Conversational knowledge sharing can (and will) only take place in a supportive social atmosphere. Such an ongoing environment is what we have come to call "culture." An organization's culture should be aligned with its values, mission, goals, and strategy, but the culture doesn't have to be defined by them. Different subcultures can exist in alignment with each other within one organization or even across different organizations.

The knowledge network exists first within the organization's greater culture. It may grow out of a more local subculture such as an area of expertise or a functional division within the organization. And it will probably develop its own unique subculture once it goes online. An online knowledge-sharing culture requires certain conditions and nutrients just as an orchid can grow only within certain ranges of temperature, humidity, and soil conditions. Yet unlike an orchid, an online knowledge network can adapt to changing conditions through its conversations and technology.

In this chapter, we describe these ideal cultural conditions. We discuss how how to create or migrate to them. We also elaborate on the nutrients that are necessary to start and grow a healthy knowledge-sharing culture within an organization: the analysis, the motivation, the leadership, and the trust. For most organizations, deliberate knowledge sharing is a new direction, and supporting it will entail some cultural change. So we also spend some pages on the change process and what it entails.

If a knowledge-sharing community is like an orchid, how do we create the right temperature, humidity, and soil conditions for its healthy growth and spectacular bloom? Some cultures might already offer the ideal conditions. Specifically, consulting firms—created for the express purpose of sharing internal knowledge, findings, and generating new knowledge, and packaging and selling that synthesized knowledge—are natural knowledge networks. Most organizations are not, though. This is especially true where individual specialization has always been rewarded and collaboration has not.

Taking the knowledge sharing online, which is the focus of this book, adds yet another cultural hurdle in the way of providing the best conditions for germination and growth. There is no prescription for an ideal culture that can fit all organizations, but there are certain values that must be honored in a culture if its members are going to feel free and motivated to share what they know and to collaborate around their shared knowledge.

Trust, as we've mentioned numerous times, is essential. If people think that, by telling others what they know, someone else will take credit for that knowledge or that an expressed opinion will somehow get them in trouble, they will not participate. Trust in an organization means that the stated rules and policies for using the network are clear and fair. It means that any incentives for contributing to the network provided by the organization will be real.

Tolerance is important as people begin to use new systems to take part in new formats of interaction. The online knowledge network is an arena where people bring their ideas, feedback, opinions, experiences, and questions. Its members must sometimes walk the fine line between being frank and being rude. In a virtual environment where facial expressions and tones of voice are lost, that line becomes even finer. The organization must be receptive to criticism and encouraging to truth. Knowledge does not always come neatly packaged, and in an active and open knowledge network, it may sometimes be presented in unsettling forms.

An assumption of mutual reward answers the key question, "What's in it for me?" Communities are places of exchange, where members expect to get things (not necessarily material things) of value from each other. They are not places of one-way contribution where members give to some greater entity in return for nothing. There must be satisfaction in participation, or people—even if they are being paid for it—will not contribute knowledge of value.

A characteristic of every enduring virtual community we've ever heard of has been a sense of place. It was vivid to us after our first months of participating in the Whole Earth 'Lectronic Link, better known as the WELL. Even though we were in the office or at home, sitting in front of our computer, we had a sense— as we read people's words and typed our responses to them—that we were actually somewhere else, where these other people were, in a space that was really nowhere specific. Our minds reacted as if we were "talking" to people in a room rather than typing in a "topic" in a "conference" on a "system."

In an ideal online knowledge-sharing culture, people will be able to find that sense of place. It is a product of trust and openness because the members of such a culture need to drop some of their defenses to participate at the level where they will tell each other the essence of what they know in a spirit of helpfulness and collaboration. A conversation requires that its participants return regularly to follow up. It requires engagement, which in turn requires a perspective of "going back to the place where conversation happens."

Informality is an important aspect, especially when moving social relationships online. The difference in format between face-to-face and virtual communication is enough of a challenge, but if interaction is kept rigid and businesslike without offering the opportunity to hang out and schmooze in the same environment, the trust, tolerance, and rewards will be hard to come by.

In his book The Great Good Place (Paragon House, 1989), Ray Oldenburg emphasized the importance of the third place, apart from home and work, where people feel free to socialize and relax outside their usual roles. Throughout human history, people have created such informal places to fill an important niche in their lives—the tavern, the town center, the bowling league, the church. The knowledge network is definitely part of the workplace, but within each organizational culture, there should be an opportunity to get to know one's co-workers and to interact in trust-building ways separate from the business process. Later in the chapter, we'll touch again on the subject of communities of practice and how they fit within the cultural framework of the organization.

The motivation to learn is the most powerful force driving participation in a knowledge network. Although all organizations have needs for knowledge and for the social networks that share, acquire, and generate it, few of them do a good job of recognizing and describing those needs in a motivational way. On the contrary, many organizations have cultures that inhibit knowledge sharing in one way or another.

Part of the motivation to learn must exist within the individual, and part must be motivated by the organization just as schools are meant to motivate their students. Schools motivate students for the good of the students, whereas organizations motivate employees for the good of the organization, but the cultural approach is similar; ultimately, the individual learner stands to benefit.

