People and their cultures are adaptive; that has been the story of the human race, and we constantly see evidence of it all around us. The personal computer, the Internet, and the Web have made us invent new ways of seeing and interacting with the physical world through our new virtual world.

We humans have proven over time that we can adapt to almost any condition or situation, and we use technology to make our adaptation easier. We've developed clothing to keep us comfortable in hostile environments. Our cars have eight-way adjustable seats and smart climate controls. We devise ways of interacting with technical gizmos as if they were human. Now we can design online environments that allow groups to communicate in Cyberspace in ways similar to those they use in the physical office space.

Our first five chapters were mostly about people, organizations, and culture because they are in fact the most important factors in the success of a knowledge network. This chapter introduces the relationship between those human entities and the interfaces that allow them to practice knowledge sharing in Cyberspace. We follow this chapter with one focused on the technology tools that work best as components in a knowledge exchange interface. The technical choices and design are important to the flow of information between people. They can block or inhibit that flow just as easily as they can make it possible or even improve it. But we begin by emphasizing a point we've hinted at in previous chapters: Keep the interface as simple as possible.

Unnecessary complexity should always be avoided. Change for the sake of change is often counterproductive. Interfaces with which a culture is already comfortable should be leveraged. This chapter is full of cautions and descriptions of pitfalls. There are many choices for online conversation tools available, and software producers are constantly hawking new "knowledge management solutions." If we have anything to recommend beyond keeping it simple, it is to avoid dead-end solutions. Use tools that can be adapted to new needs as they arise.

Cultures and the environments in which they function evolve together. People adapt to their environments while modifying them, where they can, to fit their needs. The human-computer interface is a special case because humans have created it for humans to be further changed by humans. Knowledge exchange is a special case of this special case because people who use virtual interfaces to learn are more likely to notice how the interface helps or hinders their learning. The interface, the culture, and the learning are tightly linked. This chapter describes those links and how an organization can smooth the adaptation of a knowledge-sharing culture to its online meeting place.

When Marshall McLuhan wrote "the medium is the message," he was exaggerating somewhat to make a point. The medium is certainly not the entire message, but it can be a major component of the total impression made by the message being transmitted.

The medium does, indeed, make a significant difference in communication. A stage performance of A Few Good Men does not impart the same experience as the movie version. Seeing a football game in person is qualitatively different from seeing it on television. And a conversation that takes place in a conference room does not leave the same impression as one that takes place through an online message board. The difference between any two media conveying the same content is experienced not only by the recipient but also by the sender. Compare, for example, standing up and speaking at a meeting with sending an email message to the same audience.

This medium-message effect applies just as powerfully to cultures as it does to individuals, which is important to keep in mind when selecting and designing the interface through which a community will converse. An online interface will force its users to alter their customary ways of communicating. Replacing face-to-face interaction with online interaction requires a period of adaptation during which individuals adjust their work habits and, in some sense, the way they project their personalities.

As individuals adjust to communicating online, their group culture also adapts. Most organizations and their cultures tend to resist change, so the end results of any change to social expectations must be justified. The key incentives to a group's going through adaptation to the online social environment are the need for effectively exchanging and generating knowledge and the faith that the new approach will deliver more knowledge faster and more efficiently than the face-to-face technique.

Another element that must be preserved in any transition to a new conversation environment is trust. If use of the interface erodes the participants' willingness to trust one another, which is a risk in any virtual communication, the credibility of the knowledge being exchanged will likewise be eroded.

Effective use of an online interface requires technical skills and social skills that are not emphasized in face-to-face conversation. Table 6.1 lists some of the differences in valued personal qualifications between the two meeting contexts. The differences may affect the membership, values, and productivity of the group. When a culture first goes online, part of the apparent medium-message is that certain members have suddenly become more visible, more active, more persuasive, and more competent than they ever have been in person. People with no prior experience conversing online find themselves lagging behind the veteran users in their ability to communicate clearly and convincingly or in the amount of their presence in the conversations.

An online discussion community is what we call a postocracy, where those who post their messages and opinions have more de facto influence than those who don't. A cultural hierarchy originally based on good in-person conversation and presentation skills may be turned on its head when taken online. People who have logged time on Web communities demonstrate their fluency in this new environmental language and assume the leadership roles in the digital conversations.

The more complex the new conversation environment, the greater this cultural disruption is likely to be. But even in the most basic online conversation environment (email), the change from standard office interaction is significant. Email affects the velocity of group communications. People expect immediate response to their email messages. They also feel increasingly overloaded by the volume of email they receive. Email, when used regularly, seems to try to force more communication into a day than is possible to deal with. At least in person, one is able to engage in only one conversation at a time. Email asks that we be engaged in dozens of exchanges simultaneously.

This hurry-up effect is even more pronounced when using the aptly named instant messaging tools, where real-time interaction is assumed and a failure to get an instant response from someone may be interpreted as a deliberate snub. People who structure their workday around checking email and keeping an instant messaging window open on their screen are more prompt in responding; thus, they are more visible—and probably more influential—in the online communities of which they are members.

