The last chapter introduced the idea of receptivity. This implied that we range from low to high in how receptive we are to adopting your digital innovation. Despite what our friends advise us about your meme, we don’t always “check it out.” We don’t always register. Or download. Or use it (or use it often). Or recommend it. Or pay for it. All of these are indicators as to whether we were receptive to your meme—or happy to have it blocked by our bottlenecks, like so much other noise on the network.

Key Point

The opposite of a meme being blocked by a psychological bottleneck is a meme that finds a receptive user.

The previous chapter showed that even with great memes, the social forces at play in who recommends it to us and how matter to our receptivity. We’re more receptive when three people recommend something than one, when it comes from someone with a strong, positive relationship with us, and when promoters are in our faces and immediate rather than recommending from a distance.

All of this frames receptivityat the individual level, focusing on the intra-psychological factors inside one brain. However, you must also think about how receptivity matters at the network level. Here, receptivity works in concert with other factors to determine the viral spread of your meme, things like the size of the network (the number of people), its architecture (is it a hierarchical corporation or a regular neighborhood), connectedness (whether everyone knows everyone or only a few others), and cliques (whether some folks in the network are cut off and know no one in other networks).

In this chapter, we take a look at emerging research that suggests that receptivity should be a key concern of yours in the successful launch of your digital venture. For decades, marketing consultants have advised you to launch to “influentials” who are connected to a great many others. But emerging studies suggest that the receptiveness of the many is more important than the connectedness of a few in triggering a viral spread.

Psychology, which has guided our advice to you so far, has over the course of its 150-year history focused mainly on individual organisms (and some small groups and families), but far less on the community or social networks . So while it has taught you a lot about how and if your meme enters one brain and gets passed to a second, all that drama involving perception, memory, and motivation now gets reduced to one node in the network as we zoom out to look at a whole species. And to be sure, a species is a different beast than the organisms of which it is comprised.

Any time a large number of nodes self-assemble into a network as complex as ours, new entities will emerge with properties that are entirely different than their constituent parts. A snowflake has properties entirely different than water molecules; a crocodile has properties entirely different than its eukaryotic cells. Just so, the shape and behavior of human networks may be entirely different than individual humans, requiring you to understand it as well.

How can you steer a company through the chaotic world of your customer network? Start by hiring some data scientists to plot your customers’ social graph. Simply visualizing your own network of users can be an extremely useful tool in understanding the challenges your meme faces at launch.

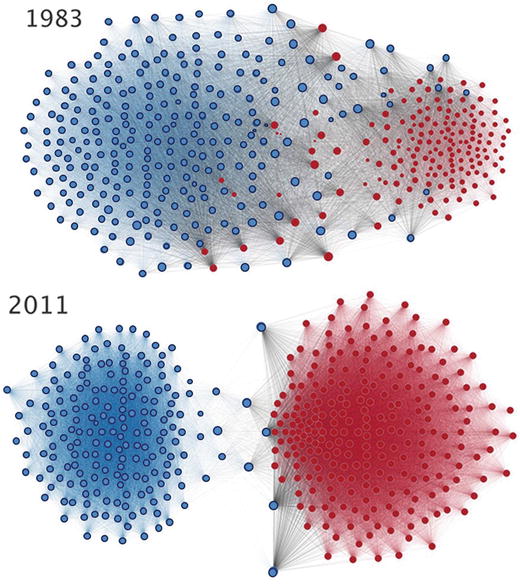

Illustrating that powerfully was the data visualization created in 2015 by a team of data scientists in Washington D.C. (Figure 22-1) i It takes only a glance to see how Republicans and Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives more often voted for each other’s bills in 1983 than they did in 2011. This is a classic example of a network clique where only a few mavens bridge otherwise disconnected networks. Before seeing this, you might think that the receptivity of one party to the memes of another was an individual-level problem; here, we realize it’s a network-level problem. It likely doesn’t arise from the individual values of lawmakers, but rather from systemic factors in the way their districts elect them. And it doesn’t result in just a dampening of bipartisan legislation; the networks are almost totally cut off from each other. From this view, you can count the number who actually “reach across the aisle.”

Figure 22-1. Voting patterns in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1983 and 2011. Blue/ringed dots are Democrats, and red/unringed dots are Republicans. Lines joining dots represent instances where they voted for the same bills. © 2015 Andris et al. Adapted and used with permission under Creative Commons (CC BY 4.0).

Key Point

Understanding the properties of the network in which you want your meme to spread is key. Receptivity should be a focus at the individual level and the network level.