If the employees in an organization are looking to learn something important for the overall good of the organization, a knowledge-networking culture will serve them well. Their practical needs will help to build that culture. But the organization must take a role in supporting it, even where the employees are self-motivated. It must be okay for people to communicate and exchange what they know. The section on leadership later in this chapter will revisit this idea.

If one can "sense" a culture, how does one describe or evaluate it? How does an organization know what it's got, even when it thinks it has described its culture in a list of values or in a mission statement? An organization that aspires to have a knowledge-sharing culture might need to make some significant changes, or it may only need some minor adjusting. How does it know how far it needs to go to expect knowledge sharing to have an effect on the bottom line?

In their book, Built to Last,[60] James Collins and Jerry Porras examined 18 of what they called "visionary" companies to find out what made them successful and enduring. It turned out that exceptional leadership and business plans were not a common characteristic. Instead, they identified core values, clear purpose, and internal alignment as the elements that kept their exemplary companies steady as they adapted to a changing world.

"Those who built the visionary companies," they write in the introduction to their paperback edition, "wisely understood that it is better to know who you are than where you are going—for where you are going will almost certainly change." So an organization's understanding of its own core values and purpose is important in establishing a strong foundation from which the organization can move. If values, purpose, and internal alignment are unstable—changing with the winds of each new business trend that comes along—the organization's culture has little integrity.

Culture is a complex social characteristic of human groups. In addition to those values, purposes, and internal alignments, it includes structured relationships, language, etiquette, and history. Culture is built over time, through both deliberate and unconscious practices, and must be learned by newcomers to the organization if they are going to work effectively within it. Although culture is difficult to describe, its presence in an organization is undeniable and powerful, influencing—and in many cases, determining—behaviors and decisions as well as power structures and role definitions.

As we mentioned in Chapter 1, "Knowledge, History, and the Industrial Organization," Edgar Schein studied people and management in the workplace, observing that, since people are complex beings, no single management approach aimed at increasing productivity will succeed for all workers. Schein, as a social psychologist, also has done extensive study of organizational culture and cultural change. Two of his conclusions in this area are particularly relevant to us in this chapter:

Organizational culture exists on three levels

Within an organization, there are likely to be conflicting cultures

In Figure 5.1, the three levels of culture are represented. An organization's culture manifests on a visible, material level as artifacts. How it is taught to its employees represents a less visible level as espoused values. And it works to influence employees and their behaviors on an ingrained, unconscious level. These levels, though closely related, are not always consistent with each other. What you see on the visible layers of a culture may not reflect what's happening on the attitude and assumption layers.

Poor leadership and external forces can cause change and slippage in unconscious values even when the outward evidence of company culture remains constant and the values written into the company's charter go unedited. The Internet has imposed a challenge on all organizations based on rigid hierarchical management by exposing their employees and customers to the nonhierarchical natural communications flow of the Net. This exposure puts pressure on established chain-of-command cultures because people begin to use their electronic networks to communicate in ways that ignore the existence of the hierarchy. Underlying assumptions about "how things work" change before espoused values in the company can catch up.

As to conflicting cultures within the organization, the culture of a sales department, where commission-based incentives motivate internal competition, is going to be very different from the culture of an engineering department, where collaboration leads to higher productivity and better products. A sales culture may promise customers high levels of support that engineering can't afford to provide. A service culture that is open to conversing with customers may be at odds with a legal culture that fears company liability and the escape of proprietary information.

In some large organizations, entire departments compete with each other to serve the same customers, sometimes without even being aware of it. Cisco Systems sells its products through certified partners but also does direct sales to customers, often in direct competition with its partners. Sales and service teams have been known to stumble over each other in their attempts to communicate with customers. These situations indicate not only a lack of coordination but also the kind of misalignment in values that could be eliminated through more effective knowledge sharing.

When you work within a culture, much of it eventually becomes invisible to you, shoved into the area of unconscious assumption. An outsider often is more able to sense the deeper, unconscious aspects of an organization's culture than someone who has been immersed in it. A new employee may find the established ways of relating within the workplace to be wonderful, strange, or a baffling mixture of the two. Of course, certain of the espoused values will be made highly visible, or part of the company's mantra.

At Hewlett-Packard, the "HP Way" has been described and applied to employee behaviors since the early days when the founders still ran the company. Hewlett and Packard began a tradition they called "management by walking around" in which managers spend time having informal chats with employees in the workplace to get feedback and develop close ties. These are artifacts that help maintain the visibility of a culture—from managers walking around, to the company logo, to local jargon, to the décor of its offices, and to the dress codes that determine how people present themselves.

In the end, though, it's how the company—through its executive officers and managers—treats its workers and customers that is the most powerful manifestation of its culture. Practice, far more than ideals and values, slogans, and furnishings, describes the explicit culture of the organization. The criteria for hiring, compensating, and promoting people demonstrate the real-life priorities of ownership and executives.