Table 6.1. Comparison of Technical and Social Skills in Online Communication vs. Those in Face-to-Face Conversation

ONLINE SKILLS | |

|---|---|

Different: | |

Eye contact | Typing accuracy |

Tone of voice | Spelling |

Handshake | Formatting |

Posture | Description |

Timing | Responsiveness |

Facial feedback | Choice of words |

Similar: | |

Sense of agreement | Sense of agreement |

Manners | Manners |

Brevity | Brevity |

Eloquence | Eloquence |

Persuasiveness | Persuasiveness |

Insight | Insight |

Synthesis | Synthesis |

Originality | Originality |

Tact | Tact |

John Suler, a clinical psychologist who studies online group behaviors at Rider University in New Jersey, affirms that different genres of networked communication media enhance different aspects of our social experience. Being online and communicating with people who are online at the same time, he says, creates a sense of "presence" that conveys commitment to the group. Showing up regularly for a scheduled chat reinforces cohesion in the group. And he emphasizes that no matter how sophisticated the interface, there is no substitute for in-per-son encounters, which "help seal the relationship and make it seem more 'real'."[76]

The message conveyed as the by-product of any chosen medium must be considered in the context of its purpose and the culture it is meant to support. The tradeoffs of any virtual medium—for example, more convenience for less intimacy—must be taken into account. Rarely will the fit between technology and culture be perfect, and where it is not, the adjustments that will need to be made, either in the technology or the culture, should be acknowledged from the beginning.

The online world is an environment just as surely as are one's physical surroundings. It has different characteristics from the world of trees, sky, walls, windows, and air conditioning, but its features and rules are just as influential on the human activity that takes place within it. In the online world, software defines the virtual environment, and our human faculties interpret what we experience.

Some virtual places may "feel" like library stacks, others like auditoriums, and others like classrooms. The software, the site design, and the culture of the users are components of these electronic social environments. Many factors, including the following, help define the social experience when a group goes online:

Availability: how simple it is to access and navigate

Appearance: its colors, layout, design, and clarity of purpose

Complexity: the number of choices the user has to make

Synchronicity: the degree of immediacy in the communications

Richness: the amount of information contained in the communication

Population: the number of people who can and do use it

Depth: its number of layers of content and activity and their searchability

Rule structure: the policies in place for using the system

Interactivity: the extent to which users can affect its content

Privacy: the extent to which access is limited and secured

The results of a cultural assessment and knowledge audit—two evaluative approaches described in Chapter 5, "Fostering a Knowledge-Sharing Culture"— can identify traits that indicate how important these factors are to the people who use the interface. The artifacts of a culture—its symbols, language, and stories—can be represented, employed, and conveyed through the tools and design. The espoused values of the culture can be supported in the implementation of the technology and in the rules and policies put in place to regulate participation. Even cultural assumptions at the unconscious level will be reflected (and affected) as people adapt to working and communicating in the virtual environment.

In Chapter 5, we described the three main aspects of a cultural assessment: gap analysis, cultural alignment, and the fit of individuals to the organization. Here are some simple examples of how the interface might relate to each of these:

- Gap analysis.

Many gaps in knowledge-sharing values can be closed through the choice of appropriate software and design of the environment. If people are unaccustomed to logging on to a virtual meeting room to engage in conversation with colleagues, an interface that regularly delivers the latest conversational updates to them via email will engage them in a more convenient way and motivate them to gradually increase their participation.

- Cultural alignment.

Subcultures within the organization can become better aligned through the use of common interfaces and access to shared content. Each subculture may have its distinct conversation area, but some conversations may be shared between groups or across the entire organization so that differences can be aired and the useful cross-pollination of ideas can take place.

- Fit of individuals to the organization.

This can be improved as the culture goes online by hiring and training people for competence in the use of conversational interfaces. The introduction of new environments for conversation can, in effect, give a culture a fresh start by providing a new context for gathering and interacting where new histories of interaction and new relationships can be built.

Organizations often attempt to replicate established cultural practices when choosing their technologies, but this is not always the best idea. For example, many businesses that before 9/11 were accustomed to holding regular face-to-face meetings among people from geographically distant offices now save on travel time and expense by arranging virtual meetings using videoconferencing interfaces to provide a rich face-to-face experience. Instead of flying across the country, spending the night in a hotel, and sitting together around a conference table, the attendees assemble in special conference rooms in their home offices and converse with one another's video images.

Michael Schrage, of MIT's Media Lab, says such decisions respond to a "substitution imperative" and warns that in these cases simply "throwing bandwidth" at a problem to minimize change in social convention may not be the most effective solution.[77] Though it's cheaper than actual travel, it's still far more expensive than the lower bandwidth solutions of text communication, and the technique used in most cases does not address the real purpose of the meetings. Most video projections focus on the participants' faces yet surveys about the use of videoconferencing reveal that participants would prefer to see more of the information that the meeting is about.

Many management surveys through the years have shown that meetings, regardless of their format or environment, are considered by most workers to be the biggest wastes of company time. We've all spent too much time sitting in rooms and waiting for every person to finish talking about subjects that may or may not be relevant to the work we need to get done. Spending money on a video hookup to reproduce the same result seems to be not only inefficient but also unwise, except for the fact that it provides an opportunity for people to make brief (but virtual) eye contact with one another.

We recommend that rather than select technologies based on their ability to replicate in-person work practices, leadership should encourage the culture to adapt to technologies that bring maximum efficiency and effectiveness, even if they force some change in cultural habits. It is important to design the interface to serve established cultural traits and needs. However, it is equally important that the design exceeds what is possible in person and provides the culture with a meeting environment that can be customized to its new needs as they arise, which they most certainly will.

The best way to select software and design an interface for online collaboration is to get thoughtful input from the culture that will be using it, involving key members early in the process. Including actual users in the initial discussions of the knowledge network allows them to identify and prioritize their knowledge needs while describing their customary communications processes and the structure of their working groups, project teams, or communities of practice.

No one knows better what will work in an online environment than the people who are meant to use it for a purpose. As we've pointed out in previous chapters, the relationships of the user community to IT and to the interface designers are very important to the success of the technology. This involvement should begin early and should be maintained.