Merely seeing your target network is a great first step to making more strategic decisions to help your meme spread through it. But there’s another more executive way to begin thinking productively about networks and start asking smarter questions to the data scientists that you hire. This is by leveraging a hypothesis-generating process called metapatterning.

Metapatterning is using a well-understood system as a metaphor to develop hypotheses about similar systems that are of interest to you. Charles Darwin used pigeon-breeding as a metaphor to articulate his theory of natural selection. Richard Dawkins used genes as a metaphor to describe the adaptive radiation of memes. Jeffrey Rayport is credited with first using the virus metaphor to refer to viral marketing strategies, although by that point it was already being used to explain computer malware. ii

Looking again at the graph in Figure 22-1 about the U.S. Congress, it could just as easily represent airline networks, the spread of Ebola, or neurons in our brain. Networks are found in living and non-living systems alike, and in this way, understanding any one system can help you understand the system that makes your company money. That’s metapatterning.

Kevin Kelly, the executive editor of Wired magazine , believes that metapatterning is essential to progress in technology:

“The more mechanical we make our fabricated environment, the more biological it will eventually have to be if it is to work at all. The world of our own making has become so complicated that we must turn to the world of the ’born’ to understand how to manage it. Ancient metaphors…of a machine as organism and an organism as machine are as old as the first machine itself. But now those enduring metaphors are no longer poetry. They are becoming real – profitably real.” iii

So, if you want to start providing immediate leadership about your user network, begin by likening other well-known networks to your own. Pick the one you know best or that interests you most and read up on it. It could be airlines, electrical grids, diseases, or our favorite, the nervous system. Then start asking your data scientists better questions with your metaphor in mind.

In every network there are…

Nodes, which are the entities connected (we think nodes is clearer than vertices, the plural of vertex, as they’re sometimes called)

Links, which are the connections (we like links better than edges when talking about people, but we also like channels)

Signals, that which spreads through the network (in your case, memes)

These vary from strong to weak:

Hub nodesare highly connected nodes with many links

Bridge (or maven) nodesconnect what would otherwise be isolated cliques

(Low) threshold nodesare those that readily forward memes on

Strong linksreadily reach the threshold of the next node

Strong signalsspread further and faster than weak signals

Can the list of network properties above and a little metapatterning help us understand the 2007 debate about influentialsthat classic marketing gurus Ed Keller and Jonathan Berry had with network scientists Duncan Watts and Peter Dodds?

Keller and Berry built an entire literature around the idea that if your meme is recommended by highly-connected influentials, it will have a much better chance of spreading. Targeting influentials can indeed be strategic because it gets the word out without spending the money to canvass everyone through direct-marketing. “If word of mouth is like a radio signal broadcast over the country, influentials are the strategically placed transmitters that amplify the signal, multiplying dramatically the number of people who hear it.” Keller and Berry wrote in 2003. iv By also defining influentials as thought leaders, well-read, cool, and/or political, Keller and Berry argued that others would be receptive to their recommendations.

Enough multinational companies like Nike have succeeded with the endorsements of élite athletes or celebrities that some part of the influentials hypothesis must be true. And as we saw in Chapter 18, attractive spokespeople are known to be effective peripheral routes to persuasion, especially when your value proposition is weak or lacks differentiators (like T-shirts and tennis shoes). All of the thought-leaders in this debate agree with the same 1955 two-step flow theory of marketing by Katz and Lazarsfeld, v which holds that the TV alone almost never drives sales directly; instead, commercials almost always drive a recommendation that gets someone to a checkout line.

But one thing influentials do not do any better than anyone else is help things go viral.

This blockbuster conclusion that Watts and Dodds arrived at in a 2007 modeling exercise vi was stunning, since the key feature of influentials is that they are connected to a much larger number of people than the rest of us. No one disputes this part. Most organic networks are what network scientists call scale-free, meaning the connectedness of nodes range from gigantic hubs with millions of connections (think Ashton Kutcher or Kim Kardashian) to sparsely connected satellites with few connections (your 81 year-old neighbor Marty who emails you using his iPad Mini). Thus, if influentials are hubs, then their recommendations can and do reach more first-degree relationships than others among us.

But if you follow the memes that influentials recommend out to the second- or third-degree, Watts and Dodds found that the typical viral cascade started by influentials does not have an appreciably greater reach than the cascades started by than anyone else. As Watts and Dodds put it, “Cascades do not succeed because of a few highly influential individuals influencing everyone else, but rather on account of a critical mass of easily influenced individuals influencing other easy-to-influence people.”