So it's critical, when considering a change to (or an increased emphasis toward) a culture of knowledge sharing, that the changes go beyond the level of words and intentions. There must be real incentives and demonstrations of faith in the new cultural direction. The espoused core values must be made appropriate, and the culture must become aligned in the knowledge-sharing orientation across the entire organization.

To change an organization's culture so that it can, and will, effectively exchange knowledge as a regular part of its operations, the organization's leaders need to understand where its culture stands in the present. To reach that level of understanding, it should undertake two studies: a cultural assessment and a knowledge audit.

An organization should understand its current culture and the culture it aspires to before it begins the deliberate change process. A cultural assessment provides that understanding. This book doesn't pretend to be a definitive work on organizational culture, but we will cite here some widely recognized techniques used by specialists in the area of change management. Three popular and complementary approaches are gap analysis, goal alignment, and individual-organization fit.

Gap analysis is a term widely applied to environmental conservation. In that context, it identifies species that are not represented in current plans as "gaps" in conservation coverage. In the context of cultural assessment, gap analysis compares an organization's current cultural practices and assumptions with ideal practices in a desired culture, highlighting gaps between the two. The purpose of the analysis is to identify where the greatest gaps exist as well as where little or no gap exists. Thus, change efforts can be concentrated on where they are most needed, reducing the perceived task from one of total revolution to incremental or focused change. This saves cost and minimizes disruption within the organization.

Gaps can be measured along parameters associated with the three levels of organizational culture we discussed earlier in this chapter:

The visible evidence of the culture

The espoused values of the culture

The unconscious assumptions of the culture

Surveys administered to employees and analyzed according to their departments and positions can provide a good overview of what the people recognize as their culture or of their distinct microcultures. The ideal might describe the attitudes and assumptions that would be expected to exist in a knowledge-sharing version of the organization. It could be that the company already believes in open exchange of what people know but that it doesn't buy in to the value of taking its conversations online. Maybe its reliance on the decision making of a single leader or management team has made employees apathetic about collaborating to find new solutions. If the ideal is a culture that values open conversation, and analysis reveals a culture in which people feel intimidated when they speak openly about company issues, a critical gap has been identified.

Goal alignment addresses the problem of conflicting internal cultures. It first identifies different microcultures within the organization—whether they are defined by divisions, management levels, project-oriented teams, or geographically separate offices—and finds discrepancies in assumed goals between them. By understanding these different perspectives of the organization and its goals, efforts can be made to bring them closer together so that cross-company change can be smoother.

Goal alignment may not be as critical where the organization has chosen to lead its change efforts with a pilot subcommunity, beginning with the team or division that is most ready to adopt the new technologies and practices of knowledge exchange. In such cases, the vanguard group serves as the test case or as the cultural change role model for succeeding subcommunities, and the realignment happens incrementally as the new model proves its success. In any case, if the ultimate common goal is a knowledge-sharing organization, there will eventually be social pressure for distinct internal microcultures to come into goal alignment so that the knowledge exchange can take place not only within them but also among them.

Individual-organization fit looks primarily at placement and hiring practices and affirms that as the organization reorients itself toward its ideal culture, it is putting people in place who fit with its new direction rather than with its old one. In this way, new values can be imported to help push the transition from old, entrenched assumptions. For example, bringing in new people who are comfortable with using online media in group communications situations can break the ice in companies just beginning to move their interaction to the Net. In addition, recognizing where valuable individuals are being challenged in migrating their communications to message boards or email helps define the need for new training programs.

Objective cultural self-assessment is difficult for organizations because it exposes inbred subconscious attitudes and often unearths unpleasant formative histories. Some people, particularly in leadership positions, don't like to be reminded of failures and errors made in the past that remain embedded in current operations and culture. But if a company is to make itself amenable to change—as all companies should be in this fast-changing age—then it must begin by understanding what keeps it from changing. Bringing in a qualified organizational change consultant at this stage is a good idea.

Carl Frappaolo, executive vice president of the Delphi Group Inc. in Boston, says that for what he calls "knowledge harvesting" to be productive, there must be an environment where people are comfortable with sharing knowledge. To find out what defines such an environment for a given organization, a knowledge audit needs to be done. This, Frappaolo explains, is "a benchmark of where the organization is from a technical standpoint, a leadership standpoint, a work habits standpoint, a cultural standpoint, a communication pattern standpoint and a team structure standpoint." [italics ours] The results of the audit "will give insight as to whether the whole process of knowledge harvesting is going to be perceived as beneficial."[62] In other words, if people don't recognize any gains from knowledge exchange and harvesting in their jobs, they simply won't use the systems provided.

From a technical standpoint, the organization may not be providing the tools necessary to exchange knowledge effectively. As we emphasize throughout this book, the ability to converse and to share information through electronic networks broadens the possibilities for people who are not physically able to meet but who have access to the Net. The selection of online tools, as we'll describe in Chapter 7, "Choosing and Using Technology," also determines to a great degree the amount of knowledge exchange that can take place.