If a new interface needs to be designed, interviewing members of the user groups through use-case surveys should be part of the predesign process. Through these surveys, individuals describe the tools and capabilities they require and how they will use the interface in a variety of situations. Members' responses are analyzed by interface designers, Web masters, and IT professionals to compile a list of required features, assemble a blueprint for configuring the various software programs, and draw a map showing how various resources— such as the discussion space, information library, and member profiles—will be organized in the knowledge-sharing environment. As iterations of the design are built and made available for testing, the target group then serves as the guinea pigs, trying out the new design and providing input for tuning the interface.

The next stage of user involvement comes when the design is final enough to create training programs for its use. Input from future users at this stage identifies gaps in skills and experience that must be addressed through training. This is also the time to bring in representatives of other key areas of expertise within the organization, notably IT and Legal. Their involvement is essential to answer critical questions about security, technical feasibility, and policy considerations for the upcoming online interaction.

Early involvement of a community in the design of its future virtual meeting environment helps ensure that it will be used actively and effectively. The right features will be there, and the members will be prepared. But more important is the fact that such involvement motivates the community to make its project succeed. By helping to build the interface, members have a sense of ownership in it. That buy-in will carry forward as the group continues to innovate and customize its knowledge-sharing environment.

In the early days of computer networking, email was invented to answer the needs for sending and receiving messages. By 1980, groups were able to exchange similar messages and read them in the stored format of online conversations. These were the Usenet newsgroups. New and unique social conventions grew up around these interfaces because they were so simple and because people used only the most basic of the available commands. One could correctly say that a culture formed around the use of the Usenet interface. It was one of the first examples of the computer interface and the culture becoming intertwined.

Before the Web, people coming online for the first time had to adapt their activities to the limited available features rather than expect the interfaces to serve all of their interactive needs. The conferencing interface used at the WELL beginning in 1985 was only slightly more advanced than Usenet's. But the simplicity of a primitive interface is not necessarily a weakness. Simplicity is often the key to adoption of a technology because by presenting the user with fewer choices it requires less learning. Indeed, the people who lead the social use of any technology are more influential in the adoption of an interface than the features that are missing or included.

The WELL provided a simple tree-structured environment of conferences— grouped-by-topic, text-based collections of conversations, each administered by a so-called host. These hosts were entrusted with privileged access to technical tools that allowed them to manage the conduct and content of their conferences. They could freeze a conversation if they decided that everything that could be said had been said. They could remove a conversation from visibility if they thought it had served its purpose. And they could remove the contents of a posted message if it violated their local ground rules for participation. The capabilities of the software determined, in part, the social structure and ethics of the WELL culture. No host, for example, could remove a member's message without a notice appearing that the erasure had taken place. That feature guarded against a host surreptitiously censoring someone's message without any notice or explanation—a clear abuse of power in our freedom-of-speech culture.

Writer Thomas A. Stewart tells a story of how a consultant in the firm Price Waterhouse (before its 1998 merger with Coopers and Lybrand) joined with some colleagues to create a network where they could, in their words, "collaborate so as to be more innovative."[78] To that end, they set up an email list on Lotus Notes with "no rules, no moderator, and no agenda except the messages people send." Though the list was originally set up to serve a small group, it was open to any other employee. As of the writing date of the article, it had grown to 500 members and was considered the premier forum for knowledge sharing in the company. Lotus Notes has no advanced features for administering large email lists or for searching their contents. It's not an "ideal" platform in terms of design. Yet, the simple email list works because the right people use it, its use requires no training, and as the article points out, it's demand-driven.

The WELL's user community collaborated with its management in making improvements in the interface, but it was never the software that determined the culture. The social interaction and collaborative debugging of the conversational process made the WELL distinctive and attractive. There's no doubt that the PricewaterhouseCoopers group could benefit from some additional features for managing its growing volume of messages and participants. There is a place for appropriate technology if the users have a part in its selection and design.

The WELL had a slogan: "Tools, not rules." Wherever possible, the company would respond to customers' suggestions by creating a technical feature (or accepting an already created one from a technically adept customer) that would add to convenience or serve as a form of social mediation. Some of these tools allowed customers to configure their use of the WELL according to their social preferences. These tools also relieved management of some onerous and time-consuming responsibilities as social mediators and enforcers.

We tried hard to keep written rules to the absolute minimum, believing that fewer rules meant less inhibition and more creativity. In fact, our most effective methods for regulating the community turned out to be neither tools nor rules; they were setting good examples, selecting good hosts, and using public diplomacy. But personalization—the ability for the individual to tailor his or her online experience—can definitely eliminate some irritants from the use of an interface and can encourage people to participate more fully in online communities.

Tools that allow the user to personalize the online experience do eliminate the need for some rules. For example, most interactive group discussion interfaces now include a feature that allows individual users to filter the content presented to them. In some cases, they can choose to filter out messages posted by specific people. At the WELL, we called such a tool a bozo filter while other interfaces refer to it as the Ignore feature. In many interfaces, users can rate messages based on their helpfulness or quality and can choose to be shown only messages rated higher than a selected level. Still another filtering feature allows users to subscribe only to the conversations they want to be shown each time they visit.

These are all, in some sense, time-saving conveniences, but they also serve to improve the user's overall qualitative experience of the environment. If the quality of the perceived experience can be improved in terms of convenience, relevance, utility, and interpersonal compatibility, the user is more likely to be a regular participant. Such filters map to the social techniques people commonly employ for in-person interaction, where they selectively pay attention to some people (and some conversations) and ignore others. Some cultures may choose not to have filters because it's important to them that every member be exposed to everything and to everyone else.

As we'll describe in the next chapter, there are many different products available to support online conversation. Many different aspects of a culture may determine the features that are most appropriate and effective. These include the size of the population, the duration of its task, the kind of work that needs to be done, and the physical locations of its members. But the style and protocol of its interaction and conversation are the most important criteria for choosing the software that it will find most useful.

