To place your meme precisely where we will be directing our fovea , and thus our attention, the first idea that likely occurs to you is to “learn our goals” and you would not be wrong. “Goals serve a directive function,” psychologists Locke and Latham wrote in 2002, summarizing 35 years of research on the topic. “[T]hey direct attention and effort toward goal-relevant activities and away from goal-irrelevant activities.” i But we want you to take a step back even from that. The first thing you must do is learn whether or not we even have a goal. If we do, then any meme that interrupts us will be ignored as a frustrating distraction. If we do not, we will be receptive to unsolicited and unexpected memes, although we will resist any effortful concentration required to engage with you.

Key Point

To meet our goals as users of your meme, the first thing you must do is learn whether or not we even have a goal.

In 1991, psychologists were given a research instrument as important to them as the telescope was to Galileo: functional magnetic resonance imagery . fMRI allowed them to see small changes in cerebral blood flow as we think or feel different things. For the first time, neuroscientists could examine the brain while we were awake and alive rather than anaesthetized or dead. So they began asking us to perform specific tasks to learn which areas of the brain were responsible for executing them.

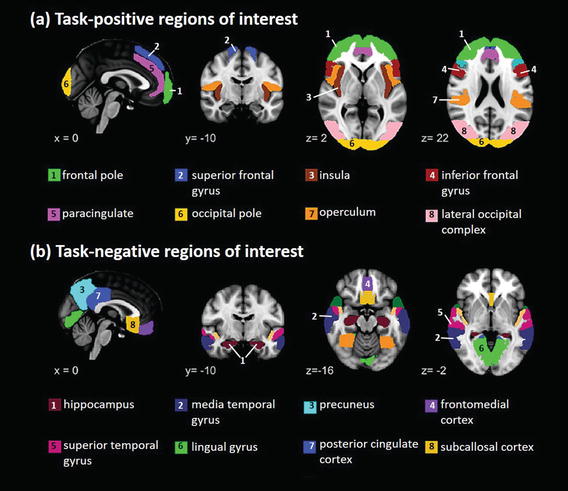

By 2014, Daniel Levitin, a neuroscientist on the front lines of the imaging revolution, summarized “one of the biggest neuroscientific discoveries of the last twenty years.” ii This was the existence of two fundamental patterns of activity in the cortex : the task-positive network and the task-negative network (Figure 2-1). According to Levitin…

thetask-positive networkis

“the state you’re in when you’re intensely focused on a task such as doing your taxes, writing a report, or navigating through an unfamiliar city. This stay-on-task mode is… [one] dominant mode of attention, and it is responsible for so many high-level things we do that researchers have named it ‘the central executive.’”

thetask-negative networkis

“the mind-wandering mode…a special brain network that supports a more fluid and nonlinear mode of thinking…[in which] thoughts seem to move seamlessly from one to another, there’s a merging of ideas, visual images, and sounds of past, present, and future.”

Figure 2-1. Brain regions in the (a) task-positive and (b) task-negative networks. iii

Essentially, fMRI studies showed first that no matter what problem they asked us to solve or task they asked us to perform, a similar network of pathways was activated. This was the task-positive network, including the pre-frontal, medial, and occipital lobes and other loci involved in processing language, symbols, and mental models.

The task-negative networkwas discovered more or less by accident, according to neuroscientist Matthew Lieberman. iv During most neuroimaging sessions, the researchers didn’t slide us in and out of the fMRI between tasks, but instead, they left us in there with the machine running. During the downtime, when we were listening to the hum of the electromagnets and solving no specific problem, the task-negative network appeared in our brains, and it too was remarkably consistent in its pattern. Our brains were defaulting to a state in which the medial areas deep in our cortex were at work as well as the hippocampus. When asked what we were thinking about, we typically replied we were daydreaming, remembering, and pondering over social situations.

Just like the functioning of our hearts and our kidneys, neuroscientists realized that there is no resting state for the brain. We are either solving an advanced symbolic problem like only our species can, or daydreaming to consolidate memories, see new connections, and try to understand the people around us.

As an inventor and promoter of digital media and experiences, your first objective is to understand whether we come to you in a task-positive or a task-negative mindset.

This is precisely what Allrecipes.com did, the largest community cooking web site in the world (Figure 2-2). They fielded a survey via a popup window with one question:

If you had to choose just one, which statement below best describes your visit today?

I had a specific goal. I knew what I was looking for or hoping to accomplish.

I did not have a specific goal. I was exploring and just looking for interesting information rather than something specific.