Company leadership (which we've covered before and will cover again later in this chapter) is another powerful determinant in the organization's willingness and motivation to adopt knowledge-sharing practices. Though many "bottom-up" initiatives instigate change, they require their own styles of local leadership— and ultimately, the support from the top—to be truly effective.

Work habits and communications patterns can be difficult to change. Where the mindset is such that an employee sees "knowledge" as only being of interest to the "intellectuals" in the organization, that employee is likely to resist working or communicating in ways that more openly share what he or she knows. This resistance may be rooted in a reluctance to expose one's intellectual property or from an inability to use the available means to describe one's knowledge eloquently. Either way, it's helpful for the organization to understand that these habits and patterns exist so that it can address them, on a case-by-case basis if necessary.

Because so much of an organization's culture, especially if it has a long history, is below the surface level and unconscious, assessment and auditing should be done with the aid of consultants who don't share that history. Fresh viewpoints—unsullied by skeletons in the closet and old axes to grind—are valuable here, as is an understanding of the special needs of knowledge-sharing cultures. Companies such as Denison Consulting (www.denisonculture.com) and the Hagberg Consulting Group (www.hcgnet.com) specialize in this field of assessment and evaluation.

Denison invented what it calls The Denison Organizational Culture Survey, which measures an organization's culture according to four traits: adaptability, mission, involvement, and consistency. Surveys administered to employees build scores on the evaluative tool that can be compared to benchmarks of other companies and correlated to other measures of company performance such as customer loyalty and sales. This is a kind of gap analysis. The tool also highlights conflicting tendencies within an organization, such as values for consistency of practice that may limit the organization's adaptability to changing circumstances.

An organization's overall culture influences the behaviors of all of its employees regardless of the microcultures in which they work, but most employees are more aware of their membership and allegiance to smaller communities within the larger one. Different motivations drive those smaller groups, and some—defined by their interests and practices—are much more likely to engage in conversation than others.

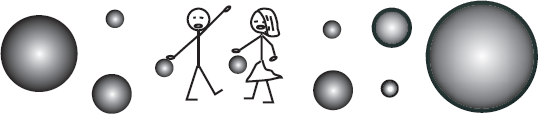

Online communities demonstrate these different tendencies very clearly. Communities come together around the common interests of their members, but the Web has provided a continuum of examples. At one end of that continuum, communities of people are comfortable convening around one-way content. They flock to the sites of celebrities or of products or news, and though they don't interact with each other, they direct their attention toward the same content. At the other end of the continuum, people are driven by a need to interact about their shared interests. People, and the varying degree of focus they bring to their communities, are represented in Figure 5.2. The degree of focus, represented by the variation from big ball to little ball, depends on the perceived importance and relevance to the group of its core interest.

For a project team, the focus will be large because the team members must devote their time and attention to achieving a common purpose within a given length of time. For a department in the organization, there may be many scattered foci, from attention to ongoing projects to the routines of departmental administration to the social planning for staff birthday celebrations. Because the attention of workers is split among them, none of these interests will be as important as the product is to an engineering design team or as raising customer satisfaction numbers are to the CRM team.

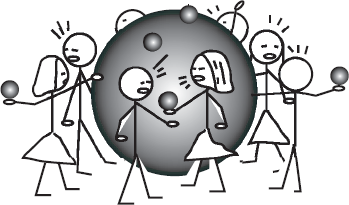

Many intranets serve communities of people who share interest in the information provided but feel little need to converse with each other about it. Instead, they may contribute to the content of the intranet by submitting ideas and suggestions to IT, the Webmaster, or to the intranet administrator. The communication flow is like a one-way broadcast with a contributing but silent audience. Figure 5.3 shows members of an organizational community all paying attention to the huge ball of relevant and essential content—company news, employee directories, policy statements, and HR forms—with some of them bringing their own offerings in the form of announcements and updates from the workplace. Conversation is not a priority when the content provides the sought-after knowledge.

Figure 5.3. A community focused on content of common interest such as a corporate intranet or Web site.

In an organizational culture, the content of the intranet is important as a shared database of information available to everyone. It is an important organ for imparting cultural values and communicating knowledge about the company itself. Separate areas of the intranet may serve the informational needs of the different divisions of the organization. Documentation of important cultural artifacts, such as the mission statement and company values can be referenced there along with profiles of fellow employees and their specialties.

On the opposite end of the continuum are communities with little in the way of shared interest but with a desire to socialize. Many of these formed spontaneously on the Web as chat rooms and message boards proliferated beginning in the mid-1990s. They are likely to form internally if the organization provides open, unrestricted opportunities for employees to communicate with each other through its intranet or if employees start their own internal email groups. Think of these as the third places in the knowledge network.