When computers and software were used only to crunch numbers, interface design was simply a matter of making input and output as simple as possible. Once networked computers became broad-based environments for communication and information sharing, their inadequacies for replicating in-person or even telephone interaction became obvious. The virtual social experience, though always advancing, will probably never be indistinguishable from physical presence.

Yet, as computers have improved at a rapid rate, the software that exploits their increased power and speed has brought us closer to providing options for reproducing the different ways we naturally communicate as humans. Not all of our conversations are the same. Some are one-on-one, others take place in a group, some are brief, and others are extended. Some are all business, and others are casual. So how do these translate to the capabilities of software? Consider the following choices, many of which overlap in their capabilities with each other.

In Chapter 7, we will provide some detailed descriptions of specific software programs and interfaces that support knowledge-sharing conversation. But in the context of their effect on social interaction and culture, we present the following descriptions of the main categories of those technical tools:

is, well, like mail: written correspondence, except it doesn't take days or weeks for an exchange to take place. It was the original online communications tool and is still the most widely used. One can send a message to an individual or a group that can be received almost instantly. A message can contain text, graphics, Web pages, animation, video, audio, or software. One can easily respond to any or all of the other recipients of a received message. Email client programs can be configured to filter and organize one's email to prioritize and keep track of numerous ongoing conversations. Email lists can serve as newsletters or as ongoing focused discussions. They can be moderated to reduce the noise-to-signal ratio, or their contents can be sent out in daily or weekly digests to reduce the clutter of individual messages.

- Discussion

is like meetings conducted through text. Discussion is our umbrella term for any asynchronous interface where multiple separate conversations can take place. Just as with email, the participants don't have to be using the system at the same time, but if they are, their exchange with each other can be almost instantaneous. Again, one can be involved in multiple conversations simultaneously, but in this case, all of the conversations are available in the same form to all of the participants, and those conversations—accessible through the same Web address—are easier to navigate than a collection of email folders.

Discussions can be open to all members of a community or privately accessible to only a few. Most discussion environments provide descriptive profiles of participants and tools for managing the contents of the discussion space. Old conversations can be retired and archived, and duplicate conversations can be merged. Completed conversations can be closed to new responses, and profiles can be searched at least by names.

- Chat

is conversation with time-based presence. Participating in a chat exchange is analogous to sticking one's head into a coworker's cubicle and asking a quick question or just making social contact. Chat (and instant messaging) happen in real time, unlike email and discussion where one can leave a message that might not be seen for hours or days.

In chat, there is a sensation of immediate engagement. Two people or a small group can carry on a very productive public or private conversation in a real-time environment. The conversation can be archived and reviewed, just as in email and discussion. But the immediacy of the interaction doesn't encourage deep thinking and the composition of long, careful responses, as do the asynchronous interfaces.

- P2P,

or peer-to-peer interfaces, are decentralized in that they are meant for communicating and sharing information between the personal computers of two or more correspondents without going through a hub or server. Instant messaging (IM) programs are similar to P2P programs because they connect individual peers using the same client software programs, but most IMs depend on central servers to coordinate communications.

True P2P programs directly connect client programs on individual personal computers to share documents, send and receive messages, and maintain shared schedules. They replicate the ad hoc arrangements that people make to collaborate as small groups on projects or interests without being slowed down by the central bureaucracy of the organization.

- Video

transmits the animated true-life faces and voices of participants. In its high bandwidth, most natural looking mode, videoconferencing is expensive. There's some question that, after the introductions, what people really want to see in such meetings is the faces rather than the information being exchanged. If the content of the meeting is better portrayed as numbers, charts, or Power Point slides, a phone call combined with some simple file transfers or email attachments will serve just as well for much lower expense.

- Document sharing

media are included in some groupware solutions that will be described in the next chapter. These may include coedited documents and virtual whiteboards or Web pages that can be worked on col-laboratively by remote team members. These usually augment voice or text conversations and may be included in the Event genre that follows. Software is also available that allows groups to follow a leader's tour through Web pages, a sort of "guided Web surfing."

- Event environments

seem to fit better into most organizations' needs and budgets these days with their increased restrictions on business travel. They permit the presence and immediacy of a true meeting format, including slide presentations, shared documents, and virtual whiteboards, while concentrating on synchronizing voice communications with those transmitted presentations. Chat conversation also can be coordinated with the information displays.

A powerful intranet can provide access to most or all of the foregoing communications options through specialized portals. Only P2P solutions stand alone, outside the context of the intranet. But each of these media, if used exclusively as the sole communications method for a knowledge community, will shape the format of the community in some way. Again, this can be beneficial; forcing change in communications practices often can bring out more of a group's communication potential. But if the wrong tools are chosen, or if adoption is rushed, the group may resist and become even less communicative as a result.

The challenge of matching interface with culture is simplified if there is a single, homogeneous culture in the organization. If communications methods and social networks are well established and stable, choosing the appropriate tools from the preceding list may not be so complex, especially given the flexible, multigenre nature of many products (which will be described in Chapter 7).

On the other hand, if an organization is large and diverse enough that distinct subcultures exist, each with different needs and habits, then the selection of tools and overall interface design must account for those differences. In the interest of economy and efficiency, the organization will want to avoid building completely different interfaces for each subculture but will still want to serve their differing styles of communication. If at all possible, a base or platform should be assembled that can be adapted, through custom formatting, to the unique needs and preferences of the various subcultures within the organization.

Building a replicable platform was the approach in designing for the initial customer community at Cisco Systems. The technical and business teams assembled tools and features—for conversation, content production, event calendars, and event presentations—at the portal level for the pilot project: the Networking Professionals Community. All of the components of that portal could be replicated to build other portals, and anyone in the company, regardless of their line of business, would be able to navigate to any specific knowledge portal on Cisco's intranet or extranet. There, they would find tools that were familiar though distinctive in their presentation.