Figure 2-2. Task orientation in visits to Allrecipes.com .v

Allrecipes.com found that about 73% of us were task-positive and 27% were task-negative (Figure 2-2). As task-positive users , we were trying to make progress toward a known outcome, and so we wanted to be efficient and productive. We might be trying to figure out, for example, how to make a pomegranate reduction sauce for a lamb roast. As task-negative users , we were passing time, open to ideas, and just being a part of the community. We might be, say, getting new ideas in advance of a holiday, triggering memories of dishes we once loved but forgot, or looking to see what others were talking about.

But the more important lesson that Allrecipes learned was that task-positive and task-negative visitors used totally different navigation features of their site (Figure 2-3). Task-positive users among us tended to use a search field. This was attentionally the most economical way for us to get our reward. By contrast, task-negative users tended to browse the body of the site, clicking the pictures, links, and graphics in the hope that we would discover what we didn’t know enough to search for.

Figure 2-3. Navigational preferences for Allrecipes.comvisitors with a goal or no goal.

The realization that most of its users were task-positive helped Allrecipes.com make much smarter decisions about which features to invest in. They knew they had to have a very smart search algorithm and excellent search returns, since the majority of their users were task-positive. However, they could not ignore the minority who were task-negative and clicking links and going down rabbit holes, because these viewers were spending more time on the site and loading a lot more pages and hence more ads.

Allrecipes understood also that the mix of task-positive and task-negative users on their site was a function of their acquisition strategy. At the time this survey was conducted, Allrecipes engaged primarily in search marketing, and so the majority of us were coming in from Google. This predisposed us to being task-positive. We knew what we were looking for and we had begun looking for it well before arriving on Allrecipes’ domain. But later, Allrecipes put out a print magazine at the checkout aisle in grocery stores. This helped bring in more task-negative users who weren’t looking for anything in particular, but just wanted to browse cooking content. Balancing out the mix of task-orientation of their users with their acquisition marketing was an important way for Allrecipes to both meet our needs and overtake Foodnetwork.comas the largest global cooking community.

Key Point

When we are task-positive, we resist intrusions and find them distracting. When we are task-negative, will resist effortful tasks and welcome intrusions.

In essence, when we are in a task-positive mode, we point our fovea where we consciously choose to, in the service of trying to reach our goals, and we actively avoid everything else, which we treat as an unwanted distraction. If a majority of your users are oriented this way, as with many productivity platforms (Microsoft Office, Slack), you should avoid ad-support as a business model and instead steer toward a subscription model. If you display any ads at all, only do so in search results, because interstitial ads will perform poorly and be an annoyance. Your essential design strategy is to help us find what we’re looking for. Discard the thinking that, “if you build it, we will come” in favor of, “learn where we’re looking and be waiting.”

But the strategy reverses when we are in a task-negative mode. Now we welcome the attentional intrusions, including advertisements , and we resist expending the effort and concentration needed to solve things. If you’re building a mind-wandering app or web site like Flipboard, Reddit, Funnyordie, and most news aggregators, fill the real estate with thumbnails, headlines, and links, and load this content endlessly as we scroll down so there is effectively no end to the page. (This is the place for “if you build it, we will come” thinking.) Use machine learning to suggest content that is similar in category as what we’ve previously clicked (e.g., sports, election coverage). Adopt a social-marketing strategy where you post this same content elsewhere on the web. If you do use search marketing, optimize to search terms that are more general (e.g., “holiday recipes”) and less specific (e.g., “balsamic reduction sauce.”). In your own interface or on your own domain, do not in any way puzzle us with difficult navigation, advanced search forms, lengthy registrations, or anything that would require task-positive mental effort. On these sites you should follow the advice of usability guru Steve Krug and “don’t make us think.” vi

The neuroscientist Daniel Levitin writes of the task-positive and task-negative modes, “These two brain states form a kind of yin-yang: When one is active, the other is not.” Thus to survive this bottleneck , learn when and how often we are in each mode and adapt your design accordingly. vii

Notes

Locke, E. A. & Latham, G.P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717.

Levitin, D. J. (2014). The Organized Mind: Thinking Straight In The Age of Information Overload. New York: Plume. pp. 38–39.

Gordon, B. A., Tse, C.Y., Gratton, G. & Fabiani, M. (2014). Spread of activation and deactivation in the brain: Does age matter? Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 6, 288. Retrieved from http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnagi.2014.00288/ .

Lieberman, M. D. (2013). Social: Why our brains are wired to connect. Crown, New York.

Evans, D. C. (2009, August 3). Needs & navigation survey. Proprietary study commissioned by Allrecipes.com. Images and data used with permission.

Krug, S. (2006). Don’t Make Me Think! A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability 2nd Ed. New Riders.

Levitin, D. J. (2014). The Organized Mind: Thinking Straight In The Age of Information Overload. New York: Plume. pp. 38–39.