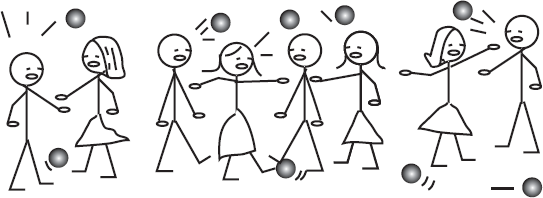

Conversations in such situations (see Figure 5.4) happen around topics, but the topics themselves are not as important to the participants as the contact and interaction itself. Though there is certainly some time-wasting potential in seizing these opportunities, they can effectively introduce people to the concept and practice of online conversation and allow people to get comfortable with new interfaces without the additional stress of forcing their conversations to be goal-oriented. However, even in a goal-oriented online community, it's important to provide some "free space" where informal conversation can take place.

Figure 5.4. The social interaction itself, rather than the knowledge gained from the conversation, may be the prime focus.

Most online conversations that take place within organizations happen in the context of some shared interest or purpose, with relevant content being at the center of discussion, as in Figure 5.5. This is the realm of project teams and communities of practice, which we discuss in more depth later in the chapter. Communities that form around shared interest in a subject—and have the means to interact—can reenergize their central focus with new collaborative ideas.

People in these arrangements discuss what is important to them in the workplace: their shared goals and the work that is at hand. The balance between interaction and content creates a kind of equilibrium, and both of our previous examples—where content was everything and where conversation was every-thing—will tend to gravitate toward this more balanced dynamic. Where people point their common attention toward content, they will want to discuss it more, and where people simply talk, they will tend to form communities of shared interests—requiring supportive content—as they discover commonalities.

Along the continuum from content-focused communities to interaction-focused communities, the middle ground, where content and interaction feed each other, is the most stable and rewarding, especially given the flexible toolset of the Web. Cultural migration can be leveraged by developing the organization's intranet to move employee participation from wherever it is along the continuum to this more balanced state of involvement, communication, and focus.

As we've pointed out, understanding its current culture can be an imposing task for an organization, but our main concern in this book is in describing the destination cultures that will value (and participate in) online knowledge sharing. From wherever a company is, it needs to arrive at a culture that encourages the smooth flow of knowledge and experience from where it exists to where it is needed. And as always, the most fluid, current, relevant, and usable knowledge resides in the minds of people both within and outside the company.

To get that mind flow going, some companies are proactive in developing practices and compatible technical systems that attract and support participation. Others are more reactive, following the spontaneous leadership examples of entrepreneurial employees who make use of whatever technologies are available to exchange knowledge and make their jobs more productive. The two sidebars describe these very different approaches.

Tacit knowledge is held in the mind of every employee. But not every employee is able to put that knowledge into words. As they address their workplace responsibilities, they develop skills and expertise that, through repetition, become almost instinctive. They become more productive but may not be able to describe the subconscious elements of their skills.

The company relies on tapping into this deep experience to more quickly bring other workers up to the same level of productivity. Often, the only method for doing so is visible demonstration, which can be a time-consuming approach. Yet, through the give-and-take of conversation—online or face-to-face—such ingrained techniques can usually be explained, coached, and transferred to others.

The key to unlocking such tacit knowledge is in motivating employees to participate in transferring their experiential knowledge to others. A companywide value in openness and sharing is more likely to motivate an individual than a culture that rewards workers for hoarding their experience to enhance their individual prospects. If workers are rewarded for revealing the secrets of their productivity rather than keeping those secrets, the benefits can accrue to the company's bottom line as well as to the individual's.

If a practice of knowledge harvesting is put in place, then everyone within the organization must be open to having his or her individual knowledge sources tapped. Everyone must be able to benefit in some way from the sharing, and everyone should have access to the resulting bounty of explicit knowledge or conversation. These and more concrete incentives are important because when the most generous are rewarded, the least generous will eventually get the point and follow.

Often, leadership from the top levels of the organization is hesitant to upset the delicate balance of the status quo by initiating new cultural practices or marshaling change within the organization. In such cases, individuals who understand their own needs and the capabilities of the technology available to them are likely to take some leadership into their own hands and tap into the minds of colleagues who can serve as their personal knowledge resources. This was the original "hackers' model" of innovation, dating from the early days of computer networking. We see more and more evidence of cultural change being initiated in this manner, where grass-roots models are built and executed before top-down cultural initiatives are able to get off the ground. But top-down leadership and example are crucial if core values are to change across the breadth of the organization.

For emphasis, we repeat: Unless the top tiers of the leadership hierarchy recognize the importance of knowledge exchange in the culture, there is little hope that grass-roots efforts will transform the entire organization. Some individuals in the company may pursue learning from each other, but knowledge as a driver of success and change throughout the organization will not be significant.

The CEO, of all people, should understand and represent the purpose and goals of the organization and how its culture relates to achieving them. This is more than a managerial relationship; it is a social leadership role that directly transfers to the behaviors and communications that happen all across the company. If the success of the company relies as much on generating and exchanging knowledge as it does on product development, production, marketing, and sales, then it is essential that the CEO make sure that its culture, at all levels, remains aligned with knowledge sharing, even if it has to change to do so.