Such an arrangement offers economies of scale in terms of software, engineering, design, and employee training because the one platform, with slight modification, can be used across all of the different internal or customer-facing communities. One training program can be adapted to serve all community staffs and stakeholders. A database and searching tool can gather and find knowledge that crosses business disciplines and departments. These original goals were realized in the creation of new knowledge-sharing community portals a year after the original community was launched. Yet there were important lessons learned in the design and implementation stages.

How a communications tool is formatted can significantly affect culture by restricting the way people are able to interact. Here is one common example with a long history where a discussion interface offers two different options for configuring conversation: linear and threading. Though they both support group interaction using text, these two very distinct structures determine the order, continuity, and responsive style of a conversation and can strongly influence the direction a conversation takes and who will participate in it.

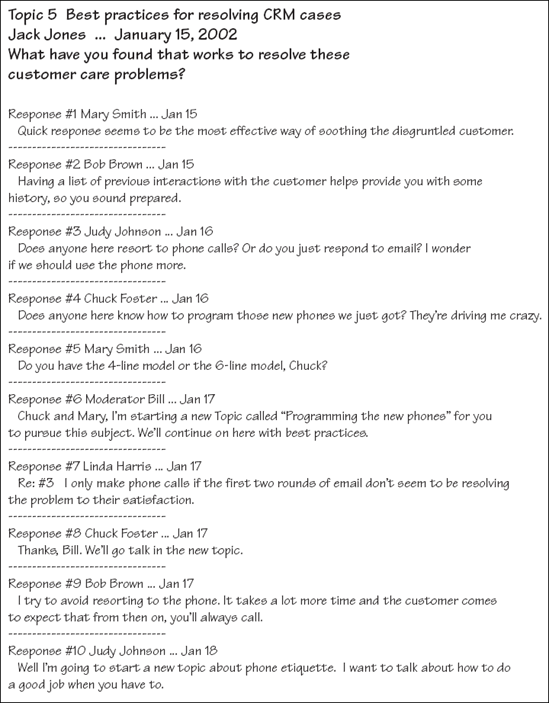

As Figure 6.1 illustrates, a conversation in a linear format is simply a series of responses following from the topic header, which serves as the title and introductory message for the ensuing conversation. The order of responses reflects the order in which people log on and post them. Sometimes the central topic of the conversation is interrupted (Response #3). This can lead to topic drift (Response #4) unless an attentive moderator (Response #6) brings the discussion back on topic by suggesting that the drift initiator start a new topic about his or her tangential interest. Using linear structure, this would be the most appropriate method for accommodating new linear topics.

A linear conversation is most useful when the reader can scroll up and down on the computer screen, navigating to different responses or conversational passages to get the context of the discussion. This is a more natural way of following a coherent conversation as opposed to the alternative approach of viewing only one response per screen. The best software gives the user the option of having the entire conversation displayed as one scrolling document or of breaking it up into page-sized chunks.

A similar conversation portrayed in a threading format is illustrated in Figure 6.2. Note the difference in terminology. The ability to respond directly, and separately, to a message (A) means that there is no need for a moderator to bring the discussion back on topic: Each thread becomes its own topic, which readers are free to follow or ignore as they wish. The main spine of the topic (B) continues on where participants respond directly to the header. But with no moderator present, a thread's subject may wander far from the original intent of the topic (C), confusing readers who depend on the topic header to inform them of its contents.

Figure 6.2. A threading conversation invites interruption and the branching off of threads from the main spine of the topic.

For coherence, each person who posts in a threading topic should first understand how to use messages as opposed to responses. If a user posts a message in response to another message, the conversational pattern breaks down and confusion results.

Note also that in threading software interfaces, there is often no scrolling display for conversations. Readers must click separately to open and read each message. Reading such a fragmented conversation is distracting, like listening to people talking over CB radio where every comment is followed by "Over" or "Back to you." For busy people, screen-by-screen participation in a conversation can seem laborious and inefficient.

Certainly not all groups are drawn to the long and extended conversations that are best supported by linear formats. When people are more interested in getting direct answers to specific questions—often provided by one experienced person rather than a group—the threading interface is considered easier to use and quicker to enter and exit. However, when people are more interested in posting their opinions rather than engaging in discussion, a threading format is more appropriate.

Regardless of the format, the members of an online conversational culture need to be considerate in the way they use their interface. Clarity, brevity, proper use of the conversational structure, and attention to staying on topic all make for more productive and effective communication.

Appropriate format is important, but the selection of appropriate tools should also consider the social characteristics of the groups that will use them. These aspects are especially relevant when the participants are new to meeting online, which is why some analysis of these cultural tendencies should take place before designing and formatting the platform for the group's virtual meeting place.

Through our years of working with online communities, we've developed a methodology for analysis that helps us to frame the interface needs of a conversational group. Such groups differ in ways that can be described along three overlapping dimensions, which describe their tendencies to converse, define common interests, and identify with each other.

