcase are always those that entertain, inform, or in some way provide value to us and move us toward our goals. But attached to them like remoras to a shark are the persuasive memes, those that are designed to influence our attitudes or behavior in a way that helps you attain your economic goals.

With each entreaty to open an attention channel with us, you declare in big bold letters that it’s “ free,” like the registration page on Facebook (Figure 8-4). We may not pay in cash, but we will pay in attention, which is just as scarce. The monetary value of attention channels is proven every time restaurants and retailers offer cash or discounts for an email address, increasingly under the premise that it’s an easy way to send us our receipt. Sorting through the ensuing memes is time-consuming and effortful, so yes, we had better get 10% off our hamburger for it. If nothing else, the best questions to ask any clerk who requests our email address are simply, “Why? What for?”

Figure 8-4. “Free ” services and monetary incentives given out for email addresses are evidence of their economic value to business.

This was the thrust of Davenport & Beck’s 2002 book. They recommended we oversee our attention like an accountant: we alone are in control of it, so we should track where it is spent and what we get for it. Attention is transferable, so we deserve transparency in how our attention is resold, like a mortgage security to an investment bank. And we may boycott abusive ventures by withholding our attention just as we withhold our cash.

Key Point

Businesses should analyze how much they are willing to pay to acquire more attention channels (e.g., email addresses) for marketing. Consumers should think about whether the financial rewards are worthwhile.

But at the core of it, the worth of an attention channel is determined by its ratio of signal to noise. The revolutions in mobile-, social-, and cloud-computing gave us an explosion of new attention channels to evaluate. For many of them, we were indeed getting useful memes that were meeting new needs fostered by computing on the go. Knowing great restaurants in our area was useful, reading reviews outside the front door was useful, and showing a clerk a coupon on our mobile devices as we checked out was useful. Therefore, the ads that we received through the same channels were largely worth it.

The terms of this attention-for-services trade-off are spelled out in the End User License Agreement that we click to accept every time we start using a new online service. But ironically, few of us read these EULAs because we screen them out with other distracting “false positive” memes. Yet there are provisions in EULAs that we may not want to miss. We make ourselves vulnerable to attentional demands precisely because we are trying to protect ourselves from them.

The new opportunity that more entrepreneurial meme-makers should explore is not adding to the attentional channels you have with us, nor pushing more memes through the ones you have. The opportunity awaiting innovation is to recognize what we said at the beginning of this chapter: we are not passive participants in signal detection, we are active. We do not want to receive spammy, poorly targeted, shotgun advertisements, nor incur the effort to sort through them, any more than you want to pay to send them, or to tell your advertisers just how bad the click-through rate is on them. Many companies like Google and Facebook are using algorithms to crawl our personal content to improve ad relevance, but this still positions us as passive eyeballs staring at a screen, a holdover from advertising’s origins in television.

You should instead actively involve us. Make us your partner. Ask us what we want to see ads for. Shopping is fun; we like it when we make it our task of the moment. Rather than hide your privacy settings where we can’t find them, make them a feature that gives us control and lets us express ourselves. “Here is what we sense you are interested in seeing ads for [exercise, travel, kayaking, dog sweaters]. Is that right? Feel free to uplevel or downlevel any, or shut any off.” As intelligent assistants become a real technology, we can have this conversation with them.

Google’s My Activity dashboard has taken the first step to reveal the attentional channels they use in a transparent way. It displays every voice-based search term, navigation route, online video, and web site visited, all of which they are using to target ads. But take a look at it and try to see how passive it still makes us feel. We have incredible brains to focus our attention and manage our identities—when will you include our input a high-value algorithmic parameter in your model? As long as you are showing us our “algorithmic selves,” why don’t you give us the means to manage it?

Perhaps best the way to get the most relevant ads, with the most signal and the least noise, and to get us to accept your algorithmic impression of us based on our activities in the online village square, is simply to involve us, give us more control, and to let us help you to see us as we see ourselves.

Notes

Rosselli, F., Skelly, J. J., & Mackie, D. M. (1995). Processing rational and emotional messages: The cognitive and affective mediation of persuasion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 31(2), 163–190.

Media Dynamics Inc. (2014). Adults Spend Almost 10 Hours Per Day With The Media, But Note Only 150 Ads. Retrieved from http://www.mediadynamicsinc.com/uploads/files/PR092214-Note-only-150-Ads-2mk.pdf .

Berger, A.A. (2004) Ads, Fads, and Consumer Culture: Advertising’s Impact on American Character and Society (2nd Ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Darwell, B. (2012). Facebook shares stats about businesses using pages and promoted posts. Adweek.com. Retrieved from http://www.adweek.com/socialtimes/facebook-shares-stats-about-businesses-using-pages-and-promoted-posts/287515 .

Radicati, S., Khmartseva, M. (2009). Email Statistics Report, 2009–2013. The Radicati Group, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.radicati.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2009/05/email-stats-report-exec-summary.pdf .

Radicati, S. (2015). Email Statistics Report, 2015–2019. The Radicati Group, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.radicati.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Email-Statistics-Report-2015-2019-Executive-Summary.pdf .

Green, D. M., & Swets, J. A. (1966). Signal Detection Theory and Psychophysics. New York, John Wiley & Sons.

Simon, H. A. (1971) “Designing Organizations for an Information-Rich World” in: M. Greenberger (Ed.), Computers, Communication, and the Public Interest. Baltimore MD: The Johns Hopkins Press, pp. 40–41.

Davenport, T. H., & Beck, J. C. (2002). The Attention Economy: Understanding the New Currency of Business. Harvard Business Press.