Buckman Labs, a medium-sized chemical business in Memphis, is recognized as one of the leading examples of the knowledge-sharing organization. Its vice president of knowledge transfer, Victor Baillargeon, emphasizes the necessity of having buy-in by the "top brass." As he stated in an interview, "It takes clear leadership to set the culture and change it, and the leadership must remain involved. It's an ongoing battle. The challenge is to make it so that there is value in participating."[65]

We use the word knowledge endlessly in this book, but in the real world of the workplace, knowledge is less used and widely misinterpreted. Few people consciously seek knowledge in their daily jobs. Instead, they seek answers; they try to learn from each others' experiences; they look for records and histories that tell them what has been tried and what has succeeded. They attempt to contact people who understand the goals they are pursuing and the difficulties they are encountering. They hunt for experts and advisors. Rarely do they think in terms of knowledge gathering per se.

We use the term to represent all of the foregoing, but within the organization's culture, there may be other terms that are more appropriate and better understood. Cisco, which has for years deliberately shared know-how through its Web site, intranet, and extranet, rarely uses the word knowledge on any of these sites. Instead, you see many references to solutions, training, e-learning, and guidance.

The CEO may also think in general terms of improving knowledge management throughout the company or in specific business units, but his or her directives must describe the actual needs that must be fulfilled, whether they are to increase the speed of innovation or to generate more new ideas. It is up to the CEO to understand the organization well enough to know whether or not a senior manager needs to be assigned or hired to oversee the development of knowledge-sharing resources and practices and whether that person should bear a title such as chief knowledge officer (CKO) or, as we just described, VP of knowledge transfer.

Some cultures may need that titled person to oversee the cultural transformation, leading the organization from the assessment stage to the software design stage, through the implementation of new knowledge-sharing practices, and into the production phase where operations are monitored for success. Other cultures may find it more appropriate (and the change smoother) to allow workers to develop their own systems for sharing knowledge and, as Dave Weinberger suggests, to have the VPs and senior managers get out of the way. "It's not your job to create conversations, to create voices," he says to those titled leaders. "It's your job to listen to the conversations and voices already there."[66]

In leading transformation to a knowledge-sharing culture, it's unwise to expect change to happen overnight or even over the span of a year. For many people accustomed to other ways of doing things in the workplace, it may require several business cycles to recognize the improvement and get used to the new tools and techniques. That sense of place and culture may not arrive until some time has been logged actually exchanging knowledge.

As Victor Baillargeon described his experience leading change at Buckman Labs, "The first year they think you're crazy. By the second year, they begin to think it can work, and in the third year, they buy in."[67] You can get more buy-in by demonstrating incremental success, even if it's only in one small sector of the organization, than by promising that success will come for everyone at the same pace. The cultural assessment and knowledge audit should have identified the divisions or teams within the company with the most promise of improving through use of knowledge exchange. It is through watching the development of those high-leverage seed communities that new cultural values will gain a credible foothold within the organization.

The danger, as we've seen over the years in our own initiation of online communities, is that the CEO and board of directors will demand to see direct improvement on the bottom line in the short term rather than allowing the new practice to mature and catch hold. Social practices, especially those taking place virtually, rarely work that quickly. They must be permitted to find their way through some trial and error before they "click" and build a critical mass of participation and exchange. But leadership can and should define goals toward which teams can strive as motivators for advancing the use of their knowledge-sharing systems.

The building of a knowledge network begins with a perceived need to know more and to know it sooner. That need not only justifies the expense of reorganization, technology, and new leadership positions, but it drives the buy-in by employees who must participate in the network to make it a success.

A study by the consulting group McKinsey and Company[68] identified performance as a prime motivating factor in knowledge cultures. By setting goals and mileposts to measure improved performance in teams and business units, the need for attaining and circulating new information—for learning—becomes more valuable and urgent. Workers see the importance of extracting from each other all relevant knowledge and experience and of seeking the same from other people within the organization and outside the organization. Thus motivated, they innovate new practices using the communications tools available to them and look for ways to improve those tools to better fit their needs. Motivation and purpose, stimulated and set by senior management, spur innovation and collaboration. Where a relationship with IT has been established, that innovation moves smoothly into the area of creative interface configuration to shorten the time between stating the purpose and achieving it. Members of the motivated working group become conscious of any inefficiencies in their process and seek whatever means are available to streamline their activities, thus learning and implementing as one fluid and collaborative activity.

Organizations that define themselves as performance-oriented cultures push the development of the networking tools that enhance that performance. The role of knowledge network leaders (including the CKO and senior managers who may be closer to the specific projects or lines of business) is to provide the perspective and overview that spots inefficiencies and facilitates connections between people and the resources they need to eliminate those inefficiencies. This focused leadership serves as the liaison with IT and with the CEO whose purview must remain broad and long range.

Some leaders emphasize that workers should be careful with what they say and to whom. Thus, fear dominates the message that they send into the workplace. The result is an underground communications culture that protects itself and its conversations from the prying eyes and ears of management. If management gives the impression that it would rather not hear what workers have to say, even in the form of constructive criticism, then the idea of a knowledge-sharing culture has little hope of reaching fruition.