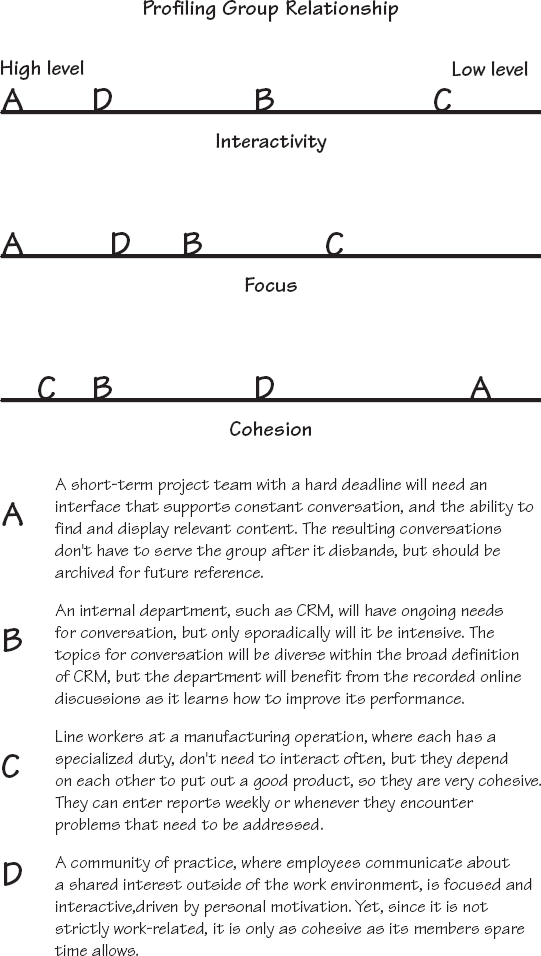

In the previous chapter, we described three different relationships between people and content. These ranged from groups that interacted without concern for other content to groups focused entirely on content of common interest. Between the two extremes were groups that interacted about shared content. Now we'll describe three dimensions along which groups can be distinguished from each other in terms of their style of collaboration. These dimensions help picture the balance of conversation and information that needs to be served in a group's ideal online environment. We refer to these dimensions as interactivity, focus, and cohesion, and each of them is considered along a continuum ranging from high to low.

Some groups thrive on interaction. It is required as part of their community definition. We described these groups in Chapter 5, "Fostering a Knowledge-Sharing Environment," and showed them yakking away with their small bubbles of focus floating about. Members of these groups are driven to check in often with their fellow conversationalists to discover and share the subtle tacit knowledge that they hold. Their purpose may be professional or social, but in either case, they exchange a lot of information and are constantly building trust and relationships as they converse. In a normal online session, they will spend 80 percent of their time in email, chat, or discussion rather than searching for information or viewing content.

Groups at the other end of the continuum couldn't care less about interaction. They are interested only in the information that will quickly answer their immediate questions, be it in documents, statistics, news, or graphic files. Members of these groups spend a minimal amount of time answering the obligatory email about the subjects that tie them together.

Most groups depend on a combination of interaction and content, with one complementing the other. They may converse intensively for a week, put together a research plan, then spend the next week assembling a library of documents and reading them. They may divide their online time constantly between interaction and content, or they may go through cycles of intense interaction and relative inactivity.

How a group naturally behaves along this continuum can define which genres and feature sets of the online interfaces will best serve its purposes. For a highly interactive community, feature-rich conversation tools are essential. For a barely interactive community, a good online publishing system and database combined with email may suffice.

The immediacy of the communication required also determines the kind of tools that are needed. Teams hard at work on a project may require secure instant messaging to share knowledge that can be put to use in the moment. Groups that are learning collaboratively without hard deadlines will be served well by message boards or email lists.

Where interactivity needs are high, a group may require a structured interface (for organizing and preserving their conversations) and tools for moderating conversation (to guide and facilitate efficient discussion). Hosts require software tools to fulfill their online social leadership activities.

The technical interface, in communities of high interactivity, must also provide searchable, descriptive member profiles to inform people of each other's skills, backgrounds, and interests. In a social network, such personal context is just as important as the information that fills the core of the group's common interest. In a knowledge network, all participants will have a credibility factor associated with the experience and know-how they bring to the conversation.

A community's tendencies toward interactivity and conversation may evolve, of course, once they have access to the means for conducting online conversation. For a group that is geographically scattered, shared access to a message board may be its first opportunity to initiate discussion and continue communicating day after day. The online discussion space may provide the first chance for natural group leadership to emerge and motivate wider participation in the dialogue. That leadership can be at least as important as the interface in stimulating interaction, but poor interface design can frustrate attempts to conduct effective discussion.

Communities naturally come together around common interests. For some, those interests are vital and concentrated, but for others, they are more casual and diffuse. Most of us identify with many different communities, with our focus ranging from intense involvement (raising kids, immediate health concerns, a current job) to amused curiosity (the football rankings, lawn care techniques, Hollywood gossip).

A highly focused knowledge community, such as a project team with a hard deadline, will have agreed-upon goals, acknowledged experts, concentrated information needs, and aligned motivation. In an office setting, these people would talk to each other frequently, hold a standing reservation on a conference room, schedule regular meetings, map out and follow a work process, and set mileposts for establishing their progress.

Focused communities are the best populations for leading online pilot projects because their inherent motivation to solve common problems helps them clearly recognize and agree on their communication needs. Their members participate with enthusiasm and are aware of how the interface slows them down or inhibits their collaboration. They help debug initial attempts at platform design so that subsequent communities, which may not be so unified and focused, will have a smoother time using their versions of the platform.

Groups with no common focus don't really qualify as groups at all. But a realistic other end of the focus continuum would be people in the organization who primarily work on their own but share interest in company news and resources provided through the intranet. Their interface needs are no more special than any other member of the organization.

In the context of serving high focus through online interfaces, the main differences between groups are in how much of their time is spent in the online environment pursuing their focused activities. Those activities probably include lots of conversation and access to common libraries of information. Access to their online area may be restricted to maintain high levels of expertise and continuity.

High focus also adds to the list of requirements a higher level of expert leadership. Knowledge sharing and learning usually put a group's focus into the higher range because of the specificity and immediacy of the knowledge being sought. But focus, as we all know, is difficult to maintain.

The longer a focused community remains intact, the less focused it may become. It won't look that way from the outside, but within even the most narrowly focused group, the diversification process is at work. A project to design a single product soon breaks into many subprojects for organizing the many pieces of design and production. A team brought together to plan an event is soon involved in many different conversations about the various aspects of planning, security, lighting, sound, parking, publicity, and so forth.