In network terms, this early finding (we look forward to more research) found that low-threshold nodes are a greater predictor of the reach of viral cascades than highly connected hubs. Receptivity is key. The subtitle of Keller and Berry’s book said One American in ten tellsthe other nine how to vote, where to eat, and what to buy. Watts and Dodds essentially found that, but what is important is that they do.

Key Point

Emerging studies suggest that the receptiveness of the many is more important than the connectedness of a few in triggering a viral spread.

What metaphor summarizes this? Let’s try airlines. Keller and Berry essentially argue to start your journey at big hubs like Heathrow or Atlanta. Watts and Dodds say it’s better to plan your trip through airports with the most on-time connections, like Salt Lake City or Ronald Reagan.

Makes great sense, but Watts and Dodds used metapatterning even more poetically:

“Although [our] claim may seem implausible in light of received wisdom, it has numerous analogues in natural systems. Some forest fires, for example, are many times larger than average; yet no one would claim that the size of a forest fire can be in any way attributed to the exceptional properties of the spark that ignited it or the size of the tree that was the first to burn. Major forest fires require a conspiracy of wind, temperature, low humidity, and combustible fuel that extends over large tracts of land. Just as for large cascades in social influence networks, when the right global combination of conditions exists, any spark will do; when it does not, none will suffice.”

Receptivity is just that: a conspiracy of attention, perception, memory, disposition, motivation, and social-influence. When the right combination of psychological conditions exists, any meme has a chance; when it does not, none will survive.

This closer look at whether influentials actually influence anyone prompted many web giants from Twitter to Klout to LinkedIn to improve their formulae for VIPs. They realized that you may tweet your idea to your many followers, but it is our mass willingness to retweet that makes your tweet go viral. The makers of the Klout score, a metric purporting to measure influence, had to stop simply measuring your number of connections, and make their score take into consideration whether any of your recipients passed it on. vii LinkedIn scrapped definitions of influentials based purely on connection-counts to instead hand-pick 500 influencers (including Richard Branson, Bill Gates, and Arianna Huffington) and work with them to publish long-form posts on their network.

This was an improvement. A promoter who recommends a meme to people who are not receptive is a spammer. A detractor who hates on a meme to deaf ears is a troll. Nobody wins and nobody loses if nobody’s listening. The meme that is recommended to a network of the unreceptive doesn’t spread.

Influentials are still important. The scope of Keller and Berry’s hypothesis was sharpened, not scrapped. Their formulation still applies well to hierarchical networks, like corporations or militaries, with a well-defined top-down chain of command. But the strength of the links between managers and reports is far more assured than in organic, scale-free networks, where some people influence us only weakly. Out here in the organic fabric of everyday networks, all of us have to choose how how to invest our attention into memes, and the only authorities are psychological and social. Out in the marketplace, we don’t reach our receptivity thresholds and allow memes to pass through our psychological bottlenecks because we’re told to. We only do it if we want to.

The notion that corporate networks are not consumer networks teaches an important lesson about metapatterning. Metaphors are only helpful if they are applicable. Network science is starting to show us how to measure and quantify the similarity between systems, starting with networks. When this matures, it will be a great help to leveraging our understanding from one domain into another. In the next chapter, we trace the origins of network science as we consider just how far your meme can spread if it gets it completely right.

Notes

Andris C., Lee D., Hamilton M.J., Martino M., Gunning C.E., Selden J.A. (2015). The rise of partisanship and super-cooperators in the U.S. House of Representatives. PLoS ONE 10(4): e0123507. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123507. Retrieved from http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0123507 . Image © 2015 Andris et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Rayport, J. (1996). The virus of marketing. Fast Company, 6(1996), 68.

Kelley, K. (1994). Out of Control. Reading, PA: Addison-Wesley.

Keller, E., & Berry, J. (2003). The influentials: One American in ten tells the other nine how to vote, where to eat, and what to buy. Simon and Schuster.

Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld, P.F. (1955). Personal Influence; the Part Played by People in the Flow of Mass Communications. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Watts, D. J., & Dodds, P. S. (2007). Influentials, networks, and public opinion formation. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(4), 441–458.

Klout. (2016). Retrieved from https://klout.com/corp/score . “It’s great to have lots of connections, but what really matters is how people engage with the content you create. We believe it’s better to have a small and engaged audience than a large network that doesn’t respond to your content…There will always be new social networks, new ways to engage with people, and more ways for us to measure real-world influence and expertise, and we will work to incorporate them all.”