Former Intel CEO Andy Grove wrote a book titled Only the Paranoid Survive.[69] As the leader of one of the world's largest and most successful companies, he was not meaning to write a prescription for survival in the workplace but was describing his perspective from a key position in a company that was subject to the crises and sudden changes that occur in the modern world and, subsequently, in the marketplace. The aftereffects of 9/11 are only our latest example, but Grove's book was written 5 years before that event and puts paranoia to work recognizing the subtle evidence of approaching change that allows good leaders to avoid the industry-shattering changes that may follow.

Grove is considered by many to have been a great business leader. He writes of how leadership must relieve workers of the fear of change by recognizing the need for change far in advance, before it reaches the crisis stage. He describes the dangerously narcotic effect of the "inertia of success" and welcomes "Cas-sandras" who announce rumors of potential cataclysms. He also praises "free flowing discussion" and "constructive confrontation" as important to keeping management appraised of employee attitudes and concerns. Though his paranoid mindset is rumored to have trickled down into the engineering layers of Intel, he does at least talk a good game and describe what would be a good role model for a knowledge-focused leader.

Such a leader is a good listener, both inside and outside the organization. By doing that knowledge-gathering task on behalf of the workers, an attentive leader can steer the company along a successful path, motivating workers to contribute what they know and think by demonstrating to them that their knowledge and opinions are being put to use for their benefit.

The ideal results of good leadership and effective motivation are what Jun-narkar at Monsanto describes as "an ongoing upward spiral" of converting information into insight and formalizing new roles for people who make sense of information. And as we described in earlier chapters, the people active in the knowledge network will continue to refine its tools and techniques to make the exchange process all the more natural and productive for them.

Another key motivator for circulating knowledge among employees is intellectual stimulation. By engaging in conversation with people who have experience and information about topics of shared interest, one is exposed to new ideas, different perspectives, and the personal enhancements that people give to the things they know. When an organization gives its blessing to—and provides opportunities for—such interaction, people are likely to participate with enthusiasm. Where the topics of their conversations have some relationship to business goals, these communities of practice (CoPs) can actually help advance one's career.

As Etienne Wenger[70] describes them, CoPs are conversational communities convened around passionate interests. Participation in them is voluntary, driven by personal motivations, and they are completely self-organizing, requiring nothing from the organization except the access to online meeting tools or F2F meeting places. CoPs don't exist without motivation, for motivation is what creates them in the first place.

Organizations are just beginning to understand that by sponsoring and supporting CoPs in the workplace, they get to harness the most creative energies of groups of workers without having to devote management resources to organize and oversee them. When the focus of the CoP is related to that of the business, the business stands to benefit in ways that are unpredictable but potentially profitable.

An article about CoPs on the Intelligent KM site[71] suggests examples of these extracurricular but relevant communities, such as "multimedia application development at a software company, herbal remedies found in the Amazon rain forest at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), or aerodynamic automobile design at a car manufacturer." In all of these cases, hobbyists would come together to share resources and attempt to answer each other's questions while advancing collective knowledge. Often, a CoP coalesces around an acknowledged leader in the field: an expert or master who helps train eager apprentices. Members of the community bring new knowledge to it and, through cultural osmosis, into the sponsoring organization.

Because CoPs are more concerned with learning and innovation than execution and productivity, they may seem to run counter to the priorities of the businesses that sanction them. Yet they can add value to those businesses by serving social and research functions that the business may not feel at liberty to perform. And being relatively cheap to administer—requiring only the use of email, message boards, or simple group communication tools—they aren't a liability to management.

Members of CoPs must be aware that their time spent in the community is not company time or, if it is, that the community must give back to the company in some form. The most successful CoPs seem to be those that exist specifically outside the work environment, where their members are free to explore and experiment without concerns about the value or cost of their explorations to the company. Only under those conditions can their passions truly run free.

The most important side benefit of CoPs is that they allow employees to experience the potential of open collaboration and innovation. Having gotten a taste of that kind of interaction, many will be motivated to bring the same kind of energy, relationship, and collaboration into the organizational culture. And by being allowed to participate in CoPs under the company's approval, they may be less likely to leave (with their knowledge) for greener pastures.

A more centralized approach to motivating innovation in knowledge exchange has been practiced by the aforementioned Buckman Labs. By fostering communication and collaboration among people across the entire company, the scientists and technicians at Buckman are able to realize serendipitous benefits. They describe an example where scientists in their microbiological control division were stumped in trying to control the growth of an organism and were given the solution by an employee in another division who had learned to control the growth of a similar organism while practicing his hobby of brewing beer.