A population with little in common, provided with the ability to meet and converse, will tend to organize and form many different communities of focus. Most public community sites on the Web began by attracting random Web surfers and evolved into collections of small online neighborhoods formed around a wide variety of subjects: people from California, libertarians, NASCAR fans, singles looking for dates, people with diabetes, and so on.

The previous two paragraphs illustrate that group focus at either end of the continuum seems not to be a stable situation. In our experience, the focus of most groups tends to oscillate around a middle point, being more intense at times about some subjects and less intense at other times about different subjects. This leads us to believe that the tools for serving knowledge communities should be able to support a wide range and that designing for the high-focus needs is the best practice for most groups.

Very loyal groups—those with a high level of internal identification, commitment, and significant history—behave differently from those that have only recently come together or that recognize few common interests. Cohesion is different from focus in that it is based more on trust, whereas focus is based more on topic. The interpersonal relationships in cohesive groups are strong. They can endure difficulties, even inadequate interfaces and the technical problems that periodically prevent members from connecting.

Cohesion doesn't drive communities to learn or meet deadlines. High cohesion builds familiarity and shared knowledge over time. Cohesive groups understand which members know what and have established practices for interaction and collaboration. They may have formed before they had access to an online meeting space, but their social ties are solid and serve as incentives to bring all members into whatever meeting environment is agreed upon.

Less cohesive communities might fall apart because of such problems as interface difficulties, internal disagreements, miscommunication, absence of strong leadership, and the occasional breakdown in group connectivity. They require much more technical reliability and better custom interface design to keep them together.

The three dimensions for evaluating a group's collaborative tendencies are closely related. We can imagine groups that are very interactive, very focused, and very cohesive, yet few actual communities fit that description all of the time. Most groups that can benefit by conversational knowledge exchange are high in only one or two dimensions and then only some of the time. A highly interactive community may not be very focused. A newly formed community won't have much cohesion, though it may be very interactive. A community with intense focus may not feel compelled to interact at all, preferring to have common access to content that is kept current and detailed.

In Figure 6.3, we show four examples of communities with different profiles along the three continuums of interactivity, focus, and cohesion. Each profile describes different interface needs.

Profile A, a short-term project team, calls for an interface that all members can access and use quickly, with minimum need for training or technical integration. With no group history and a short group lifetime, simplicity of use is the most important factor. Email may be sufficient if there is no need for organizing numerous parallel conversations. A basic message board with access limited to team members would permit some helpful organization of project-related discussions. A content publishing component would permit team members to post documents and to share project management timelines.

Profile B, a stable department within an organization, needs an online meeting place for certain administrative conversations and content but is driven more by routine than deadlines. It has the time to learn how to use and manage its space on the intranet. It can benefit by preserving certain conversations as a record of interaction. A basic message board that can send out the latest postings in email will serve to involve employees who don't voluntarily log on to the site. Such staffers receive digests of online conversations on a regular basis, inviting them to participate but not forcing them to spend much of their time in the virtual meeting environment. The environment serves as a gathering place for shared knowledge and a conversation space for sharing knowledge when it is required.

Profile C is a group of workers who lack the time to get online regularly but who hold valuable knowledge about their hands-on skills and experience. Regular daily or weekly reports or involvement in periodic online debriefings may serve as the means to harvest their knowledge and allow them to tap into the knowledge of other resources in the company. Because they spend so little time online, their interface to the Net should be as simple and quick to use as possible. Online surveys and email might be the most appropriate way to gain their participation.

Figure 6.3. Four group profiles and the implications for their most appropriate interface design features.

Profile D is an ongoing, focused population that interacts for enjoyment. The knowledge generated in their conversations may or may not be of direct value to the company, but their relationships do offer the potential of releasing valuable knowledge and experience indirectly available to the company. Communities of practice are cohesive as long as their members work for the organization and have time to participate, but their motivations are powerful for making the best use of whatever tools are available for group communication. As we'll describe in Chapters 7 and 8, communities of practice differ greatly in their needs for technology. Their motivating focus makes them more adaptive than communities that are formed more artificially to accomplish work-related tasks.

Initial group tendencies, as we've pointed out, are not deterministic; they are likely to change and fluctuate. But as a group takes its first steps into the online meeting space, it's worthwhile to address these natural tendencies for collaboration with the intention of making its early experience as nondisruptive as possible. Forcing cultural change by trying to fit square-peg cultures into round-hole interfaces has a low probability of success. But once accustomed to working through an online interface, the square pegs can change their shape and adapt to interfaces that they find more helpful to their reaching goals.

Besides the software that enables conversation and content publishing, there are two other key elements that can make or break an online knowledge-sharing network. One has to do with the people who are considered members of the network, and the other has to do with the rules that apply to use of the network. Both must be available through the interface if effective communication is going to take place.

Most intranets provide space for their users to describe themselves to varying degrees of depth and detail. Some companies provide only name, title, and contact information, but others permit users to post more elaborate descriptions including personal histories, information about hobbies and family, and even entire Web-based home pages.

In a knowledge-sharing community, it's important to know with whom you're communicating, and to be able to find people with whom you need to communicate. Such professional and experiential information is often posted in what are called yellow pages directories, searchable from within the intranet or specific portal used by the community. Many discussion software programs also provide fields to be filled in by each registered user that can be accessed by other users from within the interface. Ideally, though, the profile page should be customized to the needs of the specific knowledge community, with access to some field restricted to that community.

Detailed personal profiles, even with photos and other graphics, can fill the same need for rich content that some believe can be obtained only through in-person presence or high-bandwidth videoconferencing. Appropriate profile design can elicit well-rounded descriptions of community members that engender trust—the gold standard in knowledge exchange.

A knowledge-sharing community's culture combined with the features of its online interface describe most of its style and process, but policies and guidelines clarify its boundaries, manners, and ideal behaviors. Just as appropriate tools and interfaces are important to implement on the technical side, appropriate use is important to define on the social side.

Policies generally align with an organization's internal values and legal limitations. Examples of policies relevant to online conversation are to not share company secrets with outsiders and to be courteous with customers contacted through the Net. There may also be policies describing who in the company has access to which portals and information directories.

And by now, every company should have a very visible and comprehensible privacy policy on both its internal and public-facing Web sites. Where the population has any questions about personal privacy in an online community, a policy should be spelled out for that purpose. Information entered in one's professional profile should not, for example, be distributed publicly without the owner's consent.

In some companies and situations, people with ideas, suggestions, or complaints to offer for the benefit of the company are reluctant to post them online under their true names. A company must decide whether or not to allow anonymous participation in online exchange or how such anonymous contributions can be made. Of course, the ideal is to have sufficient trust in the organization that fear of reprisal is not a factor, but few organizations of any size engender such openness.

Policies regarding entitlement—who has access to what portal or conversation space—can have a great effect on culture. Restricting access to conversations can keep them more focused, increase trust, build cohesion, and make them both more effective and more efficient. But restricting access also can block valuable complementary or critical voices from being heard or prevent the cross-fertilization of useful ideas from diverse viewpoints and other communities.

Guidelines, as distinguished from policies, are more proscriptive, suggesting interactive habits that are supportive of interaction and would be good for community members to develop. One useful guideline for posting messages in almost any online conversation is to divide messages into small paragraphs for easier reading. Another reliable guideline is to keep messages as short and concise as possible. And of course, welcoming newcomers to an online meeting place is not only good manners, but it leads to greater overall trust and participation.

An online community's policies and guidelines should provide a pretty accurate reflection of its culture. Guidelines may differ among an organization's subcultures. Policies generally come from the top level of the organization, though a cohesive community of practice may have its own policies for membership or submission of new content. In the interest of preventing too much irrelevant conversation, a focused knowledge community might also have its own policies limiting the range of topics that can be addressed in its online forum.

It's often through guidelines, which gradually grow into a compendium of good practices discovered in actual interaction, that online cultures become established and evolve. Guidelines, in some sense, reflect the folk history of the community and incorporate its distinct jargon. Guidelines should be open to expansion and modification by the members of the community and should be made prominently available to prospective and new members as they join.

So far, we've been looking at culture almost exclusively in the context of internal communities and knowledge-sharing activities. But increasingly, organizations are communicating with external communities for a variety of reasons. Carrying on knowledge-sharing and knowledge-seeking conversations with customers, vendors, partners, and consultants requires a cultural interface between that of the organization and that of the group on the other end of the communication.

Companies increasingly use the Web to learn about the people they do business with. Marketplaces are increasingly showing themselves to be conversations. The terms of those conversations are increasingly escaping control by the company, even when it provides the conversational interface. The customer is often more seasoned in use of the Web than the company providing the service. The customer is in the driver's seat.

The implications of these truths to this chapter are that the company must learn to be as sophisticated in its use of interactive technologies as the people it is trying to serve. Instant messaging may not be the most compatible communications format for an organization's culture to use internally, but it may be the necessary format for responding to requests for support from customers pushing its online shopping carts through a confusing Web-based catalogue. An online discussion community provided for users of the company's products cannot become a forum for argument about the company's sales return policies. The company's presence in the public forum of the Internet marketplace must be as a member of this new relationship, this new culture where the common interest is high-quality product and service. We'll focus on some best practices in knowledge sharing with external communities in Chapter 9, "Conversing with External Stakeholders."

There is an undeniable link between the elements of a culture and the environment in which the culture exists. When the environment is Cyberspace, that link is even more significant because the technical world lends itself to relatively simple customization. Communication in a virtual space requires new skills and rewards different aptitudes from those that work in the face-to-face world. And each different medium and format for conversation in the virtual world adds its own distinct context to the communication that takes place through it. For those reasons, it's important to understand those contexts and to understand the elements of a group's culture before choosing and designing its online meeting place. Simplicity of design and minimal disruption in routine communications methods are often more effective for encouraging knowledge exchange than elaborate software solutions.

Cultural assessment and knowledge auditing help match groups to compatible technical features as a culture takes its interaction online. Evaluating a group's propensities for interaction, focus, and cohesion is important in selecting appropriate software and designing the knowledge exchange space. Software and portal designs have identifiable strengths and weaknesses that can make the transition from in-person to virtual communication smoother or, if choices are made carelessly, disastrous. It pays to design the virtual destination right the first time because bad experiences become disincentives for making second efforts.

Well-designed online environments are malleable and likely to be changed once a culture begins using them. The environment affects the culture just as the culture should be able to affect its environment. An organization must decide, as it begins building a virtual space for knowledge sharing, whether that space is dedicated to only one of its subcultures or is meant to serve as a template for use by others of its subcultures. Tools that can be formatted to meet diverse needs and cultural habits provide the economy and flexibility that allow the organization and each distinct subculture to customize them and adapt them to fit different purposes and styles of communication.

It's important to remember that a culture's tendencies can and will change with time, after the transition to the virtual meeting space. Carry QueRY to pages]Initial design for that space should not be set in stone but should be compatible enough with the group's current habits to motivate its members to use it with as smooth a transition as possible. Appropriate policies and guidelines will further smooth the transition.

Where the virtual meeting space is to be shared between internal and external cultures, design needs of the external groups should have top priority. They are, after all, the guests in the conversation. Only if they are satisfied enough to participate can the company learn what it needs to know from them.