Self-organizing conversational communities are not inherently about control; in fact, most managers would find them frustrating to oversee. But as Dave Weinberger says, "You have to learn to love messiness—although messiness has been the sworn enemy of information management professionals." He gives the example of the employee database that tells all of the essential facts about the person but leaves out personal observations such as "that Sally is wickedly funny, that Fred is really creative but many of his ideas are bad, that Carlos is a great initiator but is weak on follow-through, and that Wanda is a great person to travel with."[72]

At the WELL, we learned through trial and error. The role of host was created at first to provide a level of autonomy to the WELL's members, allowing them to apply their interest and expertise to managing a diverse selection of conversation topics. Over time, though, certain individuals added other qualities to the host's definition. They not only brought some subject matter expertise to their conferences, but they also began practicing facilitation and social counseling, keeping conversations on-topic and resolving arguments and disputes among participants. Some provided information resources and organized "field trips" for members of their interest groups into the physical world. The best hosts attracted loyal communities who showed up daily almost as if they were voluntarily instructing classes at school.

In a conversational knowledge network, there are similar roles that need to be filled. And just as hosts became an essential part of WELL culture, these knowledge facilitation roles will become identified with the knowledge culture in an organization. At Monsanto, Bipin Junnarkar emphasizes the importance that roles play in the successful conversion of information into insight in self-directed teams. Because these teams work within the context of an organization, their level of performance is more important than in the less formal interaction of the WELL. Thus, the team leader must keep an overview of how the team is achieving the goals of knowledge creation and exchange. The leader must keep track of what lessons have been learned and feed those lessons back to the team.

It's not an easy role to fill, as Junnarkar admits. "It is a very new concept for the entire organization. We look at creating value at the level of the individual, to improve the capability of each person. And we're attempting to change organizational culture by sharing and learning from each other so that the core values of individuals and organizations overlap, which represents a change from the classical way of interacting."[73]

Another self-organizing subculture is that of the customer. Increasingly with the availability of the Internet, the public is able to get a more detailed impression of corporate culture. Web sites, more than most advertising, provide insight into the values and purpose of organizations. Customer service and support—all of the elements of customer relationship management—are now being provided through the Web. Hence, whatever the company's internal culture, it must take into account the public's exposure to it.

Customers now "talk" to one another online about the companies they buy from—what some have called "word of mouse." They want to connect with people inside of the companies they buy from, too. As Dave Weinberger says, "Customers want to talk with the crazy woman in your back room who actually comes up with all the good ideas as well as tons of bad ideas. They want to talk with the designers of the interface or of the controls. They want to talk with everybody who's involved with the product."[74] Those customers share a passion for the product with the company's employees, especially with the product's designers.

The knowledge community should extend beyond the firewall to the customers who care enough to provide feedback and try to connect with the company. This inevitably requires some cultural adjustment because the assumption in most companies for decades has been that there would be minimal interaction between the workplace and the customer. Today, through sophisticated customer relationship management (CRM) interfaces and innovative customer contact practices, the boundary between company and customer is becoming more and more transparent. But if the company wants to do a good job of conversing with its customers, it had better learn to converse internally first.

For many organizations, the change to a knowledge-sharing culture will be slow and at times difficult. It will cause disorientation and disruption because people are used to working in a certain way, within a certain organization, using certain tools. New skills will need to be developed and, as we've pointed out, different skills will be valued. Good writers and explainers will gain prominence; fluent users of technical interfaces will excel. Those accustomed to developing their specialized skills and to being treated as high-prestige local gurus will find themselves being asked to share their expertise openly with many others. People who have the social skills to entice others to reveal their knowledge through artful conversation will be recognized in new roles in the company.

The organization as a whole will need to emphasize values that may long have taken a back seat to profit and market share. As Victor Baillargeon said of Buckman Laboratories, "We have a code of ethics that is the firm's cornerstone and that contributes to building a climate of trust and respect." Shareholders may have to understand that to build for profits over the long haul, the organization has to adapt to the realities of the knowledge economy of the future where profit may only come to companies that understand the importance of trust and respect.

Buckman Labs' status as a leader in companywide knowledge sharing was not gained easily or quickly even though it concentrated on deliberate cultural transformation. It took 3 years for its employees to "buy in," Baillargeon admits. "I advise companies contemplating it to take a bite and get started. As you prove it works, you can grow it and migrate it into other parts of the company. You need a unifying technology that will be a good tool for your people."[75] And with that admonition, we move on to discuss some of those good tools in the context of the cultures that may be using them.

An organization that wants to share, exchange, and generate knowledge must have a culture that is aligned with the values that make such open transfer possible. Building or migrating to such a culture requires deliberate analysis of the starting point and the desired end point of the culture-changing process.

Different parts of the organization may have different cultures and ingrained habits that make them easier or harder to move toward the ideal knowledge-sharing culture. The company's leadership must clearly describe that ideal and make the call as to which of its diverse subcultures will lead the way in moving toward that ideal. This change can be accomplished by planned companywide reorganization and technical revolution or by allowing small, self-motivated, self-organizing communities of practice to serve as role models for the more formal divisions of the company.

A company's culture is increasingly transparent to customers, so it's even more important today that the company align its culture with the needs and expectations of those customers. The knowledge sharing can extend through the corporate firewall into the Internet where mutual learning can take place. The intersection of interests between the company and its customers is in the shared passion for products and in the use of common communications